Abstract

As rates of preventable chronic diseases and associated costs continue to rise, there has been increasing focus on strategies to support behavior change in healthcare. Health coaching and motivational interviewing are synergistic but distinct approaches that can be effectively employed to achieve this end. However, there is some confusion in the literature about the relationship between these two approaches. The purpose of this review is to describe a specific style of health coaching—integrative health coaching—and motivational interviewing, including their origins, the processes and strategies employed, and the ways in which they are similar and different. We also provide a case example of how integrative health coaching and motivational interviewing might be employed to demonstrate how these approaches are synergistic but distinct from each other in practice. This information may be useful for both researchers and clinicians interested in investigating or using behavior change interventions to improve health and cost outcomes in chronic disease.

Key Words: Integrative health coaching, motivational interviewing, behavior change, patient education

摘要

随着可预防性慢性疾病的发生 率和相关成本的持续上升,人 们越来越关注支持医疗护理中 行为改变的策略。健康辅导和 激励性面谈是相辅相成但截然 不同的方法,可有效加以利用 以取得最终成果。然而,人们 对这两种方法之间的关系存在 字面上的些许困惑。本综述的 目的是为了描述健康辅导的具 体方式,即综合健康辅导和激 励性面谈,包括两者的起源、 程序和采用的策略,以及两者 相似和不同的方面。我们亦将 提供一个如何应用综合健康辅 导和激励性面谈的病例示例, 展示这两种方法在实践中是如 何相辅相成而又截然不同的。 对调查或使用行为变化干预以 改善慢性疾病健康和成本结果 感兴趣的研究人员和临床医生 而言,此信息将会大有作用。

SINOPSIS

Dado que los índices de las enfermedades crónicas evitables y los costes asociados siguen aumentando, se ha hecho cada vez más hincapié en las estrategias que respaldan un cambio conductual en la asistencia sanitaria. La formación de salud y las entrevistas motivacionales son sinérgicas, pero se pueden emplear de forma eficaz diferentes enfoques para lograr este objetivo. No obstante, hay una cierta confusión en la literatura médica en torno a la relación existente entre estos dos enfoques. La finalidad de esta revisión es describir un estilo de formación de salud específico (formación de salud integradora) y una entrevista motivacional, incluidos los orígenes, los procedimientos y las estrategias utilizados, así como sus similitudes y diferencias. También ofrecemos un ejemplo de caso sobre cómo se pueden emplear la formación de salud integradora y la entrevista motivacional para demostrar de qué manera estos enfoques son sinérgicos pero diferentes entre sí en la práctica. Esta información puede resultar útil para los investigadores y médicos interesados en analizar o usar las intervenciones de cambio conductual para mejorar los resultados sanitarios y económicos en la enfermedad crónica

INTRODUCTION

As rates of lifestyle-related chronic diseases and associated costs continue to rise in the United States, there has been an increasing focus on identifying successful behavioral interventions to help patients prevent and manage disease.1 Two frequently cited behavioral approaches include health coaching (HC) and motivational interviewing (MI). The well-documented methods and effectiveness of MI for improving multiple chronic diseases have been demonstrated over the past 3 decades. Conversely, HC is a relatively new field that has emerged within the last decade and has been conceptualized and operationalized across a continuum of practices with a wide range in quality of care2 and equivocal evidence.3-5 A particular brand of HC—integrative health coaching (IHC)—has been refined and standardized in a similar way to MI, although because of its nascence, the evidence on effectiveness is limited albeit positive.3,6-8

Given the growing interest in behavioral modalities for preventable chronic diseases, the purpose of this article is to review both IHC and MI. We describe their origins, the processes and strategies employed, the ways in which they are similar and different, and a case example where IHC and MI might be applied to demonstrate how these approaches are synergistic but distinct from each other in practice. We have elected to compare IHC (vs HC) because the methods are standardized, have been described in the literature, and thus can be more easily compared to MI. This information may be useful for both researchers and clinicians interested in investigating or using behavior change interventions to improve health and cost outcomes in chronic disease.

