Abstract

Androgen/androgen receptor (AR) signaling plays pivotal roles in the prostate development and homeostasis as well as in the progression of prostate cancer (PCa). Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) with anti-androgens remains as the main treatment of PCa, and it has been shown to effectively suppress PCa growth during the first 12–24 months. However, ADT eventually fails and tumors may re-grow and progress into the castration resistant stage. Recent reports revealed that AR might play complicated and even opposite roles in PCa progression that might depend on cell types and tumor stages. Importantly, AR may influence PCa progression via differential modulation of various cell deaths including apoptosis, anoikis, entosis, necrosis, and autophagic cell deaths. Targeting AR may induce PCa cell apoptosis, autophagic cell deaths and programmed necrosis, yet targeting AR may also suppress cell deaths via anoikis and entosis that may potentially lead to increased metastasis. These differential functions of AR in various types of PCa cell death might challenge the current ADT with anti-androgens treatment. Further detailed dissection of molecular mechanisms by which AR modulates different PCa cell deaths will help us to develop a better therapy to battle PCa.

Keywords: prostate cancer, androgen receptor, apoptosis, necrosis, autophagy, anoikis, entosis, cell death

1. Introduction

The abnormal increased cell proliferation and/or decreased cell death in prostate may lead to the development of prostate cancer (PCa), which is the second most leading cause of cancer death in men of North America1, 2. Importantly, the alteration of cell death signaling may also involve in PCa resistance to the hormone therapy and chemotherapy3–6, suggesting both cell death and cell proliferation may play key roles to influence PCa progression.

Androgen receptor (AR), a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily7–9, can be activated by its ligands, androgens, to regulate its target gene expression. Early studies documented well that AR played complicated yet vital roles in the progression of PCa10–12. Importantly, AR could either stimulate or suppress PCa progression via modulating cell proliferation or cell death with distinct mechanisms13–15.

This review will begin with brief discussion of the differential AR roles in proliferation within individual cells of PCa and then focus on differential AR roles in controlling 5 types of cell death pathways including apoptosis, anoikis, entosis, necrosis, and autophagic cell deaths.

2. AR plays differential roles in cell proliferation among various PCa cell populations

Since Huggins and Hodges12 provided the first in vivo evidence that targeting androgen/AR signaling via androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) could suppress PCa progression, ADT has become the main therapy for treatment of later stage PCa16. However, most of ADT failed in about two years and tumors continue to progress into the castration resistant stage17–19. Importantly, more and more studies suggested that AR might not only function as a stimulator to promote PCa cell growth, AR could also function as a suppressor to negatively control PCa progression13, 20–22. The differential functions of AR in PCa may depend on various cell types and tumor microenvironments.

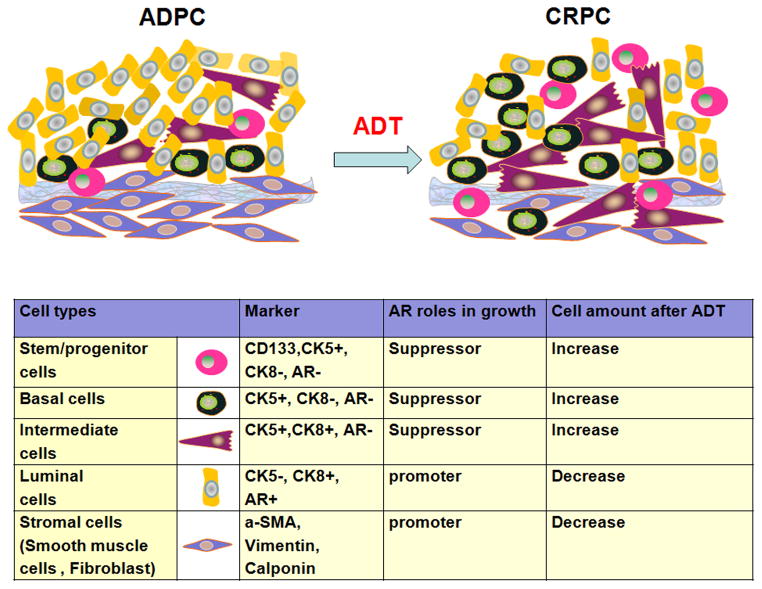

PCa is composed with mixture of cells in various differentiation stages, and might be derived from PCa stem/progenitor cells, which are CK8−, AR− and CK5+. Briefly, in the normal prostate, there are three kinds of epithelial cells: (1) CK5−/CK8+ luminal cells, (2) CK5−/CK8− intermediate cells, and (3) CK5+/CK8− basal cells (Fig 1). Stem/progenitor cells, marked by CK5+/CK8−, are able to differentiate into basal intermediate cells (CK5+/CK8+) and finally differentiate into luminal epithelial cells (CK5−/CK8+)23, 24. Bonkhoff et al demonstrated that castration could only kill the majority of luminal epithelial cells, but most of the basal cells remained alive25. Current ADT for advanced PCa, which targeted androgen/AR signaling, might diminish luminal cells, and increase stem/progenitor cell, basal cell and basal intermediate cell populations13. These results suggested that androgen/AR signaling might have different roles among different cell types and might partially explain why ADT would finally fail.

Fig. 1.

Androgen/AR signal plays differential roles in prostate cancer progress. Either promoting suppressing or promoting PCa growth dependents on various cell types. So the current ADT, which targets androgen, may lead to different results on individual cell type. After ADT, the androgen-dependent PCa (ADPC) may convert to CRPC. And the luminal cells and stromal cells will decrease, while the stem/progenitor cells, basal cells and intermediate cells will increase.

Here, we briefly summarize the differential roles of AR in the individual cells within tumors that might influence PCa progression as follows.

2.1. AR positive roles in PCa CK5−/CK8+ luminal epithelial cell growth

The terminally differentiated CK5−/CK8+ luminal epithelial cells represent the major PCa cell type and they are believed to be differentiated from the CK5+/CK8+ intermediate cells that derived from CK5+/CK8− stem/progenitor cells21, 26, 27. Niu et al generated TRAMP mice with deleted AR in PCa epithelial cells (pes-ARKO–TRAMP), and found knocking out AR in PCa epithelial cells led to increasing apoptosis in CK5−/CK8+ luminal epithelial cells (from 2% to 18%) as compared with wild-type TRAMP mice. This result suggested that AR might function with a positive survival role in PCa luminal epithelial cells.

Similar results were also obtained from CK8+/CK18+ LNCaP epithelial cells derived from lymph node of metastatic PCa28, 29, showing knocking-down AR with anti-sense oligonucleotides suppressed LNCaP cell growth30–32. Furthermore, AR also played positive roles in other CK5−/CK8+ PCa cells, such as CWR22Rv1 cells33, in which targeting AR with AR-siRNA resulted in suppression of cell growth34.

Together, results from various human PCa cell lines and TRAMP mouse model with AR deletion in epithelial cells suggested that AR might play positive roles in PCa CK5−/CK8+ luminal epithelial cells.

2.2. AR negative roles in PCa CK5+/CK8+ basal intermediate cell growth

During the differentiation from the CK5+/CK8− PCa stem/progenitor cells to CK5−/CK8+ luminal cells, some cells are characterized as CK5+/CK8+ basal intermediate cells. The PC-3 cell line that was derived from a human bone marrow prostate metastatic tumor35, is AR negative but expresses both CK5 and CK8, and therefore could be regarded as basal intermediate PCa cells. Litvinov et al transfected PC3 cells with a functional AR cDNA under strong promoter and found overexpression of AR in PC−3 cells might lead to suppression of cell growth36, 37, suggesting AR might play a negative role for basal intermediate-like tumor cell growth. Niu et al21 also used in vivo mouse model and confirmed that transfection of a functional AR in PC−3 cells resulted in suppression of orthotopic xenografted tumor growth.

2.3. AR negative roles in PCa CK5+/CK8− basal and stem/progenitor cell growth

Lee et al38 found that AR might suppress cell proliferation in CK5+ cells that may include basal epithelial cells and stem/progenitor cells. Addition of functional AR in the human CK5+/CK8− basal epithelial cell line (named Lifeline-basal or HPrE) or the mouse CK5+/CK8− stem/progenitor cell line (named mPrE) all led to suppressing their growth model studies. Further in vivo mouse model study confirmed these results and knocking-out AR in basal epithelial cells in the basal epithelium-specific ARKO mouse also led to increased proliferation of CK5+ cells38.

