Abstract

Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, this paper examines individual and neighborhood predictors of adolescent and young adult survival expectations — their confidence of surviving to age 35. Analyses revealed that within-person increases in depression and violent perpetration decreased the odds of expecting to survive. Individuals who rated themselves in good health and received routine physical care had greater survival expectations. Consistent with documented health disparities, Black and Hispanic youth had lower survival expectations than did their White peers. Neighborhood poverty was linked to diminished survival expectations both within and between persons, with the between person association remaining significant controlling for mental and physical health, exposure to violence, own violence, and a wide range of socio-demographic factors.

Recent research within public health and criminology has found that anticipation of an early death is associated with a wide range of risk-taking behaviors, including fighting, weapon use, delinquency, unsafe sexual behavior, HIV and AIDS transmission, and suicide attempts (Borowsky, Ireland, & Resnick, 2009; Brezina, Tekin, & Topalli, 2009). Not yet well demonstrated, particularly within a nationally representative sample, is how youths’ “survival expectations”—their certainty that they will survive to various ages—are embedded within social structural contexts, particularly neighborhoods. That is, research has not yet explored whether these expectations are largely a function of individual characteristics — a component of individuals’ attitudes and behaviors (e.g., violence)—or whether their foundations also lie outside the individual, attributable to membership in a given raical and ethnic or socioeconomic group, or to the structural conditions and risks in one’s neighborhood environment.

Health risks exist across the various contexts in which adolescent development is embedded. Given youths’ limited geographic mobility, neighborhoods are an important life course context of health and development. Survival expectations may be undermined by stressors associated with neighborhood poverty and exposure to community violence (Foster, Hagan, & Brooks-Gunn, 2008). The pervasive consequences of neighborhood disadvantage are vividly depicted in Alex Kotzlowitz’s (1991) classic There are No Children Here, a study of the challenges faced by two brothers growing up in a Chicago public housing project, in a poor and violent neighborhood. These challenges are captured by one of the brothers’ responses to the question of what he wanted to be – “If I grow up, I’d like to be a bus driver” (Kotlowitz, 1991, p. x, emphasis added). As Young powerfully argues, a constant threat of violence undermines “the essential prerequisite for conceiving of future life chances: a consistently secure belief that [one] could survive into adulthood” (Young, 1999, p. 210). Living in a disadvantaged neighborhood may erode optimism and foster hopelessness and negativity (Cutrona, Wallace, & Wesner, 2006).

The present study extends research on adolescent survival expectations by examining the possible origins of adolescents’ beliefs about their futures, and modeling trajectories of survival expectations into young adulthood. Using data from three waves of the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health) and two-level hierarchical generalized linear modeling (HGLM), we examine individual and social structural factors (e.g., social group memberships, neighborhood poverty) that may affect adolescents’ survival expectations.

Background

Perceived Life Chances in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood

Adolescence is an important developmental period, marked by several social and biological transitions. Behavior patterns established during adolescence are important for initiating trajectories of health and well-being in adulthood. This period involves numerous choices (Furstenberg, 2000) that set the stage for adulthood (Crosnoe, 2009; Harris, Duncan, & Boisjoly, 2002). It is during adolescence that several key developmental tasks are accomplished, including becoming physically and sexually mature, acquiring the skills necessary for establishing and fulfilling adult roles, and gaining autonomy from parents (Elliott & Feldman, 1990). Goals, abilities, and values are shaped through the socialization process, and modified by the opportunities and obstacles individuals face (Clausen, 1991). Thinking about the future, and mapping out a coherent plan for ones’ life are key developmental tasks during adolescence, and are important factors as youth approach the transition to adulthood (Crockett & Bingham, 2000; Greene, 1990; Young, 1999).

Just as adolescence is a key developmental period marked by numerous transitions, the transition to adulthood is marked by multiple and often linked transitions, such as high school completion and pursuit of higher education, leaving the parental home, entry into the workforce, and family formation (Settersten, Furstenberg, & Rumbaut, 2005; Shanahan, 2000). Scholars note that this transition has become increasingly individualized, heterogeneous, and protracted (Fussell & Furstenberg, 2005; Settersten et al., 2005; Shanahan, 2000), so much so that Arnett (2004) has described it as a unique stage, one of “emerging adulthood.” Thus the increasing uncertainty experienced during the transition to adulthood likely makes planning and expectations about the future all the more important for individuals’ well-being.

Adolescent and Young Adult Survival Expectations

Survival expectations are closely related to the concept of subjective life expectancy—individuals’ estimates of the ages to which they will survive, or a more general sense of one’s chances of surviving into the future. The concept of survival expectations has been referred to as future time perspective (Borowsky et al., 2009), future certainty (Caldwell, Wiebe, & Cleveland, 2006), and anticipation of early death (Borowsky et al., 2009; Fischhoff, de Bruin, Parker, Millstein, & Halpern-Felsher, 2010). Brezina and colleagues (2009) describe anticipating an early death as having a sense of “futurelessness.” Their qualitative interviews showed that expectation of early death among adolescents fostered feelings of powerlessness, worthlessness, and having nothing to lose. This is consistent with Harris and colleagues’ (2002) interpretation of diminished future expectations as “nothing to lose” attitudes.

Contrary to the stereotype of perceived invincibility, adolescents tend to overestimate their risk of dying, in contrast to adults, whose perceived survival expectations tend to be more accurate (Borowsky et al., 2009; Fischhoff et al., 2010). For example, Fischhoff and colleagues’ (2000) found that, on average, teenage respondents estimated an 18.6% chance of dying from any cause in the next year—substantially higher than their statistical mortality rate of 0.08%. Likewise, Jamieson and Romer (2008) found that 6.7% of 14 to 22 year olds in a nationally representative survey agreed they would not live past age 30.

Several recent studies have linked adolescent survival expectations to a range of risky behaviors. Having doubts about one’s survival into adulthood may lead adolescents to feel hopeless, and that not much is at stake, therefore making them more likely to engage in risky behaviors (Borowsky et al., 2009; Jamieson & Romer, 2008). For example, in Borowsky and colleagues’ (2009) analysis, perceived early mortality was positively associated with attempted suicide, fight-related injury, criminal justice system involvement, unsafe sexual activity, and contracting HIV. Brezina and colleagues’ (Brezina et al., 2009) found anticipation of an early death predicted a variety of offending behaviors, from minor delinquency, to more serious delinquency and violence.

The Sources of Adolescent Survival Expectations

Not well understood are where survival expectations come from, a key limitation given the many potential negative consequences of having low expectations of surviving. Recognizing this current gap, the goal of the present study is to examine individual, social structural, and contextual predictors of survival expectations in adolescence and young adulthood. We consider individual factors such as low self-control and own violent behavior, self-assessments of risks and physical and psychological well-being, racial, ethnic, and SES differences in life expectancy, as well as characteristics neighborhood contexts.

Evaluations of Physical Health and Psychological Well-Being

Research on adults indicates that subjective life expectancy reflects, in part, appraisals of current physical and psychological well-being. For example, Ross, and Mirowsky (2002) found that adults who considered themselves in good health reported expecting to live longer than those reporting poor health. Perceived health was significantly associated with subjective life expectancy, but chronic conditions and physical limitations were not. Individuals modified their subjective life expectancies based on new information about their health such as the onset of disease (Hurd & McGarry, 2002).

Research suggests that youth in disadvantaged neighborhoods may be at a particular risk of perceiving that their health is deteriorating. Geronimus (Geronimus, 1992, 1996) advanced the concept of “weathering,” arguing that chronic stressors associated with poverty and racial discrimination produce a cumulative “wear and tear” on the body that leads to premature physical decline—particularly for women. Whereas middle-class women might begin to experience physical decline in their 40’s or even much later, poor Black women begin to experience such symptoms as early as their 20’s and thus perceive themselves as having an accelerated life span. Foster, Hagan, and Brooks-Gunn (2008) recently proposed a social psychological corollary to weathering called “subjective weathering.” In addition to perceptions of physical deterioration, their conceptualization of subjective weathering captures the perception that one has grown up faster than others as a result of taking on adult responsibilities and concerns at an early age (see also Burton, 2002). Johnson and Mollborn (2009) similarly found experiences of economic hardship in childhood and adolescence to be associated with feeling older during emerging adulthood (see also Mello & Swanson, 2007).

