Abstract

Silver nanoparticles (size: 7.9 ± 0.95 nm, dosage: 250 mg/kg) were orally administered to pregnant rats. At 4 days after parturition, four pups were randomly selected (one pup from one dam) and silver level in liver, kidney, lung and brain was determined by ICP-MS and electron microscope. As results, silver nanoparticles highly accumulated in the tissues of the pups. Silver level in the treated group was 132.4 ± 43.9 ng/g in the kidney (12.3 fold compared to control group), 37.3 ± 11.3 ng/g in the liver (7.9 fold), 42.0 ± 8.6 ng/g in the lung (5.9 fold), and 31.1 ± 4.3 ng/g in the brain (5.4 fold). This result suggested that the possible transfer of silver nanoparticles from pregnant dams to the fetus through mainly placenta.

Keywords: Silver nanoparticles, Pregnant rats, Placenta transfer, Accumulation in pups

With a rapid increase of nanoparticle applications, there is an urgent need for toxicologists to study nanotoxicity on the risk assessment of nanoproducts. Many consumer products of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) including medicines, water disinfectants, room sprays and fabrics may release nanoparticles that can be exposed to the human body (Benn et al., 2010). The exposed AgNPs can be absorbed into blood circulation, and accumulate in tissues including the liver, kidney, spleen and other organs (Kim et al., 2008; Tang et al., 2009). Recently, serum kinetics and organ distribution of AgNps by oral administration or intravenous injection have been studied. Bioavailability was reported to be about 4% in 10 mg/kg dosage (Park et al., 2011). Although the bioavailability of AgNPs through oral administration is very low, long term treatments may allow accumulation of nanoparticles in body organs. Furthermore, AgNPs administered to pregnant animals were found to be transferred to the fetus (Kulvietis et al., 2011). However, data on the possible transfer to fetus through the placenta barrier or other possible pathways are still limited. In this study, transfer of AgNPs from pregnant female rats to offspring was investigated.

The AgNPs coated with citrate were kindly provided by ABC NANOTECH (Daejeon, Korea). The size of the AgNPs was estimated to be 7.9 ± 0.95 nm based on the TEM image and the mean particle surface area was found to be 7.53 × 102 nm2/particle; whereas the mean particle mass and mean particle volume were found to be 2 × 10−17 g and 1.9 × 103 nm3, respectively. Sprague Dawley (SD) female rats (n > 4) were treated by oral administration of AgNPs (250 mg/kg) for 14 days before mating, during the mating period and gestation period, and finally 4 days after parturition. SD male rats (n > 4) were also treated with AgNPs (250 mg/kg) for 14 days before mating and during the mating period. The doses and treatment regimen was based on the OECD Test Guideline 422: Combined Repeated Dose Toxicity Study with the Reproduction/Developmental Toxicity Screening Tests, which recommends three dose-groups. In this study, the highest dosage of 250 mg/kg was selected among the three dosages (250, 125, and 62.5 mg/kg). Mating was confirmed by the microscopic finding of sperm in the virginal exudate. Data regarding the reproductive toxicity test were rule out in this study. Offspring were sacrificed 4 days after birth, and the organs of pups including the liver, kidney, lung and brain were obtained (total 4 offsprings, one offspring was chosen from one pregnant rat, respectively). All the animals used in this study were taken care of in accordance with the principles outlined in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” issued by the Animal Care and Committee of NVRQS (National Veterinary Research and Quarantine Service).

For the analysis of total silver, the samples (approximately 200 mg of each tissue) were digested in a mixed solution of 70% HNO3 (7 ml) and 30% H2O2 (1 ml) using the microwave digestion system (Milestone, Sorisole, Italy) under conditions of high temperature and pressure. After dilution of the acidic digested preparation with deionized water (1 : 11), the concentration of silver was analyzed using the ICP-MS (Elan6100/Perkin Elmer, USA) at Korean Basic Science Institute (KBSI, Seoul, Korea). Liver tissue was fixed with glutaradehyde and osmium tetroxide, and observed with a transmission electron microscope (JEOL, JEM01200 EX II). Student t-test was performed for the statistical analysis.

