Abstract

Background:

The Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health (BIRCWH) program is a mentored institutional research career development program developed to support and foster the interdisciplinary research careers of men and women junior faculty in women's health and sex/gender factors. The number of scholars who apply for and receive National Institutes of Health (NIH) research or career development grants is one proximate indicator of whether the BIRCWH program is being successful in achieving its goals.

Primary Study Objective:

To present descriptive data on one metric of scholar performance—NIH grant application and funding rates.

Methods/Design:

Grant applications were counted if the start date was 12 months or more after the scholar's BIRCWH start date. Two types of measures were used for the outcome of interest—person-based funding rates and application-based success rates.

Main Outcome Measures:

Grant application, person funding, and application success rates.

Results:

Four hundred and ninety-three scholars had participated in BIRCWH as of November 1, 2012. Seventy-nine percent of BIRCWH scholars who completed training had applied for at least one competitive NIH grant, and 64% of those who applied had received at least one grant award. Approximately 68% of completed scholars applied for at least one research grant, and about half of those who applied were successful in obtaining at least one research award. Men and women had similar person funding rates, but women had higher application success rates for RoI grants.

Limitations:

Data were calculated for all scholars across a series of years; many variables can influence person funding and application success rates beyond the BIRCWH program; and lack of an appropriate comparison group is another substantial limitation to this analysis.

Conclusion:

Our results suggest that the BIRCWH program has been successful in bridging advanced training with establishing independent research careers for scholars.

Key Words: Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health (BIRCWH), sex, gender

摘要

背景: 开创女性健康的跨学科研究事业 (Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health, BIRCWH) 计划是一项指导式的机构研究事业发展计划,旨在支持和促进男性和女性初级研究工作者在女性健康和两性/性别因素领域的跨学科研究事业。申请并获得国立卫生研究院 (National Institutes of Health, NIH) 研究或事业发展经费的学者人数,即为一项衡量BIRCWH 计划是否成功达到目标的近似指标。

主要研究目标: 提供与学者表现的衡量标准相关的描述性数据- NIH经费申请和资助率。

方法/设计: 如果经费申请开始日期是在学者 BIRCWH 开始日期后的 12 个月或更晚时间,则该经费申请即可计算在内。为获得目标结果,我们使用了两种类型的衡量指标-人员资助率和申请成功率。

主要结果测量指标: 经费申请率、人员资助率和申请成功率。

结果: 截至 2012 年 11 月 1 日,已有四百九十三名学者参与 BIRCWH。在已经完成培训的 BIRCWH 学者中,有 79% 已申请了至少一 项竞争性的 NIH 经费,而在提出 申请的学者中,有 64% 已经获得 了至少一项经费授予。在已完成的 学者中,有大约 68% 申请了至少 一项研究经费,而在这些提出申请 的学者中,约有一半成功获得了至 少一项研究经费授予。男性学者和 女性学者的人员资助率相近,但就 R01 经费而言,女性学者的申请成 功率更高。

限制: 数据是针对多年来的所有 学者计算得出的;除了 BIRCWH 计 划之外,许多可变因素都能够影响 人员资助率和申请成功率;而且缺 少适当的对照群体是此项分析的另 一项本质缺陷。

结论: 我们的结果表明,BIRCWH 计划已经成功地将高级培训与创立 学者的独立研究事业联系在一起。

SINOPSIS

Antecedentes:

El programa Creación de Carreras de Investigación Interdisciplinaria sobre la Salud de las Mujeres (Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health, BIRCWH) es un programa tutorizado de desarrollo de carreras de investigadores institucionales desarrollado para apoyar y fomentar entre los miembros más jóvenes del personal docente, hombres y mujeres, las carreras de investigación interdisciplinaria en la salud de las mujeres y los factores de sexo y género. El número de docentes que solicitan y obtienen becas de los Institutos Nacionales de Salud (National Institutes of Health, NIH) para el desarrollo de la investigación y profesional constituye un indicador aproximado de si el programa BIRCWH tiene éxito en la consecución de sus metas.