Disadvantaged neighborhood contexts and deteriorating physical health are also often associated with diminished psychological well-being (Aneshensel & Sucoff, 1996; Yen & Kaplan, 1999; Mair, Diez Roux, & Galea, 2008). Thus, this study incorporates measures of both perceived overall health and depression as predictors of perceived survival expectations.

Group-Based Mortality Differences

In addition to perceptions of current health, survival expectations may also reflect anticipated future health associated with social group differences in life expectancy. Numerous studies have documented racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in health and life expectancy. Racial and ethnic minorities and lower SES individuals have worse health and shorter life expectancies (Kronenfeld, 2009). Geronimus and colleagues (2001) calculated population-level mortality estimates for Black and White adults. At age 16, life expectancy among White women is 64, among Black women is 60, among White men is 58 and among Black men is 52. In a study of deaths over a 3-year period in California, Clarke and colleagues (2010) similarly observed race and class disparities in life expectancy. They calculated an almost 20 year gap in life expectancy between the socio-demographic group with the highest life expectancy (high SES Asian females) and the group with the lowest life expectancy (low SES Black males). Interestingly, research on older adults by Bulanda and Zhang (2009) found that Blacks’ subjective life expectancy was higher than Whites’, despite a lower actual life expectancy.

While much of the research on morbidity and mortality inequalities focuses on adults, a recent report by Flores (2010) highlights that these disparities also extend to children and adolescents. Racial and ethnic disparities exist across a spectrum of health indicators, including infant and child mortality, access to and use of health care and health insurance, low birth weight, and chronic diseases such as asthma and obesity. Low SES youth are also more likely to engage in risky health behaviors, and have higher rates of injury and chronic health problems—all of which may combine to impact their future health trajectories (Kronenfeld, 2009).

Racial and ethnic disparities are also observed in the teen death rate. Non-Hispanic Black teenagers have a death rate of 64.5 deaths per 100,000 population compared to 47.1 for Hispanics and 47.0 for non-Hispanic White teens (Minino, 2010). The disparities are even more pronounced among males. The death rate for Black male teenagers is 94.1 compared to 68 for Hispanic males and 62 for non-Hispanic Whites. This discrepancy exists because Black male teenagers are disproportionately affected by homicide—the leading cause of death for Black male teens. Black male teenagers’ risk of death by homicide (39.2 per 100,000) is twice the risk for Hispanic males (17.1 per 100,000) and 15 times the risk for White males (2.6 per 100,000).

Class differences do not simply reflect racial and ethnic differences—class-based health disparities can be seen across all racial and ethnic groups (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2008). Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic differences in survival expectations may lead to differences in risk behaviors that undermine health and well-being, further exacerbating health disparities among vulnerable populations. Research focusing on health inequalities has reported strong associations between subjective life expectancy and various forms of socioeconomic status, most notably education, and the severity and recency of economic hardship (Mirowsky & Ross, 2000; Ross & Mirowsky, 2002).

Neighborhood Disadvantage

A person’s health, likelihood of becoming sick, and risk of dying prematurely are influenced by social contextual factors, including the quality of one’s neighborhood (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2008). William J. Wilson (W. J. Wilson, 1987, 1996) focused social science attention on the role of concentrated poverty and unemployment within neighborhoods in undermining the life chances of disadvantaged youth. Following Wilson, researchers have observed significant associations between neighborhood poverty and a wide range of outcomes across the life course such as delinquency, violence, depression, substance use, obesity, sexual risk-taking, infectious diseases, teenage child-bearing, and high school dropout (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002).

Although crime and violence have typically been treated as outcomes associated with neighborhood poverty, researchers are increasingly recognizing that crime and violence have consequences of their own for neighborhood residents. Arguing that discounting one’s future may reflect the appropriate weighting of one’s current circumstances, Wilson and Daly (1997) assessed the association between neighborhood homicide rates and life expectancy in Chicago. Findings revealed that 1988–1993 neighborhood-specific life expectancy and homicide rates were highly and negatively correlated for both males and females. Although Wilson and Daly (1997) computed actual life expectancies rather than surveying residents on their subjective expectancies, examination of birth rates suggested that residents behaved as if they had adjusted their perceptions of life expectancy with respect to their current environment—that is, women gave birth much earlier in neighborhoods with higher crime and lower life expectancies.

Situational and Behavioral Characteristics

Exposure to violence is an important mechanism through which neighborhoods may influence well-being, particularly for youth (Harding, 2009). The National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence found that a full 60 percent of youth in the United States had been exposed to some form of violence in the past year. Included within this figure are 36.7 percent of children who had been assaulted without injury, 14.9 percent assaulted with a weapon or with injury, and 19.2 percent who had witnessed community violence (Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, Hamby, & Kracke, 2009). Many studies show that residents in disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to witness and experience violence than are their counterparts in more advantaged neighborhoods (e.g., Aisenberg & Herrenkohl, 2008; Bursik & Grasmick, 1993; Gibson, Morris, & Beaver, 2009).

Exposure to community violence has been linked to a host of negative short-term outcomes, including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicidal behaviors, and aggression (Margolin & Gordis, 2000; Sampson et al., 2002; Scarpa, 2001). Aneshensel and Sucoff (1996) found that youth exposed to neighborhood hazards such as crime, violence, drug use, and graffiti, were more likely to perceive their neighborhoods as dangerous, report mental health problems, and engage in problem behavior. Individuals in disadvantaged areas who come to view their neighborhoods as threatening and unsafe are at risk for internalizing feelings of marginalization, powerlessness, and despair (Aisenberg & Herrenkohl, 2008). Exposure to violence has also been linked to youths’ aggressive behaviors, beliefs supporting aggression, (McMahon, Felix, Halpert, & Petropoulos, 2009; Parente & Mahoney, 2009), and young adult criminal offending (Eitle & Turner, 2002).

As Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) assert, low self-control is an additional potential cause of deviant or problem behavior. Persons with low self-control are described as impulsive, sensation-seeking, and predisposed to risk-taking behaviors, and as such may be more likely to place themselves in risky situations that may diminish their survival expectations. Calling into question the view that low self-control is solely an individual characteristic, however, recent studies have shown low self-control to be associated with neighborhood disadvantage and exposure to hazardous community conditions (Bellair & McNulty, 2005; Pratt, Turner, & Piquero, 2004; Teasdale & Silver, 2009). Thus for adolescents, witnessing or being a victim of violence, along with fearing for one’s safety, or engaging in risky, impulsive, or violent behaviors all raise the possibility that the end of one’s life may be relatively near (Johnson & Mollborn, 2009; Kotlowitz, 1991).

Stability and Change in the Transition to Adulthood

A topic of increasing interest is how neighborhood experiences change over the life course, whether due to residential moves or to changes in the neighborhoods themselves. For some disadvantaged families, neighborhood poverty is a life-long, durable form of inequality; a trap from which residential mobility is difficult, and which is often replicated in the next generation (Quillian, 2003; Sampson & Morenoff, 2006; Sampson & Sharkey, 2008; Sharkey, 2008; Timberlake, 2007). The transition to adulthood is a particularly important stage at which changes in neighborhood environments often occur, as many youth move out of parental homes to pursue college, take a job, start their own family, etc.

