Abstract

Background

Recent research suggests that the Bayesian paradigm may be useful for modeling biases in epidemiological studies, such as those due to misclassification and missing data. We used Bayesian methods to perform sensitivity analyses for assessing the robustness of study findings to the potential effect of these two important sources of bias.

Methods

We used data from a study of the joint associations of radiotherapy and smoking with primary lung cancer among breast cancer survivors. We used Bayesian methods to provide an operational way to combine both validation data and expert opinion to account for misclassification of the two risk factors and missing data. For comparative purposes we considered a “full model” that allowed for both misclassification and missing data, along with alternative models that considered only misclassification or missing data, and the naïve model that ignored both sources of bias.

Results

We identified noticeable differences between the four models with respect to the posterior distributions of the odds ratios that described the joint associations of radiotherapy and smoking with primary lung cancer. Despite those differences we found that the general conclusions regarding the pattern of associations were the same regardless of the model used. Overall our results indicate a nonsignificantly decreased lung cancer risk due to radiotherapy among nonsmokers, and a mildly increased risk among smokers.

Conclusions

We described easy to implement Bayesian methods to perform sensitivity analyses for assessing the robustness of study findings to misclassification and missing data.

Keywords: Bayesian methods, sensitivity analysis, bias, misclassification, missing data

Introduction

Several epidemiological studies have investigated the joint association of radiotherapy and smoking with primary lung cancer among breast cancer survivors [1–4]. These studies have found evidence for a statistical interaction between these two risk factors, i.e. a deviation from the multiplicative model for the joint effects of the two risk factors. Using data from the Swedish Cancer Registry (SCR) including approximately 141,000 women diagnosed with breast cancer between 1958 and 1997, Prochazka et al. (2002) found evidence of an interaction between radiotherapy and smoking [1]. A related follow-up case-only study involving 182 women from the SCR, diagnosed with breast cancer between 1958 and 2000, found an effect of radiotherapy on subsequent primary lung cancer only among smokers [2]. A case-control study that included 280 primary lung cancer cases, diagnosed with breast cancer between 1960 and 1997, and 300 frequency-matched controls, randomly selected from the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center patient population, also found an effect of radiotherapy only among smokers [3]. Additional confirmation of the interaction between radiotherapy and smoking was shown in a population-based case-control study (113 cases and 364 controls) using data for women diagnosed between 1965 and 1989 from the Connecticut Tumor Registry [4]. The results of these four epidemiological studies provide strong evidence for the need to thoroughly investigate the joint associations of radiotherapy and smoking with primary lung cancer among breast cancer survivors.

Although all the previously described studies had the misclassification of radiotherapy and/or smoking as potential limitations, none of them attempted to formally adjust for this bias. Indeed, variables such as radiotherapy and smoking are frequently misclassified [5–7]. In this paper we used a combination of external validation data and informative priors to correct for misclassification of radiotherapy and smoking by applying a Bayesian approach. Specifically, we used data from [3] to illustrate how sensitivity analyses may be performed to evaluate the impact of misclassification of the risk factors on the results. We did not consider the presence of outcome misclassification, given that lung cancer tumors were excluded from our data if there was ambiguity with respect to being primary or metastatic disease. An additional complication with the data was that a number of subjects had missing information on at least one variable. Our Bayesian approach also accounted for missing data under the common assumption that the missing data mechanism was missing at random (MAR), i.e. that the probability that a variable is observed depends only on the values of the other variables which have been observed but not on the value of the missing variable [8].

Materials and Methods

The data used for this sensitivity analysis is from the case-control study described in [3]. The 280 cases were females, aged 30–89 years old, diagnosed with breast cancer between 1960 and 1997, and diagnosed with primary lung cancer at least 6 months after the breast cancer diagnosis. The 300 controls were randomly selected from the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center breast cancer patient population during the same time period (n=37,000), and were frequency-matched to the cases on age at the breast cancer diagnosis (5 year intervals), ethnicity, and year of breast cancer diagnosis (5 years intervals). The data for this retrospective, hospital-based, chart review study was obtained through the review of medical records by trained abstractors. It is important to note that lung cancer tumors were excluded if there was ambiguity with respect to being primary or metastatic disease.

