Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the association of ED with commonly used medications including antihypertensive, psychoactive medications, and pain and anti-inflammatory medications.

Subjects and Methods

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey used a multistage stratified design to recruit a random sample of 2,301 men age 30-79. ED was assessed using the 5-item International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5).

Prescription medication use, captured using a combination of drug inventory and self-report with a prompt by indication, included in this analysis were antihypertensive agents (AHT), psychoactive medications, and pain and anti-inflammatory medications.

Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios of the association of medication use and ED and adjust for potential confounders including age, comorbid conditions, and sociodemographic and lifestyle factors.

Results

Multivariable analyses show benzodiazepines (adjusted OR=2.34, 95%CI:1.03, 5.31) and tricyclic antidepressants (adjusted OR=3.35, 95%CI:1.09, 10.27) were associated with ED, while no association was observed for SSNRI/SNRIs and atypical antipsychotics.

AHT use, whether in monotherapy or in conjunction with other AHTs, and pain or anti-inflammatory medications were not associated with ED after accounting for confounding factors.

Conclusions

Results of the BACH study suggest adverse effects of some psychoactive medications (benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants).

No evidence of an association of AHT or pain and anti-inflammatory medication with ED was observed.

Keywords: erectile dysfunction, pharmacoepidemiology, epidemiology

Introduction

ED is a common disorder in aging men with estimated prevalence rates of 25-35%.[1-3] An increased risk of ED with chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and depression and associated risk factors (e.g. obesity, smoking, decreased physical activity) has been established.[2-4] Whether prescription medication use contributes to ED in addition to the effect of the illness itself remains controversial. Overall, an increase in the number of prescription medications has been associated with increased odds of ED.[5] Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) suggest that AHT and antidepressant use may increase the risk of ED.[6, 7] Studies of specific AHT classes suggest adverse effects of diuretics and beta blockers.[8] However, results are not always consistent. Results of the few studies of antidepressant or anti-inflammatory use and ED suggest increased risk of ED with tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs, and benzodiazepines as well as use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID).[6, 7, 9-11]

Previous analyses of data from BACH Survey suggest an association of lipid lowering medications with ED among younger men with diabetes or cardiovascular disease.[12] The objectives of this analysis were to investigate the association of ED with other commonly used medications: 1) antihypertensive medications, 2) psychoactive medications, and 3) pain and anti-inflammatory medications.

Subjects and Methods

Overall Design

The BACH Survey is a population-based epidemiologic survey of a broad range of urologic symptoms and risk factors in a randomly selected sample. Detailed methods have been described elsewhere.[13] In brief, BACH used a multi-stage stratified random sample to recruit approximately equal numbers of subjects according to age (30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-79 years), gender, and race and ethnic group (Black, Hispanic, and White). The baseline BACH sample was recruited from April 2002 through June 2005. Interviews were completed with 63.3% of eligible subjects, resulting in a total sample of 5,503 adults (2,301 men, 3,202 women). All protocols and informed consent procedures were approved by the New England Research Institutes' Institutional Review Board. All subjects provided written informed consent.

Data collection

Data were obtained during a 2-hour in-person interview, conducted by a trained (bilingual) interviewer, generally in the subject's home. Height, weight, hip and waist circumference were measured along with self-reported information on medical and reproductive history, major comorbidities, lifestyle and psychosocial factors, and symptoms of urologic conditions. Two blood pressure measurements were obtained 2 minutes apart and were averaged.

Erectile Dysfunction

Erectile Dysfunction (ED) was defined using the 5 item International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5), a self-administered and validated instrument.[14] The five items assess erection confidence, erection firmness, maintenance ability, maintenance frequency, and satisfaction. Each item is scored on a five-point ordinal scale where lower values represent poorer sexual function. The IIEF-5 score ranges between 5 and 25 with lower scores indicating increased severity of ED. ED was defined as a dichotomous variable using a cutoff of IIEF-5 <17 (mild to moderate, moderate, and severe).

Medications

Use of prescription medications in the past month was collected using a combination of self-report with a prompt by indication and drug inventory by direct observation/recording of medication labels by the interviewer. In the first process, participants were asked if they had taken any prescription drugs in the last 4 weeks for 14 indications (e.g., “In the last four weeks, have you been taking blood pressure or fluid pills?”) In the second process, participants were asked to gather containers for all medications used in the past 4 weeks. Medication labels were coded using the Slone Drug Dictionary, which classifies medications using a modification of the American Hospital Formulary Service Drug Pharmacologic Therapeutic Classification System.[15] Medications in this analysis include antihypertensive agents (AHTs), commonly-used psychoactive medications, and pain/anti-inflammatory medications.

Antihypertensive agents. Classes of AHT included were beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics, calcium channel blockers (CCBs), loop diuretics, angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB)-type AHTs, miscellaneous diuretics, and other AHTs (not otherwise classified). Any AHT use and number of AHT used were also included. Because of substantial overlap in use of the different AHT classes, we created a four-level variable of mutually exclusive exposure groups: 1) the class of interest in monotherapy, 2) the class of interest with other AHTs, 3) the use of any other AHT classes, and 4) no AHT use (referent).

Psychoactive medications included were: serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) grouped together (SSRI/SNRI), tricyclic antidepressants, atypical antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines.

Pain/anti-inflammatory medication classes (considered separately) include narcotic analgesics, cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) inhibitors, and aspirin-containing and ibuprofen-containing medications.

