Abstract

BACKGROUND

Duodenal-jejunal bypass (DJB) has been shown to reverse type 2 diabetes (T2DM) in Goto-Kakazaki (GK) rats, a rodent model of non-obese T2DM. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is a hallmark decrement in T2DM. The aim of the current work was to investigate the effects of DJB on skeletal muscle insulin signal transduction and glucose disposal. It was hypothesized that DJB would increase skeletal muscle insulin signal transduction and glucose disposal in GK rats.

METHODS

DJB was performed in GK rats. Sham operations were performed in GK and non-diabetic Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats. At two weeks post-DJB, oral glucose tolerance (OGTT) was measured. At three weeks post-DJB, insulin-induced signal transduction and glucose disposal were measured in skeletal muscle.

RESULTS

In GK rats and compared to Sham operation, DJB did not: 1) improve fasting glucose or insulin; 2) improve OGTT; or 3) increase skeletal muscle insulin signal transduction or glucose disposal. Interestingly, skeletal muscle glucose disposal was similar between WKY-Sham, GK-Sham, and GK-DJB.

CONCLUSIONS

Bypassing of the proximal small intestine does not increase skeletal muscle glucose disposal. The lack of skeletal muscle insulin resistance in GK rats questions whether this animal model is adequate to investigate the etiology and treatments for T2DM. Additionally, bypassing of the foregut may lead to different findings in other animal models of T2DM as well as in T2DM patients.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes, duodenal-jejunal bypass, skeletal muscle glucose disposal

INTRODUCTION

According to the American Diabetes Association, 20.8 million Americans, or 7% of the population, currently suffer from type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). This number is estimated to climb to as high as 39 million by 2050 (18). In addition to being the fifth leading cause of death, diabetes also increases the risk and complications of several diseases including heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, blindness, kidney disease, nervous system disorders, amputations, dental disease, and complications with pregnancy. The cost of diabetes in the United States was estimated to be $149 billion in 2005 and is projected to be as high as $192 billion by 2020 (18). In 2002, health care spending for people with diabetes was more than double what spending would have been without diabetes (1). Type 2 diabetes is a prevalent, expensive, and deadly disease of which identifying the mechanism(s) responsible for diabetes and effective treatments remain to be discerned.

Could the proximal small intestine contribute to diabetes and insulin resistance? Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) consists of surgical reduction in the size of the stomach and bypassing of a portion of the proximal small intestine (foregut). While used to promote weight loss in extremely obese patients, RYGB is an effective treatment for type 2 diabetes. In 1987 our group reported that 86 of 88 patients (97.7%) with type 2 diabetes became euglycemic (without medications) within 4 months following RYGB (24). These findings were supported in a meta-analysis where RYGB resolved diabetes in 77% of patients (3).

The potential mechanisms responsible for this reversal of type 2 diabetes following RYGB include: 1) weight reduction, 2) food restriction, 3) bypassing of the proximal small intestine; and 4) expedited delivery of food to the distal small intestine. In a case report on two patients by Cohen et al., bypassing of the duodenum and proximal jejunum bypass (DJB) reduced fasting glucose on average from 163 mg/dL to 99 mg/dL and 88 mg/dL at 3 and 9 mo post-DJB (without medications), respectively and without weight loss (1 Wk BMI: 28.0 kg/m2 vs. 28.3 and 28.0 kg/m2 at 3 and 9 mo post-DJB, respectively) (7). DJB reverses diabetes and increases insulin sensitivity in Goto-Kakazaki (GK) rats, a model of non-obese type 2 diabetes (27, 28). These findings suggest that bypassing of the foregut alone holds the potential to improve type 2 diabetes.

Type 2 diabetes is defined as elevated blood glucose that results from progressive insulin resistance in insulin sensitive tissues (skeletal muscle, liver, and fat) that cannot be compensated for with increased pancreatic insulin secretion. In the fasted condition, elevated blood glucose in moderate to severe T2DM is attributed to increased hepatic glucose production (10). In the non-fasted state, 80-90% of insulin-induced glucose disposal occurs in skeletal muscle (12). Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is a hallmark decrement in T2DM in humans (8, 23). It was hypothesized that DJB would improve skeletal muscle insulin-induced signaling and glucose disposal in type 2 diabetic GK rats. Because improvements in whole body insulin sensitivity could be due to improvements in hepatic insulin resistance, we also measured insulin-induced signaling in the liver.

