Abstract

Emerging and reemerging viral diseases of livestock and human beings are in sharp rise in recent years. Importantly, many of these viruses, including influenza, Hendra, Nipah and corona are of zoonotic importance. Several viral diseases of livestock such as bluetongue, peste des petits ruminants, camel pox, equine infectious anaemia, chicken anaemia and sheep-associated malignant catarrhal fever are crossing their traditional boundaries. Emergence of new serotypes and variant forms of viruses as in the case of blue tongue virus, avian infectious bronchitis virus, Newcastle disease virus adds additional level of complexity. The increased incidence of emerging and reemerging viral diseases could be attributed to several factors including deforestation and surge in direct contact of livestock and humans with wild animals and birds. This special issue of “Indian Journal of Virology” is focused on diverse aspects of above diseases: isolation and characterization of viruses, epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention measures and vaccine development.

Keywords: Virus, Emergence, Livestock, Diagnosis, Vaccines, Adjuvants, Pathogenesis

Last few decades have witnessed a sharp rise in the number of emerging and reemerging viral diseases of livestock and human. Some of the examples include hemorrhagic fevers caused by diverse viruses such as Marburg (1967), Lassa (1969), Hanta (1970), and Ebola (1976); encephalitis and respiratory diseases caused by Henipaviruses (Hendra in 1994 and Nipah in 1999); respiratory diseases caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS 2002), Hanta (1993), middle-east respiratory syndrome (MERS 2012) and influenza (A/H5N1 in 2005, A/H1N1 in 2009 and A/H7N9 in 2012) viruses; reproductive syndromes caused by Schmallenburg virus (2011); acquired immunodeficiency syndrome caused by HIV (1981) as well as hepatitis C virus (1989) and a bunyavirus associated with fever and thrombocytopenia (2009). Importantly, many of these viruses, including influenza, Hendra, Nipah and corona are of zoonotic importance. In addition, several historically well known viral diseases such as foot and mouth disease, rabies, chikungunya, dengue, Rift Valley fever, yellow fever, West Nile fever and enteroviral encephalitis are reemerging and certain other viral diseases such as bluetongue and peste des petits ruminants are crossing their traditional boundaries and expanding their territory. Emergence of new serotypes and variant forms of viruses add additional level of complexity [2, 3, 7–10, 12, 14].

The increased incidence of viral diseases could be attributed to several factors. First and foremost is deforestation and the surge in direct contact of livestock and humans with wild animal species. As a matter of fact, most of the viral diseases listed above originated from wild animals and birds. Global expansion of cultivating land, population growth, intensive industrialization, changes in the atmosphere, the life-cycle and the movement of viral vectors, illegal and unscrupulous trade practices, and curbing the reporting of disease outbreaks are additional reasons. All these viral diseases are not only threatening livestock and human health, but also causing considerable losses to economy, trade and global travel. With nearly two-thirds of the global population (both human and livestock) living in the developing countries, it is not surprising to see that most of the emerging viral diseases originate from these regions. Unfortunately, many such unalarming incidences have developed into regionally serious or widespread or even pandemic diseases. Therefore, international cooperation, as well as scientific and political determinations are required to combat emerging viral diseases.

