Abstract

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is an autosomal dominant heart disease mostly due to mutations in genes encoding sarcomeric proteins. HCM is characterised by asymmetric hypertrophy of the left ventricle (LV) in the absence of another cardiac or systemic disease. At present it lacks specific treatment to prevent or reverse cardiac dysfunction and hypertrophy in mutation carriers and HCM patients. Previous studies have indicated that sarcomere mutations increase energetic costs of cardiac contraction and cause myocardial dysfunction and hypertrophy. By using a translational approach, we aim to determine to what extent disturbances of myocardial energy metabolism underlie disease progression in HCM.

Methods

Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) patients and aortic valve stenosis (AVS) patients will undergo a positron emission tomography (PET) with acetate and cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) with tissue tagging before and 4 months after myectomy surgery or aortic valve replacement + septal biopsy. Myectomy tissue or septal biopsy will be used to determine efficiency of sarcomere contraction in-vitro, and results will be compared with in-vivo cardiac performance. Healthy subjects and non-hypertrophic HCM mutation carriers will serve as a control group.

Endpoints

Our study will reveal whether perturbations in cardiac energetics deteriorate during disease progression in HCM and whether these changes are attributed to cardiac remodelling or the presence of a sarcomere mutation per se. In-vitro studies in hypertrophied cardiac muscle from HOCM and AVS patients will establish whether sarcomere mutations increase ATP consumption of sarcomeres in human myocardium. Our follow-up imaging study in HOCM and AVS patients will reveal whether impaired cardiac energetics are restored by cardiac surgery.

Keywords: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Carrier, Myocardial energetics, Sarcomere mutations

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a common genetic cardiac disease with an estimated prevalence of 1:500 in the general population. HCM is most frequently caused by mutations in genes encoding sarcomeric proteins and is characterised by asymmetric remodelling of the left ventricle (LV) in the absence of increased loading conditions or (infiltrative) systemic disease likely to cause hypertrophy [1]. The phenotypic expression has intrafamilial and interfamilial variability, ranging from no or mild symptoms throughout life to the occurrence of progressive heart failure or sudden cardiac death at young age. Apart from surgical removal of septal myocardium in patients with symptomatic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, no treatment to prevent or reverse cardiac dysfunction and development of hypertrophy exists, as the exact mechanisms by which mutations cause LV dysfunction and hypertrophy are still incompletely resolved.

Sarcomere contractility

Initially, it was proposed that sarcomere gene mutations would depress myocardial contractility leading to compensatory hypertrophy by activation of neuroendocrine and mechanical responses [2]. Low force generating capacity by sarcomeres has been found in single cardiomyocytes isolated from patients with obstructive HCM (HOCM) [3–7]. The low cardiomyocyte force development in HCM patients was largely explained by hypertrophy and reduced myofibrillar density in HCM with mutations in genes encoding cardiac myosin-binding protein-C and thin filament proteins [7]. In addition, some specific missense mutations, in particular in the gene encoding the thick filament protein myosin heavy chain, lower the intrinsic force generating capacity of sarcomeres, possibly by changing cross-bridge turnover kinetics [7, 8]. Opposite to low maximal force generating capacity, both in-vitro and in-vivo studies using various recombinant proteins and transgenic mice models observed increased Ca2+ sensitivity of the myofilaments indicative for a mutation-induced increase in contractility at submaximal Ca2+ concentrations [9, 10]. Our recent studies in samples from HOCM patients indicated that high myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity is indeed a common characteristic of human HCM, though can be partly explained by altered phosphorylation of sarcomeres rather than the mutation itself [5, 7, 11]. In addition, missense mutations perturb length-dependent activation of sarcomeres evident from a blunted increase in force development upon an increase in sarcomere length [11]. Overall, the effect of an HCM mutation on contractile performance of the sarcomeres is determined by which sarcomeric gene is affected, the location of the mutation within the gene (and protein) and dose of the mutant protein ultimately resulting from the genetic mutation.

