Abstract

Epithelial tumor cells can become mesenchymal cells and vice versa via phenotypic transitions, a process known as epithelial plasticity. We postulate that during the process of metastasis, circulating tumor cells (CTCs) lose their epithelial phenotype and acquire a mesenchymal phenotype that may not be sufficiently captured by existing epithelial-based CTC technologies. We report here on the development of a novel CTC capture method, based on the biology of epithelial plasticity, which isolates cells based on OB-cadherin cell surface expression. Using this mesenchymal-based assay, OB-cadherin cellular events are detectable in men with metastatic prostate cancer and are less common in healthy volunteers. This method may complement existing epithelial-based methods and may be particularly useful in patients with bone metastases.

Keywords: Circulating tumor cells, epithelial plasticity, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, OB-cadherin, osteomimicry, prostate cancer

1. Introduction

Epithelial plasticity (EP) refers to the reversible loss of the epithelial cellular phenotype, a process known to occur during cancer metastasis. This EP biology has been linked in multiple studies to the risk of cancer metastasis and the acquisition of mesenchymal and/or stemness properties [1, 2] through a process termed epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). EMT has been linked to chemoresistance, invasion, intravasation, and dissemination in multiple preclinical models of cancer. The reverse process, mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET), which results in the re-expression of the epithelial phenotype, is also likely of great importance in development and metastasis and has been linked to metastatic colonization and survival of tumor cells in the metastatic niche [3]. In prostate cancer, evidence exists for the upregulation of mesenchymal biomarkers during androgen deprivation in prostate cancer cell lines, animal models, and in patient tumor specimens [4, 5]. Moreover, these biomarkers are plastic, revert upon replacement of testosterone, and are linked to an increased metastatic propensity and chemoresistance [5, 6]. It has been proposed that mesenchymal-like tumor cells may better promote local tumor invasion and intravasation/extravasation, but epithelial tumor cells may be necessary for eventual survival and proliferation in the metastatic niche, illustrating the potential relevance of the dual nature of EP in mediating the full process of metastasis [7, 8].

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are cells that have migrated from the primary tumor and invaded into the circulation. We postulate that during the process of metastasis, some CTCs lose their epithelial phenotype and acquire a mesenchymal phenotype that is not captured by existing epithelial-based CTC technology. There are many methods under development to capture CTCs from the blood of cancer patients. The only FDA-cleared technology is CELLSEARCH® (Janssen/Veridex), which utilizes an anti-epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) ferrofluid to capture CTCs and follows with an additional cytokeratin, CD45, and DAPI staining procedure to visualize the cells and differentiate them from leukocytes. Using CELLSEARCH®, CTCs have been shown to be rare in individuals without malignancy and present in a range of frequencies in patients with various metastatic carcinomas [9].

The paramount challenge of CTC isolation is that tumor cells are rare and exist within billions of red blood cells and millions of leukocytes. There are numerous CTC assays under development, which enrich for CTCs using a variety of methods, and these have been reviewed elsewhere [10, 11]. There are also assays under development to identify CTC-derived DNA or RNA, without specific cell-of-origin determination [12-15]. The majority of these assays utilize EpCAM or cytokeratin for enrichment or further classification, and the detection of these EpCAM- and cytokeratin-positive cellular events is known to have prognostic significance in a variety of cancer types [16-19].

Given that CTCs are extraordinarily rare relative to other circulating cells, the isolation of CTCs requires the identification and exclusion of cells expressing the pan-leukocyte marker CD45. Circulating CD45 negative cells are not necessarily tumor-derived, however, but instead may represent normal blood vessel or stromal cells, circulating mesenchymal cells or stem cells, or other host cells that exist in rare quantities in the circulation [20]. Circulating endothelial cells result from blood vessel wall turnover, and bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells may circulate in the setting of neovascularization of ischemic tissue and tumor formation. These cells are all CD45 negative and CD31 positive. Also CD45 negative but CD31 negative, mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are a more diverse group of cells that may be bone marrow-, peripheral blood-, or fat-derived [21, 22]. MSCs are multipotent cells that may differentiate into a variety of stromal cell types, circulate in inflammatory disorders, and are under active investigation for use in regenerative medicine and other conditions [23]. The significance of circulating MSCs in cancer remains unclear. Thus, any CTC detection method must distinguish tumor cells from a range of other rare non-tumor cells in the circulation that may express non-epithelial biomarkers.

There is recent evidence to suggest that CTCs with a mesenchymal phenotype are missed by CELLSEARCH® and other epithelial-based technologies [24, 25]. In patients with advanced breast and prostate cancers, we have previously demonstrated that EP biomarkers including OB-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin can be detected in CTCs that are isolated by EpCAM-based ferromagnetic capture and that co-express cytokeratin [26]. Similarly, CTCs expressing the mesenchymal markers twist and vimentin have been identified rarely in patients with early stage breast cancer but in the majority of patients with metastatic breast cancer [27], suggesting that transition to a mesenchymal phenotype may be important for metastasis. Furthermore, recent serial monitoring of CTCs with a mesenchymal phenotype, as defined by RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), suggests that there may be an association between mesenchymal CTCs and disease progression in women with breast cancer [28].

With the increasing evidence suggesting the importance of EP in metastasis, the goal of our current study is to identify CTCs that have lost their epithelial phenotype in patients with advanced prostate cancer using an innovative mesenchymal-based capture method. Such a method may complement existing epithelial-based approaches by capturing cells that have reduced or absent EpCAM expression. Antibodies directed against OB-cadherin have been attached to iron particles to form a novel ferrofluid that can replace or complement EpCAM ferrofluid in the FDA-approved CELLSEARCH® technology. An OB-cadherin-based capture method was chosen based on prior evidence of OB-cadherin expression in CTCs ([26], see Figure 1) as well as preclinical evidence that that OB-cadherin is involved in prostate cancer metastasis. OB-cadherin, also known as cadherin-11 or O-cadherin, was first identified in mouse osteoblasts [29] and is a homophilic cell adhesion molecule that mediates osteoblast adhesion during bone development [30]. Aberrant OB-cadherin expression has been recognized in breast [31], gastric [32], and prostate [33] cancers.

