Abstract

Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases are intensely studied enzymes because of their importance in the establishment of the genetic code and their connection to disease and medicine. During the advancement of this field, several assays were developed. Despite many innovations, the sensitivity, simplicity, and reliability of the radiometric assays (that were among the first to be developed) have ensured their continued use. Four activities are measured by these assays: active site titration, amino acid activation, aminoacylation, and post-transfer editing (deacylation). In an effort to maintain the advantage of these assays, while enhancing throughput, reducing waste, and improving data quality, a universal 96-well filter plate format was developed. This format facilitates the assays for all 4 of the widely studied activities.

Keywords: Transfer RNA, filter plate, editing, scintillation counting, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase, ATP-PPi exchange, aminoacylation, charging

Introduction

The discovery of the genetic code ranks as one of the greatest achievements of the last century. Crick proposed that RNA adaptors could link information carried in genes to their corresponding gene products—proteins [1]. It was later discovered that (in most organisms) each of the canonical 20 amino acids could be covalently linked to a cognate transfer RNA (tRNA) that bears the anticodon triplet of the code corresponding to the particular amino acid [2; 3; 4]. The covalent linkage of amino acids to the adaptor molecules (tRNAs) is catalyzed by a set of 20 universal enzymes—aminoacyl tRNA synthetases (one for each amino acid).

The awareness that aminoacyl tRNA synthetases (AARSs) establish the genetic code gave investigators ample motivation to pursue the molecular mechanism of these enzymes. In more recent years, attention has also been placed on their medical relevance, through development of synthetase inhibitors as antimicrobial agents [5; 6] and, more recently, the identification of expanded functions in mammals that link signal transduction pathways and control of gene expression to translation [7]. And even mild disruption of one of the canonical activities—editing for suppression of mistranslation—leads to neurodegeneration [8].

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases establish the genetic code via a two-step reaction:

| (1) |

| (2) |

In the first step, a highly reactive aminoacyladenylate (AA-AMP) is formed through condensing ATP with the carboxylate of the amino acid (AA). The second reaction utilizes this activated species to esterify the amino acid to 3′-end of the tRNA (AA-tRNA). The sum of eqs 1 and 2 results in the specific attachment of amino acids to their cognate tRNAs, thereby linking each amino acid to its triplet anticodon imbedded within the tRNA.

Some AARSs are inherently error-prone in the amino acid activation step [9; 10]. Hydrolytic activities that clear misactivated amino acids sharply improve fidelity [11; 12; 13] and thereby prevent mistranslation [8; 14; 15; 16]. For instance, alanyl-tRNA synthetase (AlaRS) misactivates serine or glycine [17; 18]. A domain distinct from the active site for catalysis of Eqs 1 and 2 prevents mischarged tRNAs from being released for participation in translation (eqn 3) [17; 18; 19; 20].

| (3) |

Using a variety of procedures, each of the reactions of Eqs 1, 2 and 3 can be studied. Active site titration [21] and amino acid-dependent ATP-PPi exchange assays [22] monitor the reaction depicted by Eqn 1, while the reactions in Eqs 2 and 3 are monitored by assays for aminoacylation [23] and deacylation [24], respectively. These assays serve to kinetically dissect the enzymatic activities of any tRNA synthetase.

Radiometric assays for AARSs were established in early work. The basis of most all assays is a radiolabelled product that is captured on a solid support (such as, filter paper, or activated charcoal). While these assays are sensitive and straightforward, they suffer from low throughput due to laborious washing steps and the lack of a multichannel format. Additionally, for measurement of AA-tRNA, stubborn product adsorption on filter paper results in a time- and concentration-dependent release of product into the scintillant [25]. Further, many amino acids generate high background due to “sticking” of the free amino acid to the filter paper.

As a result of these drawbacks, many assays have been developed to replace traditional assays for amino acid activation (by amino acid-dependent ATP-PPi exchange), active site titration, aminoacylation, and editing (by deacylation of mischarged tRNA). Low throughput is a prime motivation to replace these assays and, additionally, non-radiometric approaches are desired as replacement for traditional radioactivity-based methods. Innovations to replace the proven historical assays have included coupled spectrophotometric [26; 27] and fluorescent assays [28]. Although many of the alternative approaches are innovative, they often lack the sensitivity (spectrophotometric) and simplicity of the historical radiometric assays.

Two existing formats offer both sensitivity and are amenable to a high-throughput format. One was developed by Wolfson and coworkers, and overcomes the limitations of amino acid concentration that exists with conventional aminoacylation assays (the tRNA is labeled instead of the amino acid) [29]. Despite its great utility, particularly for rapid kinetic experiments [30], it remains to be widely adopted, possibly because it has not been streamlined. (It requires TLC separation of reactants and quantitation by phosphoimaging.) Another method, the “scintillation proximity” approach [31], is perhaps the most useful but, for many laboratories, the required beads are too costly.

With these considerations in mind, we were motivated to “renovate” the established historical assays while maintaining their basic principles. Specifically, we sought to enhance throughput, while maintaining simplicity. All of these assays were developed with a wide range of users in mind. Each was validated on standard scintillation counters or a 96-well beta counter. Because these advances, although simple in appearance, greatly facilitated the progress of several ongoing projects in our laboratory, the details are given here in a practical format that should be amenable to widespread application.

Materials and methods

Materials

Table I gives a list of key materials together with vendor and catalog numbers and brief comments. Counting of single sample vials was accomplished in a BeckmanLSC LSV 6500 scintillation counter or a PE 1450 Microbeta Trilux counter for plates.

Table I.

Summary of materials used for universal plate assay

| Product | Assay used | Supplier | Catalog # | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multichannel Pipet (p10, p20, p200) | All | Rainin | L12-10 L12-20 L12-200 |

•Excellent performance with small volumes |

| Low-profile PCR plates | All | Fisher | 05-500-63 | •Low profile is ideal for manipulating small reactions. Also, can be pre-cut to save cost. |

| 1MultiScreenHTS HV, 0.45 μm, clear | All | Millipore | MSHVN4550 | •NA |

| 1MultiScreenHTS HV, 0.45 μm, opaque | Charging | Millipore | MSHVN4B50 | •Can be directly read in Microbeta plate reader in cassette 1450-106 |

| 96 Well Flexible Pet Microplate | All | Perkin Elmer | 1450-401 | •For reading in cross-talk hindering Microbeta cassette #1450-401 |

| General collection plate | All | Fisher | 12-565-502 | •Primarily used for collection when transferring to vials is planned |

| Vacuum manifold | ATP-PPi exchange, aminoacylation | Millipore | MSVMHTS00 | •For washing plates |

| Punch tips | ATP-PPi exchange | Millipore | MADP19650 | •Use in conjunction with tip punch tool (describe in text) |

| Large orifice p200 pipette tips | Active site titration, ATP-PPi exchange | Fisher | 21-197-2A | •Large orifice prevents charcoal from clogging tip upon mixing |

| Sealing tape | All | Perkin Elmer or Whatman | 1450-461 7704-0001 |

•For sealing plates prior to mixing |

| MultiScreen liner | Aminoacylation | Perkin Elmer | 1450-433 | •For preventing scintillant leaks in conjunction with microbeta cassette 1450-106 |

| Optiphase Supermix scintillant | All | Perkin Elmer | 1200-439 | •Suitable for large sample to scintillant ratios |

| P200 multichannel pipettor | All | NA | NA | •Any P200 that will accept normal tips for dispensing larger volumes of acids and bases and use with the large orifice tips. |

| Activated charcoal | ATP-PPi exchange, Active site titration | Fisher | CX0645-1 | Charcoal is suspended in 0.5% HCl to make a 10% (w/v) solution |

