Abstract

Purpose

To estimate the incidence of suspected ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) by Region in Tanzania and learn where these lesions are treated.

Methods

We performed an analysis of existing theater records from three Tanzanian referral hospitals from 2006 to 2008 plus a prospective analysis of records from all other eye health workers who remove suspected OSSN outside the referral hospitals over 1 year.

Results

Approximately 40% of suspected OSSN are operated on outside of referral hospitals. The estimated annual incidence of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Tanzania was 2.2 per 100,000 persons. Regional incidence rates were significantly correlated with Regional HIV (Human immunodeficiency virus) prevalence (Pearson’s r = 0.53, P = 0.03).

Conclusion

The incidence rate is high, in line with estimates from other East African countries. Management of these cases requires improvement as most patients are still not tested for HIV.

Keywords: Tanzania, HIV/AIDS, Ocular surface squamous neoplasia, Conjunctiva squamous cell carcinoma, Epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

A sharp rise in the incidence of ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) has occurred in several African countries along with the rise in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) prevalence and OSSN may be the most common ocular manifestation of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa.1–6 Estimates of the incidence of the tumor in the era of HIV/AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome), using cancer registry data from major urban centers in Uganda and Zimbabwe have been published.7, 8 However in most sub-Saharan African countries it is impossible to know how many people with this condition are treated outside urban centers without ever being entered into cancer registries. The aim of the present study was to obtain data on how OSSN is treated across Tanzania and to make an estimate of the incidence of OSSN by region.

METHODS

OSSN is a lesion with no recognized tendency to regress spontaneously. Therefore we assumed that the majority of cases will present for surgical removal eventually, although some patients may die before presentation. We used two different approaches to estimate incidence; one for cases operated at the three main referral hospitals with eye services in Tanzania and another for cases operated outside these. The latter include government or non governmental district hospitals as well as regional hospitals, and will all be referred to as regional hospitals. The three referral hospitals were the Comprehensive Community Based Rehabilitation of Tanzania (CCBRT) Hospital and the Muhumbili National Hospital in Dares-Salaam and the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC) Hospital in Moshi. At these hospitals we collected data on the number of suspected OSSN lesions removed, date, region of residence, and HIV status from 2006 to 2008. Patients were identified from the operating theater registers in each hospital and additional data were collected from the patient files if needed. We used this to calculate an average annual referral-hospital incidence for each region.

Second, we provided training on recognition, referral, and reporting of OSSN for all eye health workers who provide any eye surgery outside the referral hospitals. This included discussions and demonstration of differences in typical clinical appearance among various common conjunctival lesions, particularly pterygia, pinguecula and OSSN. Health workers were encouraged to refer cases of suspected OSSN for excision biopsy if possible, but to excise completely with wide surgical margins if it was not possible for the patient to travel to a referral hospital. Following training, we monitored the number of suspected cases that were operated for the remaining study period (6–14 months) to calculate an annual regional-hospital incidence.

The average annual regional-hospital and annual average referral-hospital rates were added to estimate an annual incidence for each region. These were standardized for 100,000 population in the region. Incidence estimates were entered into STATA 10 along with the HIV prevalence (percentage of HIV positive among people 15–49 years9) in the regions. The Pearson correlation coefficient between these was calculated.

This work was granted ethical approval by the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre ethics committee and follows the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

A total of 921 patients were identified at three referral hospitals (Table 1). Most patients, 805 (87.4%), were aged below 50 years and 562 (61.0%) of the patients were female. Ninety- three (10.1%) were HIV positive, 66 (7.2%) were HIV negative and 762 (82.7%) were not tested for HIV infection.

TABLE 1.

Description of patients identified by Regional Eye Coordinators (REC) with suspected OSSN (after training) by regions

| Characteristics (% in italics) | Regions |

Total | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arusha | Mwanza | Mara | Singida | Shinyanga | Ruvuma | Rukwa | Tabora | Mbeya | Iringa | Mtwara | Lindi | Dodoma | Tanga | Pwani | ||

