Abstract

Background

The histology of epithelial “borderline lesions” of the breast, which have features in between atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), is well described, but the clinical behavior is not. This study reports subsequent ipsilateral breast events (IBE) in patients with borderline lesions compared with those with DCIS.

Methods

Patients undergoing breast-conserving surgery for borderline lesions or DCIS from 1997 to 2010 were identified from a prospective database. IBE was defined as the diagnosis of subsequent ipsilateral DCIS or invasive ductal carcinoma.

Results

A total of 143 borderline-lesion patients and 2,328 DCIS patients were identified. Median follow-up was 2.9 and 4.4 years, respectively. 7 borderline-lesion and 172 DCIS patients experienced an IBE. 5 year IBE rates were 7.7 % for borderline lesions and 7.2 % for DCIS (p = .80). 5 year invasive IBE rates were 6.5 and 2.8 %, respectively (p = .25). Similarly, when analyses were restricted to patients who did not receive radiotherapy, or endocrine therapy, or both, borderline-lesion and DCIS patients did not demonstrate statistically significant differences in rates of IBE or invasive IBE.

Conclusions

When compared with DCIS, borderline lesions do not demonstrate lower rates of IBE or invasive IBE. Despite “borderline” histology, a 5 year IBE rate of 7.7 % and an invasive IBE rate of 6.5 % suggest that the risk of future carcinoma is significant and similar to that of DCIS.

As suggested by Page et al and Rosai,1-4 atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) constitute somewhat arbitrary points along a continuum of ductal neoplasias, each with a different degree of atypia and proliferation. The existence of such a continuum allows for the possibility of “borderline lesions,” for example, epithelial histologies with too much atypia and proliferation to qualify for a diagnosis of ADH, but not enough to qualify for a diagnosis of DCIS. In 1992, although Page and Rogers attempted to standardize pathologic diagnostic criteria for DCIS and ADH, they noted, “There is no absolute or solitary division between ‘cancer yes’ and ‘cancer no.”5 Masood and Rosa recently stated that the “distinction of ADH and low nuclear grade DCIS…remains a diagnostic challenge.”6

While the existence of borderline lesions has been well described, the natural history and risk of subsequent breast cancers have not.4,6,7 ADH is considered a risk factor for the development of breast cancers; DCIS is considered the precursor of invasive breast cancer. No treatment is considered necessary for ADH; excision to clear margins is not required, and mastectomy and radiation are not indicated. Rather, discussion and consideration of risk-reduction options are standard, and the risk of subsequent breast cancers is equal in both breasts. In contrast, a woman with DCIS has a greater risk of subsequent ipsilateral breast cancer (either in situ or invasive) such that a diagnosis of DCIS mandates treatment. Standard of care includes complete excision and consideration of adjuvant radiotherapy and endocrine therapy.

When a lesion is “borderline,” reported as “markedly atypical ductal hyperplasia bordering on low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ” or “markedly atypical ductal hyperplasia focally reaching the level of DCIS,” a clinician faces an absence of data regarding its natural history. Knowledge of clinical outcomes for this entity would be helpful in counseling and managing such patients.

The aim of the present report is to describe clinical outcomes of women who underwent surgical excision of borderline lesions and to compare these outcomes to those for women diagnosed with DCIS during the same time period. Our hypothesis was that women with borderline lesions are less likely to be diagnosed with subsequent ipsilateral breast cancer than are women with DCIS.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

After obtaining approval from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center institutional review board, a prospectively maintained DCIS database for women undergoing breast-conserving surgery was queried to identify all patients with an epithelial borderline lesion or DCIS from 1997 through 2010. Pathology databases were also queried for any reports for patients with ADH or DCIS that included the terms “approach,” “border,” “near,” “at,” or “reach.” Histopathologic diagnoses were retrieved from original pathology reports after surgical excision. Cases with the definitive histopathologic diagnosis of “markedly atypical ductal hyperplasia bordering on low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ” or “markedly atypical ductal hyperplasia focally reaching the level of DCIS” were classified as epithelial borderline lesions. Lesions described as simply “atypical ductal hyperplasia” were not considered borderline lesions.

