Abstract

Amyloid-β1-42 (Aβ) peptide effects on human models of central nervous system (CNS)-patrolling macrophages (Ms) and CD4 memory T-cells (CD4-Tms) were investigated to examine immune responses to Aβ in Alzheimer's disease. Aβ and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) elicited similar M cytokine and exosomal mRNA (ex-mRNA) responses. Aβ- and LPS-stimulated Ms from 20 ≥65-yr-old subjects generated significantly more IL-1, TNF-α, and IL-6, but not IL-8 or IL-12, and significantly more ex-mRNAs for IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-12, but not for IL-8 or IL-1, than Ms from 20 matched 21- to 45-yr-old subjects. CD4-Tm generation of IL-2, IL-4, and IFN-γ and, for young subjects, IL-10, but not IL-6, evoked by Aβ was significantly lower than with anti-T-cell antigen receptor antibodies (Abs). Abs significantly increased all CD4-Tm ex-mRNAs, but only IL-2 and IL-6 ex-mRNAs were increased by Aβ. There were no significant differences between cytokine and ex-mRNA responses of CD4-Tms from the old compared to the young subjects. M-derived serum exosomes from the old subjects had significantly higher IL-6 and IL-12 ex-mRNA levels than those from the young subjects, whereas there were no differences for CD4-Tm-derived serum exosomes. An Aβ level relevant to neurodegeneration elicited broad M cytokine and ex-mRNA responses that were significantly greater in the old subjects, but only narrow and age-independent CD4-Tm responses.—Mitsuhashi, M., Taub, D. D., Kapogiannis, D., Eitan, E., Zukley, L., Mattson, M. P., Ferrucci, L., Schwartz, J. B., Goetzl, E. J. Aging enhances release of exosomal cytokine mRNAs by Aβ1-42-stimulated macrophages.

Keywords: membrane vesicle, T cells, immunosenescence, neural proteinopathy, dementia

Human responses to amyloid-β peptides have not been elucidated fully with respect to distinct immune cell populations of the central nervous system (CNS), differences in healthy old persons, or relevance to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD). Aging of the human immune system, also termed immunosenescence, results in diminished adaptive immunity, as evidenced by the altered quantity and functions of some T- and B-cell subsets (1, 2). In contrast, immune-mediated inflammation increases with age, as shown by heightened production and higher plasma levels of the inflammatory cytokines IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-12, which are associated with increased susceptibility to metabolic and inflammatory diseases and to atherosclerosis (3–7). Possible mechanisms linking aspects of immunosenescence with a predisposition to AD remain to be established.

Antibodies specific for amyloid-β peptides appear in humans with aging and facilitate phagocytic clearance of the peptides, but also augment CNS inflammation by enhancing microglial chemotaxis and cytokine generation elicited by the peptides (8). The time course of development of anti-amyloid-β peptide antibodies in AD suggests possible beneficial effects in early disease, but such a benefit has not been proved directly, and the levels of anti-amyloid-β peptide antibodies are not unequivocally different in patients with AD than in age-matched control subjects without dementia (9).

There is general agreement that brain tissues of patients with AD have more infiltrating T cells and more inflammatory-type and senescent microglia than those of age-matched controls (10, 11). Some investigations, but not others, found that blood CD4 T-cell levels were higher, CD8 T-cell levels were lower, and B-cell levels were lower in patients with AD than in age-matched controls (12–15). Micromolar concentrations of amyloid-β peptides induce differentiation of healthy human monocytes into macrophages (Ms), evoke M migration, and enhance cytokine and chemokine production by Ms ex vivo, without consistent effects on T cells of healthy humans (10, 15, 16). The results of studies of amyloid-β peptide effects on T cells and other immune cells from patients with AD compared to those of old control subjects without dementia are also generally inconclusive or contradictory (10). In 2 studies, amyloid-β1-42 (Aβ) increased surface expression of several immunologically relevant receptors on monocytes and T cells or the T-cell level of protein kinase C more in patients with AD than in age-matched control subjects without dementia (15, 17). In numerous other studies, there were no responses of immune cells to Aβ peptides, or there were either lower responses in patients with AD or no differences between patients with AD and age-matched controls without dementia in immune cell proliferation and cytokine generation after incubation with Aβ peptides (9, 18–21). Few of these analyses included a group of younger control subjects, and only one evaluated Aβ peptide concentration dependence of responses (16).

