Abstract

Introduction

Photoaging is the superposition of chronic ultraviolet (UV)-induced damage on intrinsic aging. Telomere length is a molecular marker of cell aging, and genomic instability due to telomere shortening has been linked to several aging-related diseases.

Aim

To explore the effects of different doses of ultraviolet A (UVA) on the length of telomeres in human skin fibroblasts and partly reveal the mechanism of skin photoaging initiated by UVA irradiation.

Material and methods

Primary cultured human skin fibroblasts were irradiated with different doses of UVA light. Cell viability, cell cycle phase, β-galactosidase, and the length of telomeres were assessed by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay, flow cytometry, cytochemical staining, and real-time polymerase chain reactions, respectively.

Results

After UVA irradiation, inhibited proliferation, S phase accumulation and increased expression of senescence-associated β-galactosidase were observed in cultured fibroblasts. Moreover, the length of telomeres in UVA-treated cells was shortened in a dose-dependent manner as compared to controls (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

These results suggest that telomere length in human dermal fibroblasts can be shortened by a single high dosage of UVA radiation, and that acute photodamage might contribute to early photoaging in human skin via rapid telomere shortening. This study potentially provides the basis for better understanding of the molecular mechanism of photoaging.

Keywords: photoaging, human fibroblast, ultraviolet A, cell cycle, telomere

Introduction

Photoaging is the superposition of chronic ultraviolet (UV)-induced damage on intrinsic aging. It accounts for denaturation of dermal elastic fibers and characteristic deep wrinkles, and is a well-known factor leading to skin cancer [1, 2].

Telomere length is a molecular marker of cell aging, and genomic instability due to telomere shortening has been linked to aging-related diseases, especially cancer [3]. It has been postulated that telomere shortening played an important role in photoaging [4, 5]. Recent studies have suggested that intrinsic aging and photoaging share a common pathway involving telomere-generated signaling that is responsible for most clinical manifestations of skin aging [1, 4, 6]. However, an earlier study showed that telomere length did not differ significantly between sun-exposed and sun-protected skin [7, 8]. Thus, whether the length of telomere is shortened in photoaging remains unclear.

Aim

Ultraviolet A (UVA), the principal component of solar radiation, penetrates deep into the dermis [9]. In this study, we investigated the photodamaging effects of different doses of UVA radiation on cultured human skin fibroblasts (HSFs), focusing on proliferation, cell cycle, senescence-associated β-galactosidase expression and telomere length [10].

Material and methods

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital. All the parents of all donors provided signed written consent.

Cell culture

Primary HSF cultures were obtained by outgrowth from the foreskins of healthy human donors aged 3-10 years [11]. Tissue specimens were washed in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) with 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Gibco), minced finely and allowed to adhere to plastic flasks. Cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Scientific HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2–95% air [12, 13]. When the cells reached 80% confluence, subculture was conducted at a split ratio of 1: 3. Cells were utilized between passages 3 and 5.

UVA irradiation

Human skin fibroblasts were inoculated in 6- and 96-well plates and 35 mm dishes, cultured to 80% confluence and then irradiated with UVA. Before irradiation, the culture medium was replaced by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco). A UVA desktop apparatus (Sigma High-tech, Shanghai, China) was used as the light source with a spectrum of 320-400 nm as certified by the manufacturer. A 6-mm thick glass plate was used to block UVB emissions. UVA intensity was measured using a digital radiometer (Sigma, Shanghai, China). The exposure distance was 20 cm. During irradiation, the plates or dishes were cooled on ice to avoid cell damage from heating. After irradiation, the cells were immediately further incubated in fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cell viability and other tests were performed 24 h post-irradiation. Cells in the control group were treated the same as the irradiated cells except for the absence of UVA irradiation. Four doses of UVA were used in this study, including 5, 10, 15 and 20 J/cm2.

Cell viability measurement

To determine cell viability, a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; Gibco) assay was performed. HSFs (2 × 103 per well) were incubated in 96-well plates overnight before irradiation to allow attachment to the wells. The cells were incubated post-irradiation for 24 h. MTT (20 µl of 5 mg/ml) was added to each well and the cells were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The supernatant was then removed and 100 µl dimethyl sulfoxide was added. The optical density was measured on a microplate reader (Spectra Max 190; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 490 nm to determine the viable cell percentage.