Clinical data were obtained from the DCIS database and the medical record. Family history was considered positive if either first-degree or second-degree relatives had breast cancer. Presentation was defined as clinical if there was a palpable mass, nipple discharge, or clinical signs of Paget’s disease. Margin status was categorized as negative, close (≤2 mm), or positive (borderline lesion or DCIS at ink). Patients with no residual disease in the re-excision specimen were considered to have negative margins. Nuclear grade of DCIS was defined as low, intermediate, or high. Cases described as “low/intermediate grade” were categorized as intermediate grade; cases described as “intermediate/high” were categorized as high grade. Use of adjuvant radiotherapy and endocrine therapy were recorded as “yes,” “no,” or assigned “unknown.” Follow-up for women in the prospective database is updated at least annually by contacting them by mail or phone and by review of the medical record.

A subsequent ipsilateral breast event (IBE) was defined as the diagnosis of an ipsilateral breast in situ or invasive carcinoma. In rare cases (n = 2), no information was available on whether the disease was in situ or invasive; these patients were said to have had an IBE of unknown type.

Statistical Analyses

Differences between groups were assessed using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (for continuous covariates) and chi-square tests (for categorical covariates). The primary clinical endpoint was an IBE. Patients who did not have an IBE were censored at last follow-up or death. The 5 year rates of IBE were determined using Kaplan–Meier methods. Competing risks survival analysis was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of ipsilateral invasive ductal carcinoma with in situ and unknown-type IBE as competing events. Comparisons were assessed using the log-rank test for IBE and Gray’s Test for invasive IBE. A p value less than .05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) and R 2.11.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

A total of 143 patients with borderline lesions and 2328 patients with DCIS were identified. Clinicopathologic characteristics (Table 1) and outcomes (Table 2) for the entire population and for the subset that did not receive adjuvant radiotherapy are presented. Median follow-up was 2.9 years (range, 0–13.0 years) for borderline lesions and 4.4 years (range, 0–14.2 years) for DCIS. There were no deaths from breast cancer in the borderline group. There were 3 deaths from breast cancer in the DCIS group; all had a diagnosis of contralateral invasive breast cancer.

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with borderline lesions and DCIS, for the entire population and those not receiving adjuvant radiation

| Entire population (n = 2471)

|

No-radiation cohort (n = 1046)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borderline lesion n (%) | DCIS n (%) | p value | Borderline lesion n (%) | DCIS n (%) | p value | |

| N | 143 (5.8) | 2328 (94.2) | 139 (13.3) | 907 (86.7) | ||

| Age (years), median (range) | 51 (20–85) | 57 (25–92) | <.001 | 51 (20–85) | 60 (25–92) | <.001 |

| Menopausal status | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| Premenopause/perimenopause | 73 (51.0) | 770 (33.1) | 71 (51.1) | 258 (28.4) | ||

