Abstract

Neuritic sprouting and disturbances of calcium homeostasis are well described in epilepsy. S100β is an astrocyte-derived cytokine that promotes neurite growth and induces increases in levels of intracellular calcium in neurons. In sections of neocortex of surgically resected temporal lobe tissue from patients with intractable epilepsy, we found that the number of S100β-immunoreactive astrocytes was approximately threefold higher than that found in control patients (p < 0.001). These astrocytes were activated, i.e., enlarged, and had prominent processes. Temporal lobe tissue levels of S100β were shown by ELISA to be fivefold higher in 21 epileptics than in 12 controls (p < 0.001). The expression of the astrocyte intermediate filament protein, glial fibrillary acidic protein, was not significantly elevated in epileptics, suggesting a selective up-regulation of S100β expression. Our findings, together with established functions of S100β, suggest that this neurotrophic cytokine may be involved in the pathophysiology of epilepsy.

Keywords: S100, Glial fibrillary acidic protein, Astrocyte, ELISA, Immunohistochemistry, Epilepsy

Epilepsy is characterized by neuronal injury, with neuritic sprouting and disturbances of calcium homeostasis (Margerison and Corsellis, 1966). However, there has been little attention focused on the potential neuromodulating role of astrocytes, and the cytokines they synthesize and release, in the pathophysiology of these alterations. In particular, S100β, an abundant astrocyte-derived cytokine (Van Eldik and Zimmer, 1988; Donato, 1991; Hilt and Kligman, 1991), has the following functions that suggest its relevance to the pathophysiology of epilepsy: (1) S100β is important in development (Bhattacharyya et al., 1992; Sarnat, 1992), (2) the biologically active S100β homodimer is a trophic factor for neurons, enhancing neuron survival and neurite outgrowth (Kligman and Marshak, 1985; Winningham-Major et al., 1989; Marshak, 1990; Hilt and Kligman, 1991; Barger et al., 1992; Bhattacharyya et al., 1992), (3) S100β stimulates increases in intracellular free calcium levels (Barger and Van Eldik, 1992), and (4) S100β also induces proliferation and affects the morphology of astrocytes (Selinfreund et al., 1990, 1991). In contrast to these beneficial actions, overexpression of S100β may have deleterious consequences, including excessive growth of dystrophic neurites. For instance, the levels of biologically active S100β homodimer are elevated in the activated astrocytes associated with dystrophic neurites in the neuritic plaques in Alzheimer’s disease (Marshak et al., 1992), and this overexpression has recently been implicated in the genesis of these neuritic plaques (Sheng et al., 1994b).

As a first step toward assessing the potential role of S100β in temporal lobe epilepsy, we quantified the number of S100β-immunopositive (S100β+) astrocytes and determined tissue S100β levels in resected temporal lobe samples from patients with intractable complex partial seizures. For comparison, we also determined the immunohistochemical staining pattern and tissue levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), an astrocytic intermediate filament protein (Eng, 1985).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient information

Temporal lobe samples from 44 patients were studied. Twenty-six of these patients had intractable temporal lobe epilepsy that was resistant to conventional drug therapies. Of these epileptics, five were excluded as explained below. After temporal lobe resection, 57% were free of disabling seizures (Engle classification I, Engle et al., 1993) and an additional 31% only rarely had disabling seizures (Engle classification II) within 12–27 months after surgery, and there was no mortality or major postsurgical morbidity in this patient group. Temporal lobe neocortical samples, collected postmortem, from 18 patients (15 males and three females) with no known neurological diseases were used as controls. The average postmortem interval was 10 h (range, 2–20 h). Routine neuropathological examination of tissue sections of temporal lobe neocortical samples from the selected epileptics showed no pathologic changes or only mild gliosis, and those from controls showed no pathologic changes. Sections from the hippocampal formation of the epileptics showed various degrees of gliosis. The five excluded patients had distinct, identifiable neuropathological abnormalities other than gliosis (three low grade gliomas, one metastatic carcinoma, and one cystic encephalomalacia secondary to remote encephalitis). Exclusion of these five patients left 21 epileptics (13 males and eight females; mean age, 26 years; median age, 22 years; age range, 9–45 years) and 18 controls (median age, 46 years; mean age, 45 years; range, 9–79 years) in the study.