Covariates

Self-reported race/ethnicity was defined as black, Hispanic, or white. Body mass index (BMI) was categorized as <25.0, 25.0-29.9, and ≥30.0 kg/m2. Physical activity was measured using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) and was categorized as low (<100), medium (100-250), and high (>250).[16] Alcohol consumption was defined as alcoholic drinks including beer, wine and hard liquor consumed per day: 0, <1, 1-2.9, ≥3 drinks per day. Smoking was defined as never smokers, former smokers, and current smoker. Socioeconomic status (SES) index was calculated using a combination of education and household income.[17] SES was categorized as low (lower 25% of the distribution of the SES index), middle (middle 50% of the distribution), and high (upper 25% of the distribution). The presence of comorbidities (heart disease, diabetes, arthritis) was defined as a yes response to “Have you ever been told by a health care provider that you have or had….”? Heart disease was defined by self-report of myocardial infarction, angina, congestive heart failure, coronary artery bypass, or angioplasty stent. Participants reporting five or more depressive symptoms (out of 8) using the abbreviated Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression (CES-D) scale were considered to have clinically significant depression.[18]

Analytic sample

Given the importance of separating the underlying influence of hypertension with the potential influence of its treatment, a recommended strategy to control for ‘confounding by indication’ among AHT users was used.[19]Confounding by indication results from the imbalance in the underlying ED risk profile between those with hypertension and those without. Restricting analyses to men with an indication for AHT treatment reduces this imbalance and the likelihood of residual confounding. Analyses of the association of AHT medications and ED were restricted to those with evidence of AHT indications, defined in our data as any of the following: 1) measured hypertension, 2) self-report of ever diagnosis of high blood pressure with current treatment or no treatment, 3) history of myocardial infarction, angina, congestive heart failure, or 4) current AHT use. A total of 862 men (37.5%) met these criteria and were included in the analyses of AHT medications and ED.

As it was not practical to define an indication group for either psychoactive medications (used variously for anxiety, depression and other indications) or pain/anti-inflammatory medications, the total sample 2,301 men was used for these analyses with adjustment for comorbid conditions, including depression and arthritis, in multivariable analyses.

Statistical analysis

The association of prescription medications and ED was assessed using logistic regression with ED defined as IIEF-5 scores<17. Unadjusted and confounder-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) are presented. Covariates were backwards selected from a full model to be included in parsimonious (reduced) models if their overall significance was p<0.05 or if they changed the OR of associations of interest by >15%. Multiple imputation was used to obtain plausible values for missing data.[20] The proportion with missing data was <2% for all variables except for SES. The SES index was missing for 6.1% of participants (n = 333) primarily because of missing data on household income rather than years of education (0.3%, n = 16). Overall, 7.7% of BACH participants had missing data on at least one of these variables. Analyses for AHT medications conducted in the subgroup of 863 with an indication for AHT were unweighted. Analyses of the psychoactive and pain/anti-inflammatory medications conducted in the full sample of 2,301 men were conducted using weighted analyses. To be representative of the city of Boston (MA, USA), observations were weighted inversely proportional to their probability of selection.[21]

Results

Characteristics of the analysis sample, overall and by AHT indication, are presented in Table 1. The age range was 30-79 years with a mean age of 47.6 years. A total of 617 men (20.7%) were classified as having ED (IIEF-5 <17). Among men with AHT indication, there were 337 men with IIEF-5 <17 (prevalence of 37.5%). Overall, one third of men in the BACH Survey were obese and 40% were overweight. Prevalence of heart disease, diabetes, and arthritis were 10.1%, 9.3%, 17.3% respectively, while prevalence of depression was 14%. Of 2,301 men in the BACH study, 863 (37.5%) met the criteria for AHT indication. Men with AHT indication were significantly older (mean age 57.0) compared to those without the indication (43.3). While distribution by race/ethnicity was comparable, the AHT indication group had higher prevalence of obesity (40.8%), heart disease (32.1%), diabetes (23.2%) and arthritis (30.1%), while prevalence of depression was comparable (15.7%).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of analysis sample, overall and by antihypertensive indication. N(weighted%).

| Overall N=2,301 | AHT indication N=863 | No AHT indication N=1,438 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean (SE) | 47.6 (0.45) | 57.0 (0.80) | 43.3 (0.41) |

| 30-39 | 615 (37.2) | 68 (10.9) | 547 (49.4) | |

| 40-49 | 659 (25.8) | 182 (21.1) | 477 (28.0) | |

| 50-59 | 510 (17.8) | 246 (26.3) | 264 (13.9) | |

| 60-79 | 517 (19.2) | 367 (41.7) | 150 (8.7) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | White | 835 (61.9) | 303 (57.4) | 532 (64.1) |