Cell cycle analysis

After UVA irradiation, HSFs were incubated for 24 h before trypsinization and centrifugation. Collected cells were washed twice with cold PBS and fixed in 70% ethanol at 4°C overnight. The cells were then treated with 50 mg/l RNase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and stained with 50 mg/l propidium iodide (Sigma) in the dark at 37°C for 30 min. The cell cycle was analyzed using flow cytometry (Cytomics FC500; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton CA, USA).

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining

Human skin fibroblasts were incubated for 24 h after UVA irradiation, and then trypsinized and further incubated for 24 h in 6-well plates (1 × 104 per well) (BD Falcon, Los Angeles, CA, USA). A Senescence β-Galactosidase Staining Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was used as previously described [14]. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS, fixed for 15 min in 3% formaldehyde, rinsed three times with PBS and stained at 37°C with 1 ml X-Gal solution overnight. Staining was evident in 12-16 h. Visual fields were selected randomly and up to 500 cells were counted at 200× magnification. β-Galactosidase-positive cells were expressed as a percentage of the total number of counted cells.

DNA extraction and relative quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Relative quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis was performed 24 h post-irradiation. To measure telomere length, total DNA was extracted using a Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Dongsheng Biotech, Guangzhou, China) according to the manufacturer's manual. Genomic DNA was quantified using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Smart Spectro 2000; LaMotte, Chestertown, MD, USA).

Mean telomere length was determined using quantitative real-time PCR as described previously [15]. This method measures the average ratio between the telomere repeat copy number and that of a single-copy gene (36B4; T/S ratio) in each sample. The T/S ratio is proportional to the average telomere length, and the relative telomere length can therefore be calculated quantitatively. Real-time PCR reactions were performed using an iCycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Duplicate DNA samples were amplified in parallel in 20 µl PCR reactions containing 35 ng sample DNA, 10 µl Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and 1 µM of primers specific for telomeres (1: 5’-GGTTTTTGAGGGTGAGGGTGAGGGTGAGGGTGAGGGT-3’; 2: 5’-TCCCGACTATCCCTATCCCTATCCCTATCC- CTATCCCTA-3’) or the single-copy gene (36B4u: 5’-CAGCAA-GTGGGAAGGTGTAATCC-3’; 36B4d: 5’-CCCATTCTATCATCAACGGGTACAA-3’).

Thermal cycling began with 95°C incubation for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 20 s and 54°C for 2 min (for telomeres) or 58°C for 1 min (for 36B4). Standard curves were established for each assay using serial dilutions of sample DNA (five concentrations, dilution factor ∼2). Linear correlation coefficients (r 2) for telomere and 36B4 standard curves were 0.98 and 0.99, respectively. Relative telomere length was calculated from T/S ratio = 2–ΔCt, where ΔCt = Ct telomere – Ct 36B4.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times. The results were expressed as mean ± SD. Data were analyzed using SPSS 13.0. Value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Student's t-test was used to compare two means. To compare multiple means, one-way analysis of variance in conjunction with Dunnett's test was performed.

Results

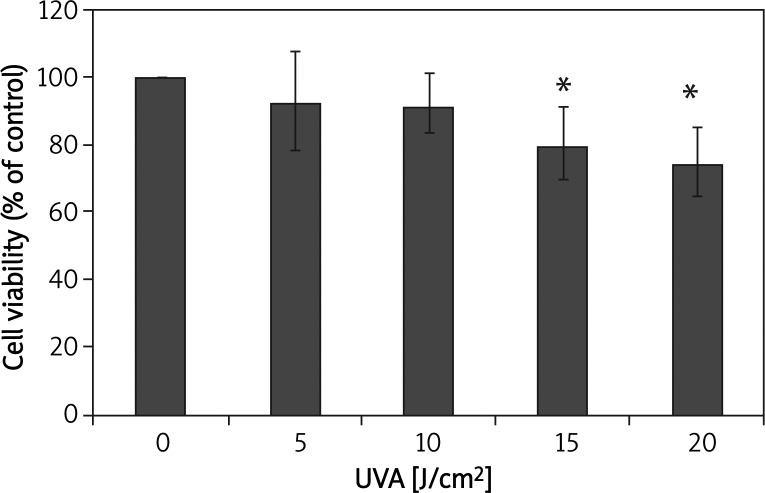

UVA irradiation decreases cell viability

The cytotoxicity of UVA irradiation was evaluated by MTT assay at 24 h post-irradiation. Compared with negative controls, the viability of irradiated fibroblasts was decreased in a dose-dependent manner. Inhibition of proliferation was observed in cells exposed to a dose of 15 J/cm2 or 20 J/cm2 (p < 0.05; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ultraviolet A irradiation decreases the viability of cultured HSFs at 24 h post-irradiation

