Abstract

Retinoids are biologically active derivatives of vitamin A modulating cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and altering the immune response. They have been used for years in therapy of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL) but the exact mechanism of retinoids’ action is unclear. It is based on the presence of specific receptors’ families, mediating the biological effects of retinoids on the tumor cells: retinoic acid receptor (RAR) and retinoic X receptor (RXR). Orally administrated bexarotene, the first synthetic selective RXR retinoid, was revealed to be active against the cutaneous manifestation of CTCL. The toxicity profile caused by bexarotene seems to be more limited to laboratory values and better tolerated than classical retinoids, but generally associated with more severe grades of toxicity. Both selective retinoic acid receptor- and retinoic X receptor-mediated retinoids have modest objective response rates and, therefore, most likely will have limited impact as monotherapeutic agents. However, the immunomodulatory effects of RAR and RXR retinoids provide a rational basis for using retinoids in combination with other biologic immune response modifiers, phototherapy and radiotherapy. The authors reviewed the literature on the results of the use of retinoids and rexinoids in patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome.

Keywords: cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, retinoids, rexinoids, retinoic X receptor, retinoic acid receptor

Introduction

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL) are rare lymphoproliferative disorders derived from the mature T helper cells. The CTCL can present as an indolent or aggressive process involving skin, lymph nodes, blood and, secondary, the internal organs. The great diversity and low annual incidence rate seems to be the main reason for difficulties in establishing the best therapeutic options. The best known subtype, mycosis fungoides (MF), has been the most frequent form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas representing 60% of all CTCL cases; more aggressive Sézary syndrome (SS) occurs less frequently (5%) [1–7].

Cutaneous T-cell lyfemale F – 2: 1) [8]. The course of the disease varies widely and depends on the patient age and the presence of extracutaneous symptoms, what has been clearly classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) [9]. Most of CTCLs, because of mild course, like MF in the early stage, lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) or cutaneous anaplastic T-cell lymphomas (C-ALCL), requires only skin-directed therapies (SDT). However, the patients with more aggressive variants, such as SS, or those refractory to SDT (e.g. syringotropic and pilotropic mycosis fungoides), require systemic therapies, including chemotherapy (Tables 1 and 2) [10].

Table 1.

Mycosis fungoides treatment: the WHO-EORTC recommendations

| Stage | First-line treatment | Second-line treatment |

|---|---|---|

| IA, IB, IIA | Topical glucocorticosteroids (high potency), topical nitrogen mustard (NH2), Carmustine (BCNU), PUVA, UVB, TSEB | Bexarotene, INF-α (monotherapy), denileukin diftitox, methotrexate (low doses), romidepsin, vorinostat, panobinostat, bortezomib, INF-α + PUVA, retinoids + PUVA, bexarotene + PUVA |

| IIB | PUVA + INF-α, retinoids + INF-α, PUVA + retinoids | Bexarotene, romidepsin, vorinostat, panobinostat, bortezomib, denileukin diftitox, systemic chemotherapy |

| III | PUVA + INF-α, INF-α, methotrexate, PUVA + retinoids, extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) | Bexarotene, romidepsin, vorinostat, panobinostat, bortezomib, denileukin diftitox, systemic chemotherapy |

| IVA, IVB | Systemic chemotherapy, TSEB, superficial X-irradiation, bexarotene, romidepsin, vorinostat, panobinostat, bortezomib, denileukin diftitox, INF-α, alemtuzumab, methotrexate (low doses) | |

PUVA – psoralen and phototherapy UVA, INF – interferon, TSEB – total skin electron beam therapy

Table 2.

Sézary syndrome treatment: the WHO-EORTC recommendations

| First-line treatment | Second-line treatment |

|---|---|

| ECP, INF-α, denileukin diftitox, chlorambucil + prednisone | Bexarotene, romidepsin, vorinostat, panobinostat, bortezomib, alemtuzumab, methotrexate, systemic chemotherapy |

ECP – extracorporeal photopheresis, INF – interferon

Retinoids, their receptors and mechanism of action

Retinoids seem to have a strong position among the therapeutic options recommended by WHO and EORTC in primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. As biological modifiers they have been used in CTCL in every stage for over three decades [11]. As derivatives of vitamin A, they modulate cell proliferation, differentiation and immunoregulation of epithelial cells and the mononuclear skin infiltrate [12, 13]. It is believed that retinoids may also induce cellular apoptosis and DNA fragmentation in sensitive T-cell lines [14]. The first generation of vitamin A analogues were tretinoin (all-trans-retinoic acid) and isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoin), followed by the second generation of retinoids: etretinate, acitretin, and a new aromatic retinoid (arotenoid) of the third generation: bexarotene [15].

The biologic effects of retinoids are mediated by two distinct families of intracellular receptors: retinoic acid receptors (RARs) and retinoic X receptors (RXR). Three subtypes, α, β, γ, have been identified for both RAR and RXR proteins [16].

The receptors for retinoids belong to a larger superfamily of receptors for steroids, as well as for thyroid hormone receptors (TR) and vitamin D receptors (VDR) (Table 3, Figure 1) what can lead to numerous side effects [17].

Table 3.