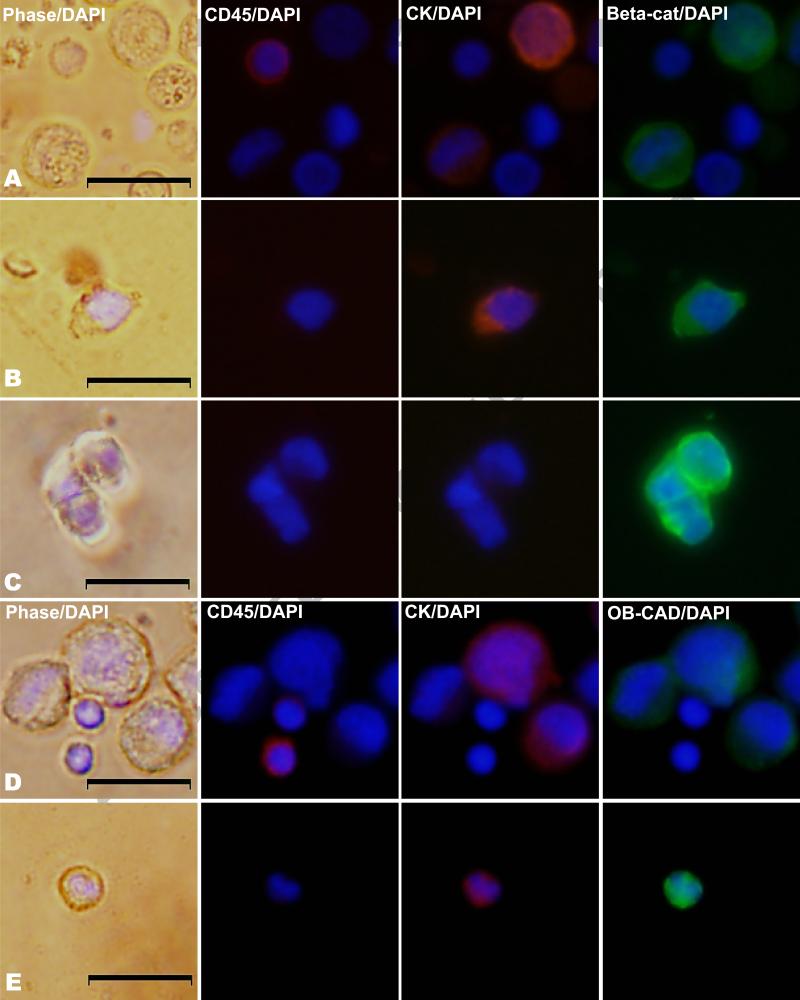

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescent images of control cells (PC-3 cells mixed with peripheral blood mononuclear cells) in rows A and D and patient-derived EpCAM-captured cells in rows B, C, and E. Cells are stained for CD45 and cytokeratin and further characterized by either β-catenin or OB-cadherin expression. Columns represent phase microscopy with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), CD45 with DAPI, Cytokeratin (CK) with DAPI, and either β-catenin (beta-cat) or OB-cadherin (OB-CAD) with DAPI. Row A shows CD45-positive control cells lacking β-catenin and CK-positive control cells expressing β-catenin. Row B shows a CTC from a man with prostate cancer with both CK and β-catenin expression, while row C shows a CD45-negative, CK-negative patient cell with β-catenin expression. Row D illustrates CD45-positive control cells lacking OB-cadherin and CK-positive control cells expressing OB-cadherin, and row E shows a CTC with both CK and OB-cadherin expression.

In human prostate cancer, examination by immunohistochemistry shows increased expression of OB-cadherin in bone metastases compared with the primary tumor [34]. Although the exact mechanism of how OB-cadherin expression facilitates bone metastasis is unclear, OB-cadherin is known to mediate adhesion between PC cells and osteoblasts [35, 36]. Preclinically, in PC-3 cells, when OB-cadherin is silenced by shRNA and the silenced cells are injected into mice, fewer bone metastases develop [34], while metastasis in other organs was unaffected. In addition, induction of OB-cadherin expression has been linked to EP biology in other model systems [37, 38]. Furthermore, androgen depletion leads to OB-cadherin upregulation, suggesting a role for OB-cadherin in castration-resistant disease progression [39]. Finally, given that lethal metastatic prostate cancer invariably spreads to bone in the vast majority of men [40], we hypothesized that OB-cadherin positive CTCs would be commonly detectable in the blood of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).

After OB-cadherin expressing cells are enriched from whole blood immunomagnetically, an additional characterization step must follow to ensure that the captured cells are the cells of interest. It has been shown that cytokeratin-expressing cancer cells lose their cytokeratin expression after undergoing epithelial-mesenchymal transition, with up to 20% of cells having no detectable cytokeratin [41]. Therefore, a protein other than cytokeratin is necessary to identify a pure mesenchymal CTC, and in the assay described here, β-catenin replaces cytokeratin as a potentially EMT-independent characterization protein.

β-catenin has multiple functions in cancer cells, including cadherin-mediated cell adhesion and involvement in the Wnt signaling pathway. When Wnt ligands are absent, β-catenin is phosphorylated and degraded. When Wnt ligands are present, β-catenin moves to the nucleus and activates target genes linked to EMT/invasion, proliferation, and survival in multiple cancers [42]. In prostate cancer, β-catenin may act as cofactor with the androgen receptor [43], and increased expression and change in localization has been observed in advanced disease [44, 45]. Thus, we also hypothesize that β-catenin expression would be a constant finding regardless of the epithelial or mesenchymal phenotypic nature of a CTC.

Metastatic tumor cells may exist as a spectrum of epithelial to mesenchymal phenotypes, and more mesenchymal phenotypes may not be sufficiently captured with existing EpCAM-based CTC technologies. We report here on the development of a novel CTC capture method, based on the biology of epithelial plasticity, which isolates cells based on OB-cadherin cell surface expression. The development of this method is a collaborative effort between Duke Cancer Institute scientists and Veridex/Janssen researchers as an academic-industry partnership. This method, if successful, may complement existing EpCAM-based methods and may be useful specifically in patients with bone metastases.

