Abstract

Scleromyxedema is a rare progressive cutaneous mucinosis, usually associated with a systemic involvement and paraproteinemia. Its aetiology remains unknown. The therapeutic options include numerous treatment modalities, however, no standard treatment exists as the rarity of this disease prevents the execution of controlled therapeutic trials. This paper reports a case of a 38-year-old male with progressive scleromyxedema associated with gammopathy. Initially, the patient was treated with prednisolone and later etretinate was added to the therapeutic schedule with quite good clinical improvement. However, after 6 months of treatment, several adverse effects were observed: hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridaemia and cataract of the right eye. The patient was consulted by dermatologists in Warsaw and Gdansk as well as by a haematologist. The patient was excluded from oncological treatment. Melphalan therapy was not recommended as it is associated with very toxic side effects. IVIG treatment (intravenous immunoglobulin) was not initiated because of financial issues. As the disease progressed, treatment with plasmapheresis was introduced. The patient received 4 cycles of the therapy. It was well-tolerated by the patient and gave satisfactory, but temporary results. In order to obtain long-lasting improvement the patient was treated with IVIG (21.0 g/dose for 5 consecutive days). This treatment modality seems to have resulted in a more stable improvement.

Keywords: scleromyxedema, treatment, intravenous Immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis

Introduction

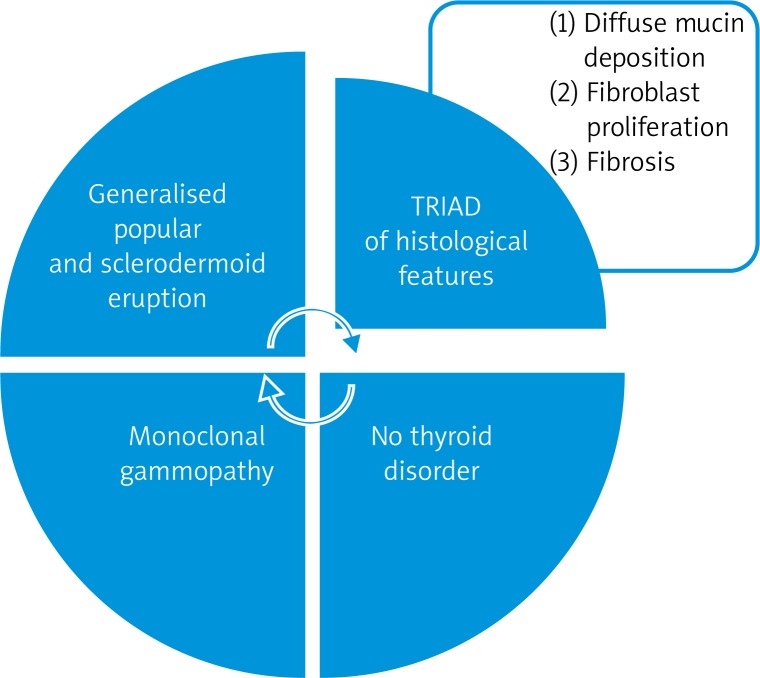

Scleromyxedema (SM) is a rare progressive cutaneous mucinosis usually associated with a systemic involvement and paraproteinemia. It was first defined by Arndt and Gottron (1954) [1], then redefined by Rongioletti and Rebora (2001), as a disease characterised by a generalised papular and sclerodermoid eruption, monoclonal gammopathy (mostly Ig-λ paraproteinemia) and a triad of histological features: presence of mucin deposition within the upper and mid reticular dermis, fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis with the absence of a thyroid disorder [2] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagnostic criteria of scleromyxedema

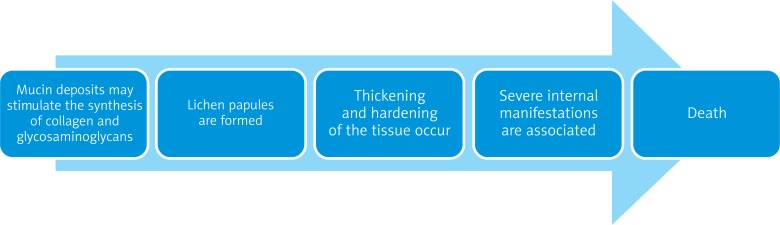

Scleromyxedema is a severe disorder that may be fatal. It is characterised by an excessive deposition of mucin in the connective tissue [3]. The deposits may stimulate the synthesis of collagen and glycosaminoglycans [1]. As a result, lichenoid papules are formed which cause thickening and hardening of the tissue [4]. Scleromyxedema has a chronic, disabling course because it is often associated with a systemic involvement of internal organs. Scleromyxedema is thought to have three main clinicopathological subsets: local, generalised and atypical [3]. The generalised form is often referred to as the “generalised lichen myxedematosus”, and its course is much more severe than that of the other forms (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Chronic, potentially fatal course of scleromyxedema

The prevalence of SM is equal in men and women. No standard treatment exists as the rarity of the disease has prevented the execution of controlled therapeutic trials. Until 2009, only 150 cases of patients suffering from scleromyxoedema were reported [5].