In the current study, we examined the effects of a pathophysiologically relevant range of concentrations of oligomeric Aβ and standard immune stimuli on cytokine protein generation by human blood immune cells from old subjects without dementia and from race- and gender-matched, healthy, young controls. Exosomes harvested from cultures of immune cells of study subjects and isolated immunochemically from their serums with immune cellular specificity were also analyzed as a rich source of relevant cytokine mRNAs. We focused on Ms derived from blood monocytes by M-colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF)-induced differentiation to resemble CNS M1-type microglia (22, 23) and on CD4 memory T (CD4 Tm) cells, which are known to include the predominant set of T cells that patrol the human and rodent CNS normally (24), to provide a useful context for subsequent studies of immune cells and immune cell-derived exosomes of patients with AD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, subject selection, and collection of blood samples

Healthy study subjects were recruited at the University of California–San Francisco Medical Center, the Jewish Home of San Francisco (San Francisco, CA, USA), and the Clinical Research Unit of the National Institute on Aging (Harbor Hospital, Baltimore, MD, USA). The study procedures and potential risks were described to all participants before they signed an informed consent form that was approved along with the study protocol by the committees for human research at the three institutions. Twenty healthy subjects aged ≥65 yr, including 12 men and 8 women, were studied concurrently with 20 young control subjects aged 21 to 45 yr, who were matched with each old subject for identical gender and race (Table 1). No young or old subject had a history in the preceding 4 mo of any serious infection requiring antimicrobial treatment or an immune, autoimmune, or rheumatic disease. None of the subjects had any immunizations or had used an immunoactive drug or hormone within the prior 6 mo. Venous blood (50 ml) was taken into a heparinized syringe once from each subject, and another 10 ml of blood without heparin was added to a glass tube for serum once from 8 randomized subjects in each age group.

Table 1.

Research subject characteristics

| Designation | Age (yr) |

Racial composition |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total group, n = 20 | Women, n = 8 | Men, n = 12 | Women | Men | |

| Old | 77 ± 7.9 (65–90) | 78 ± 4.1 (70–84) | 76 ± 9.8 (65–90) | 7 C, 1 As | 8 C, 2 As, 1 Af, 1 H |

| Young | 33 ± 7.8 (21–45) | 33 ± 7.7 (24–45) | 33 ± 8.3 (21–45) | 7 C, 1 As | 8 C, 2 As, 1 Af, 1 H |

Data are expressed as means ± sd; values in parentheses indicate range. C, Caucasian; As, Asian; Af, African American; H, Hispanic.

Isolation and culture of human Ms and CD4 Tms

Heparinized blood was diluted 1:1 (v:v) with calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS−2) and centrifuged on Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) as described previously (25). Clotted blood (10 ml) was centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 min, and the supernatant serum was removed and stored at −80°C. Monocytes in 1/3 of each population of mixed mononuclear leukocytes at the Ficoll-Paque–buffer interface were purified by negative immunomagnetic selection with a kit and MS-type bead columns in a magnetic field (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA), and layers of 106/ml were incubated for 3 d in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin (complete RPMI), and 50 ng/ml human recombinant M-CSF (Miltenyi Biotec), to induce differentiation into Ms (25). The total set of CD4 Tms in 2/3 of each population of mixed mononuclear leukocytes was purified by immunomagnetic negative selection using a kit (Miltenyi-Biotec) with 2 passages through LS-type bead columns in a magnetic field. M purity was 93 to 95%, and CD4 Tm purity was 96 to 98% by flow cytometric assessment of CD14 and CD45RA vs. CD45RO, respectively (Miltenyi Biotec). Oligomeric Aβ (AnaSpec, Inc., Fremont, CA, USA) was prepared as suggested by the manufacturer, by dissolving 1 mg of lyophilized Aβ in 100 μl of 1% NH4OH followed by immediate dilution in PBS (pH 7.2) to a concentration of 50 μM, incubation at 4°C for 24 h, and storage at −80°C in 1-use 50-μl aliquots.