*p < 0.05 compared with controls

UVA irradiation induces cell cycle arrest in human skin fibroblasts

The dependence of HSF cell cycle distribution on a UVA dose at 24 h post-irradiation was illustrated by a typical series of flow cytometry histograms (Figure 2). Compared with non-irradiated controls, the proportion of UVA-irradiated fibroblasts in S phase was significantly increased at 24 h (p < 0.05), whereas the proportion in G2 phase was significantly decreased (p < 0.05). This effect was dose dependent (Table 1). Moreover, a statistically significant difference in the proportion of cells in G1 phase was seen between the 20 J/cm2 group and negative controls (Table 1).

Figure 2.

The cell cycle distribution of cultured HSFs depends on ultraviolet A dose at 24 h post-irradiation: A – controls, B – 5 J/cm2, C – 10 J/cm2, D – 15 J/cm2, E – 20 J/cm2

Table 1.

Effects of ultraviolet A irradiation on the cell cycle of cultured HSFs at 24 h post-irradiation

| Group | Dose [J/cm2] | %G1 | %S | %G2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0 | 74.43 ±2.84 | 13.23 ±2.02 | 12.33 ±0.82 |

| UVA | 5 | 69.93 ±1.91 | 24.6 ±1.13* | 5.48 ±0.78* |

| UVA | 10 | 70.23 ±1.33 | 26.46 ±1.51* | 3.29 ±0.26* |

| UVA | 15 | 68.35 ±1.61 | 31.26 ±1.36* | 0.37 ±0.26* |

| UVA | 20 | 63.53 ±0.96* | 36.23 ±1.11* | 0.23 ±0.31* |

p < 0.05, compared with control, UVA – ultraviolet A

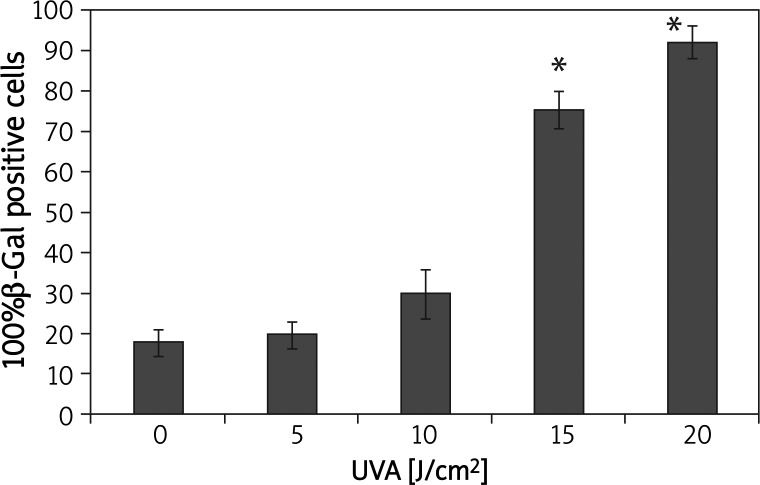

UVA irradiation increases the expression of β-galactosidase in human skin fibroblasts

β-Galactosidase expression was increased in a dose-dependent manner after UVA irradiation (Figure 3). UVA doses of 15 J/cm2 and 20 J/cm2 induced a significant increase in β-galactosidase activity compared with that in the control group (p < 0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Ultraviolet A irradiation increased the expression of senescence-associated β-galactosidase in HSFs

