Abstract

Introduction

C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), which is one of its most important simulators, were determined in great amounts in the sera of patients with chronic urticaria (CU).

Aim

To determine the levels of IL-6 in patients with urticaria, and evaluate its relationship with urticaria activity scores and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).

Material and methods

Fifty-three patients with CU were included in the study successively by determining their urticaria activity scores (0-3) and DLQI (0-5). The CRP and IL-6 were measured by immune assay methods. Thirty-two healthy subjects were included as a control group.

Results

Serum levels of IL-6 and CRP were significantly higher in patients with CU compared to healthy controls (p < 0.001, p = 0.026 respectively). There was a statistically significant correlation among urticaria activity scores and IL-6 and CRP concentration (p = 0.004, p = 0.042). This correlation was more significant in patients who had moderate and severe disease activity scores than in those who had mild disease activity score (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, respectively). There was a statistically significant association between DLQI and IL-6 (p = 0.025). This correlation was very significant in patients who had severe and very severe disease activity scores (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, respectively). DLQI scores and serum levels of IL-6 were significantly different in the very severe group compared to healthy controls (p = 0.024).

Conclusions

The levels of CRP and IL-6 are increased in patients with CU. A relationship of DLQI and urticaria activity scores with CRP and IL-6 was found. These findings support the relationship between the inflammatory process in CU and the clinical findings.

Keywords: chronic urticaria, Dermatology Life Quality Index, interleukin-6

Introduction

The major pathophysiological phenomena secondary to tissue damage and inflammation results in an increase in the concentrations of acute phase reactants (APR) [1, 2]. Although the name APR contains the term acute, it presents with both acute and chronic inflammatory conditions [3]. Differences in grades of APR largely stem from the effects of inflammatory molecules, called cytokines. Some of the major cytokines relevant to the APR are interleukin-6 and 1β (IL-6, IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interferon-γ (IFN-γ). These proteins influence APR production in hepatocytes, with IL-6 being the great inducer of most APR [4, 5]. Although local CRP synthesis and secretion are present in other regions, plasma CRP production is only performed by hepatocytes and this largely occurs under the transcriptional control of IL-6 [3]. In a study of Kasperska-Zajac et al., it was found that IL-6 and CRP levels were highly correlated with urticarial activity among urticaria patients and in the remission periods the level of this cytokine was low [6]. This result made us think that an increase in CRP and IL-6 must be considered as a marker of urticarial activity. It appears that dysfunction of the neuro-endocrine-immune system resulting from stress and other factors seems to be an interesting theory underlying the pathogenesis of urticaria [7]. Mast cells may be speculated to be the main source of IL-6 during chronic urticaria (CU) exacerbation associated with stress [8]. Despite an abundance of studies on pharmacology and treatment of chronic urticaria, there are only a restricted number of studies covering the quality of life of patients with CU [9, 10]. In this study we aimed to show the relationship of plasma IL-6 and serum CRP levels with disease activity and to evaluate the relationship of Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores with these parameters and disease severity.

Material and methods

Patients

Fifty CU patients (19 males and 31 females; median age 35 years, range 18-55) were included in the study. The control group consisted of 33 healthy subjects, median age is 36 years ranging from 20 to 60. Patients with CU were divided into two subgroups according to the results of the autologous skin serum test (ASST). This test was performed in accordance with the method by Sabroe et al. [11].

