Abstract

Women's health encompasses a continuum of biological, psychological, and social challenges that differ considerably from those of men. Despite the remarkable advances in science, women's health and sex differences research is slowly gaining recognition and acceptance. It is important that women's health gain attention as women are usually the gatekeepers of care for the family. Women's health and health outcomes are strongly influenced by sex and gender differences as well as geography. Around the world, the interplay of biology and culture brings about differences in men's and women's health, which have been largely overlooked. The Women's Health: Increasing the Awareness of Science and Knowledge (WHISK) Pilot Project was a multidisciplinary project aimed to increase the awareness of sex and gender differences in women's health and research among healthcare professionals. Theater expression and creative art were used to translate knowledge, enhance understanding, and increase the awareness of sex differences. Findings from this project clearly showed an apparent increase in knowledge and cultivation of new insights.

Key Words: Sex and gender differences, women's health, community engagement

抽象

女性健康围绕着一个由生物、心理和社会挑战组成的连续统一体,而该等挑战与男性所面临的挑战有很大区别。尽管我们在科学上已经取得了非凡的进展,但女性健康和两性差异研究却还在逐步获得认可和接受。关注女性健康至关重要,因为女性通常担负着守护家人健康的重任。女性健康和健康结果受两性和性别差异以及地域的强烈影响。

在全世界范围内,生物学与文化之间的相互作用造成了男性健康与女性健康的差异,而这却在很大程度上被人们所忽视。WHISK 试点项目是一个多学科项目,旨在提高医疗护理专业人士对女性健康和研究方面的两性和性别差异的意识,并采用戏剧性的表达和创造性的艺术来解释

两性差异知识,增强对两性差异的理解和提高对两性差异的意识。本项目的发现清楚表明,医疗护理专业人员对相关知识的知晓程度明显提高,并且还培养出许多新的观点。

SINOPSIS

La salud de las mujeres abarca un continuo de retos biológicos, psicológicos y sociales que difieren considerablemente de los de los hombres. Pese a los notables avances de la ciencia, la investigación sobre la salud de las mujeres y las diferencias entre sexos va obteniendo reconocimiento y aceptación con mucha lentitud. Es importante que la salud de las mujeres consiga atraer la atención, pues las mujeres controlan por lo general el acceso de la atención médica a la familia. La salud y los resultados médicos de las mujeres están fuertemente influidos por las diferencias de sexo y género y por la geografía. En todo el mundo la interacción entre biología y cultura provoca diferencias entre hombres y mujeres en cuanto a la salud, diferencias que durante mucho tiempo se han obviado. El proyecto piloto WHISK fue un proyecto multidisciplinario cuyo objetivo era aumentar la concienciación sobre las diferencias de sexo y género en la salud de las mujeres y la investigación entre los profesionales sanitarios. Se utilizó la expresión teatral y el arte creativo para reflejar los conocimientos, ampliar la comprensión y aumentar la concienciación sobre las diferencias entre sexos. Los resultados de este proyecto mostraban con claridad un visible aumento del conocimiento y el desarrollo de nuevas perspectivas.

INTRODUCTION

Women's health encompasses a continuum of biological, psychological, and social challenges that differ considerably from those of men.1 Despite the remarkable advances in science, women's health and sex differences research is slowly gaining recognition and acceptance.2 It is important that women's health gain attention as women are usually the gatekeepers of care for the family. Women's health and health outcomes are strongly influenced by sex and gender differences as well as geography. Around the world, the interplay of biology and culture brings about differences in men's and women's health, which have been largely overlooked.3 When it comes to health among the sexes (men and women)—sex does matter. Although women tend to live longer than men (on average 5 years) almost everywhere, they suffer from more illnesses and disabilities throughout their lives.1

SEX AND GENDER DIFFERENCES IN WOMEN'S HEALTH

Though women's health often is the focus of diseases such as breast and ovarian cancers and those of the reproductive system, it is in fact a much more encompassing field, and the study of health and disease in both sexes is important to advancing the health of women.4 According to Clayton and Joseph (2013), the goal of sex differences research is to learn how biologic mechanisms, disease manifestation, and therapeutic responses may be developed. Furthermore, sex differences research has the power and robustness to be beneficial to both men and women by informing the delivery of more personalized, sex-appropriate care3 and gender-specific medicine. It is critical that new advances in research and science and the translation of new information be shared across the spectrum of healthcare professionals to advance women's health.

The initial focus of “sex and gender” health emerged at the level of medical education.5 However, initiatives to integrate gender issues or women's health issues into the curricula have gained momentum. As efforts continue to address this critical need, researchers, educators, and healthcare providers struggle with how to incorporate information generated from the growing discipline of sex and gender–based medicine into educational and training programs that will ultimately impact patient care5 and improve health outcomes for women.