2. Description of the method

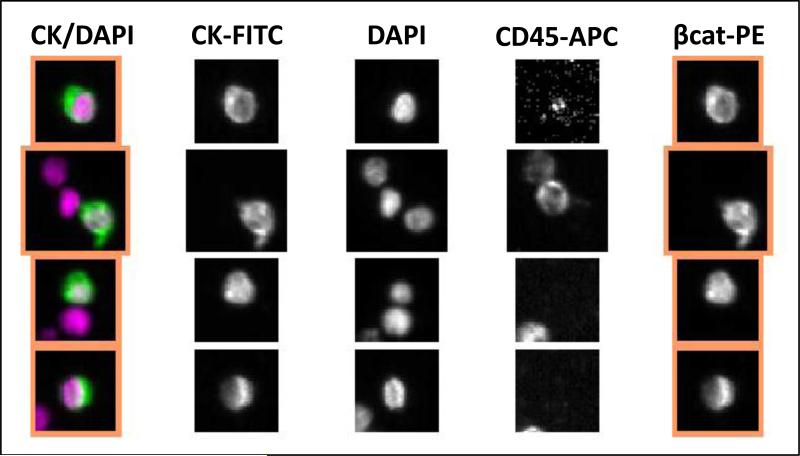

For cell capture, several antibodies against the extracellular domain of OB-cadherin were tested using positive (PC3) and negative cell lines (LNCaP) and analyzed by flow cytometry. The antibody with the highest mean fluorescent intensity in the PC3 cells and minimum background with LNCaP cells was selected for the conjugation to magnetic particles. This anti-OB-cadherin antibody (clone 283416 from R&D Systems) was conjugated to magnetic particles using procedures similar to those used for the standard anti-EPCAM ferrofluid used in CELLSEARCH® CTC assay [9]. After ferromagnetic antibody capture using OB-cadherin, cells were stained with β-catenin, CD45, and DAPI for visualization. A CTC using this novel approach was defined as a β-catenin positive, CD45 negative, nucleated intact cell, based on our preliminary data that beta-catenin can be visualized in tumor cells but not in leukocytes, as illustrated in Figure 1. Furthermore, using standard EpCAM CTC capture and identification by cytokeratin expression in the CELLSEARCH® platform, β-catenin expression on the same cells can be assessed by including a β-catenin marker in the 4th channel. In three men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, 67% (range 0.47-0.80) of EpCAM-captured CTCs (median 53 CTCs) stained for β-catenin, with representative images shown in Figure 2 [46].

Figure 2.

Examples of β-catenin expression in EpCAM-captured CTCs from a man with castration-resistant prostate cancer. The CTCs are DAPI and CK-positive and CD45-negative. Three leukocytes are also seen (DAPI and CD45-positive) that do not have β-catenin expression.

Using the OB-cadherin antibody ferrofluid to capture cells and beta-catenin expression, lack of CD45 expression, and positive nuclear DAPI staining to characterize the cells, we have developed an assay to identify a novel mesenchymal CTC phenotype. This mesenchymal capture kit was used with the CELLSEARCH® platform (Veridex LLC), including the AUTOPREP for sample preparation and the CELLTRACKS ANALYZER II for analysis of the captured cells [9]. The mesenchymal cell capture kit included ferrofluid coated with anti-OB-cadherin antibodies to immunomagnetically enrich mesenchymal cells; a phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibody that binds to β-catenin (clone L54E2 from Cell Signaling); an antibody to CD45 conjugated to allophycocyanin (APC); nuclear dye 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to fluorescently label the cells; and buffers to wash, permeabilize, and resuspend the cells. Because the OB-cadherin antigen was demonstrated to be unstable in CellSave preservative tubes, blood was collected in EDTA tubes and processed within 8 hours of collection. Briefly, 7.5 mL EDTA blood was mixed with 6.5 mL of dilution buffer, centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 minutes, and placed on the AUTOPREP sample preparation system. After aspiration of the plasma and buffer layer by the instrument, ferrofluid was added. After the incubation period and subsequent magnetic separation, unbound cells and remaining plasma were aspirated. The staining reagents were then added, along with a permeabilization buffer, to fluorescently label the immunomagnetically enriched cells. After incubation on the system, the magnetic separation was repeated, and excess staining reagents were aspirated. In the final processing step, the cells were resuspended in the MagNest device, which consists of a chamber and two magnets that orient the immunomagnetically labeled cells for analysis using the CELLTRACKS ANALYZER II.

For analysis, the MagNest was placed on the CELLTRACKS ANALYZER II, a four-color semi-automated fluorescence microscope. Image frames covering the entire surface of the cartridge for each of the fluorescent filter cubes were captured. The captured images containing objects that meet pre-specified criteria (DAPI and PE positivity in same frame) were automatically presented in a web-enabled browser, from which final selection of cells must be made by the operator. The criteria for an object to be defined as a mesenchymal CTC (designated as “events”) include an intact cell greater than 4 µm with a visible nucleus (DAPI positive), positive staining for β-catenin-PE, and negative staining for CD45-APC, as shown in Figure 3. Results of cell enumeration are expressed as the number of cells per 7.5 mL of blood.

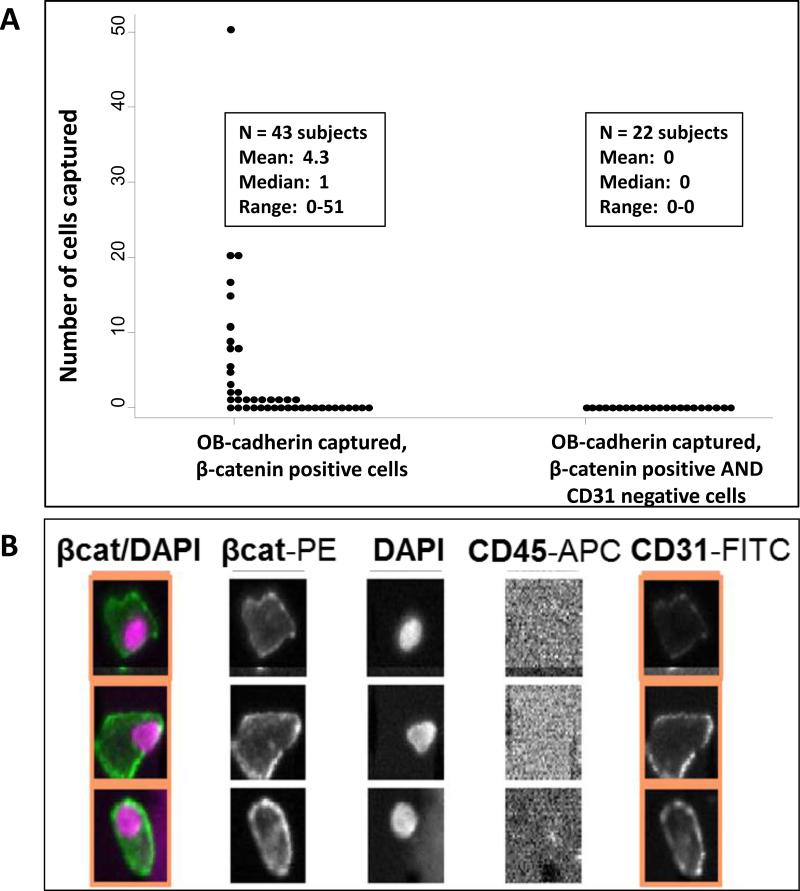

Figure 3.