Negative ASST was found in 38 patients and 12 patients had a positive reaction. All the controls responded negatively to ASST. Thirty-eight patients had no history of angioedema; however, 12 had a history of angioedema. In all cases, any known causes of CU were ruled out by appropriate investigations. When blood samples were collected, no patients had any medical history of past or active infectious disease. Those with physical urticaria were excluded from the study. The administration of anti-histaminic drugs was interrupted about 1 week before the study. None of the patients included in the study had a drug administration history until 6 weeks to the study. The study was approved by the university's ethical committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Evaluation of urticaria activity scores

All patients had active disease at the time of evaluation and were divided into subgroups according to their urticarial activity. Urticaria activity score (UAS) was calculated according to EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF guidelines [12] and as described by Maurer group [13]. The UAS was estimated according to the number of wheals and pruritus intensity, on the day of blood sampling, applying the following scheme: no wheals = 0, 1-10 wheals = 1, 11-50 wheals = 2, 50 wheals = 3 and pruritus intensity: no = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2, severe = 3. UAS scores: daily (minimum = 0; maximum = 6). The UAS was classified as follows: 0-2 (mild), 3-4 (moderate) and 5-6 (severe). In our study, 13 patients had mild, 19 patients – moderate, and 18 patients – severe chronic urticaria symptoms.

Blood sampling and interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein assay

Between 8:00 and 10:00 a.m. the blood of all patients was taken and stored at –80°C until they were studied. Serum samples were gradually brought to room temperature. Plasma IL-6 concentration was determined by ELISA using (DYNEX Technologies, USA) a commercial kit (Invitrogen Corporation, 542 Flynn Road, Camarillo). Serum concentration of CRP was evaluated using the high sensitive immunochemistry system, nephelometric method (image 800, Beckman Coulter, USA).

Assay of Dermatology Life Quality Index

All patients with CU were asked to complete the DLQI at the first interview. There are 10 items in the DLQI in six subsections: Symptoms and Feelings (items 1 and 2), Daily Activities (items 3 and 4), Leisure (items 5 and 6), Work and School (item 7), Personal Relationships (items 8 and 9) and Treatment (item 10). The questions in the form were replied as “not at all”, “a little”, “a lot” and “very much”, with scores of 0, 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Depending on the patients’ responses, the total score varied between a minimum and maximum of 0 to 30. Those with a quality of life being unaffected according to the DLQI score were grouped as (0-1), mild impairment (2-5), moderate impairment (6-10), severe impairment (11-20) and very severe impairment (21-30). The highest score showed the highest impact on the quality of life [14]. We used the official Turkish version downloaded from www.dermatology.org.uk. Our study comprised 0 patients with no impairment, 5 patients with mild impairment, 10 patients with moderate impairment, 26 patients with severe impairment, and 9 patients with very severe impairment.

Statistical analysis

Data were delivered as medians and ranges, and comparisons between groups were performed by Mann-Whitney U test. The Kruskal-Wallis variance analysis was used for screening differences between the groups. The correlation was analysed by the Spearman test. Values of p below 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

