Abstract

In the present study, toxicity of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) was investigated in the nematode, Caenohabditis elegans focusing on the upstream signaling pathway responsible for regulating oxidative stress, such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades. Formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was observed in AgNPs exposed C.elegans, suggesting oxidative stress as an important mechanism in the toxicity of AgNPs towards C. elegans. Expression of genes in MAPK signaling pathways increased by AgNPs exposure in less than 2-fold compared to the control in wildtype C.elegans, however, those were increased dramatically in sod-3 (gk235) mutant after 48 h exposure of AgNPs (i.e. 4-fold for jnk-1 and mpk-2; 6-fold for nsy-1, sek-1, and pmk-1, and 10-fold for jkk-1). These results on the expression of oxidative stress response genes suggest that sod-3 gene expression appears to be dependent on p38 MAPK activation. The high expressions of the pmk-1 gene 48 h exposure to AgNPs in the sod-3 (gk235) mutant can also be interpreted as compensatory mechanisms in the absence of important stress response genes. Overall results suggest that MAPK-based integrated stress signaling network seems to be involved in defense to AgNPs exposure in C.elegans.

Keywords: Caenorhabditis elegans, Silver nanoparticles, Mitogen activated protein kinase, Oxidative stress

INTRODUCTION

Due to the wide application of nanoparticles (NPs) in various fields, research on their toxicity has grown exponentially over the past few years (Campbell and Compton, 2010; Kahru and Dubourguier, 2010). Nevertheless, serious deficiencies still exist in the knowledge relating to this area, especially in nanoecotoxicology. Some of the studies previously conducted on NP toxicity have also reported oxidative stress as one of the most important toxicity mechanisms related to NP exposure (Limbach et al., 2007; Monteiller et al., 2007).

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are used in increasing numbers of products, and given the potentially high toxicity and specific concerns associated with the use of AgNPs, particular attention to their toxicity may be warranted. Recent literatures on the toxicity and risk of AgNPs suggest that, directly or indirectly, oxidative stress may be a potential toxic mechanism, as AgNPs exposure can trigger oxidative stress or exacerbate pre-existing oxidant reactions; thereby, inducing toxicity (Roh et al., 2009; Limbach et al., 2007).

However, even though numerous recent studies have suggested AgNPs may exert their toxicity via oxidative stress, the upstream signaling mechanism responsible for regulating the oxidative stress by AgNPs is still poorly understood, especially in non-mammalian models, such as Caenorhabditis elegans. The nematode C. elegans is an excellent model organism for research on and assessment of environmental contaminants, particularly, for the study of the toxicological relevance of chemical-induced molecular-level responses, as the comprehensive knowledge of the genome of C. elegans and functional genomics tools allow for a clearer insight into the operation of toxic mechanisms initiated by chemicals acting upon organisms, mechanisms that can have adverse effects at the organism level.

Our previous study on the ecotoxicity of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) in the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans, suggested that oxidative stress may be an important mechanism in the toxicity of AgNPs, and PMK-1 p38 MAPK is involved in it (Roh et al., 2009; Lim et al., 2012).

In the present study, as a continuation of our previous work, the involvement of oxidative stress as a toxic mechanism of AgNPs was investigated, focusing on mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways. MAPK, extracellular signal-regulating kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 MAPK serve as transducers of extracellular stimuli, which allow cellular adaptation to environmental changes, and play key roles in many diverse physiological processes, including stress responses (Kyriakis and Avruch, 2001; Kim et al., 2009). Although, the roles of the p38 MAPK and JNK pathways in various stress responses of C. elegans have already been reported (Troemel et al., 2006; Back et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2002), they have not been approached in an toxicological context. In the present study, to test whether oxidative stress was directly involved in AgNPs toxicity reactive oxygen species (ROS) was measured in AgNPs exposed C. elegans and subsequently, the downstream genes, known to be regulated by the MAPK signaling pathway, were also investigated in wildtype and mutant C. elegans exposed to AgNPs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Maintain of C. elegans and treatment of AgNPs to C. elegans. C. elegans were grown in Petri dishes on nematode growth medium (NGM) and fed with OP50 strain Escherichia coli, according to a standard protocol (Brenner, 1974). Worms were incubated at 20℃, with young adults (3 days old) from an age-synchronized culture then used in all the experiments. Detailed information on the mutant strains used in this study is presented in Supporting Table 1. Wildtype and mutants were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (www.CGC.org) at the University of Minnesota. For treatment to C.elegans, AgNPs were prepared and characterized as described previously (Roh et al., 2009). The dispersion of AgNPs was controlled by sonicating for 13 h (Branson-5210 sonicator, Branson Inc., Danbury, CT, USA), stirring for 7 days, and filtering through a cellulose membrane (pore size 100 nm, Advantec, Toyo Toshi Kaisha, Japan; Eom and Choi, 2009; Bae et al., 2010). The size distribution of the AgNPs was examined by Energy filtering transmission electron microscopy (LIBRA 120 TEM, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany) and Photal dynamic light scattering (DLS-7000, Otsuka Electronics Co., Inc., Osaka, Japan). From these results, the range of the main size of the NPs distributed in the medium was about 30~50 nm (data not shown), even though AgNPs tended to agglomerate during the experiment. From stock solutions, experimental concentrations (0.1, and 1 mg/l) of AgNPs were prepared in k-media (0.032 M KCl and 0.051 M NaCl; Williams and Dusenbery, 1990).