After enrichment using anti-OB-cadherin ferrofluid, mesenchymal CTCs are differentiated from leukocytes by the presence of β-catenin expression and the lack of CD45 expression.

To summarize, OB-cadherin capture of cellular events is performed as follows

Blood is collected in EDTA tubes and processed within 8 hours of collection.

7.5 mL EDTA blood is mixed with 6.5 mL of dilution buffer, centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 minutes, and placed on the CELLSEARCH® AUTOPREP automated sample preparation system loaded with the mesenchymal cell capture kit. This kit includes ferrofluid coated with anti-OB-cadherin antibodies to immunomagnetically enrich mesenchymal cells; a PE-conjugated antibody that binds to β-catenin, an antibody to CD45 conjugated to APC, and nuclear dye DAPI to fluorescently label the cells; and buffers to wash, permeabilize, and resuspend the cells.

After aspiration of the plasma and buffer layer by the instrument, ferrofluid is added. After the incubation period and subsequent magnetic separation, unbound cells and remaining plasma are aspirated.

The staining reagents are then added, along with a permeabilization buffer, to fluorescently label the immunomagnetically enriched cells. After incubation on the system, the magnetic separation is repeated, and excess staining reagents aspirated.

Remaining cells are then resuspended in the MagNest device.

For analysis, the MagNest is placed on the CELLTRACKS ANALYZER II, a four-color semi-automated fluorescence microscope. Image frames covering the entire surface of the cartridge for each of the fluorescent filter cubes are captured. The captured images containing objects with DAPI and PE positivity in same frame are automatically presented in a web-enabled browser, from which final selection of cells is made by the operator.

The criteria for an object to be defined as a mesenchymal CTC include an intact cell greater than 4 µm captured with anti-OB-cadherin ferrofluid, with a visible nucleus (DAPI positive), positive staining for β-catenin-PE, and negative staining for CD45-APC. Results of cell enumeration are expressed as the number of cells per 7.5 mL of blood.

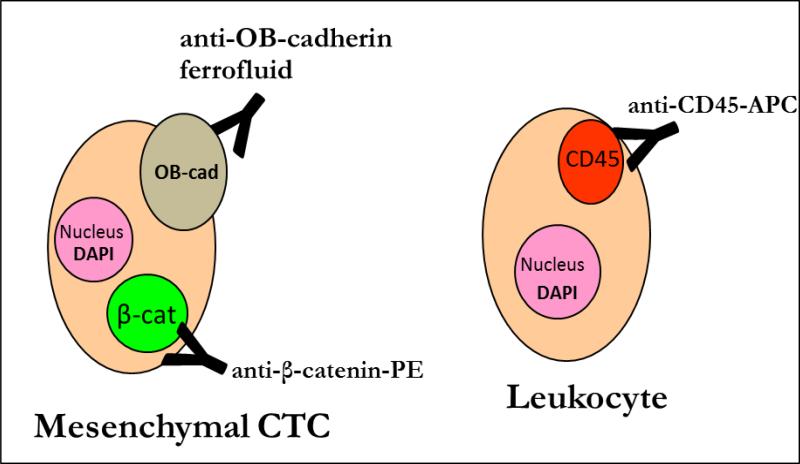

To determine that circulating mesenchymal-like tumor cells meeting the above criteria are not present in healthy individuals, blood was drawn from healthy adults age >18 into 10 mL EDTA tubes. Subjects were not eligible if they had any chronic medical condition requiring medication or a history of cancer. Samples were processed as described above within 8 hours of blood collection. All subjects were enrolled using an institutional review board-approved protocol and provided informed consent, and a total of 43 subjects were enrolled. Rare OB-cadherin-captured, β-catenin-positive events were detected in healthy volunteers. The rare events detected in healthy volunteers were stained with the endothelial marker CD31 (BD Biosciences, clone WM59) for further characterization [47]. In the 22 healthy volunteers where CD31 status was assessed, 10 subjects had detectable β-catenin-positive events (median 0, range 0-20). All detected events to date in healthy volunteers in which CD31 was assessed were CD31-positive and likely represent endothelial cells [48]. Some examples of these OB-cadherin captured, β-catenin- and CD31-positive events are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

(A) The distribution of OB-cadherin-captured, β-catenin-positive events from healthy volunteers based on CD31 status. In the 22 healthy volunteers where CD31 status was assessed, 10 subjects had detectable β-catenin-positive events (median 0, range 0-20). All events in which CD31 was assessed were CD31-positive.

(B) Examples of CD31+ cellular events detected in healthy volunteers.

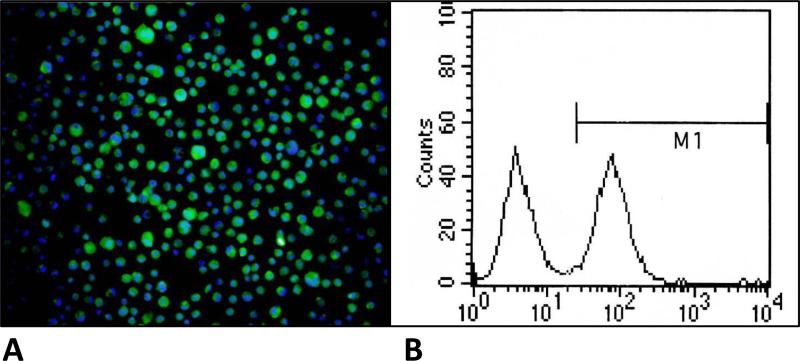

To verify that the novel mesenchymal capture assay can isolate and detect the cells of interest, spiking studies of positive and negative control cells were performed. Preliminary data investigating OB-cadherin expression on the prostate cancer PC-3 cell line revealed OB-cadherin expression on approximately 40-50% of PC-3 cells by both immunofluorescence and flow cytometry, as shown in Figure 5. The prostate cancer cell line PC-3 was cultured in flasks containing DMEM high-glucose supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and subsequently harvested using cell dissociation buffer (Gibco 13150-016) per package insert. Cells were counted on a hemocytometer and either 500 or 1,000 cells were spiked into 7.5 mL of blood obtained from healthy volunteers as described above. A median of 31.4% (range 16.1-103.4, n=13 replicates) of spiked cells were recovered using OB-cadherin capture and characterization as β-catenin-positive, CD45-negative cells as above. PC-3 cells have variable OB-cadherin expression, as illustrated in Figure 5, therefore the expected recovery of spiked PC-3 cells using OB-cadherin capture was approximately 50%.

