Abstract

ANG II is the most potent and important member of the classical renin-angiotensin system (RAS). ANG II, once considered to be an endocrine hormone, is now increasingly recognized to also play novel and important paracrine (cell-to-cell) and intracrine (intracellular) roles in cardiovascular and renal physiology and blood pressure regulation. Although an intracrine role of ANG II remains an issue of continuous debates and requires further confirmation, a great deal of research has recently been devoted to uncover the novel actions and elucidate underlying signaling mechanisms of the so-called intracellular ANG II in cardiovascular, neural, and renal systems. The purpose of this article is to provide a comprehensive review of the intracellular actions of ANG II, either administered directly into the cells or expressed as an intracellularly functional fusion protein, and its effects throughout a variety of target tissues susceptible to the impacts of an overactive ANG II, with a particular focus on the proximal tubules of the kidney. While continuously reaffirming the roles of extracellular or circulating ANG II in the proximal tubules, our review will focus on recent evidence obtained for the novel biological roles of intracellular ANG II in cultured proximal tubule cells in vitro and the potential physiological roles of intracellular ANG II in the regulation of proximal tubular reabsorption and blood pressure in rats and mice. It is our hope that the new knowledge on the roles of intracellular ANG II in proximal tubules will serve as a catalyst to stimulate further studies and debates in the field and to help us better understand how extracellular and intracellular ANG II acts independently or interacts with each other, to regulate proximal tubular transport and blood pressure in both physiological and diseased states.

Keywords: AT1 receptor, ANG I-converting enzyme, hypertension, intracrine, renin, signaling

our current understanding of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) has evolved a great deal since Tigerstedt and Bergman's discovery of renin as a “pressure-elevating substance” from the kidney (9, 37, 69, 76, 115). Although the endocrine role of the RAS is undisputable, there is now increasing evidence that the key member of the RAS, ANG II, may function as a paracrine (cell-to-cell) and intracrine (within the same cell or intracellular) peptide. Indeed, ANG II may be generated in a particular cell type and released extracellularly to exert an endocrine effect in a different cell in a remote tissue via activation of its cell surface G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Alternatively, newly formed ANG II may directly interact with its cytoplasmic and nuclear GPCRs to exert intracellular effects within the same cell (22, 33, 43, 75, 117, 121). A potential role of intracellular ANG II was initially implicated in an early study in the 1970s, in which radiolabeled ANG II was localized in the nuclei of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and cardiomyocytes after it was systemically infused into the rats (128). It is Re who has since the 1980s (126) persistently advocated the concept of intracrine ANG II as an effector peptide that is either synthesized within a cell via actions of renin, angiotensinogen, and ANG I-converting enzyme (ACE), or internalized from extracellular ANG II via receptor-mediated endocytosis (121, 124). This effort has led to an explosion of research activities to uncover a functional role of intracellular (or intracrine) ANG II in different tissues or cells in last two decades.

In the 1980s, Re and associates reported that intracellular ANG II induced important nuclear effects in isolated rat hepatocytes (19, 21, 126). In the 1990s, three groups of independent investigators confirmed that rat hepatic nuclei contained the receptor binding sites specific for ANG II (7, 38, 39, 151), and ANG II induced positive renin and angiotensinogen transcription and growth-related effects (38, 39). In the heart, De Mello's group (30–32) performed intracellular dialysis of renin, angiotensinogen, or ANG II directly into hamster cardiomyocytes and demonstrated significantly altered cell-to-cell communications, suggesting an important role for intracellular ANG II to regulate cardiac function. In VSMCs, Haller et al. (54, 56) elegantly microinjected ANG II directly into the cells and demonstrated significant intracellular and nuclear calcium responses, which were blocked by intracellularly administered AT1 receptor antagonists. In the brain, Sigmund and colleagues (75) recently provided evidence that an intracellular form of renin plays a functional role in the brain. Recent studies from Danser's and Mullins' groups reported that prorenin may be taken up by target cells to induce intracellular signaling or responses that may be independent of ANG II (26, 134). In the renal cortical nuclei of sheep and congenic mRen2 Lewis rats, Crowley et al. (23) and Chappell's team (50, 52, 53) characterized a large number of high-density specific receptors for ANG II and ANG (1–7), activation of which were associated with superoxide and/or nitric oxide production. Cook's team has elegantly designed an intracellular cyan fluorescent fusion of ANG II for its expression and actions only occur intracellularly (19–21). More recently, Redding et al. (127) have reported that transgenic mice expressing this intracellular fluorescent fusion of ANG II induced renal thrombotic microangiopathy and elevated blood pressure in mice. The presence and the potential role(s) of intracrine or intracellular ANG II in tissues other than the kidney have been comprehensively reviewed elsewhere (33, 43, 67, 121), as well as in the current issue of American Journal of Physiology Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology (5, 17, 51).

Accordingly, the scope of this article will focus on the intracrine and/or intracellular RAS in the kidney with a special emphasis on the proximal tubules. This is primarily because little is known about the presence and biological and physiological roles of intracellular ANG II in the kidney, let alone proximal tubules. The proximal tubules of the kidney reabsorb more than 65% to 70% of the filtered sodium and fluid loads, and increased sodium and fluid reabsorption by a few percentage points in this nephron segment by extracellular and intracellular ANG II may promote sodium and fluid retention and consequently lead to increases in arterial blood pressure. Currently, there is a consensus that extracellular ANG II induces powerful effects on proximal tubule function and tubule-interstitial injury by activating cell surface type 1 (AT1) receptors (35, 58, 99, 132, 171). However, it is unlikely that an endocrine or a paracrine role may fully explain the long-term hypertensive and genomic effects of ANG II, since repeated exposure or stimulation of the cell surface GPCRs by ANG II is known to induce desensitization of the responses through the so-called receptor-mediated endocytosis of the ANG II/receptor complex (40, 45, 154). Here, we review the evidence for a functional intracellular angiotensin system, specifically in proximal tubules of the kidney. We hope that this brief review may serve as a catalyst to stimulate further studies and constructive debates in this field, and ultimately improve our understanding of how extracellular and intracellular ANG II acts independently or through interactions to regulate proximal tubular sodium and fluid reabsorption and blood pressure in both physiological and diseased states. This information may also be useful for devising novel strategies to prevent or treat ANG II-dependent hypertension and cardiovascular and renal diseases by blocking the effects of both extracellular and intracellular/nuclear ANG II.

Overview of the Classic Role of Endocrine and Paracrine ANG II in the Kidney

ANG II is a powerful vasoactive peptide that is implicated as the major bioactive component of the RAS (11, 41, 72, 73, 102, 181, 182). The classic pathway for its production involves kidney-derived renin, which is the rate-limiting enzyme acting on angiotensinogen synthesized primarily in the liver, to form ANG I. ANG I is converted by ACE to the principle peptide ANG II. ANG II can be further degraded by aminopeptidases into biologically active fragments, including ANG III (des-aspartyl-ANG II), ANG (1–7), and ANG IV [ANG (3–8)] in the circulation and target tissues (11, 41, 72, 73, 102, 181, 182). The endocrine (or circulating) and paracrine (or intrarenal) roles of ANG II in the physiological control of renal hemodynamics and tubular sodium transport have been extensively investigated since the 1970s and 1980s (58, 59, 70, 78, 79, 99, 105, 118). It is now well understood that circulating and intrarenal ANG II activates its cell surface GPCRs in targeted cells, resulting in phosphorylation of the receptor and initiation of downstream signaling responses (28, 47, 63, 93, 154, 171, 181, 182). As in other target tissues, ANG II receptors exist as two major classes in most species in the kidney, designated AT1 and AT2, although the rodent AT1 exists as two further subtypes, AT1a and AT1b (10, 28, 66, 145, 171). Activation of AT1 is responsible for the majority of ANG II's well-recognized actions both in vitro and in vivo, such as renal vasoconstriction or hemodynamic responses and sodium and fluid reabsorption, with AT2 activation appearing to counter many of those effects induced by AT1 activation (28, 47, 63, 93, 154, 171, 181, 182). The development of ANG II receptor subtype-selective antagonists, such as losartan and candesartan on AT1 or PD123319 on AT2, and generation of transgenic mice with global or cell-specific deletion of a selective receptor have helped demonstrate the importance of ANG II and its cell surface GPCRs in the regulation of blood pressure, cell growth and proliferation, renal hemodynamics, sodium and fluid reabsorption, and cardiovascular homeostasis (28, 47, 63, 93, 154, 155, 171, 181, 182). The endocrine and/or paracrine roles of ANG II in the kidney have been comprehensively reviewed elsewhere (11, 28, 72, 77, 103, 145).

