Short abstract

South Asian countries face similar health problems and would benefit from collaboration in health research

Research is essential to guide improvements in health systems and develop new initiatives.1 South Asia has a quarter of the world's population, weak public sector health care, and a staggering disease burden, and thus research is particularly important. Although investment has increased in infrastructure for health research over the past decade, gaps remain in evidence to guide reduction of important problems such as communicable diseases, maternal and perinatal conditions, childhood diseases, and nutritional deficiencies.2 Furthermore, even when technical knowledge is available, political commitment, managerial competencies, and incentives for changing behaviour within health systems are often lacking.3-5

One region, eight countries, complex challenges

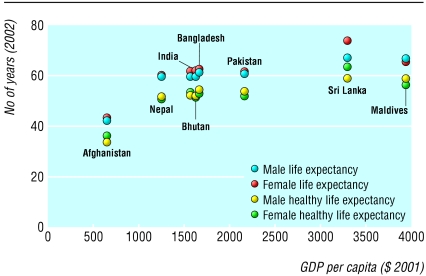

Despite diversity in their geographical, linguistic, and political structures, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka face common health challenges. Most bear a triple burden of persisting infectious diseases, increasing chronic conditions, and a growing recognition of injuries and violence. Incomplete demographic transitions, HIV and AIDS, massive unplanned urbanisation, and a host of social determinants of health compound these problems.6 Another common characteristic is that national estimates of health mask large variations within countries (fig 1).7,8

Fig 1.

Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy by gross domestic product per capita9

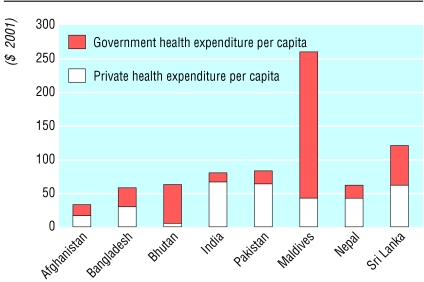

Health systems across the region also have to confront challenges such as a lack of evidence based policies and limited social accountability. With no or limited national health insurance schemes and the large role of the private sector, individuals face high out of pocket payments on top of other economic and social consequences of ill health (fig 2).10 In many countries, the devolution of financial responsibility for health services has outpaced capacity and decision making authority, contributing to fragmentation of policies and services.11 Striking inequities in the provision of human resources, infrastructure, and effective services abound between regions of countries, socioeconomic classes, and rural and urban areas.8

Fig 2.

Government and private expenditure on health per capita9

Health research and health system challenges

A systems perspective12 is required to understand how research and knowledge from various sources is produced and synthesised, how the demand for relevant knowledge is cultivated, and whether that knowledge is used to strengthen the effectiveness of health systems, improve health, and reduce inequities. This perspective forms the concept of a health research system.13 Such systems have four basic components: stewardship, financing, human and institutional capacity, and producing and using research. We examine the state of these functions across South Asia.

Stewardship

The competing goals and fragmentation of research are evident across the region. Debates about the appropriate balance between research driven by investigators or funders and that driven by policy and specific problems assume that a vision and mechanism exist to oversee, coordinate, and implement a consensus. Medical research councils in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan have held this role for some time, historically focusing on traditional, public financed medical research. Other countries have set up coordinating bodies more recently (table 1). Most countries now have formal national health policies that include, to varying degrees, research priorities (see bmj.com).

Table 1.

National medical or health research coordination bodies

| Country | Body | Year established |

|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | Bangladesh Medical Research Council | 1972 |

| Bhutan | Health Research and Epidemiology Unit, Ministry of Health and Education | 1995 |

| India | Indian Council for Medical Research | 1911 |

| Pakistan | Pakistan Medical Research Council | 1962 |

| Maldives | Health Information and Research Unit, Ministry of Health | 1998 |

| Nepal | Nepal Health Research Council | 1991 |

| Sri Lanka | National Health Research Council | 1996 |

The effectiveness of these bodies is often hampered by bureaucratic hurdles and limited funds. Ideally, governments would have a coordinating role in partnership with other stakeholders from civil society, science and technology, education, and other health related areas in the public and private sectors. This should ensure the development of health research policies that reflect the priorities of the country; creation of an enabling environment to foster appropriate health research; evaluation of cost effectiveness of research; and development of rules to resolve ethical issues concerning the process and benefits of research.

Financing

The Global Forum for Health Research emphasised the need to strengthen research capacity in developing countries to redress the “10/90” gap—that only 10% of all global health research funding was allocated to 90% of the world's burden of preventable mortality.14 In many countries, such as Nepal and Bangladesh, inadequate funding is the main barrier to health research. Despite the enormous disease burden in South Asia, research is often viewed as an expenditure rather than an investment. Moreover, case studies from Nepal, Bangladesh, and Pakistan report that the bulk of government funding for research goes towards training, salaries, and infrastructure, resulting in research projects being largely funded (and influenced) by external donors.