| Postmenopause | 68 (47.6) | 1511 (64.9) | 66 (47.5) | 622 (68.6) | ||

| Unknown | 2 (1.4) | 47 (2.0) | 2 (1.4) | 27 (3.0) | ||

| Family history | .56 | .62 | ||||

| No | 88 (61.5) | 1391 (59.8) | 84 (60.4) | 531 (58.5) | ||

| Yes | 52 (36.4) | 914 (39.3) | 52 (37.4) | 361 (39.8) | ||

| Unknown | 3 (2.1) | 23 (1.0) | 3 (2.2) | 15 (1.7) | ||

| Initial presentation | .96 | .81 | ||||

| Clinical | 13 (9.1) | 216 (9.3) | 13 (9.4) | 91 (10.0) | ||

| Radiographic | 129 (90.2) | 2109 (90.6) | 125 (89.9) | 813 (89.6) | ||

| Unknown | 1 (.7) | 3 (.04) | 1 (.7) | 3 (.3) | ||

| Margin status | .006 | .22 | ||||

| Negative | 126 (88.1) | 1934 (83.1) | 122 (87.8) | 775 (85.4) | ||

| Close | 12 (8.4) | 313 (13.4) | 12 (8.6) | 100 (11.0) | ||

| Positive | 4 (2.8) | 80 (3.4) | 4 (2.9) | 31 (3.4) | ||

| Unknown | 1 (.7) | 1 (.04) | 1 (.7) | 1 (.1) | ||

| Nuclear grade | ||||||

| Low | 395 (17.0) | 265 (29.2) | ||||

| Intermediate | 1056 (45.4) | 420 (46.3) | ||||

| High | 797 (34.2) | 165 (18.2) | ||||

| Unknown | 80 (3.4) | 57 (6.3) | ||||

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 4 (2.8) | 1395 (59.9) | ||||

| No | 139 (97.2) | 907 (39.0) | ||||

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 26 (1.1) | ||||

| Adjuvant endocrine therapy | .048 | .83 | ||||

| Yes | 22 (15.4) | 520 (22.3) | 21 (15.1) | 144 (15.9) | ||

| No | 120 (83.9) | 1780 (76.5) | 117 (84.2) | 759 (83.7) | ||

| Unknown | 1 (.7) | 28 (1.2) | 1 (.7) | 4 (.4) | ||

DCIS ductal carcinoma in situ

TABLE 2.

Ipsilateral breast events for patients with borderline lesions and DCIS, for the entire population and those not receiving adjuvant radiation

| Entire population (n = 2471)

|

No-radiation cohort (n = 1046)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borderline lesion | DCIS | Borderline lesion | DCIS | |

| N | 143 | 2328 | 139 | 907 |

| Follow-up (years), median | 2.9 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 5.1 |

| Ipsilateral breast event | ||||

| None | 136 | 2156 | 132 | 808 |

| Any | 7 | 172 | 7 | 99 |

| Invasive carcinoma | 5 | 73 | 5 | 42 |

| DCIS | 2 | 97 | 2 | 56 |

| Unknown type | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 year rate of ipsilateral breast event | 7.7 % | 7.2 % | 8.1 % | 10.7 % |

| 5 year rate of invasive ipsilateral breast cancer | 6.5 % | 2.8 % | 6.8 % | 4.2 % |