MATERIALS and METHODS

This study was approved by the East Carolina University Animal Care and Use Committee. Ten to 12 wk old male Goto-Kakazaki (GK) and Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats were used (Taconic, Hudson, NY). All rats were kept in a controlled setting at 22°C, on a 12:12 hour light:dark cycle, and were fed standard chow and water ad libitum except where noted below as necessitated by pre- and post-operative care. After one week of acclimatization in the facility, GK rats were randomly assigned to one of two surgical groups: duodenal jejunal bypass (GK-DJB) or sham (GK-Sham). All WKY rats received the sham operation (WKY-Sham).

Pre-Operative Care

At 18 hrs prior to surgery, food was removed to avoid the presence of food substance in the gastrointestinal tract. At 30 min prior to surgery, an intramuscular injection of Ceftriaxone (3rd generation cephalosporin antibiotic) was given prophylactically at a dosage of 0.25 g/kg. Rats were anesthetized using a mixture of 2% isoflurane and 1.5 L O2/minute, titrated as needed for proper levels of anesthesia. Immediately following administration of general anesthesia, the surgical site was shaved and subsequently cleaned using a 2% chlorohexidine solution. Prior to the initial incision, morphine (10 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously. Rats were kept on a water-circulated heating pad throughout the duration of the surgery.

Duodenal-Jejunal Bypass (DJB) and Sham Operations

The DJB surgery was performed as described by Rubino and Marescaux (28). After a mid-line incision, the duodenum was transected just distal to the pylorus and suture closed at its proximal end. The jejunum was transected 10 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz with the distal of the two limbs connected to the pylorus, creating the duodenojejunal anastomosis and the proximal of the two limbs carrying the biliopancreatic juices connected 25 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz (in the context of the original continuity of the small bowel), creating the jejunojejunal anastomosis. All anastomoses were created using 6-0 resorbable suture.

Sham operations were performed by transecting the jejunum 10 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz and by separating the duodenum from the pylorus. Both transections were then reanastomosed, restoring the normal anatomical structure of the gastrointestinal tract.

Post-Operative Care

Immediately following surgery, rats were placed in a warming, oxygenated chamber at approximately 30°C and 1.5 L O2/minute. Animals were then given access to liquid food supplementation (Boost; Nestle Nutrition, Fremont, MI) for two days following surgery and water ad libitum. At 3 hrs following surgery, rats were given a second subcutaneous injection of morphine (10 mg/kg). For 1 and up to 7 days following surgery, animals were given a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesic as needed (Meloxicam, 5 mg/kg). On the 3rd day following surgery, standard chow was introduced to the rats ad libitum and liquid food supplementation was removed. Surgical survivals were: GK-DJB: 14 of 18; GK-Sham: 17 of 22; and WKY-Sham: 6 of 8.

Glucose tolerance tests

At 2 wks following surgery and following an overnight fast, blood was collected from the tail vein to determine baseline glucose and insulin values. A glucose load (2 g/kg) was administered by gavage, and additional blood draws were performed at 30, 60, and 120 min to assess in vivo glucose tolerance. Glucose levels were determined on whole blood samples (OneTouch Ultra glucose analyzer; Lifescan, Milpitas, CA). Remaining blood samples were subsequently centrifuged to separate plasma and stored at −80°C until insulin levels could be determined via a rat/mouse ELISA kit (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO). Area under the curve (AUC) for glucose and insulin was calculated using the individual fasting values as baseline. The homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) was used to assess insulin action using fasting concentrations of glucose and insulin (20).

Insulin Signaling and Western Blot Analysis

In GK rats, DJB has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity (27). Given the inability of glucose to induce an insulin response in GK rats in the current study and the poor inherent insulin responsiveness to glucose recently reported in GK rats (22, 26), we believed that exogenous insulin might unmask DJB-induced changes in muscle and liver. In response to insulin, cellular glucose uptake is promoted by a signaling cascade involving several proteins including Akt.