In summary, AR may play either positive or negative roles in PCa epithelial cell growth, depending on in which type of epithelial cell the AR expresses. AR could suppress the growth of CK5+/CK8− basal and stem/progenitor cells and CK5+/CK8+ basal intermediate cells, but promote or support the growth of CK8+ luminal epithelial cells.

2.4. AR positive roles in PCa stromal cells growth

Earlier tissue recombination studies showed that stromal–epithelial interaction is important for PCa progression39–41. Data from stromal-epithelial co-culture approaches also revealed that AR in human stromal WPMY1 cells could play a positive role to promote PCa growth and knocking down AR in WPMY1 cells suppressed PCa epithelial tumor cell proliferation21. Similar in vitro studies using the co-culture system also demonstrated that rat urogenital mesenchyme or bone marrow fibroblasts promoted LNCaP and other epithelial cells growth42, 43. Importantly, using mice lacking stromal AR, Lai et al found stromal AR could promote prostate tumorigenesis via induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines expression44.

In summary, these findings proved that stromal AR could play a positive role to promote PCa progression and concluded that AR could play either positive or negative roles in individual PCa cells to influence PCa progression.

3. Differential AR roles in 5 types of PCa cell death

In addition to influencing cell proliferation, AR could also modulate cell death to control PCa progression. In the normal prostate, controlling cell death is essential in maintaining tissue homeostasis and is a natural barrier to cancer development3, 4. Loss of this cell death control via various mechanisms may then lead to development of cancer. Furthermore, many genes that could regulate the cell death pathways and contribute to “resisting cell death”, which is one of the hallmarks of cancer development45, have been documented46–51. Importantly, recent studies also indicated that AR could play key roles to influence the PCa cell death via distinct mechanisms52–54, and more and more evidences suggested that targeting androgen/AR-mediated cell death signaling could also alter the PCa progression55–58.

The new classification of cell death established by the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death (NCCD) was based on molecular feature59. According to this classification, cell deaths can be roughly divided into: apoptosis (caspase dependent extrinsic apoptosis and caspase-independent intrinsic apoptosis), necrosis, autophagy cell death, and other tentative definitions of cell death modalities including anoikis, entosis, pyroptosis, netosis and cornification. In PCa, at least 5 types of cell death pathways have been observed and studied, including apoptosis60, necrosis61, 62, autophagy63, anoikis64, and entosis65 that will be discussed in the following sections.

Interestingly, recent studies found that AR might play differential roles in various cell death signaling. AR could either inhibit apoptosis66, necrosis62 and autophagy53, 67, yet enhance apoptosis, anoikis54 and entosis65. Furthermore, many studies suggested that apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy are related to tumor growth, yet both anoikis and entosis are more related to tumor metastasis (see the following sections). These interesting findings support the earlier discussion that AR may play a positive role in PCa tumor growth while it plays a negative role in metastasis68.

3.1. AR positive and negative roles in cell apoptosis

Kerr et al first suggested the term “apoptosis” and confirmed it as a general mechanism of controlled cell deletion, which is complementary to mitosis in the regulation of animal cell populations69. Deletion of apoptosis might cause uncontrolled cell proliferation and accumulation of cells, and finally result in some serious diseases, such as tumors. Therefore, one main direction of current tumor therapy strategy is targeting apoptosis4, 6, 70, 71. Apoptosis can be histologically determined by formation of small, roughly spherical or ovoid cytoplasmic fragments and can be determined by observing the apoptotic bodies under microscopy69, 72.

Recently, the NCCD divided apoptosis into extrinsic apoptosis and intrinsic apoptosis59. Extrinsic apoptosis has been applied to the instances of apoptotic cell death that are induced by extracellular stress signals that are sensed and propagated by specific transmembrane receptors while intrinsic apoptosis is known to be resulted from a bio-energetic and metabolic catastrophes coupled to multiple active execution mechanisms59.

Caspase plays a major role in apoptosis73. For example, caspase-3, -6, and -7 are directly responsible for proteolytic cleavages that lead to cell disassembly (act as effectors), and caspase-2, -8, -9, and -10 are involved in upstream regulatory events (act as initiators)74. The caspase family-mediated apoptosis74, 75 can be mediated via both receptor pathway and mitochondrial pathway76. Propagation of the cell death signaling ultimately leads to the activation of effector caspase-3, -6, and -7, culminating in the cleavage of various protein substrates that display the typical biochemical and morphological hallmarks of apoptosis71.

In addition to the caspase family, the Bcl-2 family proteins are also involved in apoptosis and regarded as the second set of apoptotic regulators. This family has been divided into three groups; group I members including Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, etc possess anti-apoptotic activity, whereas members of groups II (Bax) and III (Bid, Bix, etc) promote cell death77. The Bcl-2 family plays a vital role in the regulation of the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway, which plays an important role in most forms of drug-induced apoptosis78.

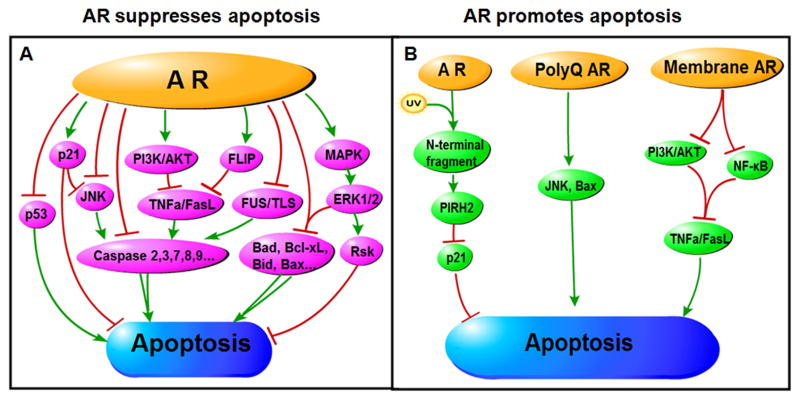

Similar to the above discussed the dual role of AR in PCa proliferation, AR also could modulate apoptosis in both positive and negative ways. AR could either promote79 or suppress66 apoptosis (Fig. 2) through modulating different signaling pathways80, and the AR influences on cell apoptosis would then depend on internal and/or external information the cells received from the tumor microenvironment81.

Fig. 2.

The major role of AR in apoptosis is a suppressor. However, in contrast to the main negative roles of AR in apoptosis, in some specific environment(exposing in UV), AR may induce apoptosis. Meanwhile, some specific AR(membrane AR or polyQ AR) may also promote apoptosis. A, AR can go through ①p53; ②21; ③JNK; ④PI3K/AKT; ⑤FLIP; ⑥ FUS/TLS; ⑦MAPK; ⑧Caspase family; ⑨Bcl-2 family to suppress Apoptosis. B, AR could also promote apoptosis via: ①PIRH2-p21 axis; ②JNK, Bax; ③PI3K/AKT and NK- κB.

3.1.1. AR negative roles in PCa cell apoptosis

Because the pro-proliferating role of AR has been established, the anti-apoptotic role of AR in PCa cells could also be expected, which might be deeply linked to the PCa development and progression82. There are many mechanisms by which AR protects cells from apoptosis, among which cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 (WAF1, CIP1, SDI1, or CAP20) is one of the important contributors. p21 has been proven to be able to protect against p53-mediated apoptosis83. Overexpression of p21 may induce cell cycle arrest and led to an apoptosis-resistant phenotype84. Lu et al showed that AR stimulated endogenous p21 mRNA and protein levels and functioned as an apoptosis inhibitor to promote PCa LNCaP cell growth85. They also found a functional androgen response element (ARE, AGCACGCGAGGTTCC) located at -200 bp of the p21 gene proximal to the promoter region and showed that androgen could enhance the p21 gene expression at the transcriptional level.

Besides p21, androgen/AR signaling could directly regulate p53 to suppress apoptosis52. Rokhlin et al found androgen could suppress the TNFR family (TNF-α/Fas)-induced apoptosis through inhibition of p53 expression and caspase-2 activation, and suppression of the TNFR family-induced apoptosis by androgen could then be enhanced by p53 knockdown52. Other studies also showed that androgen could block apoptosis induced by Fas activation and TNF-α86.

Kadowaki et al found that the AR-positive LNCaP cells were resistant to TRAIL-induced apoptosis, while the AR-negative PC-3 cells were sensitive87, suggesting AR might play negative roles in this type of apoptosis. Rokhlin et al also revealed that increased AKT might suppress the androgen-inhibited apoptosis52. Similar results also obtained from Sun et al showed androgen could activate PI3K and AKT1/AKT2, through AR, and consequently functioned as an anti-apoptosis factor in LNCaP cells88, 89.