Objetivo(s) principal(es) del estudio:

La presentación de datos descriptivos en una métrica de rendimiento académico —índices de solicitud de beca de los NIH y de financiación.

Métodos/Diseño:

Las solicitudes de beca se contabilizaron si la fecha de inicio se produjo con una antelación mínima de 12 meses posterior a la fecha de inicio del BIRCWH por parte de los docentes. Se utilizaron dos tipos de medidas para la variable de interés —índices de financiación por persona e índices de éxito por solicitud.

Criterios de valoración principales:

Solicitud de beca, financiación de la persona e índices de éxito de la solicitud.

Resultados:

A fecha 1 de noviembre de 2012 habían participado en el BIRCWH cuatrocientos noventa y tres docentes. El 79 % de los docentes del BIRCWH que acabaron su formación había solicitado al menos una beca competitiva de los NIH, y el 64 % de los que la solicitaron había recibido al menos una. Aproximadamente el 68 % de los docentes con la formación acabada solicitaron al menos una beca de investigación, y aproximadamente la mitad de quienes presentaron una solicitud obtuvieron al menos una beca de investigación. Los hombre y las mujeres tuvieron índices de financiación por persona similares, aunque las mujeres tuvieron índices de éxito en las solicitudes más altos para las becas R01.

Limitaciones:

Los datos se calcularon para todos los docentes a lo largo de una serie de años; hay muchas variables que pueden influir sobre la financiación por persona y los índices de éxito en la solicitud más allá del programa BIRCWH; y la falta de un grupo comparativo adecuado constituye otra importante limitación de este análisis.

Conclusión:

Nuestros resultados sugieren que el programa BIRCWH ha tenido éxito en la conexión de la formación avanzada con el establecimiento de carreras de investigadores independientes para los docentes.

INTRODUCTION

In partnership with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Institutes and Centers, the Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH) designed in 1999 and implemented in 2000 the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health (BIRCWH) program. The BIRCWH program is a mentored institutional research career development program developed to support and foster the interdisciplinary research careers of men and women junior faculty in women's health and sex/gender factors by providing them with 75% protected time to conduct their research and by pairing them with senior investigators in a mentored, interdisciplinary scientific environment. The overarching goal of the BIRCWH program is “to promote the performance of research and transfer of findings that will benefit the health of women.”1 The program is built around three pillars: interdisciplinary research, strong mentoring, and career development.

The BIRCWH is a collaborative effort that spans multiple NIH Institutes and Centers. The first request for applications (RFA) was issued in 1999, and the sixth round of program funding was awarded in 2012 with co-funding by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of Mental Health. Each grant award is approximately $500 000 per year, the majority of which comes from ORWH but also includes support from several NIH Institutes and Centers as noted above.

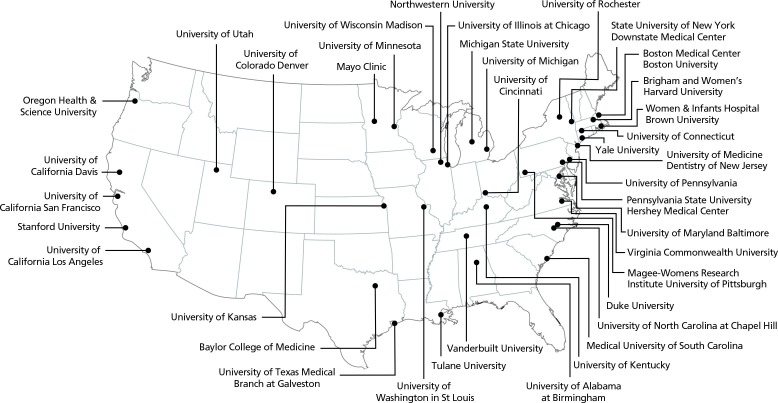

In fiscal year 2012, the BIRCWH program awarded more than $11 million to participating academic institutions, and over the past 12 years, the program has provided more than $88 million to develop researchers in women's health. To date, 77 BIRCWH awards have been made to 39 institutions in 25 states; 29 programs are currently active. The sixth round of BIRCWH awards brings the total number of ever-funded programs to 39 (Figure 1).

