In South Asia, cricket has come to bear the promise of delivering lasting peace to a region tormented by a half century of strife. It may seem flippant to suggest that a sport will accomplish this when almost all else has failed, but consider the following. Mounting enmity between India and Pakistan is threatening to devour the entire region. Decades of failed diplomacy testify to the futility of conventional peace moves, and intransigent foreign policy positions bring the two neighbours ever closer to a nuclear flashpoint. India and Pakistan may speak the same language, but their deadlock cries out for a new medium of communication.

Like marmalade, tweed jackets, and other things English, cricket is an acquired taste, which makes it slow to pick up but impossible to let go of. Introduced to the subcontinent in the 1800s, by the 1920s it was commanding great popularity in colonial India. In 1932 India became a Test playing country and, five years after the partition of 1947, Pakistan followed suit. In a cheerless, gloomy existence towards the bottom end of health and economic indices, the two nations found joy in cricket. It is easy to see why. Cricket provided a global forum for Pakistan and India to demonstrate talent and spirit, and defeat more advanced nations, such as England and Australia. Naturally enough, it cast a spell on the masses, became the embodiment of national self esteem, and turned cricket players into icons and celebrities.

Cricket has suddenly acquired huge public health significance in South Asia

A sport followed and played with equally fervent passion on both sides of the border has the power to be an instrument of peace, but it can also backfire, often quite unpredictably. For either country, a cricket loss to the neighbour can play havoc with national morale. Ruling party officials in India have expressed concern that a poor cricket showing in Pakistan might cost them the national election. In Pakistan, after India snapped cricket ties in the wake of the Kargil incursion of 1999, the mood turned sombre and national frustration began to crescendo. It is a testimony to the hold of cricket on the subcontinent that it took the restoration of cricketing links in the form of the 2003-4 series in Pakistan for the peoples of both countries to be finally convinced that the current thaw in relations was genuine.

Cricket's South Asian legions are not limited to India and Pakistan. In 1981 Sri Lanka became a Test playing country and, in 2000, so did Bangladesh. The sport has also made great strides in Nepal, which recently stunned South Africa with a shock defeat in the junior world cup.

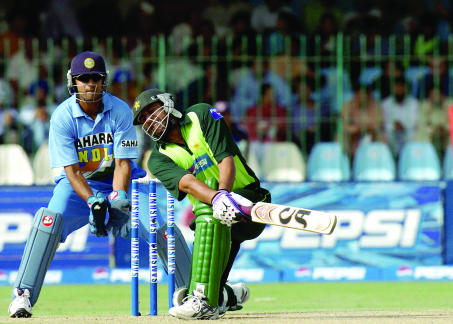

Figure 1.

Can cricket serve peace? Inzamum-ul-Haq sweeps as Rahul Dravid watches. India are touring Pakistan after 14 years

Credit: JEWEL SAMAD/AFP/GETTY

Few other pastimes embody fair play and respect for law so completely. Cricket is emerging as the one universal language of South Asia that could be a foolproof basis for finding common ground in other areas of life.

With the power to promote peace and, therefore, the health and wellbeing of hundreds of millions, cricket has suddenly acquired huge public health significance in South Asia. But for cricket to heal the gaping wound between India and Pakistan, we're going to need lots of it. The homoeopathic doses administered thus far—a mere 12 Test series over 52 years during which sporting ties were suspended over half the time—simply will not do. Above all else, the mammoth South Asian fan base needs to start seeing cricket as a pursuit of shared enjoyment, not as a calculus of honour and shame. This is bound to happen as the two countries play each other more and more. No one understands this better than Indian and Pakistani cricketers themselves, who have always got along famously.

Recently, as if to answer sceptics who said that cricket cannot serve peace, India and Pakistan played a match in Karachi. A largely Pakistani crowd exceeding 30 000 cheered the Indian team on to the field with a deafening roar. In 1987 Pakistani president Zia ul Haq had seized the diplomatic initiative by turning up at an India-Pakistan test match in Jaipur. This time in Karachi it was Priyanka Gandhi, Congress Party hope and heir-apparent to the Nehru dynasty, who made a splash that won her instant celebrity in Pakistan and may have wrong-footed India's ruling BJP. Even Colin Powell became a believer. “It's fascinating what sports can do,” he was quoted as saying shortly afterwards.

Cricket cannot solve the conundrum of Kashmir. But it can bring both parties to the table

Of course, cricket cannot do everything. It cannot, for example, solve the territorial conundrum of Kashmir that is at the heart of the India-Pakistan conflict. But cricket can bring both parties to the table. If negotiations stall, cricketspeak can restore the channels of communication. Can't agree on the Chenab formula or the fate of the valley? Why not take a break and discuss Sachin Tendulkar's poetic cover drives or Shoaib Akhtar's blinding yorkers?

The British have long said that cricket is the best of games. India and Pakistan now find themselves in a position to prove it beyond a shadow of doubt.