Androgen/AR signaling could also suppress apoptosis by inhibiting Bad, the Bcl-2-associated death protein. Androgen activated MAPK and increased the phosphorylation of ERK-1 and ERK-2, and inactivated Bad, which resulted in inhibition of apoptosis90, 91. Brooke et al also found the expression of the RNA-binding protein FUS/TLS (Fused in Ewing’s Sarcoma/Translocated in Liposarcoma) was suppressed by androgen that resulted in suppression of PCa cells apoptosis92.

Interestingly, AR could also protect PCa cells from apoptosis via an androgen-independent manner. Diallo at el found that AR-negative PC-3 cells were more sensitive to the anti-cancer drug effect via inducing caspase-dependent apoptosis93 than PC-3 cells stably transfected with AR in the absence of androgen.

Other published papers showed that the down-regulation of AR induced PCa apoptotic death upon addition of proteasome inhibitor66 and docetaxel94. Liao et al showed that knockdown of AR via siRNA led to apoptotic death in PCa cells32. They further found both the cisplatin and the proteasome inhibitor induced caspase-3-associated cell death in AR-negative PC-3 cells while non-caspase-3 associated cell death was observed in AR-positive PC-3AR and LNCaP cells. In addition, they found that co-treatment with Bortezomib and the AR antagonist Casodex caused significant decrease in AR expression and led to caspase-3 activity increase in LNCaP and PC-3AR cells, suggesting AR might suppress caspase-3 expression66.

In summary, results from above suggested that androgen/AR signaling could play negative roles in PCa cell apoptosis (Fig. 2.).

3.1.2. AR positive roles in PCa cell apoptosis

In contrast to the main negative roles of AR in apoptosis, its positive roles have also been suggested47. Godfrey and his collages reported that AR could promote stress-induced cell death independent of its transcription activity in the androgen-independent PCa cells79. They showed that, upon exposure to stress (ultraviolet light and staurosporine), the N-terminal domain of AR (AR-N) would undergo proteasomal degradation which might lead to stress-induced apoptosis mediated by Bax47 and caspases79. Blockade of AR degradation, ectopic expression of Bcl-2 or selected caspase inhibitors can suppress this pro-apoptotic activity of AR79. This conclusion was confirmed by their further study95. In 2012, Lin et al demonstrated that UV might induce DNA damage and AR proteasomal degradation. This AR degradation produces the N-terminal domain that might then induce up-regulation of PIRH2 and p53 and down-regulation of p21, and finally resulted in cell apoptotic death95. This conclusion may suggest that AR can promote radiotherapy through PIRH2-p53-p21 axis. However, opposite results have also been reported, showing that AR could protect PCa from irradiation-induced apoptosis86. AR was also proven to improve photodynamic therapy (PDT)96 that might result in cell oxidative DNA damage and apoptosis. So, the exact role of AR in radiotherapy is complicated and still unclear. Other studies demonstrated that truncated PolyQ expression of AR gene promoted apoptosis through up-regulation of Bax and JNK97, 98, suggesting that the pro-survival/pro-death function of AR is mediated mainly by transcriptional regulation of apoptosis associated genes95

In addition to intracellular AR functions in apoptosis, it was suggested that membrane AR could induce apoptosis in PCa cells as well99, 100. Mechanism study showed that membrane AR activation triggers down-regulation of PI-3K/Akt/NF-kappaB activity and induces apoptotic responses via Bad, FasL and caspase-3 in PCa100.

Together, results from above suggested that androgen/AR signaling could play positive roles in PCa cell apoptosis.

Since both positive and negative roles of AR in PCa cell apoptosis have been reported, it is still arguable when and under what circumstances AR selectively plays its roles. To our knowledge, AR function is regulated by multiple signaling pathways and depending on different AR associate protein complexes, which indicates AR may induce or suppress cell apoptosis according to cell microenvironments and cell types. Besides, the anti-apoptosis and pro-survival function of AR (intracellular AR) is mediated mainly by transcriptional regulation of its target genes. In contrast, the pro-apoptosis function of AR (intracellular AR) is mainly transcription-independent, or mediated by membrane AR.

3.2. AR positive roles in promoting PCa cell anoikis

The interactions between cells and the extra-cellular matrix (ECM) play very important roles in the cell growth and cell death101–103. Aside from attachment to ECM, epithelial cells and/or endothelial cells could be induced by another type of cell death104, named as anoikis105, that resulted from insufficient cell-matrix interactions. Normal cells might use anoikis to prevent cell proliferation at inappropriate locations106 and cancer cells could also adapt to overcome anoikis and result in tumor growth and metastasis. Therefore, targeting anoikis might lead to suppressed tumor growth and metastasis106–108.

Based on several discovered mechanisms involving in anoikis109–112, the NCCD defined anoikis as an adherent cell-restricted lethal cascade that is ignited by detachment from the surrounding matrix with the following characteristics: (i) lack of β1-integrin engagement; (ii) down-regulation of EGFR expression; (iii) inhibition of ERK1 signaling and (iv) overexpression of the BCL-2 family member BIM59.

Anoikis has been linked to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process106 that involves the PCa metastasis. The strategy of combination therapy with targeting tumor vascularity (via anoikis) and impairing tumor initiation (via classic apoptosis) resulted in the significant therapeutic promise to battle metastatic PCa113.

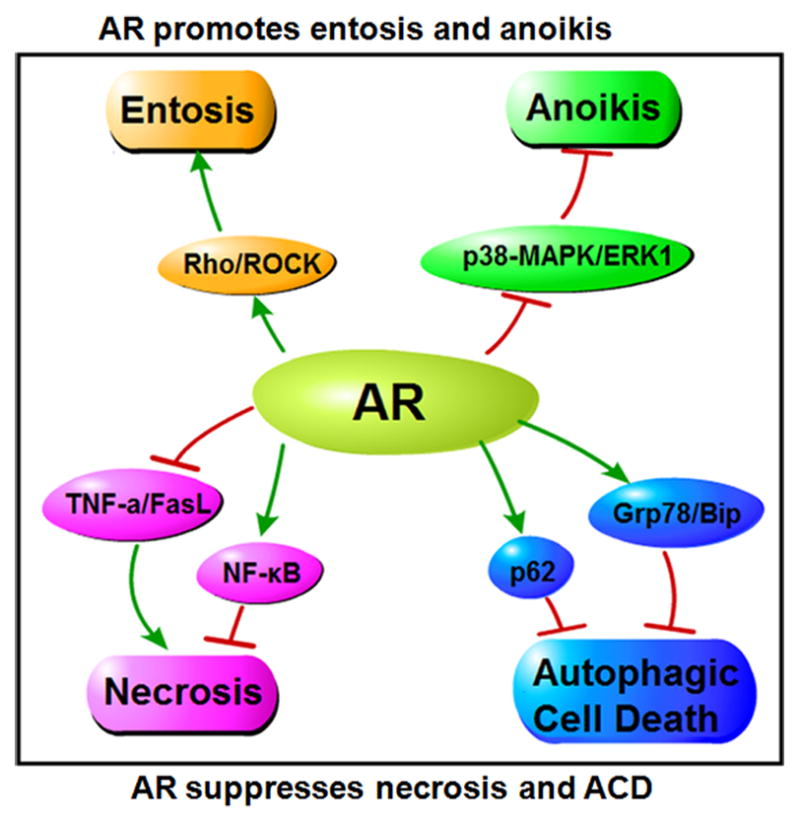

Ma et al first found that hepatic AR might play dual yet opposite roles to promote hepatocelluar carcinoma (HCC) initiation yet suppress HCC metastasis that involved the suppression of the phosphorylation/activation of p38 at later HCC stages54. Since p38 is a member of the MAP kinase family that might play important roles in anoikis114, 115, their results suggested that down-regulation of p38 by AR might result in increased anoikis (Fig. 3) that led to suppression of tumor metastasis54. Furthermore, they also found androgen/AR signaling could increase anoikis in LNCaP cells, suggesting that androgen/AR signaling could also regulate anoikis in some selective PCa cells, and provided another explanation why AR could suppress PCa metastasis (Ma et al, unpublished results).

Fig. 3.

In addition to apoptosis, AR may also regulate other kinds of cell death. Such as: ①AR enhances entosis through Rho/ROCK pathway; ②AR promotes anoikis through MAPK/ERK pathway; ③AR suppresses necrosis through TNFa/FasL and NF-kB pathway; ④ AR suppresses ACD via p62 and Grp78/Bip.

