Abstract

Pavlovian conditioning models have led to cue-exposure treatments for drug abuse. However, conditioned responding to drug stimuli can return (be renewed) following treatment. Animal research and a previous study of social drinkers indicated that extinction is highly context dependent but that renewal could be reduced by the inclusion of a cue from the extinction context. This study extends this research to a clinical sample. Alcohol-dependent outpatients (N = 143) completed an extinction trial to reduce craving and salivation responses to alcohol cues. They were then randomized to renewal tests in either the same context as extinction, a different context, the different context containing an extinction cue, or the different context with cue plus a manipulation to increase the salience of the cue. Contrary to predictions, the different context did not produce the expected renewal effect. Although the generalization of extinction effects beyond the cue-exposure context is a positive clinical finding, it is inconsistent with basic research findings on the context dependence of extinction. Possible explanations for this inconsistency are discussed.

Keywords: classical conditioning, context, extinction, alcohol, craving

The aim of cue-exposure treatment (CET) for alcohol dependence is to decrease motivation for alcohol consumption by exposing individuals to alcohol-related stimuli while preventing alcohol consumption to produce extinction of conditioned alcohol responses, including craving (e.g., Childress, McLellan, & O'Brien, 1986). Studies using CET have shown a decrease in desire for alcohol, higher incidence of abstinence, higher percentage of abstinent days during posttreatment follow-up (e.g., Monti, Rohsenow, Rubonis, Niaura, Sirota, Colby, & Abrams, 1993; Monti, Rohsenow, Rubonis, Niaura, Sirota, Colby, et al., 1993), and increased latency to return to heavy drinking (Drummond & Glautier, 1994). In a problem-drinking population, CET produced superior outcomes in terms of drinking frequency and consumption per drinking episode compared with standard cognitive behavioral therapy (Sitharthan, Sitharthan, Hough, & Kavanagh, 1997). As a result of these promising results, CET has been recommended as an adjunct to comprehensive alcohol treatment programs (Rohsenow, Monti, & Abrams, 1995); however, no one definitive approach for conducting CET has yet been recommended. Nevertheless, findings from recent research on Pavlovian extinction suggest that several modifications could be made to the way CET is conducted. Such changes have direct implications for enhancing the generalization of CET effects and are reviewed below.

CET studies typically involve three phases: pretest, extinction (treatment), and posttest. In alcohol CET studies conducted to date, all three phases have been conducted in the same context. However, recent animal laboratory research has demonstrated that context plays an important role in determining the response to a conditioned stimulus (CS) following extinction (e.g., Bouton, 1993). For example, several studies investigating contextual control of extinction performance have demonstrated that responding to a CS can be renewed if the extinguished CS is tested in a context that differs from the extinction (i.e., treatment) context (see Bouton & Nelson, 1998, for a review). This research indicates that extinction does not erase conditioned associations but, instead, creates additional inhibitory associations that are highly context dependent (but see McSweeney & Swindell, 2002, for an alternative perspective). The clinical implication is that when an individual is exposed to alcohol cues in his or her natural environment following extinction of those same cues in a treatment context, a return, or renewal, of conditioned responding is likely. Further, this renewal of responding may be an important factor that increases relapse rates (Gunther, Denniston, & Miller, 1998). The renewal effect has been shown in animal studies as well as in human anxiety studies with people who have spider phobia (e.g., Mystkowski, Craske, & Echiverri, 2002; Rodriguez, Craske, Mineka, & Hladek, 1999) and in one study with heavy social drinkers (Collins & Brandon, 2002).

The animal literature has extended research on context effects by demonstrating strategies that minimize extinction instability. For example, in an appetitive-conditioning paradigm, Brooks and Bouton (1994) demonstrated attenuation of renewal by adding a stimulus from the previous extinction context into the renewal-test context. During renewal testing, the presence of this extinction context memory-retrieval cue (E-cue) produced less renewal than did testing without the E-cue, testing with a novel cue presented during the renewal test, or testing with a cue presented during conditioning involving the CS. In the only human study conducted to date using heavy social drinkers, the presence of an E-cue during the renewal test significantly reduced the magnitude of renewal (Collins & Brandon, 2002).