Other filter materials are available from Millipore but were not tested here.

RNA preparation

Transfer RNA (E. coli tRNAAla(GGC) or E coli tRNAThr) was produced by in vivo transcription with plasmid pWW-ectRNAAla for the overproduction of E. coli tRNAAla(GGC) and pWFW1015 for E. coli tRNAThr (Waas & Schimmel, unpublished). A 100-ml overnight culture of pWW-ectRNAAla or pWFW1015 in DH5α in LB-Ampicillin was diluted into 10-L of LB-ampicillin and grown (37 °C) to mid-log phase. Induction of overexpressed tRNA was accomplished by addition of IPTG (667 μM) for 24 hours. Cells were harvested and lysed by phenol (pH 4.7). Total RNA was precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in 90 ml buffer W5 (Clonetech, Mountain View, CA). The tRNA was isolated through use of a Nucleobond AX 10,000 GIGA column (Clonetech) followed by ethanol precipitation. The quantity of tRNAAla at this stage represented >80 % of the total tRNA (>1400 pmoles alanine acceptance/A260). Overproduction and purification of tRNAThr from cells harboring plasmid pWW-EctRNAThr was achieved similarly. Total bovine tRNA was purchased from EMD Biosciences, (San Diego, CA). To produce mischarged tRNAAla the overexpressed purified tRNAAla (13 μM) was aminoacylated in the presence of editing deficient C666A/Q584H AlaRS (2 μM), [3H]-Ser (64 μM), ATP (100 μM) and the assay buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 20 mM KCl, 2 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2). Similarly, reactions were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature, quenched with 0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 5), passed through a G25 microspin column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), ethanol precipitated, and resuspended in 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 5). These conditions achieved mischarging levels of 15–30%.

Protein expression and purification

Plasmids encoding human AlaRS (pBAD18/21b-huAlaRS), A734E human AlaRS (pBAD18/21b-huAlaRS(A734E)), mouse AlaRS (pH8GW-mAlaRS) are described elsewhere [8], Mutant C723A mouse AlaRS (pH8GW-mAlaRS(C723A)) was constructed by QuikChange mutagenesis on pH8GW-mAlaRS. Finally, a plasmid for the expression of S. cerevisiae AlaRS (pH8GW-yAlaRS) was constructed by PCR of a yeast cDNA clone, recombination of the PCR product using the Gateway cloning system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) ultimately into pH8GW. Plasmid pH8GW is described elsewhere [32]. For protein expression, the selected plasmid was transformed into BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Overnight cultures were grown (37 °C) in LB-amp/chloramphenicol, diluted 100-fold into 5 liters LB-amp/chloramphenicol, and grown (37 °C) to 0.5–0.6 OD600. Cultures were then shaken 20 minutes at 4 °C, transferred to room temperature and induced for 4–12 hours with 0.2% arabinose (pBAD constructs) or 200 μM IPTG (pH8GW constructs). Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 40 ml 1X Ni-NTA lysis/wash buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole) plus 5 mM β-ME and a single protease inhibitor tablet (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), lysed by sonication, and purified by Ni-NTA chromatography. If further purification was warranted, the buffer was then exchanged by 2-cycles of concentration in a Centriprep-30 and dilution into buffer A (20 mM Tris (pH 7.65), 10 mM NaCl, 20 mM β-ME). Protein was loaded onto a MonoQ HR 5/5 (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ)) and eluted with a gradient of 10–500 mM NaCl. Fractions of highest purity (>90%) were pooled and concentrated by Centriprep-30. Glycerol was added to 33% and DTT to 5 mM, and aliquots were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. E. coli AlaRS (wild type and C666A/H584Q) were purified as previously described [33]. Concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay [34]. Concentration of active enzyme was determined by active site titration [21].

Active site titration

The concentration of enzyme active sites was determined at 25 °C with 20 mM alanine, 5 μM AlaRS, 50 μM γ-[32P]-ATP in assay buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 20 mM KCl, 2 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2). Up to twelve 40 μl reactions (0.8–4 μCi γ-[32P]-ATP) were initiated at once by mixing enzyme with reaction mix in 96-well low-profile PCR plates. Although even greater quantities of radioactivity can be used, this quantity yields ample signal. This amount (~15–20,000 cpm per time-point) is chosen to minimize cross-talk. Time points (5–10 μl) were quenched into PVDF MultiScreen filter plates containing 20 μL of 7% HClO4 plus 80 of μL 10% charcoal slurry in 0.5% HCl. This amount of charcoal is sufficient for capturing all of the ATP in solution (i.e., the background is the same as when employing larger quantities of charcoal). After completion of all time points, the slurry was mixed up and down by pipetting with large orifice pipette tips. The samples were centrifuged into a collection plate and transferred to scintillation vials. Alternatively, if a plate reader is available, the samples can be centrifuged into a flexible Perkin-Elmer collection plate with 180 μl of Supermix scintillant. The plate is then closed off with sealing tape, mixed by inversion and counted directly. To minimize crosstalk (unwanted contribution of signal to adjacent wells), the flexible collection plates are used in conjunction with microbeta cassette, (#1450-401, Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA) and programmed for crosstalk correction.

Amino acid activation by ATP-PPi exchange

ATP-PPi exchange assays [35] were performed at 25 °C with 15.6 nM-1000 nM alanine, 25 nM wild type AlaRS, 0.5 mM sodium [32P]-PPi, 2 mM ATP in assay buffer. Up to twelve 30 μl reactions (5–25 μCi of [32P]-PPi in each reaction) were initiated at once by mixing enzyme with reaction mix in 96-well low-profile PCR plates. Time points (typically, 3–5 μl) were quenched into PVDF MultiScreen filter plates (Millipore) containing 200 μl of 10% charcoal/0.5% HCl and 50 μl of 1 M HCl/200 mM sodium pyrophosphate. Quenched aliquots were mixed with the charcoal slurry by pipetting up and down 10 times with large orifice tips. The charcoal was then washed 4 times (by pipetting up and down 10 times) with 200 μl 1 M HCl/200 mM sodium pyrophosphate on a 96 well MultiScreen vacuum manifold.