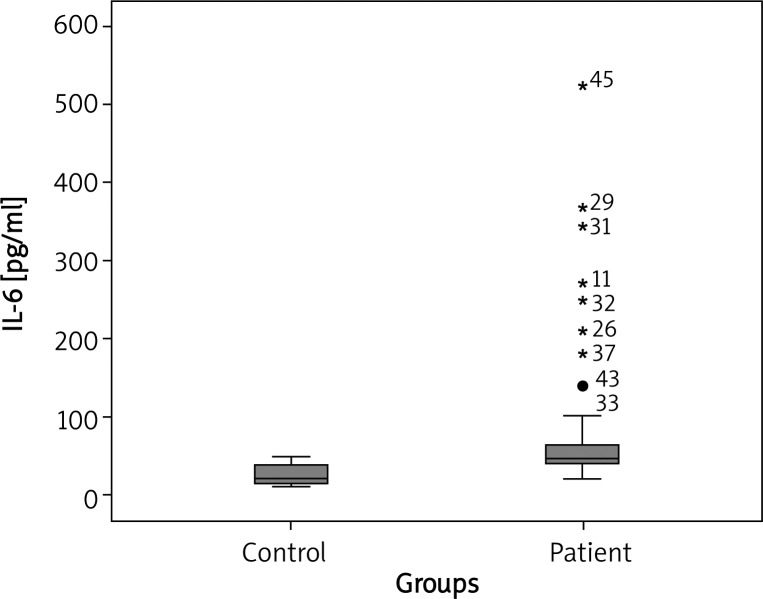

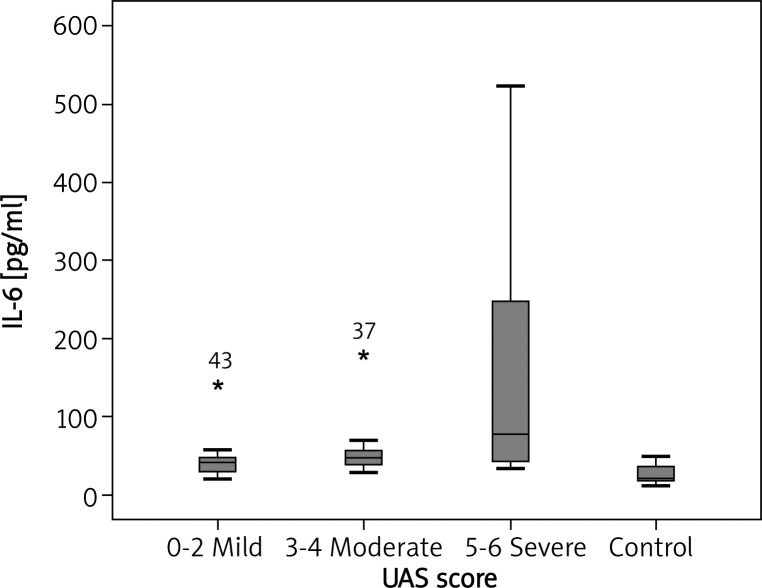

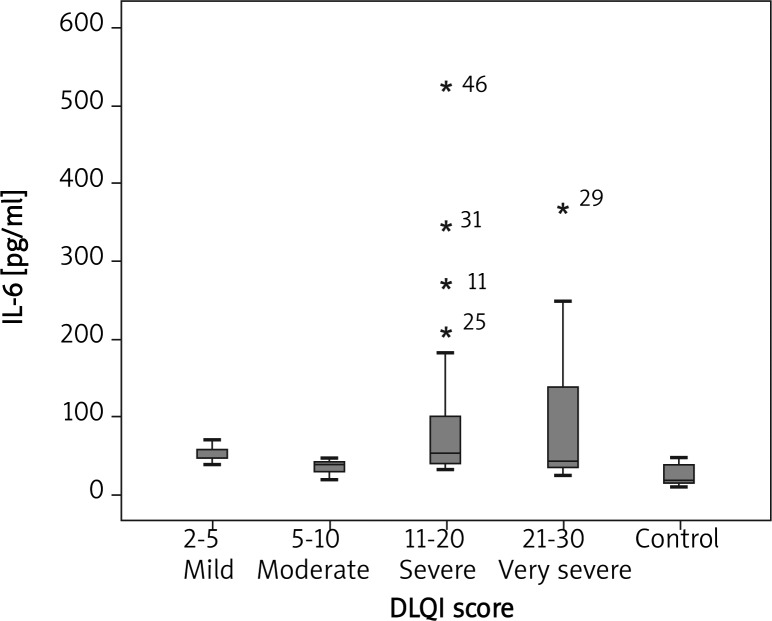

In comparison with the healthy controls in our trial, the median plasma IL-6 concentration was notably higher in CU patients (46.57 pg/ml vs. 20.34 pg/ml; p < 0.001) (Figure 1). There was a statistically significant association between UAS and IL-6 concentration (p = 0.004). Median plasma IL-6 concentrations of CU patients with mild, moderate, and severe symptoms were 39.45, 46.70 and 77.20 pg/ml, respectively (Figure 2). There was a statistically significant association between mild, moderate and severe UAS and IL-6 levels (p < 0.05, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 2). There was a statistically significant association between DLQI scores and IL-6 levels (p = 0.025). There was a statistically significant association between mild, moderate, severe, very severe DLQI scores and IL-6 levels and control group (p = 0.002, p = 0.02, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 3). There was no significant difference in median IL-6 levels (42.71, 46.65 pg/ml) between ASST(+) and ASST(–) CU patients (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Individual plasma IL-6 concentration in healthy subjects and CU patients. Boxes represent median value

Fig. 2.

