ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Driving for older adults is a matter of balancing independence, safety and mobility, and prematurely relinquishing the car keys can impact morbidity and mortality. Discussions about “when to hang up the keys” are difficult for clinicians, drivers, and family members, and therefore are often avoided or delayed. “Advance Driving Directives” (ADDs) may facilitate conversations between health care providers and older drivers focused on prevention and advance planning for driving cessation.

OBJECTIVE

To examine clinician and older driver perspectives on ADDs and driving discussions.

DESIGN

Qualitative descriptive study using iterative focus groups and interviews with clinicians and drivers.

PARTICIPANTS

(1) Eight practicing internal medicine physicians, physician assistants or nurse practitioners working at three university-affiliated clinics; and (2) 33 community-dwelling current drivers aged 65 years or older.

APPROACH

Theme analysis of semi-structured focus groups and interviews with clinicians and older drivers was used to explore clinician and driver perspectives on “ADDs” and driving conversations. General inductive qualitative techniques were used to identify barriers and facilitators to conversations between older drivers and their healthcare providers about driving and health.

KEY RESULTS

Five dominant themes emerged: (1) clinicians usually initiate conversations, but typically not until there are “red flags;” (2) drivers are open to conversations, especially if focused on prevention rather than interventions; (3) family input influences clinicians and drivers; (4) clinical setting factors like short appointments affect conversations; and (5) both clinicians and drivers thought ADDs could be useful in some situations and recommended making general questions about driving a part of routine care.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians and older drivers often wait to discuss driving until there are specific “red flags”, but both groups support a new framework in which physicians routinely and regularly bring up driving with patients earlier in order to facilitate planning for the future.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2498-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: older driver, physician, anticipatory guidance, Advance Driving Directive, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

With the growth of the older adult population has come increased attention to the question of when to “hang up the car keys.” The difficulty lies in balancing safety, mobility and independence: fatal crash rates per mile travelled increase after age 75,1 but premature driving cessation is associated with morbidity and early mortality.2–10 Thus, the challenge is to understand how and when to identify at-risk older drivers without limiting the mobility of those who are safe.10–13 Efforts to keep older drivers safe but mobile10,14,15 are complicated, because cognitive, physical and sensory impairments, and their treatments, can affect driving.2,16,17

Healthcare providers have a leading role in issues related to older drivers,18 because they are trusted by patients and their families19–21 and have obligations related to patient and community safety.18,22 However, most clinicians receive no focused training concerning older driver assessment and may be reluctant to have these often emotional, difficult discussions.

The question of how to balance older adult mobility and safety has additional importance, because of work showing most adults outlive their driving ability by 6 to 10 years.5 However, the paucity of affordable, acceptable transportation options23 may contribute to a propensity to continue driving beyond a period of safe skills.24 Recognizing that driving cessation is an inevitability for many older drivers, we previously explored the concept of “Advance Driving Directives” (ADDs)20,21 as a way for clinicians, families and older drivers to prepare for future mobility changes. Although not legally binding, these forms could facilitate conversations about drivers’ preferences for future testing or decision-making assistance (Appendix, available online).

In this investigation, we sought to use qualitative methods to explore the topic of advance mobility planning and to identify barriers and facilitating factors to driving discussions between older drivers and their providers, including a potential role for ADDs.

METHODS

Study Population

Eligible clinicians were English-speaking practicing physicians, physician assistants or nurse practitioners at three university-affiliated outpatient clinics (one geriatric, two general internal medicine) in Colorado. Clinicians were recruited via flyers in the clinics and emails from clinic directors and received lunch and a $5 gift card for participating.

Eligible drivers were English-speaking adults aged ≥ 65 years who reported driving in the last 30 days and lacked significant cognitive impairment (i.e., able to give informed consent as determined by research staff). Drivers were recruited via flyers posted at an independent living facility (ILF; 2,600 units) and a local community Senior Center, as these settings provided access to a population of generally healthy, independent and mobile older adults. Participating drivers received snacks and a $10 gift card, and driver focus groups were held in an ILF or Senior Center conference room.

The driver focus groups lasted 90–120 min, and the clinician focus group and all interviews lasted 30–60 min. Interviewees were clinicians or drivers who were unable to attend the focus group, but still wanted to participate. The interviews were held after the focus groups and explored issues that arose in the groups.