Overview of the Local Renin-Angiotensin System in Proximal Tubules of the Kidney

The proximal tubule is one of major target tissues of the RAS in the kidney, because the proximal tubule function is physiologically and pathophysiologically regulated by both circulating and local paracrine ANG II. All key components of the RAS, including angiotensinogen, renin, ACE, and AT1 and AT2 receptors, have been demonstrated in proximal tubules of the kidney (11, 61, 94, 101, 150, 173, 182). The presence of renin, angiotensinogen, and ACE in proximal tubules will ensure the onsite production of ANG II independent of the circulating RAS, whereas the expression of AT1 and AT2 receptors is critical for ANG II to induce biological and physiological effects. Up to four major classes of ANG receptors have been found to express in proximal tubules of the kidney, including AT1 and AT2 for ANG II (12, 50, 109, 147, 171, 173–175) and ANG III (des-aspartyl-ANG II) (60, 112, 113), the Mas receptors for ANG (1–7) (53, 133), and AT4 (or IRAP, insulin-regulated aminopeptidase) for ANG IV (Fig. 1) (3, 57, 80). High-affinity AT1 receptors are localized in both brush border and basolateral membranes (34, 36, 170, 173). AT1 receptors are GPCRs belonging to the superfamily of seven transmembrane-spanning protein receptors (28, 93, 98, 171). The AT1 receptor is further classified into two subtypes, AT1a and AT1b, in rodents, but the former is the predominant isoform in the kidney, equivalent to the human AT1 receptor (28). The classical actions of extracellular or exogenously administered ANG II in proximal tubules of the kidney are to stimulate sodium, bicarbonate, and fluid reabsorption physiologically (15, 58, 99, 176), and to induce sodium retention and tubulo-interstitial injury or fibrosis in diseased states (68, 91, 130, 163). AT1 (AT1a) receptors appear to mediate the majority of ANG II-induced biological and physiological effects in proximal tubules of the kidney (23, 24, 49), which is coupled to GPCR-mediated multiple signaling pathways, including PLC, PLD, and PLA2, MAPK, and tyrosine kinase (35, 93, 156, 173). AT1 receptor activation by ANG II leads to the hydrolysis of phosphoinositide, mobilization of intracellular calcium, and inhibition of adenylyl cyclase (81, 137, 153, 183).

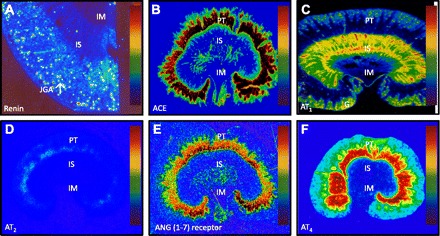

Fig. 1.

Quantitative in vitro autoradiographic mapping of active renin binding in juxtaglomerular apparatus (JGA) in the dog kidney pretreated with sodium depletion using the radiolabeled renin inhibitor, 125I-labeled H77 (A), angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) binding in proximal tubules of the rat kidney using 125I-labeled 351A (B), AT1 receptor in the presence of the AT2 receptor blocker PD123319 to displace AT2 receptors (C) or AT2 receptor binding in the presence of the AT1 receptor blocker losartan to displace AT1 receptors using 125I-labeled [Sar1, Ile8]-ANG II (D), ANG (1–7) receptor binding in the rat kidney using 125I-labeled ANG (1–7) as the radioligand (E), and ANG IV receptor binding in the rat kidney using 125I-labeled ANG (3–8) (F). The levels of binding are indicated by color calibration bars with red representing the highest, whereas blue showing the lowest levels of enzyme or receptor binding. G, glomerulus; IM, inner medulla; IS, inner stripe of the outer medulla; JGA, juxtaglomerular apparatus; PT, proximal tubule. Reprinted from Peptides, vol. 32, by Zhuo JL and Li XC, New insights and perspectives on intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: focus on intracrine/intracellular angiotensin II, pages 1551–1565, 2011, with permission from Elsevier (182).

AT2 receptors are also expressed in proximal tubules of the kidney. Although the expression of AT2 receptor mRNA is low in proximal tubules of the adult rat and mouse kidneys, AT2 receptor proteins are readily detectable by Western blot analysis (12, 109, 145). In adult human kidney, high levels of the AT2 receptor are localized in the perivascular or adventitial layers of intrarenal arteries (44, 48, 172). The specific roles and signaling transduction mechanisms of AT2 receptors in proximal tubules of the kidneys are not as well understood as those of AT1 receptors. However, Carey and colleagues (110–113, 144, 145) have consistently demonstrated that ANG II and ANG III activate AT2 receptors to induce significant diuresis and natriuresis via tubule-dependent mechanisms, involving activation of the nitric oxide (NO)/cGMP-dependent signaling pathway. In contrast to AT1 and AT2 receptors, the roles and signaling mechanisms of the Mas receptors for ANG (1–7) and the AT4 receptor for ANG IV in proximal tubules of the kidneys are not well understood (13, 41, 57, 80).

In contrast to the circulating RAS, which is inversely regulated by ANG II and blood pressure, the local RAS in proximal tubules appears to be differentially regulated by the agonist in ANG II-induced hypertension. Major components of the RAS, including angiotensinogen (71, 72, 103), ACE (61), ANG II (85, 90, 180, 184), and AT1 receptors (61, 90, 180) were significantly increased, rather than decreased, in ANG II-induced hypertension. In spontaneously hypertensive rats, ANG II also increased AT1 receptors in proximal tubule cells (166). This upregulation of the local proximal tubule RAS by ANG II may play an important role in the pathogenesis of ANG II-dependent hypertension.

Potential Roles for an Intracrine/Intracellular RAS in the Blood Pressure and Renal Regulation

Whether intracrine/intracellular ANG II has an important intracellular role and, if it does, what are the signaling mechanisms are incompletely understood (33, 73, 74, 121, 123, 178, 181, 182). The concept of intracrine/intracellular ANG II has not been well accepted for a number of reasons. Currently, the general view of ANG II-induced biological and physiological effects appears to be that after synthesis, ANG II may have to be released into the extracellular fluid compartments to induce any biological and physiological effects. The second general view is that ANG II receptors, after their expression, may have to appear on the cell surface or plasma membranes to mediate the effects induced by ANG II. The third general view is that cell surface AT1 (AT1a) receptors may be continuously desensitized after they are continuously exposed to extracellular ANG II and that internalized ANG II may have to be transported to lysosomes for degradation (40, 92, 93, 156, 167). According to the latter view, internalized ANG II and its receptors are unlikely to be trafficking to other intracellular organelles or the nucleus. However, there is strong evidence suggesting that binding of ANG II to its cell surface AT1 receptors also induces internalization of both the effector (ANG II) and the receptor into intracellular compartments, including the nucleus. Indeed, at least in the proximal tubules of the kidney, internalized ANG II, along with intracellularly synthesized ANG II, may serve as a major source of intracellular ANG II, which may interact with its cytoplasmic and nuclear AT1 or AT2 receptors to induce important intracellular signaling with consequent biological effects (82–88, 179, 183). Here, we review the in vitro and physiological evidence for a biological role of intracellular ANG II in cultured proximal tubule cells and proximal tubules of the kidney, with focuses on the mechanisms of AT1 (AT1a) receptor-mediated ANG II uptake (or endocytosis) and its contribution to intracellular ANG II levels, intracellular trafficking pathways, and the potential role of internalized or intracellular ANG II in the regulation of the sodium and hydrogen exchanger 3 (NHE3), proximal tubule reabsorption, and blood pressure.

Evidence that ANG II May Be Intracellularly Formed in Proximal Tubules

The concept that ANG II may be synthesized or formed in proximal tubule cells of the kidney is not quite controversial, as all necessary substrate and enzymes of the entire RAS that are required for ANG II formation are expressed locally (11, 61, 94, 101, 150, 173, 182). Alternatively, angiotensinogen and renin may also be taken up by proximal tubule cells for intracellular ANG II production. In proximal tubule cells, paracrine and intracellular ANG II may be generated by synthesis within the cell with or without secretion into the luminal fluid or interstitial fluid compartments (8, 61, 64, 65, 100, 101, 106, 139, 146, 150). It has been widely cited in the literature that ANG II concentrations may be in the ranges of 20–40 nM (or μg/ml) in intraproximal tubular and peritubular or interstitial fluid compartments, compared with femtomoles of ANG II (or pg/ml) present in the normal plasma samples (8, 139, 146). Although the reported nanomolar levels of ANG II in proximal tubule fluid and cortical interstitial fluid remains highly debatable (158, 159), there is evidence that ANG II appears to be capable of intracellular synthesis under particular conditions in a variety of cells. For instance, high glucose and isoproterenol have been found to stimulate production of intracellular ANG II in cardiac myocytes, renal mesangial cells, and VSMCs (141–143). By using receptor blockers, such as candesartan to inhibit extracellular binding and potential activation of the receptor-mediated endocytic pathway, it has been demonstrated that ANG II can be synthesized intracellularly and, depending on the cell types or conditions, may use an alternate pathway for synthesis from the well-described ACE-mediated pathway (114). For instance, in diabetes, hyperglycemia appears to promote a renin and chymase-dependent mechanism, which is not affected by ACE inhibitors, while isoproterenol stimulation of ANG II synthesis can be blocked with benazepril, an ACE-inhibitor (4, 114, 142, 143). The downstream fate of intracellularly synthesized ANG II is further dependent on the particular stimulus, for reasons not yet fully understood; ANG II synthesized after glucose stimulation tends to be retained within the cell, while isoproterenol-stimulated ANG II is secreted. A variety of components of the RAS, including renin, angiotensinogen, and ANG II, have been found to be dramatically increased intracellularly in high glucose or diabetic conditions in vitro. In vivo studies have further confirmed this intracellular activation within the heart and kidney or proximal tubule cells, with unaffected extracellular or plasma levels (4, 114, 142, 143, 168, 169). Clearly, there is a therapeutic potential for targeting long-term clinical implications of hyperglycemia-induced intracellular ANG II production in such pathologies as diabetic cardiomyopathy and diabetic nephropathy.