*p < 0.05 compared with controls

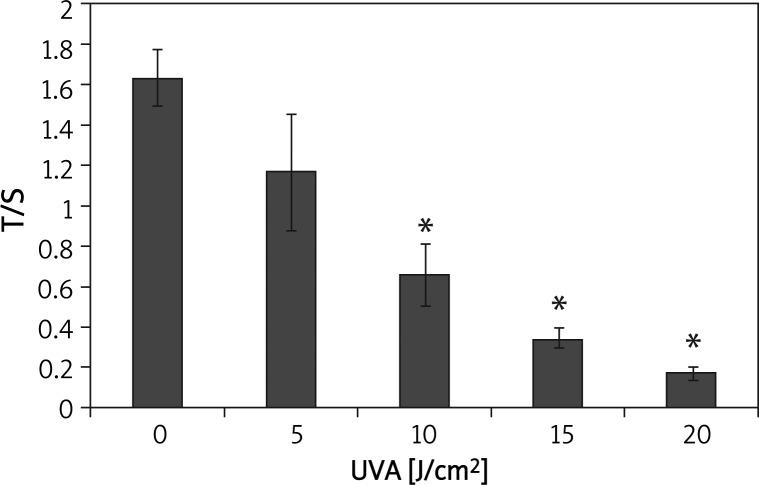

UVA irradiation decreases mean telomere length in human skin fibroblasts

After incubation for 24 h post-irradiation, mean telomere length was evaluated using relative quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and was found to be reduced in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4). There was a statistically significant difference between the high dose groups (10, 15 and 20 J/cm2) and the sham-irradiated controls (p < 0.05) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Ultraviolet A irradiation decreased the mean length of telomeres in HSFs at 24 h post-irradiation

*p < 0.05 compared with controls

Discussion

The major findings of this study are as follows. Firstly, UVA irradiation decreases cell viability. Secondly, UVA irradiation induces cell cycle arrest in HSFs. Thirdly, UVA irradiation increases the expression of β-galactosidase in HSFs. Finally, UVA irradiation decreases mean telomere length in HSFs.

UVA doses below 10 J/cm2 administered to fibroblasts in vitro are of physiological relevance as it is similar to the dose at which human skin is exposed in sunlight for 15-30 min during summer, at noon at a latitude of 30–35°N [16]. In this study, we found that the viability of cultured fibroblasts decreased as the intensity of irradiation increased. Doses less than 10 J/cm2 did not affect proliferation, suggesting that cell repair mechanisms can overcome the stress generated by irradiation at this intensity. However, at doses over 10 J/cm2, the proliferation of fibroblast was inhibited, suggesting that the cytotoxicity induced by a larger dose of UVA cannot be repaired completely.

Features of cell senescence, including growth arrest and increased β-galactosidase expression, were also observed following a single large dose of UVA. Progression through S phase is slowed in eukaryotic cells with damaged DNA, allowing time for DNA repair before the genome is replicated [17]. The S-M checkpoint depends on completion of DNA synthesis, preventing mitosis in the presence of incompletely replicated DNA due to replication inhibitors or DNA damage that blocks replication fork progression [18]. In our study, UVA irradiation of cultured fibroblasts resulted in cell cycle alterations, especially S phase accumulation, suggesting that UVA inhibits cell proliferation by inducing an S phase delay. Our data are consistent with a previous report [19] on the role of the DNA damage checkpoint response in UVA-induced inhibition of DNA replication. β-Galactosidase has been widely used to demonstrate the onset of cell senescence [20]. In this study, in groups irradiated with UVA doses higher than 10 J/cm2, the expression of the enzyme was significantly increased. Here, we confirm that cytotoxicity induced by a single large dose of UVA may accelerate the aging processes.

We found that mean telomere length in UVA-irradiated fibroblasts decreased with increased doses, and a significant difference was observed between the high dosage groups and negative controls. Thus, acute photodamage might contribute to early photoaging in human skin as a consequence of rapid telomere shortening. Telomere dependent replicative senescence is an established stress-damage response [21]. UVA causes oxidative stress indirectly via reactive oxygen species generated after the absorption of light energy [22, 23], and oxidative stress may lead to telomere shortening [24, 25]. When telomeres reach a critical length, loop disruption may occur naturally [26], increasing the probability of telomere uncapping. It remains controversial whether telomere shortening results from accumulation of DNA damage at the telomere or the lack of certain repair mechanisms within human chromosomal DNA. However, recent data suggest that telomere-initiated senescence reflects a DNA damage checkpoint response that is activated with a direct contribution from dysfunctional telomeres [27]. The signaling pathway connecting telomere uncapping and replicative senescence appears to be the same as that activated by DNA damage [21].