Two options exist for development of the sample. First, the charcoal can be dried to a fine powder (~30 min in a fume hood) and a disposable punch tip along with a simple punch tool (Supplemental figure 1) can be used to punch the samples into scintillation vials. Second, the ATP can be liberated from the charcoal by 2 extractions with 140 μl of 2 M Ammonia/60% ethanol. (Extraction involved pipetting up and down 20 times to mix followed by centrifugation into a collection plate). Samples are then added directly to scintillation vials for counting. Alternatively, if samples are collected in a flexible Perkin Elmer plate, they can be evaporated to dryness and resuspended in 200 μl of Supermix scintillation cocktail and counted in the Microbeta plate reader with the appropriate Microbeta cassette (#1450-401) programmed for cross-talk correction.

Aminoacylation assays

Aminoacylation assays were typically performed at 25 °C with 5 nM mouse AlaRS, 0.45–80.6 μM tRNAAla, 107 μM alanine, 4 mM ATP, and 4 ng/μl of inorganic pyrophosphatase (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) in assay buffer. Up to twelve 20 μl reactions (2.5 μCi 3H-Ala per reaction) at once were initiated by mixing enzyme with reaction mix in 96-well low-profile PCR plates. Samples (typically, 2–4 μl) were quenched into wells of Multiscreen filter plates containing 70 μL of 180 mM NaOAc/HOAc (pH 3), 1 mg/mL herring sperm DNA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After all time points were collected, an equal volume of 20% TCA was added to precipitate the nucleic acids. The plate was briefly agitated for mixing, transferred to a MultiScreen vacuum manifold, and washed 3–6 times with 200 μl 5% TCA containing 100 mM cold alanine followed once with 95% ethanol (washing is done by directly adding solution under vacuum with no agitation or pipetting up and down). Upon drying after completion of the washing steps, 70 μl of 100 mM NaOH is added to elute the sample (simultaneously resuspends the precipitate, and liberate the amino acid by hydrolysis of the aminoacyl ester bond). After addition of NaOH, the plate was briefly agitated (<2 minutes). If using opaque MultiScreen filter plates, scintillant can be directly added and, after brief mixing, the plate can be counted. If cross talk is a concern, the sample can be centrifuged into a flexible plate, with 180 μl of Supermix scintillation cocktail, mixed and counted (in cassette #1450-401). Lastly, if a plate reader isn’t available, the sample can be centrifuged into a collection plate and the samples can be transferred to scintillation vials.

Deacylation assays (amino acid liberation)

Up to twelve 20 μl reactions (typically 10–50,000 cpm per reaction) at once were initiated in 96-well PCR plates by mixing mouse AlaRS (5 nM) with reaction mix (assay buffer plus purified overexpressed E. coli tRNAAla (0.08–2.5 μM) that has been mischarged with [3H]-Ser. Reactions were incubated at 25 °C and stopped at several time intervals by addition of a reaction aliquot (typically, 2–4 μl) to PDVF MultiScreen filter plates containing 40 μL of 180 mM NaOAc/HOAc (pH 3), 1 mg/mL herring sperm DNA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After all time points were collected, an equal volume of 20% TCA was added to precipitate the nucleic acids. The plate was briefly agitated for mixing followed by separation of the free amino acid from intact (precipitated) aminoacylated substrate by centrifugation into a flexible collection plate with 180 μl of scintillant. Finally, the filtrate and scintillant were mixed and counted. Alternatively, the samples can be centrifuged into a collection plate and the filtrates can be transferred to scintillation vials for counting. To determine background hydrolysis, enzyme dilution buffer was added instead of buffer with enzyme. To determine 100% product (and therefore “% AA liberated”), NaOH (20–50 mM) was added to the reaction to liberate all AA from tRNA during the time course.

Results

Strategy

Discontinuous assays are the alternative to assays that measure the real-time enzymatic production of product. In contrast to continuous assays, where an entire time-course, potentially involving thousands of points that are determined by pipetting into a single tube or cuvette, each time-point must be manipulated individually in the discontinuous format. The major bottleneck of the discontinuous format is that only one reaction and one time point can be manipulated at a time. Most of the assays used to monitor AARSs are of the discontinuous or “stopped” format and are subject to this limitation. Hence, our motivation for improving throughput was to expand the number of reactions and time-points that could be manipulated at one time. Also, because most assays require extensive and time consuming wash steps, data acquisition is slowed and large volumes of radioactive acidic waste are generated. So, streamlining the wash procedures can further enhance the assay efficiency, cut reagent costs, and decrease disposal fees. Finally, both aminoacylation and deacylation assays require spotting of radioactive AA-tRNA product onto acidified Whatman filter paper, followed by washing away soluble, unincorporated radioactive amino acid. But adsorption of the radioactive free AA results in inconsistent counting between samples and a sample drift over time [25]. Further, background from free amino acid (as discussed above) is frequently encountered. Therefore, to isolate product from substrate by a means other than capture onto filter paper was a key objective.

