Abstract

Background and scope

The focus of this review is on institutionalized children, one of the most inequitably and severely treated groups of children. Although institutions vary, many share some common characteristics, including large groups, high children: caregiver ratios, many and changing caregivers, and caregiver-child interactions that lack warm, sensitive, contingently-responsive, and child-directed behaviors. Resident children develop poorly physically, mentally, and social-emotionally, but those adopted from institutions display substantial catch-up growth in many domains of development. If they are adopted at an early age, there have been no long-term consequences of institutionalization yet measured; but if institutionalization is prolonged, they display higher rates of long-term deficiencies and problems in many domains.

Methods

This review is based on a database search of the literature, focusing on the development of children while residents, and the development of post-institutionalized children who have been transitioned from institutions to family care. It also draws on the reports and findings of the St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Intervention.

Findings

A combination of theories pertaining to attachment (especially caregiver attachment to the infant/toddler), chronic stress, and genetics may explain these outcomes. It appears that caregiver-child interactions are a major contributor to children’s outcomes, and interventions in institutions that improve such interactions produce substantial increases in children’s physical, mental, and social-emotional development, including for children with disabilities.

Conclusions

Deinstitutionalization and the creation of comprehensive professional child welfare systems emphasizing family care alternatives is a preferred goal, but this is likely to take many low-resource countries decades to develop. If substantial numbers of children remain in institutions despite best efforts to find families for them, improving the institutions might help to provide all the children with the best care possible under the circumstances.

Keywords: Residential care, orphans, looked-after children, fostering, adoption, child development

Introduction

Professionals in the mental health field work with children reared in atypical and extreme environments. These may be within the context of their families, such as those reared in extreme poverty, abusive and neglectful homes, families in which there are parental mental health and substance abuse issues, and those plagued by conflict and violence. Others are reared out of their family context, such as in homeless shelters, camps and villages, poor foster and kinship care, and in institutions. Although each of these environments has its own unique characteristics, they often share some common features, and children reared in these environments also share higher rates of some common deficiencies and problems. While glib generalizations from institutionalized children should be avoided, there is enough communality across these situations to provide a broader context for the research on institutionalized and post-institutionalized children that follows.

Characteristics of institutions worldwide

There are no systematic, representative, and accurate data available, but estimates suggest from 2 (USAID, 2009) to 8 million (Human Rights Watch, 1999) children live in institutions worldwide. Most of these are in Eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Africa; there are fewer, but they also exist in Western Europe and North America. Unfortunately, the number of children residing in institutions is increasing, in part because of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, plus a decline in international adoptions, in part because of reported corruption, profiteering, and inadequate monitoring of adopted children’s well-being.

Characteristics of institutions

This review will focus on institutions that house children from birth -4/6 years of age, the published literature on the development of children while residents, and the development of post-institutionalized (PI) children who have been transitioned from institutions to family care.

The institutions in this literature vary from country to country within a country and over time within a country; but there are some commonly reported characteristics (Rosas & McCall, in press). For example, the physical environments can be quite minimal, although some are adequate. Children are typically raised in large groups (Ns = 9–16+), but some wards can house 50–60 infants in a single room. Within a ward, children are similarly aged, and children with disabilities tend to be kept in separate wards or separate institutions. Further, children are often moved periodically to a new ward of different peers and caregivers, such as when they reach a developmental milestone (crawl or walk). Children: caregiver ratios tend to be high, roughly 6–8+ to 1, and sometimes higher, even in wards of young infants. Further, there are many and changing caregivers, some of whom may work long shifts (24 hours) and then are off for three days. This caregiver scheduling, turnover, vacations that may be high as 50–60 days per year, plus ward transitions mean that children can experience 60–100 different caregivers by the time they are 19 months old (St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008). Finally, and perhaps most importantly, caregiver-child interactions tend to be limited, perfunctory, and business-like with a minimum of warm, sensitive, responsive interactions (Rosas & McCall, in press; St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005).

Resident children’s development

Not surprisingly, resident infants and young children develop poorly in nearly every domain. Meta-analyses of numerous studies indicate that institutionalized children average 1.0–1.5 standard deviations below the mean for parent-reared children with respect to physical growth and behavioral/mental development (van IJzendoorn, Bakersman-Kranenburg, & Juffer, 2007; van IJzendoorn, Luijk, & Juffer, 2008; van IJzendoorn et al., 2011) as well as displaying a variety of social and behavioral problems (Juffer et al., 2011). Of course there is variability, and children in a few institutions can be developmentally better (e.g., Dobrova-Krol, van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Juffer, 2010, Gavrin & Sacks, 1963; Vorria et al., 2003; Wolff & Fesseha, 1998) or substantially worse (e.g. St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005, 2008; Groark, McCall, Fish, & The Whole Child International Team, 2011).

