Abstract

Introduction

A prolonged feeling of shame leads to particularly negative consequences and it accompanies, as well as triggers, any kind of stigma.

Aim

As empirical works on shame due to stigmatizing diseases are scarce, the authors aimed to investigate the following: 1) which diseases are perceived as the most embarrassing, and 2) what level of shame is attributed to the embarrassing diseases by affected patients. Additionally, the authors assumed that the differentiation variable for the second aim would be the level of infectiousness (or non-infectiousness) of a given disease.

Material and methods

A two-stage study was carried out in 2011–2013. Three groups of patients affected by various diseases were included into the actual study: 1) people suffering from non-infectious (42 psoriasis and 42 acne subjects) and 2) infectious (25 syphilis cases) diseases. The patients filled in an original questionnaire, designed especially for the purpose of the study.

Results

As the most shameful acne patients consider syphilis, but patients with syphilis – AIDS. Patients with syphilis assigned to their disease the greatest shame (average 75%), and the lowest – acne patients (average 30%). Patients with psoriasis assessed on 52% shame experienced because of the disease.

Conclusions

The conducted study confirmed the accuracy of the empirical assumptions which may be applicable in prevention as well as therapy of negative consequences of shame.

Keywords: shame, embarrassing illnesses, psoriasis, acne, syphilis

Introduction

The multidimensional feeling of shame may have a powerful – either positive or negative – influence on the development of individuals and their social functioning [1–10]. The positive impact of shame consists in a socially sanctioned right to bodily integrity and privacy and allows individuals to form their personal and social identity [2, 8]. However, shame more often has a negative function as it triggers the remorse, inseparably connected with experiencing the feelings of guilt and personal inferiority. Shame appears as a consequence of negative evaluation, either internal or external, of one’s actions in relation to behavior and social norms. The experience of shame acutely lowers the feeling of self-esteem, resulting in one’s perception of self as a bad, unworthy and worthless person [1–4, 6, 7, 11–16]. Shame is accompanied by the following psychical symptoms: fear, anxiety, psychical suffering, loss of self-confidence, lowered self-esteem, anger, and frustration. In turn, they lead to various forms of psychopathologies, especially social phobias and depression, obsessive-compulsive and eating disorders, risky behaviors and all sorts of addictions [2, 3, 6, 7, 14, 17].

A prolonged feeling of shame has particularly negative consequences. It accompanies, as well as triggers, any kind of stigma as the same discriminating attributes (among others appearance, nationality, religion, origin, personal features, disability, sexual orientation, state of health) lie at its source [5, 9].

Certain illnesses connected with negatively perceived etiology, localization, symptoms and the possibility of infecting others, belong to a group of particularly stigmatizing, causing social fear and shameful diseases [18–20]. Almost all chronic diseases, located in the private parts of the human body, sexually transmitted and affecting the skin, with deforming, visible and repulsive skin lesions, fall under that category [21, 22]. In many cases their origin is linked with failure to maintain hygienic norms, unhealthy or pro-miscuous lifestyle, or risky and irresponsible sexual behaviors.

Aim

As empirical works on shame related to stigmatizing diseases are scarce [23], the study aimed to investigate the following: 1) which diseases are perceived as the most embarrassing, and 2) what level of shame is attributed to embarrassing diseases by affected individuals. Additionally, the authors assumed that the differentiation variable for the second aim would be the level of infectiousness (or non-infectiousness) of a particular disease.

Material and methods

A two-stage study was carried out in 2011–2013. First, a set of 35 most embarrassing illnesses was designed with the help of various physicians. After the preliminary study in a group of 314 people, a list of 10 diseases was evaluated by 219 people on a scale from 1 to 10 (from the lowest to the highest level of shame). Three groups of patients affected by various diseases from that list (109 patients), treated at the Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, between September 2012 and March 2013, were included into the actual study. The study group comprised people suffering from non-infectious (42 psoriasis and 42 acne subjects) and infectious (25 syphilis cases) diseases.

Patients filled in an original questionnaire, designed especially for the purpose of the study, consisting of 9 half-open tasks created on the basis of medical and psychotherapeutic experiences of the investigating team. The article includes the answers of the respondents.