Approximately 1 wk following the glucose tolerance tests, one subset of rats was used to study insulin-induced signaling in muscle and liver. After an overnight fast, rats were administered an intraperitoneal injection of insulin (0.36 mg/kg) and glucose (1.32 g/kg). Ten minutes following the injection, rats were euthanized and the gastrocnemius muscles and liver were removed and stored at −80°C until further analysis for insulin-induced signaling.

Powdered muscle and liver were homogenized in buffer [50 mM HEPES, 50 mM Na+ pyrophosphate, 100 mM Na+ fluoride, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM Na+ orthovanadate, 1% Triton X-100, and protease and phosphatase (1 and 2) inhibitor cocktails (Sigma, St. Louis, MO)] on ice. After centrifugation for 1 hr at 45,000 g at 4°C, supernatants were extracted (cytosolic portion), protein content was determined using a BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). After addition of sample buffer, samples (50 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE using 7.5 or 10% Tris-HCl gels and then transferred to PVDF for probing with rabbit phospho-Akt and total Akt from (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA). After incubation with primary antibodies, blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, HRP activity was assessed with ECL solution (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and exposed to film. The image was scanned and band densitometry was assessed with Gel Pro Analyzer software, version 4.2 (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). Content of phospho-Akt was calculated from the density of the band of the phospho-Akt divided by the density of total Akt protein (pan-Akt).

Hindlimb Perfusions and Glucose Transport

Approximately 1 wk following glucose tolerance tests, a second subset of animals underwent hindlimb perfusions for the measurement of glucose transport as described previously (13, 14). After a 12 hr fast, rats were anesthesized intraperitoneal with ketamine and xylazine (10 mg/100 g BW). The aorta and vena cave were ligated and a hemicorpus preparation was created. The aorta and vena cave of the hemicorpus were quickly catheterized in succession and a prepared media (4% BSA, 100 mg/dl glucose, 33% washed bovine red blood cells, and Krebs-Henseleit buffer) was perfused at a rate of 18 ml/min and gassed with O2/CO2 (95:5), with chamber temperature maintained at 37°C. Hindlimbs were perfused with no insulin or with a maximal concentration of insulin (100 nM). The first 50 ml of fluid collected from the perfusion prep was discarded while the remaining 100 ml was recirculated. Radioactive label was added to the media at a final concentration of 20 mM sorbitol containing 0.1 μCi of [U-14C]sorbitol and 0.2 μCi of 2-deoxy [3H]glucose. Insulin was also added when appropriate at a concentration of 100 nM. For measures of glucose transport all perfusions were stopped 25 min post administration of radioactive label. Media was sampled for glucose concentration every 5 min throughout the perfusion and 50% liquid dextrose was added when needed to maintain a media glucose concentration of ~100 mg/dl.

Glucose transport was measured in plantaris muscle, which was removed immediately after perfusion, carefully cleaned of connective tissue and fat, and freeze clamped in liquid nitrogen. Powdered tissue (50–100 mg) was added to 0.4 ml of distilled water and then dispersed via heat (40°C) and sonication, followed by the addition of 5 ml of liquid scintillation fluid, as performed previously (14). 3H/14C radioactivity (dpm) and glucose concentrations were analyzed at 5-min intervals and used to determine specific radioactivity. [14C]Sorbitol was utilized to evaluate the amount of glucose in the interstitial space, thus accumulation of intramuscular 0.2 μCi of 2-deoxy [3H]glucose was determined by subtracting extracellular 0.2 μCi of 2-deoxy [3H]glucose (determined from the [14C]sorbitol space) from total muscle 0.2 μCi of 2-deoxy [3H]glucose.

Statistical Treatment

A one-way ANOVA was performed for body weight, body weight changes post-to-pre-surgery, fasting glucose and insulin, AUC for glucose and insulin, and HOMA. A two-way mixed plot factoral ANOVA (surgical group×condition (+/− insulin)) was performed for hindlimb perfusion glucose disposal. Following a significant F ratio, a Fisher’s LSD post-hoc test was used to determine differences between groups. Unpaired Student’s t-tests were performed to differences in insulin signal transduction. Significance was established at P ≤ 0.05 for all statistical sets and data reported are Mean ± SE.