In cultured rabbit and mouse proximal tubule cells, we also demonstrated that intracellular ANG II levels are much higher in proximal tubule cell samples than in the medium under basal and ANG II-stimulated conditions, thereby supporting an independent, local RAS (82, 84, 86, 179). We found that high levels of ANG II in proximal tubule cells could be reduced by pretreatments of the cells with an ACE inhibitor or an AT1 receptor antagonist if the cells were incubated with ANG II. Likewise, intracellular ANG II levels in isolated proximal tubules were much higher than in plasma in the rat and C57BL/6J mice under basal and ANG II-infused conditions, which also appear to be ACE- and/or AT1 receptor-dependent (85, 87, 90, 107). Our studies suggest that glucose or isoproterenol, however, are not the only means for induction of intracellular synthesis of ANG II. In an interesting study, van Kats et al. (159) investigated whether ANG II generation occurs intracellularly or extracellularly by studying the subcellular localization of 125I-labeled ANG I or 125I-labeled ANG II in the pig kidney (159). These investigators found high levels 125I-labeled ANG I or 125I-labeled ANG II in all intracellular organelles with the same distribution profiles and came to a different conclusion that ANG II formation in the kidney occurs predominantly extracellularly, which is followed by rapid AT1 receptor-mediated endocytosis, thereby leading to high intracellular ANG II levels (157, 158). Furthermore, studies in isolated sheep nuclei from the kidney cortex suggest that ANG II be synthesized in the nucleus itself, as immunoreactive components of the entire RAS—angiotensinogen, renin, and ACE—were identified in the absence of the cytoplasm or extranuclear organelles (50).

Evidence that AT1 (AT1a) Receptor-Mediated Uptake of Circulating and/or Extracellular ANG II in Proximal Tubule Cells

The early evidence that the kidney takes up the circulating ANG II was provided by Navar and colleagues, who infused exogenous ANG II to raise the plasma ANG II level to that seen in two-kidney, one-clip (2K1C) renal hypertensive rats (160). These authors showed that while renin content was markedly suppressed by 80%, intrarenal ANG II content of the contralateral kidneys of the 2K1C and the ANG II-infused rats was greater than that of 2K1C control or uninephrectomized control animals. These results were subsequently confirmed by several other groups (140, 157, 158, 184, 185). These studies suggest that with high affinity and high density of AT1 receptors localized in apical and basolateral membranes of the proximal tubule cells, intraluminal and interstitial ANG II may be continuously taken up by proximal tubule cells in vitro and in vivo to serve as an important source of intracellular ANG II. However, the site(s) or cell type(s) responsible for intrarenal accumulation of ANG II is less well understood with the whole-kidney approach.

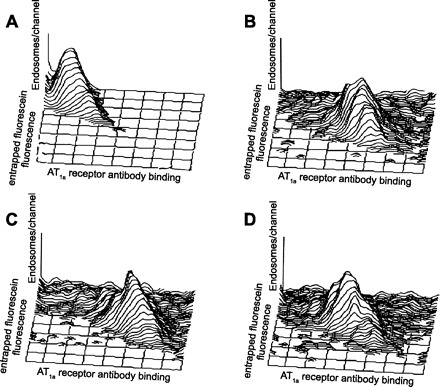

We first sought to determine whether the systemically infused ANG II is taken up into renal cortical endosomes during ANG II-induced hypertension, and if so, whether the AT1 receptor antagonist, candesartan, prevents this accumulation (180). We infused [Val5]-ANG II continuously for 2 wk rather than for hours via an osmotic minipump and isolated and purified heavy (intermicrovillar clefts) or light endosomes to determine endosomal ANG II levels. The levels of ANG II in light endosomes were almost 10-fold higher in ANG II-infused rats, where ANG II was colocalized with fluorescein-labeled AT1a receptor antibody binding and an endosomal marker (Fig. 2) (180). This finding provides strong evidence that the circulating and/or paracrine ANG II is taken up by the superficial cortex of the kidney, probably proximal tubules. The endocytosis of circulating and paracrine ANG II may also be taken up by proximal tubules via the scavenger receptor megalin-mediated mechanism (46, 119).

Fig. 2.

Colocalization of entrapped endosomal fluorescein-labeled dextran and AT1a receptor antibody binding using flow cytometry in light endosomes freshly isolated from the control rats, ANG II-infused rats, and rats treated concurrently with ANG II and the AT1 receptor blocker candesartan. Each panel displays data on 2,000 individual endosomes with axes on a log scale. For the entrapped fluorescence, the origin is at the top left corner. A: autofluorescence without entrapped endosomal fluorescein-labeled dextran and with minimal AT1a receptor antibody binding. B: colocalization of entrapped endosomal fluorescein-labeled dextran and AT1a receptor antibody binding in a control rat. C: colocalization of entrapped endosomal fluorescein dextran and AT1a receptor antibody binding in an ANG II-infused rat. D: colocalization of entrapped endosomal fluorescein dextran and AT1a receptor antibody binding in a rat treated concurrently with ANG II and candesartan. Note a marked right shift in three-dimensional frequency histogram in ANG II-infused rats, which was prevented by candesartan, indicating an increase in AT1a receptor antibody binding during long-term ANG II infusion and a return to control with concurrent candesartan treatment. From Zhuo JL, Imig JD, Hammond TG, Orengo S, Benes E, Navar LG. Ang II accumulation in rat renal endosomes during Ang II-induced hypertension: role of AT1 receptor. Hypertension 39: 116–121, 2002 (180).

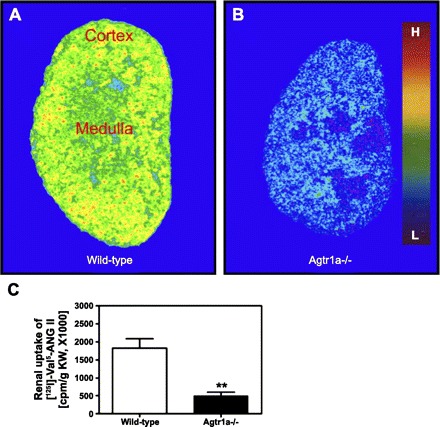

The endocytic pathway has commonly and long been thought to result primarily in degradation of the internalized molecules by directing them to the lysosomes for destruction or deactivation. However, recent research indicates that endosomes can serve as an intracellular platform for continuous receptor signaling, for example, the MAP kinase ERK1/2 signaling (25, 40, 92, 95, 97, 167). Moreover, internalized ANG II and AT1 receptors may also be targeted to the nucleus (14, 19, 84, 88, 96, 182). ANG II along with its AT1 receptors can be taken up, in part, through the classical clathrin-coated pits in VSMCs or through cytoskeleton microtubule-dependent mechanisms in proximal tubule cells (40, 62, 82, 84, 85, 87, 92, 154). The current dogma holds that the receptor is then recycled back to the plasma membrane for reactivation by circulating and paracrine ANG II. However, recent research indicates that the receptor might be trafficked to the nucleus, in addition to the membranes, thereby possibly facilitating downstream long-term genetic or transcriptional effects by intracellular ANG II, as ANG II receptors have been identified both within endosomes (Fig. 2) and the nucleus of proximal tubules or renal cortical cells (Fig. 3) (50, 82, 84, 88, 116, 180). Our in vitro studies in proximal tubule cells supports a microtubule-dependent pathway, as opposed to the canonical clathrin-coated pit pathway (82, 84); additionally, a nuclear localization sequence on the AT1a receptor has recently been discovered and may be involved in intracellular nuclear trafficking, of both the receptor and of ANG II (14, 96). AT1 receptors are present on both the basolateral and the apical membranes of proximal tubule cells, and both are capable of undergoing endocytosis. Indeed, much of ANG II signaling on the apical membranes is at least, in part, dependent on endocytosis, and blockade of internalization inhibits sodium flux and PLC activation (135–137, 152). However, blockade of the AT1a receptor endocytosis on the basolateral membranes appears to have no effect (152). AT2 receptors, however, are not thought to undergo internalization and trafficking upon agonist stimulation and the source and purpose of intracellular AT2 receptors are not yet fully elucidated (16, 50, 62). Both receptor types have been found on the nuclear membranes of different cell types, and it is likely that both receptors have a function in gene transcription (16, 50, 62, 88, 89, 149). So far, we have evidence that circulating and/or paracrine ANG II is accumulated within renal endosomes or isolated proximal tubules of ANG II-induced hypertensive rodent models (85, 87, 90, 180). This accumulation of ANG II appears to be predominantly mediated by the AT1 (AT1a) receptor in rodent kidneys, as demonstrated in AT1a receptor-knockout mice (Fig. 4) (85, 87).