Thus, the present study examines how neighborhood and other factors relate to trajectories of survival expectations over time using multiple waves of data at both the individual and neighborhood levels. Our multilevel models, described in more technical detail below, are able to model changes in survival expectations as a function of both between-person and within-person changes in neighborhood characteristics, and other time-varying factors. Between-person differences in survival expectations can then be related to mean differences between persons (e.g., respondents consistently living in disadvantaged neighborhoods throughout the study period versus those in consistently advantaged circumstances), whereas within-person changes in survival expectations can be related to time-varying characteristics (e.g., respondents experiencing a change in neighborhood disadvantage or exposure to violence between adolescence and early adulthood).

The Current Study

To recap, the purpose of this study is to more fully examine the individual, social structural, and contextual correlates of survival expectations in adolescence and young adulthood. We focus in particular on how these expectations are embedded within the context of disadvantaged neighborhoods and how survival expectations may change as adolescents move into young adulthood. Previous research on survival expectations has observed associations between these attitudes and family socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, and other individual-level characteristics, and also linked diminished expectations to risky and deviant behaviors (Borowsky et al., 2009; Foster et al., 2008; Johnson & Mollborn, 2009), but researchers have not made linkages to neighborhood context. We expect that living in a poor neighborhood in adolescence or young adulthood will be associated with diminished survival expectations, and that this association will persist above and beyond individual characteristics, self-rated health, and demographically-based group differences in mortality. We also expect that exposure to violence will be a particularly important component of neighborhood context that will be associated with lower survival expectations net of individual characteristics.

Method

Data and Sample

Data were drawn from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), a nationally representative sample of adolescents in schools, grades 7 through 12, in 1995 (Bearman, Jones, & Udry, 1997). The primary sampling frame included 80 representative high schools, and their “feeder” middle schools, stratified by region of country, degree of urbanicity, school type (i.e., public and private), racial and ethnic composition, and school size. Each participating school provided a roster of all enrolled students, from which a core sample of 20,745 adolescents was randomly selected for in-home interviews. One year later (1996), respondents originally in the 7th–11th grades (88% of the core sample) were surveyed again for the Wave II interview (n=14,738). Approximately six years after the Wave II interview (2001–2002), all Wave I participants who could be located were re-interviewed for a third wave, with a response rate of about 80% (n=15,197, respondents were ages 18–28).

Our analyses used data from Waves I, II, and III of the Add Health in-home interviews, along with data from the Waves I, II, and III Contextual Databases. An advantage of the growth curve analyses (described below) is that the analytic sample need not be limited to respondents who participated at all three waves (respondents participating at Wave I only contribute to the intercept, but not the slope of the growth curve analyses). Although multilevel modeling is able to use any available data at level one (within person), data at level two (between persons) must be complete. Therefore, among the 20,745 original Wave I respondents, missing data were multiply imputed using Stata’s ice procedure to create 10 imputed datasets. Although we used core demographics (race and ethnicity, nativity, gender, family structure, and age) in the multiple imputation models, we did not impute missing demographic data; rather, we excluded respondents missing data on core demographics (n = 44) after the imputation was completed. Our analyses also excluded 598 respondents whose addresses were not geocoded at any given wave, and, to ensure adequate cell sizes across each age, we also excluded observations for respondents at the youngest age at Wave I (age 11) and the oldest age at Wave III (26, 27, and 28)—this amounted to an additional exclusion of 132 observations. In total, these exclusions resulted in a final analytic sample size of 20,103 adolescents, contributing 48,864 observations. These respondents were distributed across 2,431 census tracts at Wave I (average of 8.27 respondents/tract), 2,080 tracts at Wave II (9.66 respondents/tract), and 5,859 tracts at Wave III (3.43 respondents/tract).

Measures

Dependent Variable

Survival Expectations

Respondents were asked a series of questions about the likelihood that various events would occur to them during their adolescence and the transition to early adulthood. Survival expectations was measured at all three waves via respondents’ assessment of the likelihood that they will “survive to age 35.” Original response options were: (a) almost no chance; (b) some chance, but probably not; (c) a 50-50 chance; (d) a good chance, and; (e) almost certain. Due to small cell sizes for the lower chances of surviving categories, response options were dichotomized into 1 = a good chance or almost certain and 0 = all other categories. This approach of dichotomizing is consistent with previous research using this variable (e.g., Borowsky et al., 2009). Thus analyses here model the odds of expecting at least a good chance of surviving to age 35.

Independent Variables

Mental and Physical Health

We use four time-varying measures of perceived current mental and physical health status and demands. Depression, was measured via the mean of ten items adapted from the CES-D; examples include questions about the frequency during the past week that respondents felt they could not shake the blues, were bothered by things, felt sad, felt too tired to do things, and felt that people disliked them (Cronbach’s α = 0.80, 0.81, 0.81 at Waves I–III, respectively). Self-rated health was measured by responses to the question: “In general, how is your health?” Original response options (ranging from 0 = excellent to 4 = poor) were reverse-coded so that higher scores corresponded to better health. This measure has been found to be a reliable indicator of overall health, and in some cases is more predictive of future health outcomes than physician reports (Idler & Benyamini, 1997). Unmet medical need, was measured via the question: “Has there been any time in the past year that you thought you should get medical care but did not?” (0 = no, 1 = yes). Finally, routine medical care, assessed whether respondents had received a medical examination during the past year (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Demographic Characteristics

As discussed above, much research has documented racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic group-based disparities in health and well-being. To explore whether these disparities extend to adolescent and young adult survival expectations, we included time-invariant measures of race and ethnicity and social class. Family socioeconomic status was a combination of parent’s education and parent’s occupational level, using a commonly employed scale (Ford, Bearman, & Moody, 1999). Parent’s education was measured by parent reports of how far they went in school, with categories from “never went to school” to “professional training beyond a four-year college” converted into years of schooling completed. Parent’s occupational level was a multi-category variable of parent’s type of employment, collapsed into categories that include professional, managerial or technical, and service. Family structure was measured via three dummy variables for youth living with two unmarried parents, a single parent, or all other family structures (0 = no, 1 = yes); two biological married parents served as the reference category. Race, ethnicity, and nativity were measured with mutually exclusive dummy variables for Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Black, Asian, and Other races (non-Hispanic White was the reference category), and a dummy variable indicating immigrant status (0 = U.S. native, 1 = foreign born). We controlled for respondents’ gender with a dummy variable for female and respondents’ residential stability with a measure of years lived in the neighborhood at Wave I (because this measure was collinear with age in the multivariate analyses, we collapsed it into quartiles). Finally, we included respondents’ age at baseline (Wave I) to account for differences in survival expectations that may be due to the age heterogeneity of the sample (i.e., respondents at Wave I ranged from ages 11 through 21; respondents first interviewed at older ages may be more inclined to expect to survive to age 35 simply because they are closer to that age than younger interviewees).

Neighborhood Characteristics

Neighborhoods were defined as respondents’ census tract of residence at each wave. Respondents’ addresses were confidentially linked by the Add Health project—to 1990 Census data for Waves I and II (Billy, Wenzlow, & Grady, 1998), and 2000 Census data for Wave III (Swisher, 2003)—and used to assess neighborhood socioeconomic and demographic structure. Though tracts do not necessarily reflect residents’ definitions of their neighborhoods, they are generally considered to be the most feasible approach in national studies, and facilitate comparisons to prior studies (Sampson et al., 2002). Consistent with a life course perspective, early life neighborhood context has long-term consequences for development, but youth may not stay in the same neighborhood during their entire adolescence; thus, we treated neighborhood characteristics as time-varying, allowing them to change if adolescents changed neighborhoods, or neighborhoods changed around them. Neighborhood disadvantage was a time-varying indicator, measured as a mean scale comprised of the tract-level (a) proportion of female-headed households, (b) proportion of families earning less than $15,000, (c) proportion of residents living below the federal poverty level, (d) the proportion of residents age 25 and older with less than a high school education, (e) the proportion of households receiving public assistance, and (f) the male unemployment rate (Cronbach’s α = 0.94, 0.94, 0.89 at Waves I–III, respectively). The original measure ranged from 0.00 – 1.00; however, we multiplied this measure by 10 to facilitate interpretation, such that a 1-unit increase corresponded to a 10% increase in neighborhood disadvantage. Urbanicity (time-varying) was measured as the proportion of residents residing in urban areas at each of the three waves; although this measure ranged from 0.00 – 1.00, 49.24% of respondents resided in a neighborhood where the proportion of urban residents was 1.00, and 20.95% resided in a neighborhood where the proportion of urban residents was 0.00. Residential stability (time-varying) was measured as the proportion of residents living in the same home as five years prior.