Ms in duplicate wells of 24-well plates at 106/ml of complete RPMI were incubated for 24 h with 20 ng/ml Escherichia coli 0111:B4 lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) or 100 nM Aβ. CD4 Tms in 24-well plates at 106/ml of complete RPMI were incubated for 72 h with 1 μg each of adherent anti-human CD3 and anti-human CD28 antibodies (25) or 100 nM Aβ. Culture supernates were removed at 24 h for Ms and at 72 h for CD4 Tms for cytokine ELISAs and cytokine exosomal mRNA (ex-mRNA) analyses. Apoptosis was quantified by a death detection kit (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Cytokine ELISAs

IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-12p70; TNF-α; and IFN-γ proteins in M- and CD4 Tm-cell media were quantified with the Human Proinflammatory-9 Ultra-Sensitive kit from Meso Scale Discovery (MSD; Rockville, MD, USA), and the MS 2400 imager (MSD) was used to determine the electrochemiluminescence of each well in the plates. IL-4 was quantified with a High-Sensitivity Single-Plex kit (MSD). Aliquots of experimental samples were diluted in culture medium to ensure that all values were in the linear portion of standard curves. All samples were assessed in duplicate. The very low levels of cytokines generated by Ms and CD4 Tms without a stimulus were subtracted from each stimulated value.

Isolation of exosomes from cell culture media and serums

Cell culture media (2 ml) were centrifuged at 2500 g for 5 min, and the supernatant was mixed thoroughly with 0.4 ml of ExoQuick exosome precipitation solution (EXOQ-TC; System Biosciences, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). After overnight incubation at 4°C, the exosome suspensions then were divided into 2 portions, and each was centrifuged at 1500 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernates were discarded; one of the exosome pellets was resuspended in 200 μl of nuclease-free water for ex-mRNA analyses, as has been described previously (26, 27); and the other pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of ELISA binding buffer (System Biosciences, Inc.), with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science) for protein extraction.

One milliliter of each serum was mixed with 1 ml of PBS−2 and centrifuged at 1500 g for 5 min. The supernatant was mixed thoroughly with 504 μl of EXOQ solution (System Biosciences), and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The resulting exosome suspensions were centrifuged at 1500 g for 30 min at 4°C, the supernates were removed, and each pellet of exosomes was resuspended in 400 μl of nuclease-free water and divided into two 200-μl portions for separate immunochemical enrichment of the supernates from the Ms and CD4 Tms. The first step in enrichment of cell-specific serum exosomes was negative selection by 10 μl of the respective cocktails of biotinylated antibodies (Miltenyi Biotec) used to isolate monocytes and CD4 Tms from blood mixed mononuclear leukocytes per 100 μl of sample, followed by incubation for 1 h at 4°C. Instead of using antibiotin antibody beads and columns, as for the cells, each sample was incubated with 20 μl of streptavidin-agarose resin (ThermoFisher Scientific, Inc., Rockford, IL, USA) for 2 h at 4°C, with rocking, and centrifuged at 200 g for 10 min at 4°C before recovery of each 130 μl supernatant. The second step for each pair of samples was positive enrichment of M-derived exosomes with 2 μg of biotinylated goat anti-human integrin β2 (CD18/11) antibodies (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) and of CD4 Tm-derived exosomes with 2 μg of biotinylated mouse anti-human CD3 monoclonal antibody (Biolegend, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) for 2 h at 4°C, followed by incubation of each sample with 20 μl of streptavidin-agarose resin for 1 h at 4°C, with rocking. After centrifugation at 200 g for 10 min at 4°C, each supernatant was removed and each pellet resuspended in 150 μl of 0.05 M glycine-HCl in nuclease-free water (pH 3.0) at 4°C. These suspensions were centrifuged at 200 g for 10 min at 4°C before harvesting each supernatant, adjusting pH to 7.0 with 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and removing portions for separate analyses of the ex-mRNAs and proteins, as for the cell media exosomes.

For comparison with the ExoQuick precipitation methods, 1 ml aliquots of serums from 4 old and 4 young subjects were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min at 4°C to remove nonvesicle cellular constituents, and the supernates were centrifuged at 100,000 g for 2 h at 4°C to sediment the exosomes. The pellets were resuspended in 0.5 ml of PBS−2 and recentrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4°C, and the resultant pellets were processed in the same manner as those isolated with the ExoQuick technique for analyses of ex-mRNAs and proteins.