Human nuclear receptors and their active ligands

| Receptor | Ligand |

|---|---|

| All-trans retinoic acid receptor α (RARα) All-trans retinoic acid receptor β (RARβ) All-trans retinoic acid receptor γ (RARγ) |

All-trans retinoic acid, 9-cis retinoic acid, retinoids All-trans retinoic acid, 9-cis retinoic acid, retinoids All-trans retinoic acid, 9-cis retinoic acid, retinoids |

| 9-cis retinoic acid receptor α (RXRα) 9-cis retinoic acid receptor β (RXRβ) 9-cis retinoic acid receptor γ (RXRγ) |

9-cis retinoic acid, rexinoids 9-cis retinoic acid, rexinoids 9-cis retinoic acid, rexinoids |

| Thyroid hormone receptor α (TRα) Thyroid hormone receptor β (TRβ) |

Thyroid hormone Thyroid hormone |

| Vitamin D3 receptor (VDR) | Calcitriol |

| Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β (PPARβ) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) |

Fatty acids, fibrates, leukotriene B4

Fatty acids Fatty acids, thiazolidinediones |

| Pregnane X receptor (PXR) | Xenobiotics |

| Liver X receptor α (LXRα) Liver X receptor β (LXRβ) |

Oxysterols Oxysterols |

| Estrogen receptor α (ERα) Estrogen receptor β (ERβ) |

Estradiol-17, tamoxifen Estradiol-17 |

| Progesterone receptor (PR) | Progesterone, RU 486 |

| Glucocorticoid receptor (GR) | Cortisol, dexamethasone, RU 486 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) | Aldosterone, spironolactone |

| Androgen receptor (AR) | Testosterone, flutamide |

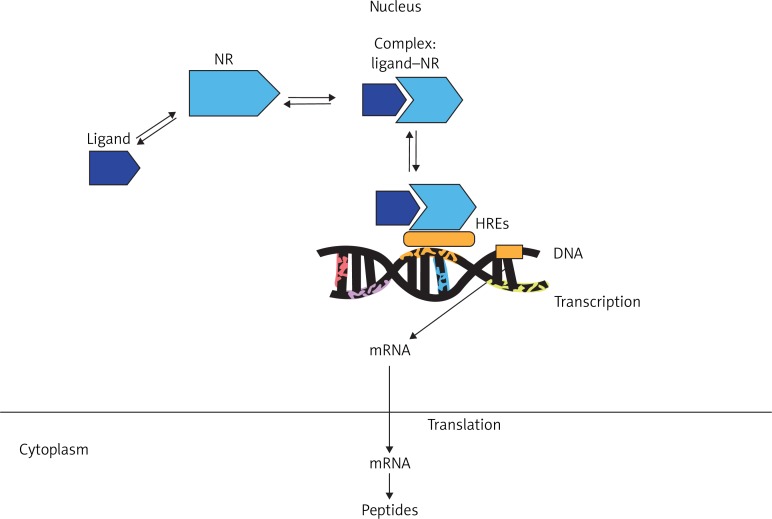

Figure 1.

Mechanism of action of nuclear receptors

Ligand (Table 3) binds to a specific nuclear receptor (NR) (RXRs, RARs, TRs, VDR, PPARs, PXR, LXRs, PR, GR, MR, AR). This causes the change of conformation of the NR. After conformational changes, a complex: ligand-NR is able to connect with a specific fragment of the DNA called “hormone response element” (HRE), activating the transcription of appropriate genes and production of the specific peptides

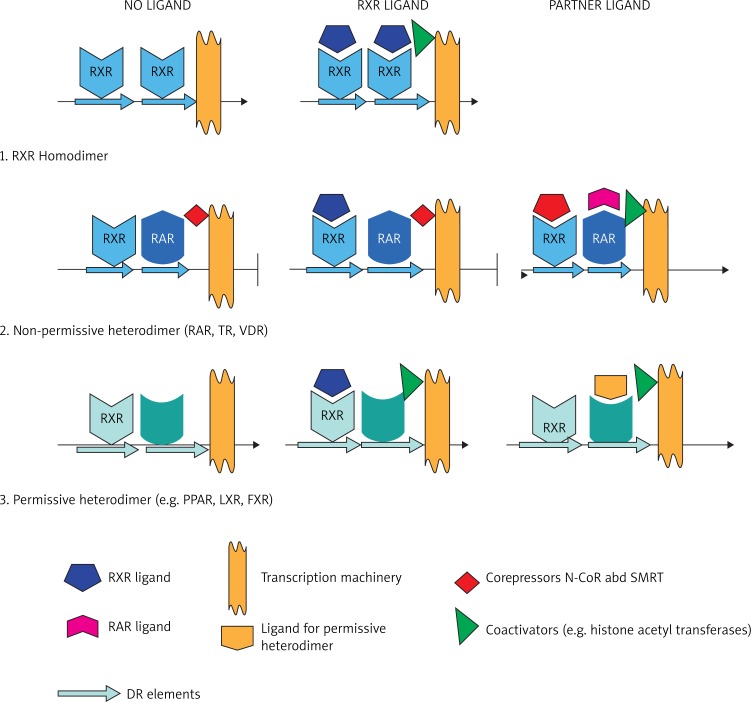

Retinoic acid receptors can homodimerize or heterodimerize with RXRs to affect differentiation and cell growth, while RXRs form three different types of dimers: RXR homodimer, permissive heterodimers and nonpermissive heterodimers [18]. Retinoic X receptor homodimers and RXR permissive heterodimers (e.g. PPAR, liver X receptor (LXR), pregnane X receptor (PXR)) are activated upon RXR ligand binding. This class of dimer formation triggers a conformational change of the RXR, that allows binding to the RXR. Nonpermissive heterodimers (e.g. RAR, VDR, TR) cannot be activated by the RXR agonists ligand alone, but only by the ligand of the partner receptor, alone or in combination with an RXR ligand [19, 20] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Retinoid receptor responses [20]

Retinoid receptor responses are predicted by the pairing partner. 1. In the absence of ligand, RXR homodimers assembled on DR elements in target gene promoters present a weak repressive activity. Retinoic X receptor ligands induce the recruitment of transcriptional coactivators (e.g. histone acetyl transferases), interaction with the transcription machinery, and activation of gene transcription. 2. Nonpermissive heterodimers: RXR/RAR (or high affinity hormone receptor) mediate repression in the absence of ligand due to interaction with transcriptional corepressors SMRT and N-CoR and associated histone deacetylases. Repression is abrogated by the interaction of the RAR ligand, but not the RXR ligand, due to the requirement for corepressor displacement mediated by ligand-induced conformational change in the RAR protein. 3. Permissive heterodimers containing an RXR molecule and a low affinity receptor (e.g. LXR, FXR, PPAR) can be activated by binding of the ligand to either receptor. Simultaneous binding by both ligands elicits synergistic activation [20]

