Abstract

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is the primary regulator of mammalian reproductive function in both males and females. It acts via G-protein coupled receptors on gonadotropes to stimulate synthesis and secretion of the gonadotropin hormones luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone. These receptors couple primarily via G-proteins of the Gq/ll family, driving activation of phospholipases C and mediating GnRH effects on gonadotropin synthesis and secretion. There is also good evidence that GnRH causes activation of other heterotrimeric G-proteins (Gs and Gi) with consequent effects on cyclic AMP production, as well as for effects on the soluble and particulate guanylyl cyclases that generate cGMP. Here we provide an overview of these pathways. We emphasize mechanisms underpinning pulsatile hormone signaling and the possible interplay of GnRH and autocrine or paracrine regulatory mechanisms in control of cyclic nucleotide signaling.

Keywords: GnRH, G-proteins, phospholipase C, adenylyl cyclase, guanylyl cyclase, ERK, PACAP, natriuretic peptide

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptors and Effectors

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) (pGlu-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr-Gly-Leu-Arg-Pro-Gly-NH2), also known as luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) or GnRH I, is a hypothalamic neuropeptide that mediates central control of reproduction in both males and females. It is synthesized in hypothalamic neurons and secreted from the hypothalamus into the hypophyseal portal circulation in pulses which are most often of a few minutes duration. It acts via GnRH receptors (GnRHRs) on gonadotropes within the anterior pituitary, stimulating the synthesis and secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), thereby controlling gametogenesis and steroidogenesis (1–6). GnRH is absolutely required for reproduction as demonstrated by mutation of the genes encoding GnRH or its receptor (7–9).

Molecular phylogeny of GnRH ligands shows that there are three distinct forms, GnRH-I, GnRH-II, and GnRH-III that arose from a common origin which predates vertebrates (10). Most vertebrate classes have GnRH-I and GnRH-II (1, 3, 11), whereas GnRH-III has only been found in teleosts (12–23). Interestingly, the GnRH-I sequence has diverged in the vertebrate lineage, whereas the sequences of GnRH-II and GnRH-III are completely conserved across vertebrates (3, 10, 24).

Clinical Uses

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs are used clinically, either to mimic its stimulatory effects, such as the treatment of infertility with pulsatile administration of a natural sequence of GnRH to induce ovulation or spermatogenesis (3, 25), or to block its effects. The latter can be achieved either using GnRH antagonists (1–6, 26, 27), or, paradoxically, with sustained exposure to GnRH (or metabolically stable GnRH agonists), which causes stimulation followed by desensitization of GnRHR-mediated gonadotropin secretion (3, 25). In both cases blockade or desensitization of GnRHR-mediated gonadotropin secretion ultimately reduce circulating levels of gonadotropins and gonadal steroids, and in this fashion GnRH analogs can be used to treat sex hormone-dependent neoplasms such as those of the prostate, ovary, endometrium, or mammary glands (1–6, 28).

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone

GnRH receptors belong to the rhodopsin-like G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) family, and are thus characterized by a seven trans-membrane α helical domain structure (3, 29, 30). GnRHRs can be classified into three groups based on sequence homology. All of the cloned mammalian GnRHRs are in groups I or II (3, 24) and the type I GnRHRs of humans, rats, mice, pigs, sheep, and horses have >80% amino acid sequence homology (31). Except in certain primate species, notably the marmoset, rhesus, and green monkey, the type I receptor is the functional and predominant form expressed in the mammalian gonadotrope, and in some species it is also expressed in extra-pituitary tissues including breast, gonads, prostate, and uterus (32, 33). This extra-pituitary expression is also evident in numerous cancers, including breast, prostate and ovary, and on in vitro or in vivo tumor models GnRH analogs or cytotoxic derivatives show promise as anti-proliferative and/or pro-apoptotic agents (34–40).

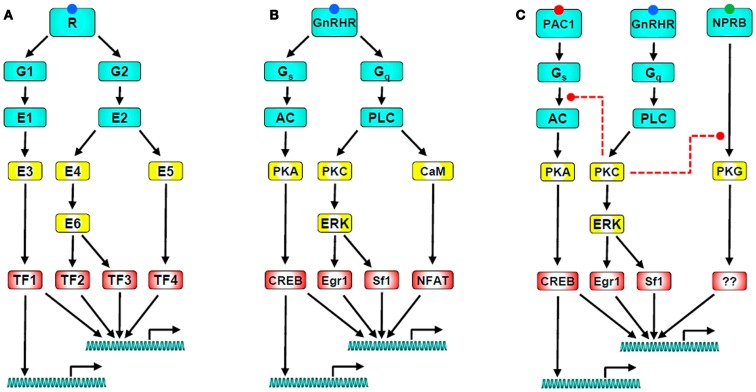

In common with many other GPCRs, GnRHRs of gonadotropes and gonadotrope-lineage cells act primarily via Gαq/11 to activate phospholipase C (PLC), thus elevating cytoplasmic [Ca2+] and activating protein kinase C (PKC) isozymes, both of which are important for GnRHR-mediated effects on gonadotropin synthesis and secretion (Figure 1) (2–6, 29, 31, 41–46). The mammalian type I GnRHR is a structurally and functionally unique member of the GPCR family in that it lacks an intracellular cytoplasmic C-terminal tail (3, 47, 48). For many GPCRs, the C-tail plays a key role in desensitization and trafficking (49, 50). The C-terminal tail of typical GPCRs is phosphorylated on Ser and Thr residues following activation, generating a docking site for non-visual arrestins (arrestins 2 and 3) that prevent G-protein activation, a process termed homologous receptor desensitization. The phosphorylated tails also act as adapters targeting the desensitized receptors for internalization, a process that can lead to receptor down-regulation, or recycling and resensitization (49, 51). The absence of a C-terminal tail would therefore imply an inability of the type I mammalian GnRHR to undergo agonist-induced phosphorylation or bind arrestins, with relatively slow internalization and resistance to rapid desensitization, all of which have been confirmed experimentally (51–61). In addition, fusing the C-terminal of various GPCRs to the type I mammalian GnRHR causes rapid desensitization and internalization (51, 54, 62–65). Both the rat and human GnRHR internalize in a clathrin-dependent manner, and colocalize with transferrin, which is internalized via clathrin-coated structures (54, 56, 59). The rat GnRHR internalizes in a dynamin dependent manner (64), whereas the human internalizes independently of dynamin (47). Contrastingly, upon activation type II GnRHRs do undergo rapid agonist-induced phosphorylation, recruit arrestins, and internalize via clathrin-coated pits (47). The requirement for arrestins and dynamin is species specific (3, 66, 67), but the presence of the C-terminal tail is crucial for rapid agonist-induced internalization (60).

Figure 1.

GnRH receptor signaling networks. (A) Illustrates a generic signaling network in which a GPCR activates two heterotrimeric G-proteins (G1 and G2) which activate their cognate effectors (E1 and E2). These directly or indirectly activate down-stream effectors that influence a range of target proteins including transcription factors (TF1-4). The transcription factors then act (typically in combination) to influence expression of numerous target genes. Note that the network has multiple sites for divergence and convergence. (B) Shows a GnRH signaling network with the same architecture; The GnRHR activates Gs and Gq leading to activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC) and phospholipase C (PLC). AC generates cAMP, stimulating PKA which activates the transcription factor CREB. PLC leads to activation of PKC, driving activation of ERK and of ERK-dependent transcription via Sf-1 and Egr-1. It also elevates the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration, driving activation of calmodulin and its targets, including calcineurin which leads to activation of the Ca2+-dependent transcription factor NFAT. This cartoon is clearly a vast oversimplification as important effectors (including calmodulin-dependent kinases, JNK, p38, and nitric oxide synthase) are not included. Perhaps more importantly, it also excludes signal dynamics and heterologous regulation, both of which are important for control of gonadotropes. A simple example of the latter is given in (C) which includes the PAC1 receptor as a mediator of PACAP-stimulated AC activation, and the NPRB receptor as a mediator of CNP-stimulated cGMP accumulation and consequent protein kinase G (PKG) activation. GnRH can cause PKC-mediated inhibition of PACAP-stimulated cAMP accumulation and of CNP-stimulated cGMP accumulation (as indicated by the dashed red lines), raising the possibility that its predominant effect is actually inhibition of these pathways in gonadotropes exposed to autocrine or paracrine stimulation of PAC1 and NPRB. Finally, when considering signal dynamics, it is important to recognize: (a) that GnRH is secreted in pulses, (b) that the responses illustrated have distinct kinetics, (c) that the kinetics of convergent pathways are important determinants of GnRH pulse frequency-response relationships, and (d) that GnRH influences the expression of many genes encoding components of the GnRHR signaling pathways, with transcription-dependent feedback loops supporting an adaptive signaling network.