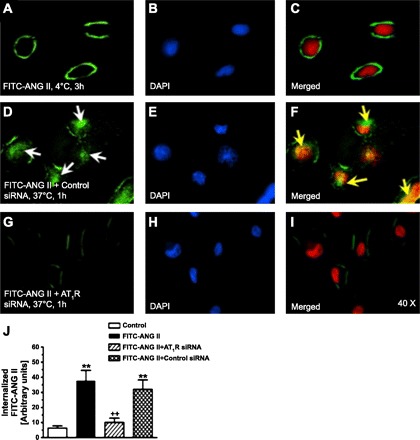

Fig. 3.

Effects of the knockdown of AT1 receptor (AT1R) expression with AT1 siRNAs on AT1R-mediated uptake of FITC-labeled ANG II in rabbit proximal tubule (PT) cells. A–C: FITC-ANG II- (green, white arrows) and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-stained (blue in B or red in merged image C for optimal visualization) nuclei in PT cells incubated with FITC-ANG II (1 nM) at 4°C for 3 h. FITC-ANG II was restricted to the cell surface (white arrows). D–F: AT1-mediated uptake of FITC-ANG II in PT cells pretransfected with control siRNAs for 48 h and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Control siRNAs had no effect on FITC-ANG II uptake; thus, FITC-ANG II was seen in the supranuclear regions and nuclei (F, yellow arrows). G–I: AT1R-mediated uptake of FITC-ANG II was blocked in PT cells pretransfected with AT1R siRNAs for 48 h. J: semiquantitated levels of FITC-ANG II uptake. Magnification: ×40. **P < 0.01 vs. control PT cells incubated with FITC-ANG II at 4°C for 3 h. ++P < 0.01, untransfected (FITC-ANG II) vs. specific siRNA-transfected PT cells incubated with FITC-ANG II at 37°C for 1 h. [From Li et al. (84).]

Fig. 4.

Visualization of intracellular uptake of 125I-labeled Val5-ANG II in kidneys of wild-type (C57BL/6J) and AT1a receptor knockout mice by quantitative in vivo autoradiography (A and B). Intracellular 125I-labeled Val5-ANG II in the kidney was determined after kidneys were perfused with an acidic buffer to clear blood and cell surface receptor-bound 125I-labeled Val5-ANG II. Levels of 125I-labeled Val5-ANG II uptake are keyed to the color calibration bar, with red representing the highest (H) and blue the background (L) level of uptake. C: quantitated intracellular 125I-labeled Val5-ANG II. **P < 0.01 vs. wild-type. [From Li and Zhuo (87).]

In Vitro Evidence that Intracellular ANG II Induces Intracellular and Nuclear Effects in Proximal Tubule Cells

ANG II is a well-recognized vasoactive peptide hormone in the physiological regulation of proximal tubular sodium and fluid transport and blood pressure homeostasis (15, 58, 99, 138, 176). ANG II is also a well-documented growth and transcriptional factor, cytokine, or chemokine in the development and progression of chronic pathologies, including hypertensive kidney diseases and diabetic nephropathy through its proinflammatory and growth-promoting effects (2, 89, 130, 131, 148, 161, 162, 164, 177, 179). Although the best-recognized effects are mediated by extracellular ANG II acting on cell surface receptors, we and others have gathered evidence during last few years that intracellular ANG II or its major metabolite ANG (1–7) may induce important intracellular and nuclear effects in the proximal tubule cells or the freshly isolated renal cortical nuclei (50, 52, 53, 86, 88, 89, 116, 181, 183). The demonstrated internalization of extracellular ANG II along with AT1 receptors, as previously discussed, and the identification of AT1 and AT2 receptors on in freshly isolated intact nuclei of kidney cells strongly suggest downstream effects at the genetic or transcriptional level (50, 52, 53, 86, 88, 89, 116, 181, 183). For instance, intracellular ANG II has been found to upregulate transcription of precursor components of the RAS itself, such as renin and ACE, and in this way, can increase its own production (103, 104). Recent in vitro studies in a tubular epithelial cell line indicate that chronic exposure to ANG II increased NHE3 promoter activity, apparently through the interplay of several intracellular signaling mechanisms (120). Unfortunately, intracellular activation of AT1 receptor compared with cell membrane activation was not determined in this study (120).

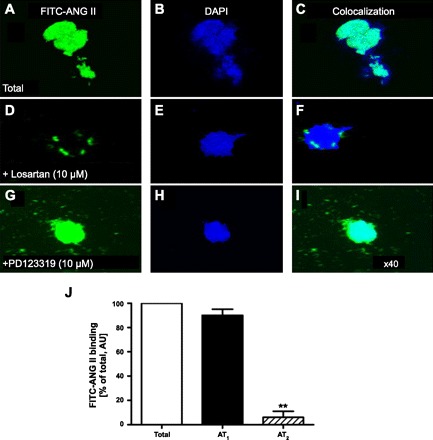

We recently tested the hypothesis that intracellular ANG II directly induces transcriptional effects in the nucleus of rat renal cortical cells by stimulating AT1a receptors (88). In our study, the nuclei with an intact nuclear membrane, but devoid of cell surface membranes or other intracellular organelles, were freshly isolated from the rat renal cortex. Both FITC-labeled ANG II and 125I-labeled Val5-ANG II bound the nuclei with a predominance of AT1 receptors (Fig. 5). RT-PCR confirmed that AT1a mRNAs predominated in these nuclei. In freshly isolated nuclei stimulated by ANG II, in vitro transcription of mRNAs for transforming growth factor-β1, macrophage chemoattractant protein-1, and NHE3 were all significantly increased (88). Because these transcriptional responses to ANG II were induced by the agonist in isolated nuclei, devoid of cell surface receptor-mediated signaling and completely blocked by losartan, we suggested that ANG II may directly stimulate nuclear AT1a receptors to induce transcriptional responses that may be associated with proximal tubular sodium transport, cellular growth and hypertrophy, and proinflammatory responses, especially in chronically elevated ANG II states. Interestingly, in a recent study, Tadevosyan et al. (149) confirmed that cardiomyocyte nuclear membranes also possess ANG II receptors that couple to nuclear signaling pathways and regulate transcription. Furthermore, Chappell and colleagues (50, 53, 116) have demonstrated that the renal cortical nuclei have receptor binding sites specific for AT1, AT2, and ANG (1–7), stimulation of which led to increased production of superoxide or nitric oxide. These studies, along with ours, provide further support for a nuclear role for intracellular ANG II.

Fig. 5.

Localization of ANG II receptors in freshly isolated rat renal cortical nuclei using FITC-labeled ANG II. A, D, and G: total FITC-ANG II receptor binding. B, E, and H: DAPI-labeled nucleic acids in the same isolated nuclei. C, F, and I: merged images of FITC-ANG II binding and DAPI-labeled nucleic acids in the same nucleus. J: levels of AT1 (>90%) and AT2 receptor binding (<10%) as a percentage of total FITC-ANG II binding. Magnification: ×40. AU, arbitrary fluorescence intensity unit. **P < 0.01 vs. AT1 binding. [From Li and Zhuo (88).]

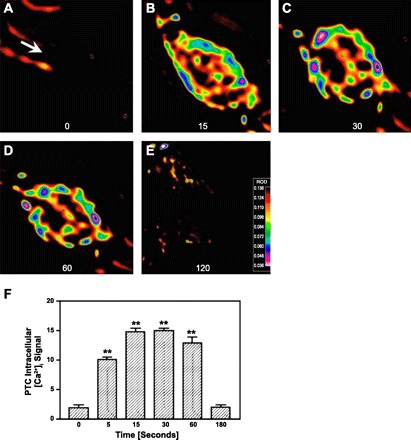

The signal mechanisms by which ANG II induces increases in transcriptional responses at the nuclear level are currently not yet fully understood. However, the effects of ANG II on intracellular calcium, a major downstream intracellular signaling for hormone-mediated actions, might, at least in part, play a significant role (29, 33, 43, 54, 55, 121, 181–183). Indeed, Haller et al. (54, 55) reported that intracellular ANG II-induced increases in cytoplasmic [Ca2+] were rapidly followed by a rise in intranuclear [Ca2+], suggesting an important role of cytoplasmic [Ca2+] response. This may be applied to proximal tubule cells as well. In single rabbit proximal tubules cells, we demonstrated that in vitro microinjection of ANG II directly into single rabbit proximal tubules also significantly induced intracellular [Ca2+] responses that could be observed in the nucleus (Fig. 6) and that comicroinjection of the AT1 receptor blocker losartan with ANG II effectively blocked the intracellular ANG II-induced cytoplasmic and nuclear [Ca2+] responses (181–183). In contrast, studies by Baker and Kumar (6), using a nonsecreted form of recombinant ANG II, demonstrated that the AT1 receptor or an AT1-like receptor is not necessary for ANG II to induce intracrine mitogenic effects in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. One explanation for this activation in the absence of a known receptor is that ANG II could interact directly with chromatin and induce gene expression in a manner similar to PDGF and insulin (6, 22, 122). Studies in A7r5 VSMCs, which do not express extracellular ANG II receptors and, therefore, do not normally respond to extracellular ANG II, have shown an influx of Ca2+ with the introduction of intracellular ANG II (42). Unlike in proximal tubule cells, intracellular ANG II-dependent Ca2+ response could not be blocked with extracellular or intracellular addition of AT1 or AT2 receptor blockers, indicating activation of the Ca2+ responses proceeded by a mechanism that does not rely on any known receptors (6, 142). However, intracellular administration of ANG II in these cells also stimulated cell proliferation, which, unlike Ca2+ responses, could be partially blocked both by AT1 and AT2 receptor antagonists (73, 143). Additionally, activation of AT2 or ANG (1–7) receptors in the nuclei of sheep kidney cells has been found to promote nitric oxide signaling and inhibits production of renin (50, 53). It is not yet known whether AT2 and ANG (1–7) receptors play a role at the genetic level in a similar fashion to AT1 receptors.