Figure 5.

(A) Immunofluorescent images of PC-3 cells stained for OB-cadherin (green) and DAPI/nucleus (blue), illustrating that PC-3 cells are somewhat heterogeneous for OB-cadherin expression.

(B) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting of PC-3 cells based on OB-cadherin expression shows that approximately 50% of the cells express OB-cadherin.

After establishing a threshold for detection in healthy volunteers (zero OB-cadherin, β-catenin- positive cells if CD31 is included as an additional characterization marker), we next began to determine the prevalence of these cellular events in men with progressive, metastatic CRPC enrolled in a correlative clinical blood-drawing study prior to initiating a new systemic therapy. This population is largely composed of men with bone metastases (>90%) and will thus be theoretically enriched for OB-cadherin positive cells, if present. After informed consent is obtained, one CellSave® and two EDTA 10 mL tubes of blood are collected at baseline, at treatment cycle 3, and at progression. Blood obtained in EDTA tubes is used for OB-cadherin capture in duplicate and was processed as soon as possible, with no more than 8 hours elapsing from the time of collection. Blood obtained in CellSave® tubes is used for the standard EpCAM capture only and processed within 72 hours, per the established protocol [9]. Using the CELLSEARCH® system, circulating mesenchymal cells are captured with anti-OB-cadherin ferrofluid, then permeabilized and stained for further characterization as described above. Cells are enumerated per 7.5 mL of blood, and the mesenchymal CTC enumeration is compared with the standard EpCAM-based capture method. Any discrepancy in the scoring of events is resolved with discussion between two independent reviewers.

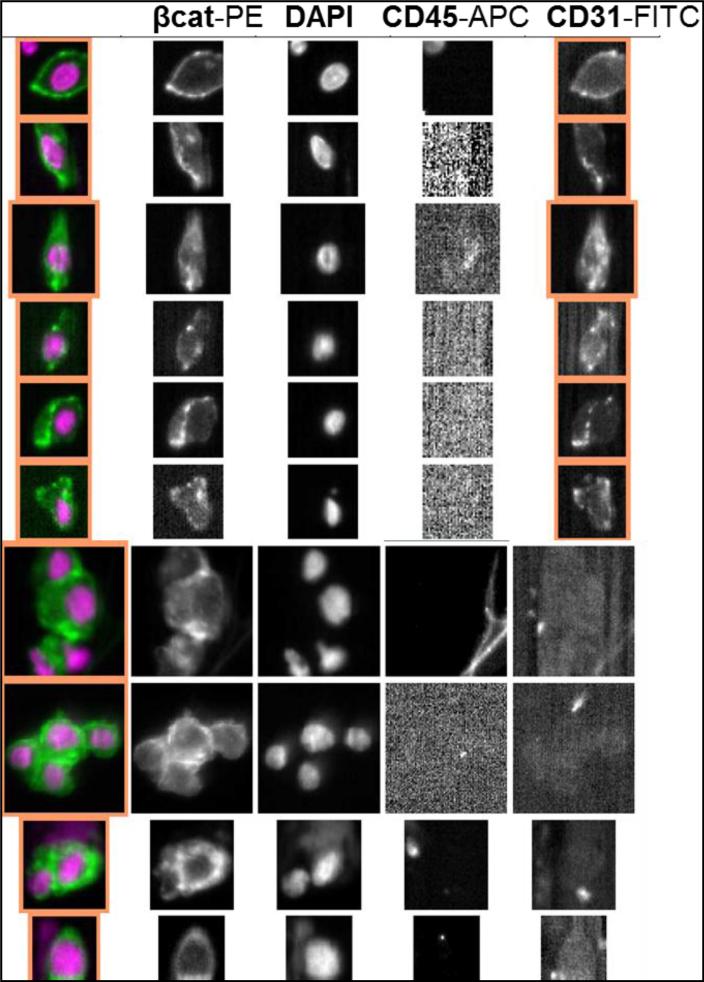

In this ongoing clinical study, the standard EpCAM-based capture assay finds more CTCs in the majority of patients, however there are exceptions in which more mesenchymal events are seen. There also appears to be more frequent sheets or clumps of cells and multiple cells per field with OB-cadherin capture than with EpCAM capture, as illustrated in Figure 6. The significance of this observation needs to be further explored, and the results of this alternative capture in CRPC patients will be reported separately, when the longitudinal data collection is complete.

Figure 6.

Examples of OB-cadherin captured, β-catenin-positive cellular events from men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. The top rows show single cells which are mostly CD31-positive and may represent endothelial cells, while the bottom rows show clumps of CD31-negative cells which may represent mesenchymal tumor cells.

