Abstract

Purpose:

Information about the safety of herbal medicine often comes from case reports published in the medical literature, thus necessitating good quality reporting of these adverse events. The purpose of this study was to perform a systematic review of the comprehensiveness of reporting of published case reports of adverse events associated with herb use in the pediatric population.

Methods:

Electronic literature search included 7 databases and a manual search of retrieved articles from inception through 2010. We included published case reports and case series that reported an adverse event associated with exposure to an herbal product by children under the age of 18 years old. We used descriptive statistics. Based on the International Society of Epidemiology's “Guidelines for Submitting Adverse Events Reports for Publication,” we developed and assigned a guideline adherence score (0-17) to each case report.

Results:

Ninety-six unique journal papers were identified and represented 128 cases. Of the 128 cases, 37% occurred in children under 2 years old, 38% between the ages of 2 and 8 years old, and 23% between the ages of 9 and 18 years old. Twenty-nine percent of cases were the result of an intentional ingestion while 36% were from an unintentional ingestion. Fifty-two percent of cases documented the Latin binomial of the herb ingredients; 41% documented plant part. Thirty-two percent of the cases reported laboratory testing of the herb, 20% documented the manufacturer of the product, and 22% percent included an assessment of the potential concomitant therapies that could have been influential in the adverse events. Mean guideline adherence score was 12.5 (range 6-17).

Conclusions:

There is considerable need for improvement in reporting adverse events in children following herb use. Without better quality reporting, adverse event reports cannot be interpreted reliably and do not contribute in a meaningful way to guiding recommendations for medicinal herb use.

Key Words: Herbs, adverse events, pediatric, systematic review

摘要

目的:关于草药安全性的信息往 往来自医疗文献中发布的病例报 告,因而对这些不良事件进行高 质量的报告极为必要。本研究旨 在针对已发布的病例报告(对该 群体(儿童)使用草药相关的不 良事件的报告),就其全面性进 行系统性的审查。

方法:包括对 7 个数据库进行电 子文献搜索和对从 2010 年以来检 索到的文章进行手动搜索。我们 纳入了已发布的病例报告和病例 系列,它们报告了与年龄不满 18 周岁的儿童接触草药制品有关的 不良事件。我们使用了描述性的 统计数据。根据国际流行病学会 “针对准备对外发布的不良事件 报告的提交指导方针”,我们向 每个病例报告制定并分配了指导 方针的遵从性得分 (0-17)。

结果:96 篇独一无二的期刊论文 确认并展示了128 个病例。在这 128 个病例当中,37% 发生在不满 2 周岁的儿童当中,38% 介于 2 到 8 岁之间,23% 介于 9 到 18 岁之间。29% 的病例是有意识食物 摄入的结果,而 36% 来自无意识 的食物摄入。52% 的病例记录了草 药成分的拉丁二项式;41% 记录了 植物部分。32% 的病例报告了对草 药的实验室测试,20% 记录了产品 的制造商,22% 纳入了可能对不良 事件有影响的潜在伴随治疗的评 估。平均指导方针遵从性得分为 12.5(范围 6-17)。

结论:针对儿童使用草药后的不 良事件报告有很大的改进必要。 如果没有质量更好的报告,不良 事件报告将无法可靠地解释且不 会以有意义的方式对草药的使用 提供指导性建议。

SINOPSIS

Propósito:

La información sobre la seguridad de los productos fitoterapéuticos procede con frecuencia de informes de caso incluidos en publicaciones médicas, por lo que se necesita una notificación de buena calidad de estos acontecimientos adversos. El propósito de este estudio era realizar una revisión sistemática de la exhaustividad de notificación de los informes de caso publicados sobre acontecimientos adversos asociados con el uso de productos fitoterapéuticos en la población pediátrica.

Métodos:

La búsqueda de publicaciones electrónicas incluyó siete bases de datos y una búsqueda manual de los artículos recuperados desde el inicio hasta 2010. Se incluyeron informes de caso publicados y series de casos que notificaban un acontecimiento adverso asociado con la exposición a un producto fitoterapéutico de niños de menos de 18 años. Se utilizó la estadística descriptiva. Con base en las «Pautas para el envío de informes de acontecimientos adversos para su publicación» (Guidelines for Submitting Adverse Events Reports for Publication) de la Sociedad Internacional de Epidemiología (International Society of Epidemiology), se elaboró y asignó una puntuación de seguimiento de las pautas (de 0 a 17) a cada informe de caso.

Resultados:

Se identificaron 96 publicaciones únicas que represent-aban 128 casos. De ellos, el 37 % se produjo en niños menores de 2 años de edad, el 38 % en niños de entre 2 y 8 años de edad, y el 23 % entre las edades de 9 y 18 años. El 29 % de los casos fue resultado de la ingesta intencional, mientras que el 36 % lo fue de una ingesta no intencionada. El 52 % de los casos documentaba el nombre científico binominal en latín de los ingredientes del producto fitoterapéutico y el 41 % documentaba la parte de la planta. El 32 % de los casos notificaba pruebas de laboratorio del producto fitoterapéutico, el 20 % documentaba su fabricante y el 22 % incluía una evaluación de los posibles tratamientos concomitantes que podían haber influido en los acontecimientos adversos. La puntuación media de seguimiento de las pautas era de 12,5 (rango de 6 a 17).

Conclusiones:

Resulta bastante necesario mejorar la notificación de acontecimientos adversos en los niños después del uso de productos fitoterapéuticos. Sin notificaciones de mejor calidad, los informes de acontecimientos adversos no pueden interpretarse de manera fiable ni contribuyen de forma significativa a las recomendaciones de guía para el uso de productos fitoterapéuticos.

INTRODUCTION

In 2007, an estimated 12% of US children used complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), and 5% of children used biologically based therapies including herbs and dietary supplements.1 Little is known about pediatric herbal safety and whether details of herbal adverse events (AEs) are comprehensively reported in the literature.

Definitions vary, but in general an AE is an unintended, undesired, or harmful effect associated with the use of a medication, intervention, or dietary supplement.2 In terms of models of herbal adverse event surveillance, there are many ways that adverse event reports (AERs) are collected in children including case reports in journals, poison control centers, and other state and national government organizations (eg, Medwatch). For example, the California Poison Control Centers reported that of 828 dietary supplement—related AE exposure reports, more than half were among children.3

AERs are also reported in the indexed medical literature. Case reports often come in the form of letters to the editors, brief reports, or case reports from clinicians who can comment on the presentation of the patient and the treatment plan that was followed to address the event.4 Case reports may be a useful source of information about herbs for clinicians but only if the information reported is sufficient in quality and content to allow for meaningful adjudication.