Plasma IL-6 concentration in healthy subjects and CU patients with different disease activity. p = 0.004, p < 0.001, p < 0.001 for mild, moderate and severe groups, compared to the control group

Fig. 3.

DLQI score with IL-6 levels in mild, moderate, severe and very severe groups and the control group (p = 0.002, p = 0.02, p < 0.001, p < 0.001, respectively)

Table 1.

Serum concentration CRP and plasma IL-6 levels in CU patients divided according to the results of ASST

| Patient category | IL-6 [pg/ml] Median (range) | CRP [mg/dl] Median (range) | Value of p |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASST positive (n = 12) | 42.71 (31.40-406) | 0.358 (0.02-1.41) | 0.892 |

| ASST negative (n = 38) | 46.65 (4.02-50.93) | 0.298 (0.02-8.04) | 0.982 |

n – number of subjects, ASST – autologous serum skin test, CRP – C-reactive protein assay, IL-6 – interleukin-6

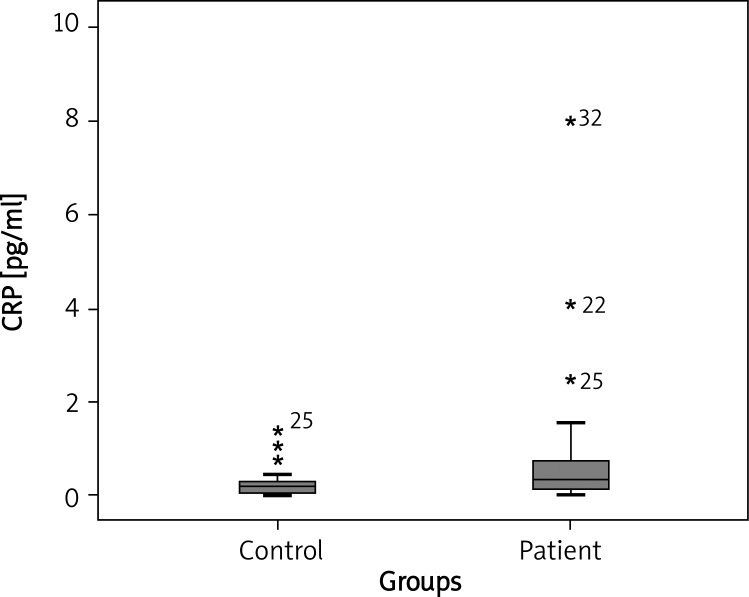

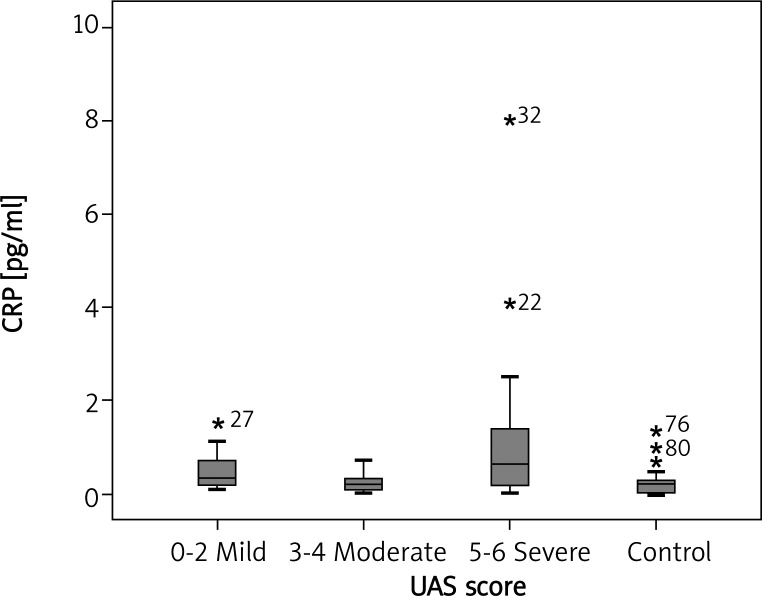

Median CRP concentrations were meaningfully higher in patients with CU compared with healthy controls (0.309 mg/dl vs. 0.158 mg/dl respectively, p = 0.026) (Figure 4). There was a statistically significant association between UAS and serum CRP concentrations (p = 0.042). Median serum CRP concentrations in patients with mild, moderate, and severe symptoms were 0.331, 0.216 and 0.641 pg/ml, respectively; p < 0.05, p > 0.05 and p < 0.05, respectively) (Figure 5).

Fig. 4.

Individual serum CRP concentration in healthy subjects and chronic urticaria (CU) patients. Boxes represent median values (0.309 pg/ml vs. 0.158 pg/ml respectively, p = 0.026)

Fig. 5.

Serum CRP concentration in CU patients with mild, moderate, and severe symptoms (median: 0.331, 0.216, 0.641 pg/ml, respectively; p < 0.05, p > 0.05, p < 0.05, respectively)

Median serum CRP concentrations in patients with mild, moderate, severe and very severe DLQI were 0.216, 0.392, 0.213 and 0.568 mg/dl respectively. There was no statistically association between DLQI scores and CRP levels (p = 0.492). There was no difference between mild, moderate and severe groups and control group with respect to DLQI scores (p = 0.589, p = 0.111, p = 0.314, respectively). There was only statistically meaningful difference between the severe group and control group (p = 0.024). There was no significant differences in median CRP levels between ASST(+) and ASST(–) CU patients (0.358, 0.298 mg/dl; p > 0.05) (Table 1). The UAS and DLQI were not meaningful with regard to history of angioedema (p = 0.089, p = 0.911). No significant correlation was detected between circulating concentration of IL-6 and CRP (r = –0.167, p > 0.05) in CU patients.

Discussion

The important role of mast cells in CU occurrence was proven in previous studies [15]. It has been acknowledged that tryptase-positive, chymase-negative mast cells might serve as an important source of IL-6 in CU [16]. The IL-6 is a cytokine involved in chronic stress states [17, 18]. It is known that the increasing secretions of IL-6 occur during various immune-inflammatory processes including hypersensitivity reactions and autoimmune diseases [18–20]. The IL-6 is an inducer of many acute phase proteins such as the CRP, which controls the level of local and systemic inflammatory responses [5, 21].

The CRP is a strong activator of the classical complement cascade and may start or exacerbate inflammatory lesions in this manner under certain conditions [22, 23].

Many studies on inflammatory conditions have demonstrated that although not in all diseases, in most cases the CRP concentration was also parallel to the activity of the disease such as IL-6 concentration. It is not clear whether or not this increase in IL-6 and CRP is only an epiphenomenon or has contributed to the pathogenesis of CU [8].

Plasma IL-6 and serum CRP concentrations were recently investigated and IL-6 levels were found to be increased in patients with urticaria. The meaningful relationship with the disease activity score was only determined by Kasperska-Zajac et al. but was not referred to in the study of Dos Santos [6, 24, 25]. In comparison with the healthy controls in our trial, plasma IL-6 concentration was notably higher in CU patients. Similar to the literature, there was an important correlation between the UAS and IL-6 concentration.