Energetics of cardiac contraction

Apart from perturbed contractility, cardiac performance may be impaired by altered energetics of the myocardium. The energy homeostasis may be affected by the HCM mutation through the following mechanism: both impaired and increased contractility (at physiological Ca2+ concentrations) may lead to increased ATP utilisation of the sarcomeres and a relative depletion of energy storage. A mismatch between energy supply and demand is thought to initiate a self-perpetuating cycle in which other ATP consuming mechanisms in cardiomyocytes, such as re-uptake of Ca2+ by the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase pump, will prolong cytosolic Ca2+ transients and stimulate Ca2+ dependent hypertrophic signalling pathways [12], rendering the myocardium less efficient in patients with HCM mutations. Indeed, several studies in transgenic mice harbouring mutations in genes encoding myosin heavy chain [13] and the thin filament protein troponin T [14, 15] suggested increased ATP utilisation by the sarcomeres. In humans, indirect evidence of increased ATP consumption has been obtained using cardiac imaging studies. With magnetic resonance spectroscopy, it has been shown that cardiac phosphocreatine (PCr) to ATP ratio, an indirect measure of energy status, is reduced by 30 % in HCM patients compared with controls, irrespective of the extent of hypertrophy [16, 17]. This suggests that energy deficiency is a primary event rather than a secondary consequence of left ventricular remodelling. This is supported by results from a pharmacological intervention study in HCM patients using perhexiline, a modulator of substrate metabolism, shifting metabolism from free fatty acids to the more efficient glucose. After 4.6 ± 1.8 months of perhexiline treatment, improved diastolic function and increased exercise capacity were observed in HCM patients treated with perhexiline [18]. However, the positive effects of perhexiline may also be explained by improvement of myocardial perfusion. Moreover, direct evidence of increased ATP utilisation for sarcomere contraction in human HCM is lacking. Therefore, the assumption that increased ATP consumption of affected sarcomeres plays an important role in the development of HCM is still debatable. By using a translational approach, within the ENGINE study (ENerGetIcs in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: traNslation between MRI, PET and cardiac myofilament function), we aim to determine to what extent disturbances of myocardial energy metabolism underlie disease progression in HCM.

Materials & methods

Study population

To investigate whether changes in myocardial energy metabolism depend on the presence of a sarcomere mutation and/or are explained by hypertrophic remodelling of the heart, a comparison is made between four groups. Firstly, HCM mutation carriers without evident LV hypertrophy are compared with manifest HCM patients with LV outflow tract obstruction (HOCM) to assess the progress of changes in cardiac energetics during HCM disease development. These groups are compared with a healthy control group and patients with acquired LV remodelling due to aortic valve stenosis (AVS). The latter group will reveal to what extent LV remodelling underlies changes in cardiac energetics.

Exclusion criteria includes (previously documented) coronary artery disease; previous septal reduction therapy; poor left ventricular function (ejection fraction <50 %); a history of diabetes mellitus or hypertension (defined as a blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg); contraindications to magnetic resonance imaging, including pacemaker and defibrillator implantation; severe claustrophobia and significant renal dysfunction (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 ml/min/1.73 m2).

The Medical Ethics Review Committee of the participating hospitals (VU University Medical Center (VUmc) in Amsterdam; Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis (OLVG) in Amsterdam; St. Antonius Hospital (AZN) in Nieuwegein and University Medical Center (UMCU) in Utrecht) approved the study. Informed consent will be obtained from all participants.

Study design

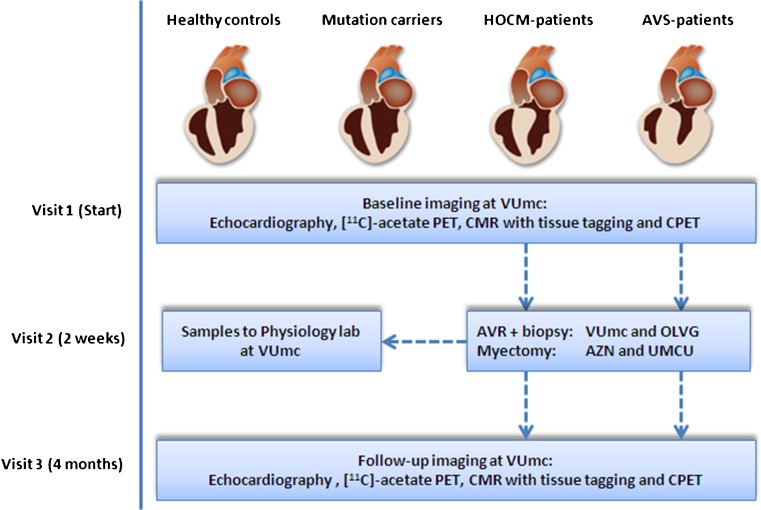

HOCM patients (maximum LV wall thickness ≥13 mm in the absence of other cardiac or systemic causes of LV hypertrophy) and AVS patients will undergo a transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), positron emission tomography (PET) with acetate, cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) with tissue tagging and a cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) before and 4 months after myectomy surgery or aortic valve replacement (Fig. 1). In-vitro measurements of sarcomere ATP consumption for force development will be performed in cardiac samples from HOCM patients obtained during surgical myectomy and from AVS patients with concentric hypertrophy during valve replacement (peak transvalvular gradient of >50 mmHg, no more than minimal aortic regurgitation (grade ≤1). In-vitro results will be correlated with in-vivo cardiac performance. The healthy control group and non-hypertrophic carriers with normal LV geometry will only undergo baseline in-vivo measurements.