In this article, we review case reports of pediatric AEs found in English language medical journals related to children's herb use and assess the quality of the AERs using a scale based on the International Society of Epidemiology's (ISE) “Guidelines for Submitting Adverse Events Reports for Publication.”4 While we do not have enough information to assess causality related to AEs, we can investigate whether case reports document the critical information about the AEs. We hypothesized that there would be a wide variety of adherence to the ISE's guidelines in the documentation of AERs described in case reports and that the overall documentation of the case reports would be poor. While we are not suggesting new guidelines for reporting, we hope to highlight the importance of accurate and complete documentation and reporting of AEs related to herb use.

METHODS

Data Sources

We systematically searched seven databases: Medline, Embase, Toxline, DART, CINAHL, Cochrane CENTRAL, and Global Health from inception through 2010 using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms such as herb, herbal medicine, phytotherapy, medicinal herb, plant extract, natural health products (NHPs), pediatrics, case reports, case series, and safety (see Appendix 1 for all MeSH terms used in the search strategy). Titles and abstracts of identified references were screened by two independent reviewers. Full publications of potentially relevant articles were obtained for further examination.

We checked the references of each included article for additional reports.

Study Selection

We included peer-reviewed case reports/series published through 2010 that described an AE occurring in newborns, infants, children, and youth from birth to age 18. Case reports were of medicinal herbal products taken by any route (eg, oral, topical) by either a child or pregnant woman whose newborn was affected by the product. We did not include non-herb dietary supplements (eg, glucosamine, coenzyme Q10). Dissertations, ab stracts, and non-English publications also were excluded. We also excluded randomized controlled trials as the purpose of this study was to analyze case reports and case series.

Data Extraction

The following data were independently double-extracted into a standardized database: patient demographics, medical history, details of case (eg, how product exposure occurred, medical tests, treatment, and outcome), and product details (eg, name, contents, manufacturer). The main adverse event was characterized according to the primary symptom. If there were differences between reviewer categorization, we resolved it by discussion and consensus.

To assess quality of documentation, we developed a 17-point scale by adapting recommendations from the ISE's “Guidelines for Submitting Adverse Events Reports for Publication.”4 These guidelines were selected because they specifically take into account reporting herbal medicine case reports and the nuances unique to such reports such as the Latin binomial name of the herb and the generic or proprietary name of the herb. Information required for inclusion into our adherence scale was derived from the guidelines.4 One point was allocated for reporting each of the following information: patient age and sex, description of the health condition being treated with the suspected herb, medical history related to the adverse event, physical exam, outcome of the patient (presence or absence of death, life-threatening circumstances, hospitalization or prolonged hospitalization, or significant disability), the Latin binomial name of herb ingredient(s), the generic or proprietary name of herb, the plant part(s) of the herb, the type of preparation (eg, crude herb or extract, pill/capsule, powder), manufacturer, dosage of the herb, duration of therapy, assessment of potential contribution of concomitant therapies, description of AE and its severity compared with established definitions and outcome of AE, and if the report included a discussion. The discussion must address causality, timing, and the presented report's consideration of previously published adverse events. To our knowledge, this scale has not been validated in previous studies.

Based on the ISE's guidelines, our adapted adherence scale represents the most basic level of the information necessary for appropriate case presentation of an AE related to pediatric herb use. Interpretation of the scale was done on each case report.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics using SAS software (version 9.1, SAS Institute Cary, North Carolina). To assess for significant factors associated with studies with higher adherence scores, we used Poisson regression analysis. We categorized variables as follows: age (not documented, 0-23 months, 2-3 years, 4-8 years, 9-13 years, 14-18 years); race (not documented, Non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, African American, Asian, other); gender; time of exposure (postnatal or prenatal exposure); main adverse event reported; route of administration (not specified, intentional oral ingestion, unintentional oral ingestion, intentional topical application, unintentional topical exposure, multiple modes); contaminated or adulterated products; lab analysis of herb; lab analysis of patient; exposure to heavy metals; disposition of patient (not documented, resolution of symptoms following hospitalization, resolution of symptoms with medications or outpatient therapy, death, disability, organ transplantation); location of case; year of publication (before 1980, 1981-1990, 1991-2000, and 2001-2010). Year of publication was further analyzed as cases published before 2007 and after 2007. Journals were categorized as adult or pediatric to assess if journals specializing on children would yield a higher adherence score.

RESULTS

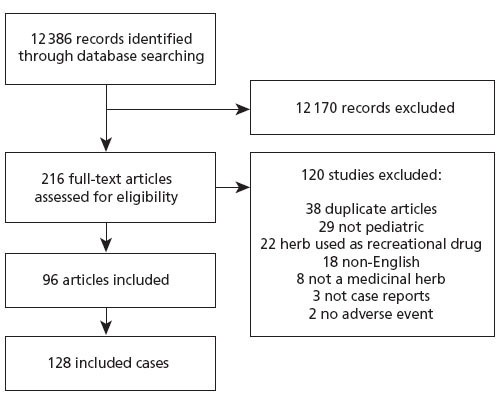

The searches identified 12 386 references. Initial screening of titles and abstracts removed 12 170 references. Full text of the remaining 216 references were obtained and assessed for inclusion. Figure 1 demonstrates our search strategy.

Figure 1 Flow of studies through review.

There were 96 unique articles representing 128 cases included in the analysis (Appendix 2). Table 1 describes the characteristics of the included cases. More than 50% of cases occurred in children 3 years of age or less. In 8% of the cases (n = 10), exposure occurred through maternal transmission to the fetus. Some mothers used herbs for labor and feeding purposes; however, many studies were unclear about duration of herbal use. The most frequent herbs or herbal combinations mentioned in case reports were eucalyptus (n = 12), camphor (n = 10), fennel (n = 6), jin bu huan (n = 6), swanuri marili (n = 6), kharchos suneli (n = 6), tea tree (n = 5), lavender (n = 4), blue cohosh (n = 3), buckthorn (n = 3), liquorice (n = 3), and garlic (n = 3). While many cases reported multiple symptoms, there were a wide variety and severity of symptoms presented (Table 1). The most common (35% of the cases) symptoms were neurological AEs (eg, seizures). Fourteen percent of the cases (n = 18) revealed gastrointestinal disturbances (eg, nausea, vomiting).