Figure.

Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health program sites, 2000–2012.

Because of its complexity, modern biomedical research increasingly must rely on teams of scientists who bring strengths and skills from a variety of disciplines. As research becomes increasingly formalized, it becomes truly interdisciplinary—research that integrates the analytical strengths of two or more often disparate scientific disciplines. By engaging seemingly unrelated disciplines, traditional gaps in terminology, approach, and methodology can be gradually eliminated. Removing these roadblocks can lead to a true collaborative spirit taking hold, thereby broadening the scope of investigations into biomedical problems, inspiring fresh and novel insights, and giving rise to new, analytically sophisticated “interdisciplines.”2

Drawing on multiple disciplines from its inception, the field of women's health research has been uniquely poised to promote and advance interdisciplinary research. Today's approach to research on women's health is to investigate sex/gender differences or similarities between women and men; the life span of women including reproductive-related health and menopause; and biological, behavioral, or other factors that result in health disparities among women.3 This broad conception of women's health research demands that basic scientists join with clinical researchers, social and behavioral scientists, health services researchers, and others to address far-reaching and complex questions affecting women's health.

The emphasis on interdisciplinary research is an innovative feature of the BIRCWH program. The BIRCWH program is open to individuals with a variety of backgrounds, training, and disciplines. BIRCWH scholars conduct basic science, clinical, translational, community-based, and health services research that spans the entire spectrum of women's health issues. While multidisciplinary research combines separate contributions from two or more disciplines, interdisciplinary research integrates the methods and concepts of multiple disciplines to better address problems whose solutions are beyond the reach of any single discipline.

Because of the focus on interdisciplinary research, a major goal of the BIRCWH program has been to bridge the transition to research independence for junior faculty to serve the ultimate goal of sustaining independent research careers in women's health. The number of scholars who apply for and receive NIH research or career development grants is one proximate indicator of whether the BIRCWH program is being successful in achieving its goals. This article presents descriptive data on one metric of scholar performance: NIH grant application and funding success rates.

METHODS

BIRCWH scholars and their dates of participation were identified from NIH electronic training appointment forms and annual grantee progress reports. Scholar characteristics, such as degrees and sex, were supplemented by Internet searches when they were not specified in the progress reports. Data on the BIRCWH scholars' subsequent grant applications and awards were obtained from the NIH Information for Management, Planning, Analysis, and Coordination (IMPAC II) database.4 IMPAC II contains details and documents for extramural applications and awards, and each applicant is assigned a unique identifier, which is linked to subsequent applications and awards. Scholars were matched to subsequent grants by the IMPAC II unique identifier. If multiple identifiers were associated with a BIRCWH scholar, all identifiers were used to ensure that the grant data are complete.

Grant applications were counted if the start date was 12 months or more after the scholar's BIRCWH start date. This was done to ensure that all applications counted reflect the impact of BIRCWH and not projects that were underway prior to the scholar's involvement in the BIRCWH program. Two types of measures were used for the outcome of interest: person-based funding rates and application-based success rates. For person-based funding rates, the person is the unit of analysis in both the numerator and the denominator. The person-based funding rate is calculated as the number of people who received grants divided by the number of people who applied. If a person submitted two grant applications and one was funded, this person's success rate was 100%. Application-based success rates are calculated as the number of awarded grants divided by the number of competitive applications. If a person submitted two grant applications and one was awarded, the application success rate would be 50%. For this reason, person-based funding rates will exceed application-based success rates.

Competitive grants include R, K, L, P, U, S, and DP series grants, among others. Research grants are defined as an NIH mechanism in the R, P, or U series, except for conference grants (R13 and U13), curriculum/educational development grants (R25), or dissertation awards (R36).