Non-mammalian GnRHRs may also activate extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in an arrestin-mediated manner. Arrestins can act as adaptors for signaling molecules, for example cRaf1 and the ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), both of which can bind to MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK), and could therefore participate in MAPK activation (68–72). Arrestin-mediated ERK signaling appears specific for non-mammalian GnRHRs; in cells either expressing a mouse type I or a Xenopus laevis GnRHR, both caused G-protein-dependent ERK activation but arrestin-mediated ERK activation was only seen with the C-tail expressing Xenopus GnRHR (73, 74). An interesting possibility is that the C-terminal tail was lost through evolution because the GnRH pulses that gonadotropes are exposed to would be too short to evoke desensitization of a C-tailed receptor, such that there was no selective advantage for retention of the structure. Alternatively, its loss may be related to the pre-ovulatory gonadotropin surge that is driven by GnRH pulses of increasing frequency and possibly also increased amplitude and a failure to return to basal levels between frequent pulses. Receptor desensitization under such conditions could conceivably prevent the pre-ovulatory gonadotropin surge, providing a positive adaptive advantage for loss of the rapid homologous receptor desensitization mechanism.

Heterotrimeric G-Protein Coupling

In pituitary gonadotropes, GnRHR signaling is primarily mediated by Gαq/11 subunits, although GnRHR coupling to Gαi and Gαs, as well as Gαq/11 have also been reported (75–78). Agonist binding is associated with GTP loading of Gαq/11, which activates phospholipase C β (PLCβ), elaborating the second messengers inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 mediates Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, and DAG causes activation of PKC isozymes (Figure 1). A more sustained rise of intracellular Ca2+ occurs via the opening of L-type voltage gated channels and subsequent Ca2+ influx (1–6, 79). Progressively increasing GnRH concentrations cause three different Ca2+ responses, subthresholds, baseline oscillations, and biphasic responses (80–82). The initial spike phase is due to mobilization of Ca2+ from intracellular stores, which is involved in early GnRH-stimulated LH release (83), whereas the plateau corresponds to Ca2+ entry through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. The oscillatory responses are generated through a cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillator model (84). Rapid effects of GnRH on exocytotic gonadotropin secretion are mediated by elevation of cytoplasmic Ca2+ and modulated by activation of PKC. These signaling intermediates, and effectors including calmodulin and calmodulin-dependent protein kinases (CaMKs), also mediate chronic effects of GnRH on gene expression.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone effects on gonadotropin synthesis are largely mediated through stimulation of MAPK cascades, particularly the ERK pathway (Figure 1) (85), which is PKC dependent in αT3-1 and LβT2 gonadotrope-derived cells (79). PKC and ERK mediate the transcriptional effects of GnRH on the common α-gonadotropin subunit (αGSU) (86–89), as well as LHβ (90–93) and FSHβ (93–96) subunits. However, there are conflicting reports that GnRH-mediated LHβ (88) or αGSU expression (97, 98) are independent of ERK and mediated solely by Ca2+. There are also gender specific difference in mice with pituitary specific knockout of ERK1 and 2; females are infertile due to LH deficiency, and ERKs may play a partial role in FSHβ transcription in these mice, however male reproductive function was normal (99).

In addition to activation of ERK, GnRH can activate the JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase), p38, and ERK5 (also known as Big MAPK; BMK) cascades in different cell models with varying kinetics. GnRH stimulates JNK activity in rat pituitaries, αT3-1 and LβT2 cells (79, 100, 101). JNK has been reported to be involved in transcription of the αGSU subunit (102, 103), and the LHβ and FSHβ subunits (94, 101, 104, 105). JNK-mediated LHβ transcription is independent of PKC in LβT2 (90, 105) and COS (106) cells, with conflicting reports for PKC involvement in αT3-1 cells (85, 107). GnRH also activates p38 in rat pituitaries, αT3-1 and LβT2 cells (91, 94, 103, 104, 108). A role for p38 in gonadotropin subunit transcription is controversial, with no effect being reported on LHβ, FSHβ, and αGSU subunits (91, 103, 104), although an effect on FSHβ transcription in LβT2 cells was reported by others (94, 108). GnRH has also been shown to activate ERK5 and stimulate FSHβ transcription in LβT2 cells (109).

GnRH receptors can also activate a number of other pathways in pituitary gonadotropes, including the adenylyl cyclase (AC)/cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway (79, 110, 111). Borgeat et al. (112) demonstrated that GnRH-stimulated cAMP production in the rat pituitary, which was later confirmed by Naor et al. (113). GnRH also stimulates cAMP production in LβT2 cells (77, 111, 114), and several heterologous systems including HeLa, GH3, and COS-7 cells (115–117). However, this was not replicated in αT3-1 cells or in later studies using rat pituitaries (45, 118, 119). The coupling mechanism between the GnRHR and the cAMP pathway has yet to be elucidated. The GnRHR has been reported to couple to Gαs in rat pituitary cells (76), and activate cAMP production via Gαs recruitment (77). However, in αT3-1 cells the GnRHR exclusively coupled to Gαq/11 (120), and activation of Ca2+/calmodulin sensitive AC isoforms independent of Gαs was proposed as the mechanism of GnRHR-induced cAMP elevation. In addition, the PKC δ and ε isoforms were reported to mediate cAMP elevation by GnRH via activation of AC5 and 7 in LβT2 cells (111). However, a more recent study using a biosensor to monitor cAMP mobilization in living cells has demonstrated that GnRH increases cAMP production in αT3-1 cells, and that the GnRHR directly interacts with SET protein, which inhibits receptor coupling to calcium and increases coupling to the cAMP pathway, possibly by interfering with Gαq/11 binding to the GnRHR (121). In LβT2 and mouse pituitary cells, GnRH activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) via multiple pathways involving Egr-1 and JNK, and AMPK inhibition suppresses GnRH-stimulated LHβ transcription (122).

Gonadotropin promoter subunits contain cAMP response elements (CREs) and this provides a mechanism by which the cAMP/PKA pathway might activate gonadotropin subunit transcription (Figure 1). αT3-1 cells demonstrate a four- to fivefold increase in phospho-CREB (CRE-binding protein) in response to GnRH (123). cAMP stimulates transcription of the mouse, rat, and human αGSU genes (124, 125), and a cAMP analog increased αGSU mRNA levels in rat pituitary cells, but not that of LHβ or FSHβ (126). However, it appears the MAPK cascade, rather than the cAMP pathway, is responsible for gonadotropin promoter CRE activation (90, 100, 107, 127, 128). Here it is important to recognize that CREB can be regulated by MAPKs, CaMKs, and PKC as well as by PKA (129). c-Jun and ATF-2, which are known substrates of JNK, were shown to bind to the CRE domain of the αGSU promoter (130). GnRH phosphorylates ATF-2 via p38 and JNK, and upon phosphorylation ATF-2 binds the CRE element within the c-Jun proximal promoter and interacts with nuclear factor Y. Functional ATF-2 is necessary for both GnRH-mediated induction of c-Jun and FSHβ (131). In addition, GnRH treatment increases expression of ATF-3, which is recruited along with c-Jun and c-Fos to CREs on the αGSU promoter, and GnRH-induced αGSU gene expression was completely abolished upon mutation of these CREs (132). MAPK signaling and ATF-3 CRE binding are essential for secretogranin II promoter activation by GnRH (133).

GnRH receptors activate a large number of important signaling pathways, notably, they mediate activation of phospholipases A2 and D as well as PLC (41). GnRH-mediated intracellular Ca2+ mobilization, acting through calmodulin, also activates kinases such as Ca2+/CaMKs, phosphatases such as calcineurin and transcription factors including nuclear factors of activated T-cells (NFATs) (79, 134). GnRHR-induced elevation of intracellular Ca2+ also activates the nitric oxide synthase (NOS I) cascade (NOS I/NO/soluble guanylate cyclase) resulting in a rapid increase of cGMP (135–137). However there is no evidence that cGMP is involved in GnRH-induced gonadotropin synthesis or secretion (135) (see subsequent section). GnRH also activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway as well as diacylglycerol kinase, proline rich tyrosine kinase-2, and inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase (1, 6, 41, 138–140).

In addition to directly activating a number of intracellular signaling pathways, in some models GnRHRs can also cause a PKC-dependent proteolytic release of membrane bound epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor ligands, thereby activating EGF receptors (1, 41), whereas in others GnRHRs induce protein phosphatases that apparently inhibit the trophic effects of EGF (78). Moreover, in HEK293 cells stably expressing the type I GnRHR, GnRH causes cytoskeletal remodeling, which correlates with significant increases in the tyrosine phosphorylation status of a series of cytoskeletal associated proteins, including focal adhesion kinase (FAK), c-Src, and ERKs (139). ERK activation is dependent on formation of a complex with FAK and c-Src at focal adhesion complexes, and induction of the cell remodeling event is mediated by activation of the monomeric G-protein Rac, revealing a novel monomeric G-protein-mediated pathway for GnRHR signaling (139).