INTEGRATIVE HEALTH COACHING

The field of HC is rapidly emerging and with it, a particular brand of coaching called IHC.9 IHC stems from half a century of theoretical literature, 11 years of development at Duke Integrative Medicine (Durham, North Carolina) and the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis), and promising emerging studies. To date, nearly 600 individuals have completed the 113- hour foundational training at Duke, and 50 of these trainees have been certified by Duke after completing 145 hours of additional didactic and practical training as well as one-to-one supervision. At the University of Minnesota, since 2007, approximately 50 individuals have completed a 2-year, 18-credit training either as part of their graduate (master of science, doctoral) program or to earn a graduate certificate in complementary therapies and health practices.10 Although the training processes at each program are different, the approximately 360-hour University of Minnesota training covers similar principles and skills as the Duke training and includes a semester-long internship. Two additional training programs rely heavily on holistic models and also need to be mentioned. These include the Bark Coaching Institute11 and the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS).12 The Bark Coaching Institute has provided a 60-hour training program to 900 participants since 2001 and focuses primarily on training professional nurses in coaching the whole person. The CIIS program offers an integrative wellness coaching certificate embedded within a 2-year, 40-credit master of arts in integrative health that has granted degrees to 37 students since 2010.

Early evidence shows that when offered alone or with patient education, IHC is useful for reducing chronic disease risk and improving health behaviors. A 10-month study of IHC, education, and personalized health planning for cardiovascular disease risk showed a significant reduction in the Framingham Risk Score for those in the intervention group compared to usualcare controls.6 IHC participants also had greater increases in weekly exercise, blood pressure control, and weight loss. Similarly, a randomized control trial of IHC for individuals with type 2 diabetes showed that patients in the IHC intervention reported fewer barriers to medication adherence while reporting improved patient activation, exercise frequency, and perceived health status.3 Furthermore, in the IHC group, there was a significant reduction in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) among patients with elevated HbA1c levels at baseline (17%). A more recent study has shown that IHC as part of a comprehensive model of care reduces stroke and diabetes risk while increasing patient activation, readiness to change health behaviors, and multiple types of exercise.7 In a prospective observational study of health coaching for enrollees in a large, private health plan, Lawson et al found that 89% of participants met at least one self-identified goal and reported improvements in stress levels, healthy diet, physical activity, overall physical and mental health, and patient activation.8

Conceptual Foundations

In general, coaching has been defined as a systematic, collaborative, solution-focused process in which the coach facilitates enhancement of life experience and goal attainment in the personal and/or professional life of clients.13 Individual change occurs as the client actively engages, develops a supportive alliance with the coach, learns to self-assess and explore his or her perception of the issues, and generates possible solutions.14,15 IHC draws from psychology, adult learning theory, and personal development and adapts lessons to healthcare from other areas such as executive coaching.13,16 It is a systematic, collaborative, and solution-focused process that facilitates the enhancement of life experience and goal attainment regarding health. The underlying theoretical model of IHC asserts that behavior changes can be sustained when linked to personal values and sense of purpose.9,14,17-19 IHC helps clients to access the motivation needed to initiate and maintain change by facilitating their ability to consider new perspectives and work with numerous factors that contribute to achieving goals. Such factors include accessing resources and supports, overcoming internal and external barriers to change, and generating alternatives, workarounds, and back-up plans for planned action steps.13,16,20

Process

IHC is an intensive intervention (eg, minimum 6-8 sessions of 30 min–40 min duration) that embodies core aspects of a supportive and creative relationship to elicit change. Well-trained (minimum 100 hours) professional health coaches support the competence of the client by (1) eliciting internal motivation and sense of purpose, connecting health goals to life purpose and personal values9,14,21; (2) building the capacity to change by increasing autonomy, positivity, self-efficacy, resilience, and social and environmental support21; (3) imparting knowledge and education when desired by the client and modeling skills in ways that adults best learn13,22; (4) emphasizing patient accountability, ability to learn, and realistic goal setting through the most challenging stages of change by accessing buried but built-in abilities for learning, mastery, and growth14; and (5) reinforcing the interdependence of positive mental and physical health.21 The client's perceptions of the issue and generation of the solution are explored in the context of the client's values. A wholeperson model and visualization techniques allow IHC to support the clients' own vision of their best selves. Borrowing from other strength-based approaches,21 the coach also trains clients to see the impact of their own positive behavior in bringing about this vision. Finally, the coach plays a key role in helping the client to develop support networks and resources that access the client's community and healthcare system.