The Association of Schools of Public Health (ASPH) in collaboration with the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) conducted a study to assess how women's health is addressed in required public health education.6 The primary findings of the project suggested that public health curricula should incorporate various educational components of sex differences (eg, knowledge of the major sex differences in health across the life span). Specific findings suggested that sex and gender differences, diversity within gender, social determinants of health, and a lifespan perspective should provide the foundational efforts to incorporate women's health into public health core curriculum.7 Through this project, ASPH and its federal partners sought to increase available information regarding women's health issues across the life span.

ART AND HEALTH

During the past decade, health professionals have cautiously begun to look at the variety of ways in which art might be used to heal emotional injuries, increase understanding of oneself and others, develop a capacity for self-refection, reduce symptoms, and alter behaviors and thinking patterns.8 The use of art-based health research (ABHR), arts, and new media can serve as vehicles for change and knowledge dissemination. ABHR, an interdisciplinary collaboration among arts, humanities, health, and social sciences, is receiving much attention, characterized by enthusiasm for the creation of new knowledge and new forms of knowledge translation.9 As a matter of fact, there is a burgeoning of ABHR in various fields including education, nursing, sociology and other sciences, and communication studies.10

Theatrical expression is an ancient tradition and has taken on countless forms and purposes throughout history.11 Furthermore, since its inception as an art form, theater, or dramatic representation, has been used not only for the purposes of entertainment but also as means to inspire thought, critical reflection, emotional engagement, and personal transformation.10 According to Rossiter et al (2008), theater has a rich history of imparting information. However, researchers have been slow to bridge this disciplinary chasm, and this is especially true for medical and health-related knowledge.

One of the ways that people come together to be heard and influence their communities is through community-based theater.12 Community-based theater is a form of sociopolitical theater that takes a critical position toward social issues like women's health and aims to raise the awareness. Moreover, community-based theater is a form of grassroots theater embedding art and scholarly outreach that includes significance (importance of the issue); context (appropriateness of the expertise and methods); scholarship (addresses application, generation, and utilization of the knowledge); and impact (consists of the effect and benefits of the project issues).13 A powerful component of community-based theater is the sharing of commonality. Theater groups focus on examining social issues through their works and often share common experiences in their day-to-day lives.13 In addition, theatrical activities often relate to personal and social change processes.

METHODS

The Women's Health: Increasing the Awareness of Science and Knowledge (WHISK) Pilot Project was a multidisciplinary project that aimed to increase the awareness of sex and gender differences in women's health and research among university/college students, faculty, librarians, and health professionals. An objective of the project was to increase healthcare professionals′ awareness of, access to, and utilization of, the National Library of Medicine's women's health electronic resources. In addition, the researchers incorporated sex and gender based differences research and health outcomes into existing curricula in relevant courses (eg, the public health program, nutritional sciences and nursing programs, and health education and women's studies departments). As the primary goal of this project was to increase awareness of sex and gender differences in women's health and research, the social marketing model was selected to guide its implementation. The social marketing model includes six phases: planning and strategy, selecting channels and materials, developing pre- and posttesting, implementation, assessing effectiveness, and considering feedback for refinement.6 In addition, we employed creative arts and community-based theater to engage our audiences and social networking and technology as vehicles for recruitment.

We focused on creative arts communication and community-based theater to transfer knowledge and to increase the awareness of women's health and wellness research. Our aim was to focus on how art-based approaches can contribute to knowledge awareness and translation, women's health, and well-being.

The project was conducted on the campus of Morgan State University (MSU), a 4-year coeducational institution located in a residential section of Baltimore, Maryland, in the United States. Nestled within the urban academy, there is total of 7226 students and more than 630 faculty members. MSU is the home of the School of Community Health & Policy (SCHP), which is the primary site for the project due to its expertise in public and community health, health equity, the social determinants of health, and social justice.

Participants were recruited via traditional formats such as flyers and postcards. However, we also employed social networking and technology (eg, Facebook, Twitter) to recruit a new generation of scholars. According to the Pew Research Center, minority adults outpace whites in their use of social technologies.14 The inclusion criteria were healthcare professionals, particularly females, whom were recruited from the public health, nursing, nutritional sciences, and health education programs between July 13, 2012, and September 12, 2012. However, we opened up our training sessions to others who were interested in women's health/wellness and sex differences.

From July 13, 2012, through September 12, 2012, we provided sex differences educational training and out-reach to a total of 309 participants, who included health-care professional faculty (50 participants), students (126 participants), and special groups (43 participants of female-led peer educators and sororities) through creative arts and community-based theater.