Pulsatile GnRH Signaling

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone is released from hypothalamic neurons as pulses causing pulsatile gonadotropin release (141, 142), and these pulses are essential for normal reproduction; constant GnRH suppresses LH and FSH secretion, and this can be restored by pulsatile administration (143). GnRH pulses are typically a few minutes in duration, every 30–120 min according to the species.

It is well established that the frequency of such pulses is extremely variable. For example, GnRH pulse frequency varies over the menstrual cycle with pulses on average every 6 h in mid- to late-luteal phases and every 90 min during follicular and early luteal phases (144). Low or intermediate pulse frequencies (pulses every 30–120 min) cause a greater increase in expression of rodent LHβ, FSHβ, and the GnRHR as compared to high frequencies (pulses every 8–30 min) or sustained stimulation (145–151). The expression of αGSU does not exhibit this bell-shaped frequency-response relationship and is maximally stimulated by high pulse frequencies or continuous stimulation (148, 149, 152, 153).

The ability of the gonadotrope to interpret varying pulses of GnRH has been the focus of much research, given that differential responses of LH and FSH occur with varying GnRH pulse frequency, both in vivo and in vitro. In ovariectomized rhesus monkeys bearing hypothalamic lesions which reduced circulating LH and FSH to undetectable levels, hourly pulses of GnRH favored LH secretion over FSH, whereas pulses every 3 h favored FSH secretion and caused a decline in LH levels (154). Additional in vivo studies with GnRH deficient men recapitulated this observation (155, 156), as do in vitro studies using pituitary cultures (145–151, 157), with intermediate pulse intervals (30 min–1 h) favoring LHβ transcription and low frequencies (every 3 h) that of FSHβ. Although most work on GnRHR signaling has involved sustained stimulation, similar signaling mechanism appear to be involved in response to pulsatile stimulation, including activation a number of key effectors including Gαq/11, Gαs, and Gαi (41, 79, 158). Downstream of Gαq/11, the Ca2+/calmodulin/calcineurin/NFAT and Raf/MEK/ERK signaling modules are both activated (159, 160) (see below), and gonadotrope ERK has been shown to be essential for reproduction (99) consistent with its role as an effector of pulsatile GnRHR activation in vivo.

The mechanisms by which gonadotropes decode GnRH pulse frequency are largely unknown, despite the fact that this frequency-encoded signal is crucial for the physiology and therapeutic manipulation of the reproductive system (2, 27, 99, 109, 159–162). A key feature of this system is that maximal responses to some effects of GnRH occur with sub-maximal pulse frequencies. In essence this means that there is a bell-shaped frequency-response curve for some effects of GnRH, behavior that has been termed “genuine frequency decoding” (163) to distinguish it from the simpler situation where increasing pulse frequencies elicit increasing responses up to the maximal pulse frequency (i.e., constant stimulation). The bell-shaped frequency-response curve is thought to require more complex systems involving feed-forward or feedback regulation (163) and is exemplified by the non-monotonic relationships seen for effects of GnRH on LHβ or FSHβ expression (as measured using luciferase reporters). However the nature of the negative feedback loop is unclear. It could lie at the level of upstream components of the GnRHR cascade; GnRH causes down-regulation of cell surface GnRHRs (164) and a recent mathematical model of GnRH signaling predicts desensitization due to down-regulation of cell surface GnRHRs, which is more pronounced at higher pulse frequency (165). It cannot however be due to rapid homologous receptor desensitization as type I mammalian GnRHRs do not show this behavior (58). Alternatively, transcription-dependent negative feedback on upstream inputs could occur at high GnRH pulse frequency. This could include GnRHR-mediated induction of regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS)-2 which displays GTPase activating protein activity and is known to inhibit Gαq/11 signaling (166, 167), direct interaction of the GnRHR with SET protein which may inhibit Gαq/11 binding (121), or induction of MAPK phosphatases (MKPs) which would modulate GnRHR-mediated ERK signaling (109). GnRH also causes down-regulation of IP3 receptors (168, 169), and induces expression of calmodulin-dependent small G-protein Kir/Gem (kinase-inducible Ras-like protein/GTP binding protein over-expressed in skeletal muscle), which is known to inhibit Ca2+ channels (145). Finally, the feedback or feed-forward regulatory loops could lie further downstream, within the nucleus. Low pulse frequency causes transient Egr-1 expression, causing expression of co-repressor Nab-2, thus inhibiting LHβ expression. With high GnRH pulse frequencies there is a more sustained increase in Egr-1, which increases LHβ transcription by quenching Nab-2 (162). However, neither upregulation of Nab-1 and Nab-2, or differential expression of Egr-1, were observed in vivo (101). The proteasome has been proposed to play a role in cyclical hormonal responses, by targeting transcription factors for degradation and thus freeing the promoter to enable it to respond to the next pulse of hormone (170) GnRH-mediated LHβ gene expression is dependent on protein degradation via the proteasome, and Egr-1 and SF-1, two key transcription factors for LHβ, are targets of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (171). Targeting transcription factors for degradation would promote gonadotrope sensitivity, allowing more rapid transcriptional responses to changes in GnRH concentration.

There appears to be selective interplay of factors at the Fshb promoter according to pulse frequency: mutation of a CRE site within the FSHβ promoter resulted in loss of preferential GnRH stimulation at low pulse frequencies (161), and low pulse frequencies stimulated PKA activity and levels of phospho-CREB compared to high pulse frequencies (172). AP-1 family members FOS and JUN positively regulate the Fshb promoter and are induced at low GnRH pulse frequencies, whereas SKIL and TGIF1 corepressors negatively regulate the Fshb promoter, and are induced at higher frequencies (173), along with ICER, which antagonizes the stimulatory action of CREB to attenuate FSHβ transcription (161). As well as inducing c-Fos expression, low GnRH pulse frequencies act via the ERK1/2 pathway to cause c-Fos phosphorylation, which extends its half-life, thereby enhancing FSHβ transcription (174).

In order to test for upstream feedback mechanisms during pulsatile GnRH signaling, we have used live cell imaging reporters including an NFAT1c-emerald fluorescent protein (NFAT-EFP) and ERK2-GFP (159, 175). Nuclear translocation of NFAT-EFP provides a readout for elevation of intracellular Ca2+ because the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent activation of calcineurin causes dephosphorylation of cytoplasmic NFAT that exposes a nuclear localization sequence (176). Similarly, activation of ERK causes it to be released from cytoplasmic scaffolds and facilitates protein-protein interaction necessary for nuclear entry, such that the redistribution of ERK2-GFP from the cytoplasm to the nucleus can provide a readout for activation of the Raf/MEK/ERK cascade. In HeLa cells transduced to express type I GnRHR, pulsatile GnRH caused rapid NFAT-EFP and ERK2-GFP nuclear translocation, but with markedly different response kinetics. With 5 min GnRH pulses, ERK2-GFP translocated rapidly to and from the nucleus and the nuclear:cytoplasmic (N:C) ERK2-GFP measure returned to basal values between stimuli, whereas the N:C NFAT-EFP response was slower in onset and offset so that at high pulse frequency the response had not returned to the pre-stimulation value before a subsequent stimulus was added (159, 175). This led to “saw-tooth” or cumulative response, thought to increase signal efficiency with pulsatile stimuli (177). Irrespective of these differences, there was no evidence for desensitization of responses to pulsatile GnRH using these readouts (175) and maximal responses were seen at maximal GnRH pulse frequency. In contrast, maximal effects were seen with sub-maximal pulse frequencies when luciferase reporters containing LHβ or FSHβ promoters were used as experimental readouts. Thus, the bell-shaped frequency-response curve or “genuine frequency decoding” of GnRH pulses is not a specific feature of gonadotropes and can occur in the absence of the negative feedback previously thought to explain it.

The studies outlined above focused on the Ca2+/calmodulin/calcineurin/NFAT and Raf/MEK/ERK pathways because both mediate transcriptional effects of GnRH and both decode pulse frequency in other models (178–183). The promoter regions of gonadotropin genes contain response elements likely to mediate the effects of ERK (i.e., Egr-1 sites) and NFAT (181), and the Raf/MEK/ERK and Ca2+/calmodulin/calcineurin/NFAT cascades are known to act as co-dependent modules in other systems, notably in the control of cardiac myocyte proliferation where ERK and NFAT converge on composite AP-1/NFAT response elements in a number of genes (180, 182). In spite of this, the empirical data provided no explanation for the observed bell-shaped frequency-response relationships so a mathematical approach was taken to explore this further.