Study Design

A qualitative descriptive study design25 was the most appropriate to gain insights related to the context of driving decisions. Perspectives are influenced by differing values and perceived consequences, so clinician and driver focus groups were held separately to allow for homogenous group interactions to deepen understandings. All sessions used open-ended questions informed by a semi-structured guide developed from existing literature and research questions (Appendix, available online). Through an iterative approach,26,27 material from early groups and interviews was analyzed and used to inform and deepen subsequent discussions.

Each focus group had a facilitator and a note-taker, and interviews had either one or two investigators present. The investigators did not have preexisting relationships with participating clinicians or drivers, but they introduced themselves at the start of the session and described the study’s goal as improving communication and enhancing older adult safety and mobility. Sessions were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by research staff for subsequent coding and analysis. Field notes written during the groups and interviews captured nonverbal cues, group interactions, and in-the-moment global understanding of participant responses. Focus groups and interviews were conducted from March 2012 to May 2012. All participants provided informed consent and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

We used a team-based analytic approach informed by established inductive and deductive techniques28–33 and guided by a senior qualitative researcher (JJ). Analyzed material included session transcripts, debriefing conversations with the research team, and field notes from interviews and focus groups. Field notes provided holistic insights from the time of interviews and group discussions and were considered a starting point of the intertwined “parts and whole” analytic structure.30 Notes from team discussions held immediately after the sessions included dominant impressions.

Two investigators (MEB and EP) independently manually analyzed the material using a step-wise approach. The interview guide provided predetermined deductive codes, and new inductive codes emerged from participants’ words and their context. We considered these codes together for similarities and differences, and we resolved discrepancies through team consensus using an iterative process and regular team discussions. We used Atlas.ti V6.2 to facilitate analysis through visual mapping of code and theme structures and searches for connected theme strings or families, a strategy that facilitates pattern recognition in grasping the whole of the data.28,30,34

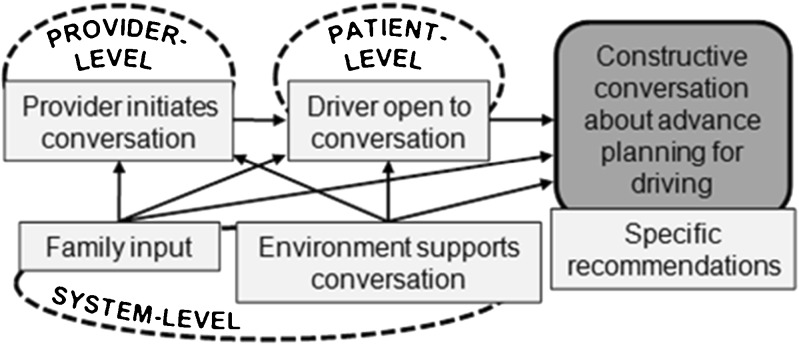

We synthesized the codes into a core set of themes, and using our inductive and deductive toolkit,31,32 we compared and contrasted our themes with our first cycle of direct speech coding. We organized the final core themes into a diagram representing a preliminary framework about conversations related to driving and advance planning for mobility changes (Fig. 1). Together, these processes provided an in-depth comprehensive analytic matrix for interpretation,27,28,30,32 and the multidisciplinary team provided multiple perspectives through which to interpret the text data. We also shared the themes and framework with participants during the last set of interviews to check thematic organization.

Figure 1.

Preliminary framework of clinician-driver interactions concerning constructive conversations about advance planning for driving. Dominant themes from this study (light grey boxes) are shown in context of provider-level, patient-level and system-level factors (dashed ovals).

RESULTS

We conducted one clinician focus group (five participants), three clinician interviews, two driver focus groups (16 and 14 participants), and three driver interviews (Table 1), which together yielded 231 pages of transcript data and ten pages of notes. We stopped recruitment when analysis suggested “thematic saturation,” with no new themes arising from the data.27,28 A general framework emerged from the data that centered on barriers and facilitators to constructive conversations about advance planning for driving decisions (Fig. 1). Within this framework, there were five dominant, sometimes overlapping, themes: (1) clinician initiation of conversations; (2) driver openness to conversations; (3) family influences; (4) clinical setting factors; and (5) specific recommendations for improved conversations (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Focus Group and Interview Participants

| Drivers (n = 33) | Clinicians (n = 8) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (median, IQR) | 80 (75–84.5) | 43.5 (41.5–46) |

| Female (n, %) | 30 (91) | 5 (62.5) |

| Number of years driving (median, IQR) | 60 (50–64) | – |

| Number of years practicing medicine (median, IQR) | – | 13.5 (9–15) |

IQR Interquartile range

Table 2.