Characterization of exosomes from cell culture media and serums

Representative suspensions of exosomes were diluted 1:20 to 1:100 to permit counting them in the range of 3–15 × 108/ml, with the NS500 nanoparticle tracking analysis system (NanoSight, Amesbury, UK). The exosomes were visualized by their scattering of a focused laser beam and the collection of the scattered light by a standard optical microscope fitted with a CCD video camera. Five exposures of 20 s each were recorded from fields chosen randomly by a computer operating with NanoSight software, which also calculated their size according to the Stokes-Einstein equation. Exosome proteins were extracted and quantified by ELISA kits for human CD3 and CD18/11 (MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA) and CD81 (System Biosciences, Inc.), with human purified recombinant CD81 antigen (Origene Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA), according to the suppliers' directions. Replicate portions of some M exosomes were treated with 20 ng/μl of RNase A (Qiagen Corp., Germantown, MD, USA) before PCR analyses.

Real-time PCR quantification of cytokine ex-mRNAs

Cell culture media exosomes assayed directly and suspensions of exosomes purified from cell culture media or serum were applied to an exosome-capture filter plate (Hitachi Chemical Research Center, Irvine, CA, USA) and centrifuged at 2000 g for 5 min at 4°C. Exosomes trapped on the filter plate were lysed by adding 50 μl of lysis buffer followed by incubation at 55°C for 10 min. The lysates were transferred to oligo(dT)-coated microplates (Hitachi Chemical Research Center) for poly(A)+ RNA isolation, followed by cDNA synthesis on the same plate, as described (27). Each cDNA was amplified by real-time PCR with the iTaqSYBR system (Bio-Rad, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) in a thermal cycler (Prism 7900; Applied Biosystems/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) (Supplemental Table S1 and ref. 27). PCR conditions were 95°C for 10 min followed by either 32 or 40 cycles of 65°C for 1 min and 95°C for 30 s. The melting curve was always analyzed to confirm that PCR signals were derived from a single PCR product. The cycle threshold (Ct) was determined by analytical software (SDS system software; Applied Biosystems). Each ex-mRNA result is expressed relative to the standard β-actin (ACTB) by the following formula: 32- or 40-cytokine unknown divided by 32- or 40-ACTB × 100. Values for media exosomes of unstimulated Ms and CD4 Tms were often undetectable and were always less than one-third of those for stimulated cells, so that only levels of ex-mRNAs for stimulated Ms and CD4 Tms are reported.

Statistical analyses

The unpaired t test with the Bonferroni correction for multiple determinations was used to calculate the significance of differences between values for unstimulated and stimulated cells, and between those for old and young subjects. Levels of significance for each analysis are provided in the figure legends.

RESULTS

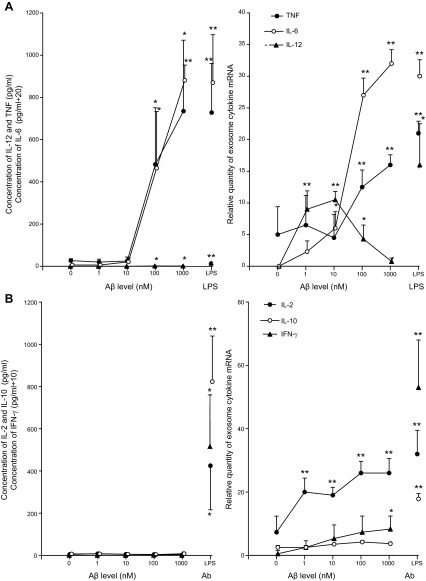

Purified Ms and CD4 Tms from 4 healthy, young subjects (2 female and 2 male) were incubated with a pathophysiologically relevant range of concentrations of oligomeric Aβ, and the resultant media were analyzed for selected cytokine proteins and ex-mRNAs (Fig. 1). Ms secreted TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 at significantly elevated levels in response to 100 and 1000 nM Aβ, which for each cytokine were similar in magnitude to those evoked by the highly-active stimulus LPS (Fig. 1A). Secretion of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 by unstimulated Ms from 4 healthy, old subjects (2 female and 2 male) were 24 ± 10, 6.2 ± 2.5, and 0.15 ± 0.11 pg/ml, respectively, and were not significantly different from the corresponding values for the young subjects of 27 ± 9.3, 6.0, ± 4.2, and 0.13 ± 0.05 pg/ml. Exosomes shed by Ms and analyzed by an established method (27) contained significantly elevated levels of both TNF-α and IL-6 mRNAs in response to 100 and 1000 nM Aβ, and of IL-12 mRNA in response to 1–100 nM Aβ. At these concentrations of Aβ, the levels of M ex-mRNAs for all 3 cytokines were similar in magnitude to those elicited by LPS. Treatment of M exosome samples from each subject with 20 ng/μl of RNase A did not alter the results of the PCR analyses of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 ex-mRNAs. The relative levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 ex-mRNAs in exosomes shed by unstimulated Ms from 4 healthy old subjects (2 female and 2 male) were 5.3 ± 3.9 pg/nl, nondetectable (ND), and ND, respectively, and were not significantly different from the corresponding values for the young subjects of 5.0 ± 4.4 pg/ml, ND, and ND.