IHC follows a process model that moves clients from their vision of their best selves and what is important to them through identification of goals and supporting action steps that reflect their vision and values to the maintenance of achieved goals over time.23 At the first step of visioning, clients may or may not have information from healthcare providers about their current and predicted health status. They conduct a wholeperson self-assessment based upon the Duke Integrative Medicine Wheel of Health,23,24 which depicts the relationship of the client, who rests at the center, to various domains of health, including self-care (nutrition, movement, exercise, and rest; spirituality; mind-body connection; personal and professional development; relationships and communication; and physical environment) and professional care (preventive, interventional, complementary, and alternative), all within the context of mindful awareness. For each of the domains on the wheel, clients reflect on where they are now and where they would like to be. They also are invited to consider how their personal reflection in each domain relates to their vision of optimal health, and they use this vision to identify core values. The client's vision and values then serve as a tether, which the coach uses to help the client identify an area of focus, establish a 3- or 6-month goal in that area, and develop action steps to achieve that goal. Once the goal is achieved and the client determines that he or she can maintain the actions necessary to sustain that goal over time, the client may terminate coaching or move on to another area of focus where the goal-setting, action, and maintenance stages are revisited for a new goal. The process is presented to clients as a somewhat linear process, although in reality, competing commitments present obstacles and goals may be revised as clients progress.

Strategies

IHC uses a number of strategies within a basic structure that enables personalization, optimal patient engagement, empowerment, and successful outcomes. First, specific techniques are employed at different stages of coaching. At the vision and values stages, the coach employs the Wheel of Health assessment and visualization techniques to imagine a healthy best self. Significant attention is given to self-awareness at this stage, where the coach asks the client to hone in on what is most important to him or her. At the focus stage, the coach asks the client to choose an area that he or she is most ready, willing, and able to address that remains consistent with his/her vision and values.7,9 When the client picks a specific goal and designs actions steps to achieve that goal, the coach again asks the client to ensure there is alignment with personal values and sense of purpose.7,9,24 As in many behavior change programs, goals are created to be SMART— that is, specific, measurable, actionable, realistic, and timed.25 The coach works with the client to ensure that every goal and supporting action step meets these criteria so the client knows he or she has identified a goal or action step that is reasonable to achieve in the given timeframe and he or she can evaluate whether it was achieved. Finally, the clients decide when they have achieved maintenance and can continue to sustain their behaviors over time.

Second, the coaching structure and process enable personalization, optimal patient engagement, empowerment, and successful outcomes by training clients to integrate ongoing, nonjudgmental self-assessment and structured ways of thinking about behavior change into their personal learning process, and these are encouraged in multiple ways. First, as noted above, clients learn to compare their current states to their desired states. Second, coaches educate clients on the importance of ongoing self-assessment using a structured way of thinking about behavior change. This structure is presented in a preparation form given to clients to help them prepare themselves for each session. While there is a great deal of variability in how many clients use the form, this tool is valuable to help clients begin to learn the importance of a structured thinking process to change behavior. The preparation forms also mirror the shape of each individual followup coaching session. Both the preparation forms and the follow-up coaching sessions begin with a brief update from the client on action steps and progress toward goals since the previous session. This update is followed by lessons the client has learned while trying new behaviors, including what has worked well, what positive efforts have brought about behavior change, and how the client's sense of self-efficacy has improved.

Next in the structured thinking process, reinforced by both the preparation form and the session's structure, is a discussion of obstacles that have arisen and what strategies were used to try to overcome the obstacles. This part of the coaching discussion further supports the client's ability to problem solve and also normalizes the process of experimentation in learning to generate ultimately successful solutions vs “getting it right the first time.” Importantly, the emphasis here is on the client's efforts and not the outcome. Specifically, coaches reinforce the client's creativity in trying new approaches to solve problems and tolerating perceived failure. The client is then asked where he or she needs support and what kinds of support might be most useful. This may include further brainstorming on how the client wants to move forward, exploration of mindset with further perspective-taking, generation of possible additional strategies to overcome remaining obstacles, and/or further affirmation of competencies. The coaching preparation form and session end with the client defining and committing to a specific action that moves the client closer to his or her self-defined goal.