Institutionalized children also commonly display certain specific behaviors that are rare among parent-reared children, such as stereotypies or self-stimulation (e.g., rocking, head banging, arm waving), problems with attention and activity control, internalizing and externalizing behavior, high rates of disorganized or unscoreable attachment on the Strange Situation Procedure, and indiscriminate friendliness (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2011). One study (Zeanah et al., 2009) has systematically assessed psychiatric disorders at 54 months of age in contemporary Bucharest institutions, finding three to four times as many institutionalized children as parent-reared children displaying any psychiatric disorder, any externalizing and internalizing disorder, ADHD, oppositional defiant or conduct disorder, and any anxiety disorder.

The Development of Post-Institutionalized (PI) Children Reared in Families

A substantial literature pertains to the development of children who spent the first several months or years of life in institutions and are then transitioned to families, predominately affluent and well-educated adoptive families in Europe and North America.

Catch-up growth

Most such children display substantial catch-up growth, often starting soon after adoption, in many general physical and behavioral (mental, social) domains (e.g., van IJzendoorn & Juffer, 2006), although the extent of catch-up may be more limited in some areas (i.e., gross motor: Roeber, Taber, Bolt, & Pollak, 2012; memory, executive functioning: Bos, Fox, Zeanah, & Nelson, III, 2009). This rather consistent finding provides retrospective testimony to the proposition that the institutional environment makes a substantial contribution to the delayed and adverse development of children within the institution, and that such poor development is not primarily associated with selected gene pool, adverse perinatal circumstances, and pre-institutional experience (McCall, 2011; Rutter et al., 2007, 2010).

Higher rates of deficient and problematic development

If children leave the institution at a relatively early age (see below), research has yet to demonstrate any lasting effect of having been institutionalized early in their lives. That is, such children do not display developmental deficiencies or behavioral problems at rates higher than would be expected of parent-reared children in their adoptive country (McCall, 2011; Zeanah, Gunnar, McCall, Kreppner, & Fox, 2011). This finding is remarkable, given the historical emphasis on the first months of life for “bonding’ and attachment, and it is perhaps surprising given the severely deficient, sometimes appalling, environments of some institutions.

Conversely, if children are adopted at a later age, the rates of deficient development and problems increase substantially in most domains (McCall, van IJzendoorn, Juffer, Groark, & Groza, 2011). Specifically, post-institutionalized (PI) children who have spent a more prolonged period of time in deficient institutions can have atypical brain development, especially in the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala (Nelson, Bos, Gunnar, & Sonuga-Barke, 2011), areas of the brain that have been linked with behavioral deficiencies and problems that are common in PI children. For example, they have higher rates of poorer executive functioning (i.e., attention, short-term memory, cognitive control/inhibition, sequencing and planning), higher rates of hyperactivity and quasi-autism, poorer emotional regulation, more anxiety, poorer attachment, more indiscriminate friendliness, and more co-morbidity of these problems (Bos et al., 2011; Juffer et al., 2011; Nelson et al., 2011; Rutter et al., 2010).

The timing of institutionalization

Although a large literature indicates that longer exposure to institutions is associated with more deficient development and higher rates of problems, only a few studies have explored the specific form of the association between ages of exposure and subsequent development. These few studies, however, present a provocative set of findings (Kreppner et al., 2007; McCall, 2011; Zeanah et al., 2011). First, children exposed to institutions, including very severely deficient institutions, between birth and 6+ months of age, do not display long-term deficiencies and problems at rates any higher than parent-reared children in the adoptive country, at least for the outcomes measured to date. Second, the risk of long-term deficiencies and problems increases rather precipitously in a step function of age at adoption, the latter often used as a surrogate for time in the institution. Third, the age at which the risk of long-term problems increases precipitously is earlier for children from very severely deficient institutions and somewhat later for those from less severely deficient institutions. Specifically, the rate increases after only 6 months for children from the very severely deficient 1990’s Romanian institutions (Kreppner et al., 2007), 18 months for children from less severely deficient St. Petersburg (Russian Federation) orphanages (Hawk & McCall, 2011; Merz & McCall, 2010a, 2010b; Merz, McCall, & Groza, 2012), and 24–27 mos. for children from a variety of institutions especially including children from China and South Korea who are thought to have had better early experiences (Merz & McCall, 2010a; Merz, McCall, & Groza, 2012). Fourth, once the risk increases, more prolonged exposure to the institution does not increase the risk, for a variety of behavior problems and executive functioning. These four principles undoubtedly depend in part on which outcomes are considered and how they are measured. For example, language deficiencies may arise more slowly during the second year (Windsor et al., 2011; Glaze, Koga, & The BEIP Group, 2007) and prolonged exposure may continue to limit general mental performance (e.g., Nelson, Zeanah, Fox, Marshall, Smyke, & Guthrie, 2007).

Explanatory Theories

This is a developmentally provocative and challenging set of findings. What is it about the institutions and the nature of development that might explain this set of curious phenomena? No one knows for certain but several theories and speculations have been proposed.