| Black | 700 (25.0) | 318 (31.5) | 382 (22.0) | |

| Hispanic | 766 (13.0) | 242 (11.1) | 524 (13.9) | |

| Socioeconomic Status | Low | 970 (24.3) | 422 (36.2) | 548 (18.8) |

| Middle | 954 (49.1) | 333 (42.8) | 621 (52.0) | |

| High | 377 (26.6) | 108 (21.0) | 269 (29.2) | |

| BMI | <25 | 596 (26.6) | 153 (16.1) | 443 (31.5) |

| 25-29 | 905 (40.7) | 318 (43.1) | 586 (39.6) | |

| 30+ | 801 (32.7) | 392 (40.8) | 409 (28.9) | |

| Physical Activity (PASE) | Low | 694 (26.8) | 382 (40.1) | 313 (20.7) |

| Moderate | 1069 (47.4) | 346 (42.9) | 723 (49.4) | |

| High | 538 (25.8) | 135 (17.0) | 402 (29.9) | |

| Smoking | Never | 878 (38.9) | 269 (30.4) | 609 (42.8) |

| Former | 665 (28.9) | 308 (38.2) | 357 (24.6) | |

| Current | 757 (32.2) | 285 (31.4) | 472 (32.6) | |

| Alcohol consumption | Never | 800 (27.5) | 384 (40.5) | 416 (21.4) |

| <1/day | 815 (38.9) | 273 (34.3) | 542 (41.0) | |

| 1-2.9/day | 434 (24.1) | 124 (16.7) | 310 (27.5) | |

| 3+/day | 252 (9.58) | 82 (8.5) | 170 (10.1) | |

| Heart disease | Y | 248 (10.1) | 248 (32.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| N | 2053 (89.9) | 615 (67.9) | 1438 (100.0) | |

| Depression | Y | 391 (14.0) | 181 (15.7) | 210 (13.2) |

| N | 1910 (86.0) | 682 (84.3) | 1228 (86.8) | |

| Diabetes | Y | 298 (9.3) | 237 (23.2) | 61 (2.9) |

| N | 2003 (90.7) | 626 (76.8) | 1377 (97.1) | |

| Arthritis | Y | 444 (17.3) | 266 (30.1) | 177 (11.3) |

| N | 1857 (82.7) | 597 (69.9) | 1261 (88.7) |

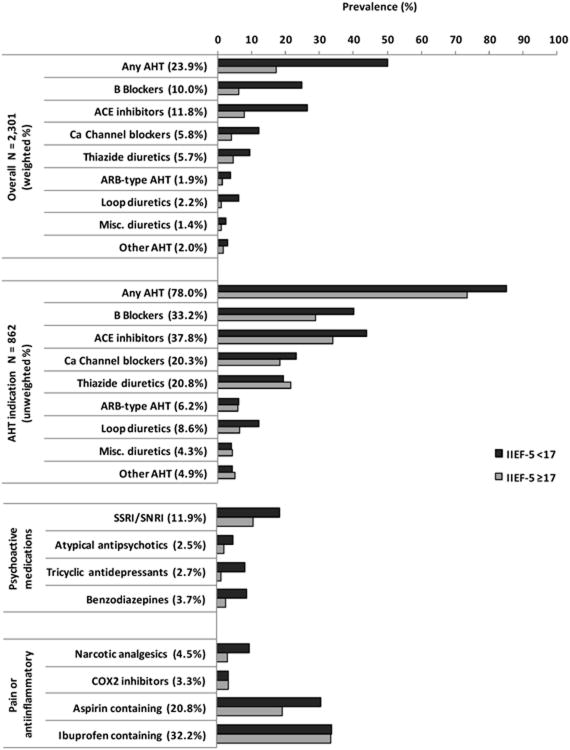

Prevalence of prescription medication use, overall and by ED status, is presented in Figure 1. Overall prevalence of use of any AHT was 23.9% (N=672) with ACE inhibitors and beta blockers the most commonly used AHTs at 11.8% (N=326) and 10.0% (N=286), respectively, followed by CCBs and thiazide diuretics at 5.8% (N=175) and 5.7% (N=179), respectively. Prevalence of ARB-type AHTs and loop diuretics was 1.9% (N=53) and 2.2% (N=74), respectively. AHT use was much higher among men with ED. However, when analyses were restricted to men with AHT indication, the difference in AHT use between men with and without ED was reduced substantially.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of prescription medication use, overall and by ED status. Prevalence of antihypertensive (AHT) medications use presented overall (N=2,301, weighted %) and among those with an indication for antihypertensive medication use (N=862, unweighted %).

Of antidepressant medications included in the analysis, SSRI/SNRIs were most commonly used (11.9%) while use of tricyclic antidepressants, atypical antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines ranged between 2.5%-3.7%. Use of antidepressant medications was consistently higher among men with ED. In contrast, use of pain/anti-inflammatory medications was elevated among men with ED compared to men without for narcotic analgesics and aspirin-containing medications but did not differ for COX2 inhibitors and ibuprofen-containing medications.

Association of potential confounders included in the analysis with ED is presented in Table 2. Increased odds of ED were observed with older age and presence of comorbid conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, and depression. Decreased odds of ED were observed with increased physical activity levels and moderate alcohol consumption. These associations were also observed among men with AHT indication.

Table 2.

Association of potential confounders included in the analysis and ED. Age-adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

| All, N=2,301 Weighted ORs (95%CI) | AHT indication, N=862 Unweighted ORs (95%CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 30-39 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 40-49 | 1.57 (0.99, 2.48) | 0.91 (0.45, 1.82) | |

| 50-59 | 2.97 (1.86, 4.76) | 1.60 (0.83, 3.08) | |

| 60-79 | 7.34 (4.81, 11.2) | 3.95 (2.12, 7.36) | |

| Race/ethnicity | white | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| black | 1.78 (1.21, 2.61) | 1.47 (1.01, 2.13) | |

| Hispanic | 2.34 (1.55, 3.52) | 1.72 (1.16, 2.57) | |

| SES | Low | 3.24 (2.14, 4.89) | 2.53 (1.77, 3.60) |

| Middle | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| High | 0.79 (0.50, 1.25) | 0.88 (0.52, 1.49) | |