Situational and Behavioral Characteristics

A time-varying indicator of exposure to violence was measured by items asking about the frequency within the last year that adolescents: (a) saw someone shot or stabbed; (b) had a knife or gun pulled on them; (c) were jumped (at Wave III this was assessed via two questions—frequency respondents were beaten up and something was stolen from them and the frequency respondents were beaten up but nothing was stolen from them); (d) were cut or stabbed; and (e) were shot. Although we discuss exposure to violence as a correlate of disadvantaged neighborhoods, we acknowledge that we cannot know for certain whether this exposure occurred within respondents’ neighborhoods. Responses ranged from 0 = never to 2 = more than once, but due to the infrequency of these events, exposure to violence was measured at each wave by a dichotomous indicator coded 1 for experiencing any of these five incidents, and 0 if never experiencing these incidents. This combination of witnessed and directly experienced violence is consistent with research into the effects of violence on mental health (Osofsky, 1995).

To account for the fact that aggressive adolescents may select themselves into violent situations, models also included time-varying measures of impulsivity/low self-control and adolescent self-reports of their own violence. As a proxy for impulsivity/low self-control, we included the time-varying item “when making decisions, you usually go with your gut feeling” (response options ranging from 1=strongly agree to 5=strongly disagree were reverse-coded so that higher scores correspond to more impulsive tendencies). Violent behavior was gauged at each wave from adolescent self-reports of any involvement, over the past 12 months, in the following: (a) hurt someone badly enough in a physical fight that he/she needed care from a doctor or nurse; (b) used/threatened to use a weapon to get something from someone; (c) taken part in a group fight; (d) you pulled a knife or gun on someone; (e) you shot or stabbed someone; (f) you carried a weapon to school/work; and (g) you used a weapon in a fight. Original options (0 = never, 1 = 1 or 2 times, 2 = 3 or 4 times, 3 = 5 or more times) were first dichotomized (0 = never, 1 = 1 or more times), and the seven items were then summed, resulting in a measure ranging from 0–7 at each wave.

Analytic Strategy

To assess the individual and neighborhood correlates of survival expectations, we used a 2-level hierarchical generalized linear model (HGLM) for binary outcomes with a logit link; analyses were conducted with HLM 6.08 (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). The HGLM approach allowed us to model trajectories of survival expectations over time, while incorporating observations missing at random. We restructured the data into a cohort sequential design (also known as an accelerated cohort design) which uses adolescent age (centered at age 12) rather than wave as the metric of time; this allowed us to model trajectories of survival expectations from the youngest observed age (age 12) through the oldest age (age 25) (Ennett et al., 2006). Pooling across the three waves of Add Health data, there were 48,864 observations nested within the analytic sample of 20,103 adolescents.

In preliminary analyses we estimated a 3-level HGLM model that accounted for clustering of respondents in neighborhoods at Wave I in the level-3 equation. The results were consistent with those obtained in the 2-level model; however, since we are unable to follow the same neighborhoods longitudinally, and because respondents were residentially mobile across waves, we utilize the 2-level model and focus on the effects of changing neighborhood characteristics with age. Although our outcome is binary, we estimated an unconditional means model, specifying the outcome as continuous, in order to obtain approximations of the variance at each level. Results indicate that the variance can be partitioned as follows: 77.4% at level one (within-person), 18.9% at level two (between-person), and 3.7% at level three (between neighborhoods). Given the small amount of variance at level three, relative to levels one and two, we believe any bias to our findings resulting from not modeling level three variance is likely minimal.

The final model involves observations nested within adolescents. The level-1 equation, which captures within-person variation, is given by:

| (Eq. 1) |

which models nti, the log odds of expecting at least a good chance of surviving to 35 at age t for person i as a function of an initial level of survival expectations (π0i), change in that level with age, and a vector of time-varying covariates (Xti). Consistent with the approach suggested by Horney and colleagues (Horney, Osgood, & Marshall, 1995; see also Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002; Singer & Willett, 2003), the values for time-varying Xti in the level-one equation were transformed into deviations from each individual’s mean calculated across all periods of observation (that is, they were group-mean centered for each individual, reflecting the extent of change, relative to one’s mean over time). These individual means (X̅i) were then included as explanatory variables in the level-2 equation, which captures between-person variation in survival expectations:

| (Eq. 2) |

| (Eq. 3) |

| (Eq. 4) |

| (Eq. 5) |

Here, the effects of between-person differences in average mental and physical health, neighborhood characteristics, and behavioral or situational characteristics on the intercept (initial value) and slope (change with age) of survival expectations were captured by β01, β11, and β21 (Equations 2–4). That is, these measures were modeled as predictors of both the intercept and slope of survival expectations. Within-person change is captured by β30 (Equation 5). Using person-centered indicators in the level-one equation restricts β30 to within-person change—not computing these deviation scores would result in an indicator capturing combined effects of between-person differences and within-person change (Horney et al., 1995).

Consistent with South and Crowder (1999), we used robust standard errors to account for the slight clustering of respondents within neighborhoods. All analyses (descriptive and multivariate) were unweighted. Winship and Radbill (1994) note that when the weights are a function of the independent variables—as is largely the case for the grand sampling weights in Add Health, which are adjusted for age, gender, race and ethnicity, and sibling status—unweighted regression is preferred, and is less likely to produce biased estimates. A sample in which racial and ethnic minorities are oversampled (as was the case in Add Health) is more efficient for drawing conclusions about racial and ethnic differences when it is unweighted, than is a representative (that is, weighted) sample. Because individuals’ race and ethnicity were key focal independent variables in our analyses, our analyses were unweighted in order to enable us to utilize fully the racial and ethnic oversamples in Add Health. Further, there were 1,764 respondents (8.7% of the analytic sample) missing sample weights, and this missingness was significantly correlated with our dependent variable, as well as most of our focal independent variables. Therefore, excluding respondents lacking valid sample weights (which would be necessary to utilize these weights) would risk biasing our results.

We first estimated an unconditional growth model to determine the shape of growth in survival expectations from age 12 to age 25, assessing whether the shape was best captured by linear (age) or curvilinear (age2) growth. In this unconditional model, the linear predictor of adolescents’ log odds of expecting to survive to 35 was a function of initial survival expectations (the intercept), and rate of change (the slope). Results indicated that the shape of growth was best represented with a quadratic age term, capturing the curvilinear shape. Thus all models included age (centered at age 12) and age2 (based on the centered age measure).

Results

Sample Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive characteristics of the dependent and independent variables across all three waves of data. The sample was fairly evenly split by gender (51% female), and just over half of respondents were White. Respondents were, on average, 15.7 years old at Wave I, 16 at Wave II, and 22 at Wave III. At Wave I, just over a quarter of respondents (26.4%) reported some exposure to violence; this declined to less than 10% of respondents at Wave III. Violent perpetration was also considerably low at each time point. Respondents rated themselves as fairly healthy, with many reporting receiving routine physical care and less than one-fifth reporting unmet medical needs at any wave. Respondents resided in neighborhoods where the average neighborhood disadvantage was fairly low, particularly at Wave III. At Waves I and II, approximately 85% and 84% of respondents perceived a good chance or were almost certain that they would survive to age 35—this increased to 92% of respondents at Wave III.