Recent research suggests that the Bayesian paradigm should be used for modeling biases such as those due to misclassification/measurement error, missing data, selection bias, and unmeasured confounding. Greenland [9–11] provides an excellent overview of Bayesian methods in epidemiology, including the important case of modeling bias. The Bayesian approach provides an operational way to combine both validation data and expert opinion to effectively account for biases due to issues such as misclassification and missing data.

In the misclassification/measurement error literature, the different components of the full model are often referred to as the outcome model, exposure model, and measurement model, see [12] for a detailed discussion. For the lung cancer outcome, we assumed a logistic regression model for the outcome model:

| (1) |

where y1 represented the presence (y1 = 1) or absence (y1 = 0) of primary lung cancer, x1 represented the presence (x1 = 1) or absence of radiotherapy (x1 = 0) and x2 represented the presence (x2 = 1) or absence of smoking (x2= 0). These were the two risk factors of interest. The confounder is x3 representing breast carcinoma histology (BCH), where x3 = 1 if adenocarcinoma and 0 otherwise. An interaction term was included in the model given that the interaction of radiotherapy and smoking was of interest. We are using a prospective logistic regression model, which as discussed in [12] can be used for large sample sizes. For instance, in a simulated example in [12] with 500 cases and 500 controls there was only a slight difference in posterior means for the prospective and retrospective analysis while for only 100 cases and 100 controls there was a moderate but not major difference. Our total sample size of 580 should be large enough so that there are no major differences between the prospective and retrospective analyses.

The next component we consider is the exposure model [12]. Since there are two misclassified variables, radiotherapy and smoking, the exposure model is particularly important. Here we assumed the following conditional densities:

where

and

The order of conditioning (smoking conditioned on radiotherapy and BCH, radiotherapy only conditioned on BCH) was arbitrary. We provide additional justifications for our choice when we describe how we further allow for missing data.

The last component of the model for misclassification is the measurement model for the surrogates for radiotherapy and smoking. That is, x1 and x2 are not observed, but instead, fallible values are recorded. These surrogates were given as:

and

where Srad was the sensitivity of the method for determining radiotherapy status, Crad was the specificity, while Ssmk and Csmk were similarly defined for smoking status. Thus, in this analysis we assumed non-differential misclassification, i.e. that the misclassification parameters did not depend on the outcome or on any of the covariates. Dealing with a similar situation, MacLehose et al. (2009) accounted for misclassification of smoking when evaluating if smoking during pregnancy impacted the probability of developing an orofacial cleft [5]. In their most general model they allowed for a different sensitivity and specificity for subjects with and without orofacial cleft. For our data, we had no a priori reason to believe the sensitivities and specificities varied with respect to the outcome, but our approach could be easily extended to accommodate such variability if expert opinion or external data are available to allow the estimation of these parameters.

We had moderate amounts of missing data for smoking and breast carcinoma histology; radiotherapy also had few missing values. Specifically, there were 73 missing values for breast carcinoma histology, 66 missing values for smoking, and only 6 missing values for radiotherapy. To account for the missing data, we assumed a missing at random (MAR) missing data mechanism. Since we already modeled radiotherapy and smoking to account for their misclassification, we only needed to add a logistic regression model component for BCH. Since there are no other covariates involved, this yields the simple model

For situations where there are other covariates, they would be included in the usual way. Note that we have expressed the full joint distribution for all variables (y, x1, x2, x3) as a product of conditional distributions. While the order may seem arbitrary, our reasoning is as follows. We have the least direct information about smoking, because not only it is potentially misclassified but there are also 66 missing observations, so it is reasonable to model smoking conditional on radiotherapy and BCH, since BCH is not misclassified and radiotherapy only has 6 missing observations. A similar argument is why we chose to leave BCH for last, as it does have missing values and it is not considered to be misclassified. We looked at alternative ways to express the joint distribution and the resulting inferences were almost identical, so there does not appear to be sensitivity to the choice of the order of conditioning.