Retinoic X receptors are expressed in almost every tissue of the body. Retinoic X receptor α has been expressed mainly in the liver, lung, muscle, kidney and intestine and, what is the most important for dermatologists, it is considered as the major subtype in the skin. Retinoic X receptor β has been expressed ubiquitously. Retinoic X receptor γ has been found in the brain and (cardiac and skeletal) muscles [21]. The endogenous RAR ligands are all-trans retinoic acid and 9-cis retinoic acid, with similar affinity, while RXRs can bind only 9-cis retinoic acid. RXR/RAR heterodimers bind to a specific DNA sequence – retinoic acid response elements (RAREs), while the RXR homodimers binds to the retinoid X response element (RXRE) [17].

Rexinoids, cell cycle and apoptosis

Rexinoids (e.g. bexarotene) are retinoid-derived synthetic compounds that exclusively bind to the RXRs. Bexarotene does not have significant RAR binding and transactivation of RAR-response genes except at higher dose levels [22].

Activation of RXR and its heterodimer partners lead to the multitargeted approach, which suggests that bexarotene may be an active agent in treatment of malignances [23]. Bexarotene modulates cell cycle progression by activating p53, by phosphorylation at Ser15, which influences the binding of p53 to promoters for cell cycle arrest, induces p73 upregulation, and also modulates some p53/p73 downstream target genes [24]. Dragnev et al. [25] reported that bexarotene represses the expression of cyclin D1, cyclin D3, total epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and phosphor-EGFR expression with dosage-dependent in non-small cell lung cancer. Furthermore, bexarotene is an inductor of apoptosis where the caspases play a crucial role. The apoptotic caspases are separated into a hierarchy of initiators (caspase-2, -8, -9 and -10) and executioners (caspase-3, -6 and -7) [26]. Once activated initiator-caspases can activate the effector-caspases, cleaving poly-(ADP-ribose)polymerase (PARP) and generate apoptosis. The cleavage of PARP is considered to be a hallmark of apoptosis for various anti tumor agents [27]. Bexarotene can cause the apoptosis of CTCL cell lines influencing the activation of caspase-3, cleavage of PARP, and down-regulation of survivin (one of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein family (IAP) suppressing the caspase activity and protecting cells from apoptosis) [28, 29].

Bexarotene also inhibits metastasis. Yen et al. had shown that bexarotene decreases migration and invasiveness of tumor cells in a dose-dependent manner [28]. In A549 cells, treatment with bexarotene resulted in reduction in matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), VEGF, EGF and increase in secretion of tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs).

Moreover, bexarotene inhibited angiogenesis. The analysis of tumor-conditioned medium indicated that bexarotene decreased the secretion of angiogenic factors and matrix metalloproteinases. The inhibitory effect of bexarotene on angiogenesis and metastases was revealed through activation of its heterodimerization partner PPARγ [30].

Rexinoids present an immunomodulatory effect. They have been shown to increase interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R) expression. Sidell et al. [31] had noticed that ATRA, a RAR-specific ligand, could upregulate the expression of IL2Rα on human thymocytes by increasing steady-state mRNA levels. Gorgun and Foss [32] had confirmed these findings investigating the effects of ATRA, bexarotene and alitretinoin (which binds both RAR and RXR) on human T-cell and B-cell leukemia cell lines. All three agents evoked upregulation of both α and β components of the IL-2R. Similar findings were observed in the same study with Sézary cells and B-cell lymphocytic leukemia cells.

As mentioned before, the RXRs form heterodimers with various other nuclear hormone receptors, which in turn act as ligand-inducing transcription regulatory factors [33, 34]. It may also work through the down-regulation of Th2 cytokines and E- selectin on endothelial cells [35, 36]. Bexarotene inhibits malignant cells trafficking to the skin through an ability to suppress CCR4 expression among malignant lymphocytes [37].

Retinoids in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas

Isotretinoin

Isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) was the first retinoid used in MF/SS. It has been effective as monotherapy in both tumor- and plaque-stage MF at doses of 1 to 3 mg/kg/day. Kessler et al. [38] had treated 25 patients with MF including 7 patients with erythroderma and 5 patients with more than 5% of Sézary cells (SC) but not diagnosed as SS, with isotretinoin 1-2 mg/kg/day. Only 3 of 25 had complete response (CR) (stage unspecified) and median response duration was greater than 8 months (1-25 months). Molin et al. [39] had used isotretinoin in 39 patients with MF/SS. Objective response to 0.2 mg/kg/day to 2 mg/kg/day was 59% including one of 5 patients with SS [39, 40]. The potential benefit of isotretinoin was reported by Leverkus et al. [41] in a more aggressive type of MF (follicular MF), especially for the treatment of residual cysts and comedones.

Etretinate and acitretin

Etretinate was primarily FDA approved for the treatment of psoriasis and was also used in several clinical trials in MF and SS before bexarotene. It has been used successfully as monotherapy. Claudy et al. [42] had treated 6 patients (5 patients with advanced MF and 1 patient with SS) with etretinate 0.8-1 mg/kg/day. Clinical response was observed in 5 of them, however without histological clearance in the skin. Etretinate was withdrawn from the market in 1998 because of its long half-life, protracted tissue storage time and prolonged risk of teratogenicity in women. It was replaced by acitretin (metabolite of etretinate) characterized by shorter half-life (49 h). Molin et al. [39] had reported clinical response in 3 of 4 patients with MF treated with acitretin but not in a patient with SS. There were no significant differences in the overall response rate (ORR) (66% vs. 59%, respectively) between patients in all stages of MF/SS treated with etretinate and acitretin.