| BMI | <25 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 25-29 | 1.15 (0.75, 1.77) | 0.93 (0.58, 1.49) | |

| 30+ | 1.18 (0.76, 1.83) | 1.15 (0.73, 1.81) | |

| Physical activity (PASE) | Low (<100) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium (100-250) | 0.51 (0.36, 0.74) | 0.55 (0.40, 0.76) | |

| High (>250) | 0.31 (0.19, 0.50) | 0.29 (0.17, 0.50) | |

| Alcohol consumption | None | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| <1/day | 0.54 (0.36, 0.79) | 0.75 (0.52, 1.07) | |

| 1-3/day | 0.50 (0.30, 0.82) | 0.58 (0.35, 0.93) | |

| 3+/day | 0.62 (0.36, 1.06) | 0.73 (0.42, 1.28) | |

| Smoking | Never | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Former | 1.07 (0.68, 1.68) | 0.90 (0.61, 1.32) | |

| Current | 1.49 (1.01, 2.20) | 1.53 (1.05, 2.24) | |

| Heart Disease | 2.82 (1.81, 4.38) | 1.78 (1.24, 2.55) | |

| Diabetes | 2.90 (1.78, 4.73) | 1.72 (1.23, 2.41) | |

| Arthritis | 1.38 (1.00, 1.92) | 1.36 (0.99, 1.87) | |

| Depression | 2.94 (1.92, 4.49) | 2.72 (1.86, 3.98) |

Unadjusted ORs.

To avoid confounding by indication, analyses of the association of AHT medications and ED were conducted in a subgroup of 862 men who meet the criteria for AHT treatment (Table 3). Unadjusted analyses show an association of any AHT medications with ED (unadjusted OR=2.08, 95%CI:1.44, 1.91), and more specifically, for beta blockers (unadjusted OR=1.65, 95%CI:1.21, 2.25) and ACE inhibitors (unadjusted OR=2.27, 95%CI:1.37, 3.78). As there is substantial overlap in the use of different AHT classes, the effect of specific AHT classes was assessed using a four level variable (No AHT use, other AHT, Specific AHT (e.g. beta blocker) with other AHT, and specific AHT only). Results confirm the crude association of beta blockers only and ACE inhibitors only with unadjusted ORs of 2.59 (95%CI:1.47, 4.57)and 2.27 (95%CI: 1.37, 3.78) respectively; significant associations were also observed when these drugs were used with other AHTs. However, these associations were attenuated and statistically non-significant after adjusting for age. The magnitude of these associations was further attenuated towards the null in multivariable models adjusting for potential confounders including age, race/ethnicity, SES, BMI, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, and depression. No associations were consistently observed for other AHT classes (e.g. thiazide diuretics or CCBs) and ED across a variety of modeling strategies.

Table 3.

Association of antihypertensive (AHT) medications and ED (IIEF-5 <17) among those with an indication for AHT medication use (N = 862). Unweighted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

| ED | OR(95%CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Yes | No | Unadjusted | Age-Adjusted | Full model* | Reduced model** | ||

| Any AHT | Yes | 286 | 386 | 2.08 (1.44, 3.02) | 1.27 (0.85, 1.91) | 1.09 (0.71, 1.69) | 1.13 (0.73, 1.74) |

| No | 50 | 140 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Number of AHTs | 0 | 50 | 140 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 143 | 209 | 1.92 (1.28, 2.89) | 1.27 (0.83, 1.97) | 1.17 (0.73, 1.88) | 1.20 (0.75, 1.92) | |

| 2 | 79 | 104 | 2.12 (1.35, 3.34) | 1.23 (0.76, 2.01) | 1.07 (0.63, 1.81) | 1.12 (0.66, 1.90) | |

| 3+ | 64 | 73 | 2.48 (1.54, 4.01) | 1.33 (0.79, 2.24) | 0.89 (0.49, 1.60) | 0.96 (0.54, 1.70) | |

| p-trend <0.001 | p-trend = 0.380 | p-trend = 0.563 | p-trend = 0.752 | ||||

| Beta Blockers | Yes | 134 | 152 | 1.65 (1.21, 2.25) | 1.27 (0.91, 1.76) | 1.02 (0.7, 1.48) | 1.03 (0.72, 1.5) |

| No | 201 | 375 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Beta Blockers only | 43 | 46 | 2.59 (1.47, 4.57) | 1.73 (0.94, 3.18) | 1.33 (0.69, 2.57) | 1.40 (0.73, 2.67) | |

| Beta Blockers + other AHTs | 92 | 105 | 2.45 (1.58, 3.81) | 1.31 (0.81, 2.11) | 0.98 (0.58, 1.67) | 1.01 (0.60, 1.72) | |

| other AHTs, no Beta Blockers | 151 | 235 | 1.82 (1.21, 2.72) | 1.17 (0.76, 1.81) | 1.09 (0.68, 1.74) | 1.12 (0.71, 1.79) | |

| No AHT use (referent) | 50 | 140 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| ACE inhibitors | Yes | 148 | 178 | 1.53 (1.14, 2.06) | 1.30 (0.95, 1.78) | 1.16 (0.81, 1.66) | 1.12 (0.79, 1.59) |

| No | 188 | 348 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| ACE inhibitors only | 55 | 68 | 2.27 (1.37, 3.78) | 1.63 (0.96, 2.77) | 1.58 (0.87, 2.85) | 1.52 (0.85, 2.73) | |