Kasperska-Zajac et al. have shown that the increased IL-6 plasma levels was a reversible phenomenon and have shown that it increased in active disease periods and decreased in remission [6]. The limitation of this study is that IL-6 levels of the patients during remission (either spontaneously or drug-induced) were not measured. It has been suggested that mast cells may play a central role in disease syndromes with a neural, immune and endocrine component exacerbated under stress [26]. It has been demonstrated that IL-6 is secreted upon psychological stress, depression and other negative emotions [17, 27]. Because it is known that IL-6 levels increase with stress, it cannot be determined whether this increase is due to disease activity or emotions [8]. Symptoms of urticaria including pruritus and distressing lesions present as the source of physical and psychological distress [28, 29]. Baiardini et al. reported a severe impairment of quality of life in CU patients [30]. The DLQI and Skindex 16 are simple and practical validated instruments that can be used both in the office setting and for research purposes to quickly evaluate QOL. These tests are helpful to assess improvement in both the physical and psychosocial aspects of a patient's disease [14, 31]. Lennox et al. demonstrated that the DLQI is a valid, safe and clinically applicable test in assessment of life quality related to urticaria [32]. By assuming that psychological stress triggers high levels of IL-6 in CU patients, we investigated the relationship between IL-6 levels and the quality of life. We determined that in the group with the most severe UAS, IL-6 levels were the highest and the patients’ quality of life was the worst. We came to the conclusion that IL-6 levels increase in connection with psychological stress. Increased levels of CRP were found in CU patients [6, 33–35]. However, its relationship with the disease activity score was investigated only in some studies [6, 33, 34]. In our study, serum CRP concentration was significantly higher in CU patients as compared with the healthy controls. The relationship between the disease activity score and CRP was significant in the study. The correlation of CRP and IL-6 has only been shown to be statistically significant in one study [24]. In another study where this correlation was not significant, this result was attributed to a lack of patients [6]. In our study, the correlation of IL-6 with CRP was studied and was not found to be significant statistically. We studied the relationship between the quality of life and CRP levels in patients with urticaria. According to the survey scores, we determined the highest CRP levels and the worst life conditions in the severe group. In addition, the relationship noticed between plasma IL-6 and serum CRP concentrations means that increased IL-6 levels indicate increased CRP concentration. The CRP levels are easy to determine in clinical practice, and their levels may reflect IL-6 levels, which are not routinely measured. In addition, severely affected patients may be determined using the life quality index, and a suitable treatment plan may be initiated.

The concentrations of IL-6 and CRP in circulation may be beneficial in detecting patients with more severe diseases. Such biological measurement may be particularly appropriate in the evaluation of CU patients requiring anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive treatment [8]. High levels of these markers may lead clinicians to further steps in treatment, such as immunosuppressants [6]. Consequently, besides CRP and IL-6 levels, the evaluation of the life quality index may also help to determine severely affected individuals and plan suitable treatment. Since disease activity scores were significantly associated with increased IL-6 and CRP levels, patients with high levels of acute phase reactants may be selected for advanced treatment. This may ensure better life quality with less delay in controlling disease symptoms.

