Abstract

Vector-borne parasites cause major human diseases of the developing world, including malaria, human African trypanosomiasis, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, filariasis, and schistosomiasis. Although the life cycles of these parasites were defined over 100 years ago, the strategies they use to optimize their successful transmission are only now being understood in molecular terms. Parasites are now known to monitor their environment in both their host and vector and in response to other parasites. This allows them to adapt their developmental cycles and to counteract any unfavorable conditions they encounter. Here, I review the interactions that parasites engage in with their hosts and vectors to maximize their survival and spread.

Our understanding of the important steps in a parasite’s life cycle is usually dominated by where they cause disease. This is inevitably their human and animal hosts, where the study of the strategies that parasites use to ensure survival and proliferation have shaped our thinking of immune system function, as well as of eukaryotic cell and molecular biology. From the parasite’s perspective, in fact, this might not be the most challenging part of their life history, because overcoming the immune system leaves them in a nutritious and equable environment. Less predictable challenges come when parasites leave their host, aiming to colonize new hosts. Although some parasites achieve this, for example, by releasing resistant dormant stages that are directly transferred to new hosts in food or water, many parasites rely on vectors for their transmission (Fig. 1). However, parasites do not simply evade host immunity until a passing vector picks them up but instead use exquisitely controlled mechanisms of environmental sensing and developmental regulation to ensure their transmission. This imperative has dominated the evolution of many parasites to the extent that the drive for transmission influences almost every aspect of their biology, including interactions within their vector, often a blood-feeding arthropod. Here, I review our state of understanding of how parasites optimize their transmission potential and overcome the challenges they encounter as they passage through their vectors. Initially, I address how parasites prepare for their uptake by a vector, by optimizing production of specialized transmissible forms, which often exhibit arrested development and sensitivity to the environmental cues that signal passage to the vector. Next, I address how parasites detect their exit from the mammalian host and rapidly adapt to enable survival and proliferation in their invertebrate vector. Lastly, I discuss how vectors combat their invasion by parasites and how parasites have evolved strategies to manipulate their vector to maximize their transmission.

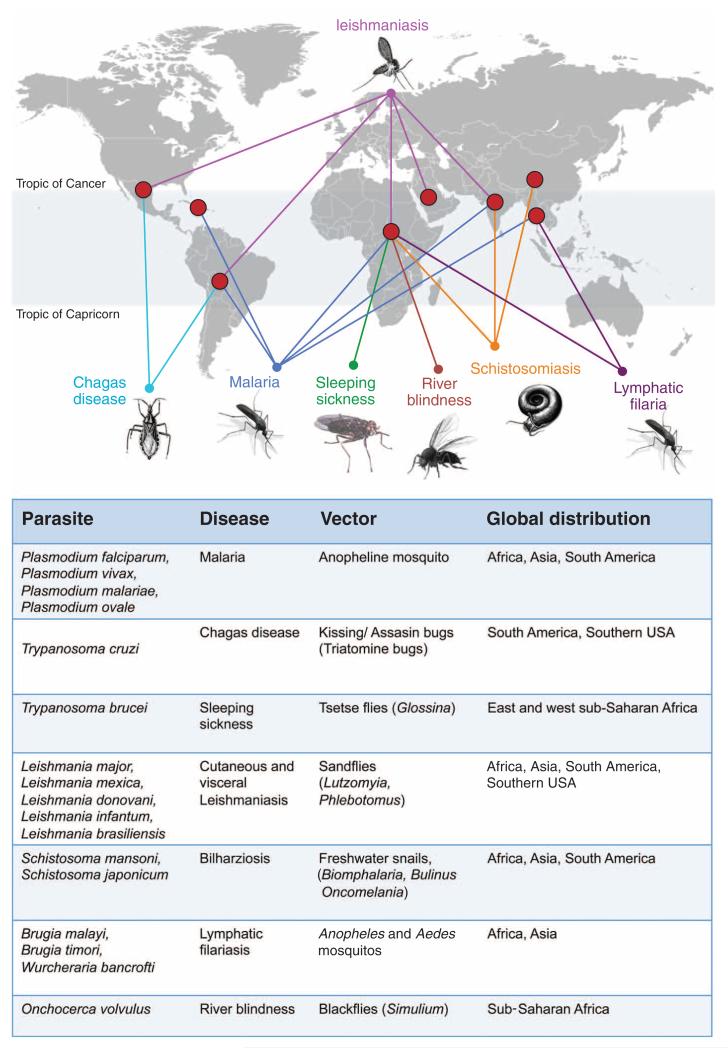

Fig. 1. The global distribution of vector-borne human diseases.