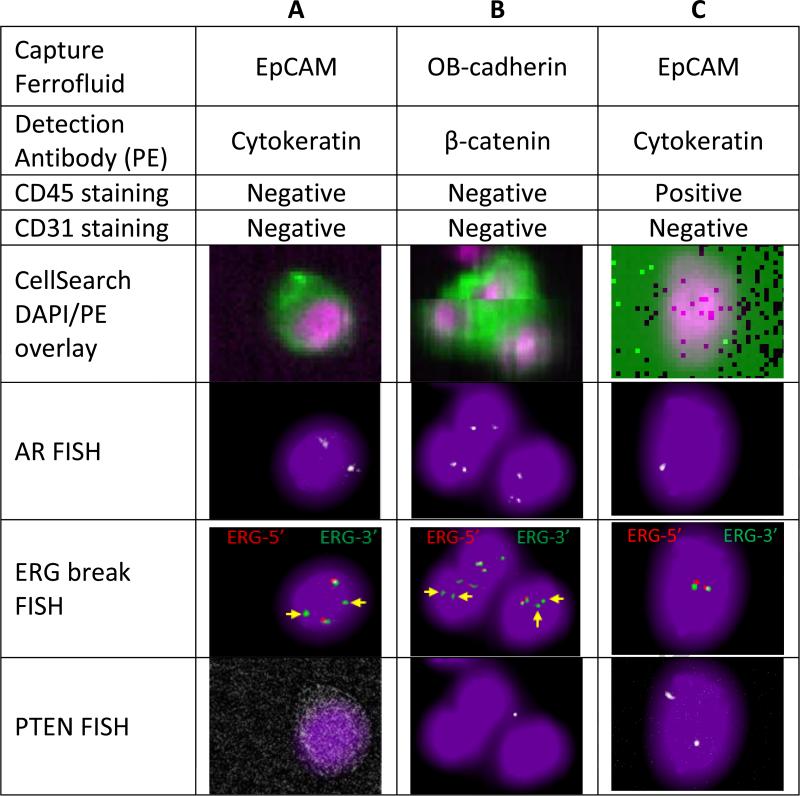

The capture of a novel CTC leaves open the possibility that these cellular events are not cancer cells, but rather host cells. For example, in healthy volunteers, the OB-cadherin-positive cells were most likely endothelial cells derived from phlebotomy and CD31-positive. In men with CRPC, these OB-cadherin-positive cells could be endothelial cells, but could also be circulating osteoblasts, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells, or other circulating mesenchymal-like cells expressing OB-cadherin. To determine the significance of OB-cadherin captured events from patients and whether these cellular events represented host cells or prostate cancer cells, DNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed for prostate cancer-specific genomic events. Cellular events were identified using the CELLTRACKS ANALYZER II as described above and then fixed using 3:1 methanol/acetic acid and dried on the cartridge as previously described [49], with the exception that the fixation device was redesigned using a programmable automated syringe pump (Cole-Parmer). This automated device ensures that the cells on the cartridge do not move and can be re-identified after FISH. Fixed and dried cartridges can be processed for FISH immediately or stored at −20°C for later use.

Using the previously described 4-color FISH assay for androgen receptor (AR) amplification, PTEN loss, and gene fusion involving the TMPRSS2-ERG locus (ERG break-apart assay) [50], the captured mesenchymal cells were evaluated for these prostate-cancer specific changes. As shown in figure 7, AR amplification, TMPRSS2-ERG fusion, and homozygous PTEN deletion was present in both EpCAM and OB-cadherin captured cells. As these genomic amplification or deletion events are unlikely to be found in normal tissues, and were also found in the EpCAM-positive cells, these findings suggest that at least some of the OB-cadherin-, beta-catenin-positive cells are prostate cancer derived and not derived from the tumor microenvironment or normal host cells. Further analysis of the prevalence of these novel cells in a broader population of men with CRPC and other tumor types will be needed to define the utility of this assay. These analyses will require a comparison with EpCAM-based approaches, particularly in men with low CTC counts despite progressive metastatic disease, to define the clinical utility of OB-cadherin-positive events. In addition, correlations of OB-cadherin-positive cellular events with clinical and pathologic characteristics and patient outcomes with systemic therapies will be needed to further define the independent role of this novel assay in the context of other prognostic biomarkers. However, these preliminary methods and early data suggest that these cells are detectable in men with CRPC, are absent in healthy volunteers, and that our methods can detect OB-cadherin positive human prostate cancer cells in blood. Further study of this method and novel mesenchymal-based capture methods are warranted.

Figure 7.

Immunostaining and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) results from a representative patient with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Columns A and B - Circulating cells captured with OB-cadherin and stained with β-catenin show same multigene FISH pattern as a CTC captured with EpCAM and stained with cytokeratin from the same patient. Androgen receptor (AR) FISH shows extra copies of the androgen receptor gene. For the ERG break FISH, yellow arrows denote missing 5’ Erg signals which is indicative of TMPRSS2:ERG fusion. PTEN FISH shows homozygous deletion of PTEN gene. To score the PTEN deletion probe, all three of the following conditions must be met: (1) zero or one PTEN signals in the CTC, (2) Clear and evaluable ERG signals in the CTC, and (3) Clear PTEN signals in nearby WBCs. Column C - leukocyte from the same patient shows a cytokeratin-negative cell with a normal FISH pattern of 1 AR signal, no ERG rearrangement, and two copies of PTEN.

3. Concluding remarks/Summary

We have described a novel assay that can be used to identify circulating mesenchymal tumor cells. The development of this assay required testing in positive-control cell lines, negative-control cell lines, healthy volunteer blood, and patient blood samples, in conjunction with CTC molecular profiling to identify tumor-specific markers. Further optimization of this assay through reliability metrics, optimization of the timing from collection to analysis, ideal preservatives for clinical use, and generalizability is in progress. Testing is currently ongoing in a Duke University IRB-approved protocol enrolling men with metastatic CRPC to evaluate the prevalence and range of these novel plastic CTCs. The common expression of OB-cadherin in CTCs would be suggestive of osteomimicry, and could provide some insight into the mechanism of prostate cancer homing to bone and the development of osteoblastic bone metastases. Correlation of these CTCs with EpCAM-positive CTCs and with clinical characteristics and outcomes is ongoing and will be reported separately. Using this novel mesenchymal-based assay, OB-cadherin and β-catenin positive cellular events are detectable in men with metastatic CRPC and are less common in healthy volunteers. OB-cadherin events in healthy volunteers uniformly express the endothelial marker CD31, whereas the CD31 status in patients with cancer is more variable, and it is likely that the process of phlebotomy can introduce CD31+ OB-cadherin positive endothelial cells. This finding is novel, and raises caution in the development of novel CTC assays, given that many normal host cells can express mesenchymal markers such as vimentin and now OB-cadherin [26]. Additional markers are required to ensure that these mesenchymal-like cells are tumor cells. Further molecular characterization, for example using FISH as described above or high- throughput RNA profiling, is necessary to determine if these mesenchymal cells are tumor-derived.

Highlights.

Epithelial plasticity is likely an important mechanism for cancer metastasis

Circulating tumor cells with mesenchymal features may be missed by standard methods