We have developed a mathematical model for GnRHR signaling based on a series of ordinary differential equations describing GnRHR occupancy and activation and downstream effectors (27). This differs from earlier models (109, 163, 165, 184–186) in that it incorporates Ca2+/calmodulin/calcineurin/NFAT and Raf/MEK/ERK modules, includes cellular compartmentalization (i.e., nuclear versus cytoplasm) and importantly, lacks upstream negative feedback. This model accurately predicts wet-lab data for activation and nuclear translocation of ERK2-GFP and NFAT-EFP as validated by modeling responses to GnRH pulses at a range of concentrations and frequencies, and therefore these two could be used as inputs to the transcriptome. Using this model we considered the possibility that two transcription factors (TF1 and TF2) act at distinct sites on a common gene promoter named gonadotropin subunit (GSU), a generic term used because this is likely the case for the αGSU, LHβ, and FSHβ gonadotropin subunit genes, as it is for many other ERK and NFAT target genes (178–183). We tested three distinct logic gates for the nature of the action of TF1 and TF2 at the promoter (27). The first is a co-operative GATE that in biological terms could reflect the action of one TF to mediate the interaction between the other TF and the cells transcriptional machinery, or alternatively, the requirement of physical interaction between the two TFs to orientate distant promoter sites and bring them to close proximity for transcription activation. The second is the AND GATE in which both TFs are needed for transcription activation but there is no functional interaction between them, and the third is the OR GATE where either or both TFs can drive transcription but there is again no functional interaction between the two.

This model predicted bell-shaped frequency-response relationships when two TFs act co-operatively. The characteristic feature of maximal response at sub-maximal frequency was never seen with the AND-gate or with the OR-gate, and this behavior was predicted in the absence of negative feedback which is often assumed to underlie it. This modeling also implied that GnRH pulse frequency-response relationship may be plastic, as varying rate constants for transcription factor activation and inactivation, or varying balance of signaling via NFAT and ERK-dependent transcription factors, influenced the pulse frequency predicted to give a maximal response (27).

The importance of the modeling outlined above is that a bell-shaped frequency-response relationship is predicted to be an emergent feature of co-operative and convergent signaling of two signaling pathways. It requires that the pathways have distinct response kinetics and occurs in spite of the fact that individual pathways and pathway components cannot generate this complex relationship (27). It does not, however, establish that the bell-shaped frequency-response relationships seen for transcriptional effects of GnRH are necessarily mediated by convergence of NFAT and ERK-dependent transcription factors. In reality, multiple pathways converge to mediate GnRH effects on transcription, with the relative importance and integration of these inputs being specific for the promoter/enhancer studies (187). In this context, it is of interest that a recent study explored the contribution of Gαs and Gαq signaling for pulsatile GnRH signaling. In this work FRET reporters were used as live cell readouts for activation of the PKA and PLC signaling pathways via the endogenous mouse GnRHR of LβT2 cells (188). This revealed that pulses of GnRH cause pulses of cAMP elevation and PKA activation that are rapid and transient, and do not show measurable desensitization from pulse to pulse (188). This is in accord with the lack of upstream adaptive mechanisms seen with live cell imaging of ERK2-GFP and NFAT-EFP (above). However, the FRET readouts for elevation of Ca2+ and DAG (measures for PLC activation) desensitized rapidly from one pulse to the next (188). This raises the intriguing possibility that co-operative convergent effects of the Gαs and Gαq pathways could mediate GnRH pulse frequency decoding and also that the balance of PKA to PLC signaling varies through a series of GnRH pulses. However, the PLC data are puzzling as desensitization of PLC responses with repeated pulses would be expected to be coupled with desensitization of downstream responses, yet repeat pulses of GnRH can elicit comparable effects on cytoplasmic Ca2+ (189, 190), on gonadotropin secretion (5, 191), and on NFAT-EFP translocation (above). It is also unclear why GnRH-mediated PLC activation would desensitize with repeat GnRH pulses, when PLC-mediated [3H]IP accumulation does not show desensitization with up to 60 min of sustained stimulation (47, 53, 57, 192). Using siRNA and bacterial toxins to specifically perturb individual G proteins in LβT2 cells, Choi et al. demonstrated that FSHβ expression was dependent on Gαq, whereas Gαs-mediated LHβ transcription and suppressed that of FSHβ (193). Inhibinα was identified as a Gαs dependent GnRH-induced autocrine/paracrine factor which suppresses FSHβ transcription. Its transcriptional profile contrasts with that of FSHβ, being induced by high pulse frequencies, and therefore its absence at low pulse frequencies may explain the preference for FSHβ transcription.

Autocrine and Paracrine Regulation of Gonadotropes

Given the crucial role of GnRH in reproduction, it is not surprising that most work on gonadotrope cell signaling has focused on its mode of action. However, gonadotropes are receptive to various other extracellular stimuli, including the gonadal steroids estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, which as well as acting centrally to influence GnRH secretion, also act directly on the pituitary to modulate GnRH effects on gonadotropes. In addition to GnRH, gonadotropes are targets for a large number of GPCR-activating ligands (194). These include oxytocin, endothelin-1, galanin, β-endorphin, neuropeptide Y, nucleotides, and pituitary adenylyl cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP), a highly conserved member of the vasoactive peptide (VIP)-secretin-glucagon peptide superfamily.

Here we highlight some additional signaling pathways key to cyclic nucleotide signaling in the gonadotrope.

Pituitary Adenylyl Cyclase Activating Polypeptide

Pituitary adenylyl cyclase activating polypeptide was originally isolated from sheep hypothalamic extracts based on its ability to stimulate cAMP production by rat pituitary cell cultures (195). It is widely distributed in the nervous, immune, gastrointestinal, cardiac, and endocrine systems (195, 196). Two isoforms have been identified, a 38 amino acid form (PACAP38) and C-terminally truncated 27 amino acid form (PACAP27), with PACAP38 accounting for 90% of the protein in most tissues (194–198). The PACAP peptides have 68% amino acid homology with VIP but are 1000 times more potent in their ability to stimulate cAMP (196).

Three receptors are activated by PACAP; VPAC1, and VPAC2 which have similar affinity for VIP and PACAP, and PAC1, which is highly selective for PACAP (197–200). PAC1 receptors have the potential to couple directly to both Gαs and Gαq/11 and exist as multiple splice variants due to alternative splicing of two exons in the third intracellular loop (hip and hop) and are named null (neither hip nor hop), hip, hop1, hop2, hiphop1, and hiphop2 (194, 198, 200–202). Early work showed that (for most PAC1 variants) PACAP38 and PACAP27 had comparable potency for stimulation of cAMP production, whereas PACAP38 was much more potent than PACAP27 for stimulation of IP accumulation (203).

Within the anterior pituitary, the major secretory cells and folliculo-stellate cells all express at least one type of PACAP receptor (200, 204). Various PAC1 receptor forms predominate in the rat pituitary and gonadotrope cell lines (205), and in these cells PACAP activates PAC1, causing a Gαs-mediated stimulation of cAMP production and a Gαq/11-mediated increase in [Ca2+]i (194, 197, 200, 206–211). PACAP regulates gonadotropin secretion and expression of signature genes in gonadotropes either acting alone, or by modulating GnRH effects (194, 197, 200, 210, 212–218). PACAP can act alone or synergistically with GnRH to stimulate LH and FSH production (216, 219), although the effect of PACAP on LH secretion is modest compared to that of GnRH (215). Low pulse frequencies of GnRH promote PACAP and PAC1R expression compared to high pulse frequencies (220). In LβT2 cells, high frequencies of PACAP pulses increase LHβ transcription, whereas low frequencies promote that of FSHβ (as seen with GnRH pulses) (221). In addition PACAP and PAC1R expression increase with lower frequencies of PACAP pulses (221, 222). The action of GnRH in the regulation of gonadotropin subunit expression is enhanced by the presence of PAC1Rs (223). At present the mechanisms by which PACAP and its receptor contribute to FSHβ and LHβ expression are unknown, it may act to increase GnRHR expression via a cAMP mediated pathway (224).

Pituitary adenylyl cyclase activating polypeptide increases follistatin expression by gonadotropes and folliculo-stellate cells (211, 225, 226), and therefore may modulate activin signaling in the pituitary (197). PAC1 receptor activation causes much greater elevation of cAMP than GnRH does in gonadotrope-derived cell lines (200, 208, 209), and GnRH actually causes a PKC-mediated inhibition of PAC1-mediated cAMP elevation (208, 227). Therefore, if gonadotropes are exposed to stimulatory concentrations of (local or hormonal) PACAP in vivo, GnRH pulses could actually inhibit rather than stimulate cAMP production (208).

Natruiretic Peptides, Nitric Oxide, and Guanylyl Cyclases

The natriuretic peptides atrial-, B-type, and C-type natriuretic peptides (ANP, BNP, and CNP respectively) act via cell surface guanylyl cyclase containing receptors to stimulate cGMP accumulation, which causes activation of protein kinase G (PKG) and cyclic nucleotide gated ion channels (Figure 1) (199). These are single trans-membrane enzymes which are thought to act as homodimers (199, 228). There are three subtypes of receptor, NPRA (GC-A) which has high affinity for ANP and BNP, NPRB (GC-B), which is selective for CNP, and the NPRC (GC-C) receptor which binds all three peptides and acts predominantly as a clearance receptor (229). The effects of ANP and BNP on hemodynamic and cardiovascular regulation are well documented (229, 230). The physiological roles of CNP are less clear, although a critical role in endochondral ossification is evident (231). CNP is expressed in LH positive cells of the anterior pituitary (232, 233), and female mice with either the CNP (Nppc) or GC-B (Nprb) genes deleted are infertile (231, 234).