The skin appears to be elephant-like and forms linear folds. The papules tend to group in the neck and forehead area. Histopathological examination reveals numerous mucin deposits in papules and sclerotic malformations, which consist of thickened collagen fibres. The mucin deposits are subtle in these lesions [1].

Numerous internal manifestations may occur in SM [6–8] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Internal manifestations of scleromyxedema

| Type of involvement | Manifestation |

|---|---|

| Muscular | Proximal myopathy, joint contractures, muscle weakness |

| Neurological | Encephalopathy, peripheral neuropathy, coma |

| Rheumatological | Joint pain, migrating arthritis, sclerodactyly, seronegative polyarthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome |

| Pulmonary | Obstructive/restrictive lung disease, pulmonary hypertension |

| Renal | Renal insufficiency |

| Cardiovascular | Myocardial infarction, hypertension, atherosclerosis |

| Ophthalmological | Corneal deposits, thinning of the eyelid, ectropion |

Case report

We report a case of a 38-year-old man with a 1.5-year history of scleromyxedema typically associated with light chain λ IgG monoclonal gammopathy. He was first hospitalized in February 2011 due to severe pruritus of his feet and shanks, elbow, and carpal joint pain and sclerodactyly. Simultaneously erythema and small papules appeared on the skin of his face.

Cutaneous examination revealed small, symmetric, disseminated papules (of 1 mm in diameter). Waxy and firm papules were localised mainly on both arms. The patient also presented excessive and diffuse thickening of the skin on the face, especially surrounding the lips, which later led to facial expression impairment.

Radiological and ultrasonographic examinations were also performed to exclude any systemic involvement of the disease (chest X-ray, USG of abdomen). In laboratory investigation complete blood count was normal. Serum analysis indicated hyperproteinemia: IgG monoclonal gammopathy with λ light chains were present. Bence-Jones protein was detected, however, further investigations excluded haematological disorders. Urine analysis was normal. Based on clinical manifestations, and histopathological and laboratory data, the diagnosis of scleromyxoedema with associated IgG-λ was obtained.