Figure 1.

Concentration dependence of Aβ stimulation of immune cell cytokine pathways. Points and bars depict means ± sd of results for 4 healthy young subjects. Ms were stimulated with Aβ or 10 ng/ml of LPS for 24 h (A), and CD4 Tms were stimulated with Aβ or adherent Ab for 72 h (B). Left panels: secreted cytokine protein concentrations. Right panels: relative levels of ex-mRNAs. Statistical significance of each increase evoked by Aβ, LPS, or Abs, compared to the level in the absence of a stimulus, was calculated with an unpaired t test and the Bonferroni correction for multiple determinations. *P < 0.008; **P < 0.001.

In contrast, the very low levels of IL-2, IL-10, and IFN-γ secreted by CD4 Tms stimulated with all concentrations of Aβ did not differ from the CD4 Tm-generated levels in the absence of Aβ and were 2 orders of magnitude lower than those elicited by adherent anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 antibodies (Abs; Fig. 1B). Secretion of IL-2, IL-10, and IFN-γ by unstimulated CD4 Tms from the 4 healthy old subjects (2 female and 2 male) were 4.6 ± 3.2, 6.1 ± 3.4, and 0.48 ± 0.13 pg/ml, respectively, and were not significantly different from the corresponding values for the young subjects of 5.0 ± 3.5, 6.8 ± 2.6, and 0.54 ± 0.16 pg/ml. The IL-2 ex-mRNA contents of exosomes shed by CD4 Tms in response to 1–1000 nM Aβ were significantly higher than those without Aβ and attained a magnitude similar to that elicited by Abs (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the level of IFN-γ ex-mRNA in exosomes shed by CD4 Tms was only significantly higher than that without Aβ in response to 1000 nM Aβ, and none of the levels of IL-10 ex-mRNA in exosomes shed by CD4 Tms were significantly higher than those without Aβ. The relative levels of IL-2, IL-10, and IFN-γ ex-mRNAs in exosomes shed by unstimulated CD4 Tms from 4 healthy old subjects (2 female and 2 male) were 6.4 ± 3.8, 2.9 ± 1.1, and 0.6 ± 0.4, respectively, and were not significantly different from the corresponding values for the young subjects of 7.3 ± 5.1, 2.5 ± 0.6, and 0.5 ± 0.3. Overall, these results suggest that ex-mRNA shedding is more responsive to Aβ than is cytokine protein secretion and led to the selection of 100 nM Aβ for stimulation of Ms and CD4 Tms in all subsequent studies.

To examine the possibility that Aβ may have cytotoxic effects at the concentration used in all subsequent studies, we incubated 106 Ms and CD4 Tms from 4 young and 4 old healthy subjects for 24 and 72 h, respectively, with 100 and 1000 nM Aβ. Apoptosis was quantified, as described previously (28), based on immunochemical immobilization and measurement of nucleosomes. The mean basal levels of apoptosis of Ms and CD4 Tms from the young and old subjects were not increased significantly by the standard stimulating concentration of 100 nM Aβ. However, 1000 nM Aβ significantly increased the respective levels of apoptosis of Ms from the young and old subjects by 10 ± 6 and 14 ± 7%, respectively (P<0.05 for both), and of CD4 Tms by 16 ± 5% (P<0.01) and 19 ± 9% (P<0.05), respectively.