Financial and technical support from external partners has been crucial. Nevertheless, past experiences indicate that for the long term development and sustainability of national health research, a holistic perspective is needed to develop options for sustainable public financing, pooling of donors' contributions, more transparent allocation of funds, and the alignment of research funding with research priorities. Additionally, as the case of Pakistan shows, improvements in the amount and allocation of funding are not sufficient. Although about $1.5m (£826 000, €1.2m) was available to the Pakistan Medical Research Council between 1994 and 2000, less than half of that amount was disbursed because of a lack of good proposals.

It is difficult, however, to estimate the amount currently spent on health research for the whole region and whether this funding is appropriately targeted at national health priorities. No country in the region has complete accounting of sources of funds and allocation to research topics. Current guidelines for national health accounts include expenditures for only selected types of research and development in health, and almost no countries currently report these “health related” expenses.15 That one of the 14 goals of India's national health policy is to establish an integrated system of surveillance, national health accounts, and health statistics by 2005, indicates awareness of the need to strengthen national and subnational capacities urgently.16

Human and institutional capacity

What skills and perspectives should be nurtured in individuals and institutions? A recent report on South Asia identified health financing, provider payments mechanisms, organisation of services, state regulation, and behaviour of the public and healthcare providers as priority research topics.17 A people centred approach evokes additional crosscutting research themes, such as equity, better use of existing knowledge, and engagement of society. Yet medical and health research councils across the region lament the lack of expertise in ethical review, health economics, epidemiology, anthropology, and health policy and the shortage of staff with statistical, analytical, and managerial skills. This severely limits the ability to formulate research proposals or oversee complex research projects.3,4 These skills are also relevant to functions that need to be upgraded within the region's health systems—for example, disease surveillance, health and management information systems, quality assurance, or vital registration systems.

However, attracting and retaining researchers within academic institutions and professionals within the health system requires coordinated strategies that are not restricted to the health sector. The flow of trained staff from South Asia to high income countries, as well as between countries in the region, is an important phenomenon. A survey of people from Pakistan sent abroad for doctoral training on public grants documented numerous factors influencing their return, stay, and productivity in the country.18 The researchers cited lack of academic liberty, absence of professional incentives, poor funding, and unclear career pathways among the reasons for suboptimal performance.

Development of health research capacity also requires a focus on institutions. The quality of facilities, communication and information technologies, and approaches to get research findings to target audiences vary tremendously.3-5 Until recently, most health researchers in Nepal worked individually rather than based within institutions, whereas in Afghanistan, nongovernmental organisations—often with expatriates as principal investigators—have sponsored the bulk of research, particularly on infectious diseases and basic provision of services. In Bangladesh, indigenous non-governmental organisations such as the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee have contributed to health systems research (see bmj.com). Public-private partnerships are also steadily increasing, most notably between the pharmaceutical industry and related research institutes in India, and should be encouraged to develop drugs for neglected diseases, not only generic drugs.3

Given this context, what options exist for the region? One strategy is to intensify collaboration and conduct multisite studies. Despite common challenges, borders, and languages, data from publications show limited collaboration within countries or across countries in South Asia (table 2). For example, of 73 articles on health research topics with an author's address in Sri Lanka, only nine have at least one author with an address in another country in the region, while 21 articles have only one institutional address.

Table 2.

Collaboration patterns on health research topics within South Asia, based on copublications in 2001*

|

Collaboration

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Bangladesh | India | Pakistan | Maldives | Nepal | Sri Lanka | Intraregional | Inter-regional | None | Total† |

| Bangladesh | 11 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 76 | 42 | 142 |

| India | 10 | 1187 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 24 | 632 | 2307 | 4150 |

| Pakistan | 1 | 4 | 15 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 77 | 67 | 167 |

| Maldives | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Nepal | 1 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 43 | 9 | 64 |

| Sri Lanka | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 9 | 35 | 21 | 73 |

Restricted to countries in South Asia with at least one journal article with an address in that country and included within health related journals published in 2001 included within the ISI database. Country attribution based on all authors' addresses as noted within the ISI database.19

Sum of internal, intraregional, inter-regional, and no collaboration.