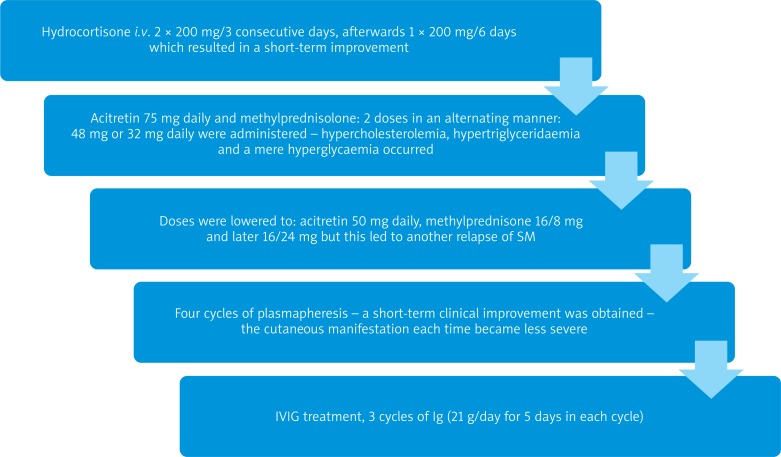

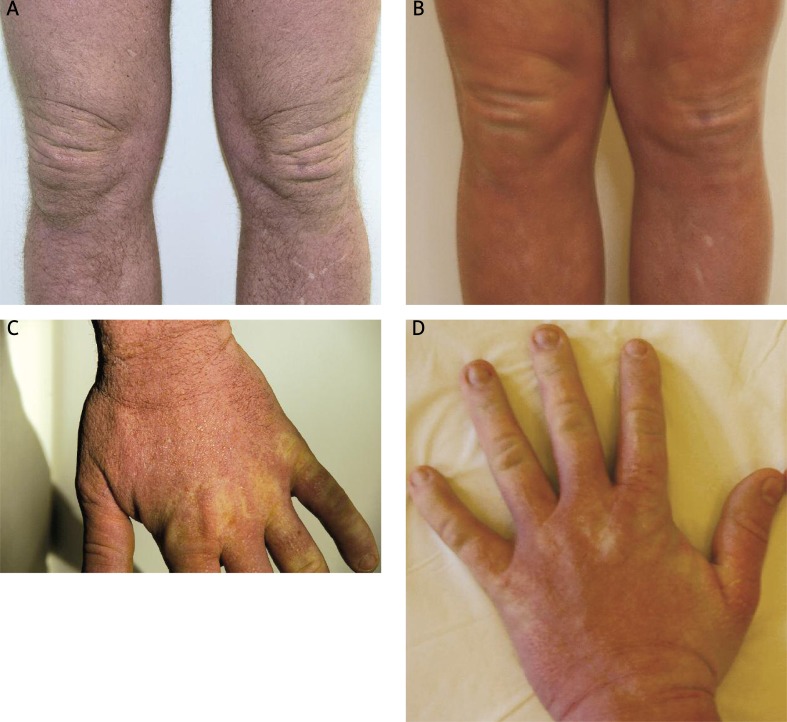

As scleromyxedema leads to systemic involvement, the patient was consulted by several specialists: a haematologist, cardiologist, neurologist, ophthalmologist, internal medicine doctor and several dermatologists. The haematologist disqualified the patient from treatment with melphalan. Therapy before hospitalisation included oral prednisolone, oral antihistaminic drugs and topical steroids but remained ineffective. Treatment was started with hydrocortisone i.v. 2 × 200 mg/3 consecutive days, afterwards 1 × 200 mg/6 days, which resulted in a slight improvement – erythema started to fade. After a relapse of the disease several weeks later, we introduced a combination of oral acitretin 75 mg daily and methylprednisolone: 2 doses in an alternating manner 48 mg or 32 mg daily were administered. This stopped the progression of the disease. However, as a result of steroid and retinoid administration, the patient presented hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridaemia and mere hyperglycaemia. This is why the doses were lowered to: acitretin 50 mg daily, methylprednisolone 16/8 mg and later 16/24 mg, but this led to another relapse of clinical symptoms. Then, plasmapheresis was started. The patient received a total of 4 cycles of plasmapheresis. Each cycle consisted of 4-5 procedures of plasmapheresis. Every course resulted in short-term clinical improvement – cutaneous manifestation each time became less severe. In order to attempt to achieve remission, IVIG treatment was started (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Different treatment modalities used in the therapy of our patient with scleromyxedema

Figure 4 A-D.

Clinical appearance directly prior to initiation of IVIG and after 3 cycles of IVIG – skin thickness deceased, papules became less visible

Table 2.

Treatment modalities of scleromyxedema

| Treatment modality | References |

|---|---|

| Systemic corticosteroids | [10] |

| Cyclophosphamide | [11, 12] |

| Melphalan | [15] |

| Interferon α | [16] |

| Cyclosporine A | [17, 18] |

| Plasmapheresis | [19, 20] |

| Methotrexate | [21] |

| Chlorambucil joined with PUVA | [22] |

| Surgical intervention | [23] |

| 2-chlordeoxyadenosine | [24] |

| Retinoids | [25] |

| Mucopolysaccharides (thiomucase) | [26] |

| Thalidomide | [7, 14] |

| Immunoglobulins | [6, 27–30] |

| Autologous stem cell transplantation | [13, 31, 32] |

| Biological treatment – bortezomib | [13, 14] |

Discussion

Causal treatment of scleromyxedema is unavailable, as the aetiology is still unclear [9]. The severe course of the disease requires very aggressive treatment and long-term maintenance therapy is necessary in most cases [7].

According to the literature, a successful therapy with relatively long-term effects and few side effects involves the use of IVIG [28, 29]. It is considered to be the best therapeutic option as it is associated with relatively few side effects [27]. Plasmapheresis remains effective only in a short-time perspective and leads to relapses. For this reason we started IVIG treatment. We received a relatively good and longer lasting response to this treatment modality: the papules and generalised sclerodermoid eruption became less visible. The progression of the disease was stopped. However, from a financial aspect, this treatment modality may be challenging.

The chronic course of this disease affects the patient mentally, thus psychological or psychiatric therapy may also be introduced in order to improve the results of systemic treatment.