3.3. AR positive roles in enhancing PCa cell entosis

Overholtzer and his colleagues first introduced the term entosis to describe a non-apoptosis cell death mechanism linked to the way of clearing detached cells that might be accompanied with the cell-in-cell phenotype116. Entosis is defined as only a homogeneous live cell invasion phenomenon and only happens within the living cells and their neighborhood117–119. Furthermore, entosis is an active process that is formed by the invasion of one cell into another, rather than by engulfment116.

Even though both entosis and anoikis could be provoked by the loss of ECM interaction, entosis would not entail the activation of apoptotic executioners and is a non-apoptosis pathway, so is distinct from anoikis109. Entosis is also distinct from autophagy (see later section).

There are many fates for the internalized cells during entosis, such as undergoing the lysosome-mediated degradation process or undergoing cell division within the host cells116, 120. Entosis could also disturb the host cell cytokinesis resulting in aneuploidy and could be regarded as a non-genetic route to aneuploidy in human cancers121, 122. Overall, as the main outcome of entosis is the death of the internalized cells, it might represent a novel pathway to eliminate detached cancer cells, and thus its stimulation may offer a better outcome in clinical oncology116, 120.

Entosis was reported as a process that is independent of both caspase and Bcl-2 related cell death pathways, but it might depend on the activation of the small GTPase-RhoA, the ROCK1/ROCK2 in the engulfing cells116, 123. Other reports also suggested that Metallothionein 2A124 and Par3-Lgl125 could regulate entosis through the RhoA-ROCK pathway.

Wen et al65 found that androgen/AR signaling could enhance entosis through modulation of the RhoA/ROCK pathway (Fig. 3), as 10 nM DHT treatment exhibiting better effects to promote entosis compared to 1 nM DHT. Knocking-down AR suppressed entosis in PCa cells in the presence of both 1 and 10 nM DHT. Suppression of the RhoA-ROCK pathway with the inhibitor (Y-67236) or siRNA then resulted in blocking the androgen/AR-enhanced entosis. Importantly, clinical sample surveys found entosis phenomenon in the late castration resistant stage of PCa, compared to its absence in the early androgen dependent stage of PCa and non-tumor area including benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). These contrasting clinical data suggested that entosis might occur mainly at the late stage of PCa with increased invasion ability. Under this circumstance, the connection between PCa cells and ECM become weak (especially when the PCa cells invade into blood or lymph nodes). The diminished connection suggested that the actin polymerization and myosin II activity, regulated by RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway, might involve in the entosis-related PCa cell invasion. AR roles in entosis could be another reason to explain why AR could suppress PCa cells invasion.

3.4. AR negative roles in suppressing PCa cell necrosis

Laster et al first found both apoptosis and necrosis was responsive to the same trigger of TNF-α126. Accumulating evidences revealed that necrosis could also occur in a regulated manner127–129, and then a new term “necroptosis” was introduced to describe the programmed necrosis130. According to the suggestion from NCCD we here use “programmed necrosis” term. Programmed necrosis has been reported to be induced by several stimulations, such as alkylating DNA damage131, excitotoxicity132, and the activation of death receptors126. Other reports also suggested that proteins/kinases, such as death receptors of CD95, also known as Fas133, TNFR1 and TNFR2126, TRAILR1 and TRAILR2134 were involved in the initiation of progression of necrosis and RIP1/RIPK1, RIP3/RIPK3127, LMP and lysosomal135, mitochondrial and cytosolic hydrolases136 are all involved in the action of programmed necrosis. In addition, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by mitochondria can also contribute to the programmed necrosis137–139.

An early report indicated that androgen could protect renal cortical cells from programmed necrosis induced by vasopressin administration and suppression of androgen binding to AR via anti-androgen of cyproterone acetate increased programmed necrosis140, suggesting androgen/AR signaling might play a negative role in programmed necrosis.

Frezza et al reported that cisplatin and the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib might induce caspase-3-associated apoptotic cell death in parental PC-3 cells. In contrast, they could not induce necrosis cell death in LNCaP and PC-3AR cells66. Blocking androgen binding to AR via the anti-androgen Casodex in these two AR+ PCa cell lines might then lead to cell death via the caspase-associated apoptotic pathway after treatment with cisplatin and bortezomib, suggesting that blockade of androgen/AR signaling might be able to switch programmed necrosis to apoptosis in these PCa AR+ cell line66 and indicated that AR might play a negative role in programmed necrosis.

Liu et al found that 10 nM DHT could protect AR+ PCa cell lines including PC-3AR9 and C4-2 from the programmed necrosis induced by H2O2 or heat62. Knocking-down AR via siRNA in these PCa cell lines led to increase programmed necrosis, suggesting AR might play negative roles in programmed necrosis. Whether AR might go through modulation of the NF-κB pathway141 or death receptor pathway (such as Fas activation and TNF-α)86 to suppress the programmed necrosis might need further studies in the future.

3.5. AR negative roles in decreasing PCa autophagic cell death

In 1963, de Duve first suggested the term autophagy to describe the presence of single- or double-membrane vesicles that contain parts of the cytoplasm and organelles in various states of disintegration and called these sequestering vesicles autophagosomes 142. Recently, autophagy was described as a process in eukaryotes by which cytoplasmic cargo sequestered inside double-membrane vesicles (known as autophagosomes) would be delivered to the lysosome for degradation143. The NCCD suggested the term autophagic cell death (ACD) as a cell death instance that is mediated by autophagy, and could be suppressed by the inhibition of the autophagic pathway with chemicals (VPS34 inhibitor) and/or genetic means (down-regulation of essential autophagic modulators like AMBRA1, ATG5, ATG12 or beclin1)59.

Autophagy has essential roles in survival, development, and homeostasis processes143–147. In eukaryotic cells, autophagy, which is induced by stress and development, has double functions. Stress-induced autophagy can often exert cyto-protective functions to support the re-establishment of cell status, and inhibition of autophagy may induce cell death. On the other hand, the inhibition of autophagy may also result in inhibition of the developmental cell death59. There is a hypothesis that excessive autophagy may lead to suppression of cell growth. Most of the anti-cancer therapies that target ACD are based on this hypothesis148, 149 and some selective PCa therapies also target ACD53, 150–152.

Bennett et al found reduced androgen might result in increased autophagy51 and detailed mechanistic studies indicated that this suppression might be due to alteration of AR-mediated up-regulation of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperone Grp78/BiP67. They also found addition of the anti-androgen of Casodex to block androgen/AR signaling in LNCaP led to increased autophagy. Interestingly, combining 3-methyladenine to inhibit autophagy with ADT, with or without docetaxel treatment, resulted in better efficacy to suppress PCa progression67.

Jiang et al found knockdown of AR in AR positive cell lines, such as LNCaP or CWR22R human PCa cells led to increased autophagy, and addition of functional AR in AR negative cell lines, such as PC-3 cells, resulted in decreased autophagy, suggesting AR could play a negative role in regulating autophagy. Mechanism dissection indicated that AR might repress autophagy via modulation of p62 expression. Importantly, the therapeutic approach via targeting AR to increase autophagy with AR degradation enhancer ASC-J9® resulted in the suppression of PCa growth53.

Interestingly, Kung et al found that AR activation via non-androgens could also inhibit autophagy and the autophagy blockade might sensitize PCa cells to the Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor. So they suggested a therapy combining Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor with autophagy modulator might deserve further attention as a potential treatment for relapsed PCa153.

Taken together, results from above suggested that AR could play a negative role in autophagy to promote PCa cells growth.

4. AR differential effects in PCa progression based on its positive or negative roles in cell deaths

None of above described cell deaths contributes to PCa growth and metastasis equally, and PCa progression is not dependent entirely on any single cell death pathway. Generally, apoptosis, ACD, and programmed necrosis are closely related to tumor growth, while anoikis and entosis are mainly correlated to tumor metastasis. As reviewed by Niu et al13, AR might function as a stimulator and as a suppressor in PCa cell growth and metastasis, respectively. Based on differential AR roles in tumor progression and metastasis, we summarized all 5 types of cell death mediated by AR as either beneficial or harmful in PCa progression.

Three types of cell death (apoptosis, ACD, and programmed necrosis), especially apoptosis, might play predominant roles in controlling the amount os PCa cell numbers. In PCa, AR could protect cells from apoptosis, ACD and programmed necrosis in most androgen sensitive PCa cells that would result in promotion of PCa growth. However, in some androgen-insensitive PCa cell lines154, AR might function as an apoptosis promoter instead of survival protector. This phenomenon could partly explain why ADT does not work well in castration-resistant PCa. After an early success to suppress PCa growth, ADT eventually fails, and might lead to tumor re-growth during the castration resistant stage, due to AR signaling blockage that may not be sufficient to lead to all types of PCa cell deaths.