ROS formation. To detect the levels of ROS, wildtype and mutants were exposed to 1 mg/l of AgNPs for different time intervals, then transferred to 0.5 ml of S buffer, containing 15 μM 2, 7-dichlorofluoroscein diacetate (DCFHDA, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and then pre-incubated for 30 min at room temperature. To confirm the role of ROS, worms were pre-treated with a strong antioxidant, Nacetylcysteine (NAC), in the presence of AgNPs. ROS formation was reduced by pre-treatment with 300 μM NAC for 2 h before AgNPs exposure. The fluorescence was observed using a Leica DM IL microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), with images obtained using a Leica DCF 420C camera (Leica). Levamisole (2 mM, Sigma-Aldrich) was applied to C. elegans, with pictures of the live worms then taken.

Quantitative real-time PCR. For the quantitative real time-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis, wildtype and mutants were exposed to 1 mg/l of AgNPs at different time intervals (from 4 to 48 h) and then analyzed using the IQTM SYBR Green SuperMix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). PCR was carried out on 12 selected genes, using a Chromo4 Real- Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). The primers were constructed based on sequences retrieved from the C. elegans database (www.wormbase.org, Supporting Table 2), the qRT-PCR conditions optimized, and efficiency and sensitivity tests performed for each gene prior to the main experiment. Three replicates were conducted for each qRT-PCR analysis.

Statistical analysis. Data are presented in arbitrary units compared to the control, with statistical differences between the wildtype and mutants relating to survival and reproduction determined by an analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, with a Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. All statistical tests were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences 12.0 KO (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

AgNPs characterization. As the physicochemical attributes of NPs are critical parameters in determining their degree of toxicity, prior to the toxicity experiments, the characterization of AgNPs were investigated, as described previously (Roh et al., 2009). Particle characterization using TEM and DLS confirmed that the sizes of particles applied in the toxicity test were mainly within the range 20~ 30 nm and evenly distributed in the test medium, as described previously (Lim et al., 2012).