Our primary aim in the present study was to test if Collins and Brandon's (2002) findings of context and E-cue effects on renewal in social drinkers would generalize to a clinical sample of alcohol-dependent outpatients. We hypothesized that following extinction, between-groups differences in cue reactivity (CR) that could be attributed to context change and the presence of the E-cue would emerge across conditions on the renewal test (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Experimental Design and Predictions of Performance at Renewal Test

| Session 2 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Session 1 (BL measures) | CR pretest | Extinction | CR posttest | Session 3 (Renewal test) | Prediction |

| SC | A | A | A | A | A | Maintained extinction |

| DC | B | A | A | A | B | Renewal of reactivity |

| DC + E-cue | B | A | A | A | B | Attenuated renewal |

| DC + S E-cue | B | A | A | A | B | Attenuated renewal |

Note. The rooms used for Context A and Context B were counterbalanced within conditions. BL = baseline questionnaire assessment; CR = cue-reactivity assessment; SC = same context; DC = different context; DC + E-cue = different context plus extinction cue; DC + S E-cue = different context plus extinction cue with saliency manipulation.

Method

Participants

Participants were 143 alcohol-dependent men and women, recruited from one of three publicly funded outpatient substance abuse clinics in Buffalo, New York. Inclusion criteria were at least 1 heavy drinking day in the past month, no medications that could interfere with salivation (e.g., anticraving medications, anticholinergics, cholinergic agonists), and validation as an alcohol-cue responder.1 Individuals who met these criteria were randomly assigned to conditions and scheduled for all three sessions to be held on consecutive days.

Independent Variables

Context

Two testing rooms represented two unique contexts and were counterbalanced within conditions. The rooms differed in dimension, decor, lighting, furniture, and location (second vs. fourth floor).

E-cue

The E-cue in this study was similar to that used by Collins and Brandon (2002): a novelty pencil with a textured grip and weighted eraser, with a neon orange plastic clipboard. Participants used these instruments to complete their craving ratings. The E-cue was present in the extinction context (Session 2) across all conditions and during the renewal test for the different context plus E-cue (DC + E-cue) group and the different context plus E-cue with saliency manipulation (DC + S E-cue) group (see Table 1).

Saliency manipulation (DC + S E-cue group only)

Saliency refers to the observation that some stimuli enter into associations more readily than do others (Rescorla, 1988). Important to the present study is the relative saliency of the E-cue versus that of the alcohol-beverage cues. If the E-cue is not sufficiently salient it may not be noticed, and its relatedness to the assumed behavior may be overshadowed by the alcohol cues. Therefore, we directly manipulated the saliency of the E-cue for participants in the DC + S E-cue group by increasing their attention to the cues.

To evaluate the effect of stimulus saliency on renewal of responding during the posttest, we manipulated the saliency of the E-cue for the DC + S E-cue group by instructing participants to associate (integrate) the E-cue with the context. That is, the participant was instructed to generate an image in which the novelty pen and clipboard were visualized as being conjoined with or directly connected to a particular feature of the extinction context (e.g., Eich, 1985). For example, the participant might say, “I imagine the pen and clipboard hanging on the wall above the table.” These instructions were administered after the participant completed the extinction phase so that the integrated image would be formed while the participant was experiencing a low level of craving (i.e., extinction effect).

Dependent Measures

Craving self-report

The primary measure of reactivity was self-reported craving, obtained using a 3-item, 11-point Likert-type scale: “I do want to drink now,” “I crave a drink right now,” and “I have a desire for a drink right now.” These items were derived from previous research investigating the assessment of craving in smokers (Kozlowski, Pillitteri, Sweeney, Whitfield, & Graham, 1996) and also from a reliable scale (coefficient α = .95) for the assessment of alcohol craving in a clinical sample of alcoholics (Klein, Stasiewicz, Koutsky, Bradizza, & Coffey, in press).