Attachment theory

The traditional theoretical orientation toward institutionalized children and their deficient development has been attachment theory. Early observations of institutionalized children by Burlingham and Freud (1944), Bowlby (1951), and Spitz (1945) provoked the speculation that such children lacked ‘mothering’ and the opportunity to form an attachment relationship with a caregiver. Further, the many and changing caregivers that such children experience limit the likelihood that they would readily develop conceptual models of their environment and how to behave effectively in it, and the lack of appropriate caregiving would also minimize their opportunities to develop self-regulation of their emotions and behavior (Bakersman-Kranenburg et al., 2011).

There are no direct tests of the role of attachment theory in explaining institutionalized and PI children’s development, for example, that children who have attachments in the institution develop physically and mentally better while residents and have lower rates of long-term problems if adopted. Instead, there are only observations that are ‘relatively consistent or inconsistent’ with the hypothesis. Consistent evidence includes the finding that institutionalized children rarely have organized or secure attachment relationships, and the few studies that have assessed relationships with the Strange Situation Procedure or a modification of it show that nearly three-fourths of institutionalized children have a disorganized or unscoreable attachment category (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2011). So, indeed, institutionalized children lack even organized, to say nothing of secure, attachment relationships with caregivers.

Further, the lack of a caregiver-child attachment relationship would seem to deny institutionalized children much of the stimulation and experiences that would likely contribute to typical development (McCall, 2011). For example, institutionalized children get limited stimulation of any kind. Infants spend a great deal of time lying in bed staring at a blank white ceiling or lying face down in their cribs or a large playpen with little stimulation. The many and changing caregivers contribute to inconsistency in the child’s interactions with caregivers, and peers are perhaps even more inconsistent. There is a lack of experience with contingencies of any kind, because caregiving duties are often done TO rather than WITH the infant, and caregiver interactions are often caregiver- rather than child–directed. Thus children have few experiences that would promote the perception of effectiveness or agency with the environment. Children are allowed to cry without being attended (Muhamedrahimov, 1999), so there is little opportunity to learn self-regulation. Presumably a caregiver-child relationship would provide appropriate stimulation and experiences instead of these common conditions of deprivation, and children reported to be ‘caregiver favorites’ indeed do somewhat better developmentally (Smyke et al., 2007).

But some evidence is not totally consistent with the attachment hypothesis. For example, Kreppner et al., (2007) reported that the risk for multiple long-term problems increased precipitously after only 6 months of exposure to the severely deficient 1990’s Romanian orphanages. This seems to suggest that whatever corrosive elements are operating in the institutional environment they can have an effect very early, presumably before the infant has an opportunity to develop a mature relationship with a caregiver. Six-month infants do not have object permanency, so while they are capable of recognizing a caregiver, out of sight is out of mind. Further, institutionalized children are mentally delayed (Van IJzendoorn et al., 2008), so one might assume that the mental skills necessary for a mature attachment are developed even later in institutionalized than in parent-reared children. Attachment, however, is a two-way street, and certainly institutionalized children suffer from a lack of an attached caregiver, even if the infant is too immature to develop much of an attachment to a caregiver. Further, more institutionalized children lack an attachment relationship than have long-term multiple problems, so something else is needed to explain why some children who lack early attachment relationships nevertheless do not develop long-term problems. These observations, especially the 6-month step function, prompted Kreppner et al. (2007) to suggest that something more fundamental and likely biological must be involved.

Chronic stress hypothesis

The chronic stress hypothesis may be that ‘more biological’ explanation, not only of why institutionalized children have higher rates of long-term problems but how the lack of early attachment relationships can produce adverse consequences. Chronic stress is widely invoked as a possible explanation of the consequences for children of prolonged exposure to a great variety of atypical and extreme environments, including those ACAMH members commonly experience in their clinical practice.

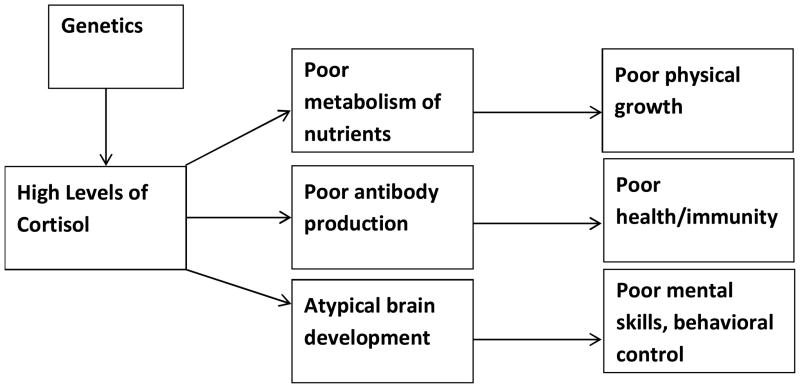

The chronic stress hypothesis is illustrated in Figure 1. Each link in the hypothesis has some basis in evidence, but typically such evidence is from animal research and studies with older children and adults, not studies of institutionalized infants and young children. Further, while evidence exists for single links in the hypothesized chain, the entire sequence has not been demonstrated (for reviews see Johnson & Gunnar, 2011; Nelson et al., 2011; Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007).

