Abstract

The treatment of uncomplicated osteoma consists of an en bloc resection, or curettage, of the tumor, followed by cranioplasty. Here, we present a case report of a patient treated for a parietal osteoma, followed by a calcium phosphate cranioplasty, with early resorption after 3 months, which was presented by a sinking flap above the resection area. This case suggests that synthetic cranioplasty should be preferred, even in small skull-gap areas.

Keywords: cranioplasty, bone cement, osteoma, calcium phosphate, resorption

Introduction

Osteoma are benign bone tumors with slow growth from the outer table more common than from the inner table, and occurring more often in women than men. The symptoms include deformity; local pain or headaches can also occur. Osteoma that generate mechanical complications, such as ostial obstruction, facial, and cranial deformity or proptosis, are indications for surgery. The treatment of an uncomplicated osteoma consists of en bloc resection, or curettage, of the tumor followed by cranioplasty (CP). There are many options for performing CP. This paper reports a case in which calcium phosphate bone cement was used in a relatively small skull-gap. Early resorption resulted in a cosmetically suboptimal result.

Case report

A 24-year-old man noticed a slow growing mass over the left parietal region of his skull. Radiological studies suggested an osteoma. After 3 years of follow-up, the lesion became larger, with an irregular surface. Surgical resection was then indicated.

The procedure consisted of an open craniectomy. The bone around the tumor was removed using a pneumatic craniotome, and by drilling away bony matrix over the sagittal sinus bone to the sagittal suture. After complete tumor removal, CP was performed using calcium phosphate bone cement (Bone Plast® Bone Void Filler, Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA), covering the entire bone gap (22 cm2), and above the inner table close to the sagittal sinus. Pathologic analysis suggested osteoma with low density of Haversian canals and mineralization, without signs of malignancy.

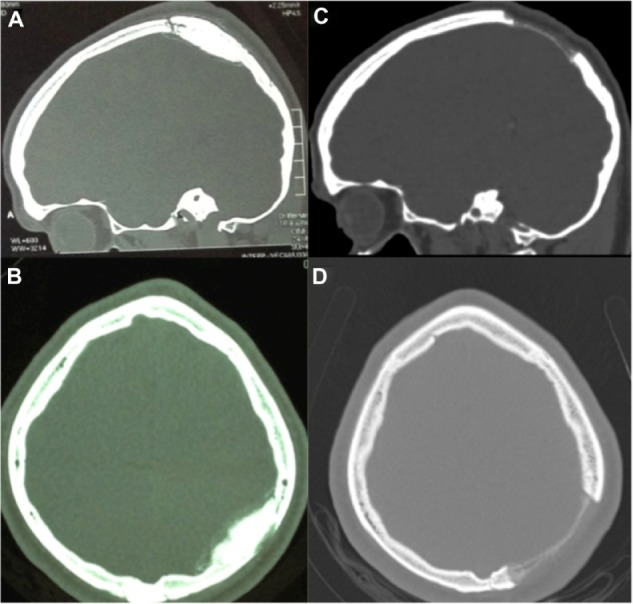

One month after the procedure, the patient noticed that the CP was not consolidated. He felt the flap moving while performing the Valsalva maneuver. Radiological investigation was performed and the area covered by the CP was not consolidated to the bone, and fragmentation could be observed (Figure 1A and B). After 3 months, the patient noticed a sunken area of scalp. Radiological investigation reported that the patient had absorbed the calcium phosphate bone cement (Figure 1C and D).

Figure 1.

Cranioplasty status.

Notes: (A and B) Status post-cranioplasty with calcium-phosphate bone cement. (Note fragmentation and fusion failure.) (C and D) Cranioplasty resorption after 3 months.

Discussion

It is known that in long-term follow-up (5 years), there is a 25% chance of partial CP resorption,1 but, there is no case of early calcium phosphate cement CP resorption to be found in the literature. Early experiments in animal models reported significant replacement of cement by bone. But several authors later documented that replacement by native bone is limited to the periphery of the implanted cement.2 Because the calcium phosphate cement is never fully replaced by bone, it will be at risk for complications, such as documented here.

Aseptic bone flap resorption is a known long-term complication after autologous CP, and is more common in young skulls and those with traumatic, and multiple fractures, and in CP performed within a two-month interval.3 Rates of resorption can vary from 40% to 47.1% of the cases.4

It is not recommended to use only calcium phosphate cement in large defects.1 Reconstruction of full-thickness cranial defects larger than 25 cm2 tended to produce worse outcomes.5 Complications associated with calcium phosphate cement are: infection (5%–20%), fragmentation, foreign body reaction, migration and/or seroma (11%), and need of secondary surgery for contour correction (1%).2,5 Patients exposed to radiation and patients with skull defects contiguous with the paranasal sinuses are more likely to have complications.1,2 Non-consolidation of CP to the bone, and fragmentation, may have contributed to the early CP resorption, before ossification.

Conclusion

This report suggests that calcium phosphate bone cement can be resorbed in a short time, before ossification. Even in small craniectomy gaps, other kinds of non-resorbable bone substitute may be considered.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Zins JE, Langevin CJ, Nasir S. Controversies in skull reconstruction. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:1755–1760. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181c34675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afifi AM, Gordon CR, Pryor LS, Sweeney W, Papay FA, Zins JE. Calcium phosphate cements in skull reconstruction: a meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1300–1309. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ead057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuss P, Vatter H, Oszvald A, et al. Bone flap resorption: risk factors for the development of a long-term complication following cranioplasty after decompressive craniectomy. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:91–95. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant GA, Jolley M, Ellenbogen RG, Roberts TS, Gruss JR, Loeser JD. Failure of autologous bone-assisted cranioplasty following decompressive craniectomy in children and adolescents. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:163–168. doi: 10.3171/ped.2004.100.2.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilardino MS, Cabiling DS, Bartlett SP. Long-term follow-up experience with carbonated calcium phosphate cement (Norian) for cranioplasty in children and adults. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:983–994. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318199f6ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]