Priors/Validation data

We assumed that a combination of informative priors along with external validation data were available to allow us to perform inference regarding our parameters of interest, i.e. the parameters corresponding the joint effects of radiotherapy and smoking. Modeling of misclassification leads to more parameters than can be estimated by the data alone. For the logistic regression parameters from the outcome model (1) and from the measurement model we assumed that limited prior information was available, and so we used relatively non-informative priors, i.e. priors with very little influence. Specifically, these priors are:

that is, normal distributions with mean 0 and variance 4 (standard deviation = 2). These priors convey the information that all the odds ratios are likely to be between 0.02 and 50. The results of [1, 2, 4] are all well within these ranges justifying these priors as non-informative. These priors are also non-informative for the intercepts as well.

We assumed beta priors for the sensitivities and specificities for the assessment of radiotherapy and smoking status. The beta distribution is often used [13] for at least three reasons. One, the values allowed by the beta distribution are in the unit interval, (0, 1), which matches the range for the sensitivities and specificities. Secondly, the beta distribution is the conjugate prior for binomial data. So, if validation data exists, combining the prior and validation data yields a beta distribution that can be used as the prior for the current data. Finally, the beta distribution is flexible and allows a range of shapes. We denote our beta priors as

For the smoking status, available as self-reported from the medical records, validation data were available to help parameterize the prior distributions. For illustration we used results from [14] which are consistent with the validation data used by [5]. In a sample of 64 smokers, 59 claimed smoking on self-report while 5 incorrectly claimed to not be smokers. In the same study, in a sample of 232 non-smokers, 227 claimed non-smoking status on self-report while 5 incorrectly claimed to be smokers. Combining these external validation data with any prior information that was available resulted in:

Since validation data were available, it was unnecessary to utilize any additional expert information and we set aSsmk = bSsmk = aCsmk = bCsmk = 1. These diffuse beta(1, 1) priors combined with the validation data yielded:

In order to determine the form of the priors for the sensitivity and specificity of radiotherapy, we combined the values from an expert and the values used in the sensitivity analysis from [7]. Specifically, Schootman et al. [8] determined that for radiotherapy data from medical records both the sensitivity and specificity had modes of 0.9, and that there was more confidence in the sensitivity estimate than in the specificity estimate. We used the following priors for these parameters:

To illustrate how priors for the sensitivity and specificity can be elicited we used BetaBuster (http://www.epi.ucdavis.edu/diagnostictests/betabuster.html). BetaBuster is a useful tool for eliciting expert opinion for probabilities. It requires an elicited mode (most likely) value and a percentile. With this information a unique beta distribution is provided. For instance, suppose the expert believes the mode to be 0.9 with a 5th percentile of 0.82. This yielded approximately a beta(60.5, 7.6), which is the prior we used for the sensitivity. Note that this prior is approximately equivalent to an experiment where out of 68 patients who received radiotherapy, 60 were correctly classified. Similarly, the information for the specificity is approximately equivalent to 48 patients with 43 correctly classified.

It should be noted that we are making strong assumptions by transporting the information from these previous studies into our current work. However, our main goal is to perform a sensitivity analysis to see the impact of potential misclassification on the results. Three of the four priors we are using are not overly informative for a sensitivity type analysis. For instance, the 95% equal tail interval for the prior for Crad is (0.781, 0.957). Thus our analysis ends up being a sensitivity analysis in the spirit of [15]. In our results section we downweight the priors by one half to investigate the impact of the informativeness of the priors.

Model fitting

For comparative purposes we considered the “full model”, that allowed for both misclassification of the main risk factors and missing data, an alternative model that only accounted for misclassification, another alternative model that only accounted for missing data, and the naïve model that ignored both sources of bias. When the missing data was ignored, only observations where all records are available (complete cases) were used, so the sample size reduced from 580 to 443. We fit all models using the free software package WinBUGS v 14. Each model fit was based on 520,000 iterations. The first 20,000 iterations were discarded as a burn-in and the remainder were “thinned”, retaining every 25th for inference, leaving 20,000 iterations. History, autocorrelation, and density plots were used to assess convergence of the sampler. The WinBUGS code is provided in the Appendix.

Accounting for misclassification, measurement error, and other sources of bias can lead to convergence problems and remedial measures are often required. Thinning the chains to reduce autocorrelation and improve convergence. For instance, response misclassification is accounted for in [16] and to obtain convergence the chain is required to be thinned using every 100th iteration for inference. In a study on diagnostic tests with no gold standard in [17], for some data sets, thinning of 250 was required to obtain convergence. Thus thinning of 25 would not be considered extraordinary in models such as the ones considered here.