TABLE 1.

| Wave I | Wave II | Wave III | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Range | Mean | SE | Range | Mean | SE | Range | |

| Expect to survive to age 35 | 0.850 | 0.003 | 0.839 | 0.003 | 0.923 | 0.002 | |||

| Mental and Physical Health | |||||||||

| Depression | 0.663 | 0.003 | 0–3 | 0.656 | 0.003 | 0–3 | 0.517 | 0.003 | 0–3 |

| Self-rated physical health | 2.879 | 0.006 | 0–4 | 2.913 | 0.007 | 0–4 | 3.013 | 0.007 | 0–4 |

| Routine physical care | 0.644 | 0.003 | 0.631 | 0.003 | 0.347 | 0.004 | |||

| Unmet medical needs | 0.202 | 0.003 | 0.208 | 0.003 | 0.234 | 0.003 | |||

| Behavioral Characteristics | |||||||||

| Impulsivity | 2.003 | 0.008 | 0–4 | 1.977 | 0.009 | 0–4 | 2.199 | 0.009 | 0–4 |

| Exposure to violence | 0.264 | 0.003 | 0.191 | 0.003 | 0.091 | 0.003 | |||

| Violent perpetration | 0.6598 | 0.008 | 0–7 | 0.461 | 0.008 | 0–7 | 0.211 | 0.008 | 0–7 |

| Neighborhood Characteristics | |||||||||

| Neighborhood disadvantage | 1.661 | 0.007 | 0.00–8.74 | 1.650 | 0.008 | 0.20–8.74 | 1.428 | 0.007 | 0.03–6.13 |

| Proportion residing in urban area | 0.629 | 0.003 | 0.00–1.00 | 0.618 | 0.004 | 0.00–1.00 | 0.738 | 0.003 | 0.00–1.00 |

| Proportion residents in same house 5 years prior | 0.552 | 0.001 | 0.03–0.87 | 0.553 | 0.001 | 0.03–0.87 | 0.523 | 0.001 | 0.00–0.85 |

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Age | 15.701 | 0.012 | 12–21 | 16.218 | 0.014 | 12–22 | 22.005 | 0.015 | 17–25 |

| Female | 0.506 | ||||||||

| Race, ethnicity, and nativity | |||||||||

| White | 0.523 | ||||||||

| Black | 0.218 | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.172 | ||||||||

| Asian | 0.068 | ||||||||

| American Indian/Other race | 0.019 | ||||||||

| Foreign born | 0.093 | ||||||||

| Family structure | |||||||||

| Two biological married parents | 0.500 | ||||||||

| Two parents, unmarried | 0.157 | ||||||||

| Single parent | 0.275 | ||||||||

| Other family structure | 0.068 | ||||||||

| Family SES | 4.542 | 0.0197 | 0–9 | ||||||

| Years in neighborhood (in quartiles) | 1.660 | 0.008 | 0–3 | ||||||

Notes: n = 48,864 observations, 20,103 respondents.

Missing data multiply imputed via the Stata ice procedure

Ranges not shown for dichotomously coded variables

Predictors of Adolescent and Young Adult Survival Expectations

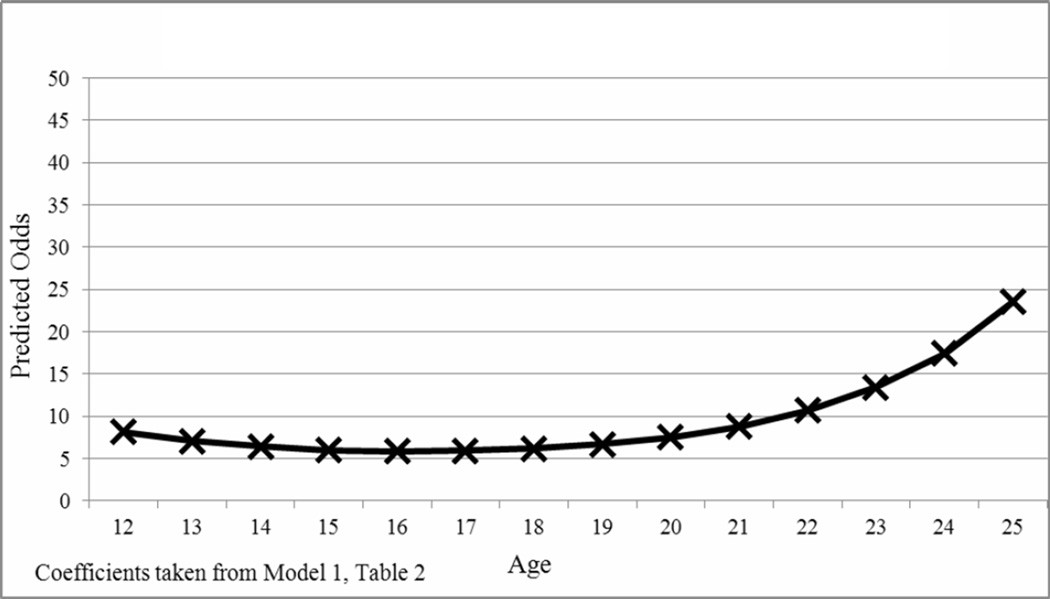

Model 1 in Table 2 presents the results of the unconditional growth curve model exploring the shape of growth in survival expectations between ages 12 to 25. Recall that the dependent variable was dichotomized, such that a value of 1 represents respondents perceiving that they have a good chance or are almost certain they will survive to age 35. For parsimony, we discuss this as the odds of expecting to survive. The results of Model 1 are displayed in the Figure, which shows that the predicted odds of expecting to survive to age 35 were fairly stable between ages 12 and 20, and then increase dramatically after age 20. This seems reasonable, as surviving to 35 should seem increasingly tenable as adolescents actually approach that age.

TABLE 2.

HIERARCHICAL GENERALIZED LINEAR GROWTH MODELS OF ADOLESCENT SURVIVAL EXPECTATIONS

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | b | b | b | b | b | |

| Intercept | 2.095*** | 2.275*** | 2.190*** | 3.222*** | 2.046*** | 2.201*** |

| Linear growth (age) | −0.155*** | −0.201*** | −0.091*** | −0.244*** | −0.147*** | −0.128** |

| Quadratic growth (age2) | 0.018*** | 0.022*** | 0.014*** | 0.025*** | 0.017*** | 0.018*** |

| Level-1 within-person (time-varying) covariatesa | ||||||

| Mental and Physical Health | ||||||

| Depression | −0.554*** | −0.560*** | ||||

| Self-rated physical health | 0.135*** | 0.133*** | ||||

| Routine physical care | 0.048 | 0.079* | ||||

| Unmet medical needs | −0.013 | −0.019 | ||||

| Behavioral Characteristics | ||||||

| Impulsivity | −0.028* | −0.034* | ||||

| Exposure to violence | −0.102* | −0.037 | ||||

| Violent perpetration | −0.124*** | −0.084*** | ||||

| Neighborhood Characteristics | ||||||

| Neighborhood disadvantage | −0.107** | −0.059 | ||||

| Proportion residing in urban area | 0.016 | −0.083 | ||||

| Proportion residents in same house 5 years prior | −0.187 | −0.268 | ||||

| Level-2 between-person covariates | ||||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Male | — | — | ||||