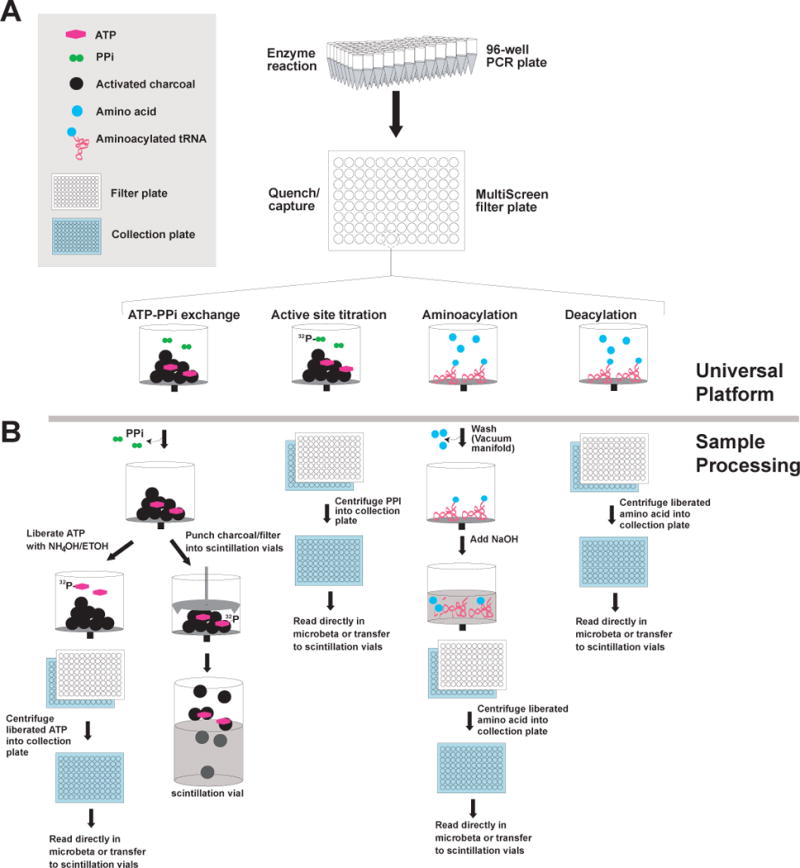

Universal solution for diverse aminoacyl tRNA synthetase assays

The assays for tRNA synthetase activities (active site titration, ATP-PPi exchange, aminoacylation, and deacylation) typically employ adsorption of product to insoluble material (i.e., filter paper or activated charcoal), followed by washing of adsorbent to remove unincorporated label. Despite the different adsorbents, we found that filter plates could be used as a universal platform (Figure 1A). Using these plates, throughput was enhanced, not only because of the ability to initiate up to 12 reactions at once, but also because the plate could be washed on a vacuum manifold. Throughput was enhanced further with the addition of a plate reader capable of reading isotope particle emissions. Because they offer a removable bottom rigid skirt for isolation of individual filters, MultiScreen filter plates (Millipore) were chosen. Specialized punch tools allow for isolation of the filter and the contents of the well. The punch tools were adapted for direct use in the versatile Wallac Microbeta (Perkin Elmer) plate counter. Depending on the assay, the product was either eluted and collected as filtrate, or directly collected as the filter plus insoluble material (Figure 1B). All tRNA synthetase assays were adapted using these plates.

Figure 1. Overall Scheme of universal plate based format.

A. All assays share the same platform for initiation of reactions through quenching and product capture in the MultiScreen plates. B. The assays employ different modes of sample processing.

Active site determination by active site titration

In order to circumvent errors inherent in protein quantitation methods, active site titration was developed for AARSs by Ferhst [21]. The rapid burst of formation of the adenylate from ATP and AA (Eq 1), followed by slow turnover of the adenylate, can be used to determine the number of functioning active sites in a given enzyme preparation. This assay is particularly important for an accurate determination of active site concentrations. Starting with 32P-γ-ATP, bound adenylate is adsorbed to activated charcoal, while radioactive inorganic phosphate (formed via the synthetase activation reaction and subsequent hydrolysis by inorganic pyrophosphatase (eqn 1)) remains free in solution and is centrifuged, aspirated and counted. Because all other experiments are based on an accurate calculation of the number of active sites, replicates and multiple enzyme concentrations are needed to ensure greater accuracy. This redundancy requires an enablement of high-throughput.

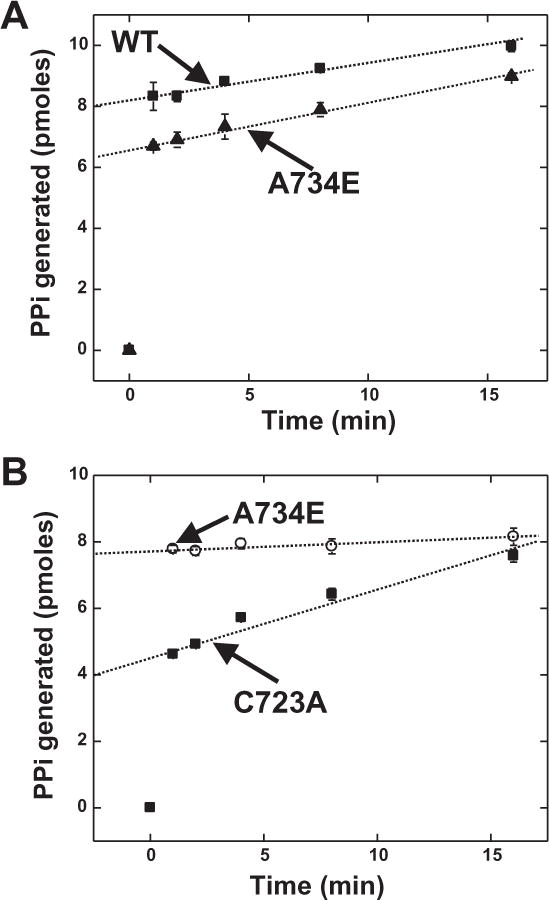

The main limitation for this assay, other than throughput, is costly individual filters, awkward non-disposable filter manifolds (requiring clean up), or centrifugation steps followed by aspiration of liquid away from charcoal. The aspiration of liquid in this situation is precarious because of the tenuous nature of the charcoal pellet. To adapt to the plate-based assay, reactions were set up in a column (of wells) of 96-well low-profile PCR plates. In an adjacent column of wells, the reaction was initiated with enzyme aliquots. Finally, time points were quenched into PVDF MultiScreen filter plates. Representative data are given in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Active site titration using MultiScreen filter plates with a variety of enzymes.

Assays were performed as described in methods at 25 °C (pH 7.5). Time points were quenched into the charcoal–containing MultiScreen filter plates and centrifuged into a scintillant-filled flexible counting plate. The samples were counted in a Microbeta plate reader. A. Human WT and A734E AlaRS. B. Mouse WT and C723A AlaRS. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean of three independent measurements.

These data show that precision is high (small error bars) when conducting the assay in this format. The slow turnover of product allows for extrapolation to the y-axis for accurate enzyme concentration determination. Based on the specific activity value and known concentration of ATP, the cpm value from the y-axis intercept is converted to moles of ATP (the enzyme concentration and reagents are designed in such a way that moles of ATP = moles of active sites) [21]. The results in figure 2 are consistent with what would be expected based on total protein concentrations determined by the Bradford assay. The concentration of AlaRS determined in this manner is usually 30–50% relative to the Bradford assay (precisely what is calculated from the data in figure 2). Further, in a separate experiments, data generated using the old method of separation and this method gave indistinguishable results within the standard deviation of the means. Finally, the sensitivity of the assay is limited to ~20 pmoles.