Tissue preparation

Samples of temporal lobes were fixed in neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at a thickness of 10 μm, and prepared for immunohistochemical analysis using our previously published techniques (Griffin et al., 1993). Adjacent samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen for ELISA, western immunoblot analysis, and protein assays. Frozen tissue samples, weighing ~250 mg, were diluted in 4 volumes of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and homogenized as previously described (Griffin et al., 1993).

Antibodies and purified proteins

Rabbit antibodies selective for the S100β polypeptide were produced as previously described (Van Eldik and Griffin, 1994). These antibodies react selectively with S100β as ascertained by multiple criteria (western immunoblots, ELISA, radioimmunoassay, and immunohistochemistry) and are now available commercially (RaS100b; East Acres Biologicals, Inc., Southbridge, MA, U.S.A., and Swant Antibodies, Bellinzona, Switzerland).

Rabbit anti-bovine GFAP, mouse anti-human GFAP, and rabbit anti-bovine S100 were obtained from DAKO Corp. (Carpinteria, CA, U.S.A.). Purified GFAP was obtained from ICN Biomedicals Inc. (Costa Mesa, CA, U.S.A.). Recombinant S100β was purified as previously described (Van Eldik et al., 1988).

Immunohistochemical reaction and quantitation

Tissue sections were immunoreacted either individually for S100β or GFAP, or simultaneously for S100β and GFAP using a Doublestain Kit-System TM (DAKO), as previously described (Griffin et al., 1993). Sections were exposed to polyclonal anti-S100β at 1:300 and/or monoclonal anti-GFAP at a dilution of 1:300. Tissue sections from patients and controls were treated identically and in the same dish. The sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. The number of S100β+ and GFAP+ cells in temporal lobe sections from nine epileptics (six males and three females; mean age, 23 years; median age, 21 years; age range, 10–41 years) and six control patients (six males; mean age, 35 years; median age, 35 years; age range, 9–50 years) were counted at a magnification of 250 diameters in five microscopic fields of gray matter in each case.

Protein assay

Either the method of Lowry et al. (1951) or the Micro BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, U.S.A.), adapted to microtiter plates (Griffin et al., 1993), was used to determine protein concentrations based on standard curves generated using purified bovine serum albumin. The protein content of supernatants of tissue homogenates from surgical and postmortem specimens was ~1.5–3 mg/ml.

ELISA and quantitation

S100β and GFAP ELISAs were performed according to previously published protocols (Griffin et al., 1993). In brief, microtiter plates were coated with capture antibody (either rabbit anti-S100β or rabbit anti-GFAP) overnight at 4°C. After blocking for nonspecific binding, either purified S100β, GFAP, or tissue sample was added to the wells. After washing, plates were incubated with detecting antibody (biotinylated anti-S100β or anti-GFAP antibody). Plates were then washed, incubated with avidin-conjugated horse-radish peroxidase (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.), and washed again. Color development was with o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride substrate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). The optical density (OD) at 492 nm was measured spectrophotometrically on a microtiter plate reader (Bio-Rad model 450). The OD values were corrected by subtracting the background OD of wells receiving everything but antigen. The standard curves were drawn as corrected OD (linear on vertical axis) versus concentration of purified S100β or GFAP (logarithmic on horizontal axis). The final concentration of S100β or GFAP in test samples of brain tissue was calculated as nanograms per milliliter of tissue supernatant. Statistical analyses software (SAS) and ANOVA were used for data analyses. These analyses were performed on all 21 epileptic patient samples and on 12 control samples (nine males and three females; mean age, 55 years; median age, 61 years; age range, 10–79 years).

In vitro modeling of postmortem changes

To assess the possibility that postmortem changes might influence protein or S100β levels in supernatants, we measured total protein and S100β levels in supernatants from samples of temporal lobe from six epileptics, after the supernatants were incubated at room temperature for intervals from 0 to 24 h. The levels of total protein were measured using the microanalysis system described above. Levels of S100β were determined by ELISA as described above.