DCIS ductal carcinoma in situ

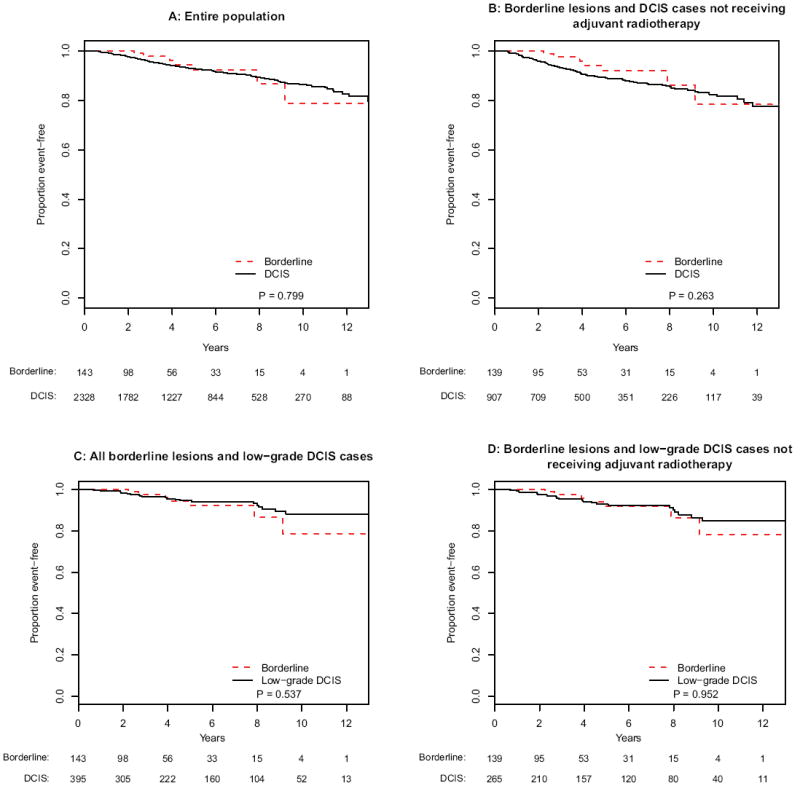

The 5 year rate of IBE was 7.7 % (95 % confidence interval [95 % CI], 1.0–14.3 %) for patients with borderline lesions and 7.2 % (95 % CI, 5.9–8.5 %) for those with DCIS (log-rank p = .80) (Fig. 1a). When the analysis was limited to patients who did not receive radiotherapy, there remained no significant difference in IBE between borderline-lesion patients and DCIS patients (5 year rates: 8.1 % [95 % CI, 1.1-15.1 %] and 10.7 % [95 % CI, 8.4 - 13.1 %], respectively) (Fig. 1b) (log-rank p = .26). When borderline-lesion patients and low-grade DCIS patients were compared, Kaplan–Meier curves overlap (p > .50) for both the entire population and the subset without radiation (Fig. 1c, d).

FIG. 1.

Kaplan-Meier analyses of ipsilateral breast events for patients with borderline lesions and DCIS for a the entire population, b borderline lesions and DCIS cases not receiving adjuvant radiotherapy, c borderline lesions and low-grade DCIS, and d borderline lesions and low-grade DCIS not receiving adjuvant radiotherapy

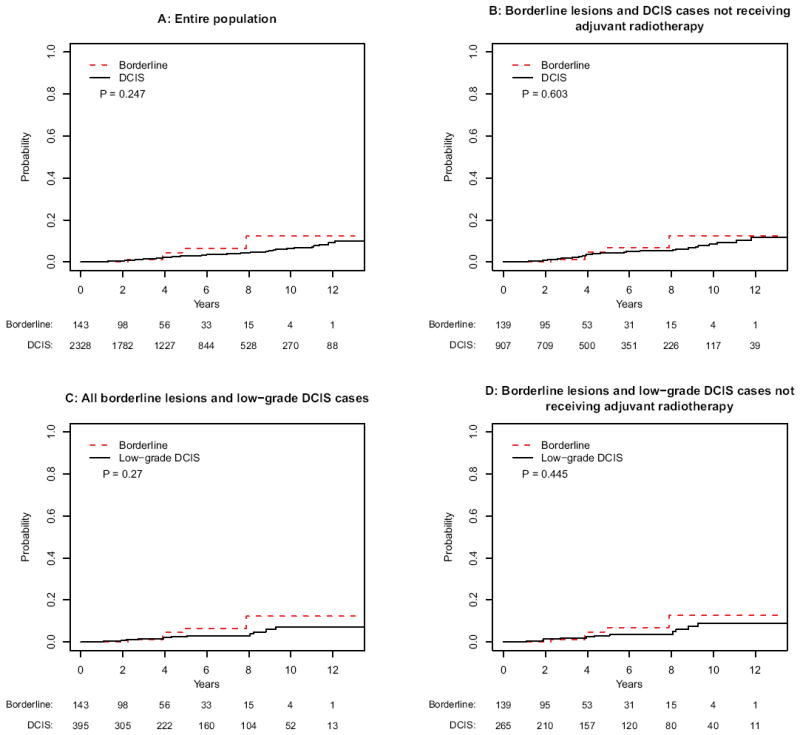

No significant differences in the incidences of invasive IBE were seen between patients with borderline lesions and DCIS, with 5 year invasive IBE rates of 6.5 and 2.8 %, respectively (p = .25) (Fig. 2a). Subset analyses of patients not receiving radiotherapy (p = .60) (Fig. 2b) and those with low-grade DCIS (p = .27 for all patients; p = .45 for no-radiotherapy cohort) (Fig. 2c, d) also showed no significant differences in invasive IBE rates between borderline lesions and DCIS.