| ACE inhibitors + other AHTs | 93 | 110 | 2.36 (1.53, 3.66) | 1.30 (0.81, 2.11) | 0.98 (0.57, 1.67) | 1.02 (0.60, 1.73) | |

| other AHTs, no ACE inhibitors | 138 | 208 | 1.87 (1.25, 2.81) | 1.13 (0.73, 1.76) | 1.01 (0.63, 1.62) | 1.08 (0.68, 1.72) | |

| No AHT use (referent) | 50 | 140 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Ca channel | Yes | 78 | 97 | 1.35 (0.95, 1.92) | 1.09 (0.75, 1.58) | 0.99 (0.65, 1.49) | 1.05 (0.70, 1.57) |

| Blockers (CCBs) | No | 257 | 429 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Ca channel blockers only | 15 | 30 | 1.40 (0.69, 2.86) | 0.91 (0.43, 1.93) | 0.93 (0.42, 2.05) | 0.96 (0.44, 2.12) | |

| Ca channel blockers + other AHTs | 63 | 67 | 2.67 (1.63, 4.36) | 1.48 (0.87, 2.53) | 1.12 (0.62, 2.03) | 1.23 (0.69, 2.2) | |

| other AHTs, no Ca Channel Blockers | 208 | 289 | 2.02 (1.37, 2.97) | 1.27 (0.84, 1.92) | 1.11 (0.71, 1.73) | 1.13 (0.72, 1.76) | |

| No AHT use (referent) | 50 | 140 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Thiazide | Yes | 65 | 114 | 0.86 (0.59, 1.25) | 0.80 (0.54, 1.19) | 0.81 (0.53, 1.25) | 0.85 (0.56, 1.30) |

| diuretics | No | 271 | 412 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Thiazide diuretics only | 11 | 26 | 1.15 (0.49, 2.73) | 0.86 (0.36, 2.04) | 0.86 (0.35, 2.14) | 0.89 (0.36, 2.21) | |

| Thiazide diuretics + other AHTs | 54 | 88 | 1.72 (1.04, 2.82) | 1.07 (0.63, 1.84) | 0.93 (0.52, 1.66) | 1.00 (0.56, 1.77) | |

| other AHTs, no Thiazide diuretics | 221 | 272 | 2.29 (1.56, 3.35) | 1.38 (0.91, 2.09) | 1.17 (0.74, 1.82) | 1.2 (0.77, 1.87) | |

| No AHT use (referent) | 50 | 140 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| ARB-type antiHT | Yes | 21 | 32 | 1.02 (0.55, 1.89) | 0.84 (0.45, 1.56) | 0.83 (0.42, 1.66) | 0.83 (0.42, 1.63) |

| No | 315 | 494 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| ARB only | 2 | 5 | 1.01 (0.16, 6.34) | 0.64 (0.09, 4.55) | 0.68 (0.09, 5.27) | 0.61 (0.08, 4.69) | |

| ARB diuretics + other AHTs | 19 | 27 | 1.99 (0.97, 4.08) | 1.11 (0.54, 2.30) | 0.94 (0.41, 2.13) | 0.98 (0.44, 2.19) | |

| other AHTs, no ARB diuretics | 265 | 354 | 2.10 (1.45, 3.06) | 1.29 (0.86, 1.94) | 1.11 (0.72, 1.72) | 1.15 (0.74, 1.78) | |

| No AHT use (referent) | 50 | 140 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Loop diuretics | Yes | 40 | 34 | 2.01 (1.21, 3.34) | 1.44 (0.86, 2.41) | 0.82 (0.46, 1.46) | 0.87 (0.50, 1.52) |

| No | 295 | 493 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Loop diuretics only | 2 | 3 | 1.80 (0.27, 11.87) | 0.83 (0.17, 4.08) | 0.38 (0.08, 1.73) | 0.52 (0.11, 2.54) | |

| Loop diuretics + other AHTs | 38 | 31 | 3.55 (1.95, 6.47) | 1.81 (0.96, 3.39) | 0.96 (0.47, 1.94) | 1.03 (0.52, 2.02) | |

| other AHTs, no Loop diuretics | 245 | 353 | 1.96 (1.34, 2.85) | 1.24 (0.82, 1.86) | 1.11 (0.72, 1.72) | 1.15 (0.74, 1.78) | |

| No AHT use | 50 | 140 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| misc. diuretics | Yes | 14 | 23 | 0.97 (0.48, 1.95) | 0.77 (0.38, 1.59) | 0.83 (0.4, 1.75) | 0.85 (0.41, 1.77) |

| No | 321 | 203 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| misc diuretics only | 1 | 3 | 1.39 (0.12, 16.2) | 1.06 (0.09, 12.90) | 0.94 (0.07, 12.48) | 1.07 (0.09, 13.53) | |

| misc diuretics + other AHTs | 13 | 20 | 1.77 (0.80, 3.92) | 0.94 (0.41, 2.15) | 0.9 (0.38, 2.11) | 0.93 (0.40, 2.16) | |

| otherAHTs, no misc. diuretics | 272 | 363 | 2.10 (1.45, 3.06) | 1.29 (0.86, 1.94) | 1.1 (0.71, 1.71) | 1.14 (0.74, 1.77) | |

| No AHT use (referent) | 50 | 140 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Other AHT | Yes | 14 | 28 | 0.80 (0.41, 1.56) | 0.58 (0.29, 1.17) | 0.75 (0.35, 1.62) | 0.77 (0.37, 1.59) |