RESULTS

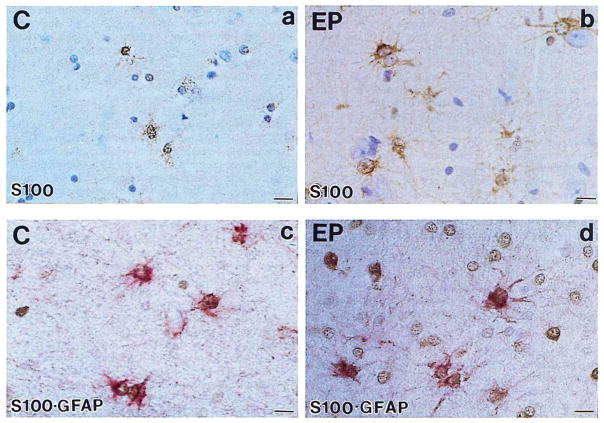

Immunohistochemical localization of S100β in temporal lobe tissue sections from epileptics demonstrated (Fig. 1) that S100β+ cells were enlarged, i.e., activated (da Cunha et al., 1993) astrocyte-like cells that were more intensely immunoreactive than their smaller counterparts in sections from controls (compare Fig. 1a and b). Dual immunohistochemical staining showed that almost all S100β+ cells were also GFAP+ in controls (Fig. 1c). In epileptics, most of the GFAP+ cells were also S100β+, although S100β-immunoreaction product could not be discerned in a few extremely large, intensely GFAP+ astrocytes located in superficial layers of cortex. In contrast, many of the S100β+ cells in epileptics were not detectably GFAP+ by dual immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 1d). S100β+ cells in epileptics resembled process-bearing activated astrocytes morphologically (Fig. 1b) and lacked expression of immunohistochemical markers for neurons, microglia, or oligodendrocytes (data not shown), suggesting that these S100β+ cells are indeed astrocytes.

FIG. 1.

Localization of S100β and GFAP in cells of temporal lobe tissue sections from epileptic and control patients by single and dual immunohistochemical staining. Temporal lobe sections from control (C) and epileptic (EP) patients were tested for S100β immunoreactivity (a, b) or simultaneously for S100β and GFAP immunoreactivity (c, d). S100β immune reaction product is brown; GFAP immune reaction product is red. Bar = 15 μm.

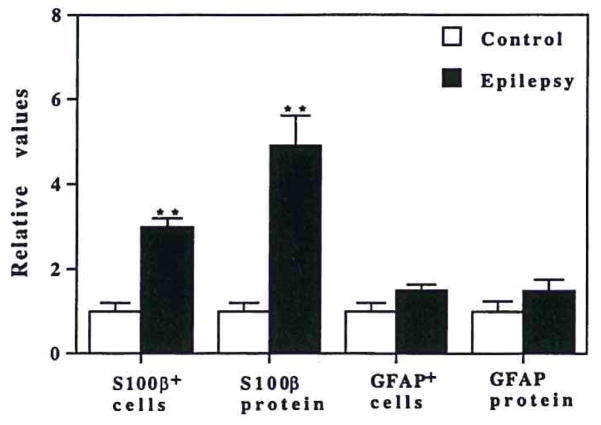

The observed increase in the number of S100β+ cells in immunohistochemically stained sections was quantified by counting the number of these cells, as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 2, S100β+ cells in sections from epileptics were three times as numerous as in sections from controls (p < 0.001). In contrast, the number of GFAP+ cells was not significantly increased in epileptics compared with controls (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Number of S100β+ and GFAP+ cells and tissue content of S100β and GFAP in temporal lobe from epilepsy and control patients. The numbers of S100β+ and GFAP+ cells were determined in temporal lobe sections from control (open columns) and epilepsy (EP; filled columns) patients as described in Materials and Methods. S100β and GFAP tissue levels were measured by ELISA in supernatants derived from temporal lobe homogenates from control (open columns) or epilepsy (EP; filled columns) patients. The data have been normalized relative to control values. Control cell counts were 48 ± 6 S100β+ and 23 ± 8 GFAP+ cells per square millimeter, and control protein values were 389 ± 106 ng S100β and 4,800 ± 200 ng GFAP per milliliter (all values are means ± SEM). **Values are significantly different from control (p < 0.001).

