Abstract

Research links sex ratios with the likelihood of marriage and divorce. However, whether sex ratios similarly influence precursors to marriage—transitions in and out of dating or cohabiting relationships—is unknown. Utilizing data from the Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study (TARS) and the 2000 census, this study assesses whether sex ratios influence the formation and stability of emerging adults’ romantic relationships. Findings show that relationship formation is unaffected by partner availability, yet the presence of partners increases women’s odds of cohabiting, decreases men’s odds of cohabiting, and increases number of dating partners and cheating among men. It appears that sex ratios influence not only transitions in and out of marriage, but also the process through which individuals search for and evaluate partners prior to marriage.

Prior studies have found that the sex ratio, broadly defined as the ratio of males to females in a particular geographic unit, is associated with the likelihood of marriage and risk of divorce. These behaviors are the end result of a matching process whereby individuals search for, find, and evaluate current and potential partners—what Cherlin (2009) refers to as a coming and going of partners characteristic of intimate relationships in America. Research links marriage market characteristics to entry into and out of marriage (e.g., South and Lloyd 1992; Blau, Kahn, and Waldfogel 2000). A shortage of men relative to women in the marriage market has been associated with lower rates of marriage, higher rates of divorce, and higher rates of nonmarital child-bearing (Lichter et al. 1992; South and Lloyd 1992). The underlying explanation is that the sex ratio represents the availability of opportunities for individuals to form relationships (South, Trent, and Shen 2001; Fossett and Kiecolt 1991).

Despite evidence from these studies, research has yet to examine thoroughly the effect of sex ratios on behaviors preceding the decision to marry or divorce—e.g., transitions in and out of dating or cohabiting relationships—for both men and women. Furthermore, studies show the influence of neighborhood characteristics on nonmarital intimate behaviors of young adults, such as multiple and short-term sexual partnering and early parenthood (Billy and Moore 1992; Browning et al. 2008; South and Baumer 2000), but often ignore the effect of sex ratios. The current study bridges research on sex ratios and marriage with that on neighborhoods and emerging adult relationships by analyzing the effect of sex ratios on the formation and stability of nonmarital intimate relationships among young adults. This topic is particularly relevant for emerging adults because “[e]stablishing satisfying, long-term intimate relationships is one of the main challenges of early adulthood” (Amato and Booth 1997:84; Arnett 2004) given the role of dating (Longmore, Manning, and Giordano 2001) and cohabitation (Manning, Longmore, and Giordano 2007) in the progression of intimate unions. Because many determinants of union formation and stability vary between men and women (South and Crowder 2000; Teachman, Polonko, and Leigh 1987; Smock and Manning 1997), we explore differential effects of sex ratios using gender-stratified analyses. Our work reflects current family formation trends by relying on recently collected data, and extends past research examining neighborhood effects on young adult relationships by exploring the possible role of sex ratios.

BACKGROUND

Sex Ratios and Marriage: Union Formation and Dissolution

The marriage market is often characterized in terms of the sex ratio—the number of men relative to women (Fossett and Kiecolt 1991), representing the availability of opportunities for individuals to form relationships (South, Trent, and Shen 2001).1 One explanation for the effect of marriage market characteristics is the marital search model (Becker 1981; Oppenheimer 1988), which posits that individuals search for mates in specific areas, with the probability of marriage highest when the number of potential partners is greatest. Here, the sex ratio simply represents the availability of potential mates, and markets are deemed favorable or unfavorable based on the distribution of males and females in the population. A market characterized by an excess of women would be considered favorable for men, but unfavorable for women. The marital search process has been compared to job search processes, since both “…involve gathering information about the distribution of opportunities and then choosing the best available opportunity, given one’s own qualifications and attractiveness” (Harknett 2008:556). In unfavorable markets, because choices are limited, individuals may lower their standards for potential partners, prolonging (or postponing) entry into relationships. Studies examining women’s union formation behavior often support this explanation—in fact, most of the research on marriage markets focuses exclusively on women, although the search model predicts similar behavior for men and women. Consistent with a focus on the absolute availability of partners, these studies (e.g, Lichter, LeClere, and McLaughlin 1991; Lichter et al. 1992; South and Lloyd 1992) have found that shortages of men are associated with lower marriage rates, and a greater availability of men associated with higher rates of marriage.

An implicit assumption of the marital search perspective is that men and women equally value and seek out marriage. It posits a positive, linear relationship between the number of available partners and the odds of marriage. However, evidence suggests that women may have greater desires for marriage than men (Thornton and Young-Demarco 2001); thus, a second explanation for marriage markets—the imbalanced sex ratio perspective (Guttentag and Secord 1983)—is important to consider. This perspective applies a gendered lens to the effect of market characteristics, suggesting greater bargaining power for the sex in short supply, and focusing on conflicting goals between men and women (Guttentag and Secord 1983). Relationship formation is thus influenced by the sex with the greatest dyadic (and structural) power, as this facilitates the maximization of rewards and minimization of costs. For instance, because women are more often financially dependent on spouses, they may use their bargaining advantage (when they are in short supply) to marry higher-status mates. This perspective (like the marital search perspective) predicts a linear, positive effect of sex ratio on women’s likelihood of marriage (Kiecolt and Fossett 1997).

Conversely, given men’s weaker economic incentives to marry (Albrecht and Albrecht 2001), coupled with their desire to avoid or delay marriage, the imbalanced sex ratio perspective suggests that when men have bargaining advantage, there is less need for them to commit to relationships, and they experience a lower likelihood of marriage in favor of nonmarital relationships (Uecker and Regnerus 2010). Kiecolt and Fossett (1997) suggest men’s odds of marriage may be low in two circumstances: when women are plentiful, because men can secure sexual relationships without marital commitment, or when women are scarce, because men are constrained by fewer choices (drawing on the marital search model). Thus Kiecolt and Fossett (1997) posit a curvilinear effect of sex ratio on men’s odds of marriage, with marriage occurring most often among men in markets with balanced sex ratios, and least often when available partners are plentiful or scarce. Lloyd and South (1996:1099), however, interpret the imbalanced sex ratio perspective as suggesting that men’s odds of marriage are highest when women are scarce—in unfavorable markets, men are “motivated to commit to marriage in order to maintain a relationship with an opposite sex partner.” Therefore there may be a linear and negative effect of partner availability on men’s odds of marriage, with the odds highest when women are scarce and lowest when they are plentiful.

Despite these theorized differences in the effect of market characteristics on men’s and women’s behavior, few studies have empirically examined gender differences in the effect of sex ratios on union formation. Two studies by Fossett and Kiecolt (1990) Fossett and Kiecolt (1993) support the imbalanced sex ratio perspective at the aggregate level—the sex ratio was positively related to marriage for women, and showed a curvilinear pattern for men. Similarly, Albrecht and Albrecht (2001), using 1990 U.S. census data, found that the proportion of men married was lower in counties with a surplus of women compared to counties with more balanced sex ratios. It should be noted that all of these studies examined aggregate data from the U.S. census (as compared to individual-level data). The one study to examine sex ratio effects on men’s marital behavior at the individual level (Lloyd and South 1996) actually supported the marital search perspective, finding that men had higher odds of marriage in markets where women were plentiful (but this contradicted their imbalanced sex ratio perspective prediction that men’s marriage odds would be highest when women were scarce).

Both marital search and the imbalanced ratio perspectives suggest a linear, positive relationship between partner availability and women’s union formation behavior; therefore, the only way to distinguish the two perspectives is to examine men’s behavior, given the possible varied effects (negative and linear, curvilinear) of partner availability on men’s union formation. A contribution of the current study is that we explore the effect of sex ratios on the behaviors of women and men. Further, to date, there are no studies examining the effect of sex ratios on both men and women’s dating or sexual relationships—thus an additional contribution of this study is our focus on intimate relationships occurring prior to marriage.

While marriage market characteristics are important for entry in to marriage, they are also implicated in marital stability, as demonstrated in studies of divorce. Sex ratio explanations have been integrated into work on marital dissolution, with unbalanced sex ratios representing greater potential opportunities (i.e., spousal alternatives) for sexual infidelity, a strong predictor of divorce (e.g., Amato and Rogers 1997). Consistent with the exchange perspective (see, Sprecher 2001), past research shows that perceiving alternative partners is a risk factor for union dissolution (e.g., Felmlee, Sprecher, and Bassin 1990; Udry 1981), as is the actual availability of alternative partners (South and Lloyd 1995; McKinnish 2004; South, Trent, and Shen 2001). The sex ratio of one’s marriage market thus influences both the formation of new unions and the stability and dissolution of existing unions.