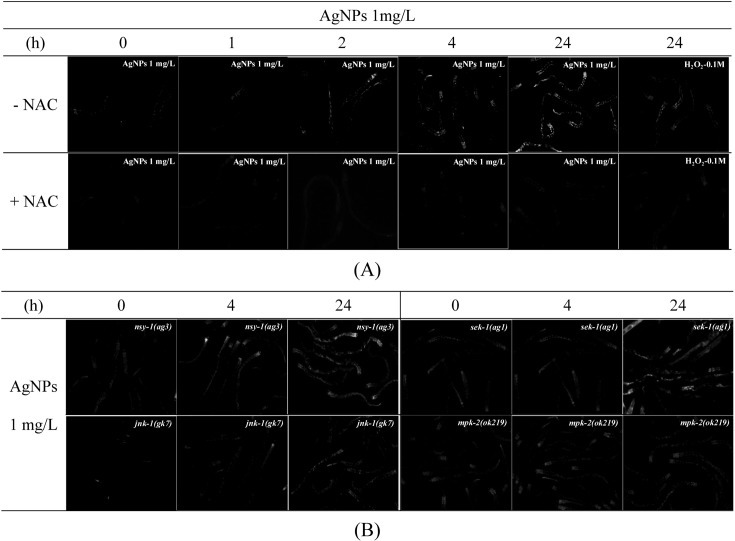

Formation of ROS by AgNPs exposure. Recent studies (AshaRani et al., 2009; Kawata et al., 2009), including our previous one (Roh et al., 2009), indicated that oxidative stress is a potential toxic mechanism of AgNPs. In our previous study, we investigated ROS formation, as direct evidence of oxidative stress, in AgNPs exposed wildtype as well as, pmk-1(km25) mutant (Lim et al., 2012). Increased ROS formation induced by AgNPs in wildtype (N2) C. elegans was rescued in the pmk-1 (km25) mutant, which suggests oxidative stress is an important mechanism of toxicity of AgNP and the PMK-1 p38 MAPK plays an important role in AgNPs toxicity(Lim et al., 2012). In this study, to investigate involvement of other MAPK genes in AgNPs induced oxidative stress, ROS formation was measured in four MAPK mutants strain, such as, nsy-1(ag3), sek-1(ag1), jnk-1(gk7), mpk-2(ok219) (Fig. 1). Increases in ROS formation were observed 1, 2, 4 and 24 h after AgNPs exposure in wildtype C. elegans. The fluorescence intensity was more significant after 24 h exposure than during early exposure times. Increased fluorescence on AgNPs exposure was suppressed by pretreatment with NAC, an important antioxidant, which serves as a precursor for the synthesis of glutathione (Fig. 1A). This confirms that the AgNP-induced increase in ROS formation was due to oxidative stress. Subsequently, the degree of ROS formation was compared across the mutant strains 4 and 24 h after exposure to 1 mg/l of AgNPs (Fig. 1B). The responses of nsy-1(ag3), sek- 1(ag1) and mpk-2(ok219) to AgNPs exposure were similar to that of the wildtype. Slight decreased of ROS formation was observed in jnk-1(gk7) mutant.

Fig. 1. The formation of ROS on exposure to AgNPs. The formation of ROS was observed in wildtype (A) and mutants (nsy-1(ag3), sek- 1(ag1), jnk-1(gk7), mpk-2(ok219), (B). The worms were incubated with 15 μM of DCFH-DA at 37℃ for 30 min, and then observed under fluorescence microscopy. To detect the level of ROS, the wildtype was exposed to 1mg/l of AgNPs for 0, 1, 2, 4 and 24 h. 100 μM H2O2 was used as the positive control, with the antioxidant NAC pre-treated to confirm that the formation of ROS was the result of oxidative stress. The mutants were exposed to 1mg/l AgNPs for 4 and 24 h. These pictures were taken under the 100 times magnification of the actual size.