The individual parasites and their vectors are indicated in the table, as are the diseases they cause and their main geographical distributions.1

Preparing for Transmission: How Do Parasites Maximize Their Chances of Success?

Once parasites become established in a mammalian host, they must prolong their survival and maximize their likelihood of transmission to a new host. These might be complementary objectives, but often they require a trade-off that is managed by cell-type differentiation to generate developmental forms specialized for each role. Simplistically, a consistent proportion of each cell type might be sufficient to achieve transmission; however, the host is a dynamic environment, where variable exposure to immune responses, competing parasite strains, and the stresses associated with infection or drug exposure can generate opposing pressures on survival and transmission. Consequently, parasites monitor their environment and respond by altering their investment in different developmental forms. For example, in the malaria parasite Plasmodium, asexual stages predominate to ensure that the population of infected red blood cells is maximized. Subsequently, the development of sexual stage gametocytes prepares the parasite for transmission (1). However, developmental investment shows plasticity under different host conditions, such that the proportion (2) and even the sex ratio (3) of transmissible gametocytes can change in response to stress or competition. This interaction with the host-modulated environment is also seen in some parasitic helminths, where the hormonal context and exposure to CD4+ cells drive schistosome blood-fluke development (4), and in filarial nematodes, where experimental exposure to a more aggressive immune environment promotes the production of transmissible microfilaria (5).

Parasites also interact with related parasites to maximize their probability of transmission. For example, Trypanosoma brucei, which causes human African trypanosomiasis controls its investment in transmissible “stumpy” forms by monitoring its cell density in the host bloodstream (6), a phenomenon akin to bacterial quorum sensing. It does this apparently by releasing a signal, termed stumpy induction factor (SIF). SIF has so far eluded purification perhaps because it represents a complex mixture of small molecules or because the bioassays for its detection have been insufficiently robust. Nonetheless, the potential importance of this unidentified factor is clear because a variability between SIF production and turnover in different hosts could influence the number of transmissible parasites at a given cell density. Because African trypanosomes infect a wide range of mammals, which also act as reservoirs for human infection, this variation would affect the zoonotic potential of the parasite. Moreover, if cell density signaling is effective between T. brucei strains, as appears to be the case from one laboratory study (6), then a conflict between parasites in a co-infection could be established. This conflict has the potential to select different strains that differ in their production or sensitivity to SIF or that are optimized to different hosts, thus affecting their probability of transmission in different contexts.

As well as their ability to sense and respond to their local environment, a further characteristic feature of transmission stages for both metazoan and protozoan parasites is the capacity to arrest their development. Frequently, parasites stop proliferation before undergoing the differentiation responses that generate transmissible forms. This strategy is similar to that seen in other eukaryotic cells that become quiescent in order to tolerate harsh environmental changes. Developmental arrest has the obvious advantage of limiting the risk of lethal cell division errors that can occur during DNA replication or chromosome segregation. Crucially, for parasites, it can also prevent uncontrolled proliferation in the host, which if unchecked could lead to host damage or death and so limit transmission potential.

Unlike many quiescent eukaryotic cells, the arrested development of parasite transmission stages is usually irreversible. A consequence is that transmission stages must be stringently regulated to prevent premature differentiation in the mammalian host, a response that would be lethal to the parasite. In African trypanosomes, such forward development is tightly repressed by a tyrosine phosphatase, which holds the parasites poised for differentiation (7). The arrested transmission stages must also be able to persist long enough to favor their uptake by a vector to continue the life cycle. Several mechanisms achieve this in different parasite groups. In T. brucei, one strategy is to use the hydrodynamic flow generated by parasite swimming to sweep surface-bound antibody toward the parasite posterior, where it is internalized via the flagellar pocket (8). Generalized immunosuppression is another common strategy used by parasites to potentially prolong the longevity of transmission stages. For example, in filarial infections serpins specifically secreted by transmissible microfilariae are able to modulate host immune function (9).