Figure 1.

Chronic Stress Hypothesis

Nevertheless, presumably the typical institutional environment is stressful for infants and young children because of the lack of consistent, warm, sensitive, contingent caregiving, which otherwise would reduce the stressful nature of the institutional environment. Consequently, institutionalized infants and young children should have higher levels of cortisol, a chemical produced by the body in response to chronic stress, and their hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) system would become dysregulated. Some children are more likely than others to be sensitive to stress, both because of genetic polymorphisms that dispose individuals to the effects of stress or produce resistance to it and presumably because of epigenetic activity in which the accumulation of adverse circumstances turns genes on or off with long-term consequences. Dysregulated HPA systems have been shown to produce a number of biological consequences (Johnson & Gunnar, 2011; Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007, 2008), including suppressing the production of growth hormones which might explain the growth failure of institutionalized children, suppressing the effectiveness of immunizations leading to lower levels of antibodies that may lead to poorer health, and altering brain development (prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala) which may be associated with poorer mental performance, executive functioning, and emotional control (Nelson et al., 2011).

Improving Orphanages

The attachment and chronic stress hypotheses both imply that long-term adverse effects might be avoided if caregiving in the institution were improved, because better caregiving should produce more organized and secure attachments as well as better HPA regulation (Gunnar & Quevedo 2007, 2008). Further, the preponderance of circumstantial evidence (McCall, 2011; Rutter et al., 2007, 2010) and comparisons of children randomly assigned to foster care vs. institutionalization (e.g., Nelson, et al., 2007) suggest that institutionalized children’s delayed development and long-term deficiencies and problems are likely more associated with the caregiving environment than with a variety of other potential confounds (J. N. McCall, 1999), such as a selected gene pool of the children who are sent to orphanages, perinatal risk circumstances, pre-institutional experience, and poor nutrition, sanitation, medical care. This general proposition could be partly tested by implementing an intervention in an institution that improved the caregiving environment but did not alter any of these potential confounds. Further, such a demonstration could provide a model of an institutional environment that could be implemented in other institutions around the world.

The St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Intervention

Such an intervention has been tried (St. Petersburg–USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005, 2008) with very positive results. The intervention had two major components, one was to train caregivers and encourage them to behave with the children in a more typical parental style (i.e., ‘love these children’) and the second was to change the institutional environment and employment patterns to support caregiver-child interactions by making the institution more ‘family-like’. Details of this intervention are presented in the accompanying text box.

Text box 1. Intervention Implemented in St. Petersburg (Russian Federation).

Training (‘Love these children’)

Be engaged with children

Encourage warm, sensitive, contingently-responsive caregiver-child interactions

Follow child’s lead

Engage in reciprocal verbal and non-verbal interactions and conversation

Display appropriate affect

Structural changes (More ‘family-like’ environment)

Reduce group size from 12–14 to 6–7 children

Reduce number of caregivers assigned to a group from 9–12 to 6

Assign 2 ‘primary’ caregivers per group, one of whom would be present most waking hours every day; assign 4 ‘secondary’ caregivers to each specific group who worked separate days

Integrate groups by age and disability status of children

Stop periodic transitions of children to new groups of peers and caregivers

Institute ‘family-hours’ once each in the morning and afternoon in which children remained in their group with their caregivers without visitors or specialists

Implement an in-house system of monitoring and supervision to encourage caregivers to implement training principles with children

‘Family-like environment’

Table 1 presents a comparison of the major elements of family life that one might suppose contribute to the family being an ideal environment for rearing infants and young children and compares those characteristics with the nature of many institutions. The contrast is striking, and sometimes when institution directors and major staff professionals see this comparison they are shocked (Groark & McCall, 2011). Directors and staff are well-meaning people, but they have worked in an environment with attitudes and policies that have existed for decades and few have stopped to question whether these conditions are in the best interests of the children in their care. For some, this table produces an epiphany, and they declare they need to do something to change the institutional environment. The structural change component of the St. Petersburg intervention (St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008) altered all of these characteristics (see text box).

Table 1.

Comparison of major characteristics of typical families and orphanages

| Characteristic | Families | Orphanages |

|---|---|---|

| Children per group | Few | Many |

| Ages, developmental status | Mixed | Not Mixed |

| Children: caregiver ratio | Low | High |

| Number of caregivers | Few | Many |

| Consistency of caregivers | High | Low |

| Warm, sensitive, responsive caregiving | High | Low |

Three institutional conditions

The training and structural changes were implemented in one institution for children birth to 4 years of age, although many left between 1 and 3 years of age. This condition was labeled T+SC, for Training Plus Structural Changes. A second institution received Training Only, called TO, and a third institution received No Intervention, called NoI.