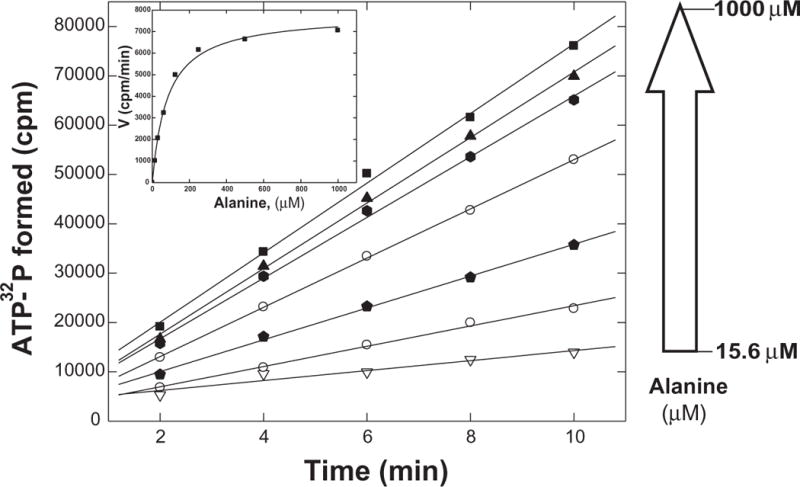

Amino acid activation by ATP-PPi exchange

The historical assay for tRNA synthetases was amino acid-dependent incorporation of 32P from PPi into ATP. The ATP exchanged from the reverse of Eq. 1 is adsorbed to activated charcoal and free PPi is washed away, while the labeled ATP-bound charcoal is subjected to scintillation counting.

The main limitation of this assay is laborious washing steps and low throughput. Therefore, by applying time points to a PVDF 96-well MultiScreen filter plate (Millipore) containing the activated charcoal, washing can be efficiently executed on a MultiScreen vacuum manifold (Millipore). Figure 3 shows representative data from this type of assay. Not surprisingly (since this assay is modified from the more traditional method only in the mechanics of charcoal separation), the kinetic constants derived with this method for capturing the ATP-bound charcoal are within the range of what would be expected for AlaRS (kcat = 30 s−1, Km(alanine) = 83 μM). E. coli AlaRS has been reported to have a kcat of 80 s−1 and Km(alanine) = 340 μM [36]. Further, the sensitivity of this assay is comparable to the assay done in the standard format (limited to 200–400 pmoles). Despite an appearance of variability in punching the charcoal into scintillation vials, the results are very reproducible. Although preferred by us, if punching of the filters is not chosen, 32P can be eluted from the charcoal with ethanolic base (The main drawback to the base extraction is the repeated suspension of the charcoal by pipetting up and down).

Figure 3. ATP-PPi exchange using MultiScreen filter plates.

Assays were performed at 25 °C with 15.6, 31.3, 62.5, 125, 250, 500, 1000 μM alanine, 25 nM mouse AlaRS (pH 7.5). Time points were quenched into MultiScreen filter plates, washed 4 times with 200 μl 1M HCl/200 mM sodium pyrophosphate and the plates were dried. The charcoal was then isolated from the wells by punching the contents into scintillation vials using the punch tool (Supplemental figure 1) with the disposable punch tips (Millipore).

Aminoacylation assays

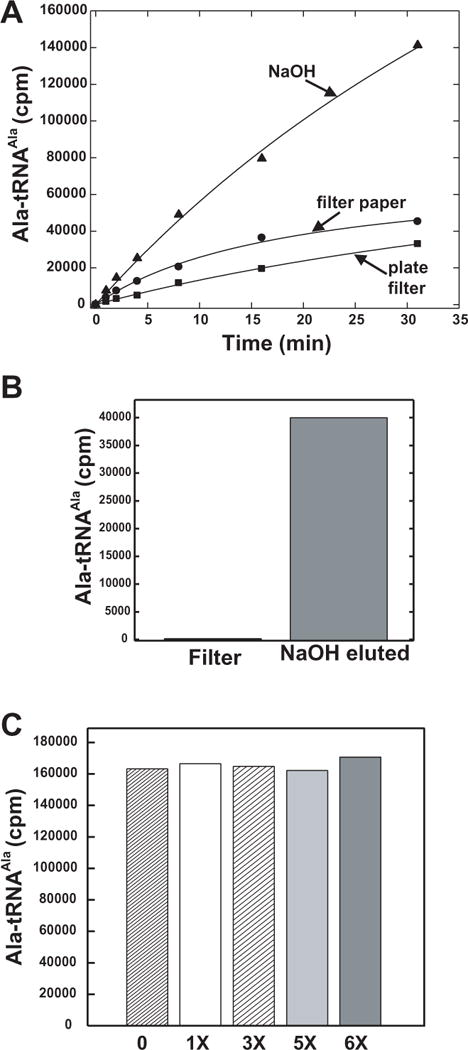

Aminoacylation analysis of AARSs traditionally suffers from poor data quality. Precipitation by TCA of products from assays on to various filter materials is a common format. For AARSs, tRNA aminoacylated with an isotopically labeled amino acid is precipitated. Besides lack of throughput, this assay suffers from long washing steps and, too frequently, a high background due to “stickiness” of the free, labeled amino acid. Most of all, however, many precipitation assays suffer from the problem of stubborn adsorption of product onto the filter surface (with aminoacylation assays being no exception). Therefore, release of material into scintillant is inherently variable. Normally, this variability can be overcome by time-consuming vigorous mixing and soaking in scintillant.