Statistical analysis

The χ2 test, Kruskal-Wallis test and multiple comparison test were used for the statistical analysis, with p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

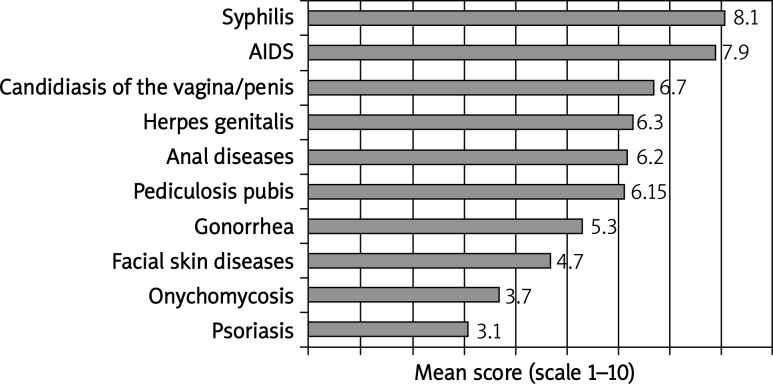

The final classification of diseases evaluated by 533 people as the most embarrassing is presented below (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

The list of 10 most embarrassing diseases

First, acne, psoriasis and syphilis patients categorized the 10 diseases according to the level of shame associated with them, using a scale from 1 (the lowest) to 10 (the highest). Acne patients found syphilis to be the most embarrassing condition (mean = 7.6), while syphilis and psoriasis patients pointed to AIDS (9.0 and 7.9, respectively). Anal diseases were selected by the former (mean = 6.6), and syphilis by the latter (7.5 and 7.7, respectively) as the second most embarrassing illness.

Next, the respondents decided what level of shame, expressed as a percentage, corresponded to their own disease in comparison to the disease considered to be the most (100%) embarrassing.

Syphilis and acne patients perceived their own illnesses as the most and the least embarrassing (approx. 75% and 30%), respectively. Psoriasis patients assigned the score of 52% to their own condition. The results are presented in the table (Table 1). A statistically significant difference between the levels of shame was detected between the groups (Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0001). A multiple comparison test revealed that the differences were present in all compared groups, i.e. 1) syphilis vs. acne (p = 0.0001); 2) syphilis vs. psoriasis (p = 0.02); 3) acne vs. psoriasis (p = 0.0135).

Table 1.

Type of the disease and level of shame

| Perception of shame (%) Group | N | Mean | Min. | Max. | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syphilis | 25 | 75 | 30 | 100 | 23 |

| Acne | 42 | 30 | 1 | 100 | 26 |

| Psoriasis | 42 | 52 | 0 | 100 | 35 |

Source: authors’ own experience

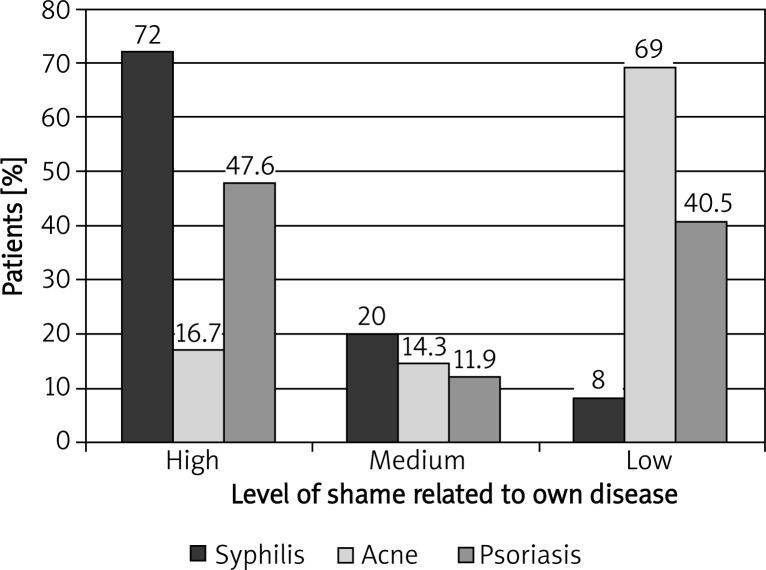

Detailed analysis of the obtained results showed considerable patient diversity regarding the level of shame associated with their own disease. A high level of shame was most frequently correlated with syphilis. The majority of acne subjects selected low-level shame scores for their own disease, while results for psoriasis patients were almost equally high or low. In the majority of cases, a medium level of shame was assigned to syphilis, rather than acne and psoriasis, by the affected subjects (Figure 2). The correlation between the level of experienced shame and type of disease proved to be statistically significant for both extreme levels, i.e. low (χ2, p = 0.0001) and high (χ2, p = 0.01). Moreover, the difference between the levels of shame attributed to non-infectious (acne, psoriasis) and infectious (syphilis) diseases turned out to be statistically significant (χ2, p = 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Level of shame related to own disease in the studied population

Discussion

Syphilis, diseases of the facial skin and psoriasis were included in the first 10 most embarrassing conditions according to 533 Polish respondents. The list differed from the international compilation of 10 most stigmatizing diseases as out of the illnesses of the studied patients only psoriasis can be found on the international list [24]. The differences might stem from the methodology of designing the list, social and historical knowledge about stigmatizing diseases, as well as their incidence in a given area.