Scaling questions are a third mechanism used to train clients in self-assessment and structured thought throughout the coaching process. Similar to MI,26 scaling questions are frequently used by coaches to ask clients to assess their self-selected goals and supporting action steps by rating their level of importance, confidence, or other relevant variable. For example, the coach might ask a client to rate his or her level of confidence on a 10-point scale of being able to complete the 30-minute, four-days-per-week walking program the client had set as a goal. If the client said 5, the coach would ask the client, “Why not a 2?” By asking the client why not a lower number (vs a higher number), the client verbalizes those reasons in favor of the behavior goal. This may result in increasing confidence, maintaining the goal as is, and developing strategies for success (eg, schedule walking time on the calendar, commit to walking with a friend two of the days). Conversely, despite focusing on reasons to change, the client may recognize the need to revise the goal to be more manageable (eg, reduce the amount of time each day or the number of days per week). Similarly, the coach might ask the client how valuable a particular outcome or action is to them, again on a 10-point scale. If the client names a low number, the coach might ask what outcome would be more valuable.

The specific structure and techniques described above are used with multiple interpersonal processes throughout the coaching. These interpersonal processes include the following: active listening and use of reflections, motivational language,27 open-ended powerful questions, and consistently broadening perspectives. The first three are the same processes used in MI and humanistic psychotherapeutic approaches.26,28,29 Active listening and reflections serve to increase the client's self-awareness while demonstrating the coach's empathy and acceptance. Reflections can be simple, complex, double-sided, or summary. When done skillfully, both techniques give clients their words back while highlighting movement toward change. Similarly, the use of motivational language catalyzes change through subtle shifts in clients' perception. Open-ended powerful questions are designed to further increase the client's self-awareness, capacity for thinking about new ways of being, and potential for change. This approach helps the client to consider his or her situation from multiple points of view, so that new understandings and possibilities for action may arise.30 Perspectives work often includes the use of metaphors to invite creative problem solving.31 Qualitative, empirical work demonstrates that the structure of the session (described above), as well as these specific interpersonal processes, synergize to create a sense of autonomy and empowerment in the client.27

MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING

MI was first introduced in the literature 30 years ago.32 Since that time, nearly 1500 studies of its effectiveness have been published, and its developers, William Miller and Stephen Rollnick, estimate at least 15 million individuals have been intended recipients of MI through their Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers. Originally developed for individuals with alcohol use disorders,32 the use of MI has expanded to support behavior change in a number of chronic diseases, including other substance use disorders, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, chronic pain, and asthma.33-36

Conceptual Foundations

MI was initially defined as “a client-centered, directive method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence.”26(p25) More recently, MI was specified as “a clinical or communication method.”26(p131) Its conceptual origins were a combination of three psychological theories.33,37,38 Cognitive dissonance (Leon Festinger) and self-perception (Daryl Bem) both support the idea that hearing oneself argue for change actually promotes one's capacity for change. Carl Rogers' person-centered theory identified necessary and sufficient conditions for change (eg, therapist's empathetic understanding, unconditional positive regard, and congruence) that are central to the MI clinical style.39 Although some scholars have identified the Transtheoretical Model of Change (TTC) as a theoretical foundation for MI, Miller and Rollnick explicitly deny that claim, instead defining the relationship between the two as “kissing cousins.”37(p130) They further separate MI from the TTC by stating that the TTC can be helpful in conceptualizing where individuals are in terms of their readiness for change and how they might progress from readiness to action through the use of MI. However, they specifically note that the TTC is not necessary to understand or implement MI.37

Process

Miller and Rollnick have clearly stated that MI is a brief method of communication (1-2 sessions) designed to move individuals in the direction of change.26,33,37 To that end, MI consists of two main phases: phase 1, increasing motivation for change, and phase 2, consolidating the commitment to change.33 Before describing the two phases, however, it is important to review several key elements that constitute MI. First, there is what has been called the “spirit” of MI, or the clinical way of being.26 The qualities embodied in this spirit include establishing collaboration with clients as opposed to establishing an expert role, focusing on eliciting clients' own motivations for change vs educating them about why they should change, and honoring clients' autonomy to decide to change—or not—as opposed to assuming the authority to tell them how to change. This spirit reflects the client-centered nature of the process, with the caveat that MI diverges from pure client-centeredness because it is a directive method that is consciously goal-oriented toward making a change in some behavior that is noted to be unhealthy (eg, substance use).33,38