| Age | ||||||||||||||||

| ≤ 50 | 44 98 |

60 100 |

45 91.8 |

12 80 |

114 97.4 |

80 98.8 |

45 97.8 |

55 93.2 |

85 85.8 |

55 85.9 |

13 92.9 |

8 100 |

9 81.8 |

43 87.7 |

12 100 |

680 93.3 |

| > 50 | 1 2.0 |

0 0.0 |

4 8.2 |

3 20 |

3 2.6 |

1 1.2 |

1 2.2 |

4 6.8 |

14 14.2 |

9 14.1 |

1 7.1 |

0 0 |

2 18.2 |

6 12.3 |

0 0.0 |

49 6.7 |

| Total | 45 100 |

60 100 |

49 100 |

15 100 |

117 100 |

81 100 |

46 100 |

59 100 |

99 100 |

64 100 |

14 100 |

8 100 |

11 100 |

49 100 |

12 100 |

729 100 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Female | 26 58 |

35 58 |

29 59 |

9 40 |

66 56.4 |

46 57.8 |

31 67.4 |

37 62.7 |

73 73.7 |

42 65.6 |

8 57.2 |

5 62 |

6 54.6 |

37 75.5 |

8 67 |

62.8 |

| HIV Status | ||||||||||||||||

| Positive | 8 18 |

28 47 |

28 57 |

1 7 |

25 21 |

24 30 |

16 35 |

33 56 |

72 73 |

25 39 |

6 43 |

3 37 |

8 73 |

41 84 |

6 50 |

324 44.4 |

| Negative | 0 0 |

1 2 |

1 2 |

0 0 |

33 | 0 0 |

4 9 |

12 20 |

13 13 |

0 0 |

5 36 |

3 37 |

2 18 |

2 4 |

0 0 |

46 6.3 |

| Not tested | 37 82 |

31 51 |

20 41 |

14 93 |

89 76 |

57 70 |

26 56 |

14 24 |

14 14 |

39 61 |

3 21 |

2 26 |

1 9 |

6 12 |

6 50 |

359 49.7 |

| Total | 45 100 |

60 100 |

49 100 |

15 100 |

117 100 |

81 100 |

46 100 |

59 100 |

99 100 |

64 100 |

14 100 |

8 100 |

11 100 |

49 100 |

12 100 |

729 100 |

| Management | ||||||||||||||||

| Operated | 0 0 |

60 100 |

45 92 |

13 87 |

114 97 |

81 100 |

31 67 |

31 52 |

96 100 |

64 100 |

13 93 |

6 100 |

11 100 |

49 100 |

11 92 |

623 85.5 |

| Referred | 45 100 |

0 0 |

4 8 |

2 13 |

3 3 |

00 | 15 33 |

28 48 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

1 7 |

2 0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

1 8 |

106 14.5 |

| Total Suspected | 45 100 |

60 100 |

49 100 |

15 100 |

117 100 |

81 100 |

46 100 |

59 100 |

99 100 |

64 100 |

14 100 |

8 100 |

11 100 |

49 100 |

12 100 |

729 100 |

| Period collected (Months) | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

OSSN: ocular surface squamous neoplasia; REC: Regional Eye Coordinator.

Dar es salaam and Kilimanjaro are not included because all cases in these regions were referred to three referral Hospitals and included in the hospital data.

A total of 63 eye health workers were provided training in three groups by region: the first (Arusha, Mwanza, Mara, Shinyanga, Singida, Tanga, Kilimanjaro) in February 2008; the second (Mbeya, Iringa, Tabora, Rukwa, Ruvuma) in April 2008 and the third (Pwani, Morogoro, Lini, Mtwara, Kigoma) in September 2008. Data were collected from the three groups after training at 14, 12, and 6 months respectively. During these periods a total of 729 patients with suspected OSSN were identified by eye health workers; 623 (85.5%) were operated on in the regions and 106 (14.5%) were referred to one of the three referral hospitals (Table 2). No data or reports were received from four regions (Kagera, Kigoma, Manyara, and Morogoro). Most of the patients, 680 (93.3%), were aged below 50 years and 458 (62.8%) were female. Three hundred twenty four (44.4%) were HIV positive, 46 (6.3%) were HIV negative and 359 (49.3%) were not tested.

TABLE 2.

Description of patients operated at referral hospitals with suspected OSSN by regions

| Characteristics (% in italics) | Regions [n

(%)] |

Total | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arusha | Mwanza | Mara | Singida | Shinyanga | Ruvuma | Rukwa | Tabora | Mbeya | Iringa | Mtwara | Lindi | Dodoma | Tanga | Pwani | Kilimanjaro | Dares-Salaam | Manyara | Morogoro | Kagera | Kigoma | Zanzibar | |||

| Age | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ≤ 50 | 45 88.2 |

3 75. |

5 83. |

5 100 |

7 78 |

0 0 |

5 100 |

8 73. |

9 90 |

7 78 |

4 100 |

7 100 |

5 63 |

24 86 |

34 94 |

123 89 |

457 88 |

16 89 |

23 79 |

1 100 |

8 100 |

9 69 |

805 87.4 |

|

| > 50 | 6 11.8 |

1 25 |

1 17. |

0 0 |

2 22 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

3 27 |

1 10 |

2 22 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

3 37 |

4 14 |

2 6 |

16 11 |

63 12 |

2 11 |

6 21 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

4 31 |

116 12.6 |

|

| Total | 51 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 28 | 36 | 139 | 520 | 18 | 29 | 1 | 8 | 13 | 921 | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Female | 30 58.8 |