SCHP collaborated with a community grassroots organization, Womb Work Productions Inc (Baltimore, Maryland). Womb Work is a fully comprehensive production company that uses performing arts as a tool to provide education and increase the awareness of pertinent issues (eg, women's health, HIV/AIDS, world hunger). This provided an opportunity for the application of new learning.

The most widely used evaluation design is a traditional pre- and posttest, where participants are asked a series of questions at both the beginning of a program (pretest) and then again at the program's completion (posttest). This design is believed to measure changes in participants′ knowledge, attitudes, or behaviors regarding the program content (eg, sex and gender differences). The idea of pre- and posttests is often accepted as a viable method to assess the extent to which an educational program has had an impact on learning. To assess knowledge of sex differences in women's health/health outcomes and research, a pretest/posttest design was implemented to assess any new learning among the participants. The primary questions, listed below, were constructed based on measurements of awareness and knowledge of sex and gender differences in women's health, health outcomes, and research and were asked in the form of yes-or-no questions.

Historically, have women been included in research?

Is there a difference between sex and gender?

Do sex and gender matter in disease diagnosis, manifestation, course, and treatment?

Are you aware of the sex and gender differences in the symptoms of cardiovascular disease (CVD) based on gender?

Are you aware of the sex and gender differences in the transmission of sexually transmitted infections?

Do sex and gender matter in response to pharmaceuticals?

Are you aware of the National Institutes of Health Women's Health Electronic Resource?

Additionally, the posttest captured comments from the participants regarding what they learned.

RESULTS/FINDINGS

The present pilot project was conducted to increase the awareness of sex and gender differences in women's health, research, and health outcomes. SCHP collaborated with Womb Work to increase the awareness of women's health and the importance of sex and gender differences in disease manifestation, course, treatment, and outcomes. Their productions were tailored and designed to increase the awareness of specific issues (eg, women are twice as likely as men to contract a sexually transmitted disease [STD]), relieve the stress of an unbalanced society (eg, through music and dance), and better understand social conditions as well as health disparities (eg, gender influences health). The WHISK Pilot Project team provided three educational sessions with Womb Work to provide state-of-art and evidence-based information on sex and gender differences research and women's health. Data were gathered from various PubMed peer-reviewed articles, consultations with the Society for Women's Health Research (SWHR), and the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH). Womb Work designed and implemented a creative arts and community-based theater performance entitled, “Do You Really Know About Sex and Gender Differences and Women's Health?”