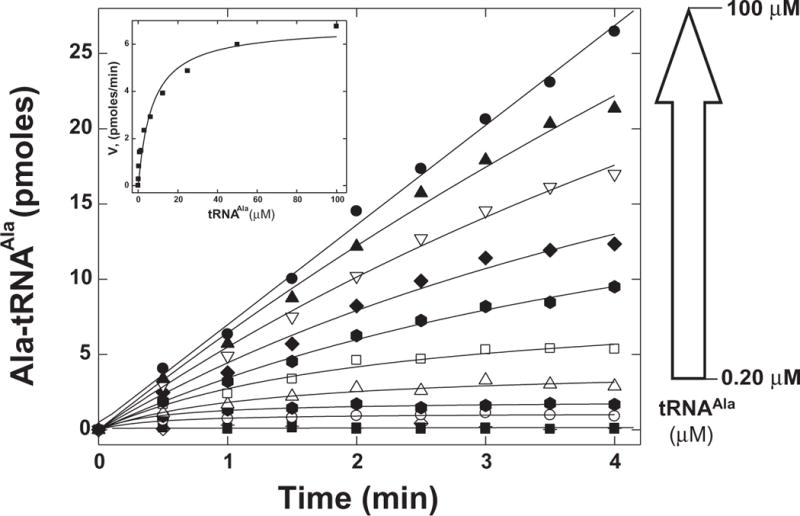

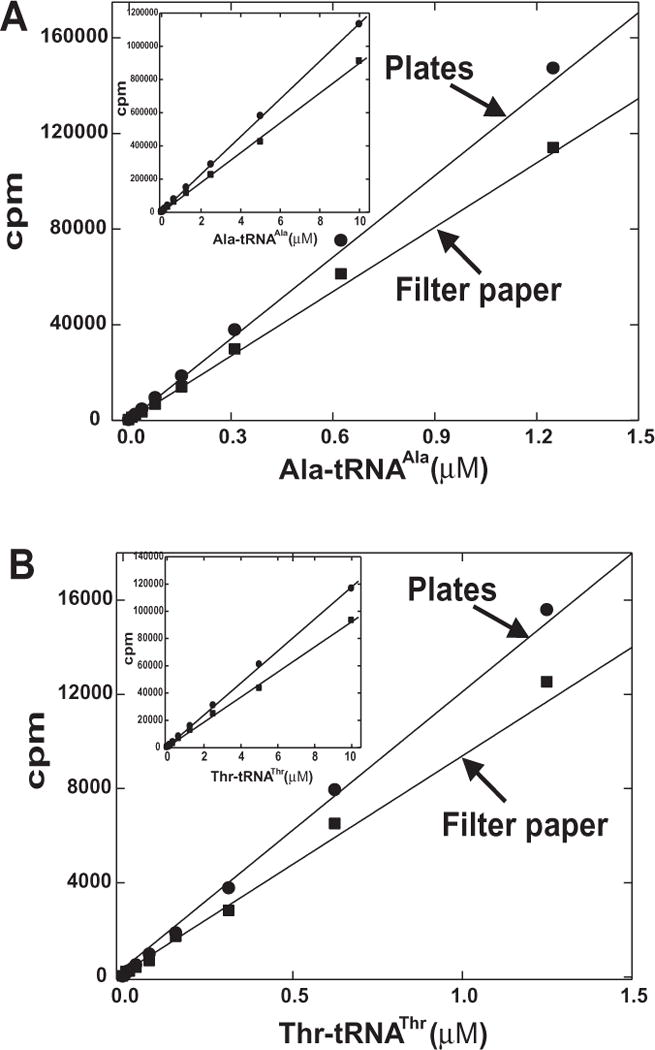

To simultaneously resolve all of the above drawbacks, the assay was adapted to the Multiscreen plates. After precipitation and quenching into the wells, samples were washed over a MultiScreen vacuum manifold (Millipore). Using this format, background was reduced to negligible levels by using large quantities of unlabelled amino acid that were incorporated into relatively small volumes of wash solution. (In contrast, the traditional Whatman filter paper method requires larger volumes of wash solution containing large quantities of amino acid). Therefore, much higher specific activities can be used before background becomes an issue. The sample was then “liberated” from the filter by the addition of 100 mM NaOH. This addition improved the release of product, when compared to the traditional method of dissolving the precipitate directly into the scintillant (Figure 4A). Further, it efficiently “eluted” all product leaving only background levels of product behind (Figure 4B). The precipitated material withstands extensive washing, without “leaching” from the plate to any detectable degree (Figure 4C). Figure 5 shows the result of a kinetic assay using the new format and mouse AlaRS. These data show that, upon titration with increasing amounts of tRNA, a typical Michalis-Menten plot is obtained, yielding a kcat of 3.8 s−1 and Km of 7.2 μM. This is comparable to the values obtained using the conventional filter paper method for human AlaRS (kcat = 1.5 s−1 and Km = 5.4 μM.

Figure 4. Recovery, base elution, and retention of aminoacylated tRNAAla on MultiScreen plates.

A. Timecourse comparing plates, filter paper and base elution of plates. Assays were performed at 25 °C with WT AlaRS, 53 μM alanine, and 5 μM E. coli tRNAAla. Time-points were quenched in plates or filter paper and washed with 5% TCA. Filters (Whatman filter paper or PVDF from Multiscreen plates) or base eluted samples (from the MultiScreen plates) were directly added to scintillant, vortexed and counted by scintillation. B. Efficiency of elution of base treated plates. After elution by base, the filter was recovered and the amount of radioactive material retained was compared to that which eluted. C. Retention of aminoacylated alanylated-tRNA upon vacuuming the reaction through the plate and washing with 200 μl 5% TCA once, three times, 4 times, 5 times and 6 times washing on vacuum manifold.

Figure 5. Aminoacylation of tRNAAla with mouse AlaRS developed with MultiScreen filter plates.

Assays were performed at 25 °C with 10 nM WT mouse AlaRS, 53 μM alanine, and, 0.20, 0.39, 0.78, 1.56, 3.12, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 μM tRNAAla. Time-points were quenched, counted by scintillation, and initial rates then derived. These rates were fit to the Michaelis-Menton equation (inset).

During the time of this manuscript preparation, a similar plate-based assay was described by for aminoacylation [37]. In contrast to the method presented here, material is left on the filter for counting. Additionally, TCA was used to both quench and precipitate the sample. However, TCA alone is not sufficient to efficiently precipitate the tRNA under some circumstances (such as low concentration of product). To circumvent the problem of efficient precipitation at low concentrations of tRNA we employed carrier DNA in our assays. To maintain solubility of the carrier DNA prior to the addition of the time point and simultaneously quench the enzyme reaction, we quenched the reactions in cold, (pH 3) 180 mM NaOAc-HOAc with 1 mg/ml herring sperm DNA. This solution efficiently quenched AlaRS activity and provided ample acidity at the low temperature to stabilize the aminoacyl-ester bond. Following agitation of the plate after all time points were collected, an equal volume of 20% TCA was added to precipitate nucleic acids. The plate was then washed and developed as indicated above.

Figure 6 shows that the recovery of two aminoacyl tRNAs is linear across concentrations from <1 nM (0.01 pmoles) to > 1 μM. In contrast, with the filter paper method, linearity tends to fade with increasing concentration. In other experiments, we found that even higher concentrations of acetic acid and addition of EDTA can also be used for reaction quenching. Another possible quenching additive (and possible carrier for precipitation) can come from addition of large amounts of pepsin, which is active at pH 2–3 and relatively inexpensive. Since AARSs are diverse enzymes, it is advisable for users to ensure that their particular enzyme is efficiently quenched in the conditions described above. Further, typical 5–20% TCA precipitation will suffice in most cases for efficient precipitation. Nevertheless, addition of carrier in the quench format described above has been shown to work efficiently across a broad range of concentrations for all tRNAs tested in our lab (meeting or exceeding the conventional filter paper efficiency).

Figure 6. Recovery of aminoacylated product by MultiScreen plates and Whatman filter paper.

A. Recovery of Ala-tRNAAla. B. Recovery of Thr-tRNAThr. Acylated tRNA was prepared as described in methods. Dilutions of acylated tRNA were added to carrier DNA containing acetate quench mix in MultiScreen plates or on to filter paper. Samples were washed and developed as described. Inset, data given over the concentration range of 0 to 10 μM.

