Abstract

This paper highlights the challenges of performance management in health care, wherein multiple different objectives have to be pursued. The literature suggests starting with quality performance, following the sand cone theory, but considering a multidimensional concept of health care quality. Moreover, new managerial approaches coming from an industrial context and adapted to health care, such as lean management and risk management, can contribute to improving quality performance. Therefore, the opportunity to analyze them arises from studying their overlaps and links in order to identify possible synergies and to investigate the opportunity to develop an integrated methodology enabling improved performance.

Keywords: health care, lean management, clinical risk management, quality, health care processes

Introduction

The pressure to “review spending” as a result of reduced public resources is affecting public health care costs, which have to be reduced by eliminating waste1 while considering the level of quality at the same time. In addition to considering patients’ increasing awareness of health care and the growth of organizations in defense of patients, standards of quality must be guaranteed for the accreditation process, which can follow four different models, ie, “visitatie”, International Organization for Standardization, European Foundation for Quality Management, and organizational accreditation, or the Joint Commission International program, which combines the strengths of all of these models into a common health care quality evaluation.2 Moreover, achievement of a high level of quality in health care is pressed for by national and international organizations,3–5 as well as by ethical and social concerns. All the aspects mentioned above complicate the health care system, which indeed is complex in itself. As a service business, it is characterized by intangibility, heterogeneity, and inseparability of production and consumption.6 These critical elements of any service company affect the degree of process standardization, marketing and communication polices, employees’ roles, management capacity, and mechanisms of quality control and performance evaluation.7 In addition to having these special features, health care companies also provide a unique and critical service, considering the particular condition (both physical and psychologic) of their customers.8

Shortell and Kaluzny9 have individualized other peculiarities of health care companies:

high variability and complexity of the work, given that the nature of a substantial part of it is considered urgent and must not be delayed; the work involves a high degree of specialization and has a limited tolerance of error

work activities are highly interdependent, requiring a high level of coordination between different professional groups

people, who play a relevant role in the organization, are highly professional and loyal to their professional category rather than to the organization they work for

there is little organizational or managerial control on medical staff, which strongly influences the effectiveness and efficiency of health care service.

The central element around which all the activity carried out by the health care organization revolves is the human relationships developed between the patient and health care staff. Therefore, the centrality of people (and not the exchange operation, as traditionally occurs in economic studies) is what best represents the distinctiveness of these companies.10 According to Serpelloni and Simeoni,11 the general objective of a health care organization is to protect and promote citizens’ health with the highest technical quality and providing customer satisfaction at the lowest cost.

This paper discusses how it is possible to pursue these different performance objectives, considering different points of view and highlighting the potential of new approaches that could enable health care organizations to successfully manage their performance, especially if adopted in a synergistic way. The paper is organized as follows: management of performance in health care is presented considering different theories in the second section; recent managerial approaches supporting performance management are discussed in the third section; and opportunities for future research emerging from the previous discussion are developed in the final section.

Management of performance in health care

The issue of pursuing different performance objectives, as developed from the definition of Serpelloni and Simeoni11 in the health care context, is not new; Skinners12 and Hayes and Wheelwright13 highlighted the need to choose the performance objective on which to focus at the expense of others. This approach has been discussed in the literature by several authors, who have underlined its limitations but also noted its potential, comparing it with the so-called “cumulative” models and with the theory of performance frontiers and performance improvement.14–20

In particular, many of these theories try to provide a sequence for pursuing different performance objectives. Perhaps the most famous of these is the theory of the sand cone of industrial origin,21 which recognizes quality as the primary target on which to focus before developing strategies aimed at improving flexibility and delivery, obtaining finally, as a causal effect, a reduction in costs. This means that there is an optimal sequence for achieving improvement in performance, following a cumulative process. In order to obtain stable improvement, first a minimum level of quality should be reached; only afterwards can the firm consider aspects of reliability. To increase the levels of quality and reliability, the next step is to improve the speed of internal processes; the flexibility of the response will be the most effective way to do this, coherently changing the organizational structure. Only after achieving a minimum level for this performance should firms consider efficiency.