Table 1.

General Description of Adverse Events (N = 128 Individual Cases)

| Category | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Not documented | 1 (1) |

| 0-23 mo | 48 (37) |

| 2-3 y | 25 (20) |

| 4-8 y | 23 (18) |

| 9-13 y | 14 (11) |

| 14-18 y | 17 (13) |

| Race | |

| Not documented | 80 (63) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 14 (11) |

| Hispanic | 12 (9) |

| African American | 2 (2) |

| Asian | 8 (6) |

| Other | 12 (9) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 55 (43) |

| Female | 55 (43) |

| Not documented | 18 (14) |

| Time of Exposure | |

| Prenatal | 10 (8) |

| Postnatal | 118 (92) |

| Main Adverse Event Reporteda | |

| Neurological (seizures, central nervous system depression, lethargy) | 45 (35) |

| Gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) | 18 (14) |

| Liver toxicity and jaundice | 14 (11) |

| Cardiovascular/hematological (hypertension, blood toxicity) | 13 (10) |

| Dermatological (rash, burns) | 12 (9) |

| Respiratory (coughing, respiratory depression) | 9 (7) |

| Endocrine/reproductive/renal | 8 (6) |

| Cyanosis | 6 (5) |

| Neonatal withdrawal (drugs or alcohol) | 2 (2) |

| Anaphylactic shock | 1 (1) |

| Route of Administration | |

| Unintentional oral ingestion | 46 (36) |

| Intentional oral ingestion | 37 (29) |

| Topically applied | 22 (17) |

| Multiple modes | 2 (2) |

| Not specified | 2 (2) |

| Unintentional exposure to skin | 1 (1) |

| Contaminated or Adulterated Products | |

| Contaminated products reported in cases | 6 (5) |

| Adulterated products reported in cases | 2 (2) |

| Documentation of testing herb in laboratory | 41 (32) |

| Documentation of laboratory work on patient | 102 (80) |

| Documentation of Exposure to heavy metals | |

| Lead | 9 (7) |

| Arsenic | 2 (2) |

| None | 117 (91) |

| Disposition | |

| Resolution of symptoms following hospitalization | 90 (70) |

| Resolution of symptoms with medications or outpatient therapy | 18 (14) |

| Death | 9 (7) |

| Disability | 7 (6) |

| Organ transplantation | 3 (2) |

| Not documented | 1 (1) |

| Location of case | |

| United States | 40 (31) |

| Europe (continental) | 26 (20) |

| Asia | 21 (17) |

| Australia | 14 (11) |

| Great Britain | 9 (7) |

| Africa | 3 (2) |

| Central America | 3 (2) |

| Unknown | 1(1) |

This reflects the main clinical adverse event in case. Cases may have other symptoms reported.

There was great diversity among route of exposure among the pediatric population discussed. Twenty-nine percent of cases were the result of an intentional ingestion, and 36% were from an unintentional ingestion. In 17% of the cases, the reactive agent was topically applied either as a lotion or bath solution. There were also cases where the child used a product that was contaminated (5%, n = 6) or adulterated (2%, n = 2) associated with an AE. In 7% of the studies (n = 9), the AE was fatal to the individual; however, specific causality was not assessed. Seventy percent reported that the patient had a complete resolution of symptoms following hospitalization. There was a resolution of symptoms with medication or outpatient therapy in 14% of the cases.

Table 2 includes the 17 items based on the AER guidelines and the number of AERs that reflected adherence to this item. Fifty-two percent of studies documented the Latin binomial of the herb ingredients. Documentation of the plant part was evident in 41% of the cases, and 94% documented the type of preparation of the herbal medicine. Thirty-two percent of the cases reported laboratory testing of the herb, and 22% documented the manufacturer of the product. Dosage information revealed that 59% of cases reported the amount of herb taken by the patient. Duration of herb use was documented in 92% of the cases, and 44% of reports included the duration of herb use before the AE. Twenty-two percent included an assessment of the potential concomitant therapies that could have been influential in the AEs.

Table 2.

Adherence Criteria of Adverse Events Case Reports Based on the International Society of Epidemiology's “Guidelines for Submitting Adverse Event Reports for Publication”4

| Item | Description | Point Value | Case With Item Present(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age | 1 | 127 (99) |

| Sex | 1 | 110 (86) | |

| Current health status | Disease or symptoms being treated with suspect herb | 1 | 115 (90) |

| Medical history | Medical history relevant to adverse event | 1 | 101 (79) |

| Physical examination | Abnormal physical or laboratory findings | 1 | 121 (95) |

| Patient disposition | Presence or absence of death, life-threatening circumstances, hospitalization or prolonged hospitalization, or significant disability | 1 | 127 (99) |

| Herb information | Latin binomial name of herb ingredients | 1 | 66 (52) |

| Generic name vs proprietary name of herb | 1 | 113 (88) | |

| Plant part(s) | 1 | 52 (41) | |

| Type of preparation: crude herb or extract | 1 | 120 (94) | |

| Manufacturer: producer of herb | 1 | 26 (20) | |

| Dosage | Dosage: approximate amount of herb | 1 | 76 (59) |

| Duration of therapy: how long herb has been taken | 1 | 118 (92) | |

| Duration of herb use before adverse event | Therapy duration before adverse event and its interface with the adverse event | 1 | 52 (44) |

| Concomitant therapies | Assessment of potential contribution of concomitant therapies | 1 | 28 (22) |

| Description of adverse event | Description of adverse event and its severity compared with established definitions and outcome of adverse event | 1 | 127 (99) |

| Discussion | Presence or absence of evidence supporting causal link including timing, dechallenge, and rechallenge (or state why these were not possible) | 1 | 119 (93) |

| Discussion of previous reports of adverse event in biomedical | |||

| Total points achievable | 17 |

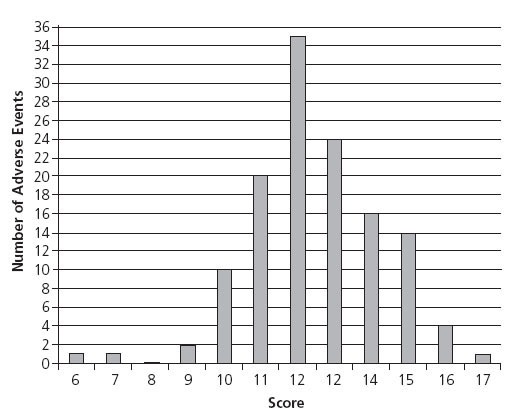

Figure 2 displays the distribution of adherence scores for AEs. Adherence scores ranged from 6 to 17, the highest attainable score. The mean for all scores was 12.5 (SD 1.8) There was no association between a higher score and whether the case report was documented in an adult journal or a pediatric journal (P = .87). There was no correlation between a higher score and the year of publication (P = .51). Table 3 lists several examples of cases that met or almost met all the AER guidelines (15 to 17 points).5–23 This table does not address causality but provides examples of case reports with good documentation.