Clearly, parasites optimize their probability of transmission by interacting with the network of signals operating between the host, kin, and competing parasites (Fig. 2). We assume complex sensing mechanisms have evolved, but we know little about them; for instance, how is Plasmodium gametocytogenesis initiated or modulated? What is SIF? How are competitors or immune factors recognized and responded to in different parasite groups? Despite functional investigations on individual signaling components that affect transmissibility and the complete cataloging of conventional signaling molecules identified in genome analyses, there is almost no coherent understanding of the molecular pathways that regulate parasite development. An essential current goal, therefore, is to assemble these pathways. Understanding the molecules and mechanisms that control the interactions between parasites and hosts, and among parasites themselves, also offers the prospect of approaches to disease control that manipulate the parasite’s transmission potential.

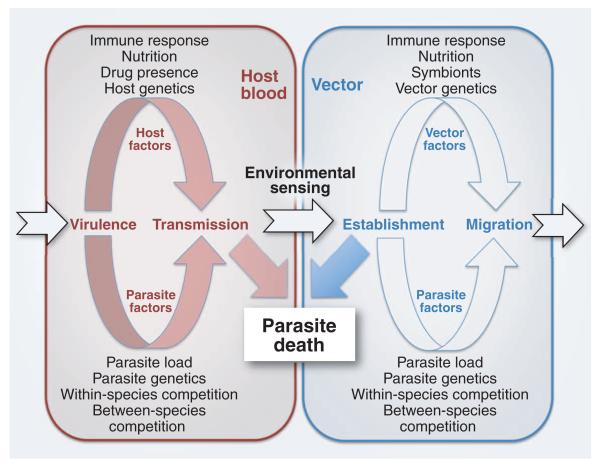

Fig. 2. Factors that influence the development of parasites as they pass through their mammalian host or vector.

In each case, host- and parasite-moderated conditions can determine the developmental fate of the parasite. During transmission between the mammalian host and the vector and during establishment in the vector, there is often a significant amount of parasite death.

Once Transmitted, How Do Parasites Rapidly Adapt to Their Vector?

The uptake of parasites by their vector requires that they perceive environmental change and adapt immediately to the new host. Unsurprisingly, temperature change is a major determinant of environmental sensing when moving from a mammalian host to an invertebrate vector (10). However, temperature alone is not sufficient, and at least two signals are usually required to precipitate differentiation, perhaps providing a failsafe to prevent the risk of premature development in the mammalian host. For Plasmodium, a component of the mosquito eye-pigment synthetic pathway, xanthurenic acid, is a key environmental trigger (11) when sensed in the context of both low temperature and raised pH. Temperature is also an important cue for Leishmania spp. and Trypanosoma cruzi during their development, whereas for African trypanosomes, low temperature enables the detection of citrate in the blood meal, which then triggers differentiation (12). Once the stimulus is perceived, signaling cascades are activated, mediated through cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate in Plasmodium (13) or a phosphatase cascade in T. brucei (14), for example.