The authors suggest that, by focusing on quality first, organizational abilities are nurtured more, thereby emphasizing cost efficiency objectives. Most companies that have developed quality improvement programs also report lower costs. Takala et al22 observed that all the layers of the cone are supported by the quality of the processes; cost efficiency is at the top of the cone as the ultimate goal, with only a small influence on the structural stability of the cone itself. In the study reported by Takala et al,22 the sand cone is adapted with the aim of highlighting the successful strategies that an airline company has to pursue to succeed; flight safety is placed among the basic pillars, along with high quality of personnel, know-how, and work environment and technology.

Turning to the health care context, quality plays a fundamental role, as argued before, and patient safety could constitute one of the basic pillars. Therefore, the definition of quality in health care seems to be a critical issue. Although the theory of the sand cone should be adapted to the context21 and to the strategies identified, quality seems to be the starting point according to many studies.14,15 Therefore, quality in health care needs to be defined. Because health care is a service industry, we could refer to the literature, in which quality of service has been defined as a measure of the match between quality of performance and customer expectations.6,23

The distinction between customer satisfaction and quality of service has been studied by several authors, leading to the definition of Bitner and Hubbert:24 “the consumer’s overall impression of the relative inferiority/superiority of the organization and its services.” Some studies have translated these concepts into health care, despite difficulties of implementation,25,26 where some authors describe quality as the extent to which the desired health outcomes or “expectations” of patient services are met.27,28 However, considering that the right to health care is universally recognized and protected,29,30 quality in health care should go beyond patient expectations and satisfaction. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,31 quality is doing the right thing, at the right time, in the right way, for the right person, and achieving the best possible results. In line with Buttell et al,32 quality of care should increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes, being consistent with current professional knowledge (professional practitioner skill) and matching the expectations of health care users (marketplace).

Adopting a meaning of quality of service that Holbrook and Corfman33 would define as more mechanistic (involving an objective aspect or feature of a thing or event) than humanistic (involving the subjective response of people to objects and therefore a highly relativistic perspective), quality should also take account of other aspects, such as patient safety and error reduction. These latter issues should be considered a subset of a larger, more complex, and multidimensional concept of quality of care.

Considering the definition used by the World Health Organization,34 a health system should be considered as being of a high level if it is effective, efficient, accessible, acceptable, patient-centered, equitable, and safe. These are the same characteristics recognized by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality35 and reported by the Institute of Medicine36 for health care service of high quality, ie, safe, timely, patient-centered, efficient, effective, and equitable.

To meet this definition, it is essential to pursue objectives of improving quality, reducing medical errors, and decreasing costs by eliminating all forms of waste, based on the four areas into which quality can be split, ie, technical quality, efficiency, risk management, and patient satisfaction.37 However, these aspects should be adapted to a process-based perspective (eg, considering process efficiency instead of efficiency in use of resources). Therefore, based on the definition of quality used by the World Health Organization34 and shared by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and Institute of Medicine,35,36 which seems the most comprehensive so far, adequate managerial methodologies should be developed in health care to achieve effectiveness, efficiency, patient-centered organization, and safety at the same time.

Recent developments in managerial approaches to improve performance

Managerial approaches derived from the industrial context, such as health care lean management (HLM) and clinical risk management (CRM), could help to ensure the quality attributes mentioned above, but a single approach may not be sufficient to guarantee them all. Following the definition used by Walshe and Dineen,38 CRM is: “… an approach to improve quality in health care which places special emphasis on identifying circumstances which put patients at risk of harm, and then acting to prevent or control those risks. The aim is to both improve safety and quality of care for patients and to reduce the costs of such risks for healthcare providers.” Therefore, it seems that inadequate management of quality and patient safety leads to an increase in costs. The need to adopt CRM is also born from the crisis that happened in the insurance market, resulting in substantial increases in insurance premiums, which forced the need to adopt different techniques to manage clinical risk.39