Figure 2 Number of adverse events by adherence score.

Table 3.

Adverse Event Reports With Adherence Scores of 15 or Greater

| Reference (author, Year) | Adherence Score | Herb common Name (Latin name) | age of child | adverse Event | route of administration or Exposure | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panis et al, 20055 | 17 | Fleeceflower root (Polygonum multiflorum) | 5 y | Acute toxic hepatitis | Intentionally ingested tablets adulterated with anthraquinones | Resolution of symptoms | |

| Humberston et al, 20036 | 16 | Kava kava (Piper methysticum) | 14 y | Acute hepatitis | Intentional ingestion | Liver transplant | |

| Morris et al, 20037 | 16 | Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) | 4 y | Ataxia, unresponsiveness | Unintentional ingestion | Resolution of symptoms | |

| Koren et al, 19908 | 16 | Ginseng (Ginseng siberian) | 1 d | Neonatal hirsutism, androgenous effects | Mother took ginseng while pregnant and breastfeeding for 2 wk | Resolution of symptoms | |

| Jones et al, 19989 | 16 | Blue cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides) | 1 d | Neonatal congestive heart failure | Mother used blue cohosh tablets 1 mo prior to delivery to induce delivery | Hospitalization in neonatal intensive care unit, at 2-y follow-up cardiomegaly present and patient receiving digoxin | |

| Chan et al, 200710 | 15 | Pearl powder (traditional herbal medicine formula) | 9 d | Cyanosis with methemoglobinemia | Intentional ingestion administered for poor feeding | Resolution of symptoms | |

| Henley et al, 200711 | 15 | Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) | 10 y | Gynecomastia | Topically applied to hair with lavender (Lavendula augustifolia) | Resolution of symptoms | |

| Martin et al, 200712 | 15 | Yerba de mate (Ilex paraguariensis) | 1 d | Neonatal withdrawal | Mother drank mate during pregnancy | Reduction of symptoms | |

| Rafaat et al, 200013 | 15 | Garlic (Allium sativum) | 3 mo | Blisters, lesions, and third degree burns | Garlic bulbs applied to feet and ankles | Wounds healed | |

| Garty et al, 199314 | 15 | Garlic (Allium sativum) | 6 mo | Ulceration and lesion | Crushed garlic cloves fixed to wrists | Wounds healed | |

| Darben et al, 199815 | 15 | Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus) | 6 y | Ataxia, weakness, unconsciousness | Topically applied bandages soaked with eucalyptus | Resolution of symptoms | |

| Bagheri et al, 199816 | 15 | Valerian, ballote, hawthorn, passiflora, kola (Valeriana officinalis, Ballota nigra, Crataegus oxyacantha, Passiflora | 13 y | Acute hepatitis | Intentional ingestion of pill for anxiety | Liver transplant | |

| Schmid et al, 200617 | 15 | Broom bush (Retama raetam) | 7 d | Respiratory failure | Intentional ingestion of tea | Hospitalization in pediatric intensive care unit, resolution of symptoms | |

| Bhowmick et al, 200718 | 15 | Goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis) | 11 y | Diabetic ketoacido-sis, hypernatremia, hyperosmolality | Intentional ingestion of tablets for polyuria | Discharged with instructions to discontinue goldenseal | |

| Asiri et al, 200619 | 15 | Myrrh, mahaleb, anise, hauwa (Commiphora molmol, Prunus mahaleb, Pimpinella anisum, Launaea capitata) | 10 mo | Lead toxicity | Herbs pasted to gums for teething | Death of infant | |

| Corazza et al, 200720 | 15 | Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) | 16 y | Acute vulvitis | Oil applied as a kolorex cream with pepper tree (Pseudowintera colorata) | Resolution of symptoms | |

| Florkowski et al, 200221 | 15 | Multi-ingredient with yellow powder and snake extract | 10 y | Adrenal suppression | Intentional ingestion of capsule for asthma and eczema | Resolution of symptoms | |

| Roulet et al, 198822 | 15 | Herbal tea | 5 d | Hepatic vaso-occlusive disease | Herbal tea containing pyrro-lidizine alkaloids consumed through pregnancy | Death of infant | |

| Khandpur et al, 200823 | 15 | Ayurvedic products | 11 y | Hypo- and hyperpig-mented macules all over body, thickening of palms and soles, abdominal pain | Pills and powders intentionally ingested, products contaminated with arsenic | Resolution of symptoms |

DISCUSSION

Upon review of the literature, we found a wide spectrum of AERs with poor documentation related to herb use in children. In our analysis of 128 AERs, the average adherence score for all cases was 12.5 with the highest attainable score being 17. One cannot determine if an herbal product caused an AE if all the information about the patient and the product are not known or reported.

Our results highlight the need for better documentation of AERs in children following herbal product use. In addition to the ISE's guidelines, there are other models of developing standardized reporting in peer-reviewed journals.24,25

The widespread use of herbal products among children necessitates the exploration into the safety of these herbs. While randomized controlled trials are the modern-day gold standard for evaluating efficacy, the sample size is often too small to detect rare but serious harms, and the length of follow-up is often too short to detect harms after prolonged exposure.25 In contrast, case reports can be good sources of information about AEs, especially for new/emerging harms, those that are rare, and those that occur after prolonged use. Case reports, however, cannot determine the incidence of specific AEs. They may only highlight one or several reports of an occurrence. In order to provide an accurate signal of harm, these reports must clarify certain details about the AE.