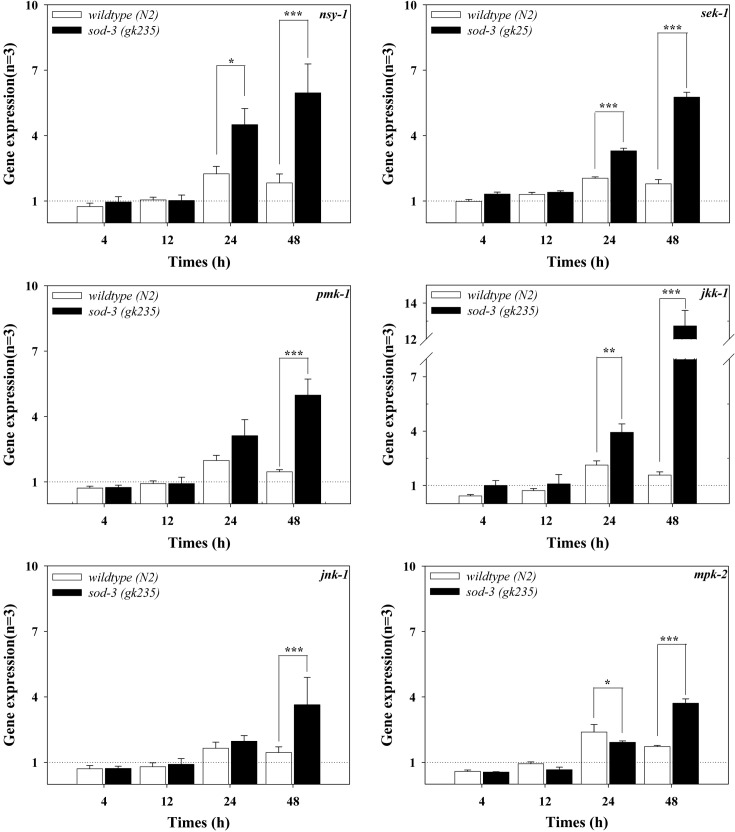

Expression of genes in MAPK signaling pathway by AgNPs exposure. In our previous study, we reported that PMK-1 p38 MAPK was involved in AgNPs-induced oxidative stress (Lim et al., 2012). In this study, we investigated involvement of C. elegans MAPK signaling pathways in response to AgNP exposure. The response of P38 MAPK signaling pathway, (i.e. nsy-1 (MAPK kinase kinase, MAPKKK)/ sek-1 (MAPK kinase and MAPKK)/pmk-1 (p38 MAPK)), JNK MAPK pathways, (i.e. jkk-1 (MAPKK) and jnk-1 (JNK MAPK)) and ERK MAPK pathway (i.e. mpk-2 (ERK MAPK)), were investigated in AgNPs exposed C. elegans. To gain an insight of the role of MAPK pathways in oxidative stress, the response was also investigated also in sod-3(gk235) mutant (Fig. 2). In the wildtype exposed to AgNPs, the observed alterations in all the MAPK genes were less than 2 fold compared to the control; however, the expressions were highest after 24 h of exposure in all tested MAPK genes.

Fig. 2. Expressions of the genes in the MAPK signaling pathways in wildtype and sod-3(gk235) mutant. C. elegans was exposed to 1mg/l of AgNPs for 0, 4, 12, 24 and 48 h, with qRT-PCR performed for the analysis of gene expressions. The results are expressed in relative units compared to the beginning of the experiment (0 h = 1). Statistically significant differences were analyzed between the response of the wildtype and mutants using a one-way ANOVA (number = 3; mean ± standard error of mean, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

The pattern of MAPK mRNA expression in wildtype was different from those in sod-3(gk235) mutants (Fig. 2). A weak increase in MAPK mRNA was observed (mostly less than 2-folds compared to control) in the wildtype. In the sod-3(gk235) mutant, the degree of increased expression was as significant (about 2~6 fold compared to the control), except for the expression of jkk-1, where the increase reached about 10-fold that in the control after 48 h of exposure. In the sod-3(gk235) mutant, a dramatic increase in the expression of the gene of JNK MAPK, jkk-1, as well as significant increases in the genes in the p38 MAPK pathway, nsy-1, sek-1 and pmk-1 (Fig. 2), suggest the importance of the p38 and JNK signaling pathways in the oxidative stress condition induced due to the exposure of C. elegans to AgNPs.