FIG. 2.

Cumulative incidence analyses of invasive ipsilateral breast events for a the entire population, b borderline lesions and DCIS cases not receiving adjuvant radiotherapy, c borderline lesions and low-grade DCIS, and d borderline lesions and low-grade DCIS not receiving adjuvant radiotherapy

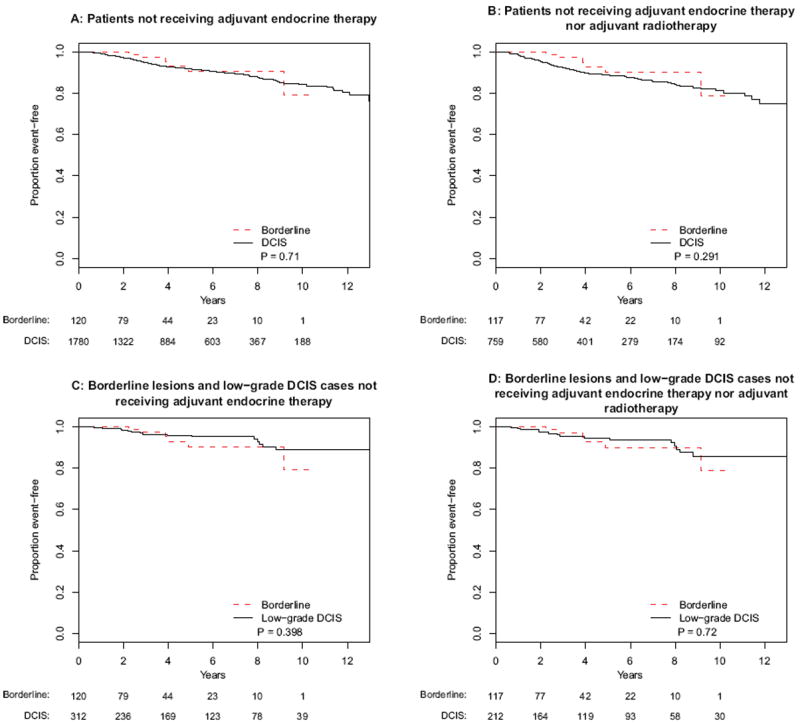

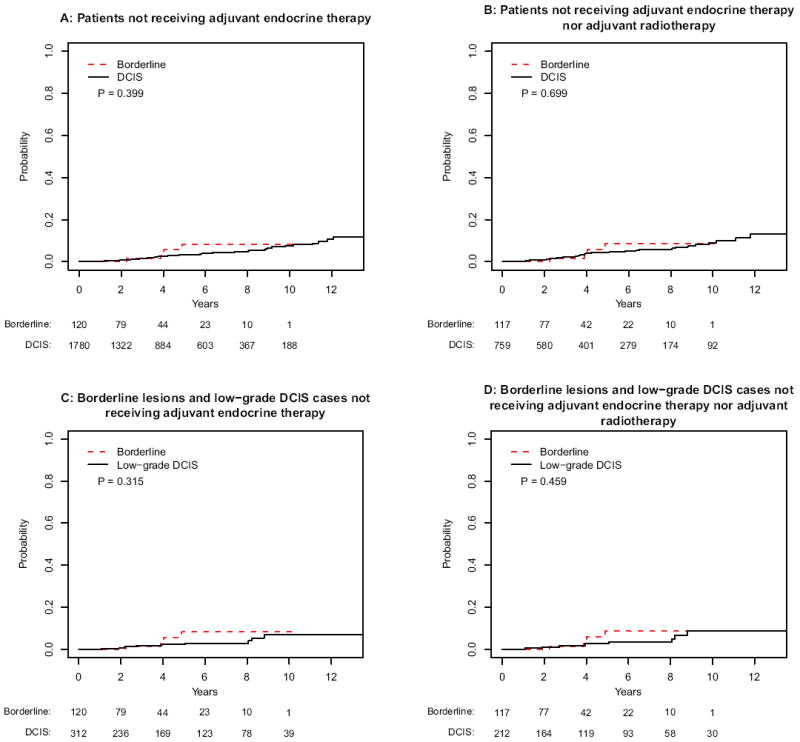

Although adjuvant endocrine therapy was routinely offered to both patients with borderline lesions and DCIS, fewer patients with borderline lesions received adjuvant endocrine therapy compared with DCIS (15.4 versus 22.4 %, respectively). Kaplan–Meier analyses were repeated for patients who did not receive adjuvant endocrine therapy. No statistically significant differences were detected for all IBE (borderline lesions versus DCIS [p = .71]; for borderline lesions versus low-grade DCIS [p = .40]) (Fig. 3a, c) or for invasive IBE (borderline lesions versus DCIS [p = .40]; for borderline lesions versus low-grade DCIS [p = .32]) (Fig. 4a, c).

FIG. 3.

Kaplan-Meier analyses of ipsilateral breast events for patients with borderline lesions and DCIS that did not receive endocrine therapy for a the entire population, b borderline lesions and DCIS cases not receiving adjuvant radiotherapy, c borderline lesions and low-grade DCIS, and d borderline lesions and low-grade DCIS not receiving adjuvant radiotherapy

FIG. 4.

Cumulative incidence analyses of invasive ipsilateral breast events for patients with borderline lesions and DCIS that did not receive endocrine therapy for a the entire population, b borderline lesions and DCIS cases not receiving adjuvant radiotherapy, c borderline lesions and low-grade DCIS, and d borderline lesions and low-grade DCIS not receiving adjuvant radiotherapy

Kaplan–Meier analyses were repeated for patients who received neither adjuvant radiotherapy nor adjuvant endocrine therapy. Again, no statistically significant differences were detected for all IBE (borderline lesions versus DCIS [p = .29]; for borderline lesions versus low-grade DCIS [p = .72]) (Fig. 3b, d) or for invasive IBE (borderline lesions versus DCIS [p = .70]; for borderline lesions versus low-grade DCIS [p = .46]) (Fig. 4b, d).