Like drug AERs, herbal AERs often require additional information, including details of the herbal product (eg, dose/amount taken and duration, exact names of ingredients as listed on the product label), de-challenge/rechallenge information, and patient characteristics. As noted in the reports on products containing ephedra, insufficiently documented case reports hamper informed judgment in evaluating relationships between AERs and a product.26. For example, the person filing the AER should retain a sample of the product, especially if the adverse event is serious, in case testing for adulteration or contamination is indicated. It is especially important for quality documentation of herbal product AERs as there are many types of herbs and preparations available. Improved surveil-lance and comprehensive reporting are necessary for providers and caregivers to make informed decisions about recommending herbal products to children.

In our review, an important finding is the high representation of unintentional ingestions (36%). As with drugs, herbal exposures can be unintentional in nature, either as the result of misuse by a parent or poor supervision of the child. A study by Gryzlak et al examined poison control center reports from 64 centers across the United States and focused specifically on two of the most widely used herbs, echinacea and St John's wort. They found that the majority of exposures for both herbs were in children under the age of 5 years and noted that many exposures were coded as unintentional.27 A high percentage of unintentional ingestions could affect evaluation of toxicity and treatment. For example, these products may be less likely to go through evaluation in clinical trials.

The US Consumer Product Safety Commission requires that oral prescription drugs for children be dispensed in child-resistant packaging unless the drug is exempted or the patient or prescriber requests otherwise. The only dietary supplement with a special packaging requirement is iron-containing drugs and dietary supplements that contain 250 mg or more of elemental iron.28 We also found that some exposures occurred because an herbal product was administered in a manner contradicting its traditional intended use. For example, while the product is beneficial if topically applied, it may cause a negative reaction if ingested (eg, aloe). It also indicates the need for careful labeling of herbal products, clear instructions for use, and monitoring of use.

Our adherence rubric was based on the ISE's “Guidelines for Submitting Adverse Events Reports for Publication.”4 Only one case report contained all the necessary components of a comprehensive AER according to the most basic guidelines. The most commonly missed items were information about the herbal product and the use of any concomitant therapies that could have interacted with the herb. While there were no correlations between adherence score and characteristics of the journal (year of publication or adult vs pediatric journal), there is considerable room for improvement in reporting AEs.

Research suggests that reporting of AEs in case reports has improved over the last decade.29 Ideally, an AER would contain the most accurate and complete information available about the episode. However, one could argue that certain components of the AER may be more important than others. Many of the reports contained a wealth of information but failed to discuss duration of therapy or the presence or absence of concomitant therapies. This could be problematic as there is no way of assessing whether an interaction between therapies could have occurred.

There are many limitations in our study. First, we only assessed published case reports. There is a great need for comprehensive reporting to poison control centers, MedWatch, and other types of journals. The medical literature only has a fraction of all AEs related to herb use. Research has indicated that literature searches for adverse events can be particularly difficult as it requires careful coding and indexing of information.30,31 Thus, there could be missing AERs that we were unable to capture in our searches. We also did not include case reports where herbs were used as recreational drugs, thus underestimating the true number of AEs in the literature. We only included English language case reports and thus did not address whether non-English case reports show similar trends in documentation and types of AEs. We also limited our search to children under 18 years old and therefore did not address AEs from herbal sport supplements that are often used by college-age and older adolescents.

Our adherence scores contained information deemed necessary by ISE guidelines that described herbal products. These guidelines have not been tested extensively, which limits previous research involving these guidelines and thus limits corroboration with our adherence score. There have been other guidelines regarding the reporting of AEs; however, the ISE guidelines include information specific to herbal products.32,33 Lastly, for products unintentionally ingested by the child, it may not be possible for the AER to include information about duration of treatment and symptoms related to the use as it is an unintentional ingestion.

CONCLUSION

Our research suggests that there is need for improvement in reporting of AEs in case reports. While there are no standardized guidelines for all medical journals for case reports, our systematic review provides a starting point for future discussions about appropriate documentation for AERs. The goal is to establish high-quality case reports that provide the most comprehensive information about the products (eg, dietary supplements, medications) and the case history so that causality can be evaluated. Parents and health practitioners need to be aware of the risks and benefits of herbal supplements. Information about risks would be improved with more complete information of AEs in published case reports.

Appendix 1. Search Terms Used for Systematic Review

Search terms used or variations thereof depending on the database searched:

Herbs/natural herbal products

Spermatophyta; herbal drugs; herbal teas; medicinal plants; plant extracts; traditional medicines; medicinal properties; medicinal fungi; ethnobotany; phytotherapy; medicinal plants; herbal medicine; plant extracts; ethnopharmacology; medicinal herb; herbal medicine; plant oils; herbal remedy; medicinal fungi; officinal plants

Pediatric

Children; adolescents; infants; young adults; youth (infant or infancy or newborn or baby or babies or neonate or preterm or premature or postmature), (child or schoolchild or school age or preschool or kid or kids or toddler), (puberty or pubescent or prepubescent); (paediatric or pediatric or peadiatric), (nursery school$ or kindergarten or primary school or secondary school or elementary school or high school$ or highschool), (adolescent or girl or boy or teen); fetus/ or fetal development/ or fetal growth; maternal transmission; prenatal; pregnany; gestation (foetal or fetal)

Case Reports

case reports/ or case studies/ or research/ or trials; case report; case study (case adj3 report), (case adj3 study); spontaneous report (anecdotal adj3 report), (anecdotal adj3 stud$); postmarketing surveillance; post-marketing surveillance

Safety

risk/

safety/ or food safety/

exp poisoning/

(adverse adj3 [event or effect]); side effect; toxicity; (tolerability or tolerance or well tolerated); (adr or adrs or ade or ades); unanticipated event; unanticipated effect; unwanted event; unwanted effect; toxic effect; ([lead or mercury or heavy metal or cadmium or plant or manganese] adj3 poisoning); drug toxicity; (adverse adj3 reaction); herb-drug interactions/

Depending on the database being searched, one or both of the case reports and safety searches were included or sometimes combined.