We describe a novel mesenchymal-based circulating tumor cell capture method

This approach is evaluated in healthy volunteers and men with prostate cancer

Acknowledgements

The work was supported through a joint collaborative research agreement between Duke University and Veridex/Janssen Research and Development. Additional funding for this work was supported by the Robert B. Goergen Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award (Armstrong) and a Department of Defense Physician Research Training Award (PI Armstrong, W81XWH-10-1-0483).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, Campbell LL, Polyak K, Brisken C, Yang J, Weinberg RA. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008 May 16;133:704–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kong D, Banerjee S, Ahmad A, Li Y, Wang Z, Sethi S, Sarkar FH. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition is mechanistically linked with stem cell signatures in prostate cancer cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brabletz T. To differentiate or not--routes towards metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012 Jun;12:425–36. doi: 10.1038/nrc3265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka H, Kono E, Tran CP, Miyazaki H, Yamashiro J, Shimomura T, Fazli L, Wada R, Huang J, Vessella RL, An J, Horvath S, Gleave M, Rettig MB, Wainberg ZA, Reiter RE. Monoclonal antibody targeting of N-cadherin inhibits prostate cancer growth, metastasis and castration resistance. Nat Med. 2010 Dec;16:1414–20. doi: 10.1038/nm.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun Y, Wang BE, Leong KG, Yue P, Li L, Jhunjhunwala S, Chen D, Seo K, Modrusan Z, Gao WQ, Settleman J, Johnson L. Androgen deprivation causes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the prostate: implications for androgen-deprivation therapy. Cancer Res. 2012 Jan 15;72:527–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domingo-Domenech J, Vidal SJ, Rodriguez-Bravo V, Castillo-Martin M, Quinn SA, Rodriguez-Barrueco R, Bonal DM, Charytonowicz E, Gladoun N, de la Iglesia-Vicente J, Petrylak DP, Benson MC, Silva JM, Cordon-Cardo C. Suppression of Acquired Docetaxel Resistance in Prostate Cancer through Depletion of Notch- and Hedgehog-Dependent Tumor-Initiating Cells. Cancer Cell. 2012 Sep 11;22:373–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Celia-Terrassa T, Meca-Cortes O, Mateo F, de Paz AM, Rubio N, Arnal-Estape A, Ell BJ, Bermudo R, Diaz A, Guerra-Rebollo M, Lozano JJ, Estaras C, Ulloa C, Alvarez-Simon D, Mila J, Vilella R, Paciucci R, Martinez-Balbas M, de Herreros AG, Gomis RR, Kang Y, Blanco J, Fernandez PL, Thomson TM. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition can suppress major attributes of human epithelial tumor-initiating cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012 May 1;122:1849–68. doi: 10.1172/JCI59218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai JH, Donaher JL, Murphy DA, Chau S, Yang J. Spatiotemporal regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition is essential for squamous cell carcinoma metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2012 Dec 11;22:725–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allard WJ, Matera J, Miller MC, Repollet M, Connelly MC, Rao C, Tibbe AG, Uhr JW, Terstappen LW. Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin Cancer Res. 2004 Oct 15;10:6897–904. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bednarz-Knoll N, Alix-Panabieres C, Pantel K. Clinical relevance and biology of circulating tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:228. doi: 10.1186/bcr2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu M, Stott S, Toner M, Maheswaran S, Haber DA. Circulating tumor cells: approaches to isolation and characterization. J Cell Biol. 2011 Feb 7;192:373–82. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarzenbach H, Alix-Panabieres C, Muller I, Letang N, Vendrell JP, Rebillard X, Pantel K. Cell-free tumor DNA in blood plasma as a marker for circulating tumor cells in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009 Feb 1;15:1032–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Wang CY, Yang R, Shi J, Fu R, Chen L, Klocker H, Zhang J. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR assay of prostate-specific antigen and prostate-specific membrane antigen in peripheral blood for detection of prostate cancer micrometastasis. Urol Oncol. 2008 Nov-Dec;26:634–40. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross RW, Galsky MD, Scher HI, Magidson J, Wassmann K, Lee GM, Katz L, Subudhi SK, Anand A, Fleisher M, Kantoff PW, Oh WK. A whole-blood RNA transcript-based prognostic model in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70263-2. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70263-2, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olmos D, Brewer D, Clark J, Danila DC, Parker C, Attard G, Fleisher M, Reid AH, Castro E, Sandhu SK, Barwell L, Oommen NB, Carreira S, Drake CG, Jones R, Cooper CS, Scher HI, de Bono JS. Prognostic value of blood mRNA expression signatures in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a prospective, two-stage study. Lancet Oncol. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70372-8. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70372-8, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, Stopeck A, Matera J, Miller MC, Reuben JM, Doyle GV, Allard WJ, Terstappen LW, Hayes DF. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004 Aug 19;351:781–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Bono JS, Scher HI, Montgomery RB, Parker C, Miller MC, Tissing H, Doyle GV, Terstappen LW, Pienta KJ, Raghavan D. Circulating tumor cells predict survival benefit from treatment in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008 Oct 1;14:6302–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen SJ, Punt CJ, Iannotti N, Saidman BH, Sabbath KD, Gabrail NY, Picus J, Morse M, Mitchell E, Miller MC, Doyle GV, Tissing H, Terstappen LW, Meropol NJ. Relationship of circulating tumor cells to tumor response, progression-free survival, and overall survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jul 1;26:3213–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan MS, Kirkwood A, Tsigani T, Garcia-Hernandez J, Hartley JA, Caplin ME, Meyer T. Circulating tumor cells as prognostic markers in neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Jan 20;31:365–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolonin MG, Evans KW, Mani SA, Gomer RH. Alternative origins of stroma in normal organs and disease. Stem Cell Res. 2012 Mar;8:312–23. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Daquinag A, Traktuev DO, Amaya-Manzanares F, Simmons PJ, March KL, Pasqualini R, Arap W, Kolonin MG. White adipose tissue cells are recruited by experimental tumors and promote cancer progression in mouse models. Cancer Res. 2009 Jun 15;69:5259–66. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra PJ, Glod JW, Banerjee D. Mesenchymal stem cells: flip side of the coin. Cancer Res. 2009 Feb 15;69:1255–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salem HK, Thiemermann C. Mesenchymal stromal cells: current understanding and clinical status. Stem Cells. 2010 Mar 31;28:585–96. doi: 10.1002/stem.