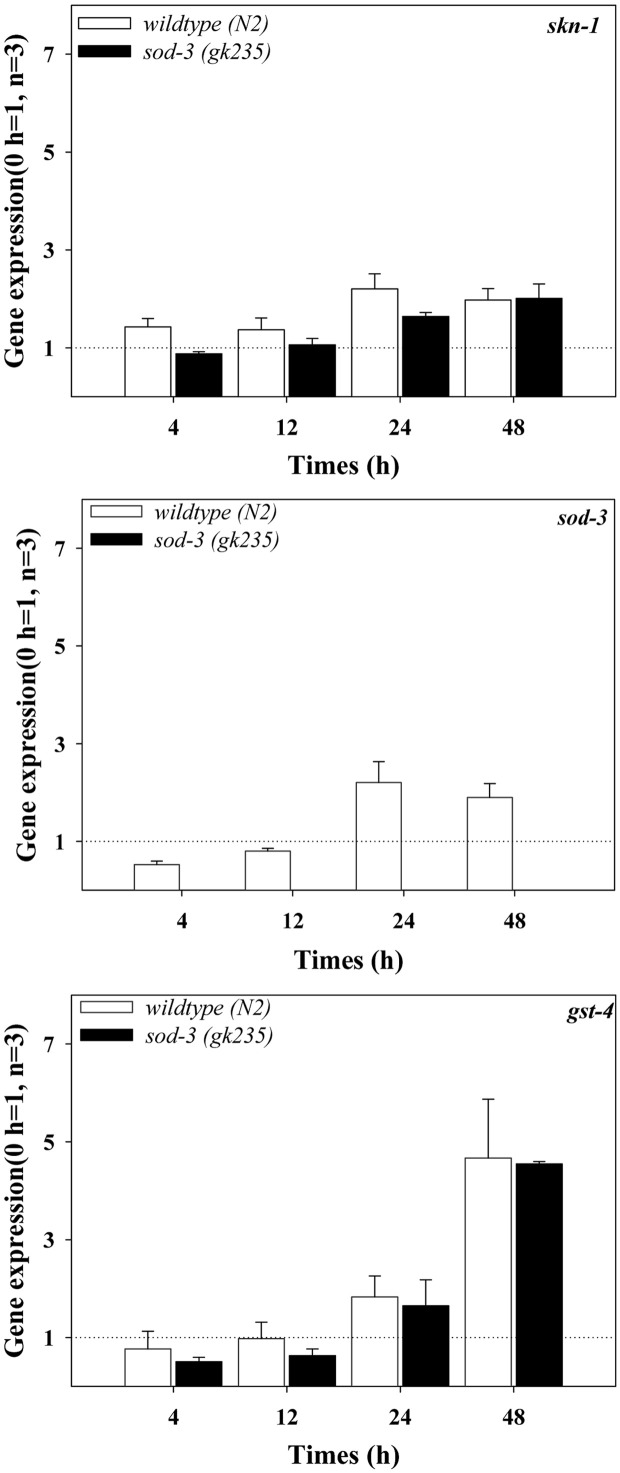

Oxidative stress response gene expression by AgNPs exposure. The expressions of oxidative stress responsive genes known to be regulated by the MAPK signaling pathway, such as skn-1, sod-3 and gst-4 were investigated in AgNPs exposed wildtype and sod-3(gk235) mutant at different exposure times (Fig. 3). Special attention was paid on the signaling cascade of pmk-1, skn-1 and gst-4, as activation of the p38-Nrf-2-GST signaling pathway upon oxidative stress has been identified in mammalian systems (Giudice and Montella, 2006). Inoue et al. (2005) reported that the C. elegans pmk-1, p38 MAPK pathway regulates the oxidative stress response via skn-1 on exposure to arsenate when used as a chemical stressor. An exposure time dependant increase in the expression of gst-4 genes was observed in wildtype exposed to AgNPs. And the skn-1 and gst-4 gene expression did not show any statistical difference in the wildtype or in sod-3(gk235) mutant (Fig. 3). These results suggest that skn-1 and gst-4 may not be involved in the expression of the AgNPs induced p38 mediated sod-3 gene. Further investigations on the discovery of a new transcription factor potentially involved in AgNPsinduced p38 and sod-3 activation, are warranted to fully elucidate the p38 MAPK mediated oxidative stress signaling in C. elegans on exposure to AgNPs. The high expressions of the pmk-1 gene 48 h exposure to AgNPs in the sod- 3(gk235) mutant can also be interpreted as compensatory mechanisms in the absence of important stress response genes.

Fig. 3. Expressions of gene known to be regulated by MAPK signaling pathway (skn-1, sod-3 and gst-4), in wildtype and sod- 3(gk235) mutant. C. elegans was exposed to 1mg/l of AgNPs for 0, 4, 12, 24 and 48 h, and qRT-PCR was performed for the analysis of gene expressions. The results are expressed in relative units compared to the beginning of the experiment (0 h = 1). Statistically significant differences were analyzed between the response of the wildtype and loss of function mutants using a one-way ANOVA (number = 3; mean ± standard error of mean, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

In conclusion, C. elegans seems to possess a MAPKbased integrated stress signaling network, as the MAPK activation pathway can be part of a general stress response, from infection to chemical stresses (Pei et al., 2008). The overall results of the present study on AgNPs may provide further evidence for this hypothesis. However, the mechanism by which these responses occurred merits further investigation. Especially, how C. elegans MAPK signaling pathways are involved in defense mechanisms on exposure to AgNPs would be an interesting research topic in the emerging field of nanotoxicity. C. elegans has been used as a non-mammalian in vivo model for human toxicity screening. Therefore, it is important to identify how the mechanism of toxicity of AgNPs observed in C. elegans study can be extrapolated to a mammalian system. However, there is still a serious lack of information on the toxicity of AgNPs for any general correlation between the findings from C. elegans and in vitro and in vivo mammalian studies. This challenging task, which is not limited to nanotoxicity testing, may be achieved via comparative toxicity studies using various biological systems.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2011-0003214).