Clinical risk, defined as the “dark side of quality”,40 therefore has an impact on the level of costs if not properly managed. To achieve this error reduction, ie, ensure greater patient safety, several basic CRM tools have been used,41–47 ie, risk identification, risk evaluation, risk treatment, and risk monitoring.48,49

Following the logic proposed by Ferdows and De Meyer,21 quality and patient safety have to form the base of the sand cone in health care, ie, they have to be guaranteed first, consequently avoiding a negative impact on efficiency performance.

Stuart50 highlighted, as did Taguchi, the definition of quality loss function in the industrial sector. Non-quality costs included were repairs, assistance service, waste, and warranty; moreover, Stuart verified that the amount of losses is proportional to the square of performance deviation from the target. Cosmin and Stanciuc51 also considered the costs supported to ensure high levels of quality in the previous relationship. It can be expected that even in health care these relationships could be verified, given the parallel that is barely visible in at least some types of costs (eg, waste and assistance), in the costs of bad quality, and those related to preventive health care, highlighted in several studies.52,53 In CRM, prevention activities with double-checks and duplications are often carried out, even if they are not always necessary.

In the health sector, industrial instruments and techniques of quality management have being adopted for quality improvement, as reported in the academic and management literature over the last 20 years. Among them are PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, Act), quality function deployment, International Organization for Standardization 9000, total quality management, business process re-engineering, Lean Six Sigma, quality control, quality assurance, quality function deployment, and lean thinking.54–61 In recent years, the use of tools for lean management, for example, has been increasing, inspired by the “Henry Ford production system.”62–64

Despite implementation of these different practices, errors reported in health care are still unacceptable and related costs still show a positive trend, as shown by data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.65

Starting from the definitions provided, overlaps and possible integration between the approaches of CRM and HLM emerge, connecting the concepts of added value and perfection present in lean principles (ie, precisely specify value, identify the value stream, make value flow without interruptions, pull approach, pursue perfection),66 to the definition of quality used and required at the international level (World Health Organization). On the other side, CRM, through the tools and practices it provides, allows pursuit of perfection, error reduction, and greater efficiency.

Therefore, there is a two-way arrow connecting CRM and HLM: not only is quality the necessary basis for ensuring cost reduction, but HLM, as a business management strategy encompassing a set of principles, practices, and methods for designing, analyzing, and managing processes,55 could support the detection of high-risk situations. In fact, considering Reason67 and Kohn et al,68 reliable systems can develop only if the culture of blame is abandoned and the right barriers, in terms of procedures, protocols, and process control, are erected.

HLM supporting CRM is further confirmed by the following definition of HLM.66,69 HLM is a managerial approach to identify and eliminate waste, while improving flow of activities to maximize customer value; it considers specification and standardization of work processes, organization of work in such a way that unexpected events are easy to spot, and deployment of activities that find and fix mistakes.

A recent literature review70 analyzed the links and overlaps between CRM and HLM. From this study, it emerged that the two approaches are implemented separately and alternatively, without following an integrated view. Moreover, the authors identified that there are no studies focusing on the relationship between HLM and CRM. Notwithstanding this, in HLM papers, some partial objectives of CRM are pursued and some CRM methodologies are adopted, but not all the phases of the CRM process are considered.

Some empirical cases have achieved quality improvement and patient satisfaction, reducing waste and cutting costs.71,72 However, other studies have shown that the measures of quality in health care are not appropriate, and little attention is devoted to other aspects, such as the impact of such approaches on employees,64,73 while the advantages in terms of cost and efficiency improvement are evident.64,74,75

Some indications emerge from the cases examined; in particular, this approach should be adopted after providing the right education and training to both employees and management, given that if a real commitment from top management is lacking, it is unlikely that implementation of these practices will be successful. In addition, this approach should introduce a shared culture across the entire organization; it should not be adopted in some selected hospital units, because this may lead to creation of islands of excellence and achievement of local targets only. Successful implementation requires a detailed vision of the process, which involves different departments and different areas, depending on the health care process concerned.