Fig. 6.

Effect of intracellular microinjection of ANG II (1 nM, ∼70–100 fl) on [Ca2+]i responses in single PT cells at baseline (0 s; A) and 15 (B), 30 (C), 60 (D), and 120 (E) s after microinjection of ANG II in the cells. F: relative levels of [Ca2+]i signaling before and after microinjection of ANG II. ROD, relative optical density. Red represents the highest level of [Ca2+]i responses, whereas black is the background. **P < 0.01 vs. basal. [From Zhuo et al. (183).]

Evidence that Intracellular ANG II May Have Mitochondrial Effects

Whether intracellular ANG II has mitochondria-specific effects remains to be further studied (1, 125). Mitochondria are indispensible organelles in eukaryotic cell survival, responsible for energy production, as well as for the generation of reactive oxygen species (125). The mitochondria have been implicated in a number of age-related pathologies, including hypertension, renal disease, and atherosclerosis (27, 125). AT1 and AT2 receptors have been localized not only in the nuclei, but also in the mitochondria of a variety of cell types (1, 27, 125). A number of observations indicate ANG II elicits some of its pathophysiological effects directly through its interactions with AT1 on the mitochondria; many of these interactions may lead to increased autophagy and decreased mitochondria number in the affected cells (27, 125, 165). Conversely, functional AT2 receptors have been recently localized in the mitochondria of human monocytes, cardiac myocytes, and renal tubular cells, where ANG II stimulated AT2 receptors to produce nitric oxide (1). This is an exciting area of research that should be explored further for studying long-term genomic and/or transcriptional effects of intracellular/mitochondrial ANG II mediated by AT1 or AT2 receptors.

In Vivo Evidence for a Physiological Role of Intracellular ANG II in Proximal Tubular Reabsorption and Blood Pressure Regulation

Whether intracellular ANG II has a physiological role in the regulation of proximal tubular sodium and fluid reabsorption and blood pressure was only recently investigated but still remains poorly understood. As previously discussed, ANG II exerts diverse biological effects in cardiovascular and proximal tubule cells of the kidney in vitro, which include increases in intracellular and/or nuclear [Ca2+] (33, 54, 55, 183), increased production of superoxide or nitric oxide (50, 53, 116), increases in proximal tubular cellular NHE3 expression (84, 86), and increased nuclear transcriptional responses in growth factor(s) or proliferative cytokines (18, 20, 88, 89, 179). These in vitro findings strongly suggest a physiological role for intracellular ANG II in proximal tubules of the kidney. Indeed, ANG II is widely recognized to play an important physiological role in blood pressure homeostasis, as well as in the development of hypertension and hypertension-induced target organ injury. At least some of these effects are mediated through its extracellular and intracellular actions on proximal tubules of the kidney. Chronic infusion of ANG II is known to downregulate its AT1 receptors in many target cells but not proximal tubule cells, where AT1 receptor expression remains upregulated in response to ANG II (103, 104, 182). Continuous upregulation of AT1 receptors in proximal tubules of the kidney in the presence of high intratubular and interstitial ANG II levels may have important implications in hypertension.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs have become the first lines of treatments for hypertension and diabetic nephropathy. The studies of the intracellular RAS may have important implications for the future of hypertension treatment. Many ARBs are less effective at blocking intracellular ANG II-induced effects due to limited cell permeability. As previously discussed, glucose-induced intracellular ANG II synthesis is not dependent on ACE, rendering ACE-inhibitors less effective (73, 142, 143). However, it has been difficult to discover the effects of intracellular ANG II because of a lack of approaches that can differentiate the effects induced by intracellular ANG II via cytoplasmic and nuclear receptors from those induced by extracellular ANG II acting on the cell surface receptors. Recently, Cook and colleagues (127) developed a transgenic mouse model for the first time that expresses an intracellular ANG II protein that fuses to the downstream of enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP)/ANG II. These mice expressing ECFP/ANG II have their basal blood pressure significantly higher than in nontransgenic control counterparts. Because the transgene was expressed in all tested tissue with no circulating fusion proteins discovered in the plasma, the blood pressure-increasing effect was entirely dependent on the intracellular ANG II fusion protein. Additionally, VSMCs were found to proliferate despite normal levels of plasma ANG II (127). This is the first study to show that the global expression of an intracellular ANG II fusion protein may increase blood pressure and induce intrarenal microangiopathy in mice. However, this study does not explore the effects of intracellular expression of this fusion protein in proximal tubules of the kidney.

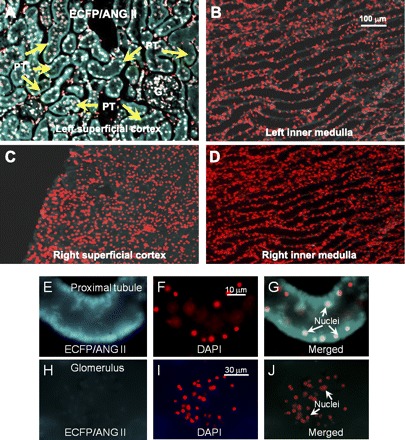

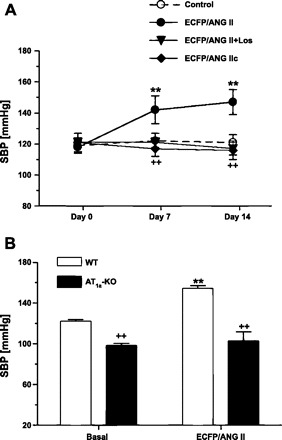

We have recently sought to test the hypothesis that proximal tubule-specific expression of an intracellular cyan fluorescent fusion of ANG II via intrarenal adenoviral gene transfer selectively in proximal tubules of the kidney may alter proximal tubular reabsorption and blood pressure in rats and mice (83). We developed an adenoviral construct encoding a nonsecreted form of ANG II, ECFP/ANG II, and a proximal tubule cell-specific promoter, sglt2 (129), which was used to drive ECFP/ANG II expression selectively in proximal tubules of the kidney. In both rats and C57BL/6J mice, time-dependent expression of ECFP/ANG II selectively in proximal tubules of the kidney (Fig. 7) and increases in blood pressure were demonstrated, accompanied by 24-h decreases in urinary sodium and lithium excretion. Because the blood pressure-elevating effect of ECFP/ANG II was blocked by concurrent losartan treatment and in AT1a receptor-knockout mice, we suggest this effect is mediated by AT1 (AT1a) receptors (Fig. 8) (83). This proximal tubule-specific expression of intracellular ANG II resulted in blood pressure increases comparable to those seen in transgenic mice globally expressing intracellular ANG II (127). However, blood pressure increased by proximal tubule-specific expression of intracellular ANG II were still much smaller than in rodents chronically infused with exogenous ANG II, as we reported previously (85, 87, 90, 180). The mechanisms in which AT1a receptors are involved in this blood pressure increase induced by ECFP/ANG II is not fully understood, but it is likely that increases in sodium and fluid reabsorption as a result of increased NHE3 expression may be involved. In vitro studies have shown that ANG II stimulation of AT1a receptors on proximal tubule cells or freshly isolated renal cortical cell nuclei could induce NHE3 transcriptional responses (84, 86, 182). More studies should be directed to further study the signaling mechanisms by which intracellular ANG II induced physiological responses in vivo, including proximal tubular transport responses and blood pressure.

Fig. 7.

Proximal tubule-selective expression of an intracellular enhanced cyan fluorescent fusion of ANG II (ECFP/ANG II) in the rat kidney 2 wk after intrarenal adenoviral transfer in the superficial cortex. A: specific ECFP/ANG II expression in proximal tubules of the left kidney, which received ECFP/ANG II transfer. B: lack of ECFP/ANG II expression in the left inner medulla. C: lack of ECFP/ANG II expression in the right contralateral renal cortex. D: lack of ECFP/ANG II expression in the right contralateral inner medulla. Please note that ECFP/ANG II proteins are shown as blue-green (cyan), whereas nuclear DNA is stained with DAPI and converted into the red color for better visualization. G, glomerulus. PT, proximal tubules. Scale bar = 100 μm. [From Li et al. (83).]

Fig. 8.