Representative Quotes, by Emergent Theme and Participant Group

| Theme | Clinicians | Older drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Clinician initiation of conversation | “I don’t really discuss this with most of my patients.” | “I think it is a question doctor should be asking you, as you age, he should say, ‘do you feel comfortable driving, do you have any problems you think you might have that you shouldn’t be driving?” I think it would be good to ask that.” |

| “The conversation is almost always either initiated by myself…or occasionally by concerned family members, hardly ever initiated by the patient.” | ||

| Driver openness to conversation | “Patients would be receptive, so long as it was in the abstract.” | “I would want her to say are you still driving? And if she said you are losing your motor skills, have you ever thought about maybe it’s time not to be driving? I would listen.” |

| Family influences | [They’re] “looking for us to support them, or to be the bearer of that bad news.” | “’Oh no, don’t take my keys!’ But I hope to … make the decision myself.” |

| “I rely heavily on what the family says.” | “I don’t have anyone to have [an ADD] with.” | |

| Clinical setting factors | [We need] “more reasonable options for people who are not going to drive anymore.” | “With a primary care doctor, your appointment is usually scheduled for 15 or 20 min, he’s not going to take 5 or 10 min out of that to discuss your driving.” |

| “I never have time for anything.” | ||

| Recommendations | “Say, ’10 years from now and you’re not able to drive, what would your plan be, whom would you ask, or when do you think for yourself that driving is not a good option?’ I would like to get their say about it, so that they are more compliant and more agreeable to that idea of when they come to that stage.” | “They could say ‘this is part of our prevention policy here,’ and introduce it that way.” |

Clinician Initiation of Conversations

The dominant provider-level finding was that clinicians felt they were the ones to usually begin driving discussions with older patients. Typically, they did not initiate these conversations until there was already a concern, either from a family member, change in the patient’s health, or other “red flag” event like a crash. Some clinicians noted that general driving discussions were unplanned and unusual: “I don’t really plan in advance.” Clinicians identified the barrier of concerns about negative reactions from patients; one clinician said: “I’ve never had one person take it well. …They feel punished and in many ways you’re taking away all their independence, so it’s a significant threat.” An additional barrier to driving conversations included clinician uncertainty about local transportation options or reporting requirements.

However, clinicians recognized their role in counseling older drivers, including ethical and legal obligations and “how important it is to deal with these things with our patients.” They noted that some common circumstances, like filling out disability permits, could be an opportunity for discussing driving. Many clinicians identified with a role in recommending testing or driving cessation, especially after prompting by family members: “That’s my job, to be the bad guy.”

Clinicians commented that driving safety fit with other health promotion and injury prevention activities. One said, “If my goals are to help them be independent, then safe driving is very important. And…if I’m caring about cognitive improvement, driving and overall safety including wandering, or are there guns in the house, those things are all things that I should be assessing.” Drivers also recognized clinicians’ role in health promotion; as one driver responded when asked if it would seem strange to be asked by their provider about driving, “They ask me everything else.”

Clinicians and drivers agreed that driving discussions are best when there is an established clinician–patient relationship. As one clinician said, a person who needs driving guidance “shouldn’t be seeing anyone other than their PCP who knows them best.”

Driver Openness to Conversations

The primary patient-level finding was that drivers were generally open to clinician questioning and saw clinicians as “fair-minded:” “I don’t think they are out to get anybody. Or take any privilege away from you that you don’t deserve to have taken.” However, the majority felt that their clinicians were generally unaware of their patients’ driving status or ability. In one driver focus group, when asked if their primary care clinician knew if they were currently driving, all participants said “no.”

Drivers identified some of the same barriers to conversations as clinicians, including time constraints and competing priorities. They also noted some themes identified in prior studies, including driving as a symbol of independence and limited alternative transportation options. When discussing decisions about driving cessation, driver opinions were mixed. Some noted they would be open to clinician recommendations, especially if based on objective evidence, but others felt it was a personal decision often based on “common sense.” Many drivers noted that some patients would be more open to conversations than others: “There are always going to be people who aren’t going to cooperate.”