Opportunities for future research

Two future research streams emerge from the previous considerations, the first of which concerns quality approaches and the measurement system. The following aspects should be investigated in more detail:

quality of care should be defined in an unambiguous and shared way, considering the different points of view discussed above, and the characteristics defining quality should be usable both in adopting a system view or referring to the processes view

research should be conducted to define quality measures allowing to evaluate and control the achievement of high quality

replication and adaptation of the sand cone theory could be studied, identifying the strategies that contribute to obtaining high quality levels

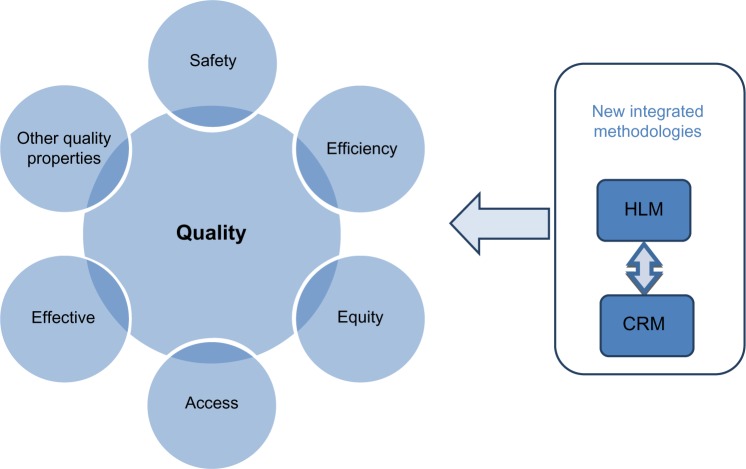

new managerial tools and practices, drawn in particular from HLM and CRM, should be adopted to measure, control, and improve quality in each of the components (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Quality definition and impacts of new managerial approaches on quality performance.

Abbreviations: HLM, health care lean management; CRM, clinical risk management.

Considering the multiplicity of objectives, a second research stream concerns the opportunity to develop methodologies that integrate different managerial approaches in order to gain advantages from each of them. In particular, future research could focus on the development of an integrated methodology to manage clinical processes, exploiting the synergies between HLM and CRM. This stream entails the following:

comparing lean management project phases with the CRM process to analyze the overlaps and links between them

investigating comparatively the main managerial tools, practices, and guidelines adopted in HLM and CRM

identifying projects with both HLM and CRM evidence as “safety and lean projects”; theoretical and empirical research should be undertaken in order to provide guidelines to succeed in the implementation of these projects; the possibility to build a synergic process to manage “safety and lean projects” has never been considered in the literature

the hypothesized new integrated managerial approach will probably need new professionals, sometimes called “T-men,”76 who are able to integrate knowledge, management systems, and people; this appears to be confirmed by the presence of personnel with engineering and management capabilities in the first lean management projects with safety fallout.

Regarding the key factors for successful implementation of “lean and safety projects”, first indications could be grasped from studies in the two different research streams. In the industrial sector, Shah and Ward77,78 have highlighted the need to consider “soft” aspects in addition to the “hard” ones. Lean production is defined by Shah and Ward77 as an integrated sociotechnical system that should not neglect the social dimension during its implementation. Given that lean is a philosophy, guidelines should be followed to create a lean culture.79–81

Many of the guidelines recommended for successful implementation of lean management projects are not so far from the ones highlighted by authors studying CRM.48,82 Moreover, Cagliano et al83 give an example of early incomplete research that tried to combine some aspects of CRM with lean techniques.