To determine whether the increase in number of S100β+ cells is reflected in quantitative changes in tissue S100β levels in epilepsy, we measured S100β and GFAP levels by ELISA. As previously shown (Van Eldik and Griffin, 1994), our S100β ELISA (Griffin et al., 1993) shows a linear standard curve from ~0.2 to 5 ng/ml S100β, and demonstrates <0.5% reactivity with the highly related S100α polypeptide and no detectable reactivity with calmodulin. The GFAP ELISA standard curve is linear from ~5 to 100 ng/ml. Determination of S100β levels in temporal lobe homogenates from epileptic and control tissue demonstrated a fivefold increase in S100β in epilepsy (Fig. 2). The increase in S100β levels was apparent even in those patients with no discernible abnormalities on routine hematoxylin and eosin histopathological examination. These ELISA results were confirmed by western immunoblot analysis of temporal lobe supernatants (data not shown). In contrast to the increased levels of S100β in epileptics, the tissue levels of GFAP were not significantly increased in epileptics compared with controls (Fig. 2). In those epilepsy patients with histologically apparent gliosis, mean tissue levels of GFAP were somewhat higher than those in patients without gliosis; however, those mean values were not significantly different from the mean values of the controls (data not shown).

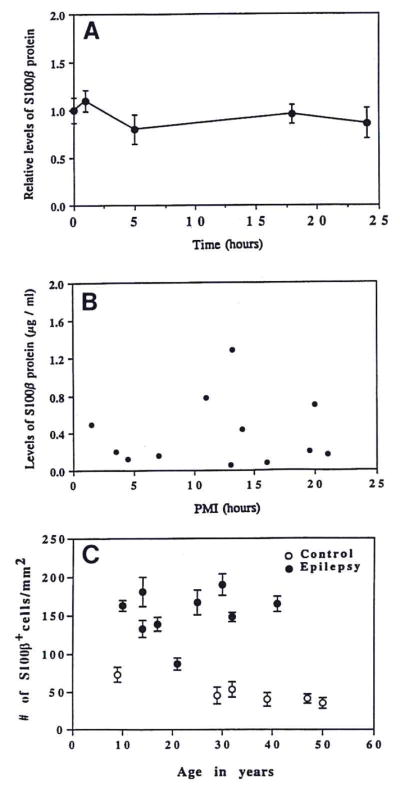

To address the possibility that the difference in S100β levels between epileptics and controls was because of protein instability (i.e., a potential loss of S100β in the samples due to time at room temperature or postmortem interval), we incubated epileptic tissue supernatants for various lengths of time at room temperature and then determined S100β levels by ELISA. There was no significant loss of S100β over a 24-h incubation period (Fig. 3A). In addition, tissue levels of S100β did not vary with postmortem interval in controls (Fig. 3B), nor did the number of S100β+ cells per square millimeter show any relation to epilepsy or control patient age (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

S100β tissue levels as a function of tissue incubation time or postmortem interval, and number of S100β+ cells as a function of patient age. A: Supernatants of tissue samples from six epilepsy patients were incubated at room temperature for various lengths of time, at which time S100β levels were measured by ELISA. The mean S100β levels ± SEM at the zero time point were normalized to 1.0 ± SEM and the S100β values at each time point thereafter were calculated relative to the zero time point. B: S100β levels in tissue supernatants from control patients were plotted as a function of the postmortem interval for each patient. C: S100β+ cells/mm2 in temporal lobe tissue sections from epilepsy and control patients as a function of patient age. Data shown as mean ± SD values for counts in five different microscopic fields of temporal neocortical gray matter. Neither postmortem interval, nor sample incubation time at room temperature, nor patient age was significantly related to S100β expression.

DISCUSSION

We show a selective, significant increase in the levels of the astrocyte-derived neurotrophic cytokine S100β in neocortical temporal lobe surgical specimens from patients with intractable epilepsy. The increase in tissue levels of S100β was significantly greater than the increase in number of S100β+ cells, suggesting an increase in cellular expression of S100β greater than the increase in number of S100β-expressing cells. The difference between S100β tissue levels in epileptics and controls is not likely attributable to postmortem changes in autopsy-derived control tissue because the levels of S100β in controls did not vary as a function of postmortem interval, and because incubation of homogenate supernatants of surgical specimens showed no significant loss of S100β over a 24-h period at room temperature. This conclusion is further supported by our previous finding that <0.5% total protein is lost per hour in similar incubations (Sheng et al., 1994a).