DISCUSSION

In a seminal analysis of 10,366 benign breast lesions in 3,303 women over a median follow-up of 17 years, Dupont et al. classified benign breast lesions into three categories based on varying risks for the development of subsequent invasive breast cancer: nonproliferative, proliferative lesions without atypia, and atypical hyperplasia (atypical ductal hyperplasia, atypical lobular hyperplasia).1,5,8-10

Over 15 years, 2 % of women with nonproliferative lesions, 4 % of women with proliferative lesions without atypia, 8 % of women with proliferative lesions with atypia and no family history, and 20 % of women with proliferative lesions with atypia and a family history developed a subsequent invasive breast cancer. More recent studies have demonstrated similar findings; in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) Prevention Trial (P-1), women with atypical hyperplasias had an initial 5 year observed invasive breast cancer rate of 5.0 %.11-13

This increased risk is not entirely surprising insofar as “atypical ductal hyperplasias are lesions that have some of the architectural and cytologic features of low-grade DCIS.”14 Indeed, Masood and Rosa summarize that “these morphologic and quantitative measures (which are used to distinguish ADH from DCIS) are quite subjective and somewhat arbitrary.”6

The quantitative measure currently used as a criteria for separation between ADH and low nuclear grade DCIS is “morphological changes of DCIS seen in <2 separate duct spaces or in <2 mm in maximum dimension.”6 One could hypothesize that perhaps the behavior of a lesion that is “borderline” only on the basis of small size may be different from one that is “borderline” on the basis of morphology. Future work should compare the outcomes based on morphologic and quantitative measures.