Almost all differences in experiencing shame by acne, psoriasis and syphilis patients (with the exception of the medium level of shame) due to their own disease proved to be statistically significant. The lowest (approx. 30%) level of shame was noted in acne subjects, who also described their level of shame as low (69%) when compared to syphilis (100%). That result is favorable for acne patients because it proves they are aware of the fact that they need not experience embarrassment about their own disease when compared to syphilis, associated with the highest level of shame. That finding supports the efficiency of the technique known as downward social comparison [25], which may be used by physicians and therapists in the treatment of acne patients. Also, it proves that affected patients perceive the common social belief that acne is not permanent and non-infectious as correct. Patients who evaluated the level of experienced shame as medium (14.3%) or high (16.7%) have most probably been subjected to various forms of ostracism and discrimination due to visible symptoms of their disease. They also could have been accused of maintaining insufficient hygiene or leading unhealthy lifestyle [26].

Psoriasis patients experienced medium (approx. 52%) shame due to their disease. They evaluated their embarrassment as high (47.6%) or low (40.5%) in comparison to AIDS, which in their eyes was associated with a 100% feeling of shame. A high level of shame attributed to psoriasis ought to be connected with inadequate social knowledge about non-infectious nature of the disease. As a result, affected individuals become targets of stigma as visible lesions typical of psoriasis may evoke negative reactions and fear of being infected in non-affected populations [27, 28]. Possibly, in the case of patients who attributed a low level of shame to their condition, skin lesions are easily camouflaged and/or the knowledge about psoriasis and understanding of the problems of affected individuals are better.

The highest level of embarrassment due to their own disease (approx. 75%) was reported by syphilis patients. The comparison between the level of the experienced shame to the 100% reference point (AIDS) allowed 72% of the syphilis patients to award a high score to the negative emotion they experienced. Distinct and statistically significant advantage of the high level of shame experienced by syphilis patients is in agreement with the highest position syphilis occupies on the list of the most embarrassing conditions (mean score = 8.1 on a 1–10 scale). These findings may evoke a high level of concern. In the case of syphilis, shame may function as a defense mechanism against stigma and ostracism, and as an obstacle to reveal the truth, even in a very close relationship. Syphilis patients may deny their condition and, in that way, fulfill a proper social role, i.e. of a person without the stigma of a sexually transmitted disease [9]. The consequences of that role – based on withholding or conveying misleading information – are risky and socially threatening [29–34]. Studies carried out in China, where syphilis incidence increases by 30% annually, offer the largest body of data and evidence on the topic. For example, although 80% out of 406 affected men felt stigmatized by their disease, 77% declared their unwillingness to inform their partners about the possibility of disease transmission and infection, while 40% had a sexual intercourse with full awareness of the risk of infecting the partner [35].

The aim of the study was to determine and verify differences in the level of shame attributed to their own disease by patients suffering from illnesses from the list of 10 most embarrassing conditions. Syphilis, both on the list and in the perception of patients, stands out as the most embarrassing disease.

Syphilis-induced shame turned out to be statistically significant in comparison to shame experienced by acne and psoriasis patients. Moreover, comparing shame induced by one’s own disease to the 100% reference point, i.e. AIDS, allowed most syphilis patients to give a high score to the negative emotion they experienced.

The empirical findings may be useful in prevention and therapy of shame, as well as its pathological consequences, connected not only with the lives of syphilis patients, but also with the majority of interpersonal contacts, particularly the ‘physician/psychotherapist-patient’ relation.