Producing and using research

More generally, research articles by health researchers in South Asia comprised 1.2% of all annual research on health topics within the Institute for Scientific Information's database from 1992 to 2001. This relatively low proportion indicates how little is shared, rather than how much research is done in the region. For example, preliminary data based on interviews with 190 Pakistani health researchers documents a wide range of research outputs between 1998 and 2002: peer reviewed journal articles referenced in international databases make up about 15% of all outputs; articles referenced in regional or national databases about 25%; conference presentations almost 30%; and patents, books, and unpublished manuscripts about 15%. Outputs that target non-researchers, such as policy reports, press releases, and other media items make up the remaining 15%.

Figure 3.

Oral rehydration therapy, an evidence based intervention

Credit: AP PHOTO/PAVEL RAHMAN

Producing research does not guarantee that it is used. Efforts to increase the accessibility of research, such as regional databases20 or the Health InterNetwork Access to Research Initiative (HINARI),21 are welcome. Through HINARI, selected public health related institutions in Bhutan and Nepal receive free electronic access to over 1500 major international journals, and some institutions in the Maldives have access at discounted prices. Are these activities making a difference? Dr U Than Sein, the director within WHO's South East Asian Regional Office responsible for health systems, told us that increasing access in the region is viewed primarily as a “technology” issue, and even then, one that is far from being fulfilled. “Once access is increased dramatically,” he noted, “then countries may be able to address the more critical question of how to transform and use knowledge to improve health services or health status”

Strategies to increase research must develop alongside steps to stimulate policymakers and practitioners to demand and use research evidence.22 Bhutan, the Maldives, and Sri Lanka have established units within their ministries of health to help connect health research with the health system. This is a positive step, but the challenges are complex and require long term commitments. A recent case study on the Maldives notes that although demand for research is growing, some 65% of health sector staff find research reports difficult to interpret.3 Nevertheless, examples of successful implementation of health systems research exist, such as use of oral rehydration therapy in Bangladesh and treatment of thalassaemia in the Maldives.23

Summary points

Solutions to the challenges faced by South Asia's health systems challenges need to be refined and tested within the region

Health research should be organised from a systems perspective with an emphasis on ethics and equity

An enabling environment for research requires vision, institutional support, adequate funds, appropriate training, and attractive career pathways

Collaboration across the region needs to be strengthened

Use of health research to inform health policy, professional practices, and public behaviour needs to be increased

Need for collaboration

Encouraging collaboration across the region and beyond is not at odds with supporting the development of national health systems. Region specific strains of diseases, common environmental threats, and topics neglected from the perspective of research priorities of high income countries, provide sufficient ground for regional cooperation. Steps are already being taken to encourage cooperation (see below) and these need to be built on.

Facilitate discussions and sharing of national and subnational experiences—For example, a WHO sponsored meeting in August 2003 brought together scientists from seven South Asian countries, particularly enabling Indian and Pakistani health researchers to mix. A concrete plan for collaboration emerged, including developing joint projects and common research protocols in maternal and child health, infectious disease control, genomics, and ethics.24

Support cross border training—Many opportunities exist, such as research training offered at the Bangladesh Institute of Research and Rehabilitation in Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. This institute offers training on service provision guidelines and evaluating the cost effectiveness of interventions, as well as basic research.

Develop networks of researchers, policymakers, and institutions—The transformation of networks of individuals into formal collaborations based on institutional commitments across Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan is another trend that should be encouraged. The Asian Forum for Health Research (established in 2000) evolved into the Asia-Pacific Forum for Health Research and, since December 2003, includes a South Asian caucus. These networks should be extended to include health professionals and decision makers. Moreover, the creation of an umbrella organisation like the European Observatory on Health Care Systems25 to share regional experiences concerning key health systems reforms directly with policy-makers and civil society representatives will increase the likelihood that research and knowledge effectively shape the development of health systems.

Increase political visibility of health and development—Stability in the region is essential for regional cooperation. At the 12th South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation summit of regional leaders in January 2004, governments drafted a new social charter that notes “the promotion of health as a regional objective.”26 Governments agreed to share information, provide training to professionals in public health and curative skills in response to communicable disease outbreaks, and adopt a coordinated approach to health related issues in international forums. Strategies are now needed to translate political will into actions that improve people's lives.

Supplementary Material

Extra information is available on bmj.com

Extra information is available on bmj.com

We thank Guillermo Paraje and Ghassan Karam for the analyses on copublication patterns in the region as well as Shook-Pui Lee-Martin, Lalit Kant, Tasleem Akhtar, Liaquat Ali, U Than Sein, Mohamed Abdur Rab, Sylvia de Haan, and Adik Wibowo.