Effects of proximal tubule-specific transfer of an intracellular cyan fluorescent fusion of ANG II (ECFP/ANG II) or its scrambled control, ECFP/ANG IIc, with or without losartan treatment on systolic blood pressure in rats (SBP; A) or ECFP/ANG II transfer in wild-type or AT1a-KO mice (B). **P < 0.01 vs. basal SBP. ++P < 0.01 vs. SBP in ECFP/ANG II-transferred rats. [From Li et al. (83).]

Perspectives and Significance

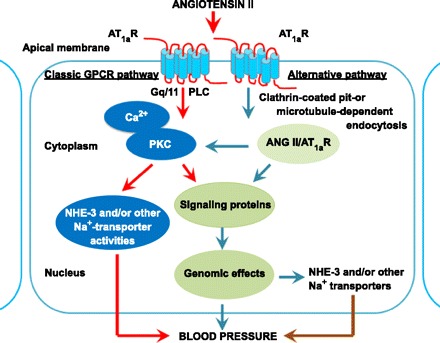

In summary, we have reviewed the progress recently made on the novel roles and signaling pathways of intracrine and/or intracellular ANG II in cardiovascular, renal, and blood pressure regulation with a focus on proximal tubules of the kidney (Fig. 9). Although it still remains incompletely understood and often debatable, recent studies generally support an intracellular and/or nuclear role for ANG II and other members of the RAS in cardiovascular, renal, and neural systems. In proximal tubules of the kidney, we now have functional evidence that circulating and paracrine ANG II is internalized via AT1 (AT1a) receptor-mediated endocytosis (or uptake), which contributes significantly to high levels of intracellular ANG II in this tubular segment. Upon internalization, not all ANG II and AT1 receptors are transported to lysosomes for destruction or for desensitization as widely expected, since internalized ANG II and its receptors can be readily visualized in other intracellular organelles and the nucleus, and importantly, long-term infusion of ANG II leads to persistent hypertension and target organ injury. We also have the physiological evidence that ANG II, when administered or expressed intracellularly in proximal tubular cells, may induce significant intracellular and nuclear responses. In cultured proximal tubule cells, intracellular ANG II may directly stimulate cytoplasmic and nuclear AT1 (AT1a) receptors to mobilize intracellular [Ca2+] and activates nuclear transcription factor NF-κB, leading to increased expression or transcription of NHE3 and proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors in proximal tubule cells. Indeed, augmented intrarenal NF-κB activity appears to play an important role in the development of ANG II-induced hypertension renal injury (2, 108). Under physiological conditions, intrarenal adenoviral transfer of an intracellular cyan fluorescent fusion of ANG II in proximal tubules of the kidney selectively increases proximal tubular reabsorption and blood pressure in rats and mice. Our studies suggest that increased expression and/or activity of NHE3 and proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors by intracellular ANG II may at least, in part, contribute to sodium retention and tubulo-interstitial injury in ANG II-induced hypertension. However, more studies are required to further elucidate the precise roles and signaling mechanisms of the intracellular RAS in proximal tubules of the kidney, especially underlying the long-term genomic or transcriptional effects of intracellular ANG II and its nuclear receptors and how their interactions affect transcriptional responses. Furthermore, it may be necessary to generate various transgenic animals, which express the so-called intracellular ANG II in a cell- or tissue-specific manner with or without the enzyme renin or ACE or a particular receptor for ANG II, to facilitate the studies on long-term physiological roles of intracellular and/or intracrine ANG II or other biologically active ANG fragments. Clearly, in the future, improved understanding of the intracellular RAS may have important therapeutic and clinical implications in the development of new strategies or drugs to block the long-term genomic or transcriptional effects of intracellular ANG II and its nuclear receptors in diabetes, progressive renal diseases, and hypertension.

Fig. 9.

A schematic representation showing that extracellular ANG II may induce short-term physiological responses in proximal tubule cells of the kidney through the classic cell surface GPCR-mediated signaling pathways, or long-term genomic and/or transcriptional responses mediated by internalized ANG II and AT1a receptors under pathophysiological conditions. The classic GPCR-mediated signaling pathways play an essential role in the physiological regulation of proximal tubular sodium, solute, and fluid transport by acutely altering the activities of NHE3 and other sodium transporters. Alternatively, the persistent elevation in the circulating and tissue ANG II levels, such as during ANG II-dependent hypertension, continuously increases AT1 (AT1a) receptor-mediated uptake of ANG II by proximal tubules of the kidney. Internalized ANG II may act as an intracellular peptide to activate cytoplasmic and nuclear receptors to induce long-term genomic or transcriptional effects on the expression of NHE3 and other sodium transporters, growth factors, and cytokines, with the consequences of increased sodium retention and development of hypertension and tubulointerstitial injury in the kidney.