Also central to MI are what Miller and Rollnick term the “four guiding principles,” which begin to move from the spirit of MI to the actual practice.26 These principles include expressing empathy, developing discrepancy, rolling with resistance, and supporting self-efficacy. Expressing empathy includes acceptance of what is, understanding that ambivalence is normal, and using the skill of reflective listening so clients hear their own words, as opposed to those of the provider.26 The provider then helps the client to develop discrepancy between current behaviors or the status quo and what the client would like things to look like in the future.26 Importantly, the discrepancy needs to be based on what is important to the client and not to the provider so that the client begins to hear his or her own reasons for changing. Rolling with resistance is a strategy that honors where the client is in terms of thinking, feeling, and acting. Rather than push for change, the provider understands that the solutions reside within the client.26 Finally, the provider supports self-efficacy by understanding that clients' beliefs about their ability to change are directly related to their capacity to change. Thus, core to the provider-client relationship is the provider's strong belief in the client's ability to decide when and how to make desired changes.26,32

Strategies

With the spirit of MI as a backdrop, the provider engages in phase 1 by helping the client to resolve ambivalence and increase motivation for change.26 There are five key skills or strategies that are used in this stage. Four of these skills are identified by the acronym OARS, which stands for open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries.26,37 Open-ended questions invite deeper consideration and create momentum toward change by helping clients to explore their own reasons for making a change. Affirmations acknowledge clients' strengths and support self-efficacy. Reflections, or reflective listening, are where the provider skillfully feeds back to the client what he or she has said, thereby demonstrating empathy and inviting the client to focus on the positive aspects of change that the client has selfidentified. Summaries are a specific type of reflection where the provider emphasizes what has been said and if appropriate, highlights both sides of ambivalence to help develop discrepancy.

The fifth skill, identifying and reinforcing change talk, includes those things the client has said that reveal an interest in, motivation for, or commitment to change.26,37 There are five main categories of change talk: desire for change, ability to change, reasons to change, the need for change, and the commitment to change.37,38 By focusing on change talk, the provider reinforces the client's own reasons for wanting to change, thereby reducing resistance.39 Once the client is engaged in change talk, the provider can use a number of strategies to elicit and strengthen change talk, including asking evocative open-ended questions; using importance and confidence rulers (eg, On a scale of 1 to 10, how important is it for you to make this change?); exploring the pros and cons of current behavior; asking the client to elaborate on a statement made in the direction of change; asking about the extremes of changing or not (eg, What is the best/worst that might happen?); looking forward (eg, What might it be like if you stayed the same and if you changed?) or backward (eg, What did past success look like?); and exploring goals and values to identify what is important to the client.39 These skills are revisited to increase change talk and subsequently increase the motivation for making a change.

Phase 2 involves strengthening the commitment to change and making a plan to act.26 The provider assesses whether the client is indeed ready to make the shift from enhancing motivation to committing to change. He or she then continues to build on the client's sense of responsibility and personal choice to begin discussing strategies for change.26,39 The first step in this phase involves a previously discussed strategy of summarizing. Specifically, the provider summarizes the content of phase 1, including the client's perceptions and ambivalence related to the problem, the client's change talk, relevant objective evidence the provider has that is important to the change, and the provider's assessment of the situation with a focus on where it overlaps with the client's concerns.26 The provider continues to rely on the client as the expert by asking how he or she wants to approach making the change. This is a time when the provider may offer advice if (1) the client requests it or (2) the client gives the provider permission to do so.26

Through discussion of potential options for change, a change plan will be developed that includes goal setting, consideration of options for change, establishing a plan, and obtaining verbal commitment to the plan.26 In each of these steps, the client retains autonomy over which goals to set and how to achieve them. The provider's role is to continue to ask openended questions that support the commitment to change while also helping the client to establish his or her own specific steps for achieving that change.26,39 Once the client develops a plan, the provider will obtain the client's verbal commitment to follow the plan and reinforce this decision by summarizing what the client says he or she wants to do and how it will be accomplished.39 Once the client makes a verbal commitment to the change plan, MI concludes, although it may be interwoven with other forms of treatment moving forward.39

SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES BETWEEN INTEGRATIVE HEALTH COACHING AND MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING

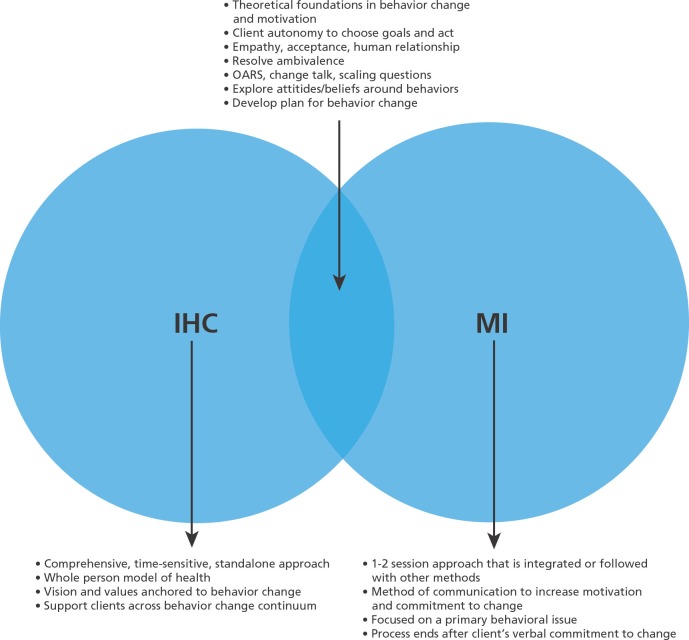

While IHC and MI are both approaches to address behavior change and in some studies MI has been termed HC,40-42 they are overlapping but distinct approaches. The Figure represents these two approaches as a Venn diagram. Similarities include the following. Both approaches have conceptual foundations in theories of behavior change and intrinsic motivation. In both approaches, clients have the autonomy to determine the specific goals they will set and how they will achieve them. Both approaches place heavy emphasis on the provider- client relationship and the importance of empathy, acceptance, and human relationship. Attention to resolving feelings of ambivalence is important in both and with this, the need to explore attitudes and beliefs around behaviors. Finally, both approaches include working with the client to develop a plan for behavior change.

Figure.

Integrative health coaching and motivational interviewing: Venn diagram of synergistic and distinct elements.

Abbreviations: IHC, integrative health coaching; MI, motivational interviewing; OARS, open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries.

Differences between IHC and MI include the following. IHC is a comprehensive intervention with a minimum of six sessions, while MI is designed to be brief, lasting only one or two sessions. Additionally, IHC is a standalone approach, whereas MI is used simply to increase motivation and commitment to change; once that is achieved, other approaches ensue. IHC uses a model of whole-person health when considering change, whereas MI is focused on the primary behavioral issue. IHC helps clients to develop a vision and identify core values to sustain change over time, whereas MI brings in the issue of values only to develop discrepancy and move clients toward a commitment to change. IHC also sees clients through the whole process of change, whereas MI ceases once a plan for change has been developed. Given these similarities and differences, it may be helpful to conceptualize IHC as incorporating MI and moving beyond it. A case example presents this possibility.

CASE EXAMPLE

The following is a case example of how IHC and MI would look different for the same patient. A 67-year-old woman presents for a primary care visit with her daughter, who is her primary caretaker. The patient is obese, has hypertension and type 2 diabetes, and is taking insulin. She has limited mobility and remains primarily homebound. Her most recent HbA1C was 11.3%, up from 9.6% 3 months earlier. Through the course of the visit, the provider learns from the patient's daughter that she consumes fullsugar soda daily, brought by the patient's friends. Medication reconciliation demonstrated that the patient is not adhering to daily medications. The provider's primary concern is the patient's uncontrolled diabetes and associated behaviors, including poor medication adherence and a high sugar intake.

Integrative Health Coaching

If this patient were referred to IHC, the coach would begin by asking the patient to complete the current and desired states form to self-assess where she is and where she would like to be on each of the domains of the Wheel of Health. The coach then would lead the patient through a envisioning exercise so she could articulate her desired future vision of health and wellbeing (session 1). From this exercise, the coach would use open-ended questions to ask the patient to articulate what are important values associated with this vision. This process of self-discovery would help the patient to become clear about what is most important to her and where she ideally wants to be (session 2). The vision and values would become an anchor for future coaching conversations. The coach would ask the client what she understands about her most recent visit with the physician and how her current health might be getting in the way of achieving her vision or might be conflicting with her values. This conversation would lead to the coach asking the patient where she would like to focus. This focus area might be specific to diabetes care (eg, improve medication adherence) and might not (eg, improve social relationships) (sessions 3-4). The coach would then help the patient to identify a 3- to 6-month goal that is SMART. Once the SMART goal is identified, the coach would ask the patient where she would like to begin—Which action could she take in the next week to move toward this goal? The coach would help the client to SMART the action step (session 5). The coach would continue to work with the client on action steps to achieve the goal (sessions 6-8). Once the goal is achieved and the client feels comfortable she can maintain it, the client would terminate coaching or select another area of focus (session 9 and if a new goal, beyond). If the patient were terminating coaching, the coach would reinforce the work the patient has done to date and ensure that support systems are in place to sustain her changes over time. For each session, the coach would ask the client to complete a coaching preparation form so that she can articulate where she has been, what she learned, where she would like to go moving forward over the next week or two, and what she will need to do to make that happen, including accessing resources and support. The final coaching preparation form would ask the client to highlight key learning about herself and how she will use this knowledge moving forward to maintain all she has accomplished.