| not otherwise classified (noc) | No | 321 | 498 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| other AHTs | 271 | 359 | 2.13 (1.47, 3.10) | 1.31 (0.87, 1.97) | 1.12 (0.72, 1.73) | 1.15 (0.75, 1.78) | |

| Other AHT (noc) only | 14 | 28 | 1.45 (0.70, 3.02) | 0.73 (0.34, 1.59) | 0.82 (0.35, 1.92) | 0.86 (0.38, 1.95) | |

| No AHT use (referent) | 50 | 140 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

age, race/ethnicity, SES, BMI, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, depression

age, SES, physical activity, heart disease, diabetes, depression

The association of psychoactive medications and pain/anti-inflammatory medications with ED is presented in Table 4. Use of SSRI/SNRI and atypical antipsychotics was associated with an approximately two-fold increase in odds of ED in unadjusted analyses. As with AHTs, this association was attenuated in multivariable analyses and was no longer statistically significant. However, associations of larger magnitude were initially observed for tricyclic antidepressants and benzodiazepines and were robust in multivariable analyses adjusting for potential confounders. Adjusted ORs from the full model were 3.35 (95%CI:1.09,10.27) for tricyclic antidepressants and 2.34 (95%CI:1.03, 5.31) for benzodiazepines. Of pain/anti-inflammatory medications included in the analyses, association of narcotic analgesics and aspirin containing medications were associated with three- and two-fold increased in odds of ED in unadjusted analyses. These associations were attenuated and statistically non-significant in multivariable analyses with ORs of 1.71 (95%CI:0.86, 3.39) for narcotic analgesics and 1.15 (95%CI:0.72,1.85) for aspirin containing medications.

Table 4.

Association of psychoactive and pain/antiinflammatory medications with ED (IIEF-5 <17) among BACH men (N =2,301). Weighted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

| OR (95%CI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| IIEF<17 | IIEF 17+ | Unadjusted | Age-Adjusted | Full model | Reduced model | ||

| SSRI/SNRI | Y | 80 | 147 | 1.86 (1.11, 3.11) | 1.81 (1.11, 2.95) | 1.20 (0.70, 2.07) | 1.17 (0.69, 2.00) |

| N | 535 | 1539 | |||||

| Atypical antipsychotics | Y | 29 | 38 | 2.32 (1.07, 5.02) | 2.91 (1.29, 6.59) | 1.44 (0.56, 3.72) | 1.49 (0.56, 3.94) |

| N | 585 | 1649 | |||||

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Y | 28 | 32 | 6.44 (3.06, 13.57) | 5.67 (2.12, 15.17) | 3.35 (1.09, 10.27) | 3.39 (1.22, 9.45) |

| N | 586 | 1655 | |||||

| Benzodiazepines | Y | 46 | 47 | 3.65 (1.84, 7.22) | 3.64 (1.67, 7.94) | 2.34 (1.03, 5.31) | 2.33 (1.06, 5.12) |

| N | 568 | 1640 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Narcotic analgesics | Y | 63 | 58 | 3.10 (1.52, 6.29) | 2.83 (1.37, 5.86) | 1.71 (0.86, 3.39) | 1.7 (0.83, 3.45) |

| N | 555 | 1628 | |||||

| COX2 inhibitors | Y | 21 | 40 | 0.98 (0.36, 2.64) | 0.85 (0.34, 2.18) | 0.64 (0.24, 1.72) | 0.63 (0.23, 1.71) |

| N | 594 | 1646 | |||||

| Aspirin containing | Y | 160 | 301 | 1.83 (1.27, 2.64) | 1.26 (0.82, 1.93) | 1.15 (0.72, 1.85) | 1.10(0.70, 1.75) |

| N | 454 | 1386 | |||||

| Ibuprofen containing | Y | 156 | 489 | 1.01 (0.68, 1.50) | 1.24 (0.82, 1.86) | 1.45 (0.92, 2.28) | 1.46 (0.94, 2.27) |

| N | 458 | 1198 | |||||

age, race/ethnicity, SES, BMI, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, depression

age, SES, physical activity, heart disease, diabetes, depression

Discussion

Results of the BACH Survey show that of commonly used prescription medications (antihypertensive, psychoactive, and pain and anti-inflammatory), psychoactive medications are most likely to be associated with ED. Specifically, benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants were associated with two- to three-fold increase in odds of ED, while no association of SSRI/SNRIs and atypical antipsychotics with ED was observed after accounting for sociodemographic, lifestyle, and comorbid conditions.

Sexual dysfunction as a possible consequence of antidepressant therapy has been recognized. In addition to earlier antidepressant agents such as tricyclic antidepressant and monoamine oxidase inhibitors, more recent commonly used agents such as SSRIs and SNRIs have also been associated with sexual dysfunction.[22, 23] SSRIs may affect erectile function through a variety of pathways, including nitric oxide synthesis, an effect of serotonin on dopamine levels in the brain, and on vascular and genital smooth muscle.[24] However, as depression itself has been shown to be associated with ED independent of age and comorbid conditions, separating drug-induced effects from consequences of the illness itself is difficult. The temporality of the associations in this analysis cannot be known, i.e., ED may cause depression or anxiety and be reflected in the use of tricyclics or benzodiazepines. In the HPFS, use of antidepressant medication (type not given--relative risk=1.7, 95%CI:1.2, 2.2) was associated with ED after adjusting for sociodemographic and lifestyle factors as well as comorbid conditions but authors did not adjust for depression.[6] The association of antidepressants (including SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressant, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, thioridazine, fluphenazine, and clonazepam) with ED was of larger magnitude in analyses of NHANES data with an OR of 5.19 (95%CI:1.7, 15.9) adjusted for age and comorbid conditions but again, not for depression.[7] Results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study (MMAS) on SSRIs, other antidepressants, and benzodiazepines found a significant association of benzodiazepines and ED (adjusted OR=1.98, 95%CI:1.11, 3.53).[9] Results from our analyses of BACH data show that the association of SSRIs/SNRIs and atypical antipsychotics with ED is attenuated and statistically non-significant after adjusting for potential confounders while both tricyclic antidepressants and benzodiazepines were associated with significantly increased odds of ED. The benzodiazepine and ED association is consistent with results of the MMAS with a similar two-fold increase in odds of ED.