Appendix 2. References of All Included Case Reports

- Abu Melha A, Ahmed NA, el Hassan AY. Traditional remedies and lead intoxication. Trop Geogr Med. 1987;39(1):100–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asiri Y. Lead toxicity of an infant from home made remedy. Saudi Pharmaceut J. 2006;14:132–5 [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri H, Broue P, Lacroix I, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure after herbal medicine ingestion in children. Therapie. 1998;53(1):82–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick SK, Hundley OT, Rettig KR. Severe hypernatremia and hyperosmolality exacerbated by an herbal preparation in a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2007;46(9):831–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge CK. Hazards of camphorated oil. CMAJ. 1995;153(7):881. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard PR, Burkhardt K, Haenggeli CA, Landis T. Plant-induced seizures: Reappearance of an old problem. J Neurol. 1999;246(8):667–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cade A, Nelson CS. Semecarpus anacardium-induced facial oedema. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135(2):338–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo JV, McNabb J, Perel JM, Mazariegos GV, Hasegawa SL, Reyes J. Kava-induced fulminant hepatic failure. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(6):631–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Anticholinergic poisoning associated with an herbal tea–New York City, 1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44(11):193–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Jin bu huan toxicity in children–Colorado, 1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993;42(33):633–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Lead poisoning associated with use of traditional ethnic remedies–California, 1991-1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993;42(27):521–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challoner KR, McCarron MM. Castor bean intoxication. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(10):1177–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan B, Ui LQ, Ming TP, et al. Methemoglobinemia after ingestion of Chinese herbal medicine in a 9-day-old infant. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007;45(3):281–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury AD, Oda M, Markus AF, Kirita T, Choudhury CR. Herbal medicine induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome: A case report. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2004;14(3):204–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SM, Wilkinson SM. Phototoxic contact dermatitis from 5-methoxypsoralen in aromatherapy oil. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;38(5):289–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corazza M, Lauriola MM, Poli F, Virgili A. Contact vulvitis due to pseudowintera colorata in a topical herbal medicament. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87(2):178–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coruh M, Argun G. Podophyllin poisoning. A case report. Turk J Pediatr. 1965;7(2):100–103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darben T, Cominos B, Lee CT. Topical eucalyptus oil poisoning. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39(4):265–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash HH, Qader A. Tincture opium poisoning in a neonate. Indian Pediatr. 1988;25(9):904–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBellonia RR, Marcus S, Shih R, Kashani J, Rella JG, Ruck B. Curanderismo: Consequences of folk medicine. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(4):228–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Beccaro MA. Melaleuca oil poisoning in a 17-month-old. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1995;37(6):557–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhongade RK, Kavade SG, Damle RS. Neem oil poisoning. Indian Pediatr. 2008;45(1):56–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreisinger N, Zane D, Etwaru K. A poisoning of topical importance. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(12):827–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummer OH, Roberts AN, Bedford PJ, Crump KL, Phelan MH. Three deaths from hemlock poisoning. Med J Aust. 1995;162(11): 592–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando C. Poisoning due to abrus precatorius (jequirity bean). Anaesthesia. 2001;56(12):1178–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel RS, Zarlengo KM. Blue cohosh and perinatal stroke. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(3):302–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florkowski CM, Elder PA, Lewis JG, et al. Two cases of adrenal suppression following a Chinese herbal remedy: A cause for concern? N Z Med J. 2002;115(1153):223–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox DW, Hart MC, Bergeson PS, Jarrett PB, Stillman AE, Huxtable RJ. Pyrrolizidine (senecio) intoxication mimicking reye syndrome. J Pediatr. 1978;93(6):980–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furniss D, Adams T. Herb of grace: An unusual cause of phytophotodermatitis mimicking burn injury. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28(5):767–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garty BZ. Garlic burns. Pediatrics. 1993;91(3):658–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawkrodger DJ, Savin JA. Phytophotodermatitis due to common rue (ruta graveolens). Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9(3):224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gbolade BA. Hypoglycaemic coma in pregnancy and herbal medication. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;13(2). [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DE, Moore GP, Pfaff JA. Camphor ingestion. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7(1):41–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilbert J, Flamant C, Hallalel F, Doummar D, Frata A, Renolleau S. Anti-flatulence treatment and status epilepticus: A case of camphor intoxication. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(12):859–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn TR, Wright IM. The use of black and blue cohosh in labour. N Z Med J. 1996;109(1032):410–1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartnoll G, Moore D, Douek D. Near fatal ingestion of oil of cloves. Arch Dis Child. 1993;69(3):392–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa S, Oda Y, Ichiyama T, Hori Y, Furukawa S. Ginkgo nut intoxication in a 2-year-old male. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;35(4):275–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henley DV, Lipson N, Korach KS, Bloch CA. Prepubertal gynecomastia linked to lavender and tea tree oils. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):479–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hon KL, Leung E, Burd DA, Leung AK. Necrotizing fasciitis and gangrene associated with topical herbs in an infant. Adv Ther. 2007;24(4):921–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz RS, Feldhaus K, Dart RC, Stermitz FR, Beck JJ. The clinical spectrum of jin bu huan toxicity. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(8): 899–903 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CK, Leo P, Shastry D, Meggs W, Weisman R, Hoffman RS. Anticholinergic poisoning associated with herbal tea. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(20):2245–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Higgins EM, Pembroke AC. Oral dexamethasone masquerading as a Chinese herbal remedy. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(2):261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humberston CL, Akhtar J, Krenzelok EP. Acute hepatitis induced by kava kava. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41(2):109–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MR, Hornfeldt CS. Melaleuca oil poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1994;32(4):461–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes SE, Price CS, Thomas D. Essential oil poisoning: N-acetylcysteine for eugenol-induced hepatic failure and analysis of a national database. Eur J Pediatr. 2005;164(8):520–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Jarolim E, Reider N, Fritsch R, Breiteneder H. Fatal outcome of anaphylaxis to camomile-containing enema during labor: A case study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102(6 Pt 1):1041–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha S, Agarwal V. Unusual features in a case of arsenic poisoning. J J Ped Neurol. 2008:69–71 [Google Scholar]