Results

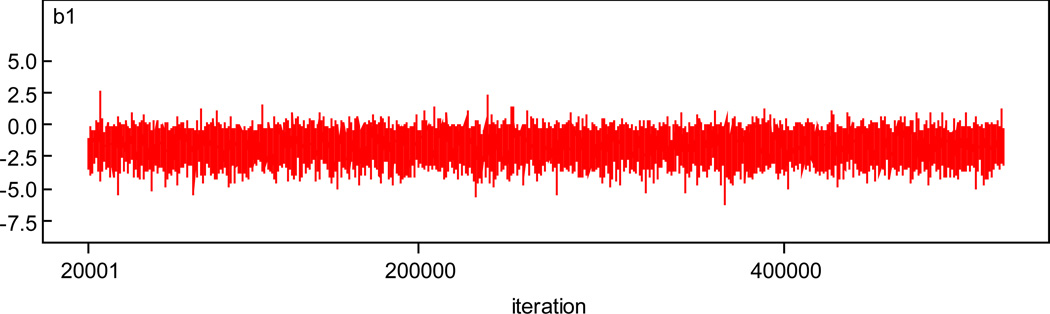

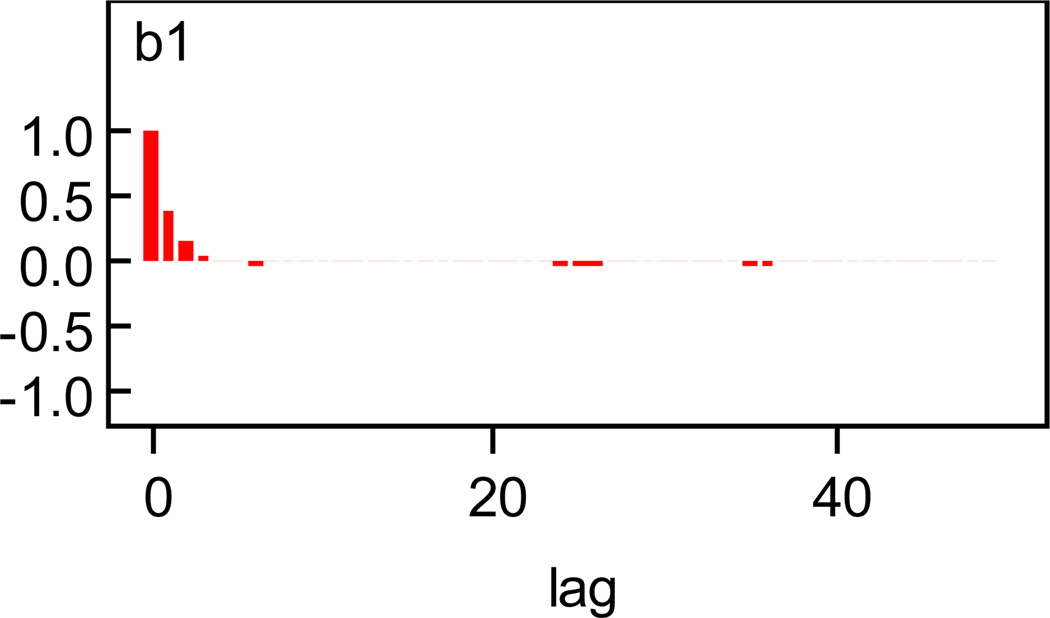

We first illustrate the convergence of the chains. History and autocorrelation plots for β1 for the full model, where misclassification and missing data are accounted for, are given in Figures 1 and 2. Plots for other parameters are given in the appendix. There is little evidence against convergence.

Figure 1.

History Plot for β1.

Figure 2.

Autocorrelation Plot for β1.