2 50 |

2 33 |

4 80 |

4 44 |

0 0 |

3 60 |

5 45 |

8 80 |

6 67 |

3 75 |

6 86 |

6 75 |

18 64 |

18 50 |

93 67 |

315 61 |

9 50 |

17 59 |

1 100 |

5 62 |

7 54 |

562 61.0 |

|

| HIV Status | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Positive | 23 45.1 |

1 25 |

1 17. |

1 20. |

0 0. |

0 0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

1 10 |

1 11 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

1 13 |

3 11 |

1 3 |

46 33 |

4 0.8 |

7 39 |

3 10 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

93 10.1 |

|

| Negative | 16 31.4 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

0 0. |

1 11 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

1 9. |

0 0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

3 11 |

0 0 |

35 25 |

2 0.4 |

7 39 |

13 | 0 0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

66 7.2 |

|

| Not tested | 12 23.5 |

3 75 |

5 83. |

4 80. |

8 89 |

0 0 |

5 100 |

10 91 |

9 90 |

8 89 |

4 100 |

7 100 |

7 87 |

22 78 |

35 97 |

58 42 |

514 99 |

4 22 |

25 87 |

1 100 |

8 100 |

13 100 |

762 82.7 |

|

| Total | 51 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 28 | 36 | 139 | 520 | 18 | 29 | 1 | 8 | 13 | 921 | |

| Referral hospitals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CCBRT | 1 0.2 |

3 0.5 |

3 0.5 |

4 0.6. |

5 0.8 |

0 0 |

4 0.6 |

8 1.2 |

8 1.2 |

8 1.2 |

4 0.6 |

7 1.1 |

6 0.9 |

20 3.1 |

34 5.2 |

7 1.1 |

486 74 |

0 0 |

24 3.7 |

1 0.1 |

8 1.2 |

13 1.9 |

654 100 |

|

| Muhumbili | 0 0.0 |

1 2.3 |

0 0 |

0 0. |

0 0 |

0 0 |

1 2.3 |

2 4.5 |

1 2.3 |

10 2.3 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

2 4.5 |

0 0 |

34 77 |

0 0 |

2 4.5 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

44 100 |

|

| KCMC | 50 22.4 |

0 0. |

3 1.3 |

1 0.4 |

4 1.8 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

1 0.4 |

1 0.4 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

2 0.9 |

8 3.6 |

0 0 |

132 59 |

0 0 |

18 8.1 |

3 1.3 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

223 100 |

|

| Total | 51 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 28 | 36 | 139 | 520 | 18 | 29 | 1 | 8 | 13 | 921 | |

CCBRT, Muhumbili, and KCMC data for patients were collected from January 2006 to December 2008. There were 76 patients operated at Muhumbili but data on region of residence was available on only 44.

CCBRT Comprehensive Community Based Rehabilitation in Tanzania; HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus; KCMC Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center; OSSN ocular surface squamous neoplasia.

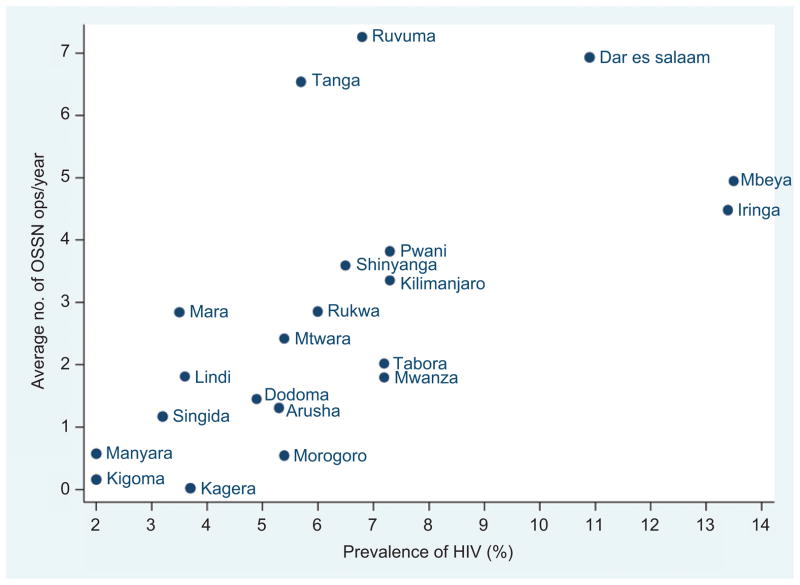

The number of operated cases of suspected OSSN by region, both at referral hospitals and regional hospitals, is shown in Table 3. Figure 1 shows the relationship between estimated incidence and HIV prevalence (omitting the four regions from which no regional data were available), for which the Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.53 (P = 0.03).