Differences between male and female BIRCWH scholars were compared using Fisher's exact test unless otherwise noted. All statistical analyses were completed with an online calculating web page (http://StatPages.org/ctab2x2.html), part of the StatPages Online Statistical Calculations website by John C. Pezzullo, Department of Medicine, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC.

RESULTS

Four hundred ninety-three scholars had participated in BIRCWH as of November 1, 2012 (Table 1). Of those, 123 scholars were active on that date. Although the award is open to both men and women, 80% of BIRCWH scholars have been women. Thirty eight percent of scholars have doctor of medicine (MD) degrees, 50% have doctor of philosophy (PhD) degrees, 11% have both MD and PhD degrees, and 1% of scholars have professional degrees such as doctor of pharmacy (PharmD), doctor of public health (DrPH), and doctor of veterinary medicine (DVM) degrees. Of the 335 scholars who completed their BIRCWH training, 120 (35.8%) were funded in the BIRCWH program for 2 to 3 years, 92 (27.5%) for 1 to 2 years, 92 (27.5%) for longer than 3 years, and the remainder (9.3%) were funded for 1 year or less.

Table 1.

Characteristics of BIRCWH Scholars

| Status | Men n (%) | Women n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active scholars | 18 (18.2) | 105 (26.7) | 123 (24.9) |

| Completed scholars | 69 (69.7) | 266 (67.5) | 335 (68.0) |

| Withdrawn | 12 (12.1) | 23 (5.8) | 35 (7.1) |

| All BIRCWH scholars | 99 (100.0) | 394 (100.0) | 493 (100.0) |

| Terminal Degree | |||

| MD | 34 (34.3) | 153 (38.8) | 187 (37.9) |

| PhD | 43 (43.5) | 204 (51.8) | 247 (50.1) |

| MD and PhD | 22 (22.2) | 32 (8.1) | 54 (11.0) |

| Other professionala | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.3) | 5 (1.0) |

| All BIRCWH scholars | 99 (100.0) | 394 (100.0) | 493 (100.0) |

Other professional degrees include PharmD, DrPH, DDS, and DVM.

Abbreviations: BIRCWH: Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health; DDS, doctor of dental surgery; DVM, doctor of veterinary medicine; DrPH, doctor of public health; MD, doctor of medicine; PharmD, doctor of pharmacy; PhD, doctor of philosophy.

Table 2 shows person-based application and funding rates for competitive NIH grants. As of November 2012, 79% of BIRCWH scholars who completed training had applied for at least one competitive NIH grant and 64% of those who applied had received at least one grant award. Women were more likely than men to apply for individual early career development (K series) grants (30.8% vs 8.7%, P < .001), but among those who applied, there were no statistically significant differences between women and men in funding rates.

Table 2.

Person-based NIH Competitive Grant Application and Funding Rates for All BIRCWH Scholars Who Completed Training by Sex and Grant Type

| Men | Women | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIRCWH scholars who completed training | 69 | 266 | 335 |

| Scholars with any competitive application | 51 | 214 | 265 |

| Scholars with any funded grant | 27 | 142 | 169 |

| Person application ratea | 73.9% | 80.5% | 79.1% |

| Person funding rateb | 52.9% | 66.4% | 63.8% |

| Scholars with K seriesc application(s) | 6 | 82 | 88 |

| Scholars with K series grant funded | 4 | 51 | 55 |

| Person application ratea | 8.7% | 30.8% | 26.3% |

| Person funding rate | 66.7% | 62.2% | 62.5% |

| Scholars with research grant application(s) | 48 | 180 | 228 |

| Scholars with research grant funded | 23 | 95 | 118 |

| Person application rate | 69.6% | 67.7% | 68.1% |

| Person funding rate | 47.9% | 52.8% | 51.8% |

| Scholars with R01 application(s) | 38 | 127 | 165 |

| Scholars with R01 grant funded | 14 | 55 | 69 |

| Person application rate | 55.1% | 47.7% | 49.3% |

| Person funding rate | 36.8% | 43.3% | 41.8% |

Significant difference for men vs women, P < .01.