GRANTS

The work as described in this article was supported in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease Grants (5RO1DK067299, 2R56DK067299-06, and 2RO1DK067299-07), the National Kidney Foundation of Michigan, the American Heart Association Grant-in-Aids, and the American Society of Nephrology M. James Scherbenske Grant to Dr. Jia L. Zhuo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We apologize to other outstanding investigators whose work has not been included in this review due to the topics selected and space restriction.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abadir PM, Foster DB, Crow M, Cooke CA, Rucker JJ, Jain A, Smith BJ, Burks TN, Cohn RD, Fedarko NS, Carey RM, O'Rourke B, Walston JD. Identification and characterization of a functional mitochondrial angiotensin system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 14849–14854, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Acres OW, Satou R, Navar LG, Kobori H. Contribution of a nuclear factor-κB binding site to human angiotensinogen promoter activity in renal proximal tubular cells. Hypertension 57: 608–613, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Albiston AL, Yeatman HR, Pham V, Fuller SJ, Diwakarla S, Fernando RN, Chai SY. Distinct distribution of GLUT4 and insulin regulated aminopeptidase in the mouse kidney. Regul Pept 166: 83–89, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baker KM, Chernin MI, Schreiber T, Sanghi S, Haiderzaidi S, Booz GW, Dostal DE, Kumar R. Evidence of a novel intracrine mechanism in angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Regul Pept 120: 5–13, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baker KM, Kumar R. Intracellular angiotensin II induces cell proliferation independent of AT1 receptor. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C995–C1001, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Booz GW, Conrad KM, Hess AL, Singer HA, Baker KM. Angiotensin-II-binding sites on hepatocyte nuclei. Endocrinology 130: 3641–3649, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Braam B, Mitchell KD, Fox J, Navar LG. Proximal tubular secretion of angiotensin II in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 264: F891–F898, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Campbell DJ. Circulating and tissue angiotensin systems. J Clin Invest 79: 1–6, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carey RM. Update on the role of the AT2 receptor. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 14: 67–71, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carey RM, Siragy HM. Newly recognized components of the renin-angiotensin system: potential roles in cardiovascular and renal regulation. Endocr Rev 24: 261–271, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carey RM, Wang ZQ, Siragy HM. Role of the angiotensin type 2 receptor in the regulation of blood pressure and renal function. Hypertension 35: 155–163, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chappell MC. Emerging evidence for a functional angiotensin-converting enzyme 2-angiotensin-(1–7)-Mas receptor axis: more than regulation of blood pressure? Hypertension 50: 596–599, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen R, Mukhin YV, Garnovskaya MN, Thielen TE, Iijima Y, Huang C, Raymond JR, Ullian ME, Paul RV. A functional angiotensin II receptor-GFP fusion protein: evidence for agonist-dependent nuclear translocation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F440–F448, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cogan MG. Angiotensin II: a powerful controller of sodium transport in the early proximal tubule. Hypertension 15: 451–458, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Conchon S, Monnot C, Teutsch B, Corvol P, Clauser E. Internalization of the rat AT1a and AT1b receptors: pharmacological and functional requirements. FEBS Lett 349: 365–370, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cook JL, Re RN. Transgenic mice expressing an intracellular fluorescent fusion of angiotensin II in target tissues. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol (December 14, 2011). doi10.1152/ajpregu.00493.2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cook JL, Giardina JF, Zhang Z, Re RN. Intracellular angiotensin II increases the long isoform of PDGF mRNA in rat hepatoma cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 34: 1525–1537, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cook JL, Mills SJ, Naquin R, Alam J, Re RN. Nuclear accumulation of the AT1 receptor in a rat vascular smooth muscle cell line: effects upon signal transduction and cellular proliferation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 40: 696–707, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cook JL, Re R, Alam J, Hart M, Zhang Z. Intracellular angiotensin II fusion protein alters AT1 receptor fusion protein distribution and activates CREB. J Mol Cell Cardiol 36: 75–90, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cook JL, Zhang Z, Re RN. In vitro evidence for an intracellular site of angiotensin action. Circ Res 89: 1138–1146, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cook JL, Singh A, Deharo D, Alam J, Re RN. Expression of a naturally occurring angiotensin AT1 receptor cleavage fragment elicits caspase-activation and apoptosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 301: C1175–C1185, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Oliverio MI, Pazmino AK, Griffiths R, Flannery PJ, Spurney RF, Kim HS, Smithies O, Le TH, Coffman TM. Distinct roles for the kidney and systemic tissues in blood pressure regulation by the renin-angiotensin system. J Clin Invest 115: 1092–1099, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crowley SD, Zhang J, Herrera M, Griffiths RC, Ruiz P, Coffman TM. The role of AT1 receptor-mediated salt retention in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F1124–F1130, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Daaka Y, Luttrell LM, Ahn S, Della Rocca GJ, Ferguson SS, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Essential role for G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis in the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 273: 685–688, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Danser AH, Deinum J. Renin, proreinin and the putative (pro)renin receptor. Hypertension 46: 1069–1076 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Cavanagh EM, Inserra F, Ferder L. Angiotensin II blockade: a strategy to slow ageing by protecting mitochondria? Cardiovasc Res 89: 31–40, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, Wright JW, Unger T. International union of pharmacology. XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacol Rev 52: 415–472, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. De Mello WC. Is an intracellular renin-angiotensin system involved in control of cell communication in heart? J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 23: 640–646, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. De Mello WC. Renin-angiotensin system and cell communication in the failing heart. Hypertension 27: 1267–1272, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. De Mello WC. Intracellular angiotensin II regulates the inward calcium current in cardiac myocytes. Hypertension 32: 976–982, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. De Mello WC. Renin increments the inward calcium current in the failing heart. J Hypertens 24: 1181–1186, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. De Mello WC, Danser AH. Angiotensin II and the heart: on the intracrine renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension 35: 1183–1188, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Douglas JG. Angiotensin receptor subtypes of the kidney cortex. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F1–F7, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Douglas JG, Hopfer U. Novel aspect of angiotensin receptors and signal transduction in the kidney. Annu Rev Physiol 56: 649–669, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dulin NO, Ernsberger P, Suciu DJ, Douglas JG. Rabbit renal epithelial angiotensin II receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 267: F776–F782, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dzau VJ. Theodore Cooper Lecture: Tissue angiotensin and pathobiology of vascular disease: a unifying hypothesis. Hypertension 37: 1047–1052, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eggena P, Zhu JH, Clegg K, Barrett JD. Nuclear angiotensin receptors induce transcription of renin and angiotensinogen mRNA. Hypertension 22: 496–501, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eggena P, Zhu JH, Sereevinyayut S, Giordani M, Clegg K, Andersen PC, Hyun P, Barrett JD. Hepatic angiotensin II nuclear receptors and transcription of growth- related factors. J Hypertens 14: 961–968, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ferguson SS. Evolving concepts in G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis: the role in receptor desensitization and signaling. Pharmacol Rev 53: 1–24, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ferrario CM, Varagic J. The ANG-(1–7)/ACE2/mas axis in the regulation of nephron function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F1297–F1305, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Filipeanu CM, Brailoiu E, Kok JW, Henning RH, De ZD, Nelemans SA. Intracellular angiotensin II elicits Ca2+ increases in A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol 420: 9–18, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Filipeanu CM, Henning RH, Nelemans SA, de Zeeuw D. Intracellular angiotensin II: from myth to reality? J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2: 219–226, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Goldfarb DA, Diz DI, Tubbs RR, Ferrario CM, Novick AC. Angiotensin II receptor subtypes in the human renal cortex and renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 151: 208–213, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gonzalez-Gaitan M. Signal dispersal and transduction through the endocytic pathway. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 213–224, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gonzalez-Villalobos R, Klassen RB, Allen PL, Navar LG, Hammond TG. Megalin binds and internalizes angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F420–F427, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Griendling KK, Lassegue B, Alexander RW. Angiotensin receptors and their therapeutic implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 36: 281–306, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Grone HJ, Simon M, Fuchs E. Autoradiographic characterization of angiotensin receptor subtypes in fetal and adult human kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 262: F326–F331, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gurley SB, Riquier-Brison AD, Schnermann J, Sparks MA, Allen AM, Haase VH, Snouwaert JN, Le TH, McDonough AA, Koller BH, Coffman TM. AT1A angiotensin receptors in the renal proximal tubule regulate blood pressure. Cell Metab 13: 469–475, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gwathmey T, Shaltout HA, Pendergrass KD, Pirro NT, Figueroa JP, Rose JC, Diz DI, Chappell MC. Nuclear angiotensin II-type 2 (AT2) receptors are functionally linked to nitric oxide production. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F1484–F1493, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gwathmey TM, Alzayadneh EM, Pendergrass KD, Chappell MC. Novel roles of nuclear angiotensin receptors and signaling mechanisms. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol (December 14, 2011). doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00525.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gwathmey TM, Pendergrass KD, Reid SD, Rose JC, Diz DI, Chappell MC. Angiotensin-(1–7)-angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 attenuates reactive oxygen species formation to angiotensin II within the cell nucleus. Hypertension 55: 166–171, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gwathmey TM, Westwood BM, Pirro NT, Tang L, Rose JC, Diz DI, Chappell MC. Nuclear angiotensin-(1–7) receptor is functionally coupled to the formation of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F983–F990, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Haller H, Lindschau C, Erdmann B, Quass P, Luft FC. Effects of intracellular angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 79: 765–772, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Haller H, Lindschau C, Quass P, Distler A, Luft FC. Nuclear calcium signaling is initiated by cytosolic calcium surges in vascular smooth muscle cells. Kidney Int 46: 1653–1662, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Haller H, Lindschau C, Quass P, Luft FC. Intracellular actions of angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 10 Suppl 11: S75–S83, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Handa RK, Krebs LT, Harding JW, Handa SE. Angiotensin IV AT4-receptor system in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F290–F299, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Harris PJ, Navar LG. Tubular transport responses to angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 248: F621–F630, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Harris PJ, Young JA. Dose-dependent stimulation and inhibition of proximal tubular sodium reabsorption by angiotensin II in the rat kidney. Pflügers Arch 367: 295–297, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Harris PJ, Zhuo JL, Skinner SL. Effects of angiotensins II and III on glomerulotubular balance in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 14: 489–502, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Harrison-Bernard LM, Zhuo J, Kobori H, Ohishi M, Navar LG. Intrarenal AT1 receptor and ACE binding in ANG II-induced hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F19–F25, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hein L, Meinel L, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ, Kobilka BK. Intracellular trafficking of angiotensin II and its AT1 and AT2 receptors: evidence for selective sorting of receptor and ligand. Mol Endocrinol 11: 1266–1277, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Higuchi S, Ohtsu H, Suzuki H, Shirai H, Frank GD, Eguchi S. Angiotensin II signal transduction through the AT1 receptor: novel insights into mechanisms and pathophysiology. Clin Sci (Lond) 112: 417–428, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Imig JD, Navar GL, Zou LX, O'Reilly KC, Allen PL, Kaysen JH, Hammond TG, Navar LG. Renal endosomes contain angiotensin peptides, converting enzyme, and AT1A receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 277: F303–F311, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ingelfinger JR, Jung F, Diamant D, Haveran L, Lee E, Brem A, Tang SS. Rat proximal tubule cell line transformed with origin-defective SV40 DNA: autocrine ANG II feedback. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 276: F218–F227, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ito M, Oliverio MI, Mannon PJ, Best CF, Maeda N, Smithies O, Coffman TM. Regulation of blood pressure by the type 1A angiotensin II receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 3521–3525, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Jan Danser AH, Saris JJ. Prorenin uptake in the heart: a prerequisite for local angiotensin generation? J Mol Cell Cardiol 34: 1463–1472, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Johnson RJ, Alpers CE, Yoshimura A, Lombardi D, Pritzl P, Floege J, Schwartz SM. Renal injury from angiotensin II-mediated hypertension. Hypertension 19: 464–474, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Johnston CI. Franz Volhard Lecture. Renin-angiotensin system: a dual tissue and hormonal system for cardiovascular control. J Hypertens Suppl 10: S13–S26, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kimbrough HM, Jr, Vaughan ED, Jr, Carey RM, Ayers CR. Effect of intrarenal angiotensin II blockade on renal function in conscious dogs. Circ Res 40: 174–178, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kobori H, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Enhancement of angiotensinogen expression in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension 37: 1329–1335, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kobori H, Nangaku M, Navar LG, Nishiyama A. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: from physiology to the pathobiology of hypertension and kidney disease. Pharmacol Rev 59: 251–287, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kumar R, Singh VP, Baker KM. The intracellular renin-angiotensin system: a new paradigm. Trends Endocrinol Metab 18: 208–214, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kumar R, Singh VP, Baker KM. The intracellular renin-angiotensin system: implications in cardiovascular remodeling. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 17: 168–173, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74a. Kumar R, Yong QC, Thomas CM, Baker KM. Intracardiac intracellular angiotensin system in diabetes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol (December 14, 2011). doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00512.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lavoie JL, Liu X, Bianco RA, Beltz TG, Johnson AK, Sigmund CD. Evidence supporting a functional role for intracellular renin in the brain. Hypertension 47: 461–466, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lavoie JL, Sigmund CD. Minireview: overview of the renin-angiotensin system—an endocrine and paracrine system. Endocrinology 144: 2179–2183, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Le TH, Coffman TM. Targeting genes in the renin-angiotensin system. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 17: 57–63, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Levens NR, Freedlender AE, Peach MJ, Carey RM. Control of renal function by intrarenal angiotensin II. Endocrinology 112: 43–49, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Levens NR, Peach MJ, Carey RM. Role of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in the control of renal function. Circ Res 48: 157–167, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Li XC, Campbell DJ, Ohishi M, Yuan S, Zhuo JL. AT1 receptor-activated signaling mediates angiotensin IV-induced renal cortical vasoconstriction in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1024–F1033, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Li XC, Carretero OA, Navar LG, Zhuo JL. AT1 receptor-mediated accumulation of extracellular angiotensin II in proximal tubule cells: role of cytoskeleton microtubules and tyrosine phosphatases. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F375–F383, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Li XC, Widdop RE. AT2 receptor-mediated vasodilatation is unmasked by AT1 receptor blockade in conscious SHR. Br J Pharmacol 142: 821–830, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Li XC, Cook JL, Rubera I, Tauc M, Zhang F, Zhuo JL. Intrarenal transfer of an intracellular cyan fluorescent fusion of angiotensin II selectively in proximal tubules increases blood pressure in rats and mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F1076–F1088, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Li XC, Hopfer U, Zhuo JL. AT1 receptor-mediated uptake of angiotensin II and NHE-3 expression in proximal tubule cells through the microtubule-dependent endocytic pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F1342–F1352, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Li XC, Navar LG, Shao Y, Zhuo JL. Genetic deletion of AT1a receptors attenuates intracellular accumulation of angiotensin II in the kidney of AT1a receptor-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F586–F593, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Li XC, Zhuo JL. Selective knockdown of AT1 receptors by RNA interference inhibits Val5-Ang II endocytosis and NHE-3 expression in immortalized rabbit proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C367–C378, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Li XC, Zhuo JL. In vivo regulation of AT1a receptor-mediated intracellular uptake of [125I]-Val5-angiotensin II in the kidneys and adrenal glands of AT1a receptor-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F293–F302, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Li XC, Zhuo JL. Intracellular ANG II directly induces in vitro transcription of TGF-β1, MCP-1, and NHE-3 mRNAs in isolated rat renal cortical nuclei via activation of nuclear AT1a receptors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C1034–C1045, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Li XC, Zhuo JL. Nuclear factor-κB as a hormonal intracellular signaling molecule: focus on angiotensin II-induced cardiovascular and renal injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 17: 37–43, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Li XC, Zhuo JL. Phosphoproteomic analysis of AT1 receptor-mediated signaling responses in proximal tubules of angiotensin II-induced hypertensive rats. Kidney Int 80: 620–632, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Luft FC. Proinflammatory effects of angiotensin II and endothelin: targets for progression of cardiovascular and renal diseases. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 11: 59–66, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Luttrell LM, Gesty-Palmer D. Beyond desensitization: physiological relevance of arrestin-dependent signaling. Pharmacol Rev 62: 305–330, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C82–C97, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Mendelsohn FA. Angiotensin II: evidence for its role as an intrarenal hormone. Kidney Int Suppl 12: S78–S81, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Mor A, Philips MR. Compartmentalized Ras/MAPK signaling. Annu Rev Immunol 24: 771–800, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Morinelli TA, Raymond JR, Baldys A, Yang Q, Lee MH, Luttrell L, Ullian ME. Identification of a putative nuclear localization sequence within the angiotensin II AT1A receptor associated with nuclear activation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C1398–C1408, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Murphy JE, Padilla BE, Hasdemir B, Cottrell GS, Bunnett NW. Endosomes: A legitimate platform for the signaling train. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 1–8, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Murphy TJ, Alexander RW, Griendling KK, Runge MS, Bernstein KE. Isolation of a cDNA encoding the vascular type-1 angiotensin II receptor. Nature 351: 233–236, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Navar LG, Carmines PK, Huang WC, Mitchell KD. The tubular effects of angiotensin II. Kidney Int Suppl 20: S81–S88, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Navar LG, Harrison-Bernard LM, Wang CT, Cervenka L, Mitchell KD. Concentrations and actions of intraluminal angiotensin II. J Am Soc Nephrol 10 Suppl 11: S189–S195, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Navar LG, Imig JD, Zou L, Wang CT. Intrarenal production of angiotensin II. Semin Nephrol 17: 412–422, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Navar LG, Inscho EW, Majid SA, Imig JD, Harrison-Bernard LM, Mitchell KD. Paracrine regulation of the renal microcirculation. Physiol Rev 76: 425–536, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Navar LG, Kobori H, Prieto MC, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA. Intratubular renin-angiotensin system in hypertension. Hypertension 57: 355–362, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Navar LG, Prieto MC, Satou R, Kobori H. Intrarenal angiotensin II and its contribution to the genesis of chronic hypertension. Curr Opin Pharmacol 11: 180–186, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Navar LG, Rosivall L. Contribution of the renin-angiotensin system to the control of intrarenal hemodynamics. Kidney Int 25: 857–868, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Nishiyama A, Seth DM, Navar LG. Renal interstitial fluid concentrations of angiotensins I and II in anesthetized rats. Hypertension 39: 129–134, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Orlowski J. Heterologous expression and functional properties of amiloride high affinity (NHE-1) and low affinity (NHE-3) isoforms of the rat Na/H exchanger. J Biol Chem 268: 16369–16377, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Ozawa Y, Kobori H. Crucial role of Rho-nuclear factor-κB axis in angiotensin II-induced renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F100–F109, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Ozono R, Wang ZQ, Moore AF, Inagami T, Siragy HM, Carey RM. Expression of the subtype 2 angiotensin (AT2) receptor protein in rat kidney. Hypertension 30: 1238–1246, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Padia SH, Howell NL, Kemp BA, Fournie-Zaluski MC, Roques BP, Carey RM. Intrarenal aminopeptidase N inhibition restores defective angiontesin II type 2-mediated natriuresis in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 55: 474–480, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Padia SH, Howell NL, Siragy HM, Carey RM. Renal angiotensin type 2 receptors mediate natriuresis via angiotensin III in the angiotensin II type 1 receptor-blocked rat. Hypertension 47: 537–544, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Padia SH, Kemp BA, Howell NL, Gildea JJ, Keller SR, Carey RM. Intrarenal angiotensin III infusion induces natriuresis and angiotensin type 2 receptor translocation in Wistar-Kyoto but not in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 53: 338–343, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Padia SH, Kemp BA, Howell NL, Siragy HM, Fournie-Zaluski MC, Roques BP, Carey RM. Intrarenal aminopeptidase N inhibition augments natriuretic responses to angiotensin III in angiotensin type 1 receptor-blocked rats. Hypertension 49: 625–630, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Park S, Bivona BJ, Kobori H, Seth DM, Chappell MC, Lazartigues E, Harrison-Bernard LM. Major role for ACE-independent intrarenal ANG II formation in type II diabetes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F37–F48, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Paul M, Poyan MA, Kreutz R. Physiology of local renin-angiotensin systems. Physiol Rev 86: 747–803, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Pendergrass KD, Averill DB, Ferrario CM, Diz DI, Chappell MC. Differential expression of nuclear AT1 receptors and angiotensin II within the kidney of the male congenic mRen2 Lewis rat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1497–F1506, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Peters J, Farrenkopf R, Clausmeyer S, Zimmer J, Kantachuvesiri S, Sharp MG, Mullins JJ. Functional significance of prorenin internalization in the rat heart. Circ Res 90: 1135–1141, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Ploth DW, Navar LG. Intrarenal effects of the renin-angiotensin system. Fed Proc 38: 2280–2285, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Pohl M, Kaminski H, Castrop H, Bader M, Himmerkus N, Bleich M, Bachmann S, Theilig F. Intrarenal renin angiotensin system revisited: role of megalin-dependent endocytosis along the proximal nephron. J Biol Chem 285: 41935–41946, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Queiroz-Leite GD, Peruzzetto MC, Neri EA, Reboucas NA. Transcriptional regulation of the Na/H exchanger NHE3 by chronic exposure to angiotensin II in renal epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 409: 470–476, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Re RN. On the biological actions of intracellular angiotensin. Hypertension 35: 1189–1190, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Re RN. Lysosomal action of intracrine angiotensin II. focus on “Intracellular angiotensin II activates rat myometrium”. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 301: C553–C554, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Re RN. Implications of intracrine hormone action for physiology and medicine. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H751–H757, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Re RN. Intracellular renin and the nature of intracrine enzymes. Hypertension 42: 117–122, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Re RN, Cook JL. The mitochondrial component of intracrine action. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H577–H583, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Re RN, Vizard DL, Brown J, LeGros L, Bryan SE. Angiotensin II receptors in chromatin. J Hypertens Suppl 2: S271–S273, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Redding KM, Chen BL, Singh A, Re RN, Navar LG, Seth DM, Sigmund CD, Tang WW, Cook JL. Transgenic mice expressing an intracellular fluorescent fusion of angiotensin II demonstrate renal thrombotic microangiopathy and elevated blood pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H1807–H1818, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Robertson A, Khairallah P. Angiotensin II: rapid localization in nuclei of smooth and cardiac muscle. Science 172: 1138–1139, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]