The authors of this review have also some experience with acitretin in CTCL. 7 patients with MF (IB – III) and 2 patients with SS have been treated with acitretin in monotherapy, but the results were unsatisfactory. The combined therapy (acitretin plus PUVA) had seemed to be more effective (7 patients with advanced MF) [43].

Rexinoid in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas

Bexarotene

Bexarotene is a synthetic rexinoid that binds selectively to the retinoid X receptor (RXR) isoforms (RXRα, β and γ). Bexarotene was approved by FDA in 1999 and licensed in 2002 as 75 mg soft gelatin capsules for the treatment of the refractory advanced stage CTCL. However, it has also been shown to be an effective and safe therapeutic method in the early stage CTCL. It is eliminated through the hepatobiliary system and it appears to be metabolized to oxidative forms by the cytochrome p450 3A4 isozyme [44].

The recommended initial dose of bexarotene capsules is 300 mg/m2/day. That dose may be adjusted to 200 mg/ m2/day then to 100 mg/m2/day, or temporarily suspended, if necessitated by toxicity. When toxicity is controlled, doses may be carefully readjusted upward. If there is no tumor response after 8 weeks of treatment and if the initial dose of 300 mg/m2/day is well tolerated, the dose may be escalated to 400 mg/m2/day with careful monitoring. The topical form (gel) is also in the market but it is of a relatively little use. Bexarotene has been used both as monotherapy and combination therapy for CTCL stage IIB or higher MF [45, 46].

The results of the oral treatment were better in patients who started with a bexarotene dose of more than 300 mg/m2/day (CR – 13%) compared with 300 mg/m2/day (CR – 2%) [47]. Bexarotene was administered for up to 97 weeks in clinical trials in CTCL, but it is well known that it should be continued as long as the patient is deriving benefit. Abbott et al. [48] had presented their experience with bexarotene in a retrospective study of 66 patients with MF (40) and SS (26 patients). Forty-seven of them had suffered from the advanced stage of CTCL (IIB-IVB) and 19 patients from the early stage MF but refractory to skin-directed therapies. Bexarotene was used as a single method or combined treatment. Twenty-eight patients were started on bexarotene alone. Finally, twenty patients completed at least 1 month of monotherapy. The median starting dose was 150-300 mg/m2/day. Eight of 20 patients had tolerated 300 mg/m2/day. Among all patients who competed therapy: 2 patients (10%) had CR, 10 (50%) – OR, 6 (30%) had stable disease and progression of the diseases was observed in 2 patients (10%). Among patients with SS (9), OR was observed in 78% (7) and CR in 22% (2) of them. In a group of patients who completed the bexarotene monotherapy, the median time to progression was 11 months (3-44 months).

Promising results were also obtained by Bagot [49]. The CR was observed in 1 patient with SS who was treated with bexarotene at an initial dose of 300 mg/m2/day and the duration of response was 17 months. But there are also described several patients who did not respond to bexarotene in monotherapy [50, 51]. That is why bexarotene has been also used as combination regimens. Bouwhuis et al. [50] had used bexarotene with ECP in 3 patients with SS, who did not respond to the treatment [50]. But Tsirigotis et al. [52] achieved objective response in 2 patients with SS (2/2) treated in the same way (OR 100%) [52]. Also Ranki [53] had presented one patient with SS, who was treated with bexarotene and INF-α with quite good response (5 months of PR).

There were few patients with SS who underwent complex therapy with bexarotene, INF-γ/INF-α and PUVA/TSEB, ECP and denileukin diftitox, what had revealed that bexarotene positively regulated both p55 and p75 subunits of IL2R and enhanced the susceptibility of tumor cells to denileukin diftitox. The results were much better than those achieved with rexinoids as a single agent, what has to be considered by clinicians. Response duration was over 5 months and reached even 3 years in one patient. What can be interesting, these observations confirm the efficacy of PUVA in MF/SS also in systemic disease [54–56]. Unfortunately, there have been also several reports, mainly in SS, of rapid worsening of disease after implementation of bexarotene. The mechanism of that reaction has been still unknown [50, 57–60].

Alitretinoin

Alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid) binds both known nuclear retinoid receptor families – RAR and RXR [61]. Compared with other vitamin A derivatives such as bexarotene or acitretin, oral alitretinoin can have a more favorable safety profile regarding mucocutaneous side-effects and laboratory changes of thyroid parameters [62].

Molin and Ruzicka [63] had reported very good response after alitretinoin in a patient with SS. The dose of 30 mg/day was used as part of a combination regimen with ECP with very good skin response, normalization of leukocyte count (stable 5 months of follow-up) and reduction of lymphadenopathy in ultrasound [63].

All known studies and clinical trials concerning retinoids and rexinoids in CTCL treatment are summarized in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4.

Retinoids and rexinoids in monotherapy in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome

| Treatment | Author | No. of SS/all patients in the study | Stage | Dose | MRD | Response definition | Response rate | Type of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bexarotene | Duvic et al. [47] | 17/94 | T4 + ≥ 10% PB SC | 300 mg/m2/day | UNK | SNV | OR 24% (4/17); CR none | Phase II- III study |

| Bexarotene | Abbott et al. [48] | 9/28 | T4 + ISCL B2 criteria | 150-300 mg/m2/day initially, then 300 mg/m2/day | 9 months | SNB | OR 78% (7/9) CR 22% (2/9) | Retrospective cohort study |

| Bexarotene | Bagot [49] | 1/1 | T4 + 20% PB SC | 300 mg/m2/day | 17 months | SB | OR 100% (1/1) CR 100% (1/1) | Case report |