References

- 1.Kurtz E. Shame and guilt. Warsaw: Instytut Psychologii Zdrowia i Trzeźwości; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufman G. The psychology of shame: theory and treatment of shame-based syndromes. New York: Springer; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis M. Shame. The exposed self. New York: Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradshaw J. Healing the shame that binds you. Warszawa: Akuracik; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leary M. Self-presentation. Gdańsk: Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller RS. Embarrassment: Poise and peril in everyday life. Gdańsk: Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tangney JP, Dearing RL. Shame and guilt (emotions and social behavior) New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erikson EH. Identity and the life cycle. Poznań: Zysk i Spółka; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goffman E. Stigma. Gdańsk: Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dryden W. Overcoming shame. Łódź: Wydawnictwo JK; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makara-Studzińska M, Sygit K, Sygit M, et al. Analysis of the phenomenon of attempted suicides in 1978-2010 in Poland, with particular emphasis on rural areas of Lublin Province. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19:762–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mojs E, Warchoł-Biedermann K, Głowacka MD, et al. Are students prone to depression and suicidal thoughts? Assessment of the risk of depression in university students from rural and urban areas. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19:770–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deblinger E, Runyon MK. Understanding and treating feelings of shame in children who have experienced maltreatment. Child Maltreat. 2005;10:364–76. doi: 10.1177/1077559505279306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stuewig J, McCloskey LA. The relation of child maltreatment to shame and guilt among adolescents: psychological routes to depression and delinquency. Child Maltreat. 2005;10:324–36. doi: 10.1177/1077559505279308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Attachment. 2010. http://www.attachmentdisordermaryland.com/shame+attachment.htm, (9.03.2013).

- 16.Hayes Grieco M. 2012. http://innerself.com/content/self-help/behavior-modification/attitudes-transformed/perfectionism/7894-about-unhealthy-self-destructive-shame.html, (15.03.2013).

- 17.Zayfert C, DeViva JC, Hofmann SG. Co-morbid PTSD and social phobia in a treatment-seeking population: an exploratory study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193:93–101. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000152795.47479.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jakubowicz O, Żaba R, Czarnecka-Operacz M. Serological tests for syphilis performed in the Sexually Transmitted Diseases Diagnostic Laboratory in Poznań during 2000-2004. Postep Derm Alergol. 2011;28:30–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saylor C, Yoder M, Mann RJ. Stigma. In: Lubkin IM, Larsen PD, editors. Chronic illness: impact and interventions. Boston: Jones & Bartlett; 2002. pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rzepa T, Jakubowicz O, Skopińska S, Żaba R. Shameful disease and sexual orientation – preliminary study. Probl Hig Epidemiol. 2012;3:519–24. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talasiewicz K, Ołdakowska A, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A. Evaluation of knowledge about acne vulgaris among a selected population of adolescents of Tricity schools. Postep Derm Alergol. 2012;29:417–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graczyk A, Malec J, Miniszewska J, Zalewska-Janowska A. Psychological aspects of atopic dermatitis and contact dermatitis: stress coping strategies and stigmatization. Postep Derm Alergol. 2012;29:14–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller M. Shame and psychotherapy. 2006. http://www.columbiapsych.com/shame_miller.html, (14.03.2013).

- 24.Pappas S. Top 10 stigmatized health disorders. 2011. http://www.livescience.com/14424-top-10-stigmatized-health-disorders.html, (5.04.2013).

- 25.Aronson E, Wilson TD, Akert RM. Social psychology. Poznań: The heart and the mind. Zysk i Spółka; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunliffe W. Teenagers with acne cite shame, embarrassment about condition of skin. 2004. http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Teenagers+with+acne+cite+shame,+embarrassment+about+condition+of+skin.-a0114129448”>, (6.04.2013).

- 27.Hawro T, Janusz I, Zalewska A, Miniszewska J. Quality of life and stigma and the severity of skin lesions and pruritus in patients with psoriasis. In: Rzepa T, Szepietowski J, Żaba R, editors. Psychological and medical aspects of skin diseases. Wrocław: Cornetis; 2011. pp. 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sampogna F, Tabolli S, Abeni D. Living with psoriasis: prevalence of shame, anger, worry, and problems in daily activities and social life. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:299–303. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JD, Craft EA. Protecting one’s self from a stigmatized disease… Once one has it. Deviant Behavior. 2002;23:267–99. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lieber E, Li L, Wu Z, et al. HIV/STD stigmatization fears as health-seeking barriers in China. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:463–71. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9047-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeynes C, Chung MC, Challenor R. Shame on you’ – the psychosocial impact of genital warts. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;8:557–60. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rzepa T, Żaba R. Coping with the stressful sigma of sexually transmitted disease. Post Psych Neurol. 2009;18:143–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rzepa T, Żaba R, Jakubowicz O, Szramka-Pawlak B. Syphilis and its consequences as a public health problem forgotten. Polityka Społeczna. 2012;3:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rzepa T, Żaba R, Jakubowicz O, Szramka-Pawlak B. Self-image and consciousness of the disease stigma. Opuscula Sociologica. 2012;22:105–16. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H, Detels R, Li X, et al. Stigma, delayed treatment, and spousal notification among male patients with sexually transmitted disease in China. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:335–43. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200206000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]