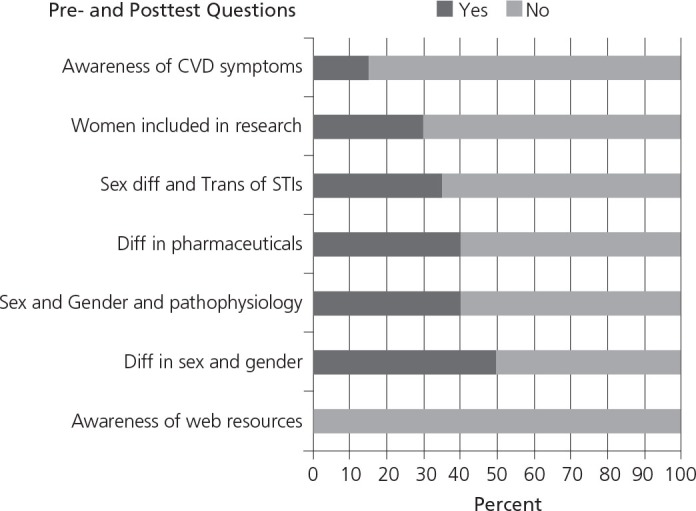

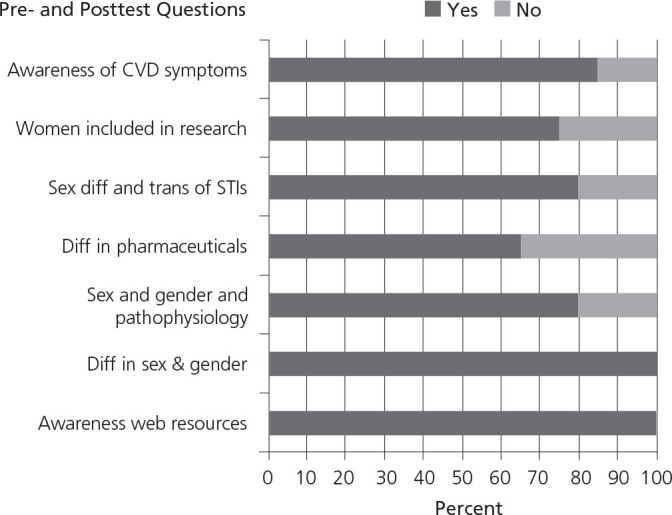

Given the promise of theater to provide new opportunities for the analysis, representation, and transfer of data/knowledge, health researchers have begun to show interest in performance art as a means of interpreting, enlivening, and enriching their findings.10 The Womb Work theater performance was informed as well as guided by the pretest/posttest questions to transfer knowledge through creative arts and theater expressions, thereby increasing the awareness of sex differences and enhancing the understanding of sex and gender differences in health and disease pathophysiology. Findings from the project are listed in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Pre-test results.

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; diff, difference; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; trans, transmission.

Figure 2.

Posttest results.

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; diff, difference; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; trans, transmission.

Of the participants, 78% (n=241) were not aware of sex and gender differences in women's health and disease manifestation. Although a few of the participants assumed that there are some differences relative to health based on sex, they still referred to women as small men. Based on the lack of awareness and knowledge relative to sex and gender differences in women's health, it is clear that there is a need to increase awareness among several populations (eg, medical students, health professionals, and consumers). Participants clearly articulated that they were not aware that women react differently to medications, are more vulnerable to certain diseases (eg, autoimmune diseases, osteoporosis, and HIV/sexually transmitted infections), and have different symptoms.

CVD is the primary cause of mortality for both men and women. Of the participants, approximately 85% (n=262) were unaware of the serious differences between men and women relative to CVD. Furthermore, participants were not aware that women are more likely than men to have more than one heart attack and that more than 50000 more women than men die from heart disease annually. Once again, participants referred to women as small men.

Of the participants, 65% (n=200) were not aware of the sex and gender differences that occur in relation to STDs. Roughly 35% of the participants were aware that women are two times more likely than men to contract an STD and that HIV is among the leading causes of death for US women.

Posttest data provide a clear picture that the goal of the WHISK Pilot Project was achieved. There was an increase in awareness and knowledge about sex and gender differences in women's health and disease manifestation among the participants. The areas with the greatest impact were women's experience of CVD and awareness of and access to the women's health electronic resources. Additionally, 85% of the participants gained knowledge and awareness of the diagnosis, course, and treatment of CVD among women. Furthermore, participants became aware of the symptoms of a myocardial infarction (eg, upper back pain, jaw pain, fatigue, and nausea) based on gender. All of the participants learned about the wealth of women's health electronic resources. Of note, the results of this project are subject to some limitations. Some of the participants did not participate in the community-based theater educational sessions.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings from the pretest/posttest data suggest that, after the training and community-based theatrical performances, participants demonstrated more knowledge of sex and gender differences in women's health and health outcomes and awareness of the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women's Health electronic resources. In all categories, there was an apparent change in increased knowledge. The smallest percentage change noted began at 50% (Question: Is there a difference between sex and gender) and improved to 100% (Question: Are you aware of the NIH Women's Health Electronic Resource?). The changes clearly illustrate the effectiveness of providing evidence-based and reliable information that also takes into account the culture and diversity of the participants.

One of the most important areas of increased knowledge was the inclusion of women in research. After the education training, 70% of the participants were aware that historically women had been banned from medical research (1977) due to thalidomide and diethylstilbestrol prescriptions. A substantial change in learning acquisition was related to the question about awareness of sex and gender differences in CVD symptoms. Initially, participants were not aware of the different symptoms of myocardial infarction based on gender. A participant noted on her posttest sheet, “I had no clue that unusual fatigue and nausea could be symptoms of a heart attack based on gender. All women should know this information. From now on, I will ask my doctors about differences for my health based on gender.” Differences in reactions to pharmaceuticals were another area with apparent change in increased knowledge. Prior to the posttest, 60% of the participants were not aware that the enzymes that metabolize certain drugs have different activity levels in women and men, so drugs are metabolized by these enzymes at different rates (women metabolize faster), which may cause more side effects in women than men. Sex and gender differences training and community-based theater revealed that women are not “small men.” Gender plays a role in health, and it cannot be assumed that a male model for health also applies to women.

DISCUSSION

When it comes to women's health, sex matters.15 Sex is a crucial biological variable that should be considered when designing and analyzing studies in all areas and at all levels of biomedical and health-related research.15 Sex differences of importance to health and human disease occur throughout the life span, although their specific expressions vary at different stages of life.16 According to the Institute of Medicine, sex affects health in all areas, including health promotion and disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.16 Though little can be done to change biological determinants of health, improving women's health requires recognizing and addressing gender differences as well as inequalities affecting women and girls of all ages.3 These topics must become a vital part of educational considerations.