References

- 1.Kushner I. The phenomenon of the acute phase response. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1982;389:39–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb22124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflamation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:448–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM. C-reactive protein: a critical update. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1805–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI18921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gauldie J, Richards C, Harnish D, et al. Interferon beta 2/B-cell stimulatory factor type 2 shares identity with monocyte-derived hepatocyte-stimulating factor and regulates the major acute pase protein response in liver cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1987;84:7251–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gabay C. Interleukin-6 and chronic inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;2:S3. doi: 10.1186/ar1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasperska-Zajac A, Sztylc J, Machura E, Jop G. Plasma IL-6 concentration correlates with clinical disease activity and serum C-reactive protein concentration in chronic urticaria patients. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:1386–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasperska-Zajac A. Does dehydroepiandrosterone influence the expression of urticaria? A mini review. Inflammation. 2011;34:362–6. doi: 10.1007/s10753-010-9242-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasperska-Zajac A. Acute-phase response in chronic urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:665–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poon E, Seed PT, Greaves MW, Kobza-Black A. The extent and nature of disability in different urticarial conditions. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:667–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Donnel BF, Lawlor F, Simpson J, et al. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabroe RA, Grattan CEH, Francis DM, et al. The autologous serum skin test: a screening test for autoantibodies in chronic idiopathic urticatia. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:446–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network; European Dermatology Forum; World Allergy Organization EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1417–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altrichter S, Boodstein N, Maurer M. Matrix metalloproteinase-9: a novel biomarker for monitoring disease activity in patients with chronic urticaria patients? Allergy. 2009;64:652–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenstreıch DL. Chronic urticaria, activated T cells, and mast cell releasability. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1986;78:1098. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(86)90256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nettis E, Dambra P, Loria MP, et al. Mast-cell phenotype in urticaria. Allergy. 2001;56:915. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lutgendorf SK, Garand L, Buckwalter KC, et al. Life stress, mood disturbance, and elevated interleukin-6 in healthy older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:M434–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.9.m434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Path G, Scherbaum WA, Bornstein SR. The role of interleukin-6 in the human adrenal glands. Eur J Clin Invest. 2000;30:91–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2000.0300s3091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin RY, Trivino MR, Curry A, et al. Interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein levels in patients with acute allergic reactions: an emergency department based study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001;87:412–6. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62923-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papanicolaou DA, Wilder RL, Manolagas SC, Chrousos GP. The pathophysiologic roles of interleukin-6 in human diseases. Ann Inter Med. 1998;128:127–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-2-199801150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:448–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan MH, Volanakis JE. Interactions of C-reactive protein complexes with the complement system. I. Consumption of human complement associated with the reaction of C reactive protein with pneumococcal C-polysaccharide and with the choline phosphatides, lecithin and sphingomyelin. J Immunol. 1974;112:2135–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegel J, Rent R, Gewurz H. Interactions of C-reactive protein with the complement system. I. Protamine-induced consumption of complement in acute phase sera. J Exp Med. 1974;140:631–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.140.3.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasperska-Zajac A, Brzoza Z, Rogala B. Plasma concentration of interleukin 6 (IL-6), and its relationship with circulating concentration of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Cytokine. 2007;39:142–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dos Santos JC, Azor MH, Nojima VY, et al. Increased circulating proinflammatory cytokines and imbalanced regulatory T-cell cytokines production in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:1433–40. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Theoharides TC. The mast cell: a neuroimmunoendocrine master player. Int J Tissue React. 1996;18:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papanicolaou D, Wilder R, Manolagas S, Chrousos G. The pathophysiologic roles of interleukin-6 in human disease. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:127–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-2-199801150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katelaris CH, Peake JE. Allergy and the skin: eczema and chronic urticaria. Med J Australia. 2006;185:517–22. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar SA, Martin BL. Urticaria and angioedema: diagnostic and treatment considerations. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1999;99(3 Suppl):S1–4. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.1999.99.3.S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baiardini I, Giardini A, Pasquali M, et al. Quality of life and patients’ satisfaction in chronic urticaria and respiratory allergy. Allergy. 2003;58:621–3. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, Sands LP. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:105–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02737863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lennox RD, Leahy MJ. Validation of the Dermatology Life Quality Index as an outcome measure for urticaria-related quality of life. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93:142–6. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61466-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tedeschi A, Asero R, Lorini M, et al. Plasma levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in chronic urticaria patients correlate with disease severity and C-reactive protein but not with circulating histamine-releasing factors. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:875–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahagi S, Mihara S, Iwamoto K, et al. Coagulation fibrinolysis and inflammation markers are associated with disease activity in patients with chronic urticaria. Allergy. 2010;65:649–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asero R, Cugno M, Tedeschi A. Activation of blood coagulation in plasma from chronic urticaria patients with negative autologous plasma skin test. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:201–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]