The blurriness of boundaries separating ADH and low-grade DCIS results in interobserver variation—what may be ADH to one pathologist may be low-grade DCIS to another. In a classic study, Rosai presented a series of cases of epithelial borderline lesions to 5 highly respected surgical pathologists.4 In none of the cases did all 5 pathologists agree on the histologic diagnoses, and in only 18 % of the cases did 4 out of 5 pathologists agree. Schnitt et al. found that when written standardized diagnostic criteria and teaching slides were given to pathologists, variations in diagnostic interpretations were reduced, but ubiquitous and unequivocal consensus was by no means achieved.15 They reported that 6 of 6 pathologists agreed on the diagnosis in only 58 % of cases. These findings suggest that some lesions are truly borderline and cannot be definitively categorized as ADH or as DCIS in spite of the use of standardized histologic criteria.

Unfortunately, current standards of practice do not allow for blurry boundaries—whereas ADH is considered a “risk factor” that warrants no specific therapeutic intervention, DCIS is considered a carcinoma in both nomenclature and practice. When confronted with a diagnosis of a borderline lesion, a clinician must counsel a patient regarding its significance and choose whether to pursue the less aggressive ADH treatment pathway (surveillance and consideration of risk-reducing endocrine therapy) or the more aggressive DCIS treatment pathway (excision to clear margins [or mastectomy] with consideration of therapeutic radiotherapy and endocrine therapy).

However, it is noteworthy that endocrine therapy may benefit both patient populations. NSABP P-1 demonstrated that for women with atypical hyperplasia, tamoxifen reduced annual invasive breast cancer rates from 1.04 to 0.26 %, a 75 % risk reduction.13 In NSABP B-24, in women who underwent lumpectomy and adjuvant radio-therapy for estrogen-receptor positive DCIS, the addition of tamoxifen reduced the risk of ipsilateral invasive breast carcinoma by 39 %.16 While the role of endocrine therapy for patients with borderline lesions has not been directly evaluated, these findings suggest that a significant risk reduction may be observed.

In this clinical audit, borderline lesions and DCIS did not behave differently. It is particularly noteworthy that analyses failed to demonstrate any differences in invasive IBE for borderline lesions versus DCIS (even when examining the subsets without adjuvant radiotherapy or endocrine therapy) and actually showed absolute rates of invasive carcinoma to be higher (not statistically significant) with borderline lesions (Fig. 2). Thus, it may be imprudent to consider borderline lesions as having lower malignant potential than DCIS. On the other hand, concerns about overdiagnosis and overtreatment of DCIS could also apply to “borderline” lesions if DCIS treatment options are offered to patients with such lesions.

There were too few patients with borderline lesions to perform a meaningful multivariable analysis. Nonetheless, the borderline-lesion and DCIS groups differed in regard to three clinicopathologic characteristics: age, menopausal status, and margin status. In our series, the borderline-lesion group was significantly younger than the DCIS group; median ages were 51 years of age versus 57 years of age, respectively (p < .001). It is well established that compared with older patients, younger patients have a higher risk of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence after treatment for DCIS.17-23 Another limitation of this series is the potential for selection bias resulting from inclusion of only women who underwent breast-conserving surgery. It is likely that larger and more aggressive DCIS lesions were more commonly treated with mastectomy than were “borderline” lesions. The greatest limitation of this report is the limited size and follow-up of our borderline-lesion population. Further studies of this population that include more patients and longer follow-up are needed. However, to our knowledge, this report constitutes the largest published series of patient outcomes for women with epithelial borderline lesions of the breast.

In summary, histologic studies support the existence of a neoplastic epithelial continuum and therefore the existence of borderline lesions. Clinically, borderline lesions and DCIS have similar subsequent rates of all IBE and, most importantly, of invasive IBE. Until biological markers are identified that can distinguish lesions with malignant potential from those without, caution should be used in treating borderline lesions. Knowledge of the similar magnitude of risk between borderline lesions and DCIS should be incorporated into risk estimation and patient management.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST None.