While endothelial function is thought to be the common link between ED and cardiovascular disease,[25] the association between ED and hypertension may involve other aspects, such as the hemodynamic interferences caused by antihypertensive drugs.[26] Although increased prevalence of ED among men with treated hypertension compared to no treatment has been reported,[27] it is likely that the impact on ED varies by antihypertensive drug class.[8] Results from large clinical trials among patients with cardiovascular disease, hypertension, or diabetes show no effect or a positive effect of AHT on ED.[28-30] A recent systematic review of clinical trials of AHT medications including assessment of ED suggests that only thiazide diuretics and beta blockers adversely affect erectile function while ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and CCBs showed no adverse effect or showed a positive effect.[8] Our results show no associations for any AHT with ED, whether in monotherapy or when used with other AHTs, after multivariable adjustment for confounders.

While previous population-based studies have reported associations of some AHT medication classes and ED, primarily diuretics and beta blockers, as with clinical studies results have not been consistent. Data from NHANES 2001-2002 show a two-fold increased in odds of ED with AHT use among hypertensive men after adjusting for potential confounders.[7] However the effect of different AHT drug classes was not investigated. Results of the HPFS show a modest increase in risk of ED with beta blockers (adjusted OR=1.2, 95%CI:1.1, 1.5) and alpha blockers (adjusted OR=1.3, 95%CI:1.0, 1.7),[6] while data from MMAS show only thiazide diuretics to be associated with ED (adjusted OR=2.81, 95%CI:1.11, 7.14).[9] Finally, results from a longitudinal study of 1000 men age 55 to 75 and without ED at baseline show increased risk of incident ED with use of angiotensin II antagonists (adjusted OR=2.2, 95%CI:1.0, 4.7) and CCBs (adjusted OR=1.6, 95%CI:1.0, 2.4) over a 5-year follow-up period.[31]

Inconsistent results from comparable population-based studies may be explained by not having restricted analyses to AHT indication groups resulting in residual confounding. Furthermore, to our knowledge, the overlap of AHT medications use (combination vs. monotherapy) has not previously been addressed. Results of our analyses, conducted among men with an indication for AHT treatment, suggest that the association between AHT medications and ED is confounded by age and comorbid conditions such as diabetes and heart disease. While odds of ED were increased in unadjusted analyses with beta blocker or ACE inhibitor use, especially with use of these medications only, associations were attenuated and statistically non-significant in multivariable analyses adjusting for age and other confounders.

Few studies have investigated the association of anti-inflammatory and pain medications with ED. Data from the California Men's Health Study show a modest increase in odds of severe ED with NSAIDS use after accounting for sociodemographic factors and comorbid conditions (adjusted OR=1.38, 95%CI:1.29, 1.47).[10] Results from a prospective Finnish study show an increased risk of incident ED with NSAIDS use in men with arthritis (adjusted OR=2.0, 95%CI:1.2, 3.5) or without arthritis (adjusted OR=1.9, 95%CI:1.2, 3.1) compared to men who did not use NSAIDS and were free of arthritis. Risk of ED was not significantly elevated for men with arthritis who did not use NSAIDS (adjusted OR=1.3, 95%CI:0.9, 1.8).[11] Results of the present analyses show no association of anti-inflammatory medications in multivariable models. We did not know whether the anti-inflammatory medications captured in our study were used daily or episodically; as such our exposures may be less consistent than with AHTs used daily.

This study has many strengths; however there are some important limitations. Strengths include a community-based random sample encompassing a broad age range (30-79 yrs), representation of both the black and Hispanic populations and a wide range of covariates. Additionally the ability to conduct analyses among men with AHT indication limits the possibility of confounding by indication in the assessment of the association of AHT medications and ED. ED was assessed using the IIEF-5, a validated instrument of for ED assessment widely used in both clinical and epidemiologic studies. A limitation of the IIEF-5 is recall bias among men who had not engaged in sexual activity in the 4 weeks preceding completion of the questionnaire, potentially resulting in greater misclassification in this group. Another strength is assessment of medication use though a combination of inventory and self-report with indication. A limitation is the small number of men reporting use of certain medication resulting in imprecise confidence intervals and limiting the possibility of subgroup analyses. The BACH Survey was limited geographically to the Boston Area. However, comparison of sociodemographic and health-related variables from BACH with other large regional surveys (Boston BRFSS) and national surveys (NHANES) has shown that BACH estimates are comparable to national trends on key health-related variables.[13] Finally, our cross-sectional analysis allows us to capture associations but do not allow us to conclude that observed associations are causal in nature or determine the temporality of the association (i.e., whether exposure or outcome came first).