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sieuwerts AM, Kraan J, Bolt J, van der Spoel P, Elstrodt F, Schutte M, Martens JW, Gratama JW, Sleijfer S, Foekens JA. Anti-epithelial cell adhesion molecule antibodies and the detection of circulating normal-like breast tumor cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009 Jan 7;101:61–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aktas B, Tewes M, Fehm T, Hauch S, Kimmig R, Kasimir-Bauer S. Stem cell and epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers are frequently overexpressed in circulating tumor cells of metastatic breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R46. doi: 10.1186/bcr2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong AJ, Marengo MS, Oltean S, Kemeny G, Bitting RL, Turnbull JD, Herold CI, Marcom PK, George DJ, Garcia-Blanco MA. Circulating tumor cells from patients with advanced prostate and breast cancer display both epithelial and mesenchymal markers. Mol Cancer Res. 2011 Aug;9:997–1007. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kallergi G, Papadaki MA, Politaki E, Mavroudis D, Georgoulias V, Agelaki S. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition markers expressed in circulating tumour cells of early and metastatic breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R59. doi: 10.1186/bcr2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu M, Bardia A, Wittner BS, Stott SL, Smas ME, Ting DT, Isakoff SJ, Ciciliano JC, Wells MN, Shah AM, Concannon KF, Donaldson MC, Sequist LV, Brachtel E, Sgroi D, Baselga J, Ramaswamy S, Toner M, Haber DA, Maheswaran S. Circulating breast tumor cells exhibit dynamic changes in epithelial and mesenchymal composition. Science. 2013 Feb 1;339:580–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1228522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okazaki M, Takeshita S, Kawai S, Kikuno R, Tsujimura A, Kudo A, Amann E. Molecular cloning and characterization of OB-cadherin, a new member of cadherin family expressed in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 1994 Apr 22;269:12092–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawaguchi J, Azuma Y, Hoshi K, Kii I, Takeshita S, Ohta T, Ozawa H, Takeichi M, Chisaka O, Kudo A. Targeted disruption of cadherin-11 leads to a reduction in bone density in calvaria and long bone metaphyses. J Bone Miner Res. 2001 Jul;16:1265–71. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.7.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pishvaian MJ, Feltes CM, Thompson P, Bussemakers MJ, Schalken JA, Byers SW. Cadherin-11 is expressed in invasive breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1999 Feb 15;59:947–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shibata T, Ochiai A, Gotoh M, Machinami R, Hirohashi S. Simultaneous expression of cadherin-11 in signet-ring cell carcinoma and stromal cells of diffuse-type gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 1996 Feb 6;99:147–53. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)04047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomita K, van Bokhoven A, van Leenders GJ, Ruijter ET, Jansen CF, Bussemakers MJ, Schalken JA. Cadherin switching in human prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2000 Jul 1;60:3650–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu K, Cheng CJ, Ye X, Lee YC, Zurita AJ, Chen DT, Yu-Lee LY, Zhang S, Yeh ET, Hu MC, Logothetis CJ, Lin SH. Cadherin-11 promotes the metastasis of prostate cancer cells to bone. Mol Cancer Res. 2008 Aug;6:1259–67. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang CF, Lira C, Chu K, Bilen MA, Lee YC, Ye X, Kim SM, Ortiz A, Wu FL, Logothetis CJ, Yu-Lee LY, Lin SH. Cadherin-11 increases migration and invasion of prostate cancer cells and enhances their interaction with osteoblasts. Cancer Res. 2010 Jun 1;70:4580–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamura D, Hiraga T, Myoui A, Yoshikawa H, Yoneda T. Cadherin-11-mediated interactions with bone marrow stromal/osteoblastic cells support selective colonization of breast cancer cells in bone. Int J Oncol. 2008 Jul;33:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider DJ, Wu M, Le TT, Cho SH, Brenner MB, Blackburn MR, Agarwal SK. Cadherin-11 contributes to pulmonary fibrosis: potential role in TGF-beta production and epithelial to mesenchymal transition. FASEB J. 2012 Feb;26:503–12. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-186098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farina AK, Bong YS, Feltes CM, Byers SW. Post-transcriptional regulation of cadherin-11 expression by GSK-3 and beta-catenin in prostate and breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee YC, Cheng CJ, Huang M, Bilen MA, Ye X, Navone NM, Chu K, Kao HH, Yu-Lee LY, Wang Z, Lin SH. Androgen depletion up-regulates cadherin-11 expression in prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2010 May;221:68–76. doi: 10.1002/path.2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah RB, Mehra R, Chinnaiyan AM, Shen R, Ghosh D, Zhou M, Macvicar GR, Varambally S, Harwood J, Bismar TA, Kim R, Rubin MA, Pienta KJ. Androgen-independent prostate cancer is a heterogeneous group of diseases: lessons from a rapid autopsy program. Cancer Res. 2004 Dec 15;64:9209–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pecot CV, Bischoff FZ, Mayer JA, Wong KL, Pham T, Bottsford-Miller J, Stone RL, Lin YG, Jaladurgam P, Roh JW, Goodman BW, Merritt WM, Pircher TJ, Mikolajczyk SD, Nick AM, Celestino J, Eng C, Ellis LM, Deavers MT, Sood AK. A novel platform for detection of CK+ and CK- CTCs. Cancer Discov. 2011 Dec;1:580–6. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006 Nov 3;127:469–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Truica CI, Byers S, Gelmann EP. Beta-catenin affects androgen receptor transcriptional activity and ligand specificity. Cancer Res. 2000 Sep 1;60:4709–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whitaker HC, Girling J, Warren AY, Leung H, Mills IG, Neal DE. Alterations in beta-catenin expression and localization in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2008 Aug 1;68:1196–205. doi: 10.1002/pros.20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wan X, Liu J, Lu JF, Tzelepi V, Yang J, Starbuck MW, Diao L, Wang J, Efstathiou E, Vazquez ES, Troncoso P, Maity SN, Navone NM. Activation of beta-catenin signaling in androgen receptor-negative prostate cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2012 Feb 1;18:726–36. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bitting RL, Boominathan R, Rao C, Embree E, George DJ, Connelly M, Kemeny G, Garcia-Blanco MA, Armstrong AJ. Isolation of Circulating Tumor Cells Using a Novel EMT-Based Capture Method. J Clin Oncol. 30S abstr 10533, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pusztaszeri MP, Seelentag W, Bosman FT. Immunohistochemical expression of endothelial markers CD31, CD34, von Willebrand factor, and Fli-1 in normal human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006 Apr;54:385–95. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4A6514.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Erdbruegger U, Haubitz M, Woywodt A. Circulating endothelial cells: a novel marker of endothelial damage. Clin Chim Acta. 2006 Nov;373:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swennenhuis JF, Tibbe AGJ, Levink R, Sipkema RCJ, Terstappen LWMM. Characterization of Circulating Tumor Cells by Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization. Cytometry Part A. 2009 Jun;75A:520–527. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Attard G, Swennenhuis JF, Olmos D, Reid AH, Vickers E, A'Hern R, Levink R, Coumans F, Moreira J, Riisnaes R, Oommen NB, Hawche G, Jameson C, Thompson E, Sipkema R, Carden CP, Parker C, Dearnaley D, Kaye SB, Cooper CS, Molina A, Cox ME, Terstappen LW, de Bono JS. Characterization of ERG, AR and PTEN gene status in circulating tumor cells from patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009 Apr 1;69:2912–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]