Romantic Relationships in Emerging Adulthood

Marriage is the capstone of a dynamic searching, sorting, and selecting process (Cherlin 2009), ubiquitous in the lives of adolescents and emerging adults. Dating, like cohabitation, are stages in these processes—what Guzzo (2006) calls the “relationship spectrum.” The formation of intimate relationships is an important life course process and a key developmental task during emerging adulthood (Meier, Hull, and Ortyl 2009; Arnett 2004; Amato and Booth 1997).

Because of the increasing age at marriage, a significant proportion of young adults have upwards of 10 years of relationship experience prior to marriage. Therefore, it is important to draw on recently collected data to explore the influence of sex ratios on relationship formation patterns.

Because of the rising prevalence of premarital cohabitation over the past several decades, many marriages involve a double selection process—selection into cohabitation then selection into marriage (Blackwell and Lichter 2000; Manning and Smock 2002). While most research on market characteristics focuses on marital behavior, two studies have tested the effect of sex ratios on cohabitation. Using data from the National Survey of Families and Households, Raley (1996) did not find a significant effect of mate availability on cohabitation. Guzzo (2006), analyzing women in the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth, found that greater availability of male partners was not associated with women’s odds of cohabiting compared to staying single. However, because both studies limited their analyses to women’s behavior, it remains unclear whether the sex ratio would similarly affect men’s decisions to cohabit.

Given that sex ratios influence marriage behaviors, and marriage is an end-stage of the dating process, we expect that sex ratios exert an effect earlier in the selection process, prior to marriage. Yet, research has not directly examined sex ratios and dating behavior among both men and women. Research examining neighborhood effects on young adult sexual and romantic relationship behavior has consistently found that disadvantaged neighborhoods, which often have fewer men relative to women, are characterized by multiple sexual partnering (by men) and early nonmarital fertility (e.g., South and Baumer 2000), consistent with the growing trend of non-relationship (e.g., “hook-up”) sex (Manning, Longmore, and Giordano 2005). This evidence is supportive of imbalanced sex ratio explanations if men, when in short supply, are delaying commitment to a single partner, as this would hinder their ability to have multiple sexual partners. It is noteworthy that although the imbalanced sex ratio perspective characterizes men as valuing sex over commitment, it is unknown if adolescent and young adult males hold similar values. In fact, recent research has documented that men are frequently as emotionally invested in relationships as females (e.g., Giordano, Longmore, and Manning 2006). Both the marital search and imbalanced sex ratio perspective assume that when women are the sex in short supply they are more likely to be in committed and cohabiting relationships, yet how mate availability affects premarital and nonmarital relationship behavior remains underexplored. Our work builds on and contributes to this research by directly considering how sex ratios influence dating and cohabitation among men and women in emerging adulthood.

CURRENT INVESTIGATION

Decisions about partnering with the opposite sex begin much earlier than decisions to marry. Drawing from the search and exchange perspectives, the current study broadens our understanding of how sex ratios influence relationship patterns in emerging adulthood. We assess whether two approaches to the sex ratio, the marital search perspective and the imbalanced sex ratio perspective, apply to young adult relationship patterns, examining two measures of relationship formation (currently in a romantic relationship, currently cohabiting) and three measures of stability (number of dating partners, relationship volatility, cheating), to assess whether partner availability, captured by the sex ratio, facilitates pre- and/or nonmarital union formation and stability among young adults, and whether these effects vary by gender.

We move beyond prior studies in five key ways. First, we extend past research by examining the effect of sex ratios on the dating and mating behavior of young adults; prior studies have not examined the effect of sex ratios on the relationship behavior of male and female emerging adults. Second, our study explicitly considers a key mechanism that is implicitly part of prior studies on marriage markets. Prior work implies that sex ratios influence marital dissolution because they signify “exposure” to relationship alternatives. We test if the sex ratio influences whether young adults have actually cheated on their romantic partner. Third, we extend our analyses to the relationship behaviors of both young women and men; the vast majority of past research has focused exclusively on women. Fourth, given the continued increase in the age at first marriage and growth in cohabitation, we draw on data collected in 2006, reflecting recent family formation trends. Finally, we include several measures associated with relationship formation and stability, such as attitudes and relationship commitment, to test whether sex ratios matter net of important individual and relationship characteristics.

DATA AND METHODS

The current study utilizes survey data from the Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study (TARS) merged with 2000 census data. TARS is a longitudinal study exploring adolescents’ and young adults’ relationships with parents, peers, and romantic partners and examining dating, cohabitating, and marital relationships in adolescence and emerging adulthood. The TARS has advantages over other datasets for this analysis. For example, because the majority of respondents reside in the greater Toledo Metropolitan Area, we can examine variation in the effect of sex ratios on patterns of behaviors occurring within a larger Labor Market Area (LMA). Additionally, while previous studies (e.g., South, Trent, and Shen 2001) analyzed the effect of sex ratios on the risk of divorce (South and Lloyd 1995), TARS directly asked respondents if they cheated on their dating partner. This allows us to explicitly gauge the impact of sex ratios on the mechanism (cheating) of union dissolution often implied in past research. This direct assessment of cheating is not available in other datasets examining adolescents and young adults, such as the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), which asks respondents if they suspected their partner had been sexually non-exclusive. Although previous analyses of Add Health (e.g., Ford, Sohn, and Lepkowski 2002) use respondents’ reports of the dates of their past sexual relationships to gauge concurrency, our direct measure is likely less subject to problems of recall bias.

The sample for the TARS was drawn from the enrollment records of registered students in the 7th, 9th, and 11th grades in Lucas County, Ohio (n = 1,321), a largely urban metropolitan area that includes the city of Toledo (students need not be attending school to participate). A stratified, random sample was obtained. Interviews were conducted primarily in respondents’ homes using laptop computers preloaded with the survey questionnaire. Respondents were ages 12–19 at Wave 1 (2001) and 17–24 at Wave 4 (2006). Respondents’ primary caregiver was also interviewed at Wave 1.

Contextual data from the 2000 U.S. census were appended to the TARS data. Respondents’ addresses were geocoded (physical addresses were matched to their corresponding block group and tract number) using GeoLytics® GeocodeDVD software. The current analyses use data from Wave 4, with contextual data matched to respondents’ Wave 4 residence, measured at the census tract level (n = 1,092). For conceptual clarity the analytic sample excludes married individuals (n=66; analyses including these respondents produced similar results), those who did not identify their sexual orientation as mostly heterosexual or 100% heterosexual (n=41)2, and six respondents residing on military bases (exclusion criteria not mutually exclusive), leaving 981 respondents. We then exclude an additional 24 respondents whose sex ratios were extreme outliers (discussed below). Survey questions about relationship stability were asked only of respondents who reported having a dating partner within the previous two years. Therefore, to maintain a consistent sample size across all analyses, we further subset the remaining 957 cases to the 876 respondents reporting dating during the past two years. We note that analyses executed on the full sample of respondents, where applicable, produced results similar to those presented below. Also, only 50 of the 957 respondents reported no dating experience—the sex ratio was not correlated with never dating (analysis not shown). Because listwise deletion is less likely than mean substitution to bias the sample when the proportion of missing information is low (Allison 2001), we also exclude 5 respondents missing information on key independent variables (discussed below). The final analytic sample includes 871 respondents (456 women, 415 men) across 226 census tracts, with an average of 4 respondents per tract.

Measures

Dependent variables

We analyze behavioral indicators of union formation (currently in a romantic relationship, currently cohabiting) and stability (number of dating partners, relationship volatility, cheating). Currently in a romantic relationship is a dummy variable coded 1 for respondents answering affirmatively to the question: “Is there anyone you are currently dating—that is, someone you like who likes you back?” (otherwise coded 0). We refer to this as currently in a romantic relationship, rather than currently dating, because the measure gauges union formation, and captures respondents who are dating as well as those cohabiting. Analyses assessing any relationship (during the past two years) and models excluding cohabiters produced substantively similar results; however, to maintain consist sample sizes across all models, analyses are executed on the analytic sample described above. Currently cohabiting is a dummy variable coded 1 for respondents currently living with a romantic partner (respondents who had never cohabited or were not currently cohabiting are coded 0).