Motivational Interviewing

For this patient, MI sessions would occur once or twice to help her achieve better diabetes control. The focus of these sessions would be to increase the patient's motivation for and commitment to improving diabetes control. The mechanisms to achieve better diabetes control would be up to the patient. The provider would focus first on helping the patient to resolve any ambivalence over making changes to improve diabetes control, using OARS and identifying and eliciting change talk, while rolling with any resistance that may arise. Once the provider determines that the patient's motivation to change is high, the discussion would turn to developing a plan for change. The patient would establish her own goal for change and a plan to achieve it. Once a plan was outlined, the provider would summarize the plan created and solicit a verbal commitment from the patient to that plan. The MI sessions would terminate; however, the patient may be referred for additional support services, especially depending on the specific components of the plan.

This case example demonstrates how IHC and MI would look for the same patient. IHC actually uses many of the MI processes, in addition to other interpersonal techniques, to help empower the client and support the client's ability to change. However, while both approaches use reflection, open-ended questions, and motivational language to support the patient to change behavior, the IHC approach is much more comprehensive and sees the patient through the entire change process. Conversely, while MI still works with the patient to establish a plan for behavior change, once that plan is articulated, MI ceases. Additionally, the focus on whole person health in IHC means that patients may establish a goal that is not directly related to a chronic condition, although achieving this goal may be necessary before other goals may be addressed.

SUMMARY

IHC and MI are both useful approaches for helping patients to achieve behavior change in healthcare settings. IHC is a more comprehensive approach that considers patients holistically and supports them across the entire behavior change journey. Conversely, MI is a communication method and interpersonal style that focuses specifically on helping patients to resolve ambivalence and make a commitment to change. Both approaches have origins in behavior change theories and use interpersonal skills that emphasize empathy and meeting patients where they are. With its focus on self-assessment, continued learning, and personal development, IHC has the capacity to teach patients lifelong skills that may be harnessed when addressing future health or other behavior changes. However, it is a time-intensive process that requires significant personal investment to be most successful. MI is a useful communication method for healthcare providers to incorporate into routine clinical care because there is a limited amount of time to help move patients toward behavior change. Since it is not a stand-alone method, additional resources are generally necessary to help patients enact the change plans they commit to, such as support from a behavioral therapist. Finally, MI is a method that coaches can use successfully with patients as part of the comprehensive IHC approach. With the ongoing challenge of reducing rates of preventable chronic disease through behavior change, both IHC and MI are valuable approaches to achieve this end.

Disclosures The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and Drs Simmons and Wolever disclosed receipt of a grant from the Duke Center for Personalized Medicine and National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr Simmons also disclosed that she provides integrative health coaching to private clients.

Contributor Information

Leigh Ann Simmons, Duke University School of Nursing, United States..

Ruth Q. Wolever, Duke Integrative Medicine, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Durham, North Carolina, United States..