References

- 1.AshaRani P.V., Low Kah Mun G., Hande M.P., Valiyaveettil S. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in human cells. ACS Nano. (2009);3:279–290. doi: 10.1021/nn800596w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Back P., Matthijssens F., Vlaeminck C., Braeckman B.P., Vanfleteren J.R. Effects of sod gene overexpression and deletion mutation on the expression profiles of reporter genes of major detoxification pathways in Caenorhabditis elegans. Exp. Gerontol. (2010);45:603–610. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bae E., Park H.J., Lee J., Kim Y., Yoon J., Park K., Choi K., Yi J. Bacterial Cytotoxicity of the Silver Nanoparticle Related to Physicochemical Metrics and Agglomeration Properties. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. (2010);29:2154–2160. doi: 10.1002/etc.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. (1974);77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell F.W., Compton R.G. The use of nanoparticles in electroanalysis: an updated review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. (2010);396:241–259. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-3063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eom H.J., Choi J. Oxidative stress of CeO2 nanoparticles via p38-Nrf-2 signaling pathway in human bronchial epithelial cell, Beas-2B. Toxicol. Lett. (2009);187:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giudice A., Montella M. Activation of the Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway: a promising strategy in cancer prevention. Bioessays. (2006);28:169–181. doi: 10.1002/bies.20359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoue H., Hisamoto N., An J.H., Oliveira R.P., Nishida E., Blackwell T.K., Matsumoto K. The C. elegans p38 MAPK pathway regulates nuclear localization of the transcription factor SKN-1 in oxidative stress response. Genes Dev. (2005);19:2278–2283. doi: 10.1101/gad.1324805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahru A., Dubourguier H.C. From ecotoxicology to nanoecotoxicology. Toxicology. (2010);269:105–119. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawata K., Osawa M., Okabe S. In vitro toxicity of silver nanoparticles at noncytotoxic doses to HepG2 human hepatoma cells. Environ. Sci. Technol. (2009);43:6046–6051. doi: 10.1021/es900754q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim D.H., Feinbaum R., Alloing G., Emerson F.E., Garsin D.A., Inoue H., Tanaka-Hino M., Hisamoto N., Matsumoto K., Tan M.W., Ausubel F.M. A conserved p38 MAP kinase pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity. Science. (2002);297:623–626. doi: 10.1126/science.1073759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim S., Choi J.E., Choi J., Chung K.H., Park K., Yi J., Ryu D.Y. Oxidative stress-dependent toxicity of silver nanoparticles in human hepatoma cells. Toxicol. In Vitro. (2009);23:1076–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kyriakis J.M., Avruch J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol. Rev. (2001);81:807–869. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim D., Roh J.Y., Eom H.J., Choi J.Y., Hyun J., Choi J. Oxidative stress related PMK-1 P38 MAPK activation as a mechanism of toxicity of silver nanoparticles on the reproduction of the nematode caenohabditis elegans. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. (2012);31:585–592. doi: 10.1002/etc.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limbach L.K., Wick P., Manser P., Grass R.N., Bruinink A., Stark W.J. Exposure of engineered nanoparticles to human lung epithelial cells: influence of chemical composition and catalytic activity on oxidative stress. Environ. Sci. Technol. (2007);41:4158–4163. doi: 10.1021/es062629t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monteiller C., Tran L., MacNee W., Faux S., Jones A., Miller B., Donaldson K. The pro-inflammatory effects of low-toxicity low-solubility particles, nanoparticles and fine particles, on epithelial cells in vitro: the role of surface area. Occup. Environ. Med. (2007);64:609–615. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.024802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pei B., Wang S., Guo X., Wang J., Yang G., Hang H., Wu L. Arsenite-induced germline apoptosis through a MAPK-dependent, p53-independent pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Chem. Res. Toxicol. (2008);21:1530–1535. doi: 10.1021/tx800074e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roh J.Y., Sim S.J., Yi J., Park K., Chung K.H., Ryu D.Y., Choi J. Ecotoxicity of silver nanoparticles on the soil nematode caenorhabditis elegans using functional ecotoxicogenomics. Environ. Sci. Technol. (2009);43:3933–3940. doi: 10.1021/es803477u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Troemel E.R., Chu S.W., Reinke V., Lee S.S., Ausubel F.M., Kim D.H. p38 MAPK regulates expression of immune response genes and contributes to longevity in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. (2006);2:e183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams P.L., Dusenbery D.B. Aquatic toxicity testing using the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. (1990);9:1285–1290. [Google Scholar]