| Female, intercept | −0.150 | 0.331*** | ||||

| Female, age | 0.114*** | — | ||||

| Female, age2 | −0.005† | — | ||||

| Race, ethnicity, and nativity | ||||||

| White | — | — | ||||

| Black, intercept | −1.003*** | −0.634*** | ||||

| Black, age | 0.078* | — | ||||

| Black, age2 | −0.006* | — | ||||

| Hispanic | −0.571*** | −0.433*** | ||||

| Asian | −0.340*** | −0.157** | ||||

| American Indian/Other race | −0.767*** | −0.517*** | ||||

| Foreign born | −0.076 | −0.281*** | ||||

| Family structure | ||||||

| Two biological married parents | — | — | ||||

| Two parents, unmarried | −0.230*** | −0.115* | ||||

| Single parent | −0.218*** | −0.089* | ||||

| Other family structure | −0.453*** | −0.243*** | ||||

| Family SESb | 0.103*** | 0.062*** | ||||

| Years in the neighborhood | 0.060*** | 0.033* | ||||

| Age at Wave Ib | −0.136*** | −0.111*** | ||||

| Mental and Physical Health | ||||||

| Average depression, intercept | −1.532*** | −1.351*** | ||||

| Average depression, age | 0.126** | 0.123** | ||||

| Average depression, age2 | −0.011** | −0.010** | ||||

| Average self-rated physical health, intercept | 0.238*** | 0.258*** | ||||

| Average routine physical care, intercept | 0.220*** | 0.165** | ||||

| Average unmet medical needs, intercept | −0.050 | 0.072 | ||||

| Behavioral Characteristics | ||||||

| Average impulsivity, intercept | 0.186*** | 0.010*** | ||||

| Average exposure to violence, intercept | −1.161*** | −0.319*** | ||||

| Average exposure to violence, age | 0.132* | — | ||||

| Average exposure to violence, age2 | −0.008 | — | ||||

| Average violent perpetration, intercept | −0.062 | −0.001 | ||||

| Average violent perpetration, age | −0.058* | −0.060** | ||||

| Average violent perpetration, age2 | 0.004† | 0.004* | ||||

| Neighborhood Characteristics | ||||||

| Average neighborhood disadvantage, intercept | −0.518*** | −0.270*** | ||||

| Average neighborhood disadvantage, age | 0.046** | 0.042* | ||||

| Average neighborhood disadvantage, age2 | −0.004* | −0.003* | ||||

| Average proportion residing in urban area | −0.038 | 0.266*** | ||||

| Average proportion residents in same house 5 years prior | −0.331* | −0.217 | ||||

| Variance component | 0.964 | 0.850 | 0.851 | 0.919 | 0.897 | 0.718 |

| χ2 | 21072.016*** | 19893.520 | 19752.284 | 20496.400 | 20221.586 | 18619.594 |

Notes:

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001 (two-tailed tests).

n = 48,864 observations, 20,103 respondents.

Indicates variables are group-mean centered around each individual

Indicates variables are grand-mean centered

FIGURE 1.

PREDICTED ODDS OF EXPECTING TO SURVIVE TO AGE 35

Since our analyses were concerned with assessing the predictors of adolescent and young adult survival expectations, we estimated a series of conditional hierarchical linear growth models, entering the individual and neighborhood dimensions of adolescent survival expectations separately (Models 2–5, Table 2), and then entering all measures together in a final model (Model 6). Initially, intercept and slope terms for the effect of the independent variables were estimated as random effects, allowed to vary across respondents; however, there was no significant between-person variation in the slope of impulsivity, physical health indicators, or urbanicity and residential stability with age, and so these slope terms were fixed in the models presented below.

Model 2 examines the possible mental and physical health components of adolescent and young adult survival expectations. Variation in depression over time was negatively associated with survival expectations, such that as an individuals’ depression increased over time, relative to their average, their odds of expecting to survive to age 35 were diminished (b = −0.554, p < 0.001). A 1-unit increase in depressive symptoms, relative to one’s average depression, was associated with a 42.5% decrease in the odds of expecting to survive to age 35 [(exp(−0.554)−1)*100]. Between-person variability in average depression was also negatively associated with initial survival expectations at age 12 (b = −1.532, p < 0.001) and change in expectations with age (b = 0.126, −0.011, p < 0.01).

Among the indicators of physical health, only self-rated health was associated with within-person change in survival expectations, such that improvements in one’s self-rated health over time were associated with higher odds of expecting to survive to age 35 (b = 0.135, p < 0.001). Between-person average ratings of health were also positively associated with expecting to survive. For instance, adolescents’ whose average self-rated health at age 12 was one-unit above the grand sample mean had a 26.9% higher odds of expecting to survive to age 35 [(exp(0.238)−1)*100]. Between-person differences in average receipt of routine physical care were associated with differences in survival expectations at age 12 (the intercept), but average unmet medical needs was not, and neither were associated with between-person differences in change in survival expectations over time.

Several demographic characteristics were associated with between-person differences in survival expectations (Model 3). At age 12, relative to non-Hispanic White adolescents, racial and ethnic minority youth had lower odds of expecting to survive, with Black youths’ change in survival expectations with age (slope) significantly differing from their White peers. Females did not significantly differ from males with respect to initial survival expectations, although they did display a different change with age. Females’ expected chances of surviving to age 35 increased with age at a faster rate than males’, as evidenced by the positive female*age (0.114***) term; however, this gap between males and females narrowed as, with age, males’ odds of expecting to survive to age 35 increased—this is evidenced by the negative female*age2 term (−0.005†).Youth living with two unmarried parents, a single parent, or in some other family structure all reported lower odds of expecting to survive, relative to their peers from two biological parent, married households. Finally, family socioeconomic status was positively associated with expecting to survive, as was number of years spent in ones’ neighborhood. Surprisingly, although the overall trend was an increase in the odds of expecting to survive with age (as shown in Model 1 and the Figure), respondents who were older at their Wave I interview were less likely than younger respondents to report expecting to survive.

Model 4 introduces individuals’ neighborhood characteristics as time-varying, and results indicate that as within-person neighborhood disadvantage increased over time, the odds of expecting to survive to age 35 decreased (b = −0.107, p < 0.01). Neighborhood disadvantage was also significantly associated with between-person differences in initial odds of expecting to survive, and change with age. Urbanicity and residential stability were not associated with within-person change in survival expectations, but residential stability was negatively associated with between-person differences in survival expectations.

As we discussed above, youth in disadvantaged neighborhoods are particularly at risk for experiencing violence—witnessing violent acts, being violently victimized, perpetrating violent acts, or placing themselves in other risky or dangerous situations. We examined the impact of these situational and behavioral characteristics in Model 5. Within-person increase in impulsivity with age was associated with a decrease in the odds of expecting to survive (b = −0.028, p < 0.05). Both exposure to violence (b = −0.102, p < 0.05) and perpetrating violent acts (b = −0.124, p < 0.001) undermined within-person survival expectations over time. Increases above one’s own average in exposure to violence were associated with a 9.7% decrease in the odds of expecting to survive to age 35 [(exp(−0.102)−1*100], and with each increase in violent acts perpetrated there was an 11.7% decline in within-person odds of expected survival. Further, between-person differences in average levels of impulsivity, exposure to violence, and violent perpetration were also significantly associated with survival expectations. Adolescents who were more impulsive at age 12 were actually more likely than their less impulsive peers to expect to survive to age 35 (b = 0.186, p < 0.001), and individuals exposed to violence had lower odds of expected survival than their non-victimized counterparts. Persons above the grand mean on violent perpetration did not significantly differ from non-violent peers with respect to initial survival expectations, although their change in survival expectations with age was significantly different.

The final model (Model 6) includes all measures simultaneously. Many of the significant relationships observed in the individual models remained significant, although for parsimony, between-person indicators that were no longer significant on the slope in the final model were excluded. Depression, self-rated physical health, and routine physical care were significantly associated with within-person variation in survival expectations, with depression diminishing survival expectations, and self-rated health and routine care bolstering expectations. Impulsivity and violent perpetration continued to undermine within-person survival expectations; exposure to violence was no longer significant in the final model (a series of stepwise models [not shown] indicated that this effect was explained largely by violent perpetration and depression). Within-person change in neighborhood disadvantage was no longer associated with survival expectations, once demographic indicators of group-based differences in health and well-being (race and ethnicity and family SES) were included.