REFERENCES

- 1.Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolever RQ, Eisenberg DM. What is health coaching anyway? Standards needed to enable rigorous research: Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(22):2017–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolever RQ, Dreusicke M, Fikkan J, et al. Integrative health coaching for patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(4):629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289(16):2083–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frosch DL, Uy V, Ochoa S, Mangione CM. Evaluation of a behavior support intervention for patients with poorly controlled diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(22):2011–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edelman D, Oddone EZ, Liebowitz RS, et al. A multidimensional integrative medicine intervention to improve cardiovascular risk. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):728–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolever RQ, Webber DM, Meunier JP, Greeson JM, Lausier ER, Gaudet TW. Modifiable disease risk, readiness to change, and psychosocial functioning improve with integrative medicine immersion model. Altern Ther Health Med. 2011;17(4):38–47 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawson K, Jonk Y, O'Connor H, Riise K, Eisenberg D, Kreitzer M. The impact of telephone health coaching on health outcomes in a high-risk population. Global Adv Health Med. 2013;2(3):40–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolever RQ, Caldwell KL, Wakefield JP, et al. Integrative health coaching: an organizational case study. Explore (NY). 2011;7(1):30–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreitzer MJ, Sierpina VS, Lawson K. Health coaching: Innovative education and clinical programs emerging. Explore (NY). 2008;4(2):154–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bark L. The wisdom of the whole: coaching for joy, health, and success. San Francisco, CA: Create Space Press; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 12.California Institute of Integral Studies Career preparation in integrative health studies. www.ciis.edu/Academics/Graduate_Programs/Integrative_Health_Studies/Career_Preparation.html Accessed June 10, 2013

- 13.Stober DR, Grant AM, editors. Evidence based coaching handbook: putting best practices to work for your clients. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant AM. An integrative goal-focused approach to executive coaching. In: Evidence based coaching handbook: putting best practices to work for your clients. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2006:17–50 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant AM. The impact of life coaching on goal attainment, metacognition and mental health. Soc Behav Pers: Int J. 2003;31(3):253–63 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hudson FM. The handbook of coaching. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deci EL, Ryan RM. Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. J Happiness Stud. 2008;9(1):1–11 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheldon KM, Elliot AJ. Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal wellbeing: the self-concordance model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76(3):482–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheldon KM. The self-concordance model of healthy goal striving: when personal goals correctly represent the person. In: Deci EL, Ryan RM, editors. Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2002:65–86 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams P, Davis DC. Therapist as life coach: transforming your practice. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kauffman C, Moore M. Positive psychology: the science at the heart of coaching. http://www.instituteofcoaching.org/images/pdfs/PosPsychHeartof-Coaching.pdf Accessed June 10, 2013

- 22.Berger JG. Adult development theory and executive coaching practice. In: Stober DR, Grant AM, editors. Evidence based coaching handbook: putting best practices to work for your clients. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006:77 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith LL, Lake NH, Simmons LA, Perlman AI, Wroth S, Wolever RQ. Integrative health coach training: A model for shifting the paradigm toward patient-centricity and meeting new national prevention goals. Global Adv Health Medicine. 2013;2(3):66–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liebowitz R, Smith L, Gaudet TW, Duke Center for Integrative Medicine The Duke encyclopedia of new medicine: conventional and alternative medicine for all ages. London; New York, NY: Rodale; 2006:640 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strecher VJ, Seijts GH, Kok GJ, et al. Goal setting as a strategy for health behavior change. Health Educ Q. 1995;22(2):190–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. London: Guilford; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caldwell KL, Gray J, Wolever RQ. The process of patient empowerment in integrative health coaching: how does it happen? Global Adv Health Med. 2013;2(3):48–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogers CR. Client-centered therapy: its current practice, implications and theory. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1951 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burleson BR, MacGeorge EL, Knapp M, Daly J. Supportive communication. In Knapp ML, Daly JA, editors. Handbook of interpersonal communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2002;3:374–424 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hubble MA, Duncan BL, Miller SD. The heart and soul of change: what works in therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yapko MD. Trancework: an introduction to the practice of clinical hypnosis. New York, NY: Routledge; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller WR. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behav Psychother. 1983;11(2):147–72 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lundahl B, Burke BL. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: a practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(11):1232–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armstrong M, Mottershead T, Ronksley P, Sigal R, Campbell T, Hemmelgarn B. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12(9):709–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(5):843–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2009;37(2):129–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64(6):527–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller WR, Moyers TB. Eight stages in learning motivational interviewing. J Teaching Addict. 2006;5(1):3–17 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogedegbe G, Fernandez S, Fournier L, et al. The Counseling Older Adults to Control Hypertension (COACH) trial: design and methodology of a groupbased lifestyle intervention for hypertensive minority older adults. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35(1):70–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sahlen K, Johansson H, Nyström L, Lindholm L. Health coaching to promote healthier lifestyle among older people at moderate risk for cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and depression. a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial in Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2013March6;13:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Browning C, Chapman A, Cowlishaw S, et al. The Happy Life Club™ study protocol: A cluster randomised controlled trial of a type 2 diabetes health coach intervention. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]