RESULTS

Animals

WKY-Sham rats were heavier prior to surgery than GK-Sham or GK-DJB, but there was no difference between GK-Sham and GK-DJB (WKY-Sham: 463 ± 9 g; GK-Sham: 339 ± 5 g; and GK-DJB: 331 ± 7 g). The change in weight from pre-surgery to 2 wks post-surgery was greater in WKY-Sham than GK-Sham and GK-DJB, but there was no difference in weight gain between GK-Sham and GK-DJB (WKY: 28 ± 4 g; GK-Sham: 1 ± 4 g; and GK-DJB: −9 ± 5 g).

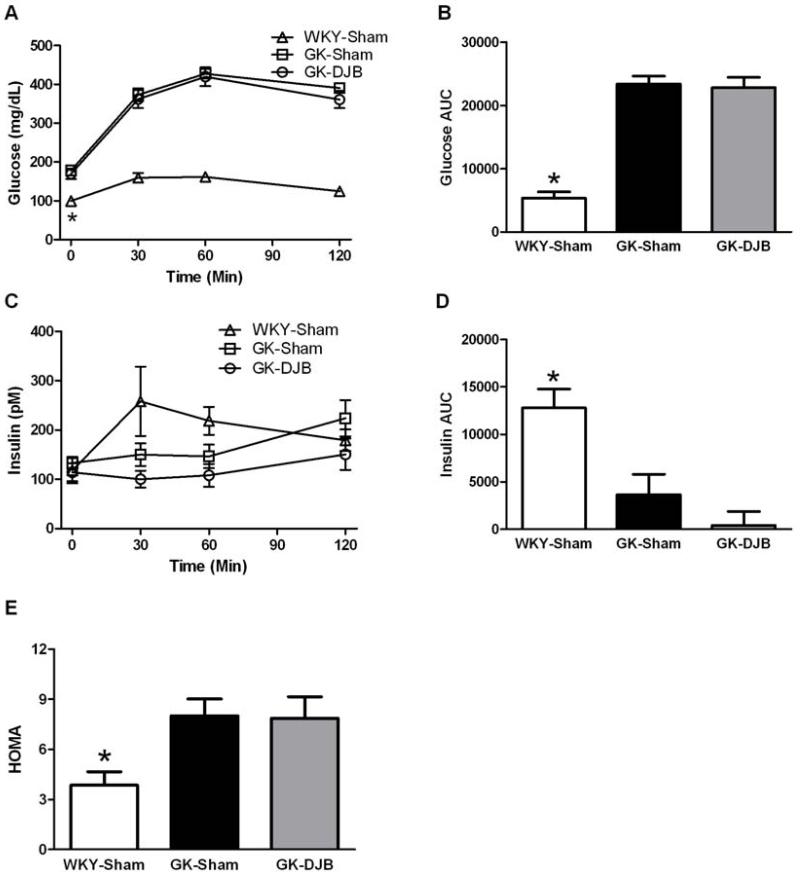

Glucose Tolerance

The glucose and insulin responses to the oral glucose challenge are in Figure 1. Fasting glucose and glucose AUC were lower in WKY-Sham compared to GK-Sham and GK-DJB and there was no difference between surgical groups in the GK rats. There was no difference between groups in fasting insulin and the insulin AUC was greater for WKY-Sham compared to GK-Sham and GK-DJB, but there was no difference between GK groups. WKY-Sham demonstrated a lower HOMA compared to GK-Sham and GK-DJB, but there was no difference between the GK groups.

Figure 1.

Glucose (A, B), insulin (C, D), and HOMA (E) in response to an oral glucose challenge in Sham and DJB operated WKY and GK rats. DJB did not improve the glucose or insulin responses to the glucose challenge or HOMA. * - significantly different than all other groups. Mean ± SE. WKY-Sham: N = 6; GK-Sham: N = 17; and GK-DJB: N =14.