When asked about the idea of ADDs, drivers were open to the idea of advance planning with their clinicians. As one participant said: “So there’s going to be more of us driving. And with preventative care, we’re going to be living longer … so I think it would really be an advantage to doctors to be comfortable in talking to this.” Drivers expressed concerns over being a “burden” to family members and finding convenient alternative transportation, and they thought that advance planning might mitigate some of these stresses. Many drivers also identified advantages to stopping driving, including saving money.

Family Influences on Clinician-Driver Conversations

Both clinicians and drivers commented on family involvement in making decisions about driving cessation. Clinicians noted that driving conversations with older drivers often arise because a family member reports a concern. Clinicians commented that families are often “looking for support,” and may want “the doctor to take the keys away.” While clinicians valued family input, they were also cautious about family discussions without the patient present (it “feels bad to a person to have people talking about them behind their back”).

Drivers also felt family input was common and important. Many drivers related that their family members would take them on “test drives,” and one woman said “my children joke about who is going to get mom’s keys when it’s time.” Like clinicians, drivers saw a smaller role for family members in routine preventive conversations with clinicians about driving, and many said they often go to appointments without a family member.

Both clinicians and drivers noted the family’s role depended on the frequency of contact. As a driver said: “If you have a son or daughter to visit you regularly, I think their input is very important.” Many drivers commented that it was important clinicians not depend too much on family members, since many older drivers are single, childless, or otherwise lacking involved family members.

Clinical Setting Factors

Both clinicians and drivers commented on system-level issues related to the clinical setting in which driving discussions occur, including time constraints and competing priorities. Concerning adding driving questions to routine patient questionnaires, one physician noted that he already gets “so many complaints from patients about how many questions they have to answer.” However, many drivers were hopeful that healthcare reform might support inclusion of more preventive conversations or services.

Clinicians commented on the importance of support staff, including medical assistants for initial screening. While drivers were generally open to the idea of a paper form with standard questions or screening by a medical assistant, clinicians were concerned about “more and more things the [medical assistants] have to put in the chart.” Clinicians appreciated having help from social workers for resources and family discussions: “And frankly we don’t have a ton to offer [patients]. I can offer access-a-ride, but that is limited by…my not knowing exactly if it meets their needs. … My social worker is really helpful in actually getting the application started, but then often the patient has to go follow through with getting it.”

Recommendations for Constructive Conversations

A primary theme that emerged from this study was the overall importance of improved communication about driving safety. Both clinicians and drivers supported the idea of regular questioning about driving as a way to make it an easier topic, as patients might be “more receptive if they have heard it once before.” Many mentioned this could be part of the annual Medicare wellness exams, and both groups frequently used the word “routine” in recommendations for clinician questioning about driving. Both drivers and clinicians supported making driving questions standard, so that the inquiries would feel less threatening: “You just turned 70, this is a new thing we’re doing [in the clinic],” or “this is part of our prevention policy here.” Clinicians and drivers also noted the importance of linking these questions to “some sort of patient education…about ways to maintain independence without driving” or to algorithms for additional testing or referrals.

When asked about the concept of ADDs, both clinicians and drivers thought this kind of tool could be useful in beginning advance planning conversations about driving, at least with some drivers. As one clinician said: “I wish we could normalize driving health, just like…in pediatrics we try to help folks think ahead about developmental stages, and I think [an ADD] is maybe a useful tool.” Both clinicians and drivers noted that conversations are less emotionally charged when focused on prevention and held before driving concerns arise. A clinician commented: “For those [for whom] it’s preventative health the stakes are not as high, so they’re often more willing to explore with me when I ask a question, you know, ‘in what circumstances could you see not driving in the future,’ and they’re sort of willing to talk about that.” Similarly, a driver said: “And they’re not telling you that ‘I want you to stop driving right now,’ but they’re saying ‘if you get to the stage where somebody has some concerns, would you listen to that person?’ That’s all [the ADD’s] saying. I think that’s a good idea.” At the same time, both clinicians and drivers recognized that it “differs from person to person” and ADDs might not be useful for some clinicians or patients.

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study sought to examine clinician and older driver perspectives on conversations about advance planning for changes in driving. The dominant theme that emerged was that currently clinicians and drivers avoid discussing driving until specific concerns arise, a finding consistent with prior work.35–39 A novel finding was that, in this sample, both groups thought routine questions about driving or “anticipatory guidance” about mobility changes would be useful.