Mental and physical health, impulsivity, exposure to violence, violent perpetration, and neighborhood characteristics remained significantly associated with between-person variation in survival expectations. For example, youth with above average depression reported lower odds of expected survival than their less depressed peers; youth who rated themselves as in better physical health and received routine care reported higher odds of survival; youth exposed to violence reported lower odds of survival than peers not experiencing violence; and youth living in neighborhoods with above average disadvantage reported lower odds of survival than their more advantaged peers. Neighborhood urbanicity was not associated with survival expectations when modeled independently (Model 4), but became significant in the final model—this was because the effect was suppressed by Hispanic ethnicity, as Hispanic youth reported lower odds of survival but were also more likely to live in urban areas.

Discussion

Thinking about the future and mapping out a coherent plan for ones’ life are key developmental tasks during adolescence, and are important factors as youth approach the transition to adulthood (Crockett & Bingham, 2000; Greene, 1990; Young, 1999). Individuals who feel uneasy about the certainty of their futures, or who sense a lack of control may not have high expectations of living long, successful lives. The present study examined the construct of youth survival expectations, with particular attention to the role of neighborhood contexts, and situational and behavior correlates (e.g., exposure to violence, own violent perpetration, diminished mental and physical health) often faced by youth in disadvantaged environments.

Findings revealed that survival expectations could be attributed to both individual and neighborhood characteristics. Importantly, both between-person and within-person differences in neighborhood disadvantage were found to be associated with youth survival expectations. Most consistent was the association of between-person neighborhood differences. Averaging across adolescence and early adulthood, those living in disadvantaged neighborhoods were found to have lower survival expectations than those in more advantaged contexts. This association remained significant with controls for a wide range of other demographic and individual characteristics. This finding is consistent with research into the durable nature of neighborhood inequalities in the United States (Quillian, 2003; Sampson & Morenoff, 2006; Sampson & Sharkey, 2008; Sharkey, 2008; Timberlake, 2007). Our finding that youth caught in the trap of poor neighborhoods were uncertain about their survival into adulthood is also consistent with previous ethnographic work within disadvantaged contexts (e.g., Young, 1999).

In addition to the stable nature of neighborhood inequalities, within-person increases in neighborhood disadvantage were also associated with diminished survival expectations. These associations, however, became statistically non-significant in the final model that controlled for demographics and variables representing within-person changes in situational and behavioral characteristics. For instance, changes in perceptions of physical health and depression were associated with changes in survival expectations in expected ways. So too were changes in youths’ own violence and impulsivity. Though a formal test of mediation was beyond the purpose of this analysis, theory and past research strongly suggest that disadvantaged neighborhoods produce just such physical weathering, stress, and violence.

The finding that changes in neighborhood disadvantage were associated with survival expectations is also consistent with findings from the Moving to Opportunity Demonstration (MTO), an important experimental study of neighborhoods and residential transitions. Of perhaps most relevance are findings from MTO that suggest that one of the biggest benefits of moving to more advantaged neighborhoods was reduced crime and an improved sense of safety (Katz, Kling, & Liebman, 2001 2001). MTO research also suggests the possibility of gender differences in neighborhood effects, with females moving to better neighborhoods appearing to benefit the most with respect to well-being, and, in particular, an increased sense of safety (Popkin, Leventhal, & Weismann, 2010). Future research on the connections between changes in neighborhood disadvantage and survival expectations, as well as a consideration of potential gender differences, is clearly warranted.

One somewhat unexpected finding was that between-person differences in neighborhood stability were associated with lower average survival expectations. Future research might examine whether this association varies by neighborhood disadvantage. Such moderation is suggested by other research in which neighborhood stability in a disadvantaged context may represent an inability to escape poverty (Ross, Reynolds, & Geis, 2000; see also Duncan & Aber, 1997).

The finding that both stable and changing characteristics are associated with survival expectations during the transition to adulthood is consistent with the life course perspective (Settersten et al., 2005; Shanahan, 2000). Here we focused primarily on neighborhood contexts. Future research should explore how other transitions in early adulthood are associated with survival expectations, particularly for youth from disadvantaged contexts. For example, does moving from a disadvantaged or dangerous context improve one’s survival expectations? Or do other transitions such as pursuit of higher education, entry into full-time employment, or family formation change one’s perspective on the future and hence survival expectations. Within research on crime and violence, such transitions are found to serve as potential turning points that may redirect the life course (Sampson & Laub, 1993).

In light of these findings, there are a few limitations that should be noted. For instance, Add Health is a school-based study, and therefore adolescents most at risk of having diminished survival expectations may have dropped out of school, and thus would be missing from our analyses. Also, one key challenge for researchers interested in the effects of neighborhood context is disentangling neighborhood effects from selection effects—possible unobserved individual (or family) characteristics that may be associated with selection into neighborhoods and affect outcomes, rendering neighborhood effects spurious. Thus, while our observation of both between-person and within-person differences in neighborhood disadvantage and exposure to violence is evidence of a neighborhood effect, we recognize that the possibility of unobserved heterogeneity remains.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study shows that adolescent survival expectations are not randomly distributed, nor are they solely a result of adolescent misperceptions or individual characteristics. Rather, the findings show that disadvantaged youth—particularly those living in poor neighborhoods, exposed to high levels of violence, and from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds—face a very different transition to adulthood than do more advantaged youth. One fruitful avenue for future research would be to examine whether (and how) the effect of neighborhood disadvantage on survival expectations is conditioned by the focal variables explored here—exposure to violence, violent perpetration, mental and physical health—and also to explore if the effect of neighborhood disadvantage varies across key demographic groups (e.g., by gender, race and ethnicity, family SES). Given the developmental significance of this key transitional period of the life course, both research and public health policy should strive to identify ways to assist disadvantaged youth in imagining more promising and healthy futures.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Center for Family and Demographic Research, Bowling Green State University, which has core funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24HD050959-08). This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Contributor Information

Raymond R. Swisher, Department of Sociology, Bowling Green State University, 214 Williams Hall, Bowling Green, OH 43403.

Tara D. Warner, Department of Sociology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 705 Oldfather Hall, Lincoln, NE 68588-0324.

References

- Aisenberg Eugene, Herrenkohl Todd. Community violence in context: Risk and resilience in children and families. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:296–315. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel Carol S, Sucoff Clea A. The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;45(3):293–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett Jeffrey Jensen. Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman Peter, Jones Jo, Udry J Richard. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research design. 1997 doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhelath/design.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellair Paul E, McNulty Thomas L. Beyond the bell curve: community disadvantage and the explanation of black-white differences in adolescent violence. Criminology. 2005;43(4):1135–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Billy John OG, Wenzlow Audra T, Grady William R. National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, Wave I and II Contextual Database. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky Iris Wagman, Ireland Marjorie, Resnick Michael D. Health status and behavioral outcomes for youth who anticipate a high likelihood of early death. Pediatrics. 2009;124:81–88. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezina Timothy, Tekin Erdal, Topalli Volkan. "Might not be a tomorrow": A multimethods approach to anticipated early death and youth crime. Criminology. 2009;47(4):1091–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Bulanda Jennifer Roebuck, Zhang Zhenmei. Racial-ethnic differences in subjective survival expectations for the retirement years. Research on Aging. 2009;31(6):688–709. [Google Scholar]