Conclusions

Telomere length in human dermal fibroblasts can be shortened by a single high dosage of UVA radiation, and that acute photodamage might contribute to early photoaging in human skin via rapid telomere shortening. This study potentially provides the basis for better understanding of the molecular mechanism of photoaging.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Programs for Basic Research and Application of Sichuan China (No. 2010JY0061) and by the Scientific Research Starting Foundation for Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, Ministry of Education, China (Grant No. [2011] 508).

References

- 1.Yaar M, Gilchrest BA. Photoageing: mechanism, prevention and therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:874–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenerowicz D, Silny W, Dańczak-Pazdrowska A, et al. Environmental factors and allergic diseases. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19:475–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han J, Qureshi AA, Prescott J, et al. A prospective study of telomere length and the risk of skin cancer. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:415–21. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosmadaki MG, Gilchrest BA. The role of telomeres in skin aging/photoaging. Micron. 2004;35:155–9. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osmola-Mańkowska A, Silny W, Dańczak-Pazdrowska A, et al. The sun – our friend or foe? Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19:805–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumann L. Skin ageing and its treatment. J Pathol. 2007;211:241–51. doi: 10.1002/path.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugimoto M, Yamashita R, Ueda M. Telomere length of the skin in association with chronological aging and photoaging. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;43:43–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Śpiewak R. The substantial differences between photoallergic and phototoxic reactions. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19:888–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patil CK, Mian IS, Campisi J. The thorny path linking cellular senescence to organismal aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:1040–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Oliveira RF, Oliveira DAAP, Soares CP. Effect of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on l929 fibroblasts. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:224–9. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2011.22071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleischmajer R, Perlish JS, Krieg T, et al. Variability in collagen and fibronectin synthesis by scleroderma fibroblasts in primary culture. J Invest Dermatol. 1981;76:400–3. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12520933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayreuther K, Rodemann HP, Hommel R, et al. Human skin fibroblasts in vitro differentiate along a terminal cell lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5112–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makpol S, Jam FA, Yusof YAM, Ngah WZW. Modulation of collagen synthesis and its gene expression in human skin fibroblasts by tocotrienol-rich fraction. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:889–95. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2011.25567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9363–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berneburg M, Grether-Beck S, Kurten V, et al. Singlet oxygen mediates the UVA-induced generation of the photoaging-associated mitochondrial common deletion. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15345–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartek J, Lukas C, Lukas J. Checking on DNA damage in S phase. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:792–804. doi: 10.1038/nrm1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petermann E, Caldecott KW. Evidence that the ATR/Chk1 pathway maintains normal replication fork progression during unperturbed S phase. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2203–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.19.3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girard PM, Pozzebon M, Delacote F, et al. Inhibition of S-phase progression triggered by UVA-induced ROS does not require a functional DNA damage checkpoint response in mammalian cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:1500–16. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang NC, Hu ML. A fluorimetric method using fluorescein di-beta-D-galactopyranoside for quantifying the senescence-associated beta-galactosidase activity in human foreskin fibroblast Hs68 cells. Anal Biochem. 2004;325:337–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Zglinicki T, Saretzki G, Ladhoff J, et al. Human cell senescence as a DNA damage response. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berneburg M, Plettenberg H, Medve-Konig K, et al. Induction of the photoaging-associated mitochondrial common deletion in vivo in normal human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:1277–83. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kielbassa C, Roza L, Epe B. Wavelength dependence of oxidative DNA damage induced by UV and visible light. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:811–6. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oikawa S, Kawanishi S. Site-specific DNA damage at GGG sequence by oxidative stress may accelerate telomere shortening. Febs Lett. 1999;453:365–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00748-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houben JM, Moonen HJ, van Schooten FJ, et al. Telomere length assessment: biomarker of chronic oxidative stress? Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:235–46. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li GZ, Eller MS, Firoozabadi R, et al. Evidence that exposure of the telomere 3’ overhang sequence induces senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:527–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0235444100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.d'Adda di Fagagna F, Reaper PM, Clay-Farrace L, et al. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature. 2003;426:194–8. doi: 10.1038/nature02118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]