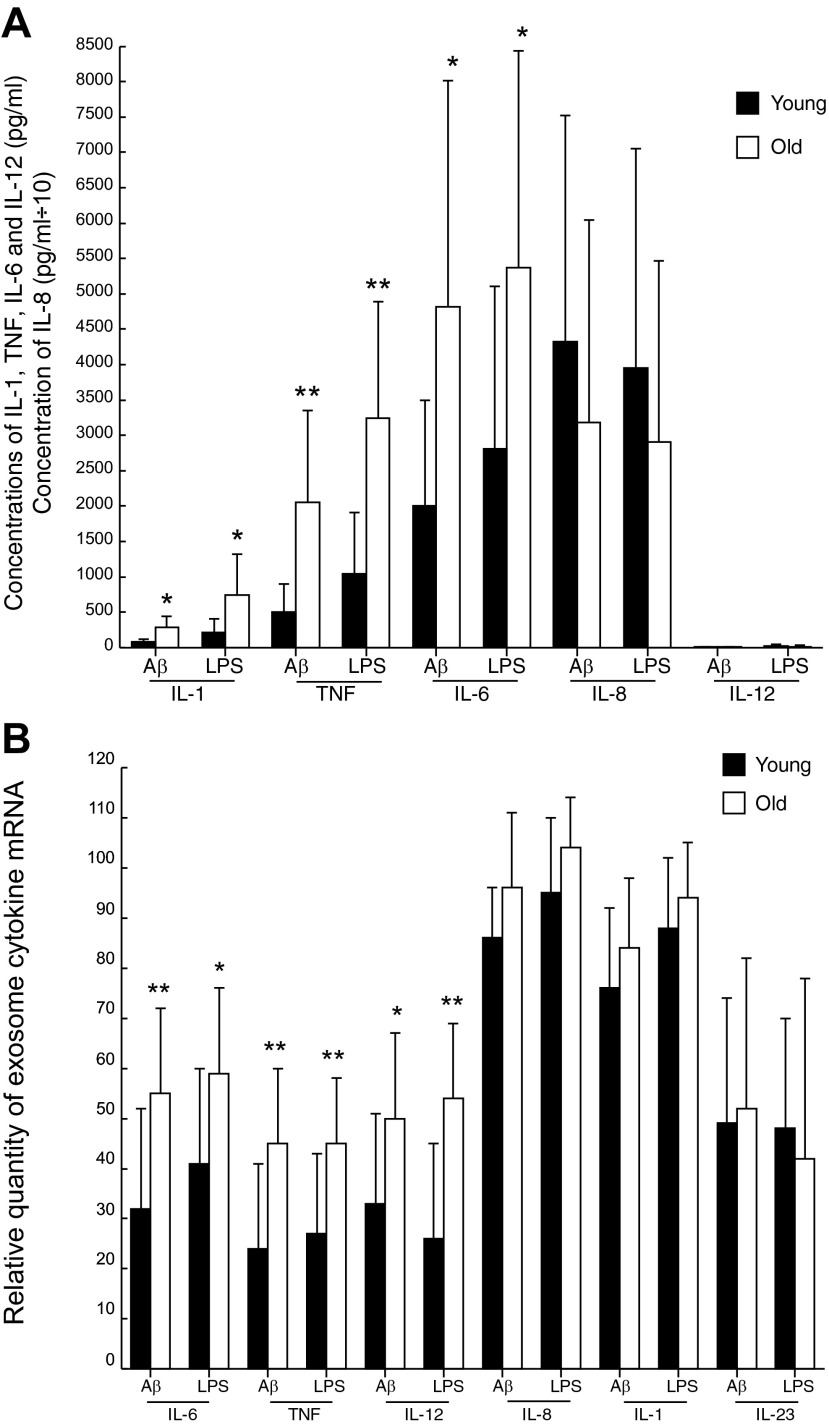

A more detailed evaluation of the effects of Aβ and LPS on Ms from the groups of 20 healthy old and 20 matched young subjects (Table 1) revealed significantly greater production of IL-1, TNF-α, and IL-6 but not of IL-8 or IL-12 proteins by Aβ- and LPS-stimulated Ms from the old subjects than by those from the young subjects (Fig. 2A). For IL-1, TNF-α, and IL-6, the mean levels were 3.54-, 4.05-, and 2.41-fold higher, respectively, in the old than in the young subjects with the application of Aβ and 3.53-, 3.10-, and 1.91-fold higher with LPS. Age dependence of the profile of shed ex-mRNAs differed from that of cytokine proteins, with significantly greater levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-12 mRNAs, but no differences in IL-8, IL-1, or IL-23 mRNAs for Aβ- and LPS-stimulated Ms from the old subjects compared to those from the young subjects (Fig. 2B). For IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-12, the mean levels were 1.72-, 1.88-, and 1.52-fold higher, respectively, in the old than in the young subjects with Aβ and 1.44-, 1.67-, and 2.08-fold higher with LPS.