Salivation

Our secondary measure of CR was the salivary response. Saliva was measured by weighing three cotton dental rolls that participants had placed in their mouths during each CR trial (one under the tongue and one on either side of the mouth). This procedure was used effectively in an earlier study (Collins & Brandon, 2002).

Procedure

At the beginning of each session, participants were administered a breath test. If a participant's blood alcohol level was >.00, the session was rescheduled. All sessions took place between noon and early evening.

Session 1

On arrival at his or her session, each participant received a detailed introduction to the study and completed a consent form in the interview room, which was either Context A or Context B, depending on the participant's experimental condition. Session 1 was conducted in the room in which the renewal test (Session 3) was to be conducted. Preexposure potentially minimizes post hoc explanations of reactivity during the renewal test that may be attributable to the novelty of the room. After the introduction to the study, participants were told that this session would involve completing questionnaires about their alcohol-related behaviors. Alcohol dependence was assessed by one of two research technicians trained in the administration of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule-IV (Robins, Helzer, Cottler, & Goldring, 1997).

Session 2

The CR pretest, extinction phase, and CR posttest were conducted during this session. On arrival, each participant was escorted to either Context A or Context B, depending on his or her experimental condition. Baseline measures of craving to drink water and craving to drink alcohol were assessed. Next, the participant placed three cotton dental rolls in his or her mouth, and the experimenter revealed the beverage cues, which included a glass of the participant's most frequently consumed alcoholic beverage (e.g., Pabst Blue Ribbon beer) and the commercial container for the alcoholic beverage (e.g., 12-oz can). The experimenter instructed the participant not to drink the alcoholic beverage and then took a seat slightly behind and out of sight of the participant, thus minimizing potential distractions and enabling the participant to focus attention on the beverage cues. The participant was then prompted to lift the glass and sniff it for 5 s. Sniffing occurred six times during the 3-min alcohol trial. Following the alcohol trial, the participant completed the three-item alcohol-craving scale.

For all four groups, the extinction phase involved in vivo exposure to the participants' usual alcoholic beverages. Participants were asked to focus on the beverage and aspects of the beverage that would strengthen their cravings for alcohol. For example, participants were encouraged to pour the beverage into a glass and pick up the glass periodically. At 3-min intervals, the experimenter prompted participants to report their levels of craving on one item from the craving scale (i.e., “I crave a drink right now.”). The focus on the beverage was terminated when the participant's self-report of craving was 2 on the 10-point scale for two consecutive ratings. This criterion was used successfully in a previous study investigating within-session extinction to alcohol cues (Stasiewicz et al., 1997). The maximum amount of exposure time was set at 60 min.2 If an individual failed to reach the extinction criterion within this time period, he or she was instructed to stop focusing on the alcohol cues. After extinction, the beverage was removed from the room, and the participant completed the 3-item craving measure. For the DC + S E-cue group only, the saliency manipulation then occurred.

Following the extinction phase, a CR posttest was conducted. The CR posttest procedures are identical to the CR pretest procedures described above.

Session 3

The renewal test was conducted during this session. Participants returned 1 day after the extinction session to their Session 1 contexts for the renewal test (see Table 1). The E-cue was present during the renewal test for only the DC + E-cue and DC + S E-cue groups. The procedure for the renewal test was the same as the procedure for the CR pre- and posttests.

Results

Participant Characteristics and Group Equivalence

The mean age of the participants was 39.28 years (SD = 9.93). The sample was primarily African American (62%) and male (56%). All participants met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for alcohol dependence as determined by the Diagnostic Interview Schedule-IV. Alcohol dependence severity was moderate, on the basis of scores on the Alcohol Dependence Scale (Skinner & Allen, 1982; M = 18.86, SD = 9.24). On the Timeline Follow-back (Sobell & Sobell, 1992), participants reported consuming an average of 12.70 (SD = 8.97) drinks per drinking day during the 90-day period prior to study entry. No significant differences emerged across conditions on the major demographic and alcohol-consumption variables.