Regarding union dissolution, number of romantic partners, a continuous measure, is the number of persons respondents reported dated during the past two years. Relationship volatility is the number of times respondents reported breaking up with their current or most recent romantic partner (note, this measure refers to break-ups with the same partner; one respondent missing this information was excluded from the analyses). Because these two measures were highly skewed, we truncated the values at their race- and gender-specific 95th percentiles. Cheating is based on responses to the question: “Since your relationship started, how often have you gotten physically involved (“had sex”) with other girls/guys?” Original response options (ranging 1 = never to 5 = very often) were collapsed into a dummy variable coded 1 for respondents indicating any frequency other than “never.”3

Independent variables

Our key independent variable is the sex ratio (SR)—the proportion of available partners in respondents’ immediate market, defined as their census tract. This is consistent with Fossett and Kiecolt’s (1991) characterization of marriage markets as local, and their note that individuals meet and choose potential mates from within their community (or a nearby community). Focusing on adolescents and young adults requires examining sex ratios in smaller units of analysis because their circles of interaction (e.g., social networks) are dense with age mates and smaller, compared to adults’ networks (e.g., counties or Labor Market Areas [LMA]). While census tracts may underbound the market for adults (Fossett and Kiecolt 1991), they may be a more appropriate unit of analysis for adolescents and young adults than the county or LMA.

Because there is no single established method for calculating the sex ratio, we explored several operationalizations, using theory and model fit to refine our measure. Based on the age of our sample and the range of dating partner ages (reported by respondents), we focused our sex ratio on the 16–34 year old age range—although our respondents were ages 17 to 24, approximately 9% of them reported a dating partner younger than 18 and about 15% reported a partner older than 24. Given that many prior studies on marriage markets have used race-specific sex ratios (Fossett and Kiecolt 1991; Harknett 2008; Lichter, LeClere, and McLaughlin 1991), we explored two possible calculations of a race-specific sex ratio, first limiting our analyses to Black and White respondents, and then using a sex ratio calculated separately for Whites and non-Whites (applied to the full analytic sample). Both measures were problematic—model fit was poor and in some models the estimates were unstable (models estimated extremely large confidence limits for the sex ratio coefficient). We believe model fit was compromised by race-specific sex ratios partly because the TARS data contain relatively few minorities (given the overall sample size), but more importantly, age-, gender-, and race-specific population sizes are at times not available in the census (Summary File 3) at the tract level. Cases were excluded from analyses if their tract-level race-specific population size was recorded as zero or missing, because their sex ratio could not be calculated. This was particularly problematic for non-White populations (age- and race-specific tract-level data were missing for 4.6% of Black respondents). Therefore, to retain as many cases as possible and maximize model fit, we use sex ratios that are not race-specific. This may be perceived as a limitation of our analyses, but we believe this is a reasonable approach, especially given that studies suggest less racial homophily in adolescent/young adult dating and cohabiting relationships than in marriage (Blackwell and Lichter 2000; Joyner and Kao 2005).

We modified the traditional sex ratio (the proportion of men to women) in order to facilitate simultaneous examination of men and women and directional consistency. In its original metric, the sex ratio ranges from 0 to 100, where smaller numbers mean greater numbers of women relative to men, (favorable markets for men), and 100 to positive infinity, with larger numbers indicating greater numbers of men relative to women, (favorable markets for women). This range has not been problematic for the vast majority of past research, which focuses on the behavior of either women or men; however, our analyses examine both women and men. Therefore, we calculated a sex ratio with directionally consistent scores reflecting partner availability for men and women—that is, a sex-specific sex ratio (SSSR). For women, partner availability is calculated as the traditional sex ratio: the proportion of males in the census tract age 16–34 to females in the census tract, age 16–34, multiplied by 100; but, the inverse of this formula is used to estimate available partners for males (the proportion of females relative to males).

This results in an indicator directionally consistent across gender; that is, higher scores of the sex-specific sex ratio (ratios of 100 and above) represent greater alternatives for both men and women. This means that males and females in the same neighborhood will have two different sex ratios, capturing the fact that the neighborhood is favorable for one group while simultaneously unfavorable for another group. For example, in a neighborhood where women outnumber men, female respondents have a SSSR of 74 (calculated as the traditional sex ratio), while male respondents in this same neighborhood have a SSSR of 135 (calculated as the inverse of the traditional sex ratio). Extreme outliers (values at or above the gender-specific 99th percentile and at or below the 1st percentile) were removed (so as not to bias the results), and the resulting measure ranges from 43.3 to 152.8, with a mean of 100.3. Supplemental analyses (not shown) excluding 5% and 10% of outlying cases produced results directionally and substantively similar to those presented below.

Readers may be concerned with the wide range in our observed measure of sex ratio. Such variation can be expected when analyzing data at a smaller unit of geographic analysis than previous studies—our tract-level measure will be more sensitive to variations than the Labor Market Area (LMA), which pools across tracts, potentially obscuring imbalance occurring at smaller units of analysis. The lowest (SSSR < 65) and highest (SSSR > 135) observed values of the sex-specific sex ratios occur for women and men, respectively, in particularly disadvantaged neighborhoods characterized by high proportions of Black residents, and with women outnumbering men. This is consistent with Wilson’s (1996) observation of racial segregation and concentrated poverty coupled with a lack of “marriageable men.”

As discussed above, one interpretation of the imbalanced sex ratio perspective suggests a curvilinear effect of sex ratio on men’s relationship formation behavior (Fossett and Kiecolt 1990; see also South and Lloyd 1995; South and Lloyd 1992). To test for this nonlinearity, our models include the sex-specific sex ratio squared. Because multicollinearity was problematic in models including both the sex ratio and its square, we grand mean-center the sex ratio (and square this mean-centered variable).

In addition to the sex-specific sex ratio, we also include several individual and relationship-specific characteristics that may be relevant for respondents’ relationship behavior. Respondents’ race/ethnicity is measured via dummy variables for Black, Hispanic, and Other (Asian, Pacific Islander, Alaskan Native) race, with White as the reference category. Age is a continuous measure ranging from 17–24.4 Since young adults may delay relationship formation because of other priorities such as work or school, we control for work status, measured by dummy variables for work (respondents who were working either full or part-time and not in school) and school (respondents who were in school and may or may not have been working). Respondents who were idle (neither working nor in school) are the reference category. Whether the respondent had a child is a dummy variable coded 1 for respondents who reported having a child at any wave and zero if childless. Respondents’ childhood family structure (at the baseline interview) is a series of dummy variables for two biological parents (reference), one biological parent, stepparent, and any other family structure. Mother’s education, derived from the wave 1 parent interview, is used as a proxy for respondents’ family of origin socioeconomic status. It is measured via dummy variables for less than high school and more than high school; a third dummy variable is included to retain respondents who were missing on this measure (n=72, 8.7%)—high school graduate is the reference category.

Respondents’ behaviors and attitudes about sex and sexual exclusivity may influence their relationship patterns, net of their dating/marriage markets. To control for this, we include measures tapping respondents’ religiosity, sexual impulsivity and cheating propensity. Religiosity is a summated scale of responses to four items (alpha = 0.79): “How often (during the past year) do you stop yourself from doing something you may want to because of your religious beliefs? …hang out with people from your church/religious group? …attend religious services? …pray?” (responses range from 0 = never to 4 = daily). Sexual impulsivity is a mean scale of responses to three items (alpha = 0.54): “I only have sex for fun” (responses range 0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree); “How often do you find yourself sexually attracted to someone you barely know?” (responses range 0 = never to 4 = very often); and “How important is it for you to be sexually exclusive (in general)?” (original response options reverse-coded to range from 0 = important to 4 = not important). Respondents were asked the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with nine hypothetical situations in which they might cheat on a romantic partner (e.g., “I might cheat on my partner if I no longer loved my partner, …my partner cheated first, …I was drunk or using drugs, …we had a fight,” etc.). Response options range from 0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree; cheating propensity is a mean scale of these nine items (alpha = 0.94). Although all twelve impulsivity and cheating items were correlated, a factor analysis indicated a two factor solution; therefore we retain the items as two separate scales.

We also control for romantic relationship quality in the analyses modeling relationship stability (number of dating partners, relationship volatility, and cheating) by including a scale assessing relationship commitment. This is a mean scale of the questions: “How often do you and your partner spend time alone in a typical week?” (responses range 0 = never to 3 = 5 or more times); “How important is your relationship with your partner?” (0 = not important to 4 = very important); and “In your relationship, how important is being faithful?” (0 = not important to 4 = very important) (alpha = 0.71). Four respondents missing information on these items are excluded from the analyses.