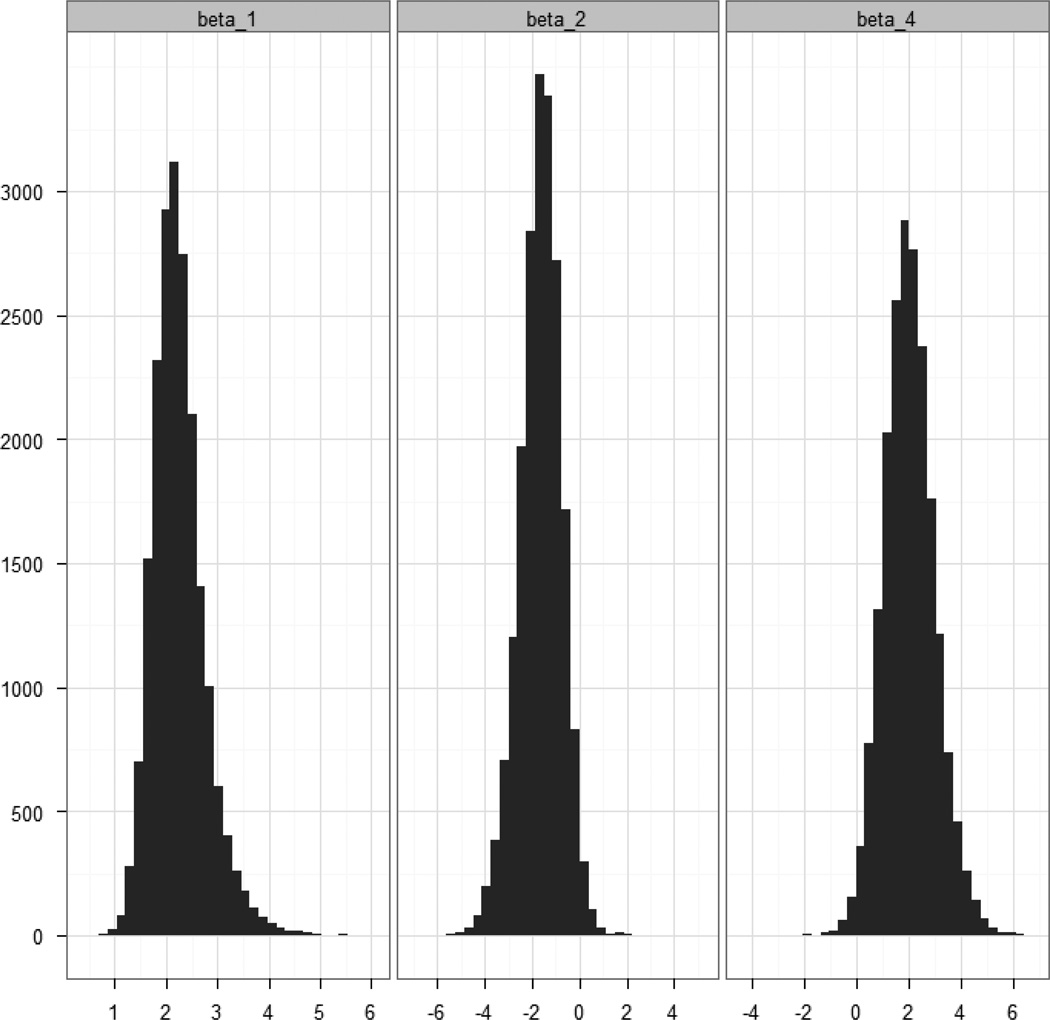

The posterior summaries of the odds ratios for the four models are provided in Table 1. Because of the skewed nature of the posterior distributions for the odds ratios of interest we used posterior medians as point estimates and we reported corresponding 95% credible intervals. The posteriors for the logistic regression parameters for radiotherapy, smoking, and the interaction are presented graphically in Figure 3. We note that the results from the naïve model were consistent with those from [3] in that radiotherapy was not statistically significant (among those not exposed to smoking), smoking was significant (among those not exposed to radiotherapy), and the combination of radiotherapy and smoking was significant (compared with those not exposed to smoking or radiotherapy), where we determined “significance” as whether the 95% credible intervals contained 1 or not.

Table 1.

Odds Ratios and 95% Credible Intervals for the Joint Associations of Radiotherapy and Smoking with Primary Lung Cancer among Breast Cancer Survivors.

| Naïve | Accounting for Missing Data |

Accounting for Misclassification |

Accounting for Misclassification and Missing Data |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiotherapy | Smoking | Cases Controls |

||||||

| No | No | 29 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 87 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Yes | No | 12 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.27 | 0.21 | ||

| 67 | (0.28, 1.25) | (0.23, 0.96) | (0.04, 1.34) | (0.03, 0.92) | ||||

| No | Yes | 118 | 5.28 | 6.03 | 7.46 | 8.89 | ||

| 59 | (3.08, 9.28) | (3.63, 10.22) | (3.40, 24.00) | (4.10, 30.44) | ||||

| Yes | Yes | 102 | 7.91 | 8.05 | 13.00 | 13.22 | ||

| 34 | (4.40, 14.60) | (4.66, 14.27) | (5.54, 49.20) | (5.76, 48.37) | ||||

Figure 3.