Once the adaptive mechanisms are triggered, the parasites can tolerate rapid changes in the blood meal environment and evade invertebrate immune mechanisms. For such a rapid-response capability, a common strategy is to hold pre-made mRNAs ready for translation, rather than relying on new gene transcription and then protein synthesis. In Plasmodium, mRNAs are held silent and stable in gametocytes in P granules, storage compartments in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells that ensure that mRNAs are kept apart from the active translational machinery (15). Plasmodium P granules contain an RNA helicase, DOZI (16), that ensures mRNAs are stable and not translated until required, that is, upon ookinete formation after ingestion by mosquitoes. A similar strategy also operates in American (17) and African (18) trypanosomes as protection against stress and probably in preparation for transmission. In T. brucei, transmissible stumpy forms are quiescent until they are taken up by tsetse flies,; whereupon translational repression is released, and, coupled with new mRNA synthesis, rapid adaptations to assist survival in the vector are effected (19). The signals governing the silencing of the translationally quiescent mRNA pool are not well characterized and are unlikely to be simple motifs given the widespread repression of many genes at this life-cycle stage. Nonetheless, the recruitment to P granules of specific mRNAs required during transmission appears to be an important mechanism for holding mRNAs poised for action. Specificity in gene regulation is also expected for the small subset of genes that escape generalized translational repression operating in transmission stages. The identification of this subset will be particularly exciting because these are the molecules most likely to be required for detecting and enacting the earliest events of differentiation in the vector. Characterization of their regulatory control is also necessary to understand the mechanisms by which parasites prepare for transmission.

In addition to protein synthesis, protein turnover is important for restructuring parasites as they adapt to their vector or prepare for transfer back to a mammalian host. In Leishmania parasites, an arsenal of protein degradation enzymes concentrated in the lysosome contributes to cellular remodeling. The lysosome is also the focus of autophagic events that turn over cellular proteins and organelles as the parasites alter gene expression and metabolic capacity. A similar phenomenon occurs in T. brucei, where the lysosome expands massively during establishment of the procyclic forms in the tsetse midgut. The expansion contributes to the replacement of stage-specific metabolic enzymes contained within the glycosomes (20), which are peroxisome-like organelles that compartmentalize the parasite’s glycolytic enzymes and which show different compositions in different life-cycle stages. This replacement enables a rapid rewiring of the parasite’s metabolism during the transition from one life-cycle stage to the next, which is essential as the parasite moves from a glucose-rich mammalian blood environment to the proline-rich environment of the insect midgut.

Parasites usually change morphology as they establish in their invertebrate vector. Hence, the Plasmodium ookinete is quite different from either the game-tocytes or the zygote. The ovoid shape of ookinetes matches the basic apicomplexan form, which potentially assists their attachment to, and migration through, the mosquito gut wall. Similarly, the very short flagellum of the intracellular amastigote Leishmania rapidly extends when the parasite is taken up by a sandfly, allowing motility of the differentiated promastigote in the vector’s gut. Morphological changes can also serve other functions. In T. brucei the epimastigote flagellum allows attachment to the salivary gland of the tsetse, whereas in Leishmania and T. brucei the flagellum may provide an important sensory function, which helps the parasite to monitor its environment during development (21).

Changes in the position of the mitochondrial genome (kinetoplast) with respect to the cell nucleus are also common in kinetoplastid parasites, including African and American trypanosomes and Leishmania sp., although the reasons are unclear. Because the kinetoplast is intimately associated with the base of the flagellum, it may help to govern the overall length of the exposed flagellum and influence its sensory capacity. In T. brucei, kinetoplast repositioning may relate to the different organizational needs of the parasite’s protein trafficking apparatus in the tsetse fly, where the delivery of the bloodstream variant surface glycoprotein coat to the cell surface is no longer an imperative. Alternatively, the kineto-plast may change position to assist the function of the closely located flagellar pocket or to meet distinct cell-cycle requirements in different life-cycle stages (22, 23). Indeed, the cell cycle of many parasites is intimately linked to their morphology, and specific cell organization must apparently be established before embarking on cell division during differentiation in the vector.

From the analysis of the events that accompany differentiation as parasites enter their vector, it is clear that they undergo a precisely regulated and hierarchical developmental program. Many distinct cellular events have to be temporally or functionally coordinated, requiring careful control of the timing of gene expression events and the coassembly of new or modified cellular structures. How these different events are coordinated is poorly understood, despite the mapping of coincident gene expression changes and the characterization of distinct cellular events in the developmental transitions of several parasites, including Plasmodium and kinetoplastid parasites.

Analyzing, the extent to which different events are linked and depend on each other during the extensive remodeling that occurs as parasites adapt to their new environment is important, not just to design interventions for disease control but also for understanding eukaryotic developmental biology and the coordination of functions in different organelles. In future, a more coherent picture of developmental events and their coordinated control should emerge to replace the piecemeal analysis of individual molecules that have been generated thus far.