Person funding rate = no. of scholars with funded grants/no. of scholars who applied.

Includes K01, K02, K07, K08, K22, K23, K25, K99.

Includes all R, P, and U series grants except R13, U13, R25, and R36.

Abbreviations: BIRCWH: Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Approximately 68% of completed scholars applied for at least one research grant, and just over half of those who applied were successful in obtaining at least one research award (n = 118, 51.8%). About half of all completed BIRCWH scholars applied for at least one R01 (research project) grant, and 42% of scholars who applied received at least one R01 award. There were no statistically significant differences between men and women in application or funding rates for research grants in general or for R01 awards in particular.

Table 3 displays the application-based success rates for competitive NIH grants. Fifty-five individual K series grants were awarded to scholars who had completed BIRCWH training at a success rate of almost 40%. For research grants, the overall success rate was 17.2%, with 210 successful applications of 1219 submitted. Men and women were equally likely to receive NIH funding when all research grants were considered, but R01 applications by women were more successful than those by men, with success rates of 19% and 12%, respectively (P < .05). The overall success rate for R01 applications was 17%.

Table 3.

Application-based NIH Competitive Grant Application and Success Rates for All BIRCWH Scholars Who Completed Training by Sex and Grant Type

| Men | Women | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| K seriesa grant submitted | 9 | 131 | 140 |

| K series grant funded | 4 | 51 | 55 |

| K series grant success rateb | 44.4% | 38.9% | 39.3% |

| Researchc grant submitted | 295 | 924 | 1219 |

| Research grant funded | 42 | 168 | 210 |

| Research grant success rate | 14.2% | 18.2% | 17.2% |

| R01 grant submitted | 165 | 496 | 661 |

| R01 grant funded | 19 | 92 | 111 |

| R01 grant success rated | 11.5% | 18.5% | 16.8% |

Includes K01, K02, K07, K08, K22, K23, K25, K99.

Application success rate = no. of funded grants/no. of applications.

Includes all R, P and U series grants except R13, U13, R25, and R36.

Significant difference for men vs women, P < .05.

Abbreviations: BIRCWH: Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

The person-based application and funding rates for completed BIRCWH scholars by sex and degree type are shown in Table 4. A higher percentage of women with an MD degree applied for and received funding than did men with an MD degree; however, that difference was not statistically significant. Completed scholars with PhD degrees were more likely to submit grant applications than those with MD degrees, Χ2 (2, N = 331) = 10.40, P <.01, 83% and 67%, respectively, yet the funding rate for those who applied was not significantly different between MDs and PhDs.

Table 4.

Person-based Application and Funding Rates for any NIH Fundinga for All BIRCWH Scholars Who Completed Training by Sex and Terminal Degree

| Men | Women | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD | Total | 20 | 109 | 129 |

| Applied | 10 | 77 | 87 | |

| Funded | 3 | 46 | 49 | |

| Application rate | 50.0% | 70.6% | 67.4% | |

| Funding rate | 30.0% | 59.7% | 56.3% | |

| PhD | Total | 33 | 129 | 162 |

| Applied | 29 | 106 | 135 | |

| Funded | 16 | 68 | 84 | |

| Application rate | 87.9% | 82.2% | 83.3% | |

| Funding rate | 55.2% | 64.2% | 62.2% | |

| MD and PhD | Total | 15 | 25 | 40 |

| Applied | 11 | 21 | 32 | |

| Funded | 6 | 12 | 18 | |

| Application rate | 73.3% | 84.0% | 80.0% | |

| Funding rate | 54.5% | 57.1% | 56.3% |

Excluding loan repayment awards.

Abbreviations: BIRCWH: Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health; MD, doctor of medicine; NIH, National Institutes of Health; PhD, doctor of philosophy.