Posterior Distributions for β1, β2, and β4.

Accounting for the misclassification had two major effects. The first was that all the point estimates were shifted away from the null hypothesis of no effect. This was not surprising as it is well known that in general ignoring non-differential misclassification causes point estimates to be biased towards the null. The second impact was in the variability. The 95% credible intervals were considerably wider for the two models that accounted for misclassification (the “full model” and the model that accounted only for misclassification) than for the two models that ignored the misclassification (the model that accounted only for missing data and the naïve model). Accounting for missing data had less impact for our data. The results from the two models that accounted for missing data under the MAR assumption (the “full model” and the model that accounted only for missing data) were in general consistent with those from the two models that did not account for missing data (the model that only accounted for misclassification and the naïve model) with the only exception that the 95% credible interval for radiotherapy from the model that accounted only for missing data did not include 1. There was a general tendency for the odds ratio estimates of interest to move away from 1 while going from the naïve model to the “full model”. Overall the results of the four models were consistent with the pattern of associations from [3], while suggesting the presence of stronger joint associations of radiotherapy and smoking with primary lung cancer among breast cancer survivors, than those found in the original paper [3].

Though they are not the primary parameters of interest, we also report in Table 2 the posteriors for the misclassification parameters for the model that accounts only for misclassification, and also for the model that accounts for both missing data and misclassification. We also include summaries of the prior distributions as well. The posterior distributions for the parameters from these two models are very similar and there is very little updating from the prior distribution. In fact, the 95% credible intervals for Crad are actually slightly wider than the prior interval. This is not unusual, in that there is very little information in the data and in the example considered in [15], the posterior distribution for the false positive rate, i.e. 1 – specificity, is slightly wider than the prior interval.

Table 2.

Posterior Medians and 95% Credible Intervals for Sensitivities and Specificities.

| Prior | Accounting for Misclassification |

Accounting for Misclassification and Missing Data |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Ssmk | 0.913 | 0.917 | 0.922 |

| (0.830, 0.965) | (0.853, 0.965) | (0.864, 0.966) | |

| Csmk | 0.975 | 0.975 | 0.975 |

| (0.949, 0.990) | (0.950, 0.991) | (0.950, 0.990) | |

| Srad | 0.892 | 0.884 | 0.884 |

| (0.804, 0.951) | (0.790, 0.947) | (0.788, 0.948) | |

| Crad | 0.889 | 0.875 | 0.866 |

| (0.781, 0.957) | (0.747, 0.950) | (0.757, 0.953) | |

As mentioned in the methods section, an important question is how applicable is the prior information we used to our current study. The priors allow a fairly wide range of values for all the parameters except Csmk which does have a particularly tight prior. We down-weighted all prior parameters by one half and reran the analysis to see the impact on the results. So, for instance, for Ssmk the prior was a beta(30, 3) instead of a beta(60, 6). In Table 3 we provide the posterior summaries of the regression parameters from the outcome model when accounting for misclassification and missing data for the original model and when down-weighted. As it can be seen, the point estimates for both models are very similar. The posterior variability, as illustrated by the credible intervals being slightly wider for the model with less prior information. This has a material effect for the radiotherapy coefficient as the wider interval includes 0. However, overall, the model still converges and the similarity of the results shows there is robustness to choice of the prior distributions.

Table 3.