Certain neighborhood or tract-level characteristics may be associated with both skewed sex ratios and relationship formation/stability, thus rendering observed sex ratio effects spurious. As discussed above, research has found neighborhood disadvantage to be associated with multiple sexual partnering, non-relationship (“casual”) sex, early nonmarital fertility, and relationship instability (e.g., South and Baumer 2000). For robustness, our final models include a measure of tract-level neighborhood disadvantage—a mean scale of the proportion of female-headed households, households living below the poverty line, persons receiving public assistance, and the unemployment rate (alpha = 0.93).

Analyses

We use logistic regression to model current relationship status (dating, cohabiting) and cheating, Poisson regression for the number of respondents’ dating partners in the past two years, and negative binomial regression for the number of times respondents have broken up with a partner (because this measure is overdispersed). All analyses are stratified by gender and robust standard errors are used to adjust for clustering within census tracts. We estimate a marital search model (sex ratio only), an imbalanced sex ratio model testing for a nonlinear effect of the sex ratio (by including the sex ratio squared), and models combining sex ratio, sex ratio squared, and all individual, demographic, attitudinal, and neighborhood characteristics. We retain the squared form of sex ratio in the multivariate model only when tests revealed that the effect of sex ratio was nonlinear (which varied by gender for some models).

RESULTS

The sex-specific sex ratio, prior to mean-centering, has a mean of 95.31 for female and 104.82 for male respondents, indicating more favorable markets for men, in general. Sample descriptives are displayed in Table 1. The mean age of respondents is 20, and approximately 64% of respondents are White. Almost 25% of female and 14% of male respondents report having a child. Respondents, on average, score low on sexual impulsivity and cheating propensity, although men score higher than women on both scales. Women score slightly higher on relationship commitment.

Table 1.

Sample Descriptives, Percentages and Means (Standard Deviations), Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study (TARS), Wave 4a

| Full Sample (n=871) | Range | Females (n=456) | Males (n=415) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Independent Variables | ||||

| Market Characteristics | ||||

| Sex ratiob | 100.00 (14.63) | 43.25–152.83 | 95.31 (13.78) | 104.82 (14.02) |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | 13.39 (9.05) | 1.87–44.79 | 13.73 (9.39) | 13.01 (8.66) |

| Individual Characteristics | ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Agec | 20.33 (1.77) | 17–24 | 20.31 (1.81) | 20.33 (1.74) |

| Whited | 64.29% | 64.69% | 63.86% | |

| Black | 21.93% | 20.83% | 23.13% | |

| Hispanic | 10.33% | 10.53% | 10.12% | |

| Other race/ethnicity | 3.44% | 3.95% | 2.89% | |

| Has child | 19.29% | 24.34% | 13.73% | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Idled | 23.42% | 24.12% | 22.65% | |

| Working | 38.57% | 36.62% | 40.72% | |

| School | 38.00% | 39.25% | 36.62% | |

| Family Structure | ||||

| Two biological parentsd | 53.50% | 50.88% | 56.39% | |

| One biological parent | 24.34% | 25.00% | 23.61% | |

| Stepparent | 17.57% | 18.64% | 16.39% | |

| Other family structure | 4.59% | 5.48% | 3.61% | |

| Family Socioeconomic Status | ||||

| Mother < high school education | 8.96% | 9.43% | 8.43% | |

| Mother high school educationd | 29.39% | 30.26% | 28.43% | |

| Mother > high school education | 53.39% | 51.32% | 55.66% | |

| Missing mother education | 8.27% | 8.99% | 7.47% | |

| Attitude and Relationship Scales | ||||

| Religiosity | 4.51 (3.69) | 0–16 | 4.79 (3.70) | 4.20 (3.65) |

| Sexual Impulsivity | 1.02 (0.70) | 0–4 | .68 (0.49) | 1.39 (0.70) |

| Cheating Propensity | 1.20 (0.94) | 0–4 | .96 (0.85) | 1.47 (0.97) |

| Relationship Commitment | 2.96 (0.72) | 0–4 | 3.09 (0.67) | 2.82 (0.75) |

| Dependent Variables | ||||

| Union Formation | ||||

| Currently in romantic relationship | 68.77% | 75.00% | 61.93% | |

| Currently cohabiting | 20.21% | 24.34% | 15.66% | |

| Union Instability | ||||

| Number of dating partners | 2.25 (2.02) | 1–15 | 1.82 (1.11) | 2.73 (2.60) |

| Relationship volatility (break-ups) | 1.00 (1.29) | 0–5 | 1.00 (1.30) | 1.01 (1.28) |

| Cheated on partner | 18.14% | 13.60% | 23.13% | |

Notes

Ranges and standard deviations not shown for dummy variables.

For males, we use an inverse of the traditional sex ratio so that the measure is directionally consistent across genders, with high scores reflecting greater partner availability for both groups.

Variable is mean-centered in multivariate analyses.

Indicates reference category.

Three-quarters of women and 62% of men report currently being in a romantic relationship. One-fourth of women are currently cohabiting with a romantic partner, while only about 16% of men are cohabiting. Regarding union instability and dissolution, the mean number of dating partners during the past two years is 1.8 for women and 2.7 for men. Respondents broke up with their current or most recent romantic partner once on average. Approximately 14% of women and 23% of men cheated on their current or most recent partner.

The multivariate analyses assess how the sex-specific sex ratio affects young adults’ union formation and stability. We examine two measures of union formation: currently being in a romantic relationship and currently cohabiting. As Table 2 illustrates, the sex ratio does not influence the odds of currently being in a romantic relationship for men or women (the nonlinear term is also not significant and is not retained in the multivariate models). Older respondents are more likely than younger respondents to currently be in a romantic relationship. Black men, as well as men with children, have higher odds of being in a romantic relationship compared to White men and men without children. Sexual impulsivity is negatively related to relationship formation for both men and women.

Table 2.

Sex Ratio Imbalance and Union Formation: Currently in a Romantic Relationship, Odds Ratios

| Females (n=456) | Males (n=415) | |||||||

| Model 1A | Model 2A | Model 3A | Model 4A | Model 1B | Model 2B | Model 3B | Model 4B | |

| Intercept | 3.000*** | 2.941*** | 4.659*** | 5.339*** | 1.641*** | 1.591*** | 1.502 | 1.651 |

| Market Characteristics | ||||||||

| Sex ratioa,b | 1.004 | 1.004 | 1.006 | 1.011 | 1.013† | 1.012 | 1.010 | 1.005 |

| Sex ratio squaredc | 1.000 | — | — | 1.000 | — | — | ||

| Neighborhood disadvantage | — | 1.036* | — | 1.039* | ||||

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Ageb | 1.164* | 1.153† | 1.179* | 1.181* | ||||

| Black | .959 | .663 | 2.480* | 1.949* | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.075 | .900 | 2.586† | 2.306 | ||||

| Other race | 1.200 | 1.079 | .595 | .546 | ||||

| Has child | .206 | .768 | 3.220* | 3.057* | ||||

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Working | .510† | .555† | 1.008 | 1.059 | ||||

| School | .609 | .663 | .945 | .995 | ||||

| Family Structure | ||||||||

| One biological parent | 1.189 | 1.069 | .978 | .912 | ||||

| Stepparent | 1.361 | 1.257 | 2.225* | 2.192* | ||||

| Other family structure | 1.503 | 1.346 | .322 | .286† | ||||

| Family Socioeconomic Statusd | ||||||||

| Mother < HS education | .737 | .663 | .575 | .526 | ||||

| Mother > HS education | 1.100 | 1.119 | .613† | .617† | ||||

| Attitude Scales | ||||||||

| Religiosityb | .971 | .974 | .986 | .986 | ||||

| Sexual Impulsivity | .346* | .358* | .451* | 430* | ||||

| Cheating Propensity | 1.132 | 1.123 | 1.000 | 1.023 | ||||

| Log Likelihood | –256.29 | –256.24 | –241.63 | –239.55 | –274.33 | –274.20 | –242.55 | –239.85 |

Source: Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study (TARS), Wave 4

Notes

P < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001, two-tailed significance tests adjusted for clustering within census tracts

For males, we use an inverse of the traditional sex ratio so that the measure is directionally consistent across genders, with high scores reflecting greater partner availability for both groups.

Indicates variable is mean-centered.

Coefficient for sex ratio squared is only shown in models where it contributed significantly to the explanatory power of the model

Model also controls for missing mother’s education.