Many drivers said their clinicians do not even know if they currently drive or not, and many clinicians reported they do not routinely ask about driving. In previous studies, 60–77 % of physicians have reported addressing driving issues with patients22,35 and 70 % of physicians said they had counseled patients to stop driving in the past year,22 confirming that driving issues commonly arise in clinical practice. However, these studies did not specifically question physicians how many patients they ask about driving and may show that physicians discuss issues with at least some patients, if not all. In another study, only 21 % of surveyed American Geriatrics Society members reported keeping records of their patients’ driving status, and most were unaware of guidelines concerning driver assessment.38 While our qualitative study cannot provide a quantitative estimate of how many clinicians routinely ask patients about driving, our findings from this small sample suggest these questions often are not asked until there is a “red flag.”

These findings also suggest a larger issue: provider ignorance concerning important aspects of the social lives of older patients. While primary care providers traditionally have prided themselves on developing close relationships with established patients, our findings suggest gaps in these relationships, at least concerning driving and mobility. These gaps may stem from time constraints, practices where patients see multiple providers, or provider hesitation about talking about driving.22,35,38–40 On the issue of driving, these relationship gaps could be especially problematic, given the way health and mobility affect each other2–10 and the way older patients’ family members often ask providers for help. Thus to optimize older patients’ well-being, providers must work with drivers and their family members to balance competing priorities in mobility, independence, and safety.

To date, there has been little attention to routine questioning concerning driving before there are specific concerns, except in populations such as those with dementia.41 However, such questioning might be a way to improve provider–patient communication about driving. “Anticipatory guidance” is a cornerstone of pediatrics, with specific topics discussed at each preventive visit during childhood.42 The concept has been defined as “information that helps families prepare for expected physical and behavioral changes.”43 Anticipatory guidance is less common in non-pediatric populations; in geriatrics, the most well known example is end-of-life discussions. However, the concept might make sense for older adults, given the physical and mental changes that come with aging, although the timing of these changes is less predictable than in the pediatric population. This anticipatory guidance could include a range of topics,41 such as fall prevention18 and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. For driving in particular, guidance could focus on “red flags” for driving risk, modification of driving practices, and preparation for driving retirement, and this kind of preparatory education could help older adults prepare for or avoid future problems. For example, identification of particular driving issues, such as poor night vision or dizziness after medication use, could help a clinician take steps to mitigate the problem and support continued, safe driving.18

In prior studies, physicians have expressed support for their role in assessing and counseling older drivers.22,38–40,44 However, many report deficiencies in their confidence and skills38–40,44 and concerns over damaging the clinician–patient relationship.35,37,40 Ongoing work is needed to address these knowledge gaps and develop efficient, effective and acceptable protocols for office-based and on-road older driver testing. In the meantime, though, it may make sense to begin routinely questioning older patients about their current driving status. Existing time constraints on primary care visits pose an obstacle, so future work needs to examine the optimal timing and method for such questioning and how driving discussions fit in with other priorities. However, our study participants generally supported the idea of routine questioning for many reasons, including that it was non-threatening, was in line with topics like falls, and could “normalize” the topic to make it easier to discuss. In most cases, asking about driving status would likely not require immediate follow-up questioning or testing, but clinicians need assessments, counseling and resources for those patients who have transportation problems or who may not be safe drivers. Therefore, it will be important to continue efforts to provide appropriate education, guidelines, and support staff.36,45,46

We found that many drivers and clinicians acknowledged that for most people, the day will come when driving is no longer safe. This is consistent with findings from focus groups with patients with dementia and their family members47 and with work showing that most adults outlive their safe driving ability.5 Drivers in our study reported needing help preparing for that transition, including learning about transportation alternatives, which is also in line with prior work.24,47 When asked specifically about the concept of ADDs as an example of a communication tool, drivers and clinicians thought they could be useful for some patients. Prior studies have shown support for physician involvement in these discussions41,47 and for the basic idea of ADDs,20,21 which might be helpful both now (in beginning conversations to plan for eventual driving changes) and in the future (when the time comes to make those changes). Available ADD templates developed for use by family members48,49 could be adapted for clinician use (Appendix, available online).

A limitation of our study is that we included participants from three university-based primary care clinics, one independent living facility and one senior community center, and the participating drivers were generally healthy. The majority of participants were women, but men and women have different driving behaviors and beliefs,19,50,51 so future work will need to target men to better explore their perspectives. In addition, participation was voluntary, and participating physicians and drivers may have been more interested in the topic than nonparticipants in ways that could have affected the results, such as an overestimation of openness to driving discussions. Therefore, our participants’ views may not be reflective of the general populations of either healthcare providers or older drivers. However, we used an iterative study design that enabled new information to be explored for relevance in subsequent group and individual discussions, thus enhancing the rigor of our findings and applicability across clinician-driver situations.27 Our sample size was relatively small, but analysis revealed thematic saturation and participants agreed with our theme organization, suggesting that recruitment was adequate.