Epilepsy is a pathologic state in which inappropriate and excessive neuronal discharges occur in the brain with eventual neuronal loss (Menkes, 1985; Fisher, 1989). The role of astrocytes in this process has received little attention, despite the recognition that astrocytes may affect neurons directly through release of neurotrophic cytokines (Čarman-Kržan et al., 1991) or indirectly through the metabolic and regulatory functions that astrocytes provide for neurons. The selective increase in S100β levels shown here suggests several possible mechanisms for direct astrocytic involvement in epilepsy. The S100β homodimer is a neurite growth-promoting factor (Marshak, 1990) that has been shown to induce increases in intracellular free calcium concentration in both neurons and astrocytes (Barger and Van Eldik, 1992). It is possible that the abnormally high levels of S100β observed here in epilepsy could be directly detrimental to neurons by (1) induction of toxic increases in intracellular free calcium levels in neurons or (2) excessive trophic stimulation of neurite growth. S100β regulation of intracellular calcium levels may also affect astrocytes by possibly modifying the astrocytic calcium waves that occur during epileptic activity (Cornell-Bell et al., 1990). S100β-induced increases in astrocytic intracellular calcium levels may also indirectly affect neuronal calcium concentrations by interfering with astrocytic calcium-buffering functions.

The mechanism underlying the increase in S100β expression in epilepsy is unclear, but we favor induction by highly regulated feedback systems. The neurotransmitter serotonin, for instance, can induce release of S100β from astrocytes expressing serotonin 5-HT1a receptors (Whitaker-Azmitia et al., 1990) and S100β, in turn, can stimulate the growth of serotonergic neurites (Azmitia et al., 1990; Liu and Lauder, 1992). Serotonin has been shown to suppress neuronal activity in some animal models of epilepsy (Dubicka et al., 1978), suggesting that excessive astrocytic expression of S100β in human temporal lobe epilepsy may reflect a homeostatic attempt to suppress epileptic activity.

Our findings of elevated levels of S100β in epilepsy suggest that overexpression of this neurotrophic cytokine may be important in the brain’s response to the neuronal dysfunctions in epilepsy. This is further supported by the selectivity of the increase in S100β levels, i.e., the levels of GFAP were not elevated, a result that also suggests differential regulation of these two astrocyte proteins.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the original contributions of Dr. Laura Stanley and Paul Bean to these studies as well as the contributions of Drs. Stevenson Flanigan and Ossama Al Mefty. These studies were supported in part by NIH grant AG10208 (to L.J.V.E., R.E.M., and W.S.T.G.). We thank Ms. Sue Woodward for technical assistance and Ms. Pam Free for secretarial assistance.

Abbreviations used

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- OD

optical density

References

- Azmitia EC, Dolan K, Whitaker-Azmitia PM. S-100b but not NGF, EGF, insulin or calmodulin is a CNS serotonergic growth factor. Brain Res. 1990;516:354–356. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90942-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barger SW, Van Eldik LJ. S100β stimulates calcium fluxes in glial and neuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9689–9694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barger SW, Wolchok SR, Van Eldik LJ. Disulfide-linked S100β dimers and signal transduction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1160:105–112. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(92)90043-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya A, Oppenheim RW, Prevette D, Moore BW, Brackenbury R, Ratner N. S100 is present in developing chicken neurons and Schwann cells and promotes neuron survival in vivo. J Neurobiol. 1992;23:451–466. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Čarman-Kržan M, Vigé X, Wise BC. Regulation by interleukin-1 of nerve growth factor secretion and nerve growth factor mRNA expression in rat primary astroglial cultures. J Neurochem. 1991;56:636–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb08197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell-Bell AH, Finkbeiner SM, Cooper MS, Smith SJ. Glutamate induces calcium waves in cultured astrocytes: long-range glial signaling. Science. 1990;247:470–473. doi: 10.1126/science.1967852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Cunha A, Jefferson JJ, Tyor WR, Glass JD, Jannotta FS, Vitkovic L. Gliosis in human brain: relationship to size but not other properties of astrocytes. Brain Res. 1993;600:161–165. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90415-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato R. Perspectives in S100 protein biology. Cell Calcium. 1991;12:713–726. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(91)90040-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubicka I, Frank JM, McCutcheon B. Attenuation of a convulsive syndrome in the rat by lateral hypothalamic stimulation. Physiol Behav. 1978;20:31–38. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(78)90199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng LF. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP): the major protein of glial intermediate filaments in differentiated astrocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 1985;8:203–214. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(85)80063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle J, Jr, Van Ness PC, Rasmussen TB, Ojemmann LM. Outcome with respect to epileptic seizures. In: Engle J, editor. Surgical Treatment of the Epilepsies. Raven Press; New York: 1993. pp. 609–622. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RS. Animal models of the epilepsies. Brain Res Rev. 1989;14:245–278. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(89)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WST, Stanley LC, Yeralan O, Rovnaghi CR, Marshak DR. Methods for the study of cytokines in human neurodegenerative disease. Methods Neurosci. 1993;17:268–287. [Google Scholar]