Insulin-induced Akt signaling and skeletal muscle glucose disposal

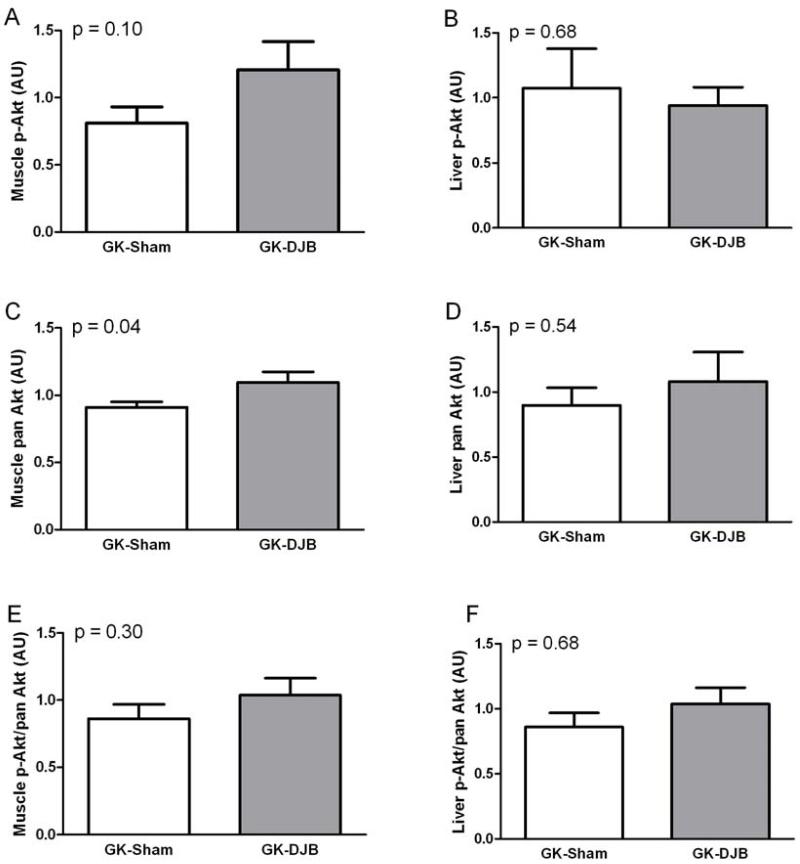

To investigate if the improvement in insulin sensitivity report by Rubino et al. is in skeletal muscle or liver (27), we measured insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation in the GK rats. In skeletal muscle, DJB increased Akt content and tended to increase insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation (Figure 2). In the liver, DJB had no effect on Akt content or insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation. There was no difference in the ratio of phosphorylation-to-total protein for Akt in either muscle or liver.

Figure 2.

Skeletal muscle (A,C,E) and liver (B,D,F) insulin-induced Akt in Sham and DJB operated GK rats. Skeletal muscle pan Akt was significantly increased in GK-DJB and GK-Sham. Mean ± SE. GK-Sham: muscle (N = 12) and liver (N = 4); GK-DJB: muscle (N = 9) and liver (N = 6).

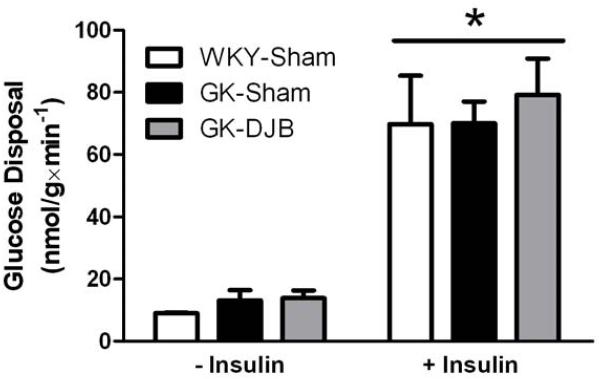

To investigate if changes in muscle Akt potentially translate into functional improvements in glucose disposal, we performed hindlimb perfusion to measure skeletal muscle glucose disposal in WKY-Sham, GK-Sham, and GK-DJB. As expected, insulin increased glucose disposal (Figure 3). However, there was no difference in glucose disposal between groups either with or without insulin.