Outcomes

Caregiving quality on the wards

A major issue with training caregivers is whether they actually implement the training in their behavior with children on the wards. The HOME inventory was used to measure the physical and the behavioral environment on the wards. Scores for the T+SC group rose immediately after the intervention had been completely implemented and stayed substantially higher than the other two groups throughout the study.

Children’s development

T+SC and TO children, both typically developing and those with disabilities, increased in height, weight, and chest circumference. Typically developing T+SC and TO children progressively displayed fewer functional limitations, and these physical benefits tended to be greater the longer the children were in the intervention, especially for T+SC children. NoI children did not improve on any of these measures.

Behavioral and mental development were assessed with the Battelle Developmental Inventory, and developmental quotients (DQs) increased for T+SC children from an average of 57 to 92=35 DQ points, perhaps the largest average increase in behavioral/mental development observed for any intervention in the literature. Children with disabilities rose from 23 to 42=19 DQ points on average, 27% of these children increased more than 30 points, and 14% increased more than 40 points. These are also among the largest improvements in the literature. For both groups of children, scores improved the longer they were in the intervention.

In caregiver-child free play sessions, typically developing T+SC and TO children displayed a higher quality of play, alertness, and self-regulation than NoI, and T+SC children showed more positive affect, social initiative, and communication than TO and NoI children – again more the longer they were in the intervention. Finally, T+SC children 11.5–18 months of age were more likely to be categorized as having an organized attachment to their favorite caregiver on a modified Strange Situation Procedure, and they were substantially less likely to be considered disorganized than TO and NoI children.

A mediational analysis demonstrated that 43% of children’s better behavioral/mental development was mediated by the better caregiving environment as reflected on the HOME inventory (Rosas et al., 2011).

Maintenance and sustainability

The St. Petersburg intervention demonstrates that institutions do not need to operate in the way most do and that encouraging caregivers to interact more appropriately with children in an environment that is made more family-like can produce very substantial improvements in the development of resident infants and toddlers. However, an issue is whether such a transformed institution can maintain the improved caregiving and continue to have graduates who display more typical behavioral/mental development after funding and support for the intervention terminates.

A recent study (McCall et al., in press) indicates that the T+SC institution has maintained for at least six years the same quality of care as reflected on the HOME as it had during the intervention. T+SC maintains its advantage over TO and NoI, and it has done so on the budget provided it and other institutions in St. Petersburg by the government. Moreover, the Battelle DQs of children departing the institutions reveal that T+SC children still maintained an advantage over children from the other two institutions. Interestingly, the DQs of children in all three institutions improved over the six-year period, perhaps because fewer children were sent to institutions but staff levels remained the same producing smaller groups and fewer children per caregiver in all three of the institutions (McCall et al., in press).

Long-term benefits

Unfortunately, although children who have left the three experimental institutions for families (adoptive, foster, and biological) are currently being studied, they are still too young to display much long-term benefit of having been in T+SC versus TO and NoI. After the follow-up studies began, research on PI children from St. Petersburg who had been adopted to the United States before any interventions were implemented demonstrated that higher rates of deficiencies and problems among children adopted at older ages were not reported by parents until the children were 10–12 years of age (Hawk & McCall, 2011; Merz & McCall, 2010a, 2010b), although measurements made directly on children can reveal deficiencies earlier (e.g., Bos et al., 2011; Roeber, Taber, Bolt, & Pollak, 2012). No child leaving the intervention institutions is this old yet. However, T+SC children have better parent-reported attachments than children from TO and NoI (Julian & McCall, 2012).

These results and those of similar interventions (Groark et al., 2012; McCall, Groark, Fish, Harkins, Serrano, & Gordon, 2010) indicate that institutions can be improved; the improvements can produce substantial increases in physical, mental, social, and behavioral development in both typically developing children and those with disabilities; and such benefits can be maintained for at least six years with no additional funds. Thus, we know how and can financially afford to improve institutions, but should we?

International Child Welfare Policies

Should We Improve Institutions?

Advocates for family-based alternative care and deinstitutionalization often bristle at the thought of improving institutions. They argue “we don’t want to improve institutions; we want to get rid of them,” and some stretch Moore and Moore’s (1977) opinion to argue that ‘any family is better than any institution.’ Further, advocates fear that improving institutions will deflect attention, energy, and resources of a country away from developing a family care alternative system.

There is some justification for these concerns. At least one study indicates that in terms of development, even children reared in families with substantial risk may be better than those reared in institutions as typically practiced (Dobrova-Krol et al., 2010). But other research demonstrates that community residential care is associated with better children’s outcomes than family care (predominantly kinship), at least for children 6–12 years of age in five low-resource countries (Whetten et al., 2009).

Challenges to Implementing Family Care

No one would deny that a worthy and appropriate goal is for ‘every child to live in a stable, loving family.’ Further, families typically come with the structural elements thought to be beneficial to children (e.g. Table 1) that might need to be implemented within a residential institution to produce similar developmental outcomes. In addition, although there is some cost to implementing a family care system (and some cost to changing institutions), once established family care is clearly cheaper to maintain and operate than institutions (Engle et al., 2011). Finally, a review of research on family vs. institutional care as currently practiced reveals that children’s outcomes are generally better for family care (i.e., adoption, foster care) than institutions (Julian & McCall, 2011).