Fig. 1.

ENGINE study design: translational, prospective, multicentre study. PET, positron emission tomography; CMR, cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise test; AVR, aortic valve replacement

Transthoracic echocardiography

Echocardiography will be performed according to the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines. LV dimensions will be measured at end diastole by 2D guided M-mode echocardiography. Continuous wave Doppler will be used to derive LV outflow tract gradient and peak transvalvular pressure gradient across the aortic valve. To assess diastolic LV function, pulsed-wave Doppler transmitral inflow will be obtained from the apical 4-chamber view.

Positron emission tomography

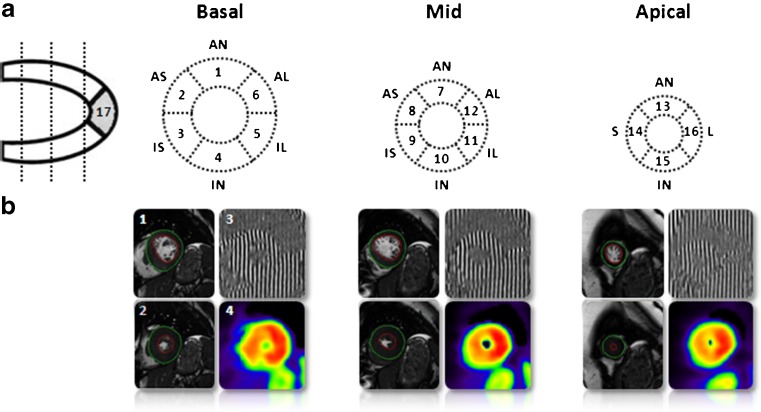

Before PET acquisition, venous blood will be drawn and metabolic parameters such as NH2-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), haemoglobin (Hb), creatinine, free fatty acids (FFA), glucose, and lactate levels will be determined. Subsequently, patients will undergo a [11C]-acetate PET study to quantitatively evaluate regional oxygen consumption according to the 17-segment model of the American Heart Association [19] (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

The measurement of segmental myocardial efficiency. a. 17-segment model according to the consensus of the American Heart Association. Left ventricular short-axis slices with location of the slices and the names of the segments. AN=anterior, AS=anteroseptum, IS=inferoseptum, IN=inferior, IL=inferolateral, AL=anterolateral, S=septal, L=lateral. b. Left ventricular short-axis cine images in 1. end-diastolic (ED) and 2. end-systolic (ES) phase. 3. CMR tissue tagging image with vertical taglines and 4. Parametric image of [11C]-acetate washout as obtained after kinetic analysis

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging

LV volume analysis will be performed by manually drawing epicardial and endocardial contours on all end-diastolic (ED) and end-systolic (ES) LV short-axis cine images (Fig. 2b). Global LV function parameters will be determined: LVED volume (LVEDV), LVES volume (LVESV), LV ejection fraction (LVEF), and LV myocardial mass. CMR tissue tagging images will be used to quantify regional intramyocardial deformation, allowing to measure segmental peak systolic circumferential strain and diastolic circumferential strain rate. Finally, each myocardial segment will be evaluated for the presence of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE). The combination of CMR and PET imaging will allow detailed, non-invasive measurement of myocardial efficiency [20].

Cardiopulmonary exercise test

Cyclo-ergometry exercise will be performed using a ramp protocol of 10–20 watts per min. Individuals will cycle until they reach the point of exhaustion or symptom limitation. Breath-by-breath gas exchange analysis will be performed. Respiratory gases will be sampled continuously via a mouthpiece and analysed for oxygen and an infrared sensor for carbon dioxide. Using this method, peak oxygen consumption (peak VO2), defined as the highest VO2 achieved during exercise, can be determined before and after surgery.

In-vitro measurements

ATP consumption, i.e. ATPase activity, will be measured using an enzyme-coupled assay in membrane-permeabilised multicellular muscle strips as described previously [21]. The economy of muscle contraction is expressed as tension cost (TC), i.e. the amount of ATP used during the development of maximum force (ATPase activity/Tension generation).