Reactivity Equivalence Across Groups Through the Extinction Phase

We conducted analyses to test for the equivalence of groups from baseline through extinction. There were no significant differences in mean craving ratings or saliva weights across conditions at baseline. After establishing equivalence of groups at baseline, we conducted 2 (Time) × 4 (Condition) mixed analyses of variance to test whether saliva weight and craving means increased from baseline to pretest. We found the predicted increase in craving ratings from baseline to pretest, F(1, 139) = 227.67, p < .0001, and no main effect for condition or Condition × Time interactions. Likewise, we found only the expected increase in saliva weight from baseline to pretest, F(1, 106) = 97.90, p < .0001. These results suggest equivalent increases in saliva and craving reactivity across groups from baseline to the pretest, as expected.

To test the equivalence of extinction across groups, we conducted 2 × 4 mixed analyses of variance across conditions between the pretest and posttest on both dependent measures. As expected, craving scores decreased over time, F(1, 139) = 20.54, p < .0001, without a main effect for condition or an interaction. Therefore, the craving results indicate that both CR and extinction occurred and that the four conditions produced similar patterns of reactivity and extinction. In contrast, we found no significant main effects or interaction for saliva weight, indicating that extinction of this response did not occur. Because extinction is a precondition of renewal, the analysis of context effects focuses on the craving data only.

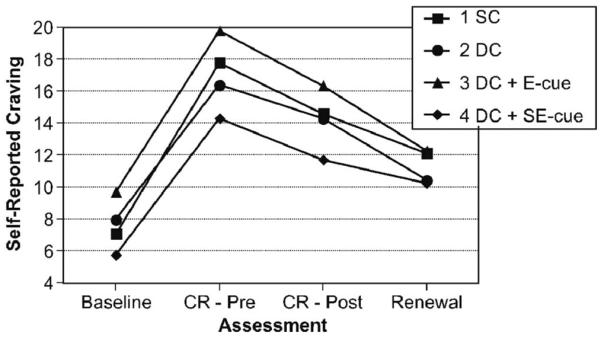

Context Effects

We hypothesized that craving differences would emerge across conditions between the alcohol-cue posttest administered at the end of Session 2 and the renewal test administered at Session 3. We specifically predicted that the lowest craving magnitude would be found in the same-context group, the greatest would be found in the different-context group, and an intermediate level of craving would be found in the DC + E-cue group and the DC + S E-cue group, with the latter possibly showing lower craving than the former. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a 2 × 4 mixed analysis of variance across conditions between the posttest and renewal test with craving responding as the dependent variable. The analysis revealed a significant time effect, F(1, 139) = 17.28, p < .0001, but no main effect for condition and no Condition × Time interaction. Therefore, the analysis did not support the prediction of differential craving responding due to a context effect, E-cue effect, or saliency manipulation. Rather, as seen in Figure 1, the data show that craving responding continued to decrease between the posttest and renewal test across all four conditions.

Figure 1.

Mean self-report of urge ratings from baseline through renewal test for the same-context (SC), different-context (DC), DC plus extinction-cue (DC + E-cue), and DC plus salient E-cue (DC + SE-cue) groups. CR - Pre = cue reactivity pretest; CR - Post = cue reactivity posttest.

Discussion

This study provided a test of the role of extinction context in alcohol-cue exposure in a sample of alcohol-dependent outpatients. The results from this study are inconsistent with those of other animal and human studies that have demonstrated a renewal effect. There are several potential explanations for the failure to produce the expected renewal effect.