The chance to develop these new research streams thus seems reasonable and reveals interesting opportunities to extend current knowledge in the academic health care literature. Further developments will contribute to finding successful solutions to overcoming health care challenges, achieving the multiple objectives of health care companies and evolving through a better society.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Stuckler D, Basu S, McKee M, Suhrcke M. Responding to the economic crisis: a primer for public health professionals. J Public Health (Oxf) 2010;32:298–306. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donahue KT, Vanostenberg P. Joint Commission International accreditation: relationship to four models of evaluation. Int J Qual Health Care. 2000;12:243–246. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/12.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization The Ljubljana Charter on Reforming Health Care Ljubljana, Slovenia: European Member States; 1996Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/policy-documents/the-ljubljana-charter-on-reforming-health-care,-1996Accessed October 14, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Regional office for Europe. HEALTH 21 – health for all in the 21st century Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/policy-documents/health21-health-for-all-in-the-21st-centuryAccessed October 14, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health, Department of Programming Quality and National Health Service: References and Documentation. 1999.

- 6.Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J Mark. 1985;49:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bateson JE, Hoffman KD. Managing Service Marketing. New York, NY: The Dryden Press, Harcourt Brace College Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cicchetti A. L’Organizzazione dell’Ospedale [The Hospital Organization.] Milan, Italy: Vita e Pensiero; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shortell SM, Kaluzny AD. Health Care Management: Organization, Design, and behavior. New York, NY: Delmar; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruzzi S. La Gestione dell’azienda Sanitaria: Innovazione e Scelte Strategiche per un Nuovo Scenario Competitivo [The Management of Health care Organization: Innovation and Strategic Choices for a New Competitive Scenario.] Milan, Italy: Giuffrè Editore; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serpelloni G, Simeoni E. Quality Management. Verona, Italy: La Grafica; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skinner W. Manufacturing: The Formidable Competitive Weapon. New York, NY: John Wiley; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes RH, Wheelwright SC. Restoring Our Competitive Edge: Competing Through Manufacturing. New York, NY: John Wiley; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noble MA. Manufacturing strategy: testing the cumulative model in a multiple country context. Decision Sciences. 1995;26:693–721. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lapré MA, Scudder GD. Performance improvement paths in the US airline industry: linking trade-offs to asset frontiers. Production and Operations Management. 2004;13:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmenner RW, Swink ML. On theory in operations management. Journal of Operations Management. 1998;17:97–113. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Da Silveira G, Slack N. Exploring the trade-off concept. International Journal of Operations and Production Management. 2001;21:949–964. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mapes J, New C, Szwejczewski M. Performance trade-offs in manufacturing plants. International Journal of Operations and Production Management. 1997;17:1020–1033. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayes RH, Pisano GP. Manufacturing strategy: at the intersection of two paradigm shifts. Production and Operations Management. 1996;5:25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyer KK, Lewis MW. Competitive priorities: investigating the need for trade-offs in operations strategy. Production and Operations Management. 2002;11:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferdows K, De Meyer A. Lasting improvements in manufacturing performance: in search of a new theory. Journal of Operations Management. 1990;9:168–184. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takala J, Leskinen J, Sivusuo H, Hirvelä J, Kekäle T. The sand cone model: illustrating multi-focused strategies. Management Decision. 2006;44:335–345. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis RC, Booms BH. The marketing aspects of service quality. In: Berry L, Shostack L, Upah G, editors. Emerging Perspectives on Services Marketing. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bitner MJ, Hubbert AR. Encounter satisfaction versus overall satisfaction versus quality: the customer’s voice. In: Oliver RT, Rust RL, editors. Service Quality: New Directions in Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor SA, Cronin JJ. Modeling patient satisfaction and service quality. J Health Care Mark. 1994;14:34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andaleeb SS. Service quality perceptions and patient satisfaction: a study of hospitals in a developing country. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:1359–1370. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laffel G, Blumenthal D. The case for using industrial quality management science in health care organizations. JAMA. 1989;262:2869–2873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohr KN, Donaldson MS, Harris-Wehling J. Medicare: a strategy for quality assurance. V. Quality of care in a changing health care environment. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1992;18:120–126. doi: 10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30518-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Active Citizenship Network . European Charter of Patients’ Rights. Brussels, Belgium: Active Citizenship Network; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.General Assembly Resolution Universal declaration of human rights. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly, 10.12.1948 Available from: http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/history.shtmlAccessed October 14, 2013