Interestingly, two other kinds of cell death (anoikis and entosis), which were induced by detachment from ECM, are closely related to tumor metastasis. AR enhanced anoikis and entosis through different pathways, but both might lead to metastasis inhibition, consistent with AR suppressor roles in PCa metastasis13.

In summary, in PCa, androgen/AR signaling is one of the most important mechanisms that could regulate death induction and death resistance at the same time. Clear dissection of how AR modulates each type of cell death will help us to fight PCa more effecively.

5. New PCa therapies based on the opposite AR roles in different types of cell deaths

5.1 Challenge to current ADT

As mentioned above, androgen/AR signaling not only protected PCa cells from cell deaths including apoptosis, ACD and programmed necrosis, it also differentially modulated cell proliferation in PCa, suggesting it will be extremely difficult to apply a simple therapy, for example the current ADT, to systematically reduce androgen or prevent androgens binding to AR in every cell to suppress PCa progression. Furthermore, considering anoikis was closely linked to the progression of EMT106, which plays important roles in PCa metastasis, targeting anoikis has been indeed regarded as a strong therapeutic approach to battle metastatic PCa113. One may speculate that blocking of anoikis by ADT may then lead to the undesirable increase of metastases. Similar concerns also occurred in the entosis that was induced under the same condition as anoikis116 and it may also be speculated that ADT increased entosis might lead to enhanced PCa metastases.

Taken together, because of dual and opposite roles of AR in PCa proliferation, cell death and metastasis, it is necessary to re-consider whether the ADT that is currently used to treat PCa is safe and effective.

5.2 Combination therapy of ADT with inhibitor(s) of or interruption of AR-mediated cell death signaling pathways

The traditional ADT will block androgen/AR signaling and results in enhancement of cell deaths including apoptosis, ACD and programmed necrosis of PCa. However, it may also suppress other types of cell deaths, including anoikis and entosis, and might lead to increased metastases. This could be one of the reasons why the current ADT fails. Therefore, we need to develop a therapy combining the current ADT using the anti-androgen/AR drugs with a strategy that can block metastases that might be caused by these drugs-induced anoikis and entosis.

For the strategy to block the ADT drugs induced-anoikis, Platycodin D can be considered as a potential new therapy to battle PCa. AR could increase anoikis through suppression of the phosphorylation/activation of p3854. Platycodin D, which activates p38 MAPK signaling, has been used to induce anoikis in different human cancer cells115, 155. Therefore, ADT with Platycodin D to activate p38 could be a potential approach to block the ADT drugs induced-anoikis. Meanwhile, for the strategy to block the ADT with anti-androgen treatment induced-entosis, blocking with the RhoA/ROCK activator (such as RhoGEF2) could be considered since it was demonstrated that AR could enhance the RhoA/ROCK pathway that resulted in increased entosis65.

6. Conclusion and future prospects

The main current therapy for PCa (ADT with anti-androgens treatment) to reduce or prevent androgens binding to AR has been proven successful in some ways. However, these efforts eventually fail leading to a more advanced stage of PCa and this may be partially due to the dual yet opposite roles of AR in different types of cell death. Therefore, we may need to develop a therapy combining the current ADT treatment with the anti-anoikis and/or anti-entosis agents to fight the PCa. Alternatively, the recently developed AR degradation enhancer, ASC–J9® has been proven to suppress PCa in selective cells effectively156, 157. These types of combination therapies may be developed to better battle PCa in the future.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: NIH Grants (CA127300 and CA156700), Taiwan Department of Health Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence Grant DOH99-TD-B-111-004 (China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan), and National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB518304).

Footnotes

Disclosure summary: ASC–J9® was patented by the University of Rochester, the University of North Carolina, and AndroScience, and then licensed to AndroScience. Both the University of Rochester and C.C. own royalties and equity in AndroScience