Challenges

But depending on the circumstances of the country, creating an effective and comprehensive family care system may face a variety of challenges (Engle et al., 2011; Groza, Bunkers, & Gamer, 2011; McCall, 2011). For example, there may be cultural, political, historical aversions within a country to rearing someone else’s child, and there may be religious prohibitions against adoption. The result can be difficulty recruiting families to adopt or foster children. Creating appropriate incentives for parents to adopt or foster children is more difficult than it appears. For example, most countries are reluctant to pay parents to adopt children, despite the fact that adoption is the best alternative for such children (Julian & McCall, 2011). Also, providing financial incentives for low-income, single, or teenage mothers to keep their children simultaneously rewards having children out of wedlock, and some couples may deliberately not marry to receive such benefits. In addition, a professional social work infrastructure is needed to create an appropriate selection process for picking adoptive or foster parents, training them, monitoring and supporting them in the field, and helping them cope with the inevitable problems that some children from institutions are likely to have. Finally, typically developing infants and young children are likely to be placed in families first, which means that older children and those with disabilities are more likely to be left in the institutions while a comprehensive family care system is being developed.

The net effect of these challenges is that developing a comprehensive family care system will take time in many countries. Indeed, it took the United States several decades to deinstitutionalize and place children in families. More recently, Ukraine made a very substantial effort to deinstitutionalize and develop alternative family care. The president of the country was in favor of it, people in administrative positions were dedicated to this goal, and a variety of incentives and policies were created to support it. It seemed that Ukraine had everything going for it to succeed in this endeavor, but after five years of intensive effort, 1,750 children were adopted and 5,000 were placed in foster care, but 45,000 still remained in institutions (Groark, McCall, & Li, 2009).

Conclusions: what to do?

The literature indeed suggests that family care is likely to be the best alternative for most children (Julian & McCall, 2011), perhaps the easiest to create because families already have appropriate structural characteristics, and in the long run it is cheaper. But the literature also seems to suggest that it is the quality of care, perhaps more than the particular type of care, that is most important for children’s development. Further, a variety of historical, political, social, cultural, and religious circumstances may exist in a country that prolong the implementation process or even limit the success of family-based care of one kind or another.

Each country needs to develop its own solution. Family care has many advantages in many cultures, but it cannot be simply dropped into a country without regard to the circumstances of that locale. Further, whatever system a country adopts, it is likely to need a professional social work/child welfare infrastructure to implement and support it. One cannot simply throw financial incentives at individuals to rear children; technical expertise and support is needed.

In the near term, while family alternatives are being developed, many children are likely to remain in institutions. Depending on the numbers of such children and the pace of implementing family alternatives, improving institutions might support the development of substantial numbers of children, especially those with disabilities. Although improving institutions should not deflect attention and resources from establishing a family care system, it helps the country to develop a more immediately comprehensive system that benefits ALL children without permanent parents.

If countries were able to develop such a comprehensive system, Jack and Barbara Tizard would be pleased.

Key Points.

Infants, toddlers, and young children reared in typical institutions develop poorly physically, mentally, and social-emotionally.

If subsequently adopted or placed in foster care, most children display substantial catch-up growth in most domains of development, but more so if transitioned to family early.

Children adopted later may display higher rates of physical, mental, and behavioral deficiencies and problems.

Children develop better in adoptive or foster families, but the quality of caregiving is likely more important that the type.

Institutions might be improved as long as substantial numbers of children remain residents, but this should not diminish efforts to create family-care alternatives for all children.

Acknowledgments

This review article was invited by the journal following the presentation of some of the material as the 2012 Jack Tizard Memorial Lecture (ACAMH, June 2012, London), for which R.B.M. received travelling expenses; the final manuscript was subject to full peer review.

The author is indebted to contributions made principally by Christina J. Groark, PhD, as well as Jacqueline Dempsey, Larry Fish, Brandi Hawk, Megan Julian, Junlei Li, Emily Merz, and Johanna Rosas of the University of Pittsburgh; Rifkat Muhamedrahimov, and Oleg Palmov of St. Petersburg State University and Natalia Nikiforova of Baby Home 13, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation; and to funding provided by the US Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD 050212) (to McCall and Groark) and by Whole Child international (to Groark and McCall).

Footnotes

No other competing or potential conflicts of interest arise from the publication of this work.