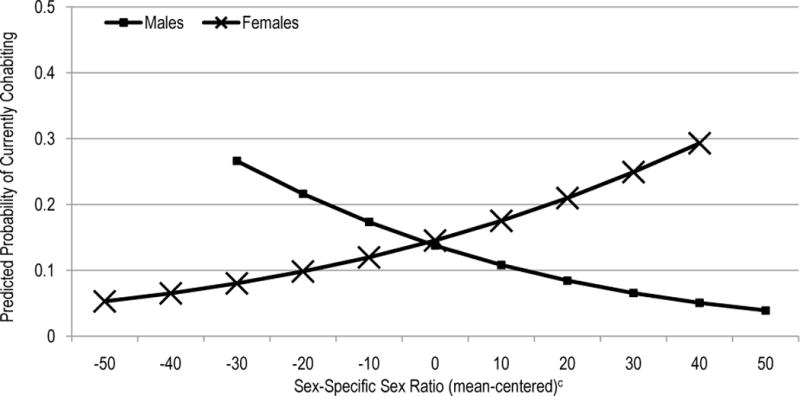

As Table 3 shows, the sex ratio does not influence the odds of currently cohabiting for women or men in the bivariate model (Model 1A). However, in the model controlling for individual characteristics (demographics and attitudes), the sex ratio is positively associated with the odds of cohabiting for women (Table 3, Model 3A) and negatively associated with the odds of cohabiting for men (Table 3, Model 3B). Women are more likely to cohabit in favorable markets while men are less likely to cohabit in favorable markets. This is consistent with the imbalanced sex ratio perspective, which posits that women are more likely to establish unions in markets where they are the sex in short supply and men are less likely to establish unions when in markets with greater partner availability. The squared term is not significant for either women or men, suggesting that the relationship between partner availability and odds of cohabiting is linear. This is consistent with our interpretation of the imbalanced sex ratio perspective, stated above. That is, if we recognize the conflicting goals between men and women regarding relationship formation, the association between partner availability and union formation for men may be the opposite of its effect for women—negative and linear (for men) compared to positive and linear (for women). This is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows that men’s odds of cohabiting are highest in markets least favorable to them (markets with more men than women) while women’s odds of cohabiting are highest in markets most favorable to them (markets with fewer women than men). Men’s odds of cohabiting decrease as their markets become more favorable (as the number of women relative to men increase). Conversely, women’s odds of cohabiting increase as their markets become more favorable. The effect of sex ratio does not become significant until the multivariate model (Models 3A and 3B); supplemental analyses indicated that age suppresses the effect of sex ratio, not surprising given that the odds of cohabitation is greater at older ages and sex ratio imbalance may increase with age, due to differential mortality and selective incarceration of males (particularly in disadvantaged neighborhoods). These relationships are robust to controls for neighborhood disadvantage (Models 4A and 4B), and consistent in analyses exploring the odds of ever cohabiting (not shown).

Table 3.

Sex Ratio Imbalance and Union Formation: Currently Cohabiting with Romantic Partner, Odds Ratios

| Females (n=456) | Males (n=415) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1A | Model 2A | Model 3A | Model 4A | Model 1B | Model 2B | Model 3B | Model 4B | |

| Intercept | .324*** | .296*** | .153*** | .170*** | .183*** | .198*** | .152*** | .160*** |

| Market Characteristics | ||||||||

| Sex ratioa,b | 1.010 | 1.010 | 1.019* | 1.023* | 0.990 | .992 | .977** | .973** |

| Sex ratio squaredc | 1.000 | — | — | 1.000 | — | — | ||

| Neighborhood disadvantage | — | 1.039† | — | 1.029 | ||||

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Ageb | 1.297*** | 1.299*** | 1.609*** | 1.637*** | ||||

| Black | .558 | .398* | 1.386 | 1.094 | ||||

| Hispanic | .881 | .762 | 4.066** | 3.737** | ||||

| Other race | .140 | .148 | 1.339 | 1.209 | ||||

| Has child | 3.784*** | 3.537*** | 3.353** | 3.197** | ||||

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Working | .993 | 1.059 | .663 | .716 | ||||

| School | .762 | .816 | .316* | .335* | ||||

| Family Structure | ||||||||

| One biological parent | 1.114 | .957 | 2.207† | 2.083 | ||||

| Stepparent | 2.960*** | 2.727** | 1.921† | 1.854† | ||||

| Other family structure | .748 | .619 | 1.205 | 1.266 | ||||

| Family Socioeconomic Statusd | ||||||||

| Mother < HS education | 1.070 | .927 | .411 | .386† | ||||

| Mother > HS education | 1.272 | 1.345 | .532† | .530† | ||||

| Attitude Scales | ||||||||

| Religiosity | .964 | .961 | .963 | .963 | ||||

| Sexual Impulsivity | .383** | .406** | .865 | .838 | ||||

| Cheating Propensity | 1.142 | 1.156 | .728 | .737 | ||||

| Log Likelihood | –252.25 | –251.21 | –210.86 | –208.76 | –179.49 | –179.04 | –140.06 | –139.17 |

Source: Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study (TARS), Wave 4

Notes

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001, two-tailed significance tests adjusted for clustering within census tracts

For males, we use an inverse of the traditional sex ratio so that the measure is directionally consistent across genders, with high scores reflecting greater partner availability for both groups.

Indicates variable is mean-centered.

Coefficient for sex ratio squared is only shown in models where it contributed significantly to the explanatory power of the model.

Model also controls for missing mother’s education.

Figure 1.

The Association Between Sex Ratio Imbalance and Currently Cohabiting, Among Young Adults, Predicted Probabilities by Gendera,bNotes:aEstimates taken from full models (4A and 4B, Table 3) with all other covariates held constant (dummy variables at zero and mean-centered continuous variables at their mean).bPlots based on gender-specific ranges of sex ratio that were observed in the data–these ranges differed by gender. cSex-specific sex ratio calculated as proportion of 16–34 year old males to females (for female respondents) and proportion of females to males (for male respondents).

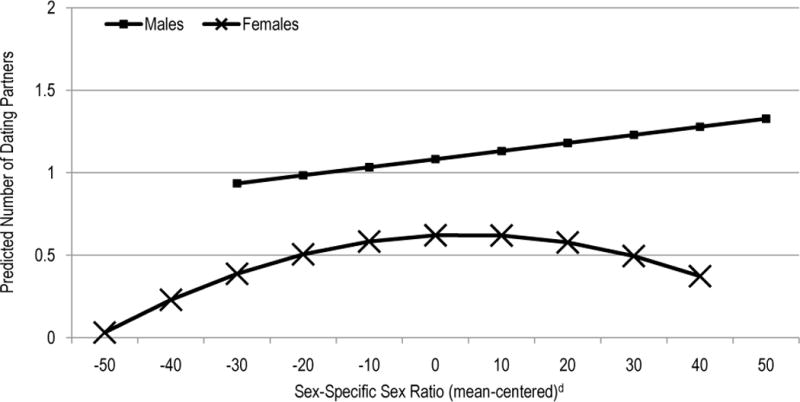

Regarding union stability, Table 4 shows no significant effect of sex ratio on the number of dating partners for women at the bivariate level; however, there is a small negative nonlinear effect in the multivariate model. This suggests that women’s number of dating partners increases along with the number of potential partners in their market up to a certain threshold point, at which their number of partners decreases as the market becomes more favorable—this is illustrated in Figure 2. Among male respondents, the effect of the sex-specific sex ratio on number of dating partners is linear, positive, and significant (Table 4, Model 3B), until neighborhood disadvantage is controlled (Model 4B, where significance of the sex ratio effect is attenuated to p = 0.10)—men have more dating partners in disadvantaged neighborhoods which tend to be favorable markets for them.

Table 4.