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brawley OW. Trends in prostate cancer in the United States. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 2012;2012:152–6. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowe SW, Cepero E, Evan G. Intrinsic tumour suppression. Nature. 2004;432:307–15. doi: 10.1038/nature03098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams JM, Cory S. The Bcl-2 apoptotic switch in cancer development and therapy. Oncogene. 2007;26:1324–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams GT. Programmed cell death: apoptosis and oncogenesis. Cell. 1991;65:1097–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90002-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnstone RW, Ruefli AA, Lowe SW. Apoptosis: a link between cancer genetics and chemotherapy. Cell. 2002;108:153–64. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang CS, Kokontis J, Liao ST. Molecular cloning of human and rat complementary DNA encoding androgen receptors. Science. 1988;240:324–6. doi: 10.1126/science.3353726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenster G. The role of the androgen receptor in the development and progression of prostate cancer. Seminars in oncology. 1999;26:407–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinkmann AO, Blok LJ, de Ruiter PE, Doesburg P, Steketee K, Berrevoets CA, et al. Mechanisms of androgen receptor activation and function. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 1999;69:307–13. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(99)00049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang C, Saltzman A, Yeh S, Young W, Keller E, Lee HJ, et al. Androgen receptor: an overview. Critical reviews in eukaryotic gene expression. 1995;5:97–125. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v5.i2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Launoit Y, Veilleux R, Dufour M, Simard J, Labrie F. Characteristics of the biphasic action of androgens and of the potent antiproliferative effects of the new pure antiestrogen EM-139 on cell cycle kinetic parameters in LNCaP human prostatic cancer cells. Cancer research. 1991;51:5165–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huggins C, Hodges CV. Studies on prostatic cancer. I. The effect of castration, of estrogen and androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 1972;22:232–40. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.22.4.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niu Y, Chang TM, Yeh S, Ma WL, Wang YZ, Chang C. Differential androgen receptor signals in different cells explain why androgen-deprivation therapy of prostate cancer fails. Oncogene. 2010;29:3593–604. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singer EA, Golijanin DJ, Messing EM. Androgen deprivation therapy for advanced prostate cancer: why does it fail and can its effects be prolonged? The Canadian journal of urology. 2008;15:4381–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeh S, Niu Y, Miyamoto H, Chang T, Chang C. Differential Roles of Androgen Receptor in Prostate Development and Cancer Progression. In: Mohler J, Tindall D, editors. Androgen Action in Prostate Cancer. Springer US; 2009. pp. 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denis LJ, Griffiths K. Endocrine treatment in prostate cancer. Seminars in surgical oncology. 2000;18:52–74. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(200001/02)18:1<52::aid-ssu8>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisenberger MA, Blumenstein BA, Crawford ED, Miller G, McLeod DG, Loehrer PJ, et al. Bilateral orchiectomy with or without flutamide for metastatic prostate cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 1998;339:1036–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroder F, Crawford ED, Axcrona K, Payne H, Keane TE. Androgen deprivation therapy: past, present and future. BJU international. 2012;109 (Suppl 6):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pagliarulo V, Bracarda S, Eisenberger MA, Mottet N, Schroder FH, Sternberg CN, et al. Contemporary role of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. European urology. 2012;61:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niu Y, Altuwaijri S, Yeh S, Lai KP, Yu S, Chuang KH, et al. Targeting the stromal androgen receptor in primary prostate tumors at earlier stages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:12188–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804701105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niu Y, Altuwaijri S, Lai KP, Wu CT, Ricke WA, Messing EM, et al. Androgen receptor is a tumor suppressor and proliferator in prostate cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:12182–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804700105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Y, Wang BE, Leong KG, Yue P, Li L, Jhunjhunwala S, et al. Androgen deprivation causes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the prostate: implications for androgen-deprivation therapy. Cancer research. 2012;72:527–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Bokhoven A, Varella-Garcia M, Korch C, Johannes WU, Smith EE, Miller HL, et al. Molecular characterization of human prostate carcinoma cell lines. The Prostate. 2003;57:205–25. doi: 10.1002/pros.10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Leenders GJLH, Schalken JA. Epithelial cell differentiation in the human prostate epithelium: Implications for the pathogenesis and therapy of prostate cancer. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2003;46:3–10. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(03)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonkhoff H, Stein U, Remberger K. The proliferative function of basal cells in the normal and hyperplastic human prostate. The Prostate. 1994;24:114–8. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Litvinov IV, De Marzo AM, Isaacs JT. Is the Achilles’ heel for prostate cancer therapy a gain of function in androgen receptor signaling? The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2003;88:2972–82. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-022038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tokar EJ, Ancrile BB, Cunha GR, Webber MM. Stem/progenitor and intermediate cell types and the origin of human prostate cancer. Differentiation; research in biological diversity. 2005;73:463–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2005.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horoszewicz JS, Leong SS, Kawinski E, Karr JP, Rosenthal H, Chu TM, et al. LNCaP model of human prostatic carcinoma. Cancer research. 1983;43:1809–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horoszewicz JS, Leong SS, Chu TM, Wajsman ZL, Friedman M, Papsidero L, et al. The LNCaP cell line--a new model for studies on human prostatic carcinoma. Progress in clinical and biological research. 1980;37:115–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eder IE, Culig Z, Ramoner R, Thurnher M, Putz T, Nessler-Menardi C, et al. Inhibition of LncaP prostate cancer cells by means of androgen receptor antisense oligonucleotides. Cancer gene therapy. 2000;7:997–1007. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haag P, Bektic J, Bartsch G, Klocker H, Eder IE. Androgen receptor down regulation by small interference RNA induces cell growth inhibition in androgen sensitive as well as in androgen independent prostate cancer cells. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2005;96:251–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liao X, Tang S, Thrasher JB, Griebling TL, Li B. Small-interfering RNA-induced androgen receptor silencing leads to apoptotic cell death in prostate cancer. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2005;4:505–15. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagabhushan M, Miller CM, Pretlow TP, Giaconia JM, Edgehouse NL, Schwartz S, et al. CWR22: the first human prostate cancer xenograft with strongly androgen-dependent and relapsed strains both in vivo and in soft agar. Cancer research. 1996;56:3042–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li TH, Zhao H, Peng Y, Beliakoff J, Brooks JD, Sun Z. A promoting role of androgen receptor in androgen-sensitive and -insensitive prostate cancer cells. Nucleic acids research. 2007;35:2767–76. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaighn ME, Narayan KS, Ohnuki Y, Lechner JF, Jones LW. Establishment and characterization of a human prostatic carcinoma cell line (PC-3) Investigative urology. 1979;17:16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Litvinov IV, Chang C, Isaacs JT. Molecular characterization of the commonly used human androgen receptor expression vector, pSG5-AR. The Prostate. 2004;58:319–24. doi: 10.1002/pros.20027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Litvinov IV, Antony L, Dalrymple SL, Becker R, Cheng L, Isaacs JT. PC3, but not DU145, human prostate cancer cells retain the coregulators required for tumor suppressor ability of androgen receptor. The Prostate. 2006;66:1329–38. doi: 10.1002/pros.20483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SO, Tian J, Huang CK, Ma Z, Lai KP, Hsiao H, et al. Suppressor role of androgen receptor in proliferation of prostate basal epithelial and progenitor cells. The Journal of endocrinology. 2012;213:173–82. doi: 10.1530/JOE-11-0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cunha GR, Hayward SW, Wang YZ, Ricke WA. Role of the stromal microenvironment in carcinogenesis of the prostate. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2003;107:1–10. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhowmick NA, Moses HL. Tumor-stroma interactions. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2005;15:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Condon MS. The role of the stromal microenvironment in prostate cancer. Seminars in cancer biology. 2005;15:132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Halin S, Hammarsten P, Wikstrom P, Bergh A. Androgen-insensitive prostate cancer cells transiently respond to castration treatment when growing in an androgen-dependent prostate environment. The Prostate. 2007;67:370–7. doi: 10.1002/pros.20473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gleave M, Hsieh JT, Gao CA, von Eschenbach AC, Chung LW. Acceleration of human prostate cancer growth in vivo by factors produced by prostate and bone fibroblasts. Cancer research. 1991;51:3753–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai KP, Yamashita S, Vitkus S, Shyr CR, Yeh S, Chang C. Suppressed prostate epithelial development with impaired branching morphogenesis in mice lacking stromal fibromuscular androgen receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:52–66. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaarbo M, Klokk TI, Saatcioglu F. Androgen signaling and its interactions with other signaling pathways in prostate cancer. BioEssays: news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2007;29:1227–38. doi: 10.1002/bies.20676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin Y, Kokontis J, Tang F, Godfrey B, Liao S, Lin A, et al. Androgen and its receptor promote Bax-mediated apoptosis. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26:1908–16. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.5.1908-1916.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang F, Kokontis J, Lin Y, Liao S, Lin A, Xiang J. Androgen via p21 inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced JNK activation and apoptosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:32353–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhatnagar N, Li X, Padi SK, Zhang Q, Tang MS, Guo B. Downregulation of miR-205 and miR-31 confers resistance to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Cell death & disease. 2010;1:e105. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flourakis M, Lehen’kyi V, Beck B, Raphael M, Vandenberghe M, Abeele FV, et al. Orai1 contributes to the establishment of an apoptosis-resistant phenotype in prostate cancer cells. Cell death & disease. 2010;1:e75. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bennett HL, Fleming JT, O’Prey J, Ryan KM, Leung HY. Androgens modulate autophagy and cell death via regulation of the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone glucose-regulated protein 78/BiP in prostate cancer cells. Cell death & disease. 2010;1:e72. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rokhlin OW, Taghiyev AF, Guseva NV, Glover RA, Chumakov PM, Kravchenko JE, et al. Androgen regulates apoptosis induced by TNFR family ligands via multiple signaling pathways in LNCaP. Oncogene. 