TABLE 3.

Operated cases of suspected OSSN in Tanzania by regions

| Region | Average operated cases per year in regions(RECs) | Average operated cases per year at referral hospitals | Total operated cases per year | Population in region | Operated OSSN per year per 100,000 people | HIV prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arusha | 0 | 17 | 17 | 1,292,973 | 1.3 | 5.3 |

| Dar es salaam | 0 | 173 | 173 | 2,497,940 | 6.9 | 10.9 |

| Dodoma | 22 | 3 | 25 | 1,698,996 | 1.4 | 4.9 |

| Iringa | 64 | 3 | 67 | 1,495,333 | 4.5 | 13.4 |

| Kagera | - | 0 | 0 | 2,033,888 | 0 | 3.7 |

| Kigoma | - | 3 | 3 | 1,679,109 | 0.2 | 2.0 |

| Kilimanjaro | - | 46 | 46 | 1,381,149 | 3.3 | 7.3 |

| Lindi | 12 | 2 | 14 | 791,306 | 1.8 | 3.6 |

| Manyara | - | 6 | 6 | 1,040,461 | 0.6 | 2.0 |

| Mara | 39 | 2 | 41 | 1,368,602 | 2.8 | 3.5 |

| Mbeya | 99 | 3 | 102 | 2,070,046 | 4.9 | 13.5 |

| Morogoro | - | 10 | 10 | 1,759,809 | 0.5 | 5.4 |

| Mtwara | 26 | 1 | 27 | 1,128,523 | 2.4 | 5.4 |

| Mwanza | 51 | 1 | 52 | 2,942,148 | 1.8 | 7.2 |

| Pwani | 22 | 12 | 34 | 889,154 | 3.8 | 7.3 |

| Rukwa | 31 | 2 | 33 | 1,141,743 | 2.9 | 6.0 |

| Ruvuma | 81 | 0.00 | 81 | 1,117,166 | 7.2 | 6.8 |

| Shinyanga | 98 | 3 | 101 | 2,805,580 | 3.6 | 6.5 |

| Singida | 11 | 2 | 13 | 1,090,758 | 1.2 | 3.2 |

| Tabora | 31 | 34 | 35 | 1,717,908 | 2.0 | 7.2 |

| Tanga | 98 | 9 | 107 | 1,642,015 | 6.5 | 5.7 |

| Total | 683 | 302 | 985 | 33,584,607 | 2.9 | 7.0 |

HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; OSSN: ocular surface squamous neoplasia; REC: Regional Eye Coordinator.

FIGURE 1.

Annual average number of operations/year/100,000 population for suspected OSSN compared to Human Immunodeficiency Virus prevalence in each region.

DISCUSSION

The epidemiology and management of OSSN in Tanzania has not previously been described. The annual incidence estimate here is based on the assumption that most people with OSSN eventually present for surgery and probably do so within about a year of the development of the lesion. Since OSSN is a progressive condition that only can be treated by surgery in Tanzania, this is a reasonable assumption. There are a limited number of places where patients can have the surgery done and these are at the referral hospitals or by doctors or paramedical eye workers in the regions. All of these were included in the training and all responded with follow up except as noted from four regions. If any cases of OSSN were not captured, this would lead to an underestimation. In calculating incidence from regional hospitals only cases actually operated on were included to avoid double counting those that were referred for surgery to referral hospitals.

Another assumption, for the regions where we had data for less than a full year, is that the monthly rate does not vary. This is probably a reasonable assumption since the condition is not seasonal.