Sex Ratio Imbalance and Union Stability: Number of Dating Partner, Past 2 Years, Poisson Regression Coefficients

| Females (n=456) | Males (n=415) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1A | Model 2A | Model 3A | Model 4A | Model 1B | Model 2B | Model 3B | Model 4B | |

| Intercept | .597*** | .615*** | .617*** | .622*** | .992*** | .980*** | 1.606*** | 1.082*** |

| Market Characteristics | ||||||||

| Sex ratioa,b | .002 | .002 | .002 | .002 | .010** | .009* | .007* | .005 |

| Sex ratio squaredc | −.000 | −.0002** | −.0002** | .000 | — | — | ||

| Neighborhood disadvantage | — | .001 | — | .015** | ||||

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Ageb | −.025† | −.025† | −.111*** | −.108*** | ||||

| Black | .238** | .230* | −.066 | −.181 | ||||

| Hispanic | .147 | .144 | .310* | .279* | ||||

| Other race | −.066 | −.069 | −.416* | −.435* | ||||

| Has child | −.068 | −.068 | .005 | −.021 | ||||

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Working | .050 | .051 | −.035 | −.001 | ||||

| School | −.001 | .000 | −.077 | −.043 | ||||

| Family Structure | ||||||||

| One biological parent | .019 | .016 | .173 | .140 | ||||

| Stepparent | −.042 | −.044 | .143 | .124 | ||||

| Other family structure | −.243† | −.246† | .036 | .010 | ||||

| Family Socioeconomic Statusd | ||||||||

| Mother < HS education | −.131 | −.134 | –.274 | –.306† | ||||

| Mother > HS education | −.124† | −.123* | –.193 | .183 | ||||

| Attitude and Relationship Scales | ||||||||

| Religiosity | −.004 | −.004 | .010 | .009 | ||||

| Sexual Impulsivity | .132 | .131* | .165† | .152† | ||||

| Cheating Propensity | −.006 | −.006 | .156* | .167** | ||||

| Relationship Commitment | −.202*** | −.203*** | −.079 | −.091 | ||||

| Log Likelihood | –333.08 | –332.65 | –309.95 | –309.94 | 14.77 | 15.04 | 95.36 | 101.35 |

Source: Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study (TARS), Wave 4

Notes:

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001, two-tailed significance tests adjusted for clustering within census tracts

For males, we use an inverse of the traditional sex ratio so that the measure is directionally consistent across genders, with high scores reflecting greater partner availability for both groups.

Indicates variable is mean-centered.

Coefficient for sex ratio squared is only shown in models where it contributed significantly to the explanatory power of the model.

Model also controls for missing mother’s education.

Figure 2.

The Association Between Sex Ratio Imbalance and Number of Dating Partners Among Young Adults, Predicted Counts by Gendera,b,cNotes:aEstimates taken from full models (4A and 4B, Table 4) with all other covariates held constant (dummy variables at zero and mean-centered continuous variables at their mean).bPlots based on gender-specific ranges of sex ratio that were observed in the data–these ranges differed by gender.cSex-specific sex ratio significant for men at p = 0.10dSex-specific sex ratio calculated as proportion of 16–34 year old males to females (for female respondents) and proportion of females to males (for male respondents).

Table 5 shows that for women, the sex ratio is negatively associated with relationship volatility, and the effect is nonlinear (Table 5, Model 2A). Women break up with romantic partners less often when in favorable markets. The effect remains negative but is no longer statistically significant after controlling for demographics, attitudes, relationship characteristics (Model 3A), and neighborhood disadvantage (Model 4A). Further analyses (not shown) indicate that the effect of sex ratio on the relationship volatility can be explained by race—Black women are less likely to be in favorable markets but break up with their romantic partners more frequently. The sex ratio is negatively associated with relationship volatility among men (Table 5, Model 3B), but the relationship is attenuated (p = 0.14) when neighborhood disadvantage is added (Model 4B), which itself is negatively associated with relationship volatility. This may seem counterintuitive, given the positive association between sex ratio, disadvantage and number of dating partners among men (Table 4); however, this measure concerns breaking up (and potentially reconciling and breaking up again) with the same partner. In favorable markets, men may not break up and get back together with the same partner—they may simply break up and form a relationship with a new partner.

Table 5.

Sex Ratio Imbalance and Union Stability: Relationship Volatility (Number of Times Broken Up With Romantic Partner), Negative Binomial Regression Coefficients1

| Females (n=456) | Males (n=415) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1A | Model 2A | Model 3A | Model 4A | Model 1B | Model 2B | Model 3B | Model 4B | |

| Intercept | −.016 | −.070 | −.104 | −.107 | .008 | −.008 | −.658** | −.728*** |

| Market Characteristics | ||||||||

| Sex ratioa,b | −.010* | −.009* | −.004 | −.004 | −.004 | −.005 | −.008* | −.007 |

| Sex ratio squaredc | .0003* | −.000 | −.000 | .000 | — | — | ||

| Neighborhood disadvantage | — | −.001 | — | −.018* | ||||

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Ageb | .002 | .002 | −.009 | −.014 | ||||

| Black | .505** | .511** | .261 | .417* | ||||

| Hispanic | .271 | .273 | .004 | .038 | ||||

| Other race | −.104 | −.102 | .332 | .421 | ||||

| Has child | .101 | .102 | .270 | .301† | ||||

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Working | .028 | .027 | .261 | .224 | ||||

| School | −.209 | −.210 | .236 | .199 | ||||

| Family Structure | ||||||||

| One biological parent | .198 | .201 | .154 | .188 | ||||

| Stepparent | .195 | .196 | .286 | .320† | ||||

| Other family structure | −.122 | −.120 | .480 | .515† | ||||

| Family Socioeconomic Statusd | ||||||||

| Mother < HS education | .130 | .132 | .114 | .172 | ||||

| Mother > HS education | −.264† | −.264† | .247† | .254† | ||||

| Attitude and Relationship Scales | ||||||||

| Religiosity | −.001 | −.001 | .026† | .027† | ||||

| Sexual Impulsivity | .102 | .102 | .530*** | .561*** | ||||

| Cheating Propensity | .111 | .110 | −.082 | −.094 | ||||

| Relationship Commitment | –.012 | –.011 | .122 | .131 | ||||

| Log Likelihood | −413.77 | −412.77 | −392.19 | −392.19 | −385.82 | −385.74 | −361.08 | −359.70 |

Source: Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study (TARS), Wave 4

Notes:

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001, two-tailed significance tests adjusted for clustering within census tracts

For males, we use an inverse of the traditional sex ratio so that the measure is directionally consistent across genders, with high scores reflecting greater partner availability for both groups.

Indicates variable is mean-centered.

Coefficient for sex ratio squared is only shown in models where it contributed significantly to the explanatory power of the model.

Model also controls for missing mother’s education.

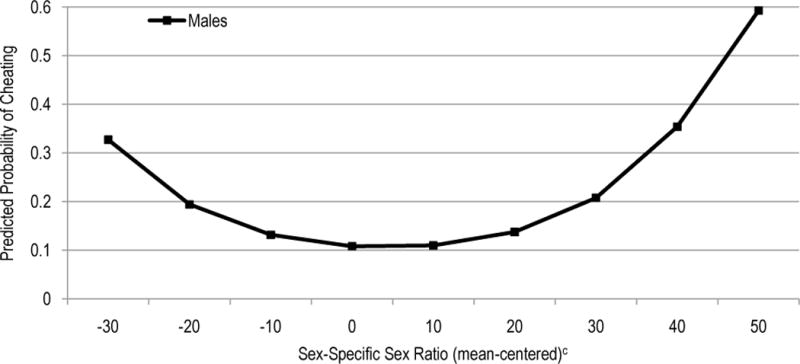

Lastly, for both men and women, cheating is highest when sex ratios are imbalanced—when alternative partners are extremely plentiful, or extremely scarce (Table 6, Models 2A and 3B). Among women, the effect of sex ratio on cheating is accounting for primarily by race and family structure (which attenuates the race effect, Model 3A). Among men, the effect of the sex ratio is suppressed by sexual impulsivity, relationship commitment, and being in school (Model 3B), and remains significant net of neighborhood disadvantage (Model 4B). Figure 3 illustrates the curvilinear effect of sex ratio on cheating among men. The odds of cheating are lowest when the sex ratio is just slightly above its mean, and increase as the imbalance increases. Neighborhood disadvantage has a marginal negative association (p < 0.10) with cheating among men. Sexual impulsivity and cheating propensity are positively associated with the odds of cheating for both men and women, and relationship commitment is negatively associated.

Table 6.