Figure 3.

Plantaris glucose disposal with (+) or without (−) insulin in sham and DJB operated WKY and GK rats. There was no interaction between surgical groups and conditions. There was a significant Main effect of insulin to increase glucose disposal. There was no difference in glucose disposal between surgical groups. Mean ± SE. WKY-Sham: N = 3; GK-Sham: N = 4; and GK-DJB: N = 5.

DISCUSSION

The principal finding of the present study from GK rats is that DJB surgery does not increase glucose tolerance, skeletal muscle insulin-induced signaling or glucose disposal, or liver insulin-induced signaling. These findings are in contrast to the improvements in glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity by Rubino and colleagues (27, 28), but are consistent with recent findings in humans where only modest improvements in glycemic control were observed following DJB (15, 17).

It is now well established that bariatric surgery and in particular Roux-en Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is an effective treatment for type 2 diabetes. In a recent meta-analysis, RYGB was shown to return diabetic patients to euglycemia in ~80% of cases (4). In fact, our group was the first to report that RYGB held the potential to reverse diabetes (24) and that RYBG increases skeletal muscle insulin-induced glucose disposal (16). However, the mechanisms for improvements in glycemic control and muscle glucose disposal have remained elusive as they could be due to weight loss, food restriction, and/or foregut bypass. In part due to the rapidity with which glycemic control improves, we have proposed that bypassing of the foregut held considerable potential to explain these improvements (25). Therefore, the reports from Rubino and colleagues demonstrating that bypassing of the foregut with DJB surgery improved glycemic control and insulin sensitivity in GK rats in the absence of weight loss or food restriction were exciting (27, 28). In the current report, we performed DJB to reproduce these findings in GK rats and then explicitly to investigate the source of improved insulin sensitivity by DJB as both skeletal muscle and liver could be in part responsible.

In contrast to results from Rubino et al. (27, 28), neither fasting glucose nor glucose tolerance were different between DJB and Sham GK rats. As evidenced in Figure 1, GK rats demonstrated a poor insulin response to glucose independent of surgical intervention. This finding is consistent with previous reports of poor β cell function in adults as well as juvenile GK rats (22, 26). We therefore considered the possibility that poor insulin responsiveness to glucose could mask our ability to identify improvements in glucose tolerance with DJB.

To investigate if insulin-induced signaling was being masked by poor insulin secretion in GK rats, exogenous insulin was administered to discern if differences in insulin-induced signaling were present between DJB and Sham GK rats. GK rats have been reported to have reduced insulin-induced insulin receptor phosphorylation (9) and reduced insulin-induced Akt activity (19). In the current study, it was found that the surgical intervention provided somewhat ambiguous results in skeletal muscle, with increased pan Akt and a trend toward increased p-Akt in DJB compared to Sham, but no difference in Akt when expressed as p-Akt/pan Akt. In liver, there was no difference in any Akt associated measurement.

Akt is downstream of PI3K in the insulin transduction pathway and we have previously found reduced Akt phosphorylation in insulin resistant skeletal muscle (2). It was thus reasoned that if Akt signaling was indeed improved by DJB, then improvements in insulin-induced skeletal muscle glucose disposal should be evident. In contrast to this reasoning, there was no difference in muscle glucose disposal in response to DJB (Figure 3). Interestingly, there was no difference in muscle glucose disposal between either group of GK rats and WKY suggesting that differences in glucose tolerance between WKY and diabetic GK are due to inadequate pancreatic insulin secretion and likely reduced hepatic insulin sensitivity, but not muscle insulin sensitivity in GK compared to WKY rats.

In adults, skeletal muscle accounts for approximately 40% of total body weight and skeletal muscle is the primary site (~90%) for insulin-mediated glucose uptake (11). Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is a hallmark decrement in T2DM in humans (8, 23) and has been proposed to be the precipitating event leading to type 2 diabetes (23). Given the lack of skeletal muscle insulin resistance, our findings suggest that the GK rat may not be an adequate animal model to investigate the mechanisms of type 2 diabetes etiology and treatment.