Contributors and sources: RS has been involved in health systems issues since 1983, with special interest in health policy formulation, non-fatal health, and reproductive health capacity strengthening, and currently leads the Health Research Systems Analysis initiative within WHO, Geneva. CD has studied development economics and has a special interest in issues related to health research policy and priority setting in developing countries. AH has been involved in health systems development and research for the past 15 years in South Asia with special interest in burden of disease assessment, injuries, and equity issues and is special advisor to the Pakistan Medical Research Council. MC has been involved in health research and programme evaluations in Bangladesh and other South Asian countries, including Pakistan and Nepal. The multidisciplinary research programs of BRAC in Bangladesh developed under his leadership over the past two decades. This paper drew on case studies on health research systems in South Asian countries sponsored by the Council on Health Research for Development and WHO, other grey literature, peer reviewed literature, conference discussions, and interviews during the Global Forum for Health Research 2003 and the Global Development Network Conference 2004, and new analytical work sponsored by the Health Research Systems Analysis Initiative.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Commission on Health Research for Development. Health research: essential link to equity in development. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- 2.Bhutta ZA. Why has so little changed in maternal and child health in South Asia? BMJ 2000;321: 809-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO South-East Asia Regional Office. Review of national health research systems: Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Sri Lanka. Background documents for the 27th Session of WHO South-East Asia Advisory Committee on Health Research, 15-18 April 2002, Dhaka.

- 4.Akhtar T, Khan J. Health research capacity in Pakistan. Pakistan: Council on Health Research for Development, 2000.

- 5.Hossain M. Essential national health research in Bangladesh: an ENHR country monograph. Geneva: Council on Health Research for Development, 2000.

- 6.Islam A, Tahir MZ. Health sector reform in South Asia: new challenges and constraints. Health Policy 2002;60: 151-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pappas G, Akhter T, Gergen PJ, Hadden WC, Khan AQ. Health status of the Pakistani population: a health profile and comparison with the United States. Am J Public Health 2001;91: 93-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bangladesh Health Equity Watch. Brochure, Dhaka 2002. www.gega.org.za/download/newsvol1_6/bhewbrochure.pdf (accessed 19 Mar 2004).

- 9.World Health Organization. World Health Report 2003: shaping the future. Geneva: WHO, 2003.

- 10.Ray TK, Pandav CS, Anand K, Kapoor SK, Dwivedi SN. Out-of-pocket expenditure on healthcare in a north Indian village. Natl Med J India 2002;15: 257-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters DH, Rao KS, Fryatt R. Lumping and splitting: the health policy agenda in India. Health Policy Plann 2003;18: 249-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Report of the international conference on health research for development, Bangkok, 10-13 October. Lausanne: International Organizing Committee, 2001.

- 13.Pang T, Sadana R, Hanney S, Bhutta ZA, Hyder AA, Simon J. Knowledge for better health - a conceptual framework and foundation for health research systems. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81: 777-854. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Global Forum for Health Research. The 10/90 report on health research. Geneva: GFHR, 1999.

- 15.World Health Organization. Guide to producing National Health Accounts with special applications for low-income and middle-income countries. Geneva: WHO, 2003:tables 3.1, 3.2.

- 16.Agarwal SP. National health policy 2002: new perspectives. Natl Med J India 2002;15: 213-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters DA, Yazbeck AS. A Framework for Health Policy Research in South Asia. In: Human Development Network. Health Policy Research in South Asia: building capacity for reform. Washington DC: World Bank, 2004.

- 18.Hyder AA, Akhter A, Qayyum A. Evaluating capacity development for health research in Pakistan: case study on doctoral training. Health Policy Plann 2003;18: 338-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paraje G, Karam G, Sadana R. Methodological caveats to producing bibliometric indicators for health topics. Geneva: WHO, in press. (Research policy and cooperation discussion paper.)

- 20.World Health Organization. National Library of Medicine regional databases. www.who.int/library/country/regional/index.en.shtml (accessed 18 Mar 2004).

- 21.Health InterNetwork Access to Research Initiative. Scientific publications. www.healthinternetwork.org (accessed 18 Mar 2004).

- 22.Innvaer S, Vist G, Trommald M, Oxman A. Health policy-makers' perceptions of their use of evidence: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy 2002;7: 239-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministry of Communication, Science and Technology, WHO South-East Asia Advisory Committee on Health Research. Report to the regional director. New Delhi: WHO SEARO, 2003.

- 24.World Health Organization. Health research systems development in the WHO South-East Asia and Eastern Mediterranean regions: report of a bi-regional meeting, Maldives, 13-14 August 2003. Geneva: WHO, 2003.

- 25.European Observatory on Health Care Systems. www.euro.who.int/observatory (accessed 18 Mar 2004).

- 26.Federal Bureau Report. SAARC leaders signs accord on social charter. Pakistan Times pakistantimes.net/2004/01/05/top1.htm (accessed 6 Jan 2004).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.