CNP stimulates cGMP accumulation in GnRH neurons (235), pituitary gonadotropes (236), and endocrine cells of the testis, ovaries, placenta, and uterus (237–244), implying widespread roles of CNP in the hypothalamo-pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis. In gonadotrope-derived cell lines, CNP activates the αGSU promoter (233), however it has no effect on LH secretion or GnRH-stimulated LH secretion (228, 233, 245). GnRH causes rapid PKC-mediated inhibition of CNP-stimulated cGMP accumulation in αT3-1 cells (228, 236), and may stimulate CNP expression, by transcriptional regulation of the Nppc gene (233). However, little is known about the actions of cGMP in the pituitary, so the physiological relevance of pituitary CNP/NPRA signaling remains unknown.

Gonadotropes also express the enzyme responsible for the generation of nitric oxide (NO), NO synthase (NOS) (246). The NOS enzyme family is composed of three major isoforms, neuronal NOS (nNOS), inducible NOS (iNOS), and endothelial NOS (eNOS). These enzymes convert l-arginine to l-citrulline, producing NO, an important signaling molecule involved in a variety of physiological and pathological processes (247). It exerts physiological effects by activation of soluble guanylyl cyclases to generate cGMP (248). nNOS and eNOS are expressed constitutively and activated by Ca2+/calmodulin, whereas iNOS is Ca2+-independent (129, 194). In the anterior pituitary, nNOS has been specifically detected in the folliculo-stellate cells and gonadotropes (137, 249). GnRH stimulates the activity and expression of nNOS in gonadotropes (136, 137, 250) and this likely explains the increase in nNOS expression and activity observed at proestrous (136). GnRH may activate the nNOS promoter via cAMP-dependent activation of a CRE in the GnRH-responsive region of the nNOS promoter (251, 252). Alternatively it may act via SF-1, which acts on a nuclear hormone receptor binding site on the nNOS promoter in pituitary gonadotropes to stimulate transcription (253).

Nitric oxide itself inhibits GnRH-stimulated LH secretion, with the NOS inhibitor MeArg markedly potentiating GnRH-induced LH secretion, and the NO donor SNP significantly reducing it (246, 254, 255). GnRH, LH, and FSH release are decreased in chronic NO deficiency (256, 257), and in humans treatment with an NOS inhibitor can reduce GnRH-stimulated LH and FSH release (258). The effects of NO on gonadotropin secretion remain rather controversial [see Ref. (194) for discussion of stimulatory and inhibitory effects]. Intriguingly, NO donors stimulate LH and FSH release in a cGMP-independent manner (254, 259) implying that these effects reflect regulation of NO targets other than soluble guanylyl cyclases.

Conclusion

Type I mammalian GnRHRs of pituitary gonadotropes signal primarily via Gq/11. Uniquely, they have no C-terminal tail and therefore do not elicit the C-tail dependent and heterotrimeric G-protein independent signaling seen with many other GPCRs. These features could ensure that the type I mammalian GnRHR of pituitary gonadotropes (e.g., the receptors that mediate central control of reproduction in humans) faithfully transduce the portal blood GnRH signal into PLC activation in the target cells, and this could arguably confer selective advantage by (i.e., facilitating the pre-ovulatory gonadotropin surge). Nevertheless, there is ample evidence that GnRHRs can activate other heterotrimeric G-proteins and that they do so in a cell context-dependent manner (44, 77, 111, 112, 115, 120, 208, 260–262). Notably, they apparently activate Gi in some hormone-dependent cancer cell models and activate Gq/11, Gs, and Gi in GT1-7 neurons. Early work in primary cultures of pituitary cells revealed that GnRH increases cAMP production (112, 113) but this would not necessarily reflect Gs activation and could even involve regulated cAMP production in cells other than gonadotropes. Subsequent work revealed little or no effect of GnRH on cAMP production in the gonadotrope-derived αT3-1 cell line (120, 208, 216) as opposed to the stimulatory effects seen in the more mature LβT2 gonadotrope cell line (77, 111). Such studies do not really address the fundamental question of physiological role. Thus, although it is well established that PLC-mediated effects on cytoplasmic Ca2+ and PKC influence exocytotic secretion of gonadotropins and transcriptional effects of GnRH, the relevance of GnRH effects on cAMP (and cGMP) production are much less clear. In this review we have highlighted two areas that may prove important in resolving this issue. The first is that paracrine or autocrine mechanisms exist for regulation of cyclic nucleotide production. Notably, PACAP has pronounced effects on cAMP production in gonadotropes and gonadotrope-derived cell lines, and the possibility exists that the modest stimulatory effects of GnRH pale into insignificance in gonadotropes exposed to PACAP. The second is that GnRH is secreted in pulses and very little is known about signaling of pulsatile GnRH via anything other than Gq/11. Here, a key feature is that maximal effects of GnRH are often elicited at sub-maximal GnRH pulse frequency and mathematical modeling has revealed that such non-monotonic frequency-response curves could reflect co-operative activity of two (or more) convergent signaling pathways. This was explored for the Ca2+/calmodulin/calcineurin/NFAT and Raf/MEK/ERK pathways but the same logic could equally apply to either (or both) of these pathways acting together with the Gs/AC/cAMP/PKA pathway. In this regard it is of interest that GnRHR activation actually reduces PACAP-stimulated cAMP production and CNP-stimulated cGMP production in αT3-1 cells (208, 236) raising the question of whether GnRH pulses are stimulatory or inhibitory for these pathways in vivo. Clearly, a great deal is yet to be learned about cyclic nucleotide signaling in gonadotropes and how the signaling network integrates inputs via PLC, AC and GC.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded Project Grants from MRC (93447) and the BBSRC (J014699).

Abbreviations

Ca2+, calcium; cAMP, cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate; EFP, emerald fluorescent protein; EGF, epidermal growth factor; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase, here used to denote ERK1 and ERK2; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GFP, green fluorescent protein; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone also known as GnRH I; GnRHR II, gonadotropin-releasing hormone II, also known as chicken GnRH; GnRHR, GnRH receptor; GPCR, G-protein coupled receptor; GRK, G-protein coupled receptor kinase; IP, inositol phosphate; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LH, luteinizing hormone; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK, MAPK/ERK kinase; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T-cells; NO, nitric oxide; PKC, protein kinase C; PLC, phospholipase C.