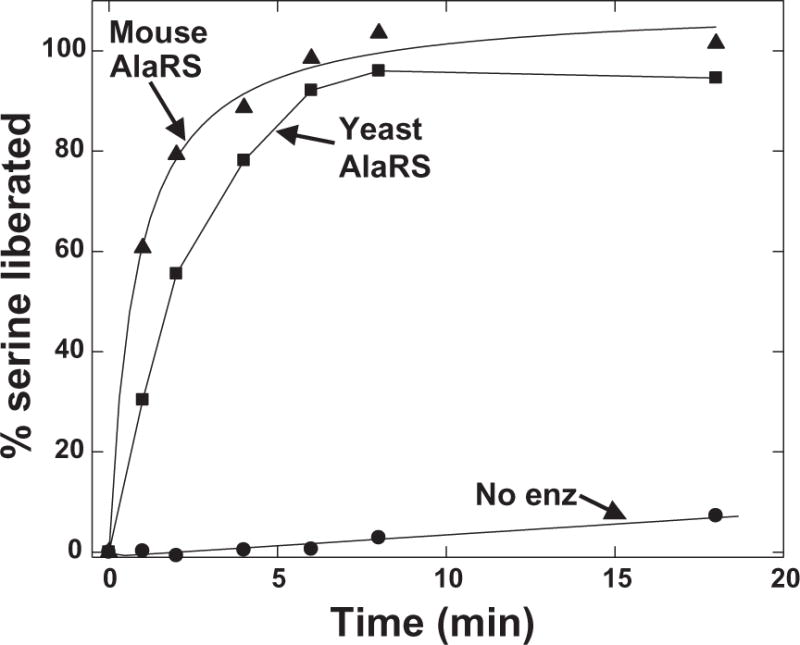

Deacylation assays

Deacylation measures the loss of AA-tRNA (Eq. 3), so that the same precipitation principle described for the aminoacylation assay can be used. Because the first few time points have high amounts of labeled AA-tRNA, the early time points tend to have inherent variability. To circumvent this problem and to streamline the assay, the amount of AA liberated rather than amount of AA-tRNA remaining on the filter was measured. The assay was performed along the same lines as the aminoacylation assay, except that after quenching (into cold, pH 3 180 mM NaOAc-HOAc acid with 1 mg/ml herring sperm DNA, followed by precipitation with cold 20% TCA), the liberated amino acid was captured as filtrate in a collection plate by centrifugation. Samples were either added to individual scintillation vials or collected in a spin plate that held scintillant, and then mixed and read in a Microbeta plate reader. The quality of data achieved with this assay is seen in Figure 7. These data show that, by detection of the liberated amino acid, enzymatic hydrolysis is readily measured over the control with no enzyme. Also, background hydrolysis that increases at a low rate with time did not have the erratic variability seen with the conventional filter paper method.

Figure 7. Assay for deacylation of Ser-tRNAAla.

Assays were performed at 25 °C with 10 nM mouse or yeast AlaRS, 5 μM [3H]-Ser-tRNAAla (pH 7.5). Time-points were quenched as described in the methods and counted by scintillation. The initial rates were plotted as % serine liberated from tRNAAla.

For all the amino acids tested thus far (Ala, Gly, Ser, Thr, Trp), we have not encountered a problem with their failing to elute from the plate due to adhering to the PVDF (note, it is coated, hydrophilic PVDF). However, this possibility should be examined for any amino acid under study, to ensure a free passage of AA through PVDF. If necessary, a second elution can be devised that washes off the amino acid while not disrupting the AA-tRNA (e.g., ethanol, isopropanol, etc.)

Discussion

Although there have been many alternatives proposed for aminoacyl tRNA synthetase assays, the simplicity and sensitivity of the historical assays remains the standard for many researchers in the field. However, these assays also suffered from poor throughput. Our solution maintains the basic features and approach of all of the assays, but adapts them into a high throughput format.

Three points are worth nothing. First, the greatest contribution to throughput occurs at the initial stage of performing the enzymatic reaction itself and the subsequent washing steps. The addition of the plate reader is an added benefit. Despite lacking this capability, the advantages are numerous (from the trivial (tracking of samples) to the more significant (ability to run more reactions at one in parallel)). Second the cost of the plates is not as prohibitive as may first seem to be. For example, one plate is ~1/10 the cost of the spin filters we formerly used for ATP-PPi exchange and active site titration assays. In the case of aminoacylation and deacylation assays, the plates are more costly compared to filter paper. The extra materials cost is offset by labor conservation, higher precision, reduced radioactive waste volumes, and the quality of the data produced by the base liberation from the PVDF filter. Also, the rows or columns, on the plate, that are used in one assay can be annotated, while the remaining portion of the plate can be used in a second assay. Third, the assay format described within is robust, but AARSs are highly diverse enzymes so we encourage researchers to adapt the conditions described within for optimal performance with their specific enzyme-tRNA system (just as they would with a new system with the conventional format).

Lastly, while neither we nor others have developed an absolute replacement for a radiometric basis for activity measurement, the efficiencies achieved with our methods reduce the amount of radioactive reagents that are required. It should also be recognized that, although these assays were tailored for AARS activities, the principles can be applied to any nucleic acid precipitation assay or ATPase or ATP-PPi exchange assay. For instance, ATP-PPi exchange is commonly used when analyzing the adenylation activity of nonribosomal peptide synthetases [38].