| Bexarotene | Bouwhuis et al. [50] | 2/6 | T4 + 1000 PB SC/mm3+ clone | 300-650 mg/day | NA | SNVB | OR none | Case report |

| Bexarotene | Ruiz de Casas et al. [51] | 1/1 | T4 + 20% PB SC | 300 mg/m2/day | NA | S | OR none | Case report |

| Acitretin | Sokolowska-Wojdylo et al. [43] | 2/9 | T4 | 30 mg/day | NG | OR none – progression | Case series | |

| Etretinate | Molin et al. [39] | 1/24 | NG | 0.2-2 mg/kg/day | NG | S | OR none | Prospective cohort study |

| Etretinate | Claudy et al. [42] | 1/6 | T4 + 1000 PB SC | 0.8-1.0 mg/kg/day | ≥ 8 months | SNB | OR 100% (1/1) CR none | Case report |

| Isotretinoin | Molin et al. [39] | 5/15 | NG | 0.2-2 mg/kg/day | NG | S | OR 20% (1/5) CR none | Prospective cohort study |

| Alitretinoin | Molin and Ruzicka [63] | 1/1 | T4 | 30 mg/day | NG | S | OR 100% (1/1) CR none? | Case series |

B – blood, B2 – high blood tumor burden per ISCL/European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORCT) classification, BM – bone marrow, CR – complete response, ISCL – International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas, MRD – median response duration, MU – million units, N – nodes, NA – not applicable, NG – not given, OR – objective response, PB – peripheral blood, S – skin, SC – Sézary cells, T4 – erythrodermic stage (mycosis fungoides or SS), UNK – unknown, V – viscera

Table 5.

Rexinoids in combination regimens in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome

| Treatment | Author | No. of SS/all patients in the study | Stage | Dose | MRD | Response definition | Response rate | Type of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bexarotene + INF-α | Ranki [53] | 1/1 | T4 + 50% PB SC | Bexarotene 250 mg/m2/day + INF-α (dose UNK) | 5 months | SB | OR 100% (1/1) CR none | Case report |

| ECP + bexarotene | Tsirigotis et al. [52] | 2/5 | T4 + 1000 PB SC/µl | ECP 2 consecutive days qwk × 1 month, qowk × 1 month, then qmo + bexarotene 300 mg/m2 | 3-5 months | SB | OR 100% (2/2) CR none | Prospective cohort study |

| ECP + bexarotene | Bouwhuis et al. [50] | 3/6 | T4 + 1000 SC/µl + clone | Bexarotene 300-650 mg/day + ECP | NA | SNVB | OR none | Case series |

| ECP + INF-α + prednisone + bexarotene | Bagazgoitia et al. [58] | 1/1 | T4 + 20% PB SC | INF-α 6 MU tiw + prednisone 20 mg/day + ECP monthly × 3 years + addition bexarotene 450 mg/day | NA | S | OR none | Case report |

| ECP + INF-γ + bexarotene + PUVA | McGinnis et al. [54] | 1/1 | T4 + 23% PB SC | INF-γ 4.2 MU SQ 4 × week + monthly ECP + bexarotene 150 mg/day + PUVA biw | MRD not reached at 6 months | SB | OR 100% (1/1) CR 100% (1/1) | Case report |

| ECP + INF-γ + bexarotene + PUVA | McGinnis et al. [54] | 1/1 | CD4/CD8 48 or ≥ 20% PB SC | Monthly ECP + INF-γ MU SQ4 × week + bexarotene 150-225 mg/day + PUVA | ≥ 16 months | SB | OR 100% (1/1) CR 100% (1/1) | Case series |

| INF-α2b + ECP + bexarotene + PUVA | McGinnis et al. [54] | 2/2 | T4 + 20% PB SC | INF-α2b 1,8-2,4 MU tiw + ECP + bexarotene 75-300 mg/day + PUVA | 5 months | SN | OR 100% (2/2) CR none | Case series |

| ECP + bexarotene + PUVA | McGinnis et al. [54] | 1/1 | T4 + 20% PB SC | Monthly ECP + bexarotene 150 mg/day + PUVA | ≥ 6 months | SB | OR 100% (1/1) CR none | Case series |

| ECP + TSEBT + INF-γ + bexarotene | McGinnis et al. [54] | 1/1 | T4 + 30% PB SC | INF-γ 40 µg SQ tiw added to ECP + bexarotene 150 mg/day post – TSEBT | ≥ 3 years | SB | OR 100% (1/1) CR 100% (1/1) | Case report |

| TSEBT + INF-α + ECP ± bexarotene | Introcaso et al. [64] | 4/4 | T4 + CD 4+/CD7–≥ 10%, CD4: CD8 ratio ≥ 6.2, CD4+/CD26– ≥ 58% | TSEBT added to regimen of INF-α + ECP ± bexarotene | NG | S | OR 100% (4/4) CR 100% (4/4) | Case series |

| ECP + alitretinoin | Molin and Ruzicka [63] | 1/1 | IIIB | ECP qowk + alitretinoin 30 mg/day | 5 + | SNB | OR 100% (1/1) CR none? | Case series3 |

Abn – abnormal, β – blood, biw – two times a week (biweekly), CR – complete response, ECP – extracorporeal photopheresis, MRD – median response duration, MTX – methotrexate, MU – million units, N – nodes, NA – not applicable, OR – objective response, PB – peripheral blood, PUVA – psoralen plus ultraviolet A, S – skin, SQ – subcutaneous, SC – Sézary cells, T4 – erythrodermic stage (mycosis fungoides or SS), tiw – three times a week, TSEBT – total skin electron beam radiation, UNK – unknown, q – every, qd – once daily, qmo – every month (once a month), qowk – every other week, qwk – every week, V – viscera

Side effects of retinoids and rexinoids

Unfortunately, there are observed different side effects during the bexarotene treatment. The most common side effects reported in the literature are hyperlipidaemia and secondary hypothyroidism [65, 66].