In summary, results of the BACH Survey suggest positive associations of tricyclic antidepressant and benzodiazepines with ED. In contrast, AHT medications were not associated with decreased erectile function after accounting for age and comorbid conditions. Similarly, no multivariable adjusted associations were observed between pain medications including anti-inflammatories and ED.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Award Number R21DK082652 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (NIH). Funding for the BACH Survey was provided by NIDDK DK 56842. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDDK or the NIH.

References

- 1.Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994 Jan;151:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saigal CS, Wessells H, Pace J, Schonlau M, Wilt TJ. Predictors and prevalence of erectile dysfunction in a racially diverse population. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jan 23;166:207–12. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laumann EO, West S, Glasser D, Carson C, Rosen R, Kang JH. Prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction by race and ethnicity among men aged 40 or older in the United States: from the male attitudes regarding sexual health survey. J Sex Med. 2007 Jan;4:57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman HA, Johannes CB, Derby CA, et al. Erectile dysfunction and coronary risk factors: prospective results from the Massachusetts male aging study. Prev Med. 2000 Apr;30:328–38. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Londono DC, Slezak JM, Quinn VP, Van Den Eeden SK, Loo RK, Jacobsen SJ. Population-based study of erectile dysfunction and polypharmacy. BJU Int. 2012 Jul;110:254–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacon CG, Mittleman MA, Kawachi I, Giovannucci E, Glasser DB, Rimm EB. Sexual function in men older than 50 years of age: results from the health professionals follow-up study. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Aug 5;139:161–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-3-200308050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francis ME, Kusek JW, Nyberg LM, Eggers PW. The contribution of common medical conditions and drug exposures to erectile dysfunction in adult males. J Urol. 2007;178:591–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.127. discussion 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumhakel M, Schlimmer N, Kratz M, Hackett G, Jackson G, Bohm M. Cardiovascular risk, drugs and erectile function--a systematic analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2011 Mar;65:289–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derby CA, Barbour MM, Hume AL, McKinlay JB. Drug therapy and prevalence of erectile dysfunction in the Massachusetts Male Aging Study cohort. Pharmacotherapy. 2001 Jun;21:676–83. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.7.676.34571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gleason JM, Slezak JM, Jung H, et al. Regular nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2011 Apr;185:1388–93. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiri R, Koskimaki J, Hakkinen J, Tammela TL, Auvinen A, Hakama M. Effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use on the incidence of erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2006;175:1812, 5. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)01000-1. discussion 5-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall SA, Kupelian V, Rosen RC, et al. Is hyperlipidemia or its treatment associated with erectile dysfunction?: Results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. J Sex Med. 2009 May;6:1402–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the urologic iceberg: design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007 Aug;52:389–96. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, Lipsky J, Pena BM. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999 Dec;11:319–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelley KE, Kelley TP, Kaufman DW, Mitchell AA. The Slone Drug Dictionary: A research driven pharmacoepidemiology tool. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety. 2003;12:168–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993 Feb;46:153–62. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green LW. Manual for scoring socioeconomic status for research on health behavior. Public Health Rep. 1970 Sep;85:815–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999 Jun;11:139–48. doi: 10.1017/s1041610299005694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grobbee DE, Hoes AW. Confounding and indication for treatment in evaluation of drug treatment for hypertension. BMJ. 1997 Nov 1;315:1151–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7116.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schafer J. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. London: Chapman and Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cochran W. Sampling Techniques. 3rd. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen RC, Marin H. Prevalence of antidepressant-associated erectile dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(10):5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montgomery SA, Baldwin DS, Riley A. Antidepressant medications: a review of the evidence for drug-induced sexual dysfunction. J Affect Disord. 2002 May;69:119–40. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Labbate LA, Croft HA, Oleshansky MA. Antidepressant-related erectile dysfunction: management via avoidance, switching antidepressants, antidotes, and adaptation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(10):11–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ganz P. Erectile dysfunction: pathophysiologic mechanisms pointing to underlying cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005 Dec 26;96:8M–12M. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Javaroni V, Neves MF. Erectile dysfunction and hypertension: impact on cardiovascular risk and treatment. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012:627278. doi: 10.1155/2012/627278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doumas M, Tsakiris A, Douma S, et al. Factors affecting the increased prevalence of erectile dysfunction in Greek hypertensive compared with normotensive subjects. J Androl. 2006 May-Jun;27:469–77. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.04191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth A, Kalter-Leibovici O, Kerbis Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in men with diabetes, hypertension, or both diseases: a community survey among 1,412 Israeli men. Clin Cardiol. 2003 Jan;26:25–30. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960260106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baumhakel M, Schlimmer N, Bohm M. Effect of irbesartan on erectile function in patients with hypertension and metabolic syndrome. Int J Impot Res. 2008 Sep-Oct;20:493–500. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2008.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bohm M, Baumhakel M, Probstfield JL, et al. Sexual function, satisfaction, and association of erectile dysfunction with cardiovascular disease and risk factors in cardiovascular high-risk patients: substudy of the ONgoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial/Telmisartan Randomized AssessmeNT Study in ACE-INtolerant Subjects with Cardiovascular Disease (ONTARGET/TRANSCEND) Am Heart J. 2007 Jul;154:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shiri R, Koskimaki J, Hakkinen J, Auvinen A, Tammela TL, Hakama M. Cardiovascular drug use and the incidence of erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2007 Mar-Apr;19:208–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]