Sex Ratio Imbalance and Union Stability: Cheating on a Romantic Partner, Odds Ratios1

| Females (n=456) | Males (n=415) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1A | Model 2A | Model 3A | Model 4A | Model 1B | Model 2B | Model 3B | Model 4B | |

| Intercept | .158*** | .133*** | .060*** | .061*** | .301*** | .271*** | .140*** | .121*** |

| Market Characteristics | ||||||||

| Sex ratioa,b | 1.007 | 1.007 | 1.002 | 1.003 | 1.012 | 1.006 | .987 | .990 |

| Sex ratio squaredc | 1.001* | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.001 | 1.001* | 1.001* | ||

| Neighborhood disadvantage | — | 1.006 | — | .962† | ||||

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Ageb | 1.112 | 1.111 | 1.069 | 1.051 | ||||

| Black | 1.897 | 1.805 | 1.398 | 1.805 | ||||

| Hispanic | 2.691 | 2.638† | .799 | .853 | ||||

| Other race | .523 | .507 | 2.254 | 2.374 | ||||

| Has child | .439† | .441† | 2.730* | 2.930** | ||||

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Working | 1.157 | 1.165 | .620 | .584 | ||||

| School | .883 | .891 | .203** | .177** | ||||

| Family Structure | ||||||||

| One biological parent | 2.551** | 2.502** | 1.363 | 1.513 | ||||

| Stepparent | 2.506* | 2.478* | 2.689* | 2.924** | ||||

| Other family structure | .647 | .634 | 4.990† | 5.980† | ||||

| Family Socioeconomic Statusd | ||||||||

| Mother < HS education | 1.000 | .986 | 1.130 | 1.173 | ||||

| Mother > HS education | .839 | .843 | .929 | .926 | ||||

| Attitude and Relationship Scales | ||||||||

| Religiosity | 1.026 | 1.026 | 1.007 | 1.012 | ||||

| Sexual Impulsivity | 1.769† | 1.773† | 3.583** | 3.767** | ||||

| Cheating Propensity | 2.453** | 2.458** | 2.875** | 2.879** | ||||

| Relationship Commitment | .554* | .550* | .530** | .541** | ||||

| Log Likelihood | –181.11 | –178.752 | –139.40 | –139.364 | –223.31 | –222.20 | –130.65 | –129.49 |

Notes:

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001, two-tailed significance tests adjusted for clustering within census tracts

For males, we use an inverse of the traditional sex ratio so that the measure is directionally consistent across genders, with high scores reflecting greater partner availability for both groups.

Indicates variable is mean-centered.

Coefficient for sex ratio squared is only shown in models where it contributed significantly to the explanatory power of the model.

Model also controls for missing mother’s education.

Figure 3.

The Assocation Between Sex Ratio Imbalance and Cheating Among Young Adult Men, Predicted Probabilitiesa,bNotes:aEstimates taken from full model (4B, Table 6) with all other covariates held constant (dummy variables at zero and mean-centered continuous variables at their mean).bPlots based on gender-specific ranges of sex ratio that were observed in the data–these ranges differed by gender.cSex-specific sex ratio calculated as proportion of 16–34 year old females to males.

The increase in the odds of cheating with increases in available partners is consistent with the work of South and colleagues (1992); however, the increased odds of cheating in unfavorable markets may appear counterintuitive. Perhaps in markets with few alternatives, individuals may cheat on dating partners instead of ending an unsatisfactory relationship—that is, cheating may be part of the sorting, searching, and selecting process when individuals are faced with limited available partners. This could particularly be the case for young adults, given the developmental importance of romantic relationships in emerging adulthood. Additionally, unfavorable markets for one partner correspond to favorable markets for the other—cheating in an unfavorable market may occur in response (or retaliation) to having been cheated on by one’s partner (who faced a favorable market). Although we do not have information on the motivations for cheating (and therefore recognize these assertions as speculative), given the importance of romantic relationships during this life course stage, persons may wish to be romantically involved, but also remain active participants in their respective markets (Farber 1987; South, Trent, and Shen 2001). Individuals in constrained markets may remain interested in the few alternative partners available to them while simultaneously wary of ending an established relationship.

DISCUSSION

The present study explored the effect of sex ratios on the formation and stability of romantic relationships among young adult men and women. Our analyses were guided by two theoretical frameworks. The marital search model (Becker 1981; Oppenheimer 1988) posits that individuals search for mates in specific areas. The probability of marriage is highest when the number of available potential partners (the sex ratio) is greatest. This perspective assumes that men and women equally value and seek out marriage, and posits a positive, linear relationship between the number of available partners and the odds of marriage. The imbalanced sex ratio perspective, on the other hand, applies a gendered lens to the effect of market characteristics, suggesting greater bargaining power for the sex in short supply, and focusing on conflicting goals between men and women (Guttentag and Secord 1983). The sex with the greatest dyadic power (that is, the one in short supply) is able to navigate relationship formation and commitment. Both the imbalanced sex ratio and marital search perspectives predict a linear, positive effect of sex ratio on women’s likelihood of marriage (Kiecolt and Fossett 1997). However, according to the imbalanced sex ratio perspective, men’s marriage odds are low when women are plentiful, because men can secure sexual relationships without marital commitment (Kiecolt and Fossett 1997), and may actually be highest when women are scarce, because men may be motivated to commit in order to secure a relationship with an opposite sex partner (Lloyd and South 1996).

Our findings indicate that, among women, partner availability is associated with cohabitation and relationship instability. In favorable markets, women have higher odds of cohabiting; women report fewer partners in unfavorable markets, suggesting they are constrained by fewer opportunities, and report fewer partners in favorable markets, suggesting partner selectivity and greater stability in a particular relationship. These findings are consistent with the expectations of both marital search and imbalanced sex ratio perspectives, since both perspectives posit the same pattern of behavior among women. Among men, we find that partner availability is associated with lower odds of cohabitation, a greater number of dating partners, and fewer breakups and reconciliations with the same partner. When men are in favorable markets, they are less likely to commit to a cohabiting relationship, and are less committed to a single relationship. These findings are most consistent with the expectations of the imbalanced sex ratio perspective—when men are in short supply, they are able to avoid commitment.

The current analysis adds to past research focused primarily on the effects of sex ratios on the behavior of married individuals (e.g., South and Lloyd 1995). A key assumption of prior work is that imbalanced sex ratios influence union dissolution because these social contexts facilitate sexual infidelity. We explore these assumptions by focusing on the nonmarital unions formed by young adults and by measuring cheating behavior directly. Results indicate that imbalanced sex ratios are associated with cheating for men but not women. The curvilinear association between sex ratio and cheating is consistent with both marital search and imbalanced sex ratio perspectives. If we consider cheating indicative of low relationship commitment, men are likely to cheat—that is, they are less committed to a relationship—when partners are scarce (consistent with the marital search perspective). In favorable markets, men are also likely to cheat—consistent with the imbalanced sex ratio perspective. As we noted above, we cannot ascertain motivations for cheating. Perhaps given the importance of romantic relationships during emerging adulthood, young men may wish to be romantically involved, but also remain active participants in their respective markets (Farber 1987; South, Trent, and Shen 2001), or, individuals in constrained markets may remain interested in the few alternative partners available to them while simultaneously wary of ending an established relationship. Taken together, we find that sex ratios do matter and have effects on relationship formation and stability net of traditional predictors, often even net of contextual characteristics such as neighborhood disadvantage, and that the findings are most consistent with the expectations of the imbalanced sex ratio perspective.

It may be useful to include measures of sex ratio in future work on young adult relationship patterns. Additionally, future research would benefit from exploring where individuals search for and locate partners. Although there is a wealth of prior research examining the composition and characteristics of marriage markets, these studies are all grounded in the assumption that individuals do search for partners in the particular market under study—be it a labor market area (South and Lloyd 1992; South, Trent, and Shen 2001), city (Harknett 2008), or college campus (Uecker and Regnerus 2010). However, research is still needed to explore where exactly individuals search for, and locate, partners, as the market most salient for relationship formation may vary for individuals at different stages of the life course.