Hyperlipidaemia is observed in patients taking at least 300 mg/m2/day of bexarotene. The main side effect associated to the treatment with rexinoids is the increase in triglyceride levels. This elevation is due to transactivation by LXR/RXR heterodimers of SREBP-1c (Sterol Regulatory element-binding proteins), a master transcriptional regulator of genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis [67, 68]. In human hepatoma cells, rexinoids stimulate triglyceride synthesis by increasing apoC-III expression [69]. Side effects depend also on the modulation of the heterodimers with the PPARs and LXRs [70, 71].

PPARα (NR1C1) stimulates lipid metabolism downregulating or upregulating genes involved in fatty acid uptake and degradation, and also in reverse cholesterol transport. PPARγ (NR1C3) acts as a regulator of adipocyte differentiation. Together, the α and β subtypes regulate the balance between catabolism and storage of long-chain fatty acids [70].

Liver X receptor (LXR) regulates cholesterol homeostasis and determines atherosclerosis susceptibility [72]. Liver X receptor α (NR1H2) is responsible for the cholesterol metabolism in the liver, whereas LXRβ (NR1H3) activates reverse cholesterol transport from the peripheral tissues to the liver by increasing the levels of plasma HDLs [71]. A cross-talk of LXR and PPAR is established in the homeostasis of fatty acids, since LXR regulates their synthesis and PPAR controls their degradation [67]. Activation of LXR by synthetic LXR ligands results in increased hepatic lipogenesis and plasma triglyceride levels and also in increased glucose utilization and reduced glucose output by the liver, because of the induction of hepatic glucokinase and reduced expression of some hepatic gluconeogenesis genes [67]. Interestingly, permissive RXR heterodimer partners are receptors for dietary lipids that bind with low affinity, whereas nonpermissive partners correspond to high-affinity hormone receptors [21]. In conclusion, the influence of rexinoids on the metabolism of lipids, fatty acids and glucose is complex. Different heterodimers might be modulated by the same ligand to produce effects that act in opposition [67].

Hypothyroidism had occurred in 40% of patients during the clinical trials but has been observed in nearly all patients in clinical practice. Side effects require early introducing of preventative therapy and subsequent monitoring [49, 73]. Patients treated with bexarotene often present central hypothyroidism, caused by suppression of pituitary production of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and subsequent reduction in circulating thyroid hormones [74]. Animal studies have shown that pharmacologic amounts of retinoids might decrease serum levels of TSH [75]. In vitro experiments have shown that 9-cis-retinoic acid inhibits partially TSHβ promoter activity probably through the thyrotrope-restricted RXRγ isoform [74].

Those and other possible side effects of bexarotene are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Side effects of bexarotene

| Side effect | Frequency [%] |

|---|---|

| Hyperlipidaemia | 100 |

| Hypothyroidism | 40-100 |

| Leucopenia | 18[44], 17[47] |

| Asthenia | 14[44], 23[47] |

| Headache | 46[44], 42[47], 16[76] |

| Anemia | 3,6[44] |

| Abdominal and/or back pain | 14[44], 17[47] |

| Nausea and vomiting | 25[44] |

| Diarrhea | 7[44], 7[47], 33[76] |

| Pruritus | 21[44], 25[47] |

| Peripheral edema | 16[76] |

| Dry skin | 10[44] |

| Skin rash | 14[44], 17[76] |

Conclusions

The primary cutaneous lymphomas have revealed a great diversity of clinical pictures with an indolent to rapid and aggressive course. The aggravating symptoms, such as pruritus and disfiguring skin lesions, severely affect the quality of life. Dysfunction of the immunological system in late stages, resulting in infections and secondary malignancies, had been quite often intensified by too early and too “strong” therapeutic interventions with polychemotherapy a few decades ago. Consequently, most of patients died from infectious problems secondary to immunosuppressive treatment, rather than from the lymphoma itself. The clinicians must always consider that a large group of patients with primary cutaneous lymphomas are elderly and suffer from co-morbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes etc. These factors negatively influence the side effects of treatment. Because there is no curative treatment of cutaneous lymphomas, especially mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, the goal should be to achieve long-lasting remission with medicaments or procedures, which are safe and have low toxicity. For this reason, skin-directed therapy as topical corticosteroids and phototherapy as well as retinoids and rexinoids, histone deacetylase inhibitors or denileukin diftitox should always be the primary therapeutic option implemented prior to chemotherapy. Rexinoids and retinoids are the best choice in almost every stage of the disease – as monotherapy or part of combination regimens. There are no high-quality randomized clinical trials evaluating the treatment of primary cutaneous lymphomas but it seems that a higher response rate can be achieved when bexarotene is combined with other systemic treatments for CTCL. The benefits are likely to depend on the type of concomitant CTCL therapy, but no study has been adequately designed to determine the optimal combination treatment so far. Hypertriglyceridaemia and hypothyroidism are the most frequent adverse events observed during treatment, mostly limited to the laboratory abnormalities, but, anyway, leading to treatment discontinuation in a quarter of patients.

In conclusion, there are no high-quality randomized clinical trials evaluating the treatment of primary cutaneous lymphomas but the results obtained in most of studies demonstrated that oral retinoids, especially rexinoids were well tolerated and effective, achieving positive responses in nearly half the patients with CTCL, whether or not previous therapies had failed. The efficacy of bexarotene is positively correlated to the initial dose and the treatment duration and it is higher when bexarotene is combined with other systemic treatments.