- Bursik Robert J, Grasmick Harold G. Neighborhoods and crime: The dimensions of effective community control. New York: Lexington Books; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Burton Linda M. One step forward and two steps back: Neighborhoods, adolescent development, and unmeasured variables. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, editors. Does it take a village? Community effects on children, adolescents, and families. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell Roslyn M, Wiebe Richard P, Cleveland H Harrington. The influence of future certainty and contextual factors on delinquent behavior and school adjustment among African American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(4):591–602. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke Christina A, Miller Tim, Chang Ellen T, Yin Daixin, Cockburn Myles, Gomez Scarlett L. Racial and social class gradients in life expectancy in contemporary California. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;70:1373–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen John A. Adolescent competence and the shaping of the life course. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;96:805–842. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett Lisa J, Bingham C Raymond. Anticipating adulthood: Expected timing of work and family transitions among rural youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10(2):151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe Robert. Introduction to Volume 1, Childhood and Adolescence. In: Carr D, editor. Encylopedia of the Life Course and Human Development, Volume 1. Detroit: Gale Cengage Learning; 2009. pp. xix–xxiii. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona Carolyn E, Wallace Gail, Wesner Kristin A. Neighborhood characteristics and depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15(4):188–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitle David, Turner R Jay. Exposure to community violence and young adult crime: The effects of witnessing violence, traumatic victimization, and other stressful life events. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2002;39:214–237. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott Glen R, Feldman S Shirley. Capturing the adolescent experience. In: Feldman SS, Elliot GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett Susan T, Bauman Karl E, Hussong Andrea, Faris Robert, Foshee Vangie A, Cai Li. The peer context of adolescent substance use: findings from social network analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(2):159–186. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor David, Turner Heather, Ormrod Richard, Hamby Sherry, Kracke Kristen. Children's exposure to violence: A comprehensive national survey Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fischhoff Baruch, de Bruin Wandi Bruine, Parker Andrew M, Millstein Susan G, Halpern-Felsher Bonnie L. Adolescents' perceived risk of dying. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischhoff Baruch, Parker Andrew M, De Bruin Wandi Bruine, Downs Julie, Palmgren Claire, Dawes Robyn, Manski Charles F. Teen expectations for significant life events. The Public Opinion Quarterly. 2000;64(2):189–205. doi: 10.1086/317762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores Glenn. Racial and ethnic disparities in the health and health care of children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e979–e1020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster Holly, Hagan John, Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. Growing up fast: Stress exposure and subjective "weathering" in emerging adulthood. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49:162–177. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg Frank F. The sociology of adolescence and youth in the 1990s: A critical commentary. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:896–910. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell Elizabeth, Furstenberg Frank F., Jr . The transition to adulthood during the twentieth century: Race, nativity, and gender. In: Settersten RA Jr, Furstenberg FF Jr, Rumbaut R, editors. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. pp. 29–75. [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus Arline T. The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infancts: Evidence and speculations. Ethnicity & Disease. 1992;2:207–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus Arline T. Black/white differences in the relationship of maternal age to birthweight: A population-based test of the weathering hypothesis. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;42(4):589–597. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus Arline T, Bound John, Waidmann Timothy A, Colen Cynthia G, Steffick Diane. Inequality in life expectancy, functional status, and active life expectancy across selected black and whie populations in the United States. Demography. 2001;38:227–251. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson Chris L, Morris Sara Z, Beaver Kevin M. Secondary exposure to violence during childhood and adolescence: Does neighborhood context matter? Justice Quarterly. 2009;26:30–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson Michael R, Hirschi Travis. A general theory of crime. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Greene AL. Great expectations: Constructions of the life course during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1990;19(4):289–306. doi: 10.1007/BF01537074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding David J. Collateral consequences of violence in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Social Forces. 2009;88:757–784. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris Kathleen Mullan, Duncan Greg J, Boisjoly Johanne. Evaluating the role of "nothing to lose" attitudes on risky behavior in adolescence. Social Forces. 2002;80(3):1005–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Horney Julie, Osgood D Wayne, Marshall Ineke Haen. Criminal careers in the short-term: intra-individual variability in crime and its relation to local life circumstances. American Sociological Review. 1995;60(5):655–673. [Google Scholar]

- Hurd Michael D, McGarry Kathleen. The predictive validity of subjective probabilities of survival. The Economic Journal. 2002;112:966–985. [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38(1):21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson Patrick E, Romer Dan. Unrealistic fatalism in U.S. youth ages 14 to 22: Prevalence and characteristics. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Monica Kirkpatrick, Mollborn Stefanie. Growing up faster, feeling older: Hardship in childhood and adolescence. Social Psychological Quarterly. 2009;72:39–60. doi: 10.1177/019027250907200105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Kling JR, Liebman JB. Moving to opportunity in Boston: Early results of a randomized mobility experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2001;116:607–654. [Google Scholar]

- Kotlowitz Alex. There are no children here: The story of two boys growing up in the other America. New York: Doubleday; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kronenfeld Jennie Jacobs. Health differentials/disparities, childhood and adolescence. In: Carr D, editor. Encylopedia of the Life Course and Human Development. Detroit, MI: Gale Cengage Learning; 2009. pp. 220–226. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal Tama, Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(2):309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin Gayla, Gordis Elana B. The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:445–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon Susan D, Felix Erika D, Halpert Jane A, Petropoulos Lara AN. Community violence exposure and aggression among urban adolescents: Testing a cognitive mediator model. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37:895–910. [Google Scholar]

- Mello Zena R, Swanson Dena P. Gender differences in African American adolescents' personal, educational, and occupational expectations and perceptions of neighborhood quality. Journal of Black Psychology. 2007;33(2):150–168. [Google Scholar]

- Minino Arialdi M. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. Mortality among teenagers aged 12–19 years: United States, 1999–2006: NCHS Data Brief No. 37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John, Ross Catherine E. Socioeconomic status and subjective life expectancy. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2000;49(3):133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Osofsky Joy D. The effects of exposure to violence on young children. American Psychologist. 1995;50(9):782–788. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.9.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parente Maria E, Mahoney Joseph L. Residential mobility and exposure to neighborhood crime: Risks for young children's aggression. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37:559–578. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin SJ, Leventhal T, Weismann G. Girls in the 'hood: How safety affects the life chances of low-income girls. Urban Affairs Review. 2010;45:715–744. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt Travis C, Turner Michael G, Piquero Alex. Parental socialization and community context: A longitudinal analysis of the structural sources of low self-control. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2004;41:219–243. [Google Scholar]

- Quillian Lincoln. How long are exposures to poor neighborhoods? The long-term dynamics of entry and exit from poor neighborhoods. Population Research and Policy Review. 2003;22:221–249. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush Stephen W, Bryk Anthony S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods, Second Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Egerter S, editors. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Overcoming obstacles to health. Princeton, NJ: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E, Mirowsky John. Family relationships, social support and subjective life expectancy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;51(3):469–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J, Laub John H. Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points through Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J, Morenoff Jeffrey D. Durable inequaltiy: Spatial dynamics, social processess, and the persistence of poverty in Chicago neighbohroods. In: Bowles S, Durlauf SN, Hoff K, editors. Poverty Traps. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2006. pp. 176–202. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J, Morenoff Jeffrey D, Gannon-Rowley Thomas. Assessing "neighborhood effects": Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;51(1):443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J, Sharkey Patrick. Neighborhood selection and the social reproduction of concentrated racial inequality. Demography. 2008;45(1):1–29. doi: 10.1353/dem.2008.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa Angela. Community violence exposure in a young adult sample: Lifetime prevalence and socioemotional effects. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:36–53. doi: 10.1177/0886260505281661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten Richard A, Jr, Furstenberg Frank F, Jr, Rumbaut Ruben., editors. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan Michael J. Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: Variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:667–692. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey Patrick. The intergenerational transmission of context. American Journal of Sociology. 2008;113:931–969. [Google Scholar]

- Singer Judith D, Willett John B. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- South Scott J, Crowder Kyle D. Neighborhood effects on family formation: Concentrated poverty and beyond. American Sociological Review. 1999;64:113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Swisher Raymond. User documenation for the Add Health Contextual Database, Wave III. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale Brent, Silver Eric. Neighborhoods and self-control: Toward and expanded view of socialization. Social Problems. 2009;56:205–222. [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake Jeffrey M. Racial and ethnic inequality in the duration of children's exposure to neighborhood poverty and affuence. Social Problems. 2007;54:319–342. [Google Scholar]