Is There a Conflict Between Parasites and Their Vectors?

The immune evasion tactics of parasites in their mammalian host have been the focus of most research in the field; however, vector-borne parasites are also challenged by the immune defences of invertebrates (Fig. 3). Invertebrate responses consist of innate factors and cell-mediated immunity, both of which affect parasites as they establish and are sustained in their vectors. Because invertebrate immune responses share evolutionary origins with mammalian immune systems, parasites can encounter similar types of challenge. For example, in their snail vector, schistosomes are targeted by cytokines like macrophage inhibitory factor, which is homologous to the mammalian cytokine that acts against a broad range of parasites (24). After ingestion in blood, Plasmodium and filarial nematodes migrate through the insect’s gut lining into the hemocoel, causing tissue damage and generating an antimicrobial response that can limit infection. In Plasmodium, ookinetes migrate through the midgut epithelium and are recognized by pathogen recognition receptors, thioester-containing protein 1, leucine-rich immune molecule 1, and Anopheles Plasmodium-responsive leucine-rich repeat protein 1-C, which operate to induce serine protease cascades that produce antiparasitic effects, including melanization (25), a process that targets both protozoa and helminths. Mosquitoes also express Toll and Imd receptors, which in turn stimulate antimicrobial peptide (i.e., defensins, attacins, gambicin, and cecropins) synthesis from the fat body. The immune responses generated by Plasmodium in concert with the community of bacteria that proliferate in a blood meal can have important consequences for parasite establishment (25). This interaction is proposed to generate a Plasmodium-directed immune memory in the hemocoel granulocyte population that limits subsequent transmission events by other parasite genotypes (26).

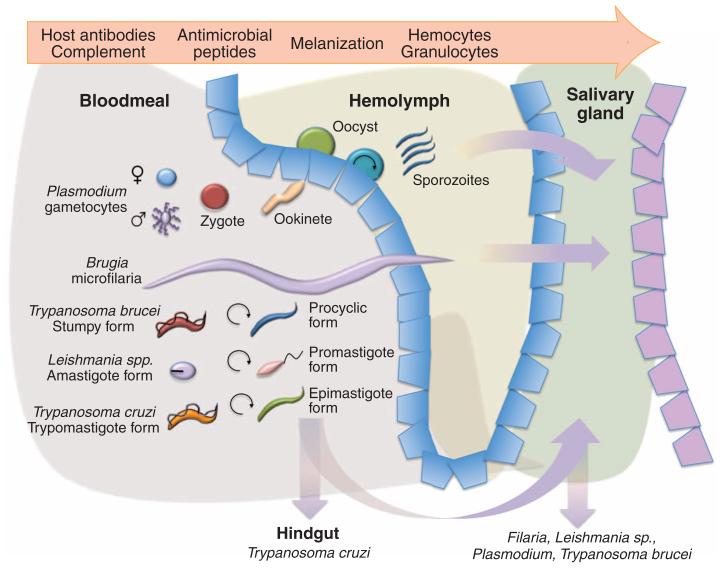

Fig. 3. Routes of transmission of different parasite groups through an arthropod vector.

Plasmodium male and female gametocytes fuse to generate a zygote, which then matures to an ookinete that penetrates the gut lining of the mosquito vector. This develops into an oocyst, within which sporozoites develop. Sporozoites are released and migrate to the mosquito salivary gland, where they are infective to a mammalian host when the mosquito seeks a blood meal. For helminths, microfilariae are ingested during blood feeding by mosquitoes (Wurcheraria and Brugia) or blackflies (Onchocerca). The worms then migrate through the hemocoel, eventually reaching the proboscis and salivary glands, where they can be transmitted to a new host. For kinetoplastid parasites, ingested nonproliferative transmissible forms develop into proliferative forms that establish in the alimentary canal of their vector. For T. brucei, the parasites then migrate via the proventriculum of the tsetse fly to the salivary glands, where they attach and multiply as epimastigote forms before forming infective metacyclic forms. For T. cruzi and Leishmania, the parasites multiply in the gut of the kissing bug and sandfly vectors, respectively, before maturing into infective forms (trypomastigote forms in T. cruzi or promastigote metacyclic forms in Leishmania) in either the hind gut or pharyngeal valve, respectively. T. cruzi are transmitted by expulsion during bug defecation, parasites being rubbed into the bite wound. The challenges faced by the parasite within its invertebrate vector are indicated above the diagram.