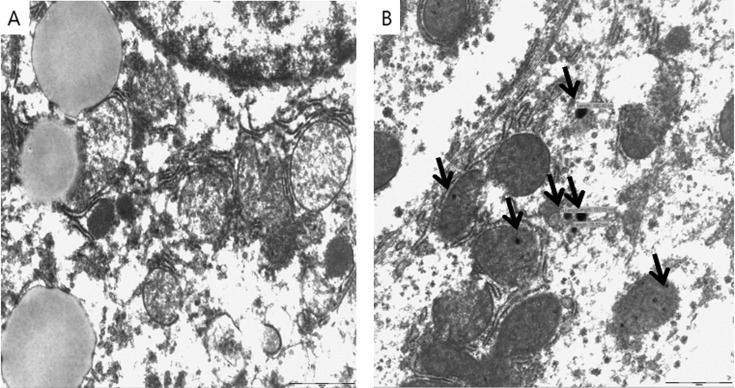

Pups were randomly selected from non-treated control dams and treated dams, respectively and tissue levels of AgNPs in pups (n = 4, one pub from one dam) was determined in liver, kidney, lung and brain. As shown in Table 1, accumulation of silver was observed in the tissues of respective organs in the offspring from the treated dams. The kidney seemed to be the main target for theion of AgNPs and exhibited higherion levels compared to the other tissues. Silver levels were 132.4 ± 43.9 ng/g in the kidney (12.3 fold compared to control group) and the levels were 37.3 ± 11.3 ng/g in the liver (7.9 fold), 42.0 ± 8.6 ng/g in the lung (5.9 fold), and 31.1 ± 4.3 ng/g in the brain (5.4 fold). Theed AgNPs were observed in the liver of pups by a transmission electron microscope (Fig. 1). This result suggested a possible transfer of AgNPs from pregnant dams to offspring mainly through the placenta or minor pathway of milk.

Table1.

Silver concentration in the organs of offspring (n = 4) sacrificed at 4 days after birth from dams treated with AgNPs (250 mg/kg) by oral administration of silver nanoparticles

| Liver | Kidney | Lung | Brain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 4.7 ± 0.59 | 10.8 ± 1.4 | 7.1 ± 2.1 | 5.8 ± 2.5 |

| AgNPs | 37.3 ± 11.3* | 132.4 ± 43.9* | 42.0 ± 8.6* | 31.1 ± 4.3* |

(unit : ng/g)

*; Statistically significant compared to control value (P < 0.01).

Fig. 1. Localization of AgNPs in the liver of offspring from pregnant dam treated with AgNPs by oral administration (250 mg/kg). Panel A and B are representative TEM images of 80 nm liver sections of offspring from the non-treated control group and the treated group, respectively. Representative AgNPs visible in the hepatocytes as black electron-dense spots were indicated by arrows.

In previous publications (Takeda et al., 2009; Menezes et al., 2011), titanium dioxide nanoparticles (25~70 nm) were administrated subcutaneously to pregnant mice at 3, 7, 10 and 14 days post-coitum and the nanoparticles were detected in the testes and brain of the offspring 6 weeks after birth. The authors suggested that nanoparticles may be delivered by a placental passage. They also hypothesized that the nanoparticles reached the fetal brain because they were administered before the full development of the bloodbrain barrier. In our study, AgNPs (7.9 ± 0.95 nm) were also identified in the brain of offspring, which means that AgNPs may reach the brain before the blood-brain barrier is formed in the fetus or they may directly pass the barrier. The AgNPs used in this study are capped with hydrophilic citrate which is hydrophilic but it seems that they have some kind of mechanism to pass the cellular lipid membrane and other barriers. Further studies are needed to investigate the detailed mechanisms of the transport system of AgNPs.

References

- 1.Benn T., Cavanagh B., Hristovski K., Posner J.D., Wester-hoff P. The release of nanosilver from consumer products used in the home. J. Environ. Qual. (2010);39:1875–1882. doi: 10.2134/jeq2009.0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim Y.S., Kim J.S., Cho H.S., Rha D.S., Kim J.M., Park J.D., Choi B.S., Lim R., Chang H.K., Chung Y.H., Kwon I.H., Jeong J., Han B.S., Yu I.J. Twenty-eight-day oral toxicity, genotoxicity, and gender-related tissue distribution of silver nanoparticles in Sprague-Dawley rats. Inhal. Toxicol. (2008);20:575–583. doi: 10.1080/08958370701874663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulvietis V., Zalgeviciene V., Didziapetriene J., Rotomskis R. Transport of nanoparticles through the placental barrier. Tohoku J. Exp. (2011);225:225–234. doi: 10.1620/tjem.225.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menezes V., Malek A., Keelan J.A. Nanoparticulate drug delivery in pregnancy: placental passage and fetal exposure. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. (2011);12:731–742. doi: 10.2174/138920111795471010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park K., Park E.J., Chun I.K., Choi K., Lee S.H., Yoon J., Lee B.C. Bioavailability and Toxicokinetics of Citratecoated Silver Nanoparticles in Rats. Arch. Pharm. Res. (2011);34:153–158. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0118-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeda K., Suzuki K.I., Ishihara A., Kubo-Irie M., Fujimoto R., Tabata M., Oshio S., Nihei Y., Ihara T., Sugamata M. Nanoparticles transferred from pregnant mice to their offspring can damage the genital and cranial nerve systems. J. Health Sci. (2009);55:95–102. doi: 10.1248/jhs.55.95. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang J., Xiong L., Wang S., Wang J., Liu L., Li J., Yuan F., Xi T. Distribution, translocation and accumulation of silver nanoparticles in rats. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. (2009);9:4924–4932. doi: 10.1248/jhs.55.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]