- Hilt DC, Kligman D. The S-100 protein family: a biochemical and functional overview. In: Heizmann CW, editor. Novel Calcium-Binding Proteins. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1991. pp. 65–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kligman D, Marshak DR. Purification and characterization of a neurite extension factor from bovine brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:7136–7139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.20.7136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JP, Lauder JM. S-100 beta and insulin-like growth factor-II differentially regulate growth of developing serotonin and dopamine neurons in vitro. J Neurosci Res. 1992;33:248–256. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490330208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margerison JH, Corsellis J. Epilepsy and the temporal lobes. Brain. 1966;89:499–530. doi: 10.1093/brain/89.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshak DR. S100β as a neurotrophic factor. In: Coleman P, Higgins G, Phelps CH, editors. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Neuronal Plasticity in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Elsevier Science Publishers; Amsterdam: 1990. pp. 169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Marshak DR, Pesce SA, Stanley LC, Griffin WST. Increased S100β neurotrophic activity in Alzheimer disease temporal lobe. Neurobiol Aging. 1992;13:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(92)90002-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menkes JM. Paroxysmal disorders. In: Menkes JM, editor. Textbook of Child Neurology. Lea and Febiger; Philadelphia: 1985. pp. 608–671. [Google Scholar]

- Sarnat HB. Regional differentiation of the human fetal ependyma: immunocytochemical markers. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1992;51:58–75. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selinfreund RH, Barger SW, Welsh MJ, Van Eldik LJ. Antisense inhibition of glial S100β production results in alterations in cell morphology, cytoskeletal organization and cell proliferation. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2021–2028. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.5.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selinfreund RH, Barger SW, Pledger WJ, Van Eldik LJ. Neurotrophic protein S100β stimulates glial cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3554–3558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng JG, Boop FA, Mrak RE, Griffin WST. Increased neuronal β-amyloid precursor protein expression in human temporal lobe epilepsy: association with interleukin-1α immunoreactivity. J Neurochem. 1994a;63:1872–1879. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63051872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng JG, Mrak RE, Griffin WST. S100β protein expression in Alzheimer’s disease: potential role in the pathogenesis of neuritic plaques. J Neurosci Res. 1994b;39:398–404. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490390406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eldik LJ, Griffin WST. S100β expression in Alzheimer’s disease: relation to neuropathology in brain regions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1223:398–403. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eldik LJ, Zimmer DB. Mechanisms of action of the S100 family of calcium modulated proteins. In: Gerday C, Gilles R, Bolis L, editors. Calcium and Calcium Binding Proteins. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1988. pp. 114–127. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eldik LJ, Staecker JL, Winningham-Major F. Synthesis and expression of a gene coding for the calcium-modulated protein S100β and designed for cassette-based, site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:7830–7837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker-Azmitia PM, Murphy R, Azmitia EC. Stimulation of astroglial 5-HT1A receptors releases the serotonergic growth factor, protein S-100, and alters astroglial morphology. Brain Res. 1990;528:155–158. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winningham-Major F, Staecker JL, Barger SW, Coats S, Van Eldik LJ. Neurite extension and neuronal survival activities of recombinant S100β proteins that differ in the content and position of cysteine residues. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:3063–3071. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]