Posterior Medians and 95% Credible intervals for Regression Parameters under Two Different Prior Distributions.

| Original prior | Prior information divided by 2 |

|

|---|---|---|

| β1 | −1.59 | −1.52 |

| (−3.57, −0.03) | (−3.48, 0.07) | |

| β2 | 2.20 | 2.14 |

| (1.42, 3.47) | (1.31, 3.44) | |

| β3 | 0.85 | 0.84 |

| (0.25, 1.51) | (0.24, 1.50) | |

| β4 | 2.02 | 1.97 |

| (0.26, 4.10) | (0.24, 4.09) | |

Discussion

Despite the fact that misclassification and missing data are important sources of bias affecting many epidemiological studies, the vast majority of studies only acknowledge their presence as potential limitations without attempting to formally adjust for them. To help remediate this situation, we provided a detailed description and an example of the code to implement a sensitivity analysis approach to evaluate the bias due to misclassification and missing data. Although we focused on the evaluation of the joint associations of radiotherapy and smoking with primary lung cancer for breast cancer survivors using the data from [3], our approach can be easily modified to deal with other situations where misclassification and/or missing data arise. We did not consider the presence of outcome misclassification, given that lung cancer tumors were excluded from our data if there was ambiguity with respect to being primary or metastatic disease. Our methods can be easily extended to deal with outcome misclassification by using the results regarding the pathological confirmation of primary lung cancer following breast cancer from [15]. Another important source of bias is unmeasured confounding. Both Garshick et al. [18] and Richardson [19] discuss the impact of an unmeasured confounder on inferences about lung cancer risk. While for this study we did not consider the presence of unmeasured confounding, our approach could easily be extended to account for issues such as unmeasured confounding and selection bias. See for example [20, 21].

Previous researchers have stressed the importance of accounting for bias in epidemiological studies [5, 12, 14]. We echo their comments and hope researchers will include carefully planned sensitivity analyses given the frequent presence of potential biases. Once biases are properly accounted for, risk factors that were thought to be trivial could be found to be important and motivate further studies where these biases could be better controlled for.

Potential limitations of our work are the applicability of the validation data/informative priors and the assumption of non-differential misclassification. The fact that our results only changed mildly when reducing the informativeness of the priors gives us some assurance of robustness, but if the misclassification rates are significantly different from what we have assumed here, our results may not apply. In terms of differential versus non-differential misclassification, it would be straight forward to adapt our WinBUGS code to the differential misclassification case, but that would lead to four more parameters that would need informative priors via either validation data or prior elicitation. Another limitation of our analysis and that of [3] is ignoring breast cancer stage. This was excluded from [3] due to the high missingness and we wanted our analysis to mirror that of [3] closely, so we omitted it as well.

There are several possible extensions to the work we have done here. We assume validation data is only available from a single source. If multiple sources of validation data are available, the hierarchical model applied in [22] for the case of a single misclassified covariate could be extended by allowing for multiple misclassified covariates as in our models. We assumed the sensitivities and specificities were independent, while the model in [22] allows for correlation. Another area for future work would be a thorough simulation study to investigate the amount of validation data/prior information required for the model to perform well in terms of bias and interval coverage and also test robustness to assumptions such as using a prospective logistic regression model for case-control data.

We employed Bayesian methods because they provide a flexible framework to combine both external validation data and expert opinion to account for misclassification of radiotherapy and smoking. As part of our sensitivity analysis we compared the results of four models of interest: a “full model” that addressed both misclassification and missing data, a model that corrected only for misclassification, another model that accounted only for missing data, and the naïve model that ignored both sources of bias. There were noticeable differences between the results of the four models with respect to the posterior distributions of the parameters of interests, although the observed differences were in the expected direction given the specifics of the sensitivity analysis performed. Despite those differences we found that the overall conclusions regarding the pattern of associations of the two risk factors of interest with primary lung cancer were the same regardless of the model used. Based on our limited sensitivity analysis we strongly recommend the use of Bayesian methods as the ones described in this paper to perform sensitivity analyses for assessing the robustness of study findings with regard to the potential effect of important sources of bias, such as misclassification and missing data.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Appendix:

Contributor Information

George Luta, Department of Biostatistics, Bioinformatics, and Biomathematics, Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Georgetown University, Building D, Suite 180, 4000 Reservoir Road, NW, Washington DC, 20057-1484, Tel: (202) 687-8203, Fax: (202) 687-2581, gl77@georgetown.edu

Melissa Belle Ford, MBFord Consulting, 2422 Marika Circle, Wichita Falls, TX 76308, 940-696-8058 (h), 940-782-1407 (c), mbford-hou@att.net.