Figure 2.

Greater increases in the generation of some cytokine proteins (A) and ex-mRNAs (B) by stimulated Ms of old than those of young subjects. Columns and bars depict means ± sd of results for the total group of young or old healthy subjects. Ms were stimulated with 100 nM Aβ or 10 ng/ml of LPS for 24 h. Statistical significance of differences between corresponding stimulated values for young and old groups was calculated with an unpaired t test and the Bonferroni correction for multiple determinations. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001 (A); *P < 0.008, **P < 0.001 (B).

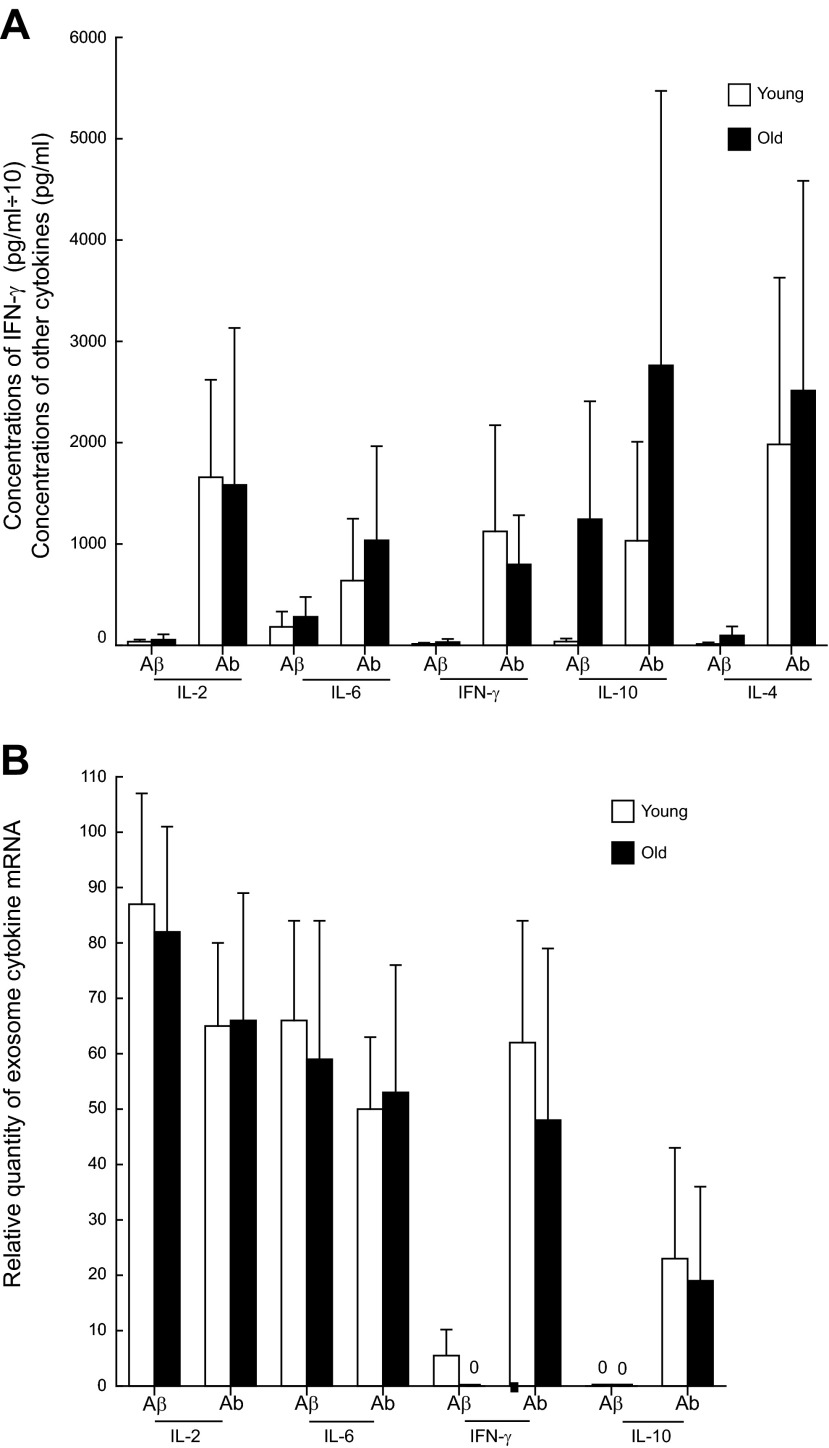

The generation of cytokine proteins by CD4 Tms from the groups of healthy old and matched young subjects showed 2 distinctions when compared to the results for Ms (Fig. 3A). First, the level of cytokine protein evoked by Aβ was significantly lower than that evoked by Abs for IL-2, IL-4, and IFN-γ in the old and the young subjects and for IL-10 in the young subjects (all P<0.01). Second, the levels of the cytokine proteins generated by CD4 Tms of the old subjects were not significantly different from those generated by CD4 Tms of the young subjects. The levels of IL-2 and IL-6 ex-mRNAs shed by CD4 Tms from the groups of healthy old and matched young subjects were similarly significant with both Aβ and Abs stimulation (Fig. 3B), as had been shown for IL-2 (Fig. 1B). Also, as already shown (Fig. 1B), stimulation with Abs, but not with 100 nM Aβ, significantly elevated shedding of IFN-γ and IL-10 ex-mRNAs by CD4 Tms of the healthy old and matched young subjects (Fig. 3B). Most important, there were no significant differences between the shedding of any ex-mRNAs by CD4 Tms of the old subjects and the shedding of ex-mRNAs in the young subjects.

Figure 3.

Similar increases in generation of cytokine proteins (A) and ex-mRNAs (B) by stimulated CD4 Tms of old and young subjects. Columns and bars depict means ± sd of results for the total group of young or old healthy subjects. CD4 Tms were stimulated with 100 nM Aβ or Ab for 72 h. None of the differences between corresponding stimulated values for the young and old groups was statistically significant, as calculated with an unpaired t test and the Bonferroni correction for multiple determinations.