References

- 1.Cheng CK, Leung PC. Molecular biology of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-I, GnRH-Ii, and their receptors in humans. Endocr Rev (2005) 26:283–306 10.1210/er.2003-0039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciccone NA, Kaiser UB. The biology of gonadotroph regulation. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes (2009) 16:321–7 10.1097/MED.0b013e32832d88fb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Millar RP, Lu ZL, Pawson AJ, Flanagan CA, Morgan K, Maudsley SR. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors. Endocr Rev (2004) 25:235–75 10.1210/er.2003-0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sealfon SC, Weinstein H, Millar RP. Molecular mechanisms of ligand interaction with the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Endocr Rev (1997) 18:180–205 10.1210/er.18.2.180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stojilkovic SS, Catt KJ. Novel aspects of GnRH-induced intracellular signaling and secretion in pituitary gonadotrophs. J Neuroendocrinol (1995) 7:739–57 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1995.tb00711.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, Chadwick W, Park SS, Zhou Y, Silver N, Martin B, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor system: modulatory role in aging and neurodegeneration. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets (2010) 9:651–60 10.2174/187152710793361559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cattanach BM, Iddon CA, Charlton HM, Chiappa SA, Fink G. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone deficiency in a mutant mouse with hypogonadism. Nature (1977) 269:338–40 10.1038/269338a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mason AJ, Hayflick JS, Zoeller RT, Young WS, III, Phillips HS, Nikolics K, et al. A deletion truncating the gonadotropin-releasing hormone gene is responsible for hypogonadism in the hpg mouse. Science (1986) 234:1366–71 10.1126/science.3024317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Roux N, Young J, Misrahi M, Genet R, Chanson P, Schaison G, et al. A family with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and mutations in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. N Engl J Med (1997) 337:1597–602 10.1056/NEJM199711273372205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernald RD, White RB. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone genes: phylogeny, structure, and functions. Front Neuroendocrinol (1999) 20:224–40 10.1006/frne.1999.0181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider JS, Rissman EF. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone II: a multi-purpose neuropeptide. Integr Comp Biol (2008) 48:588–95 10.1093/icb/icn018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White SA, Kasten TL, Bond CT, Adelman JP, Fernald RD. Three gonadotropin-releasing hormone genes in one organism suggest novel roles for an ancient peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1995) 92:8363–7 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamamoto N, Oka Y, Amano M, Aida K, Hasegawa Y, Kawashima S. Multiple gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-immunoreactive systems in the brain of the dwarf gourami, Colisa lalia: immunohistochemistry and radioimmunoassay. J Comp Neurol (1995) 355:354–68 10.1002/cne.903550303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gothilf Y, Munoz-Cueto JA, Sagrillo CA, Selmanoff M, Chen TT, Kah O, et al. Three forms of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in a perciform fish (Sparus aurata): complementary deoxyribonucleic acid characterization and brain localization. Biol Reprod (1996) 55:636–45 10.1095/biolreprod55.3.636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parhar IS, Soga T, Sakuma Y. Quantitative in situ hybridization of three gonadotropin-releasing hormone-encoding mRNAs in castrated and progesterone-treated male tilapia. Gen Comp Endocrinol (1998) 112:406–14 10.1006/gcen.1998.7143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okubo K, Amano M, Yoshiura Y, Suetake H, Aida K. A novel form of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2000) 276:298–303 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amano M, Oka Y, Yamanome T, Okuzawa K, Yamamori K. Three GnRH systems in the brain and pituitary of a pleuronectiform fish, the barfin flounder Verasper moseri. Cell Tissue Res (2002) 309:323–9 10.1007/s00441-002-0594-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vickers ED, Laberge F, Adams BA, Hara TJ, Sherwood NM. Cloning and localization of three forms of gonadotropin-releasing hormone, including the novel whitefish form, in a salmonid, Coregonus clupeaformis. Biol Reprod (2004) 70:1136–46 10.1095/biolreprod.103.023846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuo MW, Lou SW, Postlethwait J, Chung BC. Chromosomal organization, evolutionary relationship, and expression of zebrafish GnRH family members. J Biomed Sci (2005) 12:629–39 10.1007/s11373-005-7457-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohamed JS, Thomas P, Khan IA. Isolation, cloning, and expression of three prepro-GnRH mRNAs in Atlantic croaker brain and pituitary. J Comp Neurol (2005) 488:384–95 10.1002/cne.20596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pandolfi M, Munoz Cueto JA, Lo Nostro FL, Downs JL, Paz DA, Maggese MC, et al. GnRH systems of Cichlasoma dimerus (Perciformes, Cichlidae) revisited: a localization study with antibodies and riboprobes to GnRH-associated peptides. Cell Tissue Res (2005) 321:219–32 10.1007/s00441-004-1055-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soga T, Ogawa S, Millar RP, Sakuma Y, Parhar IS. Localization of the three GnRH types and GnRH receptors in the brain of a cichlid fish: insights into their neuroendocrine and neuromodulator functions. J Comp Neurol (2005) 487:28–41 10.1002/cne.20519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohamed JS, Khan IA. Molecular cloning and differential expression of three GnRH mRNAs in discrete brain areas and lymphocytes in red drum. J Endocrinol (2006) 188:407–16 10.1677/joe.1.06423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan K, Millar RP. Evolution of GnRH ligand precursors and GnRH receptors in protochordate and vertebrate species. Gen Comp Endocrinol (2004) 139:191–7 10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conn PM, Crowley WF., Jr Gonadotropin-releasing hormone and its analogs. Annu Rev Med (1994) 45:391–405 10.1146/annurev.med.45.1.391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belchetz P, Dufy B, Knobil E. Identification of inhibitory and stimulatory control of prolactin secretion in the rhesus monkey. Neuroendocrinology (1978) 27:32–8 10.1159/000122798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsaneva-Atanasova K, Mina P, Caunt CJ, Armstrong SP, McArdle CA. Decoding GnRH neurohormone pulse frequency by convergent signalling modules. J R Soc Interface (2012) 9:170–82 10.1098/rsif.2011.0215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schally AV. LH-RH analogues: I. Their impact on reproductive medicine. Gynecol Endocrinol (1999) 13:401–9 10.3109/09513599909167587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stojilkovic SS, Reinhart J, Catt KJ. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors: structure and signal transduction pathways. Endocr Rev (1994) 15:462–99 10.1210/er.15.4.462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruf F, Fink MY, Sealfon SC. Structure of the GnRH receptor-stimulated signaling network: insights from genomics. Front Neuroendocrinol (2003) 24:181–99 10.1016/S0091-3022(03)00027-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeong KH, Kaiser UB. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone regulation of gonadotropin biosynthesis and secretion. In: Knobil E, Neill JD. editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. 3rd ed San Diego, CA: Elsevier; (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheung LW, Wong AS. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone: GnRH receptor signaling in extrapituitary tissues. FEBS J (2008) 275:5479–95 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06677.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgan K, Sellar R, Pawson AJ, Lu ZL, Millar RP. Bovine and ovine gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-II ligand precursors and type II GnRH receptor genes are functionally inactivated. Endocrinology (2006) 147:5041–51 10.1210/en.2006-0222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eidne KA, Flanagan CA, Harris NS, Millar RP. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-binding sites in human breast cancer cell lines and inhibitory effects of GnRH antagonists. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (1987) 64:425–32 10.1210/jcem-64-3-425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Limonta P, Montagnani Marelli M, Moretti RM. LHRH analogues as anticancer agents: pituitary and extrapituitary sites of action. Expert Opin Investig Drugs (2001) 10:709–20 10.1517/13543784.10.4.709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finch AR, Green L, Hislop JN, Kelly E, McArdle CA. Signaling and antiproliferative effects of type I and II gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors in breast cancer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2004) 89:1823–32 10.1210/jc.2003-030787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan K, Stewart AJ, Miller N, Mullen P, Muir M, Dodds M, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor levels and cell context affect tumor cell responses to agonist in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res (2008) 68:6331–40 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montagnani Marelli M, Moretti RM, Mai S, Januszkiewicz-Caulier J, Motta M, Limonta P. Type I gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor mediates the antiproliferative effects of GnRH-II on prostate cancer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2009) 94:1761–7 10.1210/jc.2008-1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fost C, Duwe F, Hellriegel M, Schweyer S, Emons G, Grundker C. Targeted chemotherapy for triple-negative breast cancers via LHRH receptor. Oncol Rep (2011) 25:1481–7 10.3892/or.2011.1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Limonta P, Montagnani Marelli M, Mai S, Motta M, Martini L, Moretti RM. GnRH receptors in cancer: from cell biology to novel targeted therapeutic strategies. Endocr Rev (2012) 33(5):784–811 10.1210/er.2012-1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kraus S, Naor Z, Seger R. Intracellular signaling pathways mediated by the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor. Arch Med Res (2001) 32:499–509 10.1016/S0188-4409(01)00331-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pawson AJ, McNeilly AS. The pituitary effects of GnRH. Anim Reprod Sci (2005) 88:75–94 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2005.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conn PM, Huckle WR, Andrews WV, McArdle CA. The molecular mechanism of action of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) in the pituitary. Recent Prog Horm Res (1987) 43:29–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McArdle CA. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor signaling: biased and unbiased. Mini Rev Med Chem (2012) 12:841–50 10.2174/138955712800959080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horn F, Bilezikjian LM, Perrin MH, Bosma MM, Windle JJ, Huber KS, et al. Intracellular responses to gonadotropin-releasing hormone in a clonal cell line of the gonadotrope lineage. Mol Endocrinol (1991) 5:347–55 10.1210/mend-5-3-347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McArdle CA, Huckle WR, Conn PM. Phorbol esters reduce gonadotrope responsiveness to protein kinase C activators but not to Ca2+-mobilizing secretagogues. Does protein kinase C mediate gonadotropin-releasing hormone action? J Biol Chem (1987) 262:5028–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McArdle CA, Franklin J, Green L, Hislop JN. Signalling, cycling and desensitisation of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone receptors. J Endocrinol (2002) 173:1–11 10.1677/joe.0.1730001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rispoli LA, Nett TM. Pituitary gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor: structure, distribution and regulation of expression. Anim Reprod Sci (2005) 88:57–74 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2005.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bockaert J, Marin P, Dumuis A, Fagni L. The “magic tail” of G protein-coupled receptors: an anchorage for functional protein networks. FEBS Lett (2003) 546:65–72 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00453-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pierce KL, Lefkowitz RJ. Classical and new roles of beta-arrestins in the regulation of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci (2001) 2:727–33 10.1038/35094577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heding A, Vrecl M, Bogerd J, McGregor A, Sellar R, Taylor PL, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors with intracellular carboxyl-terminal tails undergo acute desensitization of total inositol phosphate production and exhibit accelerated internalization kinetics. J Biol Chem (1998) 273:11472–7 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blomenrohr M, Bogerd J, Leurs R, Goos H. Differences in structure-function relations between nonmammalian and mammalian GnRH receptors: what we have learnt from the African catfish GnRH receptor. Prog Brain Res (2002) 141:87–93 10.1016/S0079-6123(02)41086-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davidson JS, Wakefield IK, Millar RP. Absence of rapid desensitization of the mouse gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Biochem J (1994) 300(Pt 2):299–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Finch AR, Caunt CJ, Armstrong SP, McArdle CA. Agonist-induced internalization and downregulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol (2009) 297:C591–600 10.1152/ajpcell.00166.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hislop JN, Madziva MT, Everest HM, Harding T, Uney JB, Willars GB, et al. Desensitization and internalization of human and Xenopus gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors expressed in alphaT4 pituitary cells using recombinant adenovirus. Endocrinology (2000) 141:4564–75 10.1210/en.141.12.4564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hislop JN, Everest HM, Flynn A, Harding T, Uney JB, Troskie BE, et al. Differential internalization of mammalian and non-mammalian gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors. Uncoupling of dynamin-dependent internalization from mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J Biol Chem (2001) 276:39685–94 10.1074/jbc.M104542200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen ZP, Kratzmeier M, Levy A, McArdle CA, Poch A, Day A, et al. Evidence for a role of pituitary ATP receptors in the regulation of pituitary function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1995) 92:5219–23 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McArdle CA, Davidson JS, Willars GB. The tail of the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone receptor: desensitization at, and distal to, G protein-coupled receptors. Mol Cell Endocrinol (1999) 151:129–36 10.1016/S0303-7207(99)00024-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vrecl M, Anderson L, Hanyaloglu A, McGregor AM, Groarke AD, Milligan G, et al. Agonist-induced endocytosis and recycling of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor: effect of beta-arrestin on internalization kinetics. Mol Endocrinol (1998) 12:1818–29 10.1210/me.12.12.1818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pawson AJ, Katz A, Sun YM, Lopes J, Illing N, Millar RP, et al. Contrasting internalization kinetics of human and chicken gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors mediated by C-terminal tail. J Endocrinol (1998) 156:R9–12 10.1677/joe.0.156R009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pawson AJ, Faccenda E, Maudsley S, Lu ZL, Naor Z, Millar RP. Mammalian type I gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors undergo slow, constitutive, agonist-independent internalization. Endocrinology (2008) 149:1415–22 10.1210/en.2007-1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Castro-Fernandez C, Conn PM. Regulation of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (GnRHR) by RGS proteins: role of the GnRHR carboxyl-terminus. Mol Cell Endocrinol (2002) 191:149–56 10.1016/S0303-7207(02)00082-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hanyaloglu AC, Vrecl M, Kroeger KM, Miles LE, Qian H, Thomas WG, et al. Casein kinase II sites in the intracellular C-terminal domain of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor and chimeric gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors contribute to beta-arrestin-dependent internalization. J Biol Chem (2001) 276:18066–74 10.1074/jbc.M009275200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heding A, Vrecl M, Hanyaloglu AC, Sellar R, Taylor PL, Eidne KA. The rat gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor internalizes via a beta-arrestin-independent, but dynamin-dependent, pathway: addition of a carboxyl-terminal tail confers beta-arrestin dependency. Endocrinology (2000) 141:299–306 10.1210/en.141.1.299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hislop JN, Caunt CJ, Sedgley KR, Kelly E, Mundell S, Green LD, et al. Internalization of gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors (GnRHRs): does arrestin binding to the C-terminal tail target GnRHRs for dynamin-dependent internalization? J Mol Endocrinol (2005) 35:177–89 10.1677/jme.1.01809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Acharjee S, Maiti K, Soh JM, Im WB, Seong JY, Kwon HB. Differential desensitization and internalization of three different bullfrog gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors. Mol Cells (2002) 14:101–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ronacher K, Matsiliza N, Nkwanyana N, Pawson AJ, Adam T, Flanagan CA, et al. Serine residues 338 and 339 in the carboxyl-terminal tail of the type II gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor are critical for beta-arrestin-independent internalization. Endocrinology (2004) 145:4480–8 10.1210/en.2004-0075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Caunt CJ, Finch AR, Sedgley KR, McArdle CA. Seven-transmembrane receptor signalling and ERK compartmentalization. Trends Endocrinol Metab (2006) 17:276–83 10.1016/j.tem.2006.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. The role of beta-arrestins in the termination and transduction of G-protein-coupled receptor signals. J Cell Sci (2002) 115:455–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kendall RT, Luttrell LM. Diversity in arrestin function. Cell Mol Life Sci (2009) 66:2953–73 10.1007/s00018-009-0088-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luttrell LM, Roudabush FL, Choy EW, Miller WE, Field ME, Pierce KL, et al. Activation and targeting of extracellular signal-regulated kinases by beta-arrestin scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2001) 98:2449–54 10.1073/pnas.041604898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Multifaceted roles of beta-arrestins in the regulation of seven-membrane-spanning receptor trafficking and signalling. Biochem J (2003) 375:503–15 10.1042/BJ20031076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Caunt CJ, Finch AR, Sedgley KR, McArdle CA. GnRH receptor signalling to ERK: kinetics and compartmentalization. Trends Endocrinol Metab (2006) 17:308–13 10.1016/j.tem.2006.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Caunt CJ, Finch AR, Sedgley KR, Oakley L, Luttrell LM, McArdle CA. Arrestin-mediated ERK activation by gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors: receptor-specific activation mechanisms and compartmentalization. J Biol Chem (2006) 281:2701–10 10.1074/jbc.M507242200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hawes BE, Barnes S, Conn PM. Cholera toxin and pertussis toxin provoke differential effects on luteinizing hormone release, inositol phosphate production, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor binding in the gonadotrope: evidence for multiple guanyl nucleotide binding proteins in GnRH action. Endocrinology (1993) 132:2124–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stanislaus D, Ponder S, Ji TH, Conn PM. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor couples to multiple G proteins in rat gonadotrophs and in GGH3 cells: evidence from palmitoylation and overexpression of G proteins. Biol Reprod (1998) 59:579–86 10.1095/biolreprod59.3.579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu F, Usui I, Evans LG, Austin DA, Mellon PL, Olefsky JM, et al. Involvement of both G(q/11) and G(s) proteins in gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor-mediated signaling in L beta T2 cells. J Biol Chem (2002) 277:32099–108 10.1074/jbc.M203639200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grundker C, Volker P, Emons G. Antiproliferative signaling of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone in human endometrial and ovarian cancer cells through G protein alpha(I)-mediated activation of phosphotyrosine phosphatase. Endocrinology (2001) 142:2369–80 10.1210/en.142.6.2369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Naor Z. Signaling by G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR): studies on the GnRH receptor. Front Neuroendocrinol (2009) 30:10–29 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stojilkovic SS, Iida T, Merelli F, Torsello A, Krsmanovic LZ, Catt KJ. Interactions between calcium and protein kinase C in the control of signaling and secretion in pituitary gonadotrophs. J Biol Chem (1991) 266:10377–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Iida T, Stojilkovic SS, Izumi S, Catt KJ. Spontaneous and agonist-induced calcium oscillations in pituitary gonadotrophs. Mol Endocrinol (1991) 5:949–58 10.1210/mend-5-7-949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Leong DA, Thorner MO. A potential code of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-induced calcium ion responses in the regulation of luteinizing hormone secretion among individual gonadotropes. J Biol Chem (1991) 266:9016–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hansen JR, McArdle CA, Conn PM. Relative roles of calcium derived from intra- and extracellular sources in dynamic luteinizing hormone release from perifused pituitary cells. Mol Endocrinol (1987) 1:808–15 10.1210/mend-1-11-808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stojilkovic SS, Tomic M, Kukuljan M, Catt KJ. Control of calcium spiking frequency in pituitary gonadotrophs by a single-pool cytoplasmic oscillator. Mol Pharmacol (1994) 45:1013–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mulvaney JM, Roberson MS. Divergent signaling pathways requiring discrete calcium signals mediate concurrent activation of two mitogen-activated protein kinases by gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J Biol Chem (2000) 275:14182–9 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roberson MS, Misra-Press A, Laurance ME, Stork PJ, Maurer RA. A role for mitogen-activated protein kinase in mediating activation of the glycoprotein hormone alpha-subunit promoter by gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Mol Cell Biol (1995) 15:3531–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Harris D, Chuderland D, Bonfil D, Kraus S, Seger R, Naor Z. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase and c-Src, but not Jun N-terminal kinase, are involved in basal and gonadotropin-releasing hormone-stimulated activity of the glycoprotein hormone alpha-subunit promoter. Endocrinology (2003) 144:612–22 10.1210/en.2002-220690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Weck J, Fallest PC, Pitt LK, Shupnik MA. Differential gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation of rat luteinizing hormone subunit gene transcription by calcium influx and mitogen-activated protein kinase-signaling pathways. Mol Endocrinol (1998) 12:451–7 10.1210/me.12.3.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fowkes RC, King P, Burrin JM. Regulation of human glycoprotein hormone alpha-subunit gene transcription in LbetaT2 gonadotropes by protein kinase C and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2. Biol Reprod (2002) 67:725–34 10.1095/biolreprod67.3.725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Harris D, Bonfil D, Chuderland D, Kraus S, Seger R, Naor Z. Activation of MAPK cascades by GnRH: ERK and Jun N-terminal kinase are involved in basal and GnRH-stimulated activity of the glycoprotein hormone LHbeta-subunit promoter. Endocrinology (2002) 143:1018–25 10.1210/en.143.3.1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu F, Austin DA, Mellon PL, Olefsky JM, Webster NJ. GnRH activates ERK1/2 leading to the induction of c-fos and LHbeta protein expression in LbetaT2 cells. Mol Endocrinol (2002) 16:419–34 10.1210/me.16.3.419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Call GB, Wolfe MW. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone activates the equine luteinizing hormone beta promoter through a protein kinase C/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Biol Reprod (1999) 61:715–23 10.1095/biolreprod61.3.715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kanasaki H, Bedecarrats GY, Kam KY, Xu S, Kaiser UB. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse frequency-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways in perifused LbetaT2 cells. Endocrinology (2005) 146:5503–13 10.1210/en.2004-1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bonfil D, Chuderland D, Kraus S, Shahbazian D, Friedberg I, Seger R, et al. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase, Jun N-terminal kinase, p38, and c-Src are involved in gonadotropin-releasing hormone-stimulated activity of the glycoprotein hormone follicle-stimulating hormone beta-subunit promoter. Endocrinology (2004) 145:2228–44 10.1210/en.2003-1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vasilyev VV, Pernasetti F, Rosenberg SB, Barsoum MJ, Austin DA, Webster NJ, et al. Transcriptional activation of the ovine follicle-stimulating hormone-beta gene by gonadotropin-releasing hormone involves multiple signal transduction pathways. Endocrinology (2002) 143:1651–9 10.1210/en.143.5.1651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang Y, Fortin J, Lamba P, Bonomi M, Persani L, Roberson MS, et al. Activator protein-1 and smad proteins synergistically regulate human follicle-stimulating hormone beta-promoter activity. Endocrinology (2008) 149:5577–91 10.1210/en.2008-0220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kowase T, Walsh HE, Darling DS, Shupnik MA. Estrogen enhances gonadotropin-releasing hormone-stimulated transcription of the luteinizing hormone subunit promoters via altered expression of stimulatory and suppressive transcription factors. Endocrinology (2007) 148:6083–91 10.1210/en.2007-0407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ferris HA, Walsh HE, Stevens J, Fallest PC, Shupnik MA. Luteinizing hormone beta promoter stimulation by adenylyl cyclase and cooperation with gonadotropin-releasing hormone 1 in transgenic mice and LBetaT2 cells. Biol Reprod (2007) 77:1073–80 10.1095/biolreprod.107.064139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bliss SP, Miller A, Navratil AM, Xie J, McDonough SP, Fisher PJ, et al. ERK signaling in the pituitary is required for female but not male fertility. Mol Endocrinol (2009) 23:1092–101 10.1210/me.2009-0030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Burger LL, Haisenleder DJ, Dalkin AC, Marshall JC. Regulation of gonadotropin subunit gene transcription. J Mol Endocrinol (2004) 33:559–84 10.1677/jme.1.01600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Burger LL, Haisenleder DJ, Aylor KW, Marshall JC. Regulation of Lhb and Egr1 gene expression by GNRH pulses in rat pituitaries is both c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)- and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-dependent. Biol Reprod (2009) 81:1206–15 10.1095/biolreprod.109.079426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Xie J, Bliss SP, Nett TM, Ebersole BJ, Sealfon SC, Roberson MS. Transcript profiling of immediate early genes reveals a unique role for activating transcription factor 3 in mediating activation of the glycoprotein hormone alpha-subunit promoter by gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Mol Endocrinol (2005) 19:2624–38 10.1210/me.2005-0056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Roberson MS, Zhang T, Li HL, Mulvaney JM. Activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Endocrinology (1999) 140:1310–8 10.1210/en.140.3.1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Haisenleder DJ, Burger LL, Walsh HE, Stevens J, Aylor KW, Shupnik MA, et al. Pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation of gonadotropin subunit transcription in rat pituitaries: evidence for the involvement of Jun N-terminal kinase but not p38. Endocrinology (2008) 149:139–45 10.1210/en.2007-1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yokoi T, Ohmichi M, Tasaka K, Kimura A, Kanda Y, Hayakawa J, et al. Activation of the luteinizing hormone beta promoter by gonadotropin-releasing hormone requires c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase. J Biol Chem (2000) 275:21639–47 10.1074/jbc.M910252199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kraus S, Benard O, Naor Z, Seger R. c-Src is activated by the epidermal growth factor receptor in a pathway that mediates JNK and ERK activation by gonadotropin-releasing hormone in COS7 cells. J Biol Chem (2003) 278:32618–30 10.1074/jbc.M303886200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Levi NL, Hanoch T, Benard O, Rozenblat M, Harris D, Reiss N, et al. Stimulation of Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) by gonadotropin-releasing hormone in pituitary alpha T3-1 cell line is mediated by protein kinase C, c-Src, and CDC42. Mol Endocrinol (1998) 12:815–24 10.1210/me.12.6.815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Coss D, Hand CM, Yaphockun KK, Ely HA, Mellon PL. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase is critical for synergistic induction of the FSH(beta) gene by gonadotropin-releasing hormone and activin through augmentation of c-Fos induction and Smad phosphorylation. Mol Endocrinol (2007) 21:3071–86 10.1210/me.2007-0247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lim S, Pnueli L, Tan JH, Naor Z, Rajagopal G, Melamed P. Negative feedback governs gonadotrope frequency-decoding of gonadotropin releasing hormone pulse-frequency. PLoS One (2009) 4:e7244. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mayer SI, Willars GB, Nishida E, Thiel G. Elk-1, Creb, and MKP-1 regulate Egr-1 expression in gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulated gonadotrophs. J Cell Biochem (2008) 105:1267–78 10.1002/jcb.21927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lariviere S, Garrel G, Simon V, Soh JW, Laverriere JN, Counis R, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone couples to 3’,5’-cyclic adenosine-5’-monophosphate pathway through novel protein kinase Cdelta and -epsilon in LbetaT2 gonadotrope cells. Endocrinology (2007) 148:1099–107 10.1210/en.2006-1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Borgeat P, Chavancy G, Dupont A, Labrie F, Arimura A, Schally AV. Stimulation of adenosine 3’:5’-cyclic monophosphate accumulation in anterior pituitary gland in vitro by synthetic luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1972) 69:2677–81 10.1073/pnas.69.9.2677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Naor Z, Koch Y, Chobsieng P, Zor U. Pituitary cyclic AMP production and mechanism of luteinizing hormone release. FEBS Lett (1975) 58:318–21 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80288-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Liu F, Austin DA, Webster NJ. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone-desensitized LbetaT2 gonadotrope cells are refractory to acute protein kinase C, cyclic Amp, and calcium-dependent signaling. Endocrinology (2003) 144:4354–65 10.1210/en.2003-0204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Arora KK, Krsmanovic LZ, Mores N, O’Farrell H, Catt KJ. Mediation of cyclic AMP signaling by the first intracellular loop of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. J Biol Chem (1998) 273:25581–6 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lin X, Janovick JA, Conn PM. Mutations at the consensus phosphorylation sites in the third intracellular loop of the rat gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor: effects on receptor ligand binding and signal transduction. Biol Reprod (1998) 59:1470–6 10.1095/biolreprod59.6.1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Oh DY, Song JA, Moon JS, Moon MJ, Kim JI, Kim K, et al. Membrane-proximal region of the carboxyl terminus of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (GnRHR) confers differential signal transduction between mammalian and nonmammalian GnRHRs. Mol Endocrinol (2005) 19:722–31 10.1210/me.2004-0220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Conn PM, Morrell DV, Dufau ML, Catt KJ. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone action in cultured pituicytes: independence of luteinizing hormone release and adenosine 3’,5’-monophosphate production. Endocrinology (1979) 104:448–53 10.1210/endo-104-2-448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Theoleyre M, Berault A, Garnier J, Jutisz M. Binding of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (LH-RH) to the pituitary plasma membranes and the problem of adenylate cyclase stimulation. Mol Cell Endocrinol (1976) 5:365–77 10.1016/0303-7207(76)90019-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Grosse R, Schmid A, Schoneberg T, Herrlich A, Muhn P, Schultz G, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor initiates multiple signaling pathways by exclusively coupling to G(q/11) proteins. J Biol Chem (2000) 275:9193–200 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Avet C, Garrel G, Denoyelle C, Laverriere JN, Counis R, Cohen-Tannoudji J, et al. SET protein interacts with intracellular domains of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor and differentially regulates receptor signaling to cAMP and calcium in gonadotrope cells. J Biol Chem (2013) 288:2641–54 10.1074/jbc.M112.388876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Andrade J, Quinn J, Becker RZ, Shupnik MA. AMP-activated protein kinase is a key intermediary in GnRH-stimulated LHbeta gene transcription. Mol Endocrinol (2013) 27:828–39 10.1210/me.2012-1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]