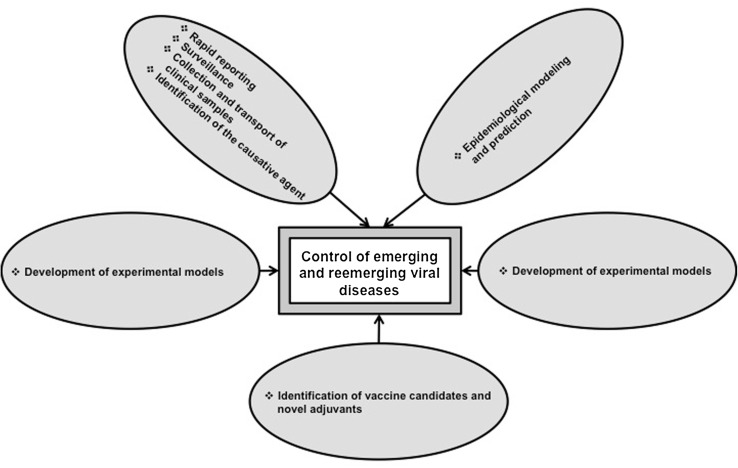

An effective fight against emerging and remerging viral diseases requires multidisciplinary approaches that include rapid reporting, surveillance, collection and transport of clinical samples and identification of the causative agent, epidemiological modeling and prediction, development of experimental models, strengthening the basic research and identification of vaccine candidates and novel adjuvants (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Multidisciplinary approaches to combat emerging and remerging viral diseases

Rapid reporting, surveillance, collection and transport of clinical samples and identification of the causative agent

Prompt implementation of these procedures has helped in quick identification of the etiology as well as expeditious application of control measures in case of SARS, MERS, and H5N1, H1N1 and H7N9 influenza outbreaks in various parts of the world as well as bluetongue disease caused by serotype 8 virus in Europe. However, in most of the developing countries such practices only remain as policies. As a consequence, reemergence of an old virus or emergence of a novel virus is only uncovered when the disease has spread widely.

Epidemiological modeling and prediction

Infected population and patients provide valuable data regarding spread of the virus, pathogenesis of disease and immune response to the virus. These information need to be supported by robust modeling and prediction programs. This can only be achieved by assembling multidisciplinary teams, which include clinicians/veterinarians, virologists, pathologists, epidemiologists, statisticians and field workers. Of note, during outbreak of foot and mouth disease in United Kingdom during 2001, three different models were utilized to predict the progression of disease and to take appropriate control measures [6].

Development of experimental models

Several viral diseases, including chikungunya and dengue, lack appropriate experimental animal models that closely mimic the disease in natural hosts. The main reasons are inability of the viruses to infect and replicate in experimental animals and differences in the immune system of natural host versus experimental animals. To address these limitations, humanized mouse models have been developed. Such models would greatly assist designing of prevention programs, prophylaxis and therapeutic strategies, and diagnostic tools. In veterinary virology, similar experimental models play a key role for understanding the pathogenesis of viral diseases of large animals and wild species.

Strengthening the basic research

Most of the technologies arise from basic understanding of disease pathogenesis. Therefore, studies to decipher the molecular and cellular cross-talk between host immune cells and virus, documentation of immune evasive strategies of virus as well as systems biology approaches must be supported without bias. As compared to progress in humans, the immune system of domestic and wild animals is not yet explored in depth. In particular, the detailed phenotype and molecular analysis of antigen presenting cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages; the T cell subsets and B cells are lacking. This constitutes a major hurdle for developing effective control measures in livestock, and it can have a spillover effect in the case of zoonotic diseases.

Identification of vaccine candidates and novel adjuvants

Despite our success in eradicating or controlling a handful of diseases, infectious diseases remain a grave concern to human and animal life and productivity. Importantly, more research is needed on vaccines and adjuvants, which induce rapid and long-lasting protective immune responses. Unlike bacterial vaccines, viral vaccines should induce both cellular and humoral immunity. While cellular immune responses clear virus-infected cells and reduce virus burden, humoral responses neutralize cell-free viruses. Although oil adjuvants have replaced alum in most of the current veterinary vaccines, further work is necessary to identify adjuvants with precise cellular and molecular mechanisms, to improve vaccine delivery systems and to promote new generation vaccines. Some of the recent inventions in human vaccinology and immunology could be considered for further exploration in veterinary virology. They include microneedle-based vaccine delivery systems, and adjuvants that target toll-like receptors, immunosuppressor cells such as regulatory T cells [1, 4, 5, 11, 13]. Advancements in the domain of foot and mouth disease virus could serve as an example and inspiration in this regard. However, cost-effective analysis of such new approaches is mandatory.