References

- Bakermans-Kranenburg JJ, Steele H, Zeanah CH, Muhamedrahimov RJ, Vorria P, Dobrova-Krol NA, et al. Attachment and emotional development in institutional care: Characteristics and catch-up. In: McCall RB, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Groark CJ, Groza VK, editors. Children without permanent parents: Research, practice, and policy. 4. Vol. 76. 2011. pp. 62–91. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, Serial No 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos KJ, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, Nelson CA., III Effects of early psychosocial deprivation on the development of memory and executive functioning. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009;3:Article 16. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.016.2009. www.frontiersin.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos K, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Drury SS, McLaughlin KA, Nelson CA. Psychiatric outcomes in young children with a history of institutionalization. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2011;19(1):15–23. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2011.549773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Maternal care and mental health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1951. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlingham D, Freud A. Infants without families. London: Allen & Unwin; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrova-Krol NA, van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Juffer F. Effects of perinatal HIV infection and early institutional rearing on physical and cognitive development of children in Ukraine. Child Development. 2010;81:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle P, Groza V, Groark CJ, Greenberg A, Bunkers KM, Muhamedrahimov R. The situation for children without parental care and strategies for policy change. In: McCall RB, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Groark CJ, Groza VK, editors. Children without permanent parents: Research, practice, and policy. 4. Vol. 76. 2011. pp. 190–222. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, Serial No. 301. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrin JB, Sacks LS. Growth potential of preschool-aged children in institutional care: A positive approach to a negative condition. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1963;33:399–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1963.tb00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groark CJ, McCall RB, Li J. Characterizing the status and progress of a country’s child welfare reform. International Journal of Child & Family Welfare. 2009;4:145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Groark CJ, McCall RB. Implementing changes in institutions to improve young children’s development. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2011;32(5):509–525. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groark CJ, McCall RB, Fish LA The Whole Child International Team. Characteristics of environments, caregivers, and children in three Central American orphanages. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2011;32(2):232–250. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groark CJ, McCall RB, McCarthy SK, Eichner JC, Warner HA, Palmer K. Unpublished report, authors. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development; 2012. The effects of a social-emotional intervention on caregivers and children in five Central American institutions. [Google Scholar]

- Groza V, Bunkers KM, Gamer G. Ideal components and current characteristics of alternative care options for children outside of parental care. In: McCall RB, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Groark CJ, Groza VK, editors. Children without permanent parents: Research, practice and policy. 4. Vol. 76. 2011. pp. 163–189. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, Serial No. 301. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Quevedo K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Quevedo K. Early care experiences and HPA axis regulation in children: A mechanism for later vulnerability. Progress in Brain Research. 2008;167:137–149. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)67010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawk B, McCall RB. Specific extreme behaviors of post-institutionalized Russian adoptees. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(3):732–738. doi: 10.1037/a0021108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch world report 1999. New York, NY: Human Rights Watch; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DE, Gunnar MR. Growth failure in institutionalized children. In: McCall RB, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Groark CJ, Groza VK, editors. Children without permanent parents: Research, practice, and policy. 4. Vol. 76. 2011. pp. 92–126. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Serial No. 301. [Google Scholar]

- Juffer F, Palacios J, LeMare L, Sonuga-Barke EJS, Tieman W, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, et al. Development of adopted children with histories of early adversity. In: McCall RB, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Groark CJ, Groza VK, editors. Children without permanent parents: Research, practice, and policy. 4. Vol. 76. 2011. pp. 31–61. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, Serial No. 301. [Google Scholar]

- Julian MM, McCall RB. The development of children within alternative residential care environments. International Journal of Child & Family Welfare. 2011;3–4:119–147. [Google Scholar]

- Julian MM, McCall RB. Attachment and indiscriminate friendliness among adopted children exposed to a social-emotional intervention in an institution. Poster presented at the International Conference on Infant Studies; Minneapolis, MN. 2012. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- Kreppner JM, Rutter M, Beckett C, Castle J, Colvert E, Grootheues C, et al. Normality and impairment following profound early institutional deprivation: A longitudinal follow-up into early adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:931–946. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall JN. Research on the psychological effects of orphanage care: A critical review. In: McKenzie RB, editor. Rethinking orphanages for the 21st century. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB. Research, practice, and policy perspectives on issues of children without permanent parental care. In: McCall RB, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Groark CJ, Groza VK, editors. Children without permanent parents: Research, practice, and policy. 4. Vol. 76. 2011. pp. 223–272. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Serial No. 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB, Groark CJ, Fish LA, Harkins D, Serrano G, Gordon K. A social-emotional intervention in a Latin American orphanage. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2010;31:521–542. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB, Groark CJ, Fish L, Muhamedrahimov RJ, Palmov OI, Nikiforova NV. Maintaining a social-emotional intervention and its benefits for institutionalized children. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12098. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Groark CJ, Groza VK, editors. Children without permanent parents: Research, practice, and policy. 2011;76(4) Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, Serial No. 901. [Google Scholar]

- Merz EC, McCall RB. Behavior problems in children adopted from socially-emotionally depriving institutions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010a;38:459–470. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9383-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz EC, McCall RB. Parent ratings of executive functioning behavior in children adopted from psychosocially depriving institutions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010b;52(5):537–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02335.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz EC, McCall RB, Groza V. Unpublished manuscript, authors. University of Pittsburgh, Office of Child Development; Pittsburgh, PA: 2012. Parent-reported executive functioning in post-institutionalized children: A follow-up study. [Google Scholar]