Despite these limitations, our study provides useful new information concerning driving conversations between older drivers and clinicians. Most notably, both groups supported routine questioning about driving status as a way to “normalize driving health.” Future work is needed to examine how routine driving questions function in actual clinical care settings. However, “anticipatory guidance” for older drivers could help older adults plan for eventual driving cessation and perhaps avoid some of the emotional, logistical and financial stresses associated with abrupt changes in mobility. It could also make clinicians more comfortable discussing the topic of driving with their older patients, although additional education, assessment protocols, and ancillary support staff for clinicians are still needed.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 23 kb)

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

MEB participated in study concept and design, moderation of focus groups and interviews, transcript analysis and interpretation, and preparation of manuscript, and she takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole. EP participated in study concept and design, moderation of focus groups and interviews, transcription of digital recordings, transcript analysis and interpretation, and preparation of manuscript. RS participated in study concept and preparation of manuscript. JJ participated in study concept and design, moderation of focus groups, transcript interpretation, and preparation of manuscript.

Prior Presentations

Accepted for poster presentation at the 2013 American Geriatrics Society Annual Meeting (Grapevine, Texas).

Funding

This work was supported by the John A. Hartford University of Colorado Denver Center of Excellence. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the John A. Hartford University of Colorado Denver Center of Excellence. No sponsor had any direct involvement in study design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Older Adult Drivers: Get the Facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/Motorvehiclesafety/Older_Adult_Drivers/adult-drivers_factsheet.html. Accessed May 2, 2013.

- 2.Safe Mobility for Older People. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, US Department of Transportation, DOT HS 808 853, 1999. Available at: http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/olddrive/safe/. Accessed May 2, 2013.

- 3.Taylor BD, Tripodes S. The effects of driving cessation on the elderly with dementia and their caregivers. Accid Anal Prev. 2001;33:519–528. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(00)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards JD, Perkins M, Ross LA, Reynolds SL. Driving status and three-year mortality among community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:300–305. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foley DJ, Heimovitz HK, Guralnik JM, Brock DB. Driving life expectancy of persons aged 70 years and older in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1284–1289. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.8.1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ragland DR, Satariano WA, MacLeod KE. Driving cessation and increased depressive symptoms. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:399–403. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marottoli RA, de Leon CFM, Glass TA, Williams CS, Cooney LM, Jr, Berkman LF. Consequences of driving cessation: decreased out-of-home activity levels. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55:S334–S340. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.6.S334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonda SJ, Wallace RB, Herzog AR. Changes in driving patterns and worsening depressive symptoms among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56:S343–S351. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.S343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman EE, Gange SJ, Munoz B, West SK. Driving status and risk of entry into long-term care in older adults. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1254–1259. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Older driver program five-year strategic plan: 2012–2017. Washsington, D.C.: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2010.

- 11.Classen S, Lopez ED, Winter S, Awadzi KD, Ferree N, Garvan CW. Population-based health promotion perspective for older driver safety: conceptual framework to intervention plan. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2:677–693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tefft BC. Risks older drivers pose to themselves and to other road users. J Safety Res. 2008;39:577–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Proceedings of the North American License Policies Workshop. In: Eby DW, Molnar LJ, eds. 2008 June; Washington, DC: AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety; 2008.

- 14.Healthy People 2020: Older Adults. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2011. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=31. Accessed May 2, 2013.

- 15.Focus on Special Populations: Older Adults. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/populations.htm. Accessed May 2, 2013.

- 16.McGwin G, Jr, Sims RV, Pulley L, Roseman JM. Relations among chronic medical conditions, medications, and automobile crashes in the elderly: a population-based case–control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:424–431. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.5.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lotfipour S, Vaca F. Commentary: polypharmacy and older drivers: beyond the doors of the emergency department (ED) for patient safety. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:535–537. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Physician’s Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers, 2nd Edition. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and American Medical Association, 2010. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/433/older-drivers-guide.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2013.