References

- 1.Whittaker SJ, MacKie RM. Cutaneous lymphomas and lymphocytic infiltrates. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's textbook of dermatology. 7th edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2004. p. 54.1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RS, Pandolfino T, Guitart J, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: review and current concepts. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2908–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.15.2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamandidou E, Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Blood. 1996;88:2385–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vonderheid EC, Bernengo MG, Burg G, et al. Update on erythrodermic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: report of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas. JAAD. 2002;46:95–106. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.118538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paulli M, Berti E. Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (including rare subtypes). Current concepts. II. Haematologica. 2004;89:1372–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenerowicz D, Silny W, Dańczak-Pazdrowska A, et al. Environmental factors and allergic diseases. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19:475–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joks M, Myśliwiec K, Lewandowski K. Primary breast lymphoma a review of the literature and report of three cases. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:27–33. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2011.20600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States 1973-2002. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:854–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.7.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO- EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trautinger F, Knobler R, Willemze R, et al. EORTC consensus recommendations for the treatment of mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:1014–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zackheim HS. Cutaneous T cell lymphoma: update of treatment. Dermatology. 1999;199:102–5. doi: 10.1159/000018214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel S, Pandolfino T, Guitart J, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: review and current concept. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2908–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.15.2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diamandidou E, Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Blood. 1996;88:2385–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng AL, Su IJ, Chen CC, et al. Use of retinoic acids in the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma: a pilot study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1185–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.6.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burg G, Dummer R. Historical perspective on the use of retinoids in cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma (CTCL) Clinical Lymphoma. 2000;1(Suppl):41–4. doi: 10.3816/clm.2000.s.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner CE, Jurutka PW, Marshall PA, et al. Modeling, synthesis and biological evaluation of potential retinoid-x-receptor (RXR) selective agonists: novel analogs of 4-[1-(3,5,5,8,8-Pentamethyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2napththyl) ethynylbenzoic acid (Bexarotene) J Med Chem. 2009;8:5950–66. doi: 10.1021/jm900496b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Germain P, Staels B, Dacquet C, et al. Overview of nomenclature of nuclear receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:685–704. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fanjul A, Dawson MI, Hobbs PD, et al. A new class of retinoids with selective inhibition of AP-1 inhibits proliferation. Nature. 1994;372:107–11. doi: 10.1038/372107a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka T, De Luca LM. Therapeutic potential of “rexinoids” in cancer: prevention and treatment. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4945–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howe LR. Rexinoids and breast cancer prevention. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5983–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Germain P, Chambon P, Eichele G, et al. The pharmacology and classification of nuclear receptor superfamily. RETINOID X RECEPTORS (RXRs) Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:760–72. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boehm MF, Zhang L, Badea BA, et al. Synthesis and structure activity relationship of novel retinoid X receptor-selective retinoids. J Med Chem. 1994;37:2930–41. doi: 10.1021/jm00044a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dragnev KH, Rigas JR, Dimitrovsky E. The retinoids and cancer prevention mechanism. Oncologist. 2000;5:361–8. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nieto-Rementeria N, Perez-Yarza G, Boyano MD. Bexarotene activates the p53/p73 pathway in human cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Br J Dermatol. 2008;25:1794–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dragnev KH, Petty WJ, Shah SJ, et al. A proof-of-principle clinical trial of bexarotene in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1794–800. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reding PJ, Juliano RL. Clinging to life: cell to matrix adhesion and cell survival. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005;24:425–39. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-5134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ying SX, Seal S, Abbassi N, et al. Differential effects of bexarotene on intrinsic and extrinsic pathways in TRAIL-induced apoptosis in two myeloid leukemia cell lines. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:1003–14. doi: 10.1080/10428190701242358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang C, Hazarika P, Ni X, et al. Induction of apaptosis by bexarotene in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cells: relevance to mechanism of therapeutic action. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1234–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cesario RM, Stone J, Yen WC, et al. Differentiation and growth inhibition mediated via the RXR: PPARgamma hetrodimer in colon cancer. Cancer Lett. 2006;240:225–33. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yen WC, Prudente RY, Corpuz MR, et al. A selective retinoid X receptor agonist bexarotene (LGD 1069, targretin) inhibits angiogenesis and metastasis in solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:654–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sidell N, Cheng B, Bhatii L. Upregulation by retinoic acid of interleukin-2 receptor mRNA in human T lymphocyte. Cell Immunol. 1993;146:28–37. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1993.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorgun G, Foss F. Immunomodulatory effects of RXR rexinoids: modulation of high-affinity IL-2R expression enhances susceptibility to denileukin diffitox. Blood. 2002;100:1399–403. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Querfeld C, Nagelli LV, Rosen ST, et al. Bexarotene in the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2006;7:907–15. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.7.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boehm MF, Zhang L, Badea BA, et al. Synthesis and structure – actively relationships of novel retinoid X receptor – selective retinoids. J Med Chem. 1994;37:2930–41. doi: 10.1021/jm00044a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Budgin JB, Richardson SK, Newton SB, et al. Biological effects of bexarotene in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:315–21. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng SX, Kupper T. A new rexinoid for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:649–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richardson SK, Newton SB, Bach TL, et al. Bexarotene blunts malignant T-cell chemotaxis in Sézary syndrome: reduction of chemokine receptor 4-positive lymphocytes and decreased chemotaxis to thymus and activation-regulated chemokine. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:792–7. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kessler JF, Meyskens FL, Levine N, et al. Treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides) with 13-cis – retinoic acid. Lancet. 1983;1:1345–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molin L, Thomsen K, Volden G, et al. Oral retinoids in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a comparison of isotretinoin and etretinat: a study from the Scandinavian mycosis fungoides group. Act Derm Venereol. 1987;67:232–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomsen K, Molin L, Volden G, et al. 13-cis – retinoic acid effective in mycosis fungoides group. Act Derm Venereol. 