Supplementary Material

A. The end of a P200 tip is cut and pushed into the trimmed tip of a P1000 tip. (The pipet-receiving part of the p200 tip is removed so that it can traverse the wells of the Multiscreen plate). B. The tool is then used as an adaptor to go over the shaft of an individual punch pin of the punch tips (Millipore) (These punch tips are arrayed in a 96-well cartridge). The tool can then be used to sharply drive the punch tip through the filter and into a scintillation vial.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Paul O’maille of the Salk Research Institute for his gift of the pH8GW and Marissa Mock for insightful comments and editorial review of the manuscript. Finally, we thank those involved in submitting experiments to be tested with the new assay format (Leslie Nangle, Esther Chong, Francella Otero, John Reader). This work was supported by grant GM 15539 from the National Institutes of Health and by a grant from the National Foundation for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Crick FHC. On protein synthesis. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1957;12:138–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter CW., Jr Cognition, mechanism, and evolutionary relationships in aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1993;62:715–748. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.003435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giege R, Puglisi JD, Florentz C. tRNA structure and aminoacylation efficiency. Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology. 1993;45:129–206. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60869-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lapointe J, Giege R. Transfer RNAs and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. In: Trachsel H, editor. Translation in Eukaryotes. CRC Press, Inc.; Boca Raton: 1991. pp. 35–69. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schimmel P, Tao J, Hill J. Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases as targets for new anti-infectives. Faseb J. 1998;12:1599–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tao J, Schimmel P. Inhibitors of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases as novel anti-infectives. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2000;9:1767–75. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.8.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park SG, Ewalt KL, Kim S. Functional expansion of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and their interacting factors: new perspectives on housekeepers. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:569–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JW, Beebe K, Nangle LA, Jang J, Longo-Guess CM, Cook SA, Davisson MT, Sundberg JP, Schimmel P, Ackerman SL. Editing-defective tRNA synthetase causes protein misfolding and neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;443:50–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakubowski H, Goldman E. Editing of errors in selection of amino acids for protein synthesis. Microbiological Reviews. 1992;56:412–429. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.3.412-429.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pauling L. Festschrift fur Prof. Dr. Arthur Stoll. Birkhauser-Verlag; Basel: 1957. The probability of errors in the process of synthesis of protein molecules; pp. 597–602. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldwin AN, Berg P. Transfer ribonucleic acid-induced hydrolysis of valyladenylate bound to isoleucyl ribonucleic acid synthetase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1966;241:839–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eldred EW, Schimmel PR. Rapid deacylation by isoleucyl transfer ribonucleic acid synthetase of isoleucine-specific transfer ribonucleic acid aminoacylated with valine. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1972;247:2961–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fersht AR. Biochemistry. 1977;16:1025–1030. doi: 10.1021/bi00624a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doring V, Mootz HD, Nangle LA, Hendrickson TL, de Crecy-Lagard V, Schimmel P, Marliere P. Enlarging the amino acid set of Escherichia coli by infiltration of the valine coding pathway. Science. 2001;292:501–504. doi: 10.1126/science.1057718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nangle LA, Motta CM, Schimmel P. Global effects of mistranslation from an editing defect in mammalian cells. Chem Biol. 2006;13:1091–100. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seburn KL, Nangle LA, Cox GA, Schimmel P, Burgess RW. An active dominant mutation of glycyl-tRNA synthetase causes neuropathy in a Charcot-Marie-Tooth 2D mouse model. Neuron. 2006;51:715–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beebe K, Ribas De Pouplana L, Schimmel P. Elucidation of tRNA-dependent editing by a class II tRNA synthetase and significance for cell viability. Embo J. 2003;22:668–75. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsui WC, Fersht AR. Probing the principles of amino acid selection using the alanyl-tRNA synthetase from Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:4627–37. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.18.4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dock-Bregeon A, Sankaranarayanan R, Romby P, Caillet J, Springer M, Rees B, Francklyn CS, Ehresmann C, Moras D. Transfer RNA-mediated editing in threonyl-tRNA synthetase. The class II solution to the double discrimination problem. Cell. 2000;103:877–84. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sankaranarayanan R, Dock-Bregeon AC, Rees B, Bovee M, Caillet J, Romby P, Francklyn CS, Moras D. Zinc ion mediated amino acid discrimination by threonyl-tRNA synthetase. Nature Structural Biology. 2000;7:461–5. doi: 10.1038/75856. [see comments] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fersht AR, Ashford JS, Bruton CJ, Jakes R, Koch GLE, Hartley BS. Active site titration and aminoacyl adenylate binding stoichiometry of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Biochemistry. 1975;14:1–4. doi: 10.1021/bi00672a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldwin AN, Berg P. Purification and properties of isoleucyl ribonucleic acid synthetase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:831–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoskinson RM, Khorana HG. Studies on Polynucleotides. Xli. Purification of Phenylalanine-Specific Transfer Ribonucleic Acid from Yeast by Countercurrent Distribution. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:2129–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eldred EW, Schimmel PR. Investigation of the transfer of amino acid from a transfer ribonucleic acid synthetase-aminoacyl adenylate complex to transfer ribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1972;11:17–23. doi: 10.1021/bi00751a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisenthal R, Danson M, editors. Enzyme Assays: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lloyd AJ, Thomann HU, Ibba M, Soll D. A broadly applicable continuous spectrophotometric assay for measuring aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2886–92. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.15.2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu MX, Hill KA. A continuous spectrophotometric assay for the aminoacylation of transfer RNA by alanyl-transfer RNA synthetase. Anal Biochem. 1993;211:320–3. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brennan JD, Hogue CW, Rajendran B, Willis KJ, Szabo AG. Preparation of enantiomerically pure L-7-azatryptophan by an enzymatic method and its application to the development of a fluorimetric activity assay for tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase. Anal Biochem. 1997;252:260–70. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolfson AD, Uhlenbeck OC. Modulation of tRNAAla identity by inorganic pyrophosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5965–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092152799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uter NT, Perona JJ. Active-site assembly in glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase by tRNA-mediated induced fit. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6858–65. doi: 10.1021/bi052606b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macarron R, Mensah L, Cid C, Carranza C, Benson N, Pope AJ, Diez E. A homogeneous method to measure aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase aminoacylation activity using scintillation proximity assay technology. Anal Biochem. 2000;284:183–90. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beebe K, Merriman E, Ribas De Pouplana L, Schimmel P. A domain for editing by an archaebacterial tRNA synthetase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5958–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401530101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beebe K, Ribas De Pouplana L, Schimmel P. Elucidation of tRNA-dependent editing by a class II tRNA synthetase and significance for cell viability. The Embo Journal. 2003;22:668–75. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calendar R, Berg P. The catalytic properties of tyrosyl ribonucleic acid synthases from Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Biochemistry. 1966;5:1690–1695. doi: 10.1021/bi00869a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu MX, Filley SJ, Xiong J, Lee JJ, Hill KA. A cysteine in the C-terminal region of alanyl-tRNA synthetase is important for aminoacylation activity. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12260–6. doi: 10.1021/bi00206a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ochsner UA, Young CL, Stone KC, Dean FB, Janjic N, Critchley IA. Mode of action and biochemical characterization of REP8839, a novel inhibitor of methionyl-tRNA synthetase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4253–62. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.10.4253-4262.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ehmann DE, Shaw-Reid CA, Losey HC, Walsh CT. The EntF and EntE adenylation domains of Escherichia coli enterobactin synthetase: sequestration and selectivity in acyl-AMP transfers to thiolation domain cosubstrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2509–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040572897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. The end of a P200 tip is cut and pushed into the trimmed tip of a P1000 tip. (The pipet-receiving part of the p200 tip is removed so that it can traverse the wells of the Multiscreen plate). B. The tool is then used as an adaptor to go over the shaft of an individual punch pin of the punch tips (Millipore) (These punch tips are arrayed in a 96-well cartridge). The tool can then be used to sharply drive the punch tip through the filter and into a scintillation vial.