In the current investigation, GK rats were used because it was previously reported that DJB reverses T2DM and insulin resistance in this rodent model of T2DM (27, 28). In contrast to these findings, we did not observe an improvement in glucose control, insulin signaling, or muscle glucose disposal following DJB. One possible reason for the discrepancy between the current results and those of Rubino and colleagues is the use of antibiotics. While Rubino and colleagues did not report any use of antibiotic treatment, we found it necessary to prophylactically treat rats with antibiotics to ensure adequate recovery. Antibiotic use has been shown to improve glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity (5, 6, 21). However, it should be noted that antibiotics are necessary when performing RYGB in humans and yet improvements in glycemic control do occur rapidly following RYGB (24, 25). In addition, in the current study both groups of GK demonstrated elevated fasting glucose compared to WKY (Figure 1) suggesting that diabetes persisted post-operatively in both groups of GK rats.

In humans, the initial case report from Cohen et al. from 2 T2DM patients was very encouraging in which complete reversal of T2DM occurred following DJB determined by normalized fasting blood glucose (89 and 77 mg/dl at 9-mo post-op) and HbA1c (5.0 and 5.7% at 9-mo post-op) and both patients were off all diabetes medications (7). More recently, Ferzli et al. found more modest improvements in fasting blood glucose (209 to 154 mg/dl, not significant) and HbA1c (9.4 to 8.5%) at 12-mo post-op with patients no longer on diabetes medications or reduced diabetes medications (15). Geloneze et al. reported similar modest findings with improvements in fasting blood glucose (184 to 157 mg/dl, not significant) and HbA1c (8.9 to 7.8%) at 24-wk post-op again with patients on reduced or completely off diabetes medications (17). Thus, while DJB appears to provide some improvements in T2DM, it does not provide the robust improvements in T2DM as RYGB questioning in part the role of the foregut.

In summary, we have demonstrated that DJB does not increase glucose tolerance, insulin-induced Akt signaling in liver or muscle, or skeletal muscle glucose disposal in GK rats. Diabetes in GK rats appears to be due to impaired glucose-induced insulin secretion and not impaired peripheral insulin resistance. Our findings also suggest that the GK rat may not be an adequate animal model to investigate the mechanisms of type 2 diabetes etiology and treatment. Whether DJB is able to improve skeletal muscle insulin resistance in animal models of type 2 diabetes remains to be identified.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by an East Carolina University Research Development grant (TP Gavin) and National Institute on Health grant-R01 DK046121 (GL Dohm).