References

- 1.Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW, Rados MS. Atypical hyperplastic lesions of the female breast. A long-term follow-up study. Cancer. 1985;55:2698–708. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850601)55:11<2698::aid-cncr2820551127>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Page DL. Cancer risk assessment in benign breast biopsies. Hum Pathol. 1986;17:871–4. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(86)80636-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW. Ductal involvement by cells of atypical lobular hyperplasia in the breast: a long-term follow-up study of cancer risk. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:201–7. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(88)80350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosai J. Borderline epithelial lesions of the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:209–21. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199103000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page DL, Rogers LW. Combined histologic and cytologic criteria for the diagnosis of mammary atypical ductal hyperplasia. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:1095–7. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90026-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masood S, Rosa M. Borderline breast lesions: diagnostic challenges and clinical implications. Adv Anat Pathol. 2011;18:190–8. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31821698cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen PP. “Borderline” breast lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:1100–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupont WD, Page DL. Risk factors for breast cancer in women with proliferative breast disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:146–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dupont WD, Parl FF, Hartmann WH, Brinton LA, Winfield AC, Worrell JA, et al. Breast cancer risk associated with proliferative breast disease and atypical hyperplasia. Cancer. 1993;71:1258–65. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930215)71:4<1258::aid-cncr2820710415>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page DL, Dupont WD. Anatomic markers of human premalignancy and risk of breast cancer. Cancer. 1990;66:1326–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900915)66:14+<1326::aid-cncr2820661405>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, Lingle WL, Degnim AC, Ghosh K, et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:229–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall LM, Hunter DJ, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ, Byrne C, London SJ, et al. Risk of breast cancer associated with atypical hyperplasia of lobular and ductal types. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cecchini RS, Cronin WM, Robidoux A, et al. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: current status of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1652–62. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnitt SJ, Collins LC. Pathology of benign breast disorders. In: Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, Osborne CK, editors. Diseases of the Breast. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnitt SJ, Connolly JL, Tavassoli FA, Fechner RE, Kempson RL, Gelman R, et al. Interobserver reproducibility in the diagnosis of ductal proliferative breast lesions using standardized criteria. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:1133–43. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allred DC, Anderson SJ, Paik S, Wickerham DL, Nagtegaal ID, Swain SM, et al. Adjuvant tamoxifen reduces subsequent breast cancer in women with estrogen receptor-positive ductal carcinoma in situ: a study based on NSABP protocol B-24. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1268–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang ES, Samli B, Tran KN, Rosen PP, Borgen PI, Van Zee KJ. Volume of resection in patients treated with breast conservation for ductal carcinoma in situ. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;5:757–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02303488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Zee KJ, Liberman L, Samli B, Tran KN, McCormick B, Petrek JA, et al. Long term follow-up of women with ductal carcinoma in situ treated with breast-conserving surgery: the effect of age. Cancer. 1999;86:1757–67. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991101)86:9<1757::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bijker N, Meijnen P, Peterse JL, Bogaerts J, Van Hoorebeeck I, Julien JP, et al. Breast-conserving treatment with or without radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma-in situ: ten-year results of European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer randomized phase III trial 10853–a study by the EORTC Breast Cancer Cooperative Group and EORTC Radiotherapy Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3381–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes LL, Wang M, Page DL, Gray R, Solin LJ, Davidson NE, et al. Local excision alone without irradiation for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5319–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.8560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudloff U, Jacks LM, Goldberg JI, Wynveen CA, Brogi E, Patil S, et al. Nomogram for predicting the risk of local recurrence after breast-conserving surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3762–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho A, Goenka A, Ishill N, Van Zee K, McLane A, Gonzales AM, et al. The effect of age in the outcome and treatment of older women with ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast. 2011;20:71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ, Fisher B, Mamounas EP, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:478–88. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]