Study endpoints

Our study will reveal whether perturbations in cardiac energetics deteriorate during disease progression in HCM and whether these changes are attributed to cardiac remodelling or the presence of a sarcomere mutation per se. In vitro studies in hypertrophied cardiac muscle from HOCM and AVS patients will establish whether sarcomere mutations increase ATP consumption of sarcomeres in human myocardium. Our follow-up imaging study in HOCM and AVS patients will reveal whether impaired cardiac energetics are restored by cardiac surgery.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the 7th Framework Program of the European Union (‘BIG-HEART’ grant agreement 241577), from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO; VIDI grant) and Netherlands Heart Foundation (‘Dekker Grant’ grant agreement 2011T33)

Disclosures

None

Contributor Information

A. Güçlü, Phone: +31-20-4443847, FAX: +31-20-4443395, Email: a.guclu@vumc.nl

T. Germans, Phone: +31-20-4442244

E. R. Witjas-Paalberends, Phone: +31-20-4448110

G. J. M. Stienen, Phone: +31-20-4448110

W. P. Brouwer, Phone: +31-20-4442244

H. J. Harms, Phone: +31-20-4442234

J. T. Marcus, Phone: +31-20-4442244

A. B. A. Vonk, Phone: +31-20-4444515

W. Stooker, Phone: +31-20-5993032

A. Yilmaz, Phone: +31-30-6092045

P. Klein, Phone: +31-30-6092045

J. M. ten Berg, Phone: +31-30-6092045

J. Kluin, Phone: +31-88-7564823

F. W. Asselbergs, Phone: +31-88-7564823

A. A. Lammertsma, Phone: +31-20-4442234

P. Knaapen, Phone: +31-20-4442244

A. C. van Rossum, Phone: +31-20-4442244

J. van der Velden, Phone: +31-20-4448110

References

- 1.Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;287:1308–1320. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marian AJ. Pathogenesis of diverse clinical and pathological phenotypes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2000;355:58–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoskins AC, Jacques A, Bardswell SC, et al. Normal passive viscoelasticity but abnormal myofibrillar force generation in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraft T, Witjas-Paalberends ER, Boontje NM, et al. Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: functional effects of myosin mutation R723G in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;57:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Dijk SJ, Dooijes D, dos Remedios CG, et al. Cardiac myosin-binding protein C mutations and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: haploinsufficiency, deranged phosphorylation, and cardiomyocyte dysfunction. Circulation. 2009;119:1473–1483. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.838672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Dijk SJ, Paalberends ER, Najafi A, et al. Contractile dysfunction irrespective of the mutant protein in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with normal systolic function. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:36–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witjas-Paalberends ER, Piroddi N, Stam K, et al. Mutations in MYH7 reduce the force generating capacity of sarcomeres in human familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99:432–441. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belus A, Piroddi N, Scellini B, et al. The familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-associated myosin mutation R403Q accelerates tension generation and relaxation of human cardiac myofibrils. J Physiol. 2008;586:3639–3644. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.155952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elliott K, Watkins H, Redwood CS. Altered regulatory properties of human cardiac troponin I mutants that cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22069–22074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002502200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho CY, Sweitzer NK, McDonough B, et al. Assessment of diastolic function with Doppler tissue imaging to predict genotype in preclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2002;105:2992–2997. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000019070.70491.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sequeira V, Wijnker PJ, Nijenkamp LL, et al. Perturbed length-dependent activation in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with missense sarcomeric gene mutations. Circ Res. 2013;112:1491–1505. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashrafian H, Redwood C, Blair E. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy:a paradigm for myocardial energy depletion. Trends Genet. 2003;19:263–268. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spindler M, Saupe KW, Christe ME, et al. Diastolic dysfunction and altered energetics in the alphaMHC403/+ mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1775–1783. doi: 10.1172/JCI1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Javadpour MM, Tardiff JC, Pinz I, et al. Decreased energetics in murine hearts bearing the R92Q mutation in cardiac troponin T. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:768–775. doi: 10.1172/JCI15967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montgomery DE, Tardiff JC, Chandra M. Cardiac troponin T mutations: correlation between the type of mutation and the nature of myofilament dysfunction in transgenic mice. J Physiol. 2001;536:583–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0583c.xd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crilley JG, Boehm EA, Blair E, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy due to sarcomeric gene mutations is characterized by impaired energy metabolism irrespective of the degree of hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1776–1782. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)03009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timmer SA, Germans T, Brouwer WP, et al. Carriers of the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy MYBPC3 mutation are characterized by reduced myocardial efficiency in the absence of hypertrophy and microvascular dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1283–1289. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abozguia K, Elliott P, McKenna W, et al. Metabolic modulator perhexiline corrects energy deficiency and improves exercise capacity in symptomatic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2010;122:1562–1569. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.934059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, et al. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2002;18:539–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knaapen P, Germans T, Knuuti J, et al. Myocardial energetics and efficiency: current status of the noninvasive approach. Circulation. 2007;115:918–927. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.660639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narolska NA, van Loon RB, Boontje NM, et al. Myocardial contraction is 5-fold more economical in ventricular than in atrial human tissue. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]