- Moore RS, Moore DN. Better late than early. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Muhamedrahimov RJ. New attitudes: Infant care facilities in St. Petersburg, Russia. In: Osofsky JD, Fitzgerald HE, editors. WAIMH handbook of infant mental health. Vol. 1. Perspectives on infant mental health. New York, NY: Wiley; 1999. pp. 245–294. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, Bos K, Gunnar MR, Sonuga-Barke EJS. The neurobiological toll of early human deprivation. In: McCall RB, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Groark CJ, Groza VK, editors. Children without permanent parents: Research, practice, and policy. 4. Vol. 76. 2011. pp. 190–222. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, Serial No 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Smyke AT, Guthrie D. Cognitive recovery in socially deprived young children: The Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Science. 2007;318:1934–1940. doi: 10.1126/science.1143921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeber BJ, Tober CL, Bolt DM, Pollak SD. Gross motor development in children adopted from orphanage settings. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2012;54:527–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas JM, McCall RB. Characteristics of institutions, interventions, and resident children’s development. International Journal of Behavioral Development (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Rosas JM, McCall RB, Groark CJ, Muhamedrahimov RJ, Palmov OI, Nikiforova NV. Unpublished paper, authors. University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development; Pittsburgh, PA: 2011. Environmental quality as mediator between an institutional intervention and children’s developmental outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Colvert E, Kreppner J, Beckett C, Castle J, Groothues C, et al. Early adolescent outcomes for institutionally-deprived and non-deprived adoptees. I: Disinhibited attachment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(1):17–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Sonuga-Barke EJS, Beckett C, Castle J, Kreppner J, Kumsta R, et al. Deprivation-specific psychological patterns: Effects of institutional deprivation. 2010;75(1) doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2010.00550.x. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, Serial No. 295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyke AT, Koga SF, Johnson DE, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Nelson CA The BEIP Core Group. The caregiving context in institutional-reared and family-reared infants and toddlers in Romania. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(2):210–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz R. Anaclitic depression: An inquiry into the genesis of psychiatric conditions in early childhood-II. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 1946;2:313–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team. Characteristics of children, caregivers, and orphanages for young children in St. Petersburg, Russian Federation. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology: Special Issue on Child Abandonment. 2005;26:477–506. [Google Scholar]

- St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team. The effects of early social-emotional and relationship experience on the development of young children. 2008;72(3) doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2008.00483.x. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, Serial Number 291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USAID. US government and partners: Working together on a comprehensive coordinated and effective response to highly vulnerable children. Washington, DC: USAID; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. The Emanuel Miller Memorial Lecture 2006: Adoption as intervention. Meta-analytic evidence for massive catch-up and plasticity in physical, socio-emotional, and cognitive development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(12):1228–1245. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Juffer F. Plasticity of growth in height, weight and head circumference: Meta-analytic evidence for massive catch-up after international adoption. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28(4):334–343. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31811320aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van IJzendoorn MH, Luijk MPCM, Juffer F. Detrimental effects on cognitive development of growing up in children’s homes: A meta-analysis on IQ in orphanages. Merrill Palmer Quarterly. 2008;54:341–366. [Google Scholar]

- Van IJzendoorn MH, Palacios J, Sonuga-Barke EJS, Gunnar MR, Vorria P, McCall RB, LeMare L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Dobrova-Krol NA, Juffer F. Children in institutional care: Delayed development and resilience. In: McCall RB, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Groark CJ, Groza VK, editors. Children without permanent parents: Research, practice, and policy. 4. Vol. 76. 2011. pp. 8–30. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, Serial No 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorria P, Papaligoura Z, Dunn J, Van IJzendoorn MH, Steele H, Kontopoulou A, et al. Early experiences and attachment relationships of Greek infants raised in residential group care. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:1208–1220. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten K, Ostermann J, Whetten RA, Pence BW, O’Donnell K, Messa L, et al. A comparison of the well-being of orphans and abandoned children ages 6–12 in institutional and community-based care settings in five less wealthy nations. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor J, Benigno JP, Wing CA, Carroll PJ, Koga SF, Nelson CA, III, Zeanah CH. Effect of foster care on young children’s language learning. Child Development. 2011;82(4):1040–1046. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff PH, Fesseha G. The orphans of Eritrea: Are orphanages part of the problem or part of the solution? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1319–1324. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.10.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Egger H, Smyke AT, Nelson C, Fox N, Marshall P, et al. Institutional rearing and psychiatric disorders in Romanian preschool children. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:777–785. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08091438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Gunnar MR, McCall RB, Kreppner JM, Fox NA. Sensitive periods. In: McCall RB, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Groark CJ, Groza VK, editors. Children without permanent parents: Research, practice, and policy. 4. Vol. 76. 2011. pp. 147–162. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, Serial No 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]