- 31.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Testimony on Health Care Quality 2013Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/news/newsroom/speech/index.htmlAccessed October 14, 2013

- 32.Buttell P, Hendler R, Daley J. Quality in Healthcare: Concepts and Practice. The Business of Healthcare. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holbrook MB, Corfman KP. Quality and value in the consumption experience: Phaldrus rides again. In: Jacoby J, Olson J, editors. Perceived Quality. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization Quality of care: a process for making strategic choices in health systems WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2006Available from: http://www.who.int/management/quality/assurance/QualityCare_B.Def.pdfAccessed October 14, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality National health care disparities report 2011Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqr11/nhqr11.pdfAccessed October 14, 2013

- 36.Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization The Principles of Quality Assurance Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization; 1983Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/euro/r&s/EURO_R&S_94.pdfAccessed October 14, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walshe K, Dineen M. Clinical Risk Management. Making a Difference? Birmingham, UK: The NHS Confederation, University of Birmingham; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Misani N. Introduction to Risk Management. Milan, Italy: EGEA; 1994. Italian. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vincent C. Risk, safety and the dark side of quality. BMJ. 1997;314:1775–1776. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7097.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker JS, Wilson M. Clinical risk management in anaesthesia. Qual Health Care. 1995;4:115–121. doi: 10.1136/qshc.4.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pradhan M, Edmonds M, Runciman WB. Quality in healthcare: process. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2001;15:555–571. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kavaler F, Spiegel AD. Risk Management in Health Care Institutions. A Strategic Approach. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang A, Schyve PM, Croteau RJ, O’Leary DS, Loeb JM. The JCAHO patient safety event taxonomy: a standardized terminology and classification schema for near misses and adverse events. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17:95–105. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar S, Steinebach M. Eliminating US hospital medical errors. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2008;21:444–471. doi: 10.1108/09526860810890431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhutani VK, Johnson L. A proposal to prevent severe neonatal hyper-bilirubinemia and kernicterus. J Perinatol. 2009;29:S61–S67. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trucco P, Cavallin M. A quantitative approach to clinical risk assessment: the CREA method. Saf Sci. 2006;44:491–513. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verbano C, Turra F. A human factors and reliability approach to clinical risk management: evidence from Italian cases. Saf Sci. 2010;48:625–639. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verbano C, Venturini K. Development paths of risk management: approaches, methods and fields of applications. J Risk Res. 2001;14:519–550. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stuart G. Taguchi Methods: A Hands-on Approach. New York, NY: Addison Wesley; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cosmin D, Stanciuc AM. Cost of quality and Taguchi loss function. Annals of Faculty of Economics. 2013;1:1479–1485. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Øvretveit J, Tolf S.The costs of poor quality and adverse events in health care – A review of research for the Swedish healthcare compensation insurance company Stockholm, Sweden: The Medical Management Centre, The Karolinska Institutet; 2009Available from: http://www.patientforsakring.se/resurser/dokument/patientsakerhet/_OvretTolfCostAEsafety9Oct09.pdfAccessed October 14, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Varkey P, Kollengode A. A framework for healthcare quality improvement in India: the time is here and now! J Postgrad Med. 2011;57:237–241. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.85222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Radnor ZJ, Holweg M, Waring J. Lean in healthcare: the unfilled promise? Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schweikhart SA, Dembe AE. The applicability of lean and six sigma techniques to clinical and translational research. J Investig Med. 2009;57:748–755. doi: 10.231/JIM.0b013e3181b91b3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Varkey PK, Reller M, Resar RK. Basics of quality improvement in health care. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2006;82:735–739. doi: 10.4065/82.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kruskal JB, Reedy A, Pascal L, Rosen MP, Boiselle PM. Quality initiatives: lean approach to improving performance and efficiency in a radiology department. Radiographics. 2012;32:573–587. doi: 10.1148/rg.322115128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Facts about the Joint Commission 2006Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/Facts_The_Joint_Commission.pdfAccessed October 14, 2013