Like Plasmodium, procyclic-form African trypanosomes stimulate the production of an array of antimicrobial peptides in their vector, the tsetse fly (27), plus an unusual factor known as TsetseEP (28), composed of glutamic acid–proline (EP) repeats. This structure is similar to major surface proteins on the procyclic midgut form of the parasites known as EP procyclin, and depletion of TsetseEP promotes trypanosome establishment (29). Interestingly, this effect is not exclusively based on the sequence similarity between the two molecules, because TsetseEP also protects against Trypanosoma congolense, which expresses a distinct procyclin type lacking EP repeats. Reactive oxygen species are also important determinants of tsetse resistance to trypanosomes. It appears that in combination the different defense strategies are highly effective given the low frequency of trypanosome-infected tsetses in the field.

For both nematode and Plasmodium infections in mosquitoes, the interactions between different vectors and parasite strains in the field, compounded by the associated microbial communities, can generate complex effects on vectorial competence (30). Here, analysis of vector immune gene sequence evolution within populations, as a signature of selection generated by parasite infection (31), offers exciting possibilities for pinpointing key molecular interactions between parasites and vectors in the field.

Although vectors mount substantial responses to limit parasite transmission, the interaction between parasites and vectors is not unidirectional. Indeed, as well as invertebrate immunity having evolved to combat parasitic invasion, parasites have evolved to manipulate their vectors to their own advantage. Perhaps the best known example is Leishmania parasites, which secrete a plug composed of filamentous phosphoproteoglycan in the gut of their sandfly vector. The presence of the plug stimulates the vector to increase its mammalian biting frequency and hence promotes the parasite’s transmission efficiency (32). A similar phenomenon occurs during Plasmodium invasion of the mosquito salivary glands. Invasion of the glands by the parasite’s sporozoites reduces apyrase levels in saliva, which seems to increase the mosquito biting frequency and hence the number of hosts bitten by Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes (33). Likewise, trypanosome infection reduces salivary protein levels and increases probing frequency of infected tsetse flies (34), increasing the probability of effective parasite passage. Except in the case of Leishmania parasites, the mechanisms by which parasites alter probing frequency are not understood and nor is the process by which, for example, salivary protein production is reduced. Although fascinating, these are very difficult questions to answer experimentally.

The combination of challenges encountered by parasites within their vector causes bottlenecks that restrict the parasite genotypes in different tissues of the vector. Oberle et al. (35) recently quantified the frequency of marked lineages of African trypanosomes during tsetse transmission and discovered that few parasites successfully traverse from the midgut to the salivary gland, at least in laboratory infections. This bottleneck would be of little consequence in clonal populations; however, T. brucei can undergo sexual exchange in the salivary gland. Although sex apparently occurs infrequently in the field, its impact may be significant because different parasite lines show genetically determined virulence traits (36). Recombination in a mixed tsetse infection could generate new parasite lines with quite different disease progression in mammals.

When sex occurs in parasites within the arthropod vector, site and mechanisms can differ. For apicomplexan parasites such as Plasmodium and the cattle parasite Theileria, zygote formation occurs upon entry into the vector, whereas in African trypanosomes, sexual exchange precedes exit. Do these differences reflect where selection pressure for diversity is exerted, or are they simply an evolutionary relic? The mechanism can also vary. Hence, Mendelian inheritance has been established for Plasmodium and T. brucei, but for T. cruzi there is cell fusion of diploid parents and subsequent genetic loss (37), similar to the parasexual events of some fungi. It is not yet clear whether the recent discovery (38) of sexual exchange in Leishmania parasites in sandflies is conventionally Mendelian, but, like sex in the African trypanosomes, it is a rare event.