A major weakness of this study is the fact that we can only calculate the incidence of suspected OSSN; we do not have histologic confirmation of cases. This is rarely available, even at referral hospitals, except in special studies or in unusual cases. We hope some errors in diagnosis were minimized by the educational seminar provided for participant eye care workers. McKelvie in 2002 reported that preoperative clinical diagnosis in lesions < 10mm, OSSN was correctly diagnosed in 92% of cases while for lesions >10mm, it was correctly diagnosed in 78% of cases.10 Our experience in an ongoing study at KCMC is that approximately 75% of suspected OSSN in an eye clinic turn out to be OSSN on histologic examination (authors’ data). In this study, if we assume that the diagnosis was correct in 75% of the cases, the estimated incidence becomes 2.2 instead of 2.9. This finding agrees closely with the incidence of 2.1 per 100,000 persons reported by Parkin 8 from neighboring Uganda between 1995 and 1997. These incidence rates are dramatically higher than that reported in 1997 in the United States where the incidence was 0.03 cases per 100,000 persons.11

Although the available data on regional prevalence of HIV infection likely contains errors, the significant correlation between these estimates and the estimated regional incidence of OSSN is expected in a condition like OSSN that is so closely associated with HIV and supports the validity of our incidence estimate. In keeping with the association with HIV infection in Africa, around 90% of cases in Tanzania are under 50 years; this is in sharp contrast with reports from the industrialized countries where most patients with OSSN are elderly and male.10–13 The higher prevalence in females is a new finding, which may reflect the fact that HIV infection is slightly more prevalent (7.7%) in females than in males (6.8%) in Tanzania.9 Alternatively, males might be more inclined to neglect the condition and die with it untreated or perhaps there really is a greater risk for females to develop OSSN among the HIV infected.

As far as management of this condition in Tanzania, it is interesting to find that 623/1544 (40%) of operated suspected OSSN are managed outside the referral hospitals. At the hospitals in Dar es Salaam, 582/698 (83%) of patients were from Dar es Salaam or nearby Pwani and Morogoro regions. At KCMC, 200/223 (90%) of patients were from Kilimanjaro or nearby Arusha and Manyara. This suggests that patients do not travel far for management of this condition. This is likely to be the case for many years, due to the difficulty of accessing more specialist referral centers. It is an argument for better training of the eye health workers at these centers. Many, for example, were not even aware that OSSN was associated with HIV infection before the training.

Given that OSSN is so commonly associated with HIV infection, it is a great concern that HIV testing is so often not performed in the patients. It is possible that some patients already know their status and thus are not re-tested, but our experience is that OSSN in the eye clinic at KCMC is often the first indication that someone has HIV infection. Testing rates are high at KCMC because there has been a program in place in the eye clinic to ensure testing and access to anti retroviral drugs. As the availability of anti retroviral drugs increases, it is hoped that fewer OSSN will occur in sub-Saharan Africa. However, for the time being, attention to and better management of these patients is needed.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Muhumbili National Hospital and CCBRT for permission to study their files.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The project was supported by Grant Number D43TW006732 from the Fogarty International Center through Duke University. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Fogarty International Center or the National Institute of Health.

References

- 1.Ateenyi-Agaba C. Conjunctival squamous-cell carcinoma associated with HIV infection in Kampala, Uganda. Lancet. 1995;345(8951):695–696. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90870-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waddell KM, Lewallen S, Lucas SB, et al. Carcinoma of the conjunctiva and HIV infection in Uganda and Malawi. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80(6):503–508. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.6.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orem J, Otieno MW, Remick SC. AIDS-associated cancer in developing nations. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16(5):468–476. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200409000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kestelyn P, Stevens AM, Ndayambaje A, et al. HIV and conjunctival malignancies. Lancet. 1990;336(8706):51–52. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91562-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poole TR. Conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in Tanzania. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83(2):177–179. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewallen S. HIV/AIDS: what is the impact on prevention of blindness programs? Community Eye Health. 2003;16(47):33–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chokunonga E, Levy LM, Bassett MT, et al. AIDS and cancer in Africa: the evolving epidemic in Zimbabwe. AIDS. 1999;(18):2583–2588. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199912240-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parkin DM, Wabinga H, Nambooze S, Wabwire-Mangen F. AIDS-related cancers in Africa: maturation of the epidemic in Uganda. AIDS. 1999;(18):2563–2570. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199912240-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanzania Commission for AIDS (TACAIDS) NBoSN, and ORC Macro. Tanzania HIV/AIDS Indicator Survey 2003–2004. Calverton, Maryland, USA: TACAIDS, NBS, and ORC Macro; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKelvie PA, Daniell M, McNab A, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: a series of 26 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;(2):168–173. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun EC, Fears TR, Goedert JJ. Epidemiology of squamous cell conjunctival cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;(2):73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cervantes G, Rodriguez AA, Jr, Leal AG. Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: clinicopathological features in 287 cases. Can J Ophthalmol. 2002;37(1):14–19. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(02)80093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee GA, Hirst LW. Incidence of ocular surface epithelial dysplasia in metropolitan Brisbane. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:525–257. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080160103042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]