- 59.Bertolaccini L, Rizzardi G, Filice MJ, Terzi A. Six Sigma approach – an objective strategy in digital assessment of postoperative air leaks: a prospective randomised study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:e128–e132. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feng Q, Manuel CM. Under the knife: a national survey of six sigma programs in US healthcare organizations. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2008;21:535–547. doi: 10.1108/09526860810900691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harrington H, Trusko B. Six Sigma: an aspirin for health care. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2005;18:487–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Souza LB. Trends and approaches in lean health care. Leadersh Health Serv (Bradf Engl) 2009;22:121–139. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Laursen M, Gertsen F, Johanson J. Applying Lean Thinking in Hospitals – Exploring Implementation Difficulties. Aalborg, Denmark: Center for Industrial Production, Aalborg University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mazzocato P, Savage G, Brommels M, et al. Lean thinking in healthcare: a realist review of the literature. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:376–382. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.037986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Health at a Glance: Europe 2012 Available from: http://www.oecd.org/health/healthataglanceeurope.htmAccessed October 14, 2013

- 66.Womack JP, Jones DT. Lean Thinking – Banish Waste and Create Wealth in your Corporation. New York, NY: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reason JT. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000;320:768–770. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ohno T. Toyota Production System, Beyond Large-Scale Production. Boca Raton, FL: Productivity Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Crema M, Verbano C. Health lean management and clinical risk management: a systematic literature review; Proceedings of the 6th Annual EuroMed Conference. Confronting Contemporary Business Challenges through Management Innovation; Lisbon, Portugal. September 23–24, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Printezis A, Gopalakrishnan M. Current pulse: can a production system reduce medical errors in health care? Qual Manag Health Care. 2007;16:226–238. doi: 10.1097/01.QMH.0000281059.30355.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Biffl WL, Beno M, Goodman P, et al. Leaning the process of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37:99–109. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Holden RJ. Lean thinking in emergency departments: a critical review. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sunyog M. Lean management and Six-Sigma yield big gains in hospital’s immediate response laboratory. Quality improvement techniques save more than $400,000. Clin Leadersh Manag Rev. 2004;18:255–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vats A, Goin M, Villarreal T, et al. The impact of a lean rounding process in a pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:608–617. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232e2fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Petroni G, Venturini K, Verbano C. Open innovation and new issues in R&D organization and personnel management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2012;23:147–173. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shah R, Ward PT. Defining and developing measures of lean production. Journal of Operations Management. 2007;25:785–805. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shah R, Ward PT. Lean manufacturing: context, practice bundles, and performance. Journal of Operations Management. 2003;21:129–149. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dahlgaard JJ, Dahlgaard-Park SM. Lean production, Six Sigma quality, TQM and company culture. The TQM Magazine. 2006;18:263–281. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bhasin S, Burcher P. Lean viewed as a philosophy. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management. 2006;17:56–72. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mann D. Creating a Lean Culture: Tools to Sustain Lean Conversions. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dal Corso L, De Carlo NA, Salmaso L. Risk management, quality and safety in healthcare. In: De Carlo NA, Faa G, Rutelli P, editors. Humanization and Health Occupation. Communication, Organisation and Territory. Milan, Italy: Franco Angeli; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cagliano A, Grimaldi S, Rafele C. A systemic methodology for risk management in healthcare sector. Saf Sci. 2011;49:695–708. [Google Scholar]