- Jones TK, Lawson BM. Profound neonatal congestive heart failure caused by maternal consumption of blue cohosh herbal medication. J Pediatr. 1998;132(3 Pt 1):550–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajiyama Y, Fujii K, Takeuchi H, Manabe Y. Ginkgo seed poisoning. Pediatrics. 2002;109(2):325–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan B, Schewach-Millet M, Yorav S. Factitial dermatitis induced by application of garlic. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29(1):75–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandpur S, Malhotra AK, Bhatia V, et al. Chronic arsenic toxicity from ayurvedic medicines. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47(6):618–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khine H, Weiss D, Graber N, Hoffman RS, Esteban-Cruciani N, Avner JR. A cluster of children with seizures caused by camphor poisoning. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):1269–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltin D, Uziel Y, Schneidermann D, Kotzki S, Wolach B, Fainmesser P. A case of jatropha multifida poisoning resembling organophosphate intoxication. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2006;44(3):337–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren G, Randor S, Martin S, Danneman D. Maternal ginseng use associated with neonatal androgenization. JAMA. 1990;264(22): 2866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamabadusuriya SP. Neonatal jaundice due to maternal ingestion of "veniwelgata"? Ceylon Med J. 2004;49(1):37–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamens D, De Hert S, Vermeyen K. Tea of thornapple leaves: A rare cause of atropine intoxication. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 1994;45(2):55–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landelle C, Francony G, Sam-Lai NF, et al. Poisoning by lavandin extract in a 18-month-old boy. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46(4):279–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrey D, Vial T, Pauwels A, et al. Hepatitis after germander (teucrium chamaedrys) administration: Another instance of herbal medicine hepatotoxicity. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(2):129–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin I, Lopez-Vilchez MA, Mur A, et al. Neonatal withdrawal syndrome after chronic maternal drinking of mate. Ther Drug Monit. 2007;29(1):127–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNicholl B, Kilroy MK. Transient hypertensive encephalopathy: Possible relation to licorice. J Pediatr. 1969;74(6):963–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metin A, Calka O, Akdeniz N, Behcet L. Phytodermatitis from ceratocephalus falcatus. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;52(6):314–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C, Adler R. Herbal vitamins: Lead toxicity and developmental delay. Pediatrics. 2000;106(3):600–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MC, Donoghue A, Markowitz JA, Osterhoudt KC. Ingestion of tea tree oil (melaleuca oil) by a 4-year-old boy. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(3):169–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyama O, Shigetomi Y, Ohara A, Iitaka K. A boy with recurrent hemorrhagic cystitis during treatment with Chinese herbal medicine. Clin Exper Nephrol. 2002;6(2):121–4 [Google Scholar]

- Murone AJ, Stucki P, Roback MG, Gehri M. Severe methemoglobinemia due to food intoxication in infants. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21(8):536–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy NG, Albin C, Tai W, Benowitz NL. Anabasine toxicity from a topical folk remedy. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2006;45(7):669–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzi G, Dell'omo M, Madeo G, Abbritti G, Caroli S. Arsenic poisoning caused by Indian ethnic remedies. J Pediatr. 2001;139(1): 169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- N Webb A, Hardikar W, Cranswick NE, Somers GR. Probable herbal medication induced fulminant hepatic failure. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41(9-10):530–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Kotajima S. Contact dermatitis from aloe arborescens. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;11(1):51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinuma H, Aoki H, Suzuki T, et al. Two survival cases of severe aconite poisoning by percutaneous cardiopulmonary support system and cardiopulmonary bypass for fatal arrhythmia: A case report. Internet J Emerg Intensive Care Med. 2003;6(2). [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo-Roosens LV, Ontiveros-Nevares PG, Fernandez-Lucio O. Intoxication with buckthorn (karwinskia humboldtiana): Report of three siblings. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007;10(1):66–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panis B, Wong DR, Hooymans PM, De Smet PA, Rosias PP. Recurrent toxic hepatitis in a Caucasian girl related to the use of shou-wupian, a Chinese herbal preparation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41(2):256–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Wiggins J. Eucalyptus oil poisoning. Arch Dis Child. 1980;55(5):405–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch J, Schulz K, Schmidt U, Andresen H, Schwarze B, Dressler J. A comparative study of five fatal cases of taxus poisoning. Int J Legal Med. 2007;121(5):417–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradeepkumar VK, Tan KW, Ivy NG. Is "herbal health tonic" safe in pregnancy; fetal alcohol syndrome revisited. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;36(4):420–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafaat M, Leung AK. Garlic burns. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17(6): 475–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasenack R, Muller C, Kleinschmidt M, Rasenack J, Wiedenfeld H. Veno-occlusive disease in a fetus caused by pyrrolizidine alkaloids of food origin. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2003;18(4):223–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosti L, Nardini A, Bettinelli ME, Rosti D. Toxic effects of a herbal tea mixture in two newborns. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83(6):683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roulet M, Laurini R, Rivier L, Calame A. Hepatic veno-occlusive disease in newborn infant of a woman drinking herbal tea. J Pediatr. 1988;112(3):433–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid T, Turner D, Oberbaum M, Finkelstein Y, Bass R, Kleid D. Respiratory failure in a neonate after folk treatment with broom bush (retama raetam) extract. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(2):124–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewell AC, Mosandl A, Bohles H. False diagnosis of maple syrup urine disease owing to ingestion of herbal tea. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(10):769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkiss M, Holt D. Digitalis poisoning due to the accidental ingestion of foxglove leaves. Ther Drug Monit. 1983;5(2):217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyman T, Stewart MJ, Grove A, Steenkamp V. Adulteration of South African traditional herbal remedies. Ther Drug Monit. 2005;27(1):86–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyman T, Stewart MJ, Steenkamp V. A fatal case of pepper poisoning. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;124(1):43–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom CE. Seizures in a 7-month-old child after exposure to the essential plant oil thuja. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;37(6):446–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp V, Stewart MJ, Zuckerman M. Detection of poisoning by impila (callilepis laureola) in a mother and child. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1999;18(10):594–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman AS, Huxtable R, Consroe P, Kohnen P, Smith S. Hepatic veno-occlusive disease due to pyrrolizidine (senecio) poisoning in arizona. Gastroenterology. 1977;73(2):349–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyan D, Mathew J, Raj M. An unusual manifestation of abrus precatorius poisoning: A report of two cases. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46(2):173–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan JB, Jr, Rumack BH, Thomas H, Jr, Peterson RG, Bryson P. Pennyroyal oil poisoning and hepatotoxicity. JAMA. 1979;242(26):2873–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutrave H, Ravisekar CV, Kumarasamy K, Sathyamurthy B, Venkataraman P, Vasanthamallika TK. Podophyllin poisoning - a case report. Indian J Pract Pediatr. 2003;5(4):360–1 [Google Scholar]

- Theis JG, Koren G. Camphorated oil: Still endangering the lives of Canadian children. CMAJ. 1995;152(11):1821–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uc A, Bishop WP, Sanders KD. Camphor hepatotoxicity. South Med J. 2000;93(6):596–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal C, Quandte S. Identification of a sibutramine-metabolite in patient urine after intake of a “pure herbal” Chinese slimming product. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28(5):690–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb NJA, Pitt WR. Eucalyptus oil poisoning in childhood: 41 cases in South-East Queensland. J Paediatr Child Health. 1993;29(5):368–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf AD, Woolf NT. Childhood lead poisoning in 2 families associated with spices used in food preparation. Pediatrics. 2005;116(2):e314–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo KL TV. Severe hyperbilirubinaemia associated with Chinese herbs. A case report. Singapore Paediatr J. 1996;38(4):180–2 [Google Scholar]

Disclosures The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and none related to this publication was reported. Dr Gardiner is the recipient of Grant Number K07 AT005463-01A1 from the National Center for Complementary & Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NCCAM or the National Institutes of Health. Dr Sunita Vohra receives salary support from Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions as a health scholar.