Outlook

The transmission cycles of vector-borne parasites are now among the most actively studied areas of parasite biology. This impetus has been enabled by developments in parasite culture, genetic analysis through genome sequencing, and through progress in the genetic manipulation of both the parasite and vector. Moreover, the increased sensitivity of detection for both transcripts and proteins at stages in the parasite life cycle where there are severe limitations in the biological material available have enabled previously cryptic events, such as sexual exchange, to be observed and studied. When combined with our increasing understanding of the immune mechanisms operating in invertebrate vectors, analyses of the detailed interactions between parasites and their vectors are now tractable (Box 1).

Box 1. Key research questions relating to the transmission of vector-borne parasites.

How do parasites monitor host status?

How do parasites detect and respond to related and unrelated parasites?

How do parasites detect and transduce developmental cues?

How do parasites coordinate cellular processes to achieve differention during vector colonization?

How do parasites counteract or avoid vector immune defenses?

How do parasites achieve directional migration in their vectors?

How do parasites influence vector behavior and fitness?

What genetic factors govern host-parasite-vector tropism?

Several themes are emerging. First, parasites do not passively transit through their life cycles in either the mammalian host or their vector. Instead, they are constantly surveying their environment, and it will be important to identify the signals and signaling pathways that they exploit and to understand the implications of these for their life history strategies.

Second, it is clear that parasites manipulate their vectors. Impaired feeding responses can improve the probability of parasite transmission and demand an understanding of how vector feeding behavior can be manipulated by the parasite. Here, the increasing sensitivity of mass spectrometry may allow parasite-released products to be identified within subcompartments of the vector and candidate molecular manipulators identified.

Third, parasites are likely to have fitness costs for their vectors. Filarial nematodes, for example, create considerable tissue damage as they migrate through their insect vector, with an impact on their longevity. Nonetheless, most parasites take time to mature within their vectors before becoming transmissible to a new host. Consequently, it is important that their vectors survive for long enough for parasites to mature and are not so disadvantaged that transmission is unlikely. Hence, parasites may minimize their impact sufficiently to maximize their probability of transmission or to generate compensatory fitness benefits, for example, by reducing the reproductive burden or increasing the defensive behavior of their vectors (33). These effects are difficult to study and hard to quantitate, but nonetheless likely to have important consequences for transmission in the field.

Lastly, the co-evolution of parasites and their vectors has generated quite precise specificity in vectorial competence. This complicates genetic and functional studies of parasite-vector interactions, where the available laboratory strains of parasites and vectors may not be well matched. Nonetheless, understanding the restrictions of vectorial competence for a parasite has major implications for the transmission of parasites in different geospatial settings, directly affecting the likely success of particular intervention programs. Further, it is an essential component of predicting the probability of an expansion in a parasite’s host range and the consequent emergence of new disease foci, as evidenced by the escape of Trypanosoma evansi from a dependence on tsetse flies, allowing it to spread through Asia and South America (39). For parasites with different ranges of host and vector specificity, the rapid developments in the tools for population genomic analyses of parasites and their vectors and hosts will prove highly informative for understanding parasite transmission potential in the field.

Although only a few details of the molecular events underlying parasite development within their vectors have been determined, transmission represents a vulnerable and attractive point of attack for preventing disease spread. Here, genetic determinants of parasite refractoriness, the impact of bacterial symbionts, and the mechanisms of parasite environmental sensing and developmental adaptation all offer important potential targets. Very often, the key molecules in the parasite will be highly specific and distinct from those in related parasites with different developmental cycles or vectors. For this reason, the most interesting discoveries may emerge from the analysis of the ~60% or more of parasite genes for which no function can yet be assigned. Hence, the development of effective forward genetic screens or high-throughput reverse genetic screens represents exciting progress.