Vast amounts of new scientific data, including information about sex and gender differences, are emerging and should be embedded into educational and training programs for all healthcare professionals. Translating new knowledge and scientific advances regarding sex differences will ultimately impact patient care, and men as well as women will receive the benefits. The barriers often found in understanding the terms sex and gender must be removed. Researchers and healthcare professionals must clearly understand that the terms are distinct and not synonymous. Every attempt to disseminate sex differences knowledge will benefit all. There should be various educational methods to address this very important discipline using creativity and new innovations for a new cadre of healthcare professionals.

The arts have been a catalyst for change and growth in a wide range of health-promotion activities, including awareness efforts. Theater holds great promise in the world of education and health-related translation of knowledge.10 By engaging audiences on a cognitive and sometimes emotional level and by using various forms of communication, theater has the potential to enhance complex dynamics,10 the awareness of social issues, and the understanding of crucial health messages. Through theater, women not only acquire new insights regarding sex and gender differences in health, health outcomes, and research but can have a better understanding of the role they play for patients and healthcare consumers.

The WHISK Pilot Project through creative arts and theater expressions enhanced knowledge of sex and gender differences in women's health, health outcomes, and research. A critical component of the learning exercise included sex and gender differences in myocardial infarction symptoms. Sex and gender differences in CVD have been well investigated and there is epidemiological evidence that men and women face different risks and have different outcomes.17 Through theater expression, women were able to not only see the symptoms of myocardial infarction played out but were also better able to understand the significance of CVD.

In general, pilot studies provide the researcher with ideas, approaches, and clues that may not have been foreseen before conducting the pilot study. However, while this pilot project was extremely valuable, we cannot ignore the limitations. Limitations of this pilot study include that it was not designed to be definitive or generalizable. Additionally, time was a limitation; the researchers had a limited amount of time to complete the project.

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by funding from the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women's Health and the National Library of Medicine Outreach and Special Populations Branch.

Disclosures The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and indicated no potential conflicts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Senie R. The epidemiology of women's health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochleitner M, Nachtschatt U, Siller H. How do we get gender medicine into medical education? Health Care Women Int. 2013;34(1):3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buvini'c MA, Medici A, Fernandez E, Torres AC. Gender differentials in health. In: Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2nd ed New York: Oxford University Press; 2006:195–210 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clayton JA, Joseph S. Why research sex differences and similarities? Med Phys. 2013;40(4):040403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller V, Rice M, Schiebinger L, et al. Embedding concepts of sex and gender health differences into medical curricula. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(3):194–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services Beyond women's health: incorporating sex and gender differences into graduate public health curricula. 2004. http://www.asph.org/userfiles/WomensHealth-FINAL.pdf Accessed August 14, 2013

- 7.Shive S, Morris M. Evaluation of the energize your life! Social marketing campaign pilot study to increase fruit intake among community college students. J Am Coll Health. 2006Jul-Aug;55(1):33–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camic PM. Playing in the mud: health psychology, the arts and creative approaches to health care. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(2):287–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boydell KM, Volpe T, Cox S, et al. Ethical challenges in arts-based health research. http://www.ijcaip.com/archives/IJCAIP-11-paper1.html Accessed August 14, 2013

- 10.Rossiter K, Kontos P, Colantonio A, Gilbert J, Keightley M. Staging data: theatre as a tool for analysis and knowledge transfer in health research. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(1):130–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faigin MA, Stein CH. The power of theater to promote individual recovery and social change. Psychiatr Serv. 2010March;61(3):306–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bochm A, Boehm E. Community theater as a means of empowerment in social work. J Soc Work. 2003;3(3):283–300 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michigan State University, University Outreach & Engagement Points of Distinction: a guide book for planning and evaluating quality outreach. 2009; http://outreach.msu.edu/documents/pod_2009ed.pdf AccessedAugust14, 2009

- 14.Smith A. Technology trends among people of color. Pew Research Center. 2010. http://www.pewinternet.org/Commentary/2010/September/Technology-Trends-Among-People-of-Color.aspx AccessedAugust14, 2013

- 15.Wider J, Greenberger P, Society for Women's Health Research The savvy woman patient: how and why your sex matters to your health. Sterling, VA: Capital Books; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine Exploring the biological contributions to human health: does sex matter? Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2003/Exploring-the-Biological-Contributions-to-Human-Health-Does-Sex-Matter/DoesSexMatter8pager.pdf AccessedAugust14, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regitz-Zagrosek V. Sex and gender differences in health. EMBO Rep. 2012; 13(7):596–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]