To examine the possibility that the observed differences in ex-mRNAs were attributable to differences in the number or size of the exosomes in the preparations studied, we evaluated these variables in randomly chosen samples of exosomes isolated by well-described methods (System Biosciences, Inc.; ref. 27). The number of exosomes in cell culture media was higher for CD4 Tms than for Ms, presumably as a result in part of the 3-fold longer period of incubation (Tables 2 and 3). There were no significant differences between the exosomal sizes of the two types of immune cells. Neither age nor cellular stimulation significantly affected exosomal size or number in the cell media. Similarly, the number and size of M-derived serum exosomes were age independent (Table 4). Whether M-derived serum exosomes were isolated initially by precipitation with ExoQuick solution or by ultracentrifugation, their number and size were the same.

Table 2.

Characteristics of exosomes from M medium

| Subject group | n/ml (×109) | Diameter (nm) | CD81 (pg/ml) | CD18/11 (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | ||||

| Unstimulated | 0.53 ± 0.18 | 137 ± 8 | 400 ± 41 | 55 ± 5.5 |

| Stimulated | 0.70 ± 0.36 | 121 ± 20 | 406 ± 9.9 | 53 ± 8.4 |

| Old | ||||

| Unstimulated | 0.66 ± 0.16 | 123 ± 15 | 409 ± 19 | 55 ± 13 |

| Stimulated | 0.60 ± 0.19 | 121 ± 13 | 396 ± 29 | 55 ± 3.1 |

Data are expressed as means ± sd (n=6/group). Values for CD81 and CD18/11 are picograms for the total number of exosomes in 1 ml of initial medium. Stimulus was LPS.

Table 3.

Characteristics of exosomes from CD4 Tm medium

| Subject group | n/ml (×109) | Diameter (nm) | CD81 (pg/ml) | CD3 (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | ||||

| Unstimulated | 3.21 ± 0.36 | 129 ± 16 | 2049 ± 76 | 56 ± 7.6 |

| Stimulated | 4.18 ± 1.13 | 130 ± 18 | 2041 ± 93 | 62 ± 11 |

| Old | ||||

| Unstimulated | 3.31 ± 0.44 | 130 ± 12 | 2050 ± 209 | 58 ± 3.8 |

| Stimulated | 4.01 ± 0.78 | 130 ± 13 | 2098 ± 156 | 58 