Nevertheless, strategies focused on manipulating the developmental cycles of parasites may have limited impact or even counterproductive effects. For example, the investment in transmission stages does not necessarily reflect the potential for transmission, particularly if low numbers of transmissible forms are sufficient for successful passage and establishment in the vector. Several studies have also revealed how parasites can modify their life histories in response to intervention, either to enhance transmission potential, virulence in the host, or pathology. Hence, mechanistic approaches alone may not be sufficient to predict the outcome of therapeutic strategies. Instead, the integration of molecular study and evolutionary and mathematical analysis of an intervention’s likely implication are necessary to devise effective and safe approaches to preventing disease transmission.

Acknowledgments

Work in K.M.’s laboratory is funded by the Wellcome Trust. I thank my colleagues in the Centre for Immunity, Infection and Evolution for many useful discussions and insights that have informed several of the ideas in this review, and J. Allen and R. Carter for comments on the manuscript. I apologize to all those whose research could not be individually cited due to space constraints.

Footnotes

Erratum. (Post date 22 April 2011) In figure 1, a parasite name was misspelled; the correct name is Wuchereria bancrofti.

References

- 1.Baker DA. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2010;172:57. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackinnon MJ, Read AF. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Ser. B. 2004;359:965. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reece SE, Drew DR, Gardner A. Nature. 2008;453:609. doi: 10.1038/nature06954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies SJ, et al. Science. 2001;294:1358. doi: 10.1126/science.1064462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babayan SA, Read AF, Lawrence RA, Bain O, Allen JE. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vassella E, Reuner B, Yutzy B, Boshart M. J. Cell Sci. 1997;110:2661. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.21.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szöor B, Wilson J, McElhinney H, Tabernero L, Matthews KR. J. Cell Biol. 2006;175:293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engstler M, et al. Cell. 2007;131:505. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewitson JP, Grainger JR, Maizels RM. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2009;167:1. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang J, McCutchan TF. Nature. 2002;418:742. doi: 10.1038/418742a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Billker O, et al. Nature. 1998;392:289. doi: 10.1038/32667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean SD, Marchetti R, Kirk K, Matthews KR. Nature. 2009;459:213. doi: 10.1038/nature07997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McRobert L, et al. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szöor B, Ruberto I, Burchmore R, Matthews KR. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1306. doi: 10.1101/gad.570310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mair GR, et al. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000767. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mair GR, et al. Science. 2006;313:667. doi: 10.1126/science.1125129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassola A, De Gaudenzi JG, Frasch AC. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;65:655. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer S, et al. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:3002. doi: 10.1242/jcs.031823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fenn K, Matthews KR. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2007;10:539. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herman M, Pérez-Morga D, Schtickzelle N, Michels PA. Autophagy. 2008;4:294. doi: 10.4161/auto.5443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rotureau B, Morales MA, Bastin P, Späth GF. Cell. Microbiol. 2009;11:710. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson DR, Sherwin T, Ploubidou A, Byard EH, Gull K. J. Cell Biol. 1995;128:1163. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Briggs LJ, et al. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:1641. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baeza Garcia A, et al. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001115. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yassine H, Osta MA. Cell. Microbiol. 2010;12:1. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodrigues J, Brayner FA, Alves LC, Dixit R, Barillas-Mury C. Science. 2010;329:1353. doi: 10.1126/science.1190689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roditi I, Lehane MJ. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008;11:345. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chandra M, Liniger M, Tetley L, Roditi I, Barry JD. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;34:1163. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haines LR, Lehane SM, Pearson TW, Lehane MJ. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000793. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erickson SM, et al. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009;3:e529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obbard DJ, Welch JJ, Kim KW, Jiggins FM. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers ME, Ilg T, Nikolaev AV, Ferguson MA, Bates PA. Nature. 2004;430:463. doi: 10.1038/nature02675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurd H. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2003;48:141. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Den Abbeele J, Caljon G, De Ridder K, De Baetselier P, Coosemans M. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000926. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oberle M, Balmer O, Brun R, Roditi I. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001023. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrison LJ, et al. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009;3:e557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaunt MW, et al. Nature. 2003;421:936. doi: 10.1038/nature01438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akopyants NS, et al. Science. 2009;324:265. doi: 10.1126/science.1169464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen RE, Simpson L, Englund PT. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:428. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]