First, the two contexts may not have been sufficiently discriminable by the participants. Although the two rooms were appreciably different, they were located in the same building within the same campus. Thus, it is possible that the campus or building itself may have represented the context of extinction for these participants (see Bouton, 2002). Second, too little time may have elapsed between the extinction trial and the renewal test (M = 1.1 days, SD = 0.37). Given that the passage of time may also be construed as contextual change (Bouton, 2002), a longer interval may have created a more clinically relevant renewal condition. Future studies might consider extending the interval between the extinction phase and the renewal test. Third, demand effects and social desirability may have influenced the reporting of low craving during the renewal test. Participants in a treatment program may be disinclined to report posttreatment cravings. It may be important to emphasize to participants that the experience of craving is normal and does not reflect poorly upon them. For example, participants may have learned during the extinction phase that the session ended when they reported low craving for two consecutive rating periods. Thus, they may have been motivated to report low craving during the Session 3 renewal test. Fourth, the presence of the experimenter in the room may have served as an unintentional E-cue because the same experimenter was present during the extinction phase and the renewal test. Although the experimenter sat behind and out of sight of the participant, it is possible that the experimenter served as a salient contextual cue, which attenuated renewal. Future research might vary the characteristics of the experimenter between the extinction and renewal tests (see Rodriguez et al., 1999). Fifth, there may not have been sufficient extinction. Only one 60-min extinction session was conducted, and the average duration of exposure was 40.36 min (SD = 23.89). Moreover, only 69% of participants reached the extinction criterion. Greater extinction might have allowed for the emergence of greater renewal differences across conditions.

Finally, the form of renewal employed in the present study may also have contributed to the failure to observe a renewal effect. The most widely studied form of renewal is termed ABA renewal (see Bouton & Nelson, 1998), when the acquisition and renewal test contexts are the same and the extinction context is different. In contrast, this study manipulated the treatment and posttreatment contexts in an ABC design. Overall, animal research indicates that ABA renewal tends to be stronger than ABC. However, ABA renewal testing is not realistic in studies using a human clinical population, because the acquisition is not under the control of the experimenter, and it has likely occurred over an appreciable period of time in multiple contexts. This is often a limitation of human-conditioning studies, as participants bring many years of unspecified and unknowable experience to the situation.

The findings from this study most clearly contrast with those of Collins and Brandon (2002), who found extinction effects for both craving and salivation, a context-based renewal effect, and attenuation of renewal with the use of an E-cue. The major differences between the two studies are that we used a clinical sample of alcoholic patients, whereas Collins and Brandon studied heavy-drinking college students; and we administered the renewal test a day after the last extinction trial, whereas Collins and Brandon administered the renewal test only 25 min after extinction. We expected that the greater interval between extinction and renewal testing would produce larger renewal effects, rather than smaller. Thus, the difference in samples is the most likely source of the outcome differences.

This study represents the third human population examined for postextinction contextual differences in renewal responding, after people with spider phobia (e.g., Mystkowski et al., 2002) and heavy social drinkers (Collins & Brandon, 2002). Unlike prior researchers, we failed to find the hypothesized context effect. The methodological issues discussed above illustrate the difficulty in translating basic animal-learning research for use with a human clinical population. Nevertheless, the clinical potential of such translational research remains high, and studies such as this one may help researchers triangulate upon the necessary and sufficient procedures for demonstrating effects first in the human laboratory and ultimately in the clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant AA12033 awarded to Paul R. Stasiewicz. We thank Ralph Miller and Peter Monti for their roles as consultants on this project. We thank Joseph Saeva, Robert Whitney, and the staff of the Erie County Medical Center Downtown Clinic. Finally, we thank Kellie Smith-Hoerter, Alexis Hazard, Dennis Dickman, and the staff of the Clinical Research Center for their efforts on the project.

Footnotes

Responder status was determined on the basis of any increase in self-reported craving from the water trial to the alcohol trial. This definition of responder status has been used in previous alcohol-cue reactivity studies with alcoholics, and the percentage of nonresponders in the current study is consistent with that in previous studies (n = 51, 21%; Rohsenow et al., 1992; Monti, Rohsenow, Rubonis, Niaura, Sirota, Colby, & Abrams, 1993).