References

- 1.Brown-Falco O, Burgdorf WHC, Wolff HH, Landthaaler M. Lublin: Czelej; 2011. Dermatology; pp. 1289–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxodematosus and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273–81. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.111630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serdar ZA, Yasar SP, Erfan GT, Gunes P. Generalized papular sclerodermoid eruption: scleromyxedema. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2010;76:592–2. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.69096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binitha MP, Nandakumar G, Thomas D. Suspected cardiac toxcicity to intravenous immunoglobulin used for treatment of scleromyxedema. Indian J Dermatol Leprol. 2008;74:248–50. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.41372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta V, Balachandran C, Raghavendra R. Arndt Gottron Scleromyxedema: successful response to treatment with steroid minipulse and methotrexate. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:193–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.53183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manousaridis I, Loeser C, Goerdt S, Hassel JC. Managing scleromyxedema with intravenous immunoglobulin: accute worsening of scleromyxedema with biclonal gammopathy. Acta Dermatoven APA. 2010;19:15–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laimer M, Namberger K, Massone C, et al. Vincristine, idarubicin, dexamethasone and thalidomide in scleromyxedema. Acta Derm Venerol. 2009;89:631–5. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maciejewska-Radomska A, Sokołowska-Wojdylo M, Wilkowska A, et al. Scleromyxoedema in a 70-year-old woman: case report and review of the literature. Postep Derm Alergol. 2011;28:63–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuldeep CM, Mittal AK, Gupta LK, et al. Successful treatment of scleromyxedema with dexamethasone cyclophophamide pulse therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:44–5. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.13787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rayson D, Lust JA, Duncan A, Su WP. Scleromyxedema: a complete response to prednisone. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:481–4. doi: 10.4065/74.5.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aberer W, Wolff K. Scleromyxedema: immunosuppressive therapy with cyclophosphamide. Hautarzt. 1988;39:277–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuldeep CM, Mittal AK, Gupta LK, et al. Successful treatment of scleromyxedema with dexamethasone cyclophosphamide pulse therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:44–5. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.13787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Migkou M, Gkotzamanidou M, Terpos E, et al. Response to bortezomib of a patient with scleromyxedema refractory to other therapies. Leuk Res. 2011;35:209–11. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cañueto J, Labrador J, Román C, et al. The combination of bortezomib and dexamethasone is an efficient therapy for relapsed/refractory scleromyxedema: a rare disease with new clinical insights. Eur J Haematol. 2012;88:450–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2012.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dinneen AM, Dicken CH. Scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tschen JA, Chang JR. Scleromyxedema: treatment with interferon alfa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:303–7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krajnc I. Arndt-Gottron scleromyxedema. Summary of 2 years treatment. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1997;109:960–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saigoh S, Tashiro A, Fujita S, Matsui M. Successful treatment of intractable scleromyxedema with cyclosporin A. Dermatology. 2003;207:410–1. doi: 10.1159/000074127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westheim AI, Lookingbill DP. Plasmapheresis in a patient with scleromyxedema. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:786–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keong CH, Asaka Y, Fukuro S, et al. Successful treatment of scleromyxedema with plasmapheresis and immunosuppression. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:842–4. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta V, Balachandran C, Rao R. Arndt Gottron scleromyxedema: successful response to treatment with steroid minipulse and methotrexate. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:193–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.53183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schirren CG, Betke M, Eckert F, Przybilla B. Arndt-Gottron scleromyxedema. Case report and review of therapeutic possibilities. Hautarzt. 1992;43:152–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acikel C, Karagoz H, Kucukodaci Z. Surgical treatment of facial disfigurement due to lichen myxedematosus. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:875–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis LS, Sanal S, Sangueza OP. Treatment of scleromyxedema with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:288–90. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90650-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milam CP, Cohen LE, Frenske NA, Ling NS. Scleromyxedema: therapeutic response to isotretinoin in three patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:469–77. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cosgarea R, Cosgarea M, Turcu T. Scleromyxedema with laryngeal changes. Beneficial results of the treatment with mucopolysaccharidases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1994;121:159–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wojas-Pelc A, Blaszczyk M, Glinska M, Jablonska S. Tumorous variant of scleromyxedema. Successful therapy with. JEADV. 2005;19:462–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blum M, Wigley FM, Hummers LK. Scleromyxedema: a case series of highlighting long-term outcomes of treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87:10–20. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181630835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bidier M, Zschoche C, Gholam P, et al. Scleromyxoedema: clinical follow-up after successfu treatment with high-dose immunoglobulins reveals different long-term outcomes. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:408–9. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Righi A, Schiavon F, Jablonska S, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulins control scleromyxoedema. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:59–61. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iranzo P, López-Lerma I, Bladé J, et al. Scleromyxoedema treated with autologous stem cell transplantation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:129–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Illa I, de la Torre C, Rojas-Garcia R, et al. Steady remission of scleromyxedema 3 years after autologous stem cell transplantation: an in vivo and in vitro study. Blood. 2006;108:773–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]