Melissa Bondy, Associate Director for Cancer Prevention and Population Sciences, Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center, Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Dan L. Duncan Endowed Professor and McNair Scholar, Baylor College of Medicine, One Baylor Plaza, Mail Stop BCM305, Houston, Texas 77030-3498, 713-798-2953 (office), 713-927-6639 (cell), mbondy@bcm.edu

Peter G. Shields, Deputy Director, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Professor, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University Medical Center, 300 W. 10th Avenue, Suite 519, Columbus, OH 43210-1280, Phone: 614-688-6563, peter.shields@osumc.edu

James D. Stamey, Department of Statistical Science, Baylor University, One Bear Place #97140, Waco, TX, 76798, Tel: (254) 710-7405, james_stamey@baylor.edu

References

- 1.Prochazka M, Granath F, Ekbom A, Shields PG, Hall P. Lung cancer risks in women with previous breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(11):1520–1525. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prochazka M, Hall P, Gagliardi G, Granath F, Nilsson BN, Shields PG, et al. Ionizing radiation and tobacco use increases the risk of a subsequent lung carcinoma in women with breast cancer: case-only design. Clin Oncol. 2005;23(30):7467–7474. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.7335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford MB, Sigurdson AJ, Petrulis ES, Ng CS, Kemp B, Cooksley C, et al. Effects of smoking and radiotherapy on lung carcinoma in breast carcinoma survivors. Cancer. 2003;98(7):1457–1464. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufman EL, Jacobson JS, Hershman DL, Desai M, Neugut AI. Effect of breast cancer radiotherapy and cigarette smoking on risk of second primary lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(3):392–398. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacLehose RF, Olshan AF, Herring AH, Honein MA, Shaw GM, Romitti PA. Bayesian methods for correcting misclassification: an example from birth defects epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2009;20(1):27–35. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818ab3b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S. The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(7):1086–1093. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schootman M, Jeffe DB, Gillanders WE, Yan Y, Aft R. The effects of radiotherapy for the treatment of contralateral breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;103(1):77–83. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9354-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubin DB. Inference and missing data (with discussion) Biometrika. 1976;63:581–592. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenland S. Bayesian perspectives for epidemiological research: I. Foundations and basic methods. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(3):765–775. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenland S. Bayesian perspectives for epidemiological research. II. Regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(1):195–202. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenland S. Bayesian perspectives for epidemiologic research: III. Bias analysis via missing-data methods. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(6):1662–1673. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gustafson P. Measurement Error and Misclassification in Statistics and Epidemiology: Impacts and Bayesian Adjustments. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gustafson P, Nhu DL, Saskin R. Case-control analysis with partial knowledge of exposure misclassification probabilities. Biometrics. 2001;57:598–609. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Knight GJ. Use of serum cotinine to assess the accuracy of self reported non-smoking. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293(6557):1306. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6557.1306-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox MP, Lash TL, Greenland S. A method to automate probabilistic sensitivity analyses of misclassified binary variables. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;34:1370–1376. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tennis M, Singh B, Hjerpe A, Prochazka M, Czene K, Hall P, et al. Pathological confirmation of primary lung cancer following breast cancer. Lung Cancer. 2010;69(1):40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paulino CD, Silva G, Achcar JA. Bayesian analysis of correlated misclassified data. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis. 2005;49:1120–1131. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toft N, Innocent GT, Gettinby G, Reid SWJ. Assessing the convergence of Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods: An example from evaluation of diagnostic tests in absence of a gold standard. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2007;79:244–256. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garshick E, Laden F, Hart JE, Smith TJ, Rosner B. Smoking imputation and lung cancer in railroad workers exposed to diesel exhaust. Am J Ind Med. 2006;49(9):709–718. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCandless LC, Gustafson P, Levy AR, Richardson S. Hierarchical priors for bias parameters in Bayesian sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounding. Stat Med. 2012;31:383–396. doi: 10.1002/sim.4453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCandless LC, Gustafson P, Levy AR. A sensitivity analysis using information about measured confounders yielded improved uncertainty assessments for unmeasured confounding. J Clin Epi. 2008;61:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu H, Wang Z, Cole SR, Greenland S. Sensitivity analysis of misclassification: A graphical and a Bayesian approach. Annals of Epidemiology. 2006;16:834–841. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.