Sixty minutes was the maximum time allotted for the extinction phase. However, exposure to the alcohol cues was terminated prior to 60 min if the participant met the extinction criterion established for this study. Thus, exposure durations varied, with some participants receiving less than 60 min of exposure.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed Author; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context, time, and memory retrieval in the interference paradigms of Pavlovian learning. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:80–99. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Context, ambiguity, and unlearning: Sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:976–986. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Nelson JB. The role of context in classical conditioning: Some implications for cognitive behavior therapy. In: O'Donohue W, editor. Learning and behavior therapy. Allyn & Bacon; Boston: 1998. pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DC, Bouton ME. A retrieval cue for extinction attenuates response recovery (renewal) caused by a return to the conditioning context. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1994;20:366–379. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.19.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress AR, McLellan AT, O'Brien CP. Abstinent opiate abusers exhibit conditioned craving, conditioned withdrawal and reductions in both through extinction. British Journal of Addiction. 1986;81:655–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins BN, Brandon TH. Effects of extinction context and retrieval cues on reactivity among nonalcoholic drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:390–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond DC, Glautier S. A controlled trial of cue exposure treatment in alcohol dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:809–817. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.4.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eich E. Context, memory, and integrated item/context imagery. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1985;11:764–770. [Google Scholar]

- Gunther LM, Denniston JC, Miller RR. Conducting exposure treatment in multiple contexts can prevent relapse. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:75–91. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A, Stasiewicz PR, Koutsky JR, Bradizza CM, Coffey SF. A psychometric evaluation of the Approach and Avoidance of Alcohol Questionnaire (AAAQ) in alcohol dependent outpatients. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. doi: 10.1007/s10862-019-09740-3. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Pillitteri JL, Sweeney CT, Whitfield KE, Graham JW. Asking questions about urges and cravings for cigarettes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:248–260. [Google Scholar]

- McSweeney FK, Swindell S. Common processes may contribute to extinction and habituation. The Journal of General Psychology. 2002;129:364–400. doi: 10.1080/00221300209602103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Rubonis AV, Niaura RS, Sirota AD, Colby SM, Abrams DB. Alcohol cue reactivity: Effects of detoxification and extended exposure. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:235–245. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Rubonis AV, Niaura RS, Sirota AD, Colby SM, et al. Cue exposure with coping skills treatment for male alcoholics: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:1011–1018. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mystkowski JL, Craske MG, Echiverri AM. Treatment context and return of fear in spider phobia. Behavior Therapy. 2002;33:399–416. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Pavlovian conditioning: It's not what you think it is. American Psychologist. 1988;43:151–160. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.43.3.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Helzer J, Cottler L, Goldring E. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule. Version 4 Washington University School of Medicine; St. Louis, MO: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez BI, Craske MG, Mineka S, Hladek D. Context-specificity of relapse: Effects of therapist and environmental context on return of fear. Behavior Research Therapy. 1999;37:845–862. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Abrams DB. Cue exposure treatment in alcohol dependence. In: Drummond DC, Tiffany ST, Glautier S, Remington B, editors. Addictive behaviour: Cue exposure theory and practice. Wiley; New York: 1995. pp. 169–196. [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Abrams DB, Rubonis AV, Niaura RS, Sirota AD, Colby SM. Cue elicited urge to drink and salivation in alcoholics: Relationship to individual differences. Advances in Behavior Research and Therapy. 1992;14:195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Sitharthan T, Sitharthan G, Hough MJ, Kavanagh DJ. Cue exposure in moderation drinking: A comparison with cognitive–behavior therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:878–882. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Allen BA. Alcohol dependence syndrome: Measurement and validation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1982;91:199–209. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.91.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Sobell M. Timeline Follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen JA, Litten RZ, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stasiewicz PR, Gulliver SB, Bradizza CM, Torrisi R, Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM. Exposure to negative affect and reactivity to alcohol cues during alcohol cue exposure. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:1143–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]