Average time to funding for completed BIRCWH scholars varied somewhat by degree type, as shown in Table 5. On average, the time to funding was between 3 and 4 years for BIRCWH scholars of all degree types. Because of small cell sizes, it was not possible to compare men and women based on degree.

Table 5.

Average Time to Funding for All BIRCWH Scholars Who Completed Training by Terminal Degree, y

| Degree | Mean | standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All NIH grantsa | MD | 3.22 | 1.89 |

| PhD | 3.45 | 2.09 | |

| MD & PhD | 3.56 | 1.63 |

Excluding loan repayment awards.

Abbreviations: MD, doctor of medicine; PhD, doctor of philosophy.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that nearly 80% of BIRCWH scholars who have completed training have submitted at least one competitive application for an NIH grant. Of those who applied, almost two-thirds received at least one funded grant. Women were more likely than men to submit an application for a K series award; however, the funding rates for these applications were not different for men and women. Women in the BIRCWH program are at least as successful as men in obtaining NIH grants. For R01s in particular, person-based funding rates were higher for women than for men, although the difference was not statistically significant. In addition, R01 application-based success rates were significantly higher for women than men.

BIRCWH scholars with an MD degree applied for grants at a lower rate than their PhD-trained counterparts. This is likely the result of competing demands on clinician-scientists (MDs) that dedicated PhD researchers do not have to contend with. It is reassuring, however, that the funding rate for those who applied was not statistically significantly different between MDs and PhDs. The differences that we found in funding rates between men and women and in terms of scholars' degrees were largely due to differences in application rates. BIRCWH scholars who apply for grants get funded, and those who apply for more grants are more likely to get funded. Average time to NIH research funding varied somewhat by sex and degree type.

It is tempting to compare BIRCWH funding and success rates to overall NIH funding and success rates. However, comparisons are limited by a number of factors. Importantly, funding and success rates vary across years as the number of applications and amount of available funding change, as do the definitions and types of funding mechanisms available each year. In addition, new and established investigators have different success rates, as do various funding mechanisms. Finally, the characteristics of BIRCWH scholars are not necessarily congruent with the NIH investigator pool as a whole (eg, women are overrepresented in BIRCWH compared to NIH applications). Therefore, BIRCWH data is discussed here in the context of NIH data with the caveat that it is not strictly comparable.

More than one quarter of BIRCWH scholars have sought continued funding for their mentored research through individual K series applications. They have been very successful, with 39.3% of those K applications having been funded. During this same period (2002–2012), NIH-wide annual application success rates for Ks decreased from 46% to 32% (NIH Office of Extramural Research, 2013). For research project grants, BIRCWH scholars had an overall success rate of 17.2% and a 2012 success rate of 20.4%. NIH-wide success rates for 2002 to 2012 decreased from 30% to 18%.5 Thus, for 2012 at least, BIRCWH scholar success rates appear to be similar to NIH-wide rates.

A study by Jagsi et al reported that fewer than half of K08 and K23 recipients received R01 funding within 10 years of training and that women were less likely than men to receive an R01.6 However, the authors did not control for sex differences in application rates, which would likely have accounted for the sex differences in funding rates.7 A more recent study by Pohlhaus et al found higher R01 funding rates among a cohort of K01, K08, and K23 recipients (range 49%–60%) with no significant sex differences.8

The differences between these studies and the current study are likely due to methodology and timing. Pohlhaus et al selected a cohort consisting of 1 fiscal year (2000) and examined R01 applications and grants from the subsequent 8 years that began during the doubling of the NIH budget and the era of success rates exceeding 30% (1999–2003). Thus, all scholars had the same amount of time, which included a period where success rates were more favorable. Jagsi et al selected a multi-year cohort (1997–2003), a significant portion of whom also benefited from a period of higher success rates.