- 19.Tuokko HA, McGee P, Gabriel G, Rhodes RE. Perception, attitudes and beliefs, and openness to change: implications for older driver education. Accid Anal Prev. 2007;39:812–817. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Betz ME, Schwartz R, Valley M, Lowenstein SR. Older adult opinions about driving cessation: a role for advanced driving directives. J Prim Care Commun Health. 2012;3:149–153. doi: 10.1177/2150131911423276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Betz ME, Lowenstein S, Schwartz R. Older adult opinions of “Advance Driving Directives”. J Prim Care Comm Health. 2012; Epub May 16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Drickamer MA, Marottoli RA. Physician responsibility in driver assessment. Am J Med Sci. 1993;306:277–281. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199311000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerschner H, Aizenberg R. Focus group participants reflect on transportation: Transportation tesearch board (Transportation in an Aging Society conference proceedings); 1999.

- 24.King MD, Meuser TM, Berg-Weger M, Chibnall JT, Harmon AC, Yakimo R. Decoding the Miss Daisy Syndrome: an examination of subjective responses to mobility change. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2011;54:29–52. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2010.522231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kvale S, Brinkmann S. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for qualitative data analysis. School of Population Health, University of Auckland. 2003. Available at: http://www.fmhs.auckland.ac.nz/soph/centres/hrmas/_docs/Inductive2003.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2013.

- 29.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 2. Los Angeles: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation. 2009;119:1442–1452. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.742775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guest G, MacQueen KM. Handbook for team-based qualitative research. Plymouth, UK: AltaMira Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adler G, Rottunda SJ. The driver with dementia: a survey of physician attitudes, knowledge, and practice. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2011;26:58–64. doi: 10.1177/1533317510390350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silverstein NM, Murtha J. Driving in Massachusetts: When to Stop and Who Should Decide?: Gerontology Institute Publications; 2001.

- 37.Redelmeier DA, Yarnell CJ, Thiruchelvam D, Tibshirani RJ. Physicians’ warnings for unfit drivers and the risk of trauma from road crashes. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1228–1236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1114310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller DJ, Morley JE. Attitudes of physicians toward elderly drivers and driving policy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:722–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb07460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bogner HR, Straton JB, Gallo JJ, Rebok GW, Keyl PM. The role of physicians in assessing older drivers: barriers, opportunities, and strategies. J Am Board Fam Med/Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17:38–43. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.17.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jang RW, Man-Son-Hing M, Molnar FJ, et al. Family physicians’ attitudes and practices regarding assessments of medical fitness to drive in older persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:531–543. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0043-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perkinson MA, Berg-Weger ML, Carr DB, et al. Driving and dementia of the Alzheimer type: beliefs and cessation strategies among stakeholders. Gerontologist. 2005;45:676–685. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sens AE, Connors K, Bernstein HH. Anticipatory guidance: making it work for your patients and your practice. Pediatr Ann. 2011;40:435–441. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20110815-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan P. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children and Adolescents. 3. Elk Grove Village: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marshall S, Demmings EM, Woolnough A, Salim D, Man-Son-Hing M. Determining fitness to drive in older persons: a survey of medical and surgical specialists. Can Geriatr J. 2012;15:101–119. doi: 10.5770/cgj.15.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marottoli RA. New laws or better information and communication? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:100–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berg-Weger M, Meuser TM, Stowe J. Addressing individual differences in mobility transition counseling with older adults. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2013;56:201–218. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2013.764374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adler G. Driving decision-making in older adults with dementia. Dementia. 2010;9:45–60. doi: 10.1177/1471301209350289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agreement with My Family about Driving. The Hartford Financial Services Group, 2010. Available at: http://www.thehartford.com/sites/thehartford/files/DrivingAgreement.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2013.

- 49.Family Driving Agreement. Keeping Us Safe, 2011. Available at: http://keepingussafe.org/linked/familydrivingagreement100111.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2013.

- 50.Blanchard RA, Myers AM, Porter MM. Correspondence between self-reported and objective measures of driving exposure and patterns in older drivers. Accid Anal Prev. 2010;42:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tuokko H, Myers A, Jouk A, Marshall S, Man-Son-Hing M, Porter MM, Bédard M, Gélinas I, Korner-Bitensky N, Mazer B, Naglie G, Rapoport M, Vrkljan B. Associations between age, gender, psychosocial and health characteristics in the Candrive II study cohort. Accid Anal Prev. 2013; ePub Mar 4. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 23 kb)