Contributor Information

Paula Gardiner, Department of Family Medicine, Boston Medical Center, Massachusetts, United States.

Denise Adams, CARE Program, Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

Amanda C. Filippelli, Department of Family Medicine, Boston Medical Center, Massachusetts, United States.

Hafsa Nasser, CARE Program, Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

Robert Saper, Department of Family Medicine, Boston Medical Center, Massachusetts, United States.

Laura White, Department of Biostatistics, Boston University School of Public Health, United States.

Sunita Vohra, CARE Program, Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;(12):1–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Food and Drug Administration Dietary supplement and nonprescription drug consumer protection act. 2006. http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/FederalFoodDrugandCosmetic ActFDCAct/SignificantAmendmentstotheFDCAct/ucm148035.htm Accessed January 30, 2013.

- 3.Dennehy CE, Tsourounis C, Horn AJ. Dietary supplement-related adverse events reported to the California poison control system. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62(14):1476–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly WN, Arellano FM, Barnes J, et al. Guidelines for submitting adverse event reports for publication. Drug Saf. 2007;30(5):367–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panis B, Wong DR, Hooymans PM, De Smet PA, Rosias PP. Recurrent toxic hepatitis in a Caucasian girl related to the use of shou-wu-pian, a Chinese herbal preparation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41(2):256–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humberston CL, Akhtar J, Krenzelok EP. Acute hepatitis induced by kava kava. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41(2):109–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris MC, Donoghue A, Markowitz JA, Osterhoudt KC. Ingestion of tea tree oil (melaleuca oil) by a 4-year-old boy. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(3):169–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koren G, Randor S, Martin S, Danneman D. Maternal ginseng use associated with neonatal androgenization. JAMA. 1990;264(22):2866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones TK, Lawson BM. Profound neonatal congestive heart failure caused by maternal consumption of blue cohosh herbal medication. J Pediatr. 1998;132(3):550–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan B, Ui LQ, Ming TP, et al. Methemoglobinemia after ingestion of Chinese herbal medicine in a 9-day-old infant. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007;45(3):281–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henley DV, Lipson N, Korach KS, Bloch CA. Prepubertal gynecomastia linked to lavender and tea tree oils. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):479–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin I, Lopez-Vilchez MA, Mur A, et al. Neonatal withdrawal syndrome after chronic maternal drinking of mate. Ther Drug Monit. 2007;29(1):127–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rafaat M, Leung AK. Garlic burns. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17(6):475–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garty BZ. Garlic burns. Pediatrics. 1993;91(3):658–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darben T, Cominos B, Lee CT. Topical eucalyptus oil poisoning. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39(4):265–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bagheri H, Broue P, Lacroix I, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure after herbal medicine ingestion in children. Therapie. 1998;53(1):82–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmid T, Turner D, Oberbaum M, Finkelstein Y, Bass R, Kleid D. Respiratory failure in a neonate after folk treatment with broom bush (retama raetam) extract. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(2):124–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhowmick SK, Hundley OT, Rettig KR. Severe hypernatremia and hyperosmolality exacerbated by an herbal preparation in a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2007;46(9):831–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asiri Y. Lead toxicity of an infant from home made herbal remedy. Saudi Pharmaceut J. 2006;14(2):132–5 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corazza M, Lauriola MM, Poli F, Virgili A. Contact vulvitis due to pseudowintera colorata in a topical herbal medicament. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87(2):178–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Florkowski CM, Elder PA, Lewis JG, et al. Two cases of adrenal suppression following a Chinese herbal remedy: A cause for concern? N Z Med J. 2002;115(1153):223–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roulet M, Laurini R, Rivier L, Calame A. Hepatic veno-occlusive disease in newborn infant of a woman drinking herbal tea. J Pediatr. 1988;112(3):433–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khandpur S, Malhotra AK, Bhatia V, et al. Chronic arsenic toxicity from ayurvedic medicines. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47(6):618–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276(8):637–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebrahim S, Clarke M. STROBE: New standards for reporting observational epidemiology, a chance to improve. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(5):946–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haller CA, Benowitz NL. Adverse cardiovascular and central nervous system events associated with dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(25):1833–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gryzlak BM, Wallace RB, Zimmerman MB, Nisly NL. National surveillance of herbal dietary supplement exposures: The poison control center experience. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(9):947–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Consumer Product Safety Commission Requirements under the poison prevention packaging act 16 C.F.R 1700. 2001. http://www.cpsc.gov/en/Regulations-Laws–Standards/Statutes/Poison-Prevention-Packaging-Act/ Accessed January 30, 2013

- 29.Hung SK, Hillier S, Ernst E. Case reports of adverse effects of herbal medicinal products (HMPs): A quality assessment. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(5):335–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golder S, McIntosh HM, Duffy S, Glanville J; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination and UK Cochrane Centre Search Filters Design Group Developing efficient search strategies to identify reports of adverse effects in MEDLINE and EMBASE. Health Info Libr J. 2006;23(1):3–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golder S, Loke YK. The performance of adverse effects search filters in MEDLINE and EMBASE. Health Info Libr J. 2012;29(2):141–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Guideline for industry: Clinical safety data management: definitions and standards for expedited reporting. 1995. http://www.ich.org/products/guidelines/efficacy/efficacy-single/article/clinical-safety-data-management-definitions-and-standards-for-expedited-reporting.html Accessed January 30, 2013.

- 33.Venulet J. Informativity of adverse drug reactions data in medical publications. Drug Inform J. 1985;19(3):357–65 [Google Scholar]