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Diabetes Association Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2002. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:917–932. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brozinick JT, Jr, Roberts BR, Dohm GL. Defective Signaling Through Akt-2 and -3 But Not Akt-1 in Insulin-Resistant Human Skeletal Muscle: Potential Role in Insulin Resistance. Diabetes. 2003;52:935–941. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, Schoelles K. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Jensen MD, Pories WJ, Bantle JP, Sledge I. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2009;122:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, Burcelin R. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2008;57:1470–1481. doi: 10.2337/db07-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou CJ, Membrez M, Blancher F. Gut decontamination with norfloxacin and ampicillin enhances insulin sensitivity in mice. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program. 2008;62:127–137. doi: 10.1159/000146256. discussion 137-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen RV, Schiavon CA, Pinheiro JS, Correa JL, Rubino F. Duodenal-jejunal bypass for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in patients with body mass index of 22-34 kg/m(2): a report of 2 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:195–197. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corcoran MP, Lamon-Fava S, Fielding RA. Skeletal muscle lipid deposition and insulin resistance: effect of dietary fatty acids and exercise. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:662–677. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dadke S, Kusari J, Chernoff J. Down-regulation of insulin signaling by protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B is mediated by an N-terminal binding region. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23642–23647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeFronzo RA, Ferrannini E, Simonson DC. Fasting hyperglycemia in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: contributions of excessive hepatic glucose production and impaired tissue glucose uptake. Metabolism. 1989;38:387–395. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(89)90129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeFronzo RA, Jacot E, Jequier E, Maeder E, Wahren J, Felber JP. The effect of insulin on the disposal of glucose: results from indirect calorimetry and hepatic and femoral venous catheterization. Diabetes. 1981;30:1000–1007. doi: 10.2337/diab.30.12.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeFronzo RA, Jacot E, Jequier E, Maeder E, Wahren J, Felber JP. The effect of insulin on the disposal of intravenous glucose. Results from indirect calorimetry and hepatic and femoral venous catheterization. Diabetes. 1981;30:1000–1007. doi: 10.2337/diab.30.12.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dohm GL, Kasperek GJ, Tapscott EB, Beecher GR. Effect of exercise on synthesis and degradation of muscle protein. Biochem J. 1980;188:255–262. doi: 10.1042/bj1880255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolan PL, Tapscott EB, Dorton PJ, Dohm GL. Contractile activity restores insulin responsiveness in skeletal muscle of obese Zucker rats. Biochem J. 1993;289(Pt 2):423–426. doi: 10.1042/bj2890423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferzli GS, Dominique E, Ciaglia M, Bluth MH, Gonzalez A, Fingerhut A. Clinical improvement after duodenojejunal bypass for nonobese type 2 diabetes despite minimal improvement in glycemic homeostasis. World J Surg. 2009;33:972–979. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-9968-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman JE, Dohm GL, Leggett-Frazier N, Elton CW, Tapscott EB, Pories WP, Caro JF. Restoration of insulin responsiveness in skeletal muscle of morbidly obese patients after weight loss. Effect on muscle glucose transport and glucose transporter GLUT4. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:701–705. doi: 10.1172/JCI115638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geloneze B, Geloneze SR, Fiori C, Stabe C, Tambascia MA, Chaim EA, Astiarraga BD, Pareja JC. Surgery for nonobese type 2 diabetic patients: an interventional study with duodenal-jejunal exclusion. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1077–1083. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krein SL, Funnell MM, Piette JD. Economics of diabetes mellitus. Nurs Clin North Am. 2006;41:499–511. v–vi. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krook A, Kawano Y, Song XM, Efendic S, Roth RA, Wallberg-Henriksson H, Zierath JR. Improved glucose tolerance restores insulin-stimulated Akt kinase activity and glucose transport in skeletal muscle from diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. Diabetes. 1997;46:2110–2114. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.12.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Membrez M, Blancher F, Jaquet M, Bibiloni R, Cani PD, Burcelin RG, Corthesy I, Mace K, Chou CJ. Gut microbiota modulation with norfloxacin and ampicillin enhances glucose tolerance in mice. Faseb J. 2008;22:2416–2426. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-102723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Movassat J, Bailbe D, Lubrano-Berthelier C, Picarel-Blanchot F, Bertin E, Mourot J, Portha B. Follow-up of GK rats during prediabetes highlights increased insulin action and fat deposition despite low insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:E168–175. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00501.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Etiology of insulin resistance. Am J Med. 119:S10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pories WJ, Caro JF, Flickinger EG, Meelheim HD, Swanson MS. The control of diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) in the morbidly obese with the Greenville Gastric Bypass. Ann Surg. 1987;206:316–323. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198709000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG, Long SB, Morris PG, Brown BM, Barakat HA, deRamon RA, Israel G, Dolezal JM, et al. Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 1995;222:339–350. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199509000-00011. discussion 350-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Portha B, Serradas P, Bailbe D, Suzuki K, Goto Y, Giroix MH. Beta-cell insensitivity to glucose in the GK rat, a spontaneous nonobese model for type II diabetes. Diabetes. 1991;40:486–491. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.4.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubino F, Forgione A, Cummings DE, Vix M, Gnuli D, Mingrone G, Castagneto M, Marescaux J. The mechanism of diabetes control after gastrointestinal bypass surgery reveals a role of the proximal small intestine in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Ann Surg. 2006;244:741–749. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000224726.61448.1b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubino F, Marescaux J. Effect of duodenal-jejunal exclusion in a non-obese animal model of type 2 diabetes: a new perspective for an old disease. Ann Surg. 2004;239:1–11. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000102989.54824.fc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]