Short abstract

A 76 year old philanthropist who provides ambulances and welfare centres for Pakistan's poor people now wants to start a non-profit drug company. Abdul Sattar Edhi tells Khabir Ahmad of his plans

Pakistan is a nation where rich people can obtain medical services that are as good as any in the world but where poor people have little access to health care. One man who has tackled this inequity head on is 76 year old Abdul Sattar Edhi, whose charity—the Edhi Welfare Trust—spends around one billion rupees (£10m; $17.5m; €14.5m) a year on projects for people who are destitute, abandoned, or mentally ill.

In a country where all too often government ambulances are used by hospital administrators and their families as private transport, Edhi's fleet of 750 ambulances in more than 100 cities is often the only means of transport for sick, wounded, or dead people. A charge is made for the journeys, but it is a nominal amount. And the charity also runs 300 welfare centres.

Despite the impressive size of his charitable trust today, Edhi comes from a humble background. He grew up in Gujarat state in India and was educated only up to the end of primary school. He and his family migrated from India to Pakistan at the partition in 1947, when Edhi was 19 years old.

He started his trust in 1957 with some volunteers, a result of the influenza epidemic in Karachi that year. “We set up a free medical camp... and appealed for donations. Surprisingly, we had a surplus of 27 000 rupees, which was a lot of money then. So I decided to buy a six foot square shop for a dispensary, and an old van that could be converted into an ambulance. Meanwhile, I started learning to drive,” Edhi recalls.

His late mother was a source of strength and inspiration: “When I was a child, my mother would give me two paise and ask me to spend one myself and the other on poor children in the school. If I spent it all [on] myself, she would become really angry and call me an exploiter.”

It was her protracted illness—paralysis after a stroke and then a mental disorder—that awakened Edhi to the plight of patients in state hospitals. He also discovered that there was a lack of ambulances—only one to serve the whole of Karachi—and of qualified staff in state hospitals. “This is why I have established nursing homes and an ambulance service,” he said.

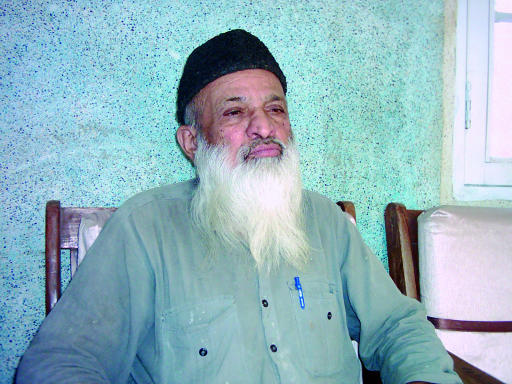

Figure 1.

Abdul Sattar Edhi: “We are increasingly being exploited by multinational pharmaceutical companies”

In 1966 he was criticised by members of a religious party and by local rich people for marrying a nurse who was much younger than him. They tried to pressure him into closing his dispensary. His wife, Bilquise, who now oversees the trust's projects relating to children and women, remembers how stressful things were at the time. “He was threatened. He was under enormous stress. He could not sleep for nights. He would drive almost all night, just around town. He was very depressed,” she says. Her husband laughs when he recalls the predictions people made at the time. “They said I would wind up my projects on the day I marry this young girl,” he says.

In 1998 he faced another crisis. After the murder of Mohammad Saeed, a well known hakeem (traditional healer) in Karachi, which was then engulfed by waves of violence, Edhi was reportedly next on the “hit list.” He contemplated seeking asylum in the United Kingdom but decided against it.

Today he is highly critical of the poor standards of Pakistan's emergency health services. He wants to see a social revolution and a transformation in health care for poor people. Central to that vision is his plan to set up a non-profit pharmaceutical company to produce generic drugs. Much of Pakistan's population does not have access to life saving drugs because they are too expensive. “We are increasingly being exploited by multinational pharmaceutical companies. Why not make generic drugs ourselves?” he asks.

Edhi is now an old man, but he has a youthful outlook. He is happy to talk about his desire to marry more than one woman, and about his love life, normally a taboo subject in Pakistan. Despite the criticism of his marriage to Bilquise, his years as a married man have been marked by activity and productivity. He plans to buy another 300 more ambulances by June 2004.

Shehzad Roy, one of Pakistan's most popular singers, believes that Edhi's work is of huge importance to the country. “He is simply Pakistan's greatest asset, and an angel of mercy,” he says. Roy, who runs a charitable trust of his own that has just launched an initiative to provide education and health care services for underprivileged children, describes him as his inspiration. “He works day and night and does not care what clothing he wears or what kind of food he eats.”

Edhi cannot stand hypocrisy, and he reserves a particular hatred for “Pakistan's lying politicians and exploiting capitalists,” who he believes are particularly responsible for the miseries of the poor. “They are dead against me. It is mostly the middle class that gives us donations,” he said.

Edhi also condemns Pakistan and India's increasing spending on nuclear weapon and other military programmes and says they have only worsened the lives of poor people in both countries. He has continually called for friendship between the two countries and for removal of visa requirements for travelling between them. Such opinions have made him the target of state sponsored character assassination campaigns, he says. “I have been called a traitor and an Indian agent by government ministers for many years. But that mood has changed dramatically in recent months, as both countries have begun to move relations forward.”

Despite his achievements and fame Edhi is still not without his critics, particularly over his views on contentious issues such as adoption of unwanted children. Cradles have been installed at his centres where unwanted children can be left safely. Edhi says that many women have nowhere to turn and that all they can do is get rid of the baby. “If I don't provide this service, I fear many mothers would suffocate their unwanted babies to death in plastic bags and dump them in trash bins.” Particularly worrying is that 95% of the children left in cradles are girls.