1984;64:563–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leverkus M, Rose C, Bröcker EB, Goebeler M. Follicular cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: beneficial effect of isotretinoin for persisting cysts and comedones. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:176–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Claudy AL, Rouchouse B, Boucheron S, Le Petit JC. Treatment of cutaneous lymphoma with etretinat. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1983.tb03991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sokołowska-Wojdyło M, Maciejewska-Radomska A, Trzeciak M, Roszkiewicz J. Wyniki leczenia chorych z pierwotnymi chłoniakami skóry (CTCL) w Klinice Dermatologii Akademii Medycznej w Gdańsku w latach 1997-2008. Dermatol Klin. 2009;11:141–6. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duvic M, Martin AG, Kim Y, et al. Phase 2 and 3 clinical trial of oral bexarotene (Targretin capsules) for the treatment of refractory or persistent early – stage cutaneous T- cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:581–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Talpur R, Ward S, Apisarnthanarax N, et al. Optimizing bexarotene therapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. JAAD. 2002;47:672–84. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.124607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh F, Lebwohl MG. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma treatment using bexarotene and PUVA: a case series. JAAD. 2004;51:570–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duvic M, Hymes K, Heald P, et al. Bexarotene is effective and safe for treatment of refractory advanced – stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: multinational phase II-III trial results. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2456–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abbott RA, Whittaker SJ, Morris SL, et al. Bexarotene therapy for mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1299–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bagot M. Treatment of Sézary syndrome with bexarotene after INF alpha and methotrexatee failure. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26(Suppl):27–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bouwhuis SA, Davis MD, el-Azhary RA, et al. Bexarotene treatment of late-stage mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome development of extracutaneous lymphoma in 6 patients. JAAD. 2005;52:991–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruiz de Casas A, Carrizosa-Esquivel A, Herrera-Saval A, et al. Sézary syndrome associated with granulomatous lesions during treatment with bexarotene. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:372–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsirigotis P, Pappa V, Papageorgiou S, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis in combination with bexarotene in the treatment of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:1379–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ranki A. Bexarotene combination therapy for patients with Sézary syndrome. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26(Suppl):55–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McGinnis KS, Shapiro M, Vittorio CC, et al. Psoralen plus long-wave UV-A (PUVA) and bexarotene therapy: an effective and synergistic combined adjunct to therapy for patients with advanced cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:771–5. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foss F, Demierre MF, DiVenuti G. A phase-I trial of bexarotene and denileukin diftitox in patients with relapsed or refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2005;106:454–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DiVenuti GM, Foss FM. Phase I dose escalation study of Targretin and Ontak in hematologic malignancies: upregulation of IL2R expression by low dose targretin. Blood. 2001;98:601a. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sokołowska-Wojdyło M, Roszkiewicz J, Zaucha JM, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic problems in a case of mycosis fungoides diagnosed first as actinic reticuloid. Przegl Dermatol. 2010;97:196–202. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bagazgoitia L, Perez-Carmona L, Rios L, et al. Acute hyperkeratotic and desquamative reaction in a patient with Sézary syndrome treated with bexarotene. JEADV. 2008;22:389–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGinnis KS, Ubriani R, Newton S, et al. The addition of interferon gamma to oral bexarotene therapy with photopheresis for Sézary syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1176–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.9.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruiz de Casas A, Carrizosa-Esquivel A, Herrera-Saval A, et al. Sézary syndrome associated with granulomatous lesions during treatment with bexarotene. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:372–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheng C, Michaels J, Scheinfeld N. Alitretinoin: a comprehensive review. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:437–43. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ruzicka T, Larsen FG, Galewicz D, et al. Oral alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid) therapy for chronic hand dermatitis in patients refractory to standard therapy: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, multicenter trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1453–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.12.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Molin S, Ruzicka T. Possible benefit of oral alitretinoin in T-lymphoproliferative diseases: a report of two patients with palmoplantar hyperkeratotic-rhagadiform skin changes and mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1399–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Introcaso CE, Micaily B, Richardson SK, et al. Total skin electron beam therapy may be associated with improvement of peripheral blood disease in Sézary syndrome. JAAD. 2008;58:592–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith BD, Wilson LD. Management of mycosis fungoides. Treatment: part 2. Oncology. 2003;17:1419–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Whittaker SJ, Marsden JR, Spittle M, et al. Joint British Association of Dermatologists and UK Cutaneous Lymphoma Group guidelines for the management of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:1095–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Perez E, Bourguet W, Gronemeyer H, et al. Modulation of RXR function through ligand design. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;4:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schultz JR, Tu H, Luk A, et al. Role of LXRs in control of lipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2831–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.850400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vu-Dac N, Gervois P, Torra IP, et al. Retinoids increase human apo C-III expression at the transcriptional level via the rexinoid X receptor. Contribution to the hypertriglyceridemic action of retinoids. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:625–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Michalik L, Auwerx J, Berger JP, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LXI. Peroxisome profiferator-activated receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:726–41. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moore DD, Kato S, Xie W, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LXII. The NR1H and NR1I receptors: constitutive androstane receptor, pregnane X receptor, farnesoid X receptor alpha, farnesoid X receptor beta, and vitamin D receptor. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:742–59. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chawla A, Repa YJ, Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear receptors and lipid physiology: opening the X-files. Science. 2001;194:1866–70. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Olsen EA, Rook AH, Zic J, et al. Sézary syndrome: Immunopathogenesis, literature review of therapeutic options, and recommendations for therapy by United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium (USCLC) JAAD. 2011;64:352–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sherman SI. Etiology, diagnosis and treatment recommendations for Central Hypothyroidism Associated with Bexarotene Therapy for Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma. 2003;3:249–52. doi: 10.3816/clm.2003.n.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Coya R, Carro E, Mallo F, et al. Retinoic acid inhibits in vivo thyroid-stimulating hormone secretion. Life Sci. 1997;60:247–50. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prince HM, McCormack C, Ryan G, et al. Bexarotene capsules and gel for previously treated patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: results of the Australian patients treated on phase II trials. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:91–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2001.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]