This special issue of “Indian Journal of Virology” on “Emerging viral diseases of livestock in the developing world” is aimed at providing insights on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, immunity, vaccines and experimental models pertaining to emerging viral diseases. The Editorial Board of the “Indian Journal of Virology” thanks all the contributors and reviewers for their efforts and support.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. N. R. Hegde for the critical reading.

Jagadeesh Bayry

is a senior scientist at Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (French National institute of Health and Medical Research, INSERM), Paris, France. His research is aimed at deciphering cellular and molecular interaction of innate and adaptive immune compartment in physiopathologies and dissection of immune evasion strategies of pathogens. Dr. Bayry performed the role of a guest editor for this special issue of Indian Journal of Virology.

References

- 1.Aimanianda V, Haensler J, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Kaveri SV, Bayry J. Novel cellular and molecular mechanisms of induction of immune responses by aluminum adjuvants. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayry J, Goudar MS, Nighot PK, Kshirsagar SG, Ladman BS, Gelb J, Jr, Ghalsasi GR, Kolte GN. Emergence of a nephropathogenic avian infectious bronchitis virus with a novel genotype in India. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:916–918. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.916-918.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganesh B, Banyai K, Kanungo S, Sur D, Malik YS, Kobayashi N. Detection and molecular characterization of porcine picobirnavirus in feces of domestic pigs from Kolkata, India. Indian J Virol. 2012;23:387–391. doi: 10.1007/s13337-012-0106-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guy B. The perfect mix: recent progress in adjuvant research. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:505–517. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hegde NR, Kaveri SV, Bayry J. Recent advances in the administration of vaccines for infectious diseases: microneedles as painless delivery devices for mass vaccination. Drug Discov Today. 2011;16:1061–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keeling MJ, Woolhouse ME, Shaw DJ, Matthews L, Chase-Topping M, Haydon DT, Cornell SJ, Kappey J, Wilesmith J, Grenfell BT. Dynamics of the 2001 UK foot and mouth epidemic: stochastic dispersal in a heterogeneous landscape. Science. 2001;294:813–817. doi: 10.1126/science.1065973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khanna M, Kumar B, Gupta A, Kumar P. Pandemic influenza A H1N1 (2009) virus: lessons from the past and implications for the future. Indian J Virol. 2012;23:12–17. doi: 10.1007/s13337-012-0066-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kong WL, Huang YM, Cao N, Qi HT, Huang LZ, Zhao MM, Guan SS, Wang WH, Zhao FR, Qi WB, Jiao PR, Zhang GH. Isolation and phylogenetic analysis of H1N1 swine influenza virus from sick pigs in Southern China. Indian J Virol. 2011;22:66–71. doi: 10.1007/s13337-011-0035-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nichol ST, Arikawa J, Kawaoka Y. Emerging viral diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12411–12412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.210382297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao PP, Reddy YV, Meena K, Karunasree N, Susmitha B, Uma M, Prasad PU, Chaitanya P, Reddy YN, Hegde NR. Genetic characterization of bluetongue virus serotype 9 isolates from India. Virus Genes. 2012;44:286–294. doi: 10.1007/s11262-011-0707-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rueckert C, Guzman CA. Vaccines: from empirical development to rational design. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003001. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh RK, Balamurugan V, Bhanuprakash V, Venkatesan G, Hosamani M. Emergence and reemergence of vaccinia-like viruses: global scenario and perspectives. Indian J Virol. 2012;23:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s13337-012-0068-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan SP, Koutsonanos DG, Del Pilar Martin M, Lee JW, Zarnitsyn V, Choi SO, Murthy N, Compans RW, Skountzou I, Prausnitz MR. Dissolving polymer microneedle patches for influenza vaccination. Nat Med. 2010;16:915–920. doi: 10.1038/nm.2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]