There are a few limitations to the study worth noting. The study is based on adolescents and young adults in a one geographic area and does not represent the national experience. We hope future studies can assess the influence of sex ratios on young adult relationships in a national context. In addition, we do not consider the effect of quality of partners, and are thus unable to comment on the “marriageability” of the potential mates in our respondents’ markets (Wilson 1996). Our analyses are limited to men and women in emerging adulthood and in some cases the characteristics of a “high quality” dating partner may not be as easily measured as a high quality parent or spouse (Harknett 2008). Third, all couples, especially dating couples, may not have an expectation of monogamy. Although over 85% of TARS respondents reported being in an exclusive relationship, the analyses contain 15% whose relationship may not have been exclusive, and for whom breaking up and dating other partners may not have been uncommon (ancillary analyses controlling for relationship exclusivity produced results similar to those presented). Also, there are several possible methods for measuring sex ratios. Our sex ratio is computed for all individuals ages 16–34, rather than unmarried individuals. However, our operationalization of the “dating market” is consistent with Farber’s (1987) notion that even married individuals are “permanently available” and perpetually on the market for alternatives. Finally, the purpose of our analyses was not to explain racial/ethnic differences in young adult relationship patterns. Our study represents an important first step, but additional studies exploring racial/ethnic differences in the effects of sex ratios on emerging adult relationship behaviors are warranted.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this paper broadens the scope of the influence of demographic context beyond marriage to a consideration of nonmarital relationships. There is relatively little theoretical attention to nonmarital relationship formation and stability among emerging adults. This is an increasingly important omission, as the path to marriage becomes long and winding, often including cohabitation and a series of dating partners; in fact, the early adult years may be characterized as a “relationship-go-round” akin to Cherlin’s (2009) marriage-go-round. Taken together, our results showcase that the sex ratio matters not only for transitions in and out of marriage, but also for the process of searching for and evaluating partners prior to marriage.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD044206), and by the Center for Family and Demographic Research, Bowling Green State University, which has core funding from The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24HD050959-01). Additional support was provided by a grant to Warner and Manning from the National Center for Family and Marriage Research (10450045/58910), which has core funding through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (5 UOI AEOOOOOI-03). The opinions and conclusions expressed herein are solely those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the opinions or policy of any other agency. We thank Raymond Swisher for guidance in constructing the geocoded dataset , Kara Joyner, Kristen Harknett, and Jeremy Uecker for helpful comments on an earlier draft, and extend special thanks to David F. Warner for providing feedback at several points during manuscript development.

Footnotes

Although much of the research on marriage markets focuses on understanding race differences in union formation and fertility (Lichter, LeClere, and McLaughlin 1991; Teachman, Polonko, and Leigh 1987; Lichter et al. 1992), the current investigation does not focus on race differences, due to data limitations. We expand on this in the Measures section and address the implications in the Discussion section.

It may be appropriate to include individuals identifying as bisexual, partly homosexual or 100% homosexual, given that sexual orientation is not a fixed state (particularly at this stage in the life course) (Savin-Williams 2001). However, the marital search and imbalanced sex ratio perspectives address the demographic availability of opposite sex partners, and therefore are, fundamentally, theories of heterosexual relationship behavior. Because we had no a priori reason to expect the availability of opposite sex partners to influence individuals who did not identify as primarily heterosexual, and for consistency with recent research (Harknett 2008; Uecker and Regnerus 2010; Raley and Sullivan 2010) we excluded sexual minorities from the analyses.

It may be more appropriate to refer to this as sexual nonexclusively. Cheating implies behavior by one partner that the other partner is unaware of, and we do not have measures of whether respondents’ partners were aware of their infidelity. However, for the sake of parsimony, we use the term cheating.

There is no firm definition of “emerging adulthood”—Arnett (2004) describes it as beginning roughly around age 18 and involving a variety of transitions (e.g., high school completion, employment, residential mobility). Our analytic sample includes 40 respondents either 17 years-old or still in high school. Excluding these respondents produced results identical to those based on the full sample. Therefore, to maintain the representativeness of the TARS sample, we retain these cases.

References

- Albrecht Carol Mulford, Albrecht Don E. Sex ratio and family structure in the nonmetropolitan United States. Sociological Inquiry. 2001;71:67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Allison Paul D. Missing Data, Sage University Papers Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, 07–136. Thousand Oaks, CA; Sage: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Amato Paul R, Booth Alan. A generation at risk: Growing up in an era of family upheaval. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Amato Paul R, Rogers Stacy J. A longitudinal study of marital problems and subsequent divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1997;59:612–624. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett Jeffrey Jensen. Emerging adulthood: the winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Becker George S. A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Billy John OG, Moore David E. A multilevel analysis of marital and nonmarital fertility in the U.S. Social Forces. 1992;70:977–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell Debra L, Lichter Daniel T. Mate selection among married and cohabiting couples. Journal of Family Issues. 2000;21:275–302. [Google Scholar]

- Blau Francine, Kahn Lawrence, Waldfogel Jane. Understanding young women’s marriage decisions: the role of labor and marriage market conditions. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 2000;53:627–647. [Google Scholar]

- Browning Christopher, Burrington Lori A, Leventhal Tama, Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. Neighborhood Structural Inequality, Collective Efficacy, and Sexual Risk Behavior Among Urban Youth. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49(3):269–285. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin Andrew J. The Marriage-Go-Round: The State of marriage and the family in America today. New York: Alfred A Knopf; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Farber Bernard. The future of the American family: A dialectical account. Journal of Family Issues. 1987;8:431–433. [Google Scholar]

- Felmlee Diane, Sprecher Susan, Bassin Edward. The dissolution of intimate relationships: A hazard model. Social Psychological Quarterly. 1990;53:13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ford Kathleen, Sohn Woosung, Lepkowski James. American adolescents: sexual mixing patterns, bridge partners, and concurrency. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29:13–19. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossett Mark A, Kiecolt K Jill. Mate availability, family formation, and family structure among Black Americans in nonmetropolitan Louisiana 1970–1980. Rural Sociology. 1990;55:305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Fossett Mark A, Kiecolt K Jill. A methodological review of the sex ratio: Alternatives for comparative resarch. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1991;53:941–957. [Google Scholar]

- Fossett Mark A, Jill Kiecolt K. Mate availability and family structure among African Americans in U.S. metropolitan areas. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1993;55:288–302. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano Peggy C, Longmore Monica A, Manning Wendy D. Gender and the meanings of adolescent romantic relationships: A focus on boys. American Sociological Review. 2006;71:260–287. [Google Scholar]

- Guttentag Marcia, Secord Paul F. Too many women? The sex ratio question. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo Karen Benjamin. How do marriage market conditions affect entrance into cohabitation vs. marriage. Social Science Research. 2006;35:332–355. [Google Scholar]

- Harknett Kristen. Mate availability and unmarried parent relationships. Demography. 2008;45(3):555–571. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner Kara, Grace Kao. Interracial relationships and the transition to adulthood. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:563–581. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt K Jill, Fossett Mark A. The effects of mate availability on marriage among Black Americans: A contextual analysis. In: Taylor RJ, Jackson JS, Chatters LM, editors. Family life in Black America. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T, LeClere Felicia B, McLaughlin Diane K. Local marriage markets and the marital behavior of black and white women. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;96:843–867. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T, McLaughlin Diane K, George Kephart, Landry David J. Race and the retreat from marriage: A shortage of marriageable men? American Sociological Review. 1992;57:781–799. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd Kim M, South Scott J. Contextual influences on young men’s transition to first marriage. Social Forces. 1996;74(3):1097–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Longmore Monica A, Manning Wendy D, Giordano Peggy C. Preadolescent parenting strategies and teens’ dating and sexual initiation: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:322–335. [Google Scholar]

- Manning Wendy D, Longmore Monica A, Giordano Peggy C. Adolescents’ involvement in non-romantic sexual activity. Social Science Research. 2005;34:384–407. [Google Scholar]

- Manning Wendy D, Longmore Monica A, Giordano Peggy C. The changing institution of marriage: adolescents’ expectations to cohabit and marry. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:559–575. [Google Scholar]

- Manning Wendy D, Smock Pamela J. First comes cohabitation and then comes marriage? Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23(8):1065–1087. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnish Terra G. Occupation, sex-integration, and divorce. American Economic Review. 2004;94:322–325. [Google Scholar]

- Meier Ann, Hull Kathleen E, Ortyl Timothy A. Young adult relationship values at the intersection of gender and sexuality. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:510–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer Valerie Kincade. A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:563–591. [Google Scholar]

- Raley R Kelly. A shortage of marriageable men? A note on the role of cohabitation in Black-White differences in marriage rates. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:973–983. [Google Scholar]

- Raley R Kelly, Kate Sullivan M. Social-contextual influences on adolescent romantic involvement: The constraints of being a numerical minority. Sociological Spectrum. 2010;30:65–89. doi: 10.1080/02732170903346205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams Ritch. A critique of research on sexual minority youth. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:5–13. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smock Pamela J, Manning Wendy D. Cohabiting partners’ economic circumstances and marriage. Demography. 1997;34:331–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South Scott J, Baumer Eric P. Deciphering community and race effects on adolescent premarital childbearing. Social Forces. 2000;78(4):1379–1408. [Google Scholar]

- South Scott J, Crowder Kyle D. The declining significance of neighborhoods? Marital transitions in the community context. Social Forces. 2000;78(3):1067–1099. [Google Scholar]

- South Scott J, Kim M Lloyd. Marriage opportunities and family formation: Further implications of imbalanced sex ratios. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1992;54:440–451. [Google Scholar]