The BIRCWH scholars, in contrast, have a larger range of time since beginning the program (1–12 years), and 70% of them began after 2003 and have had to contend with a more competitive funding environment that has now dropped to less than 20%. In fact, BIRCWH scholars who began 8 or more years ago have a 47% R01 funding rate as compared to a rate of 42% for all completed scholars.

There are several limitations to this approach to evaluating the grant application, funding, and success rates of BIRCWH scholars. These data are calculated for all scholars across a series of years, and the distribution of scholars across time differs for every program. Further, many variables influence person funding and application success rates beyond the specifics of their BIRCWH program, including their field of research, variation in overall NIH success rates, and the distribution of the program cohort over time. The lack of an appropriate comparison group is another substantial limitation to this analysis.

It should also be noted that NIH funding is only one measure of success for BIRCWH scholars. Many scholars receive substantial awards from other sources, such as the American Cancer Society. Further research examining all sources of funding would provide a broader picture of BIRCWH scholar success.

CONCLUSION

ORWH developed the BIRCWH program as an answer to the dual need for women's health research and for career development programs. A key goal of BIRCWH is to promote sustained independent research careers. One measure of success for such training programs is the number of scholars who apply for and ultimately receive NIH funding as independent investigators. Our results suggest that the BIRCWH program has been successful in bridging advanced training with establishing independent research careers for scholars. Supported by the pillars of interdisciplinary research, a rigorous mentoring component, and career development,9–11 the program has produced more than 493 scholars so far, most of whom have succeeded in obtaining at least one additional NIH grant. BIRCWH is now serving as a model for interdisciplinary research and career development in women's health.

Though not the original intention, BIRCWH also provides a platform for women, in particular, to be professionally successful. Data suggest that women tend to leave the NIH-funded career pipeline at the transition to independence.12 However, the BIRCWH program appears to provide incentive and support for women to stay in academic careers.

Disclosures The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no potential conflicts.

Contributor Information

Joan D. Nagel, Office of Research on Women's Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, United States.

Abby Koch, Center for Research on Women and Gender, University of Illinois at Chicago, United States.

Jennifer M. Guimond, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, United States.

Sarah Glavin, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, United States.

Stacie Geller, College of Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, United States.

REFERENCES

- 1.Office of Research on Women's Health Building interdisciplinary research careers in women's health, RFA-OD-99-008. NIH Guide. 1999. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/rfa-od-99-008.html Accessed July 30, 2013

- 2.National Institutes of Health Research teams of the future. http://common-fund.nih.gov/researchteams/index.aspx Accessed July 30, 2013

- 3.Pinn VW. Research on women's health: progress and opportunities. JAMA. 2005;294(11):1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research, Electronic Research Administration IMPAC II: commons registered grantees. http://era.nih.gov/commons/quick_queries/ipf_com_org_list.cfm Accessed July 30, 2013

- 5.National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research NIH data book. http://report.nih.gov/nihdatabook/ Accessed July 30, 2013

- 6.Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Griffith KA, Rangarajan S, Ubel PA. Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(11):804–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pohlhaus JR, Jiang H, Sutton J. Sex differences in career development awardees' subsequent grant attainment [letter]. Ann Intern Med. 2010:152(9):616–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pohlhaus JR, Jiang H, Wagner RM, Schaffer WT, Pinn VW. Sex differences in application, success, and funding rates for NIH extramural programs. Acad Med. 2011;86(6):759–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domino SE, Bodurtha J, Nagel JD; BIRCWH program leadership. Interdisciplinary research career development: building interdisciplinary research careers in women's health program best practices. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20(11):1587–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guise JM, Nagel JD, Regensteiner JG. Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health directors. Best practices and pearls in interdisciplinary mentoring from Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health Directors. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2012;21(11):1114–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinn VW, Blehar MC. Interdisciplinary women's health research and career development. : Rayburn WF, Schulkin J, Changing landscape of academic women's health. New York: Springer; 2011:53–76 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ley TJ, Hamilton BH. The gender gap in NIH grant applications. Science. 2008:322(5907):1472–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]