2005;24:6773–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang Q, Yeh S, Wang X, Xu D, Zhang Q, Wen X, et al. Targeting androgen receptor leads to suppression of prostate cancer via induction of autophagy. The Journal of urology. 2012;188:1361–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma WL, Hsu CL, Yeh CC, Wu MH, Huang CK, Jeng LB, et al. Hepatic androgen receptor suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through modulation of cell migration and anoikis. Hepatology. 2012;56:176–85. doi: 10.1002/hep.25644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhuiyan MM, Li Y, Banerjee S, Ahmed F, Wang Z, Ali S, et al. Down-regulation of androgen receptor by 3,3′-diindolylmethane contributes to inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis in both hormone-sensitive LNCaP and insensitive C4–2B prostate cancer cells. Cancer research. 2006;66:10064–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oh SJ, Erb HH, Hobisch A, Santer FR, Culig Z. Sorafenib decreases proliferation and induces apoptosis of prostate cancer cells by inhibition of the androgen receptor and Akt signaling pathways. Endocrine-related cancer. 2012;19:305–19. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang Y, Li X, Liu Z, Simoneau AR, Xie J, Zi X. Flavokawain B, a kava chalcone, induces apoptosis via up-regulation of death-receptor 5 and Bim expression in androgen receptor negative, hormonal refractory prostate cancer cell lines and reduces tumor growth. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2010;127:1758–68. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Han H, Qiu L, Wang X, Qiu F, Wong Y, Yao X. Physalins A and B inhibit androgen-independent prostate cancer cell growth through activation of cell apoptosis and downregulation of androgen receptor expression. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin. 2011;34:1584–8. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Abrams JM, Alnemri ES, Baehrecke EH, Blagosklonny MV, et al. Molecular definitions of cell death subroutines: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2012. Cell death and differentiation. 2012;19:107–20. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lewis EM, Wilkinson AS, Jackson JS, Mehra R, Varambally S, Chinnaiyan AM, et al. The enzymatic activity of apoptosis-inducing factor supports energy metabolism benefiting the growth and invasiveness of advanced prostate cancer cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:43862–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.407650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carraway RE, Dobner PR. Zinc pyrithione induces ERK- and PKC-dependent necrosis distinct from TPEN-induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012;1823:544–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu Z. The initial observation that AR inhibits prostate cancer cell necrosis. Tianjin Medical University; Tianjin, China: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ouyang DY, Xu LH, He XH, Zhang YT, Zeng LH, Cai JY, et al. Autophagy is differentially induced in prostate cancer LNCaP, DU145 and PC-3 cells via distinct splicing profiles of ATG5. Autophagy. 2013;9:20–32. doi: 10.4161/auto.22397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giannoni E, Fiaschi T, Ramponi G, Chiarugi P. Redox regulation of anoikis resistance of metastatic prostate cancer cells: key role for Src and EGFR-mediated pro-survival signals. Oncogene. 2009;28:2074–86. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wen S, Shang Z, Zhu S, Chang C, Niu Y. The Prostate. 2013. Androgen receptor enhances entosis, a non-apoptotic cell death, through modulation of Rho/ROCK pathway in prostate cancer cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frezza M, Yang H, Dou QP. Modulation of the tumor cell death pathway by androgen receptor in response to cytotoxic stimuli. Journal of cellular physiology. 2011;226:2731–9. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bennett HL, Stockley J, Fleming JT, Mandal R, O’Prey J, Ryan KM, et al. Does androgen-ablation therapy (AAT) associated autophagy have a pro-survival effect in LNCaP human prostate cancer cells? BJU international. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin TH, Lee SO, Niu Y, Xu D, Liang L, Li L, et al. Differential Androgen Deprivation Therapies with Anti-androgens Casodex/Bicalutamide or MDV3100/Enzalutamide versus Anti-androgen Receptor ASC-J9(R) Lead to Promotion versus Suppression of Prostate Cancer Metastasis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:19359–69. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.477216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. British journal of cancer. 1972;26:239–57. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fulda S, Debatin KM. Extrinsic versus intrinsic apoptosis pathways in anticancer chemotherapy. Oncogene. 2006;25:4798–811. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fulda S, Debatin KM. Modulation of apoptosis signaling for cancer therapy. Archivum immunologiae et therapiae experimentalis. 2006;54:173–5. doi: 10.1007/s00005-006-0019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pipan N, Sterle M. Cytochemical analysis of organelle degradation in phagosomes and apoptotic cells of the mucoid epithelium of mice. Histochemistry. 1979;59:225–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00495670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thornberry NA, Bull HG, Calaycay JR, Chapman KT, Howard AD, Kostura MJ, et al. A novel heterodimeric cysteine protease is required for interleukin-1 beta processing in monocytes. Nature. 1992;356:768–74. doi: 10.1038/356768a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thornberry NA, Lazebnik Y. Caspases: Enemies within. Science. 1998;281(5381):5. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Degterev A, Boyce M, Yuan J. A decade of caspases. Oncogene. 2003;22:8543–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–6. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407(6805):7. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cory S, Adams JM. The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nature reviews Cancer. 2002;2:647–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Godfrey B, Lin Y, Larson J, Haferkamp B, Xiang J. Proteasomal degradation unleashes the pro-death activity of androgen receptor. Cell research. 2010;20:1138–47. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li RJ, Qiu SD, Wang HX, Tian H, Wang LR, Huo YW. Androgen receptor: a new player associated with apoptosis and proliferation of pancreatic beta-cell in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Apoptosis: an international journal on programmed cell death. 2008;13:959–71. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Williams GT, Smith CA. Molecular regulation of apoptosis: genetic controls on cell death. Cell. 1993;74:777–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matsumoto T, Sakari M, Okada M, Yokoyama A, Takahashi S, Kouzmenko A, et al. The androgen receptor in health and disease. Annual review of physiology. 2013;75:201–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gorospe M, Cirielli C, Wang X, Seth P, Capogrossi MC, Holbrook NJ. p21(Waf1/Cip1) protects against p53-mediated apoptosis of human melanoma cells. Oncogene. 1997;14:929–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Asada M, Yamada T, Ichijo H, Delia D, Miyazono K, Fukumuro K, et al. Apoptosis inhibitory activity of cytoplasmic p21Cip1/WAF1 in monocytic differentiation. EMBO J. 1999;18(5):12. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lu S, Liu M, Epner DE, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ. Androgen regulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 gene through an androgen response element in the proximal promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:376–84. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.3.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kimura K, Markowski M, Bowen C, Gelmann EP. Androgen blocks apoptosis of hormone-dependent prostate cancer cells. Cancer research. 2001;61:5611–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kadowaki Y, Chari NS, Teo AE, Hashi A, Spurgers KB, McDonnell TJ. PI3 Kinase inhibition on TRAIL-induced apoptosis correlates with androgen-sensitivity and p21 expression in prostate cancer cells. Apoptosis: an international journal on programmed cell death. 2011;16:627–35. doi: 10.1007/s10495-011-0591-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sun M, Yang L, Feldman RI, Sun XM, Bhalla KN, Jove R, et al. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway by androgen through interaction of p85alpha, androgen receptor, and Src. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:42992–3000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang L, Xie S, Jamaluddin MS, Altuwaijri S, Ni J, Kim E, et al. Induction of androgen receptor expression by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt downstream substrate, FOXO3a, and their roles in apoptosis of LNCaP prostate cancer cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:33558–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nguyen TV, Yao M, Pike CJ. Androgens activate mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling: role in neuroprotection. Journal of neurochemistry. 2005;94:1639–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Simoes VL, Alves MG, Martins AD, Dias TR, Rato L, Socorro S, et al. Regulation of apoptotic signaling pathways by 5alpha-dihydrotestosterone and 17beta-estradiol in immature rat Sertoli cells. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2013;135:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brooke GN, Culley RL, Dart DA, Mann DJ, Gaughan L, McCracken SR, et al. FUS/TLS is a novel mediator of androgen-dependent cell-cycle progression and prostate cancer growth. Cancer research. 2011;71:914–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Diallo JS, Peant B, Lessard L, Delvoye N, Le Page C, Mes-Masson AM, et al. An androgen-independent androgen receptor function protects from inositol hexakisphosphate toxicity in the PC3/PC3(AR) prostate cancer cell lines. The Prostate. 2006;66:1245–56. doi: 10.1002/pros.20455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yang H, Murthy S, Sarkar FH, Sheng S, Reddy GP, Dou QP. Calpain-mediated androgen receptor breakdown in apoptotic prostate cancer cells. Journal of cellular physiology. 2008;217:569–76. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lin Y, Lu Z, Kokontis J, Xiang J. Androgen receptor primes prostate cancer cells to apoptosis through down-regulation of basal p21 expression. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.10.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Risek B, Bilski P, Rice AB, Schrader WT. Androgen receptor-mediated apoptosis is regulated by photoactivatable androgen receptor ligands. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:2099–115. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.LaFevre-Bernt MA, Ellerby LM. Kennedy’s disease. Phosphorylation of the polyglutamine-expanded form of androgen receptor regulates its cleavage by caspase-3 and enhances cell death. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:34918–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Young JE, Garden GA, Martinez RA, Tanaka F, Sandoval CM, Smith AC, et al. Polyglutamine-expanded androgen receptor truncation fragments activate a Bax-dependent apoptotic cascade mediated by DP5/Hrk. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:1987–97. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4072-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hatzoglou A, Kampa M, Kogia C, Charalampopoulos I, Theodoropoulos PA, Anezinis P, et al. Membrane androgen receptor activation induces apoptotic regression of human prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2005;90:893–903. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Papadopoulou N, Charalampopoulos I, Anagnostopoulou V, Konstantinidis G, Foller M, Gravanis A, et al. Membrane androgen receptor activation triggers down-regulation of PI-3K/Akt/NF-kappaB activity and induces apoptotic responses via Bad, FasL and caspase-3 in DU145 prostate cancer cells. Molecular cancer. 2008;7:88. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-7-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Adams JC, Watt FM. Regulation of development and differentiation by the extracellular matrix. Development. 1993;117:1183–98. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Blau HM, Baltimore D. Differentiation requires continuous regulation. The Journal of cell biology. 1991;112:781–3. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.5.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Takeuchi T, Suzuki M, Kumagai J, Kamijo T, Sakai M, Kitamura T. Extracellular matrix dermatopontin modulates prostate cell growth in vivo. The Journal of endocrinology. 2006;190:351–61. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ruoslahti E, Reed JC. Anchorage dependence, integrins, and apoptosis. Cell. 1994;77:477–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Frisch SM, Francis H. Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. The Journal of cell biology. 1994;124:619–26. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rennebeck G, Martelli M, Kyprianou N. Anoikis and survival connections in the tumor microenvironment: is there a role in prostate cancer metastasis? Cancer research. 2005;65:11230–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Keledjian K, Kyprianou N. Anoikis induction by quinazoline based alpha 1-adrenoceptor antagonists in prostate cancer cells: antagonistic effect of bcl-2. The Journal of urology. 2003;169:1150–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000042453.12079.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Garrison JB, Kyprianou N. Novel targeting of apoptosis pathways for prostate cancer therapy. Current cancer drug targets. 2004;4:85–95. doi: 10.2174/1568009043481623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Frisch SM, Ruoslahti E. Integrins and anoikis. Current opinion in cell biology. 1997;9:701–6. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Frisch SM, Screaton RA. Anoikis mechanisms. Current opinion in cell biology. 2001;13:555–62. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Reginato MJ, Mills KR, Paulus JK, Lynch DK, Sgroi DC, Debnath J, et al. Integrins and EGFR coordinately regulate the pro-apoptotic protein Bim to prevent anoikis. Nature cell biology. 2003;5:733–40. doi: 10.1038/ncb1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mailleux AA, Overholtzer M, Schmelzle T, Bouillet P, Strasser A, Brugge JS. BIM regulates apoptosis during mammary ductal morphogenesis, and its absence reveals alternative cell death mechanisms. Developmental cell. 2007;12:221–34. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sakamoto S, Kyprianou N. Targeting anoikis resistance in prostate cancer metastasis. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2010;31:205–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wen HC, Avivar-Valderas A, Sosa MS, Girnius N, Farias EF, Davis RJ, et al. p38alpha Signaling Induces Anoikis and Lumen Formation During Mammary Morphogenesis. Science signaling. 2011;4:ra34. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chun J, Joo EJ, Kang M, Kim YS. Platycodin D induces anoikis and caspase-mediated apoptosis via p38 MAPK in AGS human gastric cancer cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2013;114:456–70. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Overholtzer M, Mailleux AA, Mouneimne G, Normand G, Schnitt SJ, King RW, et al. A nonapoptotic cell death process, entosis, that occurs by cell-in-cell invasion. Cell. 2007;131:966–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.White E. Entosis: it’s a cell-eat-cell world. Cell. 2007;131:840–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ohsaki H, Haba R, Matsunaga T, Nakamura M, Kiyomoto H, Hirakawa E. ‘Cannibalism’ (cell phagocytosis) does not differentiate reactive renal tubular cells from urothelial carcinoma cells. Cytopathology: official journal of the British Society for Clinical Cytology. 2009;20:224–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2009.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Xia P, Wang S, Guo Z, Yao X. Emperipolesis, entosis and beyond: dance with fate. Cell research. 2008;18:705–7. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yang YQ, Li JC. Progress of research in cell-in-cell phenomena. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2012;295:372–7. doi: 10.1002/ar.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Krajcovic M, Johnson NB, Sun Q, Normand G, Hoover N, Yao E, et al. A non-genetic route to aneuploidy in human cancers. Nature cell biology. 2011;13:324–30. doi: 10.1038/ncb2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Janssen A, Medema RH. Entosis: aneuploidy by invasion. Nature cell biology. 2011;13:199–201. doi: 10.1038/ncb0311-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Fiorentini C, Falzano L, Fabbri A, Stringaro A, Logozzi M, Travaglione S, et al. Activation of rho GTPases by cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 induces macropinocytosis and scavenging activity in epithelial cells. Molecular biology of the cell. 2001;12:2061–73. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.7.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lai Y, Lim D, Tan PH, Leung TK, Yip GW, Bay BH. Silencing the Metallothionein-2A gene induces entosis in adherent MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2010;293:1685–91. doi: 10.1002/ar.21215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wan Q, Liu J, Zheng Z, Zhu H, Chu X, Dong Z, et al. Regulation of myosin activation during cell-cell contact formation by Par3-Lgl antagonism: entosis without matrix detachment. Molecular biology of the cell. 2012;23:2076–91. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-11-0940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Laster SM, Wood JG, Gooding LR. Tumor necrosis factor can induce both apoptic and necrotic forms of cell lysis. J Immunol. 1988;141:2629–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, Genga R, Ray TD, Guildford M, et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell. 2009;137:1112–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hitomi J, Christofferson DE, Ng A, Yao J, Degterev A, Xavier RJ, et al. Identification of a molecular signaling network that regulates a cellular necrotic cell death pathway. Cell. 2008;135:1311–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zhang DW, Shao J, Lin J, Zhang N, Lu BJ, Lin SC, et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science. 2009;325:332–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1172308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Degterev A, Huang Z, Boyce M, Li Y, Jagtap P, Mizushima N, et al. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nature chemical biology. 2005;1:112–9. doi: 10.1038/nchembio711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zong WX, Ditsworth D, Bauer DE, Wang ZQ, Thompson CB. Alkylating DNA damage stimulates a regulated form of necrotic cell death. Genes & development. 2004;18:1272–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.1199904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bano D, Young KW, Guerin CJ, Lefeuvre R, Rothwell NJ, Naldini L, et al. Cleavage of the plasma membrane Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in excitotoxicity. Cell. 2005;120:275–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Vercammen D, Brouckaert G, Denecker G, Van de Craen M, Declercq W, Fiers W, et al. Dual signaling of the Fas receptor: initiation of both apoptotic and necrotic cell death pathways. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;188:919–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Holler N, Zaru R, Micheau O, Thome M, Attinger A, Valitutti S, et al. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nature immunology. 2000;1:489–95. doi: 10.1038/82732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Boya P, Kroemer G. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization in cell death. Oncogene. 2008;27:6434–51. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Brenner C. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in cell death. Physiological reviews. 2007;87:99–163. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Goossens V, Stange G, Moens K, Pipeleers D, Grooten J. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor-induced, mitochondria- and reactive oxygen species-dependent cell death by the electron flux through the electron transport chain complex I. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 1999;1:285–95. doi: 10.1089/ars.1999.1.3-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kim YS, Morgan MJ, Choksi S, Liu ZG. TNF-induced activation of the Nox1 NADPH oxidase and its role in the induction of necrotic cell death. Molecular cell. 2007;26:675–87. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Yazdanpanah B, Wiegmann K, Tchikov V, Krut O, Pongratz C, Schramm M, et al. Riboflavin kinase couples TNF receptor 1 to NADPH oxidase. Nature. 2009;460:1159–63. doi: 10.1038/nature08206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Monus Z, Laszlo FA. Cyproterone acetate-promoted prevention of renal cortical necrosis following testosterone and vasopressin administration. British journal of experimental pathology. 1979;60:72–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Sun HZ, Yang TW, Zang WJ, Wu SF. Dehydroepiandrosterone-induced proliferation of prostatic epithelial cell is mediated by NFKB via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. The Journal of endocrinology. 2010;204:311–8. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.De Duve C, Wattiaux R. Functions of lysosomes. Annual review of physiology. 1966;28:435–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.28.030166.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nature cell biology. 2010;12:814–22. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Montie HL, Cho MS, Holder L, Liu Y, Tsvetkov AS, Finkbeiner S, et al. Cytoplasmic retention of polyglutamine-expanded androgen receptor ameliorates disease via autophagy in a mouse model of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Human molecular genetics. 2009;18:1937–50. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Florey O, Kim SE, Sandoval CP, Haynes CM, Overholtzer M. Autophagy machinery mediates macroendocytic processing and entotic cell death by targeting single membranes. Nature cell biology. 2011;13:1335–43. doi: 10.1038/ncb2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Developmental cell. 2004;6:463–77. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Liu B, Cheng Y, Liu Q, Bao JK, Yang JM. Autophagic pathways as new targets for cancer drug development. Acta pharmacologica Sinica. 2010;31:1154–64. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Liang C, Jung JU. Autophagy genes as tumor suppressors. Current opinion in cell biology. 2010;22:226–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Parikh A, Childress C, Deitrick K, Lin Q, Rukstalis D, Yang W. Statin-induced autophagy by inhibition of geranylgeranyl biosynthesis in prostate cancer PC3 cells. The Prostate. 2010;70:971–81. doi: 10.1002/pros.21131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Suh Y, Afaq F, Khan N, Johnson JJ, Khusro FH, Mukhtar H. Fisetin induces autophagic cell death through suppression of mTOR signaling pathway in prostate cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1424–33. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Toepfer N, Childress C, Parikh A, Rukstalis D, Yang W. Atorvastatin induces autophagy in prostate cancer PC3 cells through activation of LC3 transcription. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12:691–9. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.8.15978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Kung HJ. Targeting tyrosine kinases and autophagy in prostate cancer. Hormones & cancer. 2011;2:38–46. doi: 10.1007/s12672-010-0053-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Chuu CP, Kokontis JM, Hiipakka RA, Fukuchi J, Lin HP, Lin CY, et al. Androgen suppresses proliferation of castration-resistant LNCaP 104-R2 prostate cancer cells through androgen receptor, Skp2, and c-Myc. Cancer science. 2011;102:2022–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Park MT, Choi JA, Kim MJ, Um HD, Bae S, Kang CM, et al. Suppression of extracellular signal-related kinase and activation of p38 MAPK are two critical events leading to caspase-8- and mitochondria-mediated cell death in phytosphingosine-treated human cancer cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:50624–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Yang Z, Chang YJ, Yu IC, Yeh S, Wu CC, Miyamoto H, et al. ASC-J9 ameliorates spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy phenotype via degradation of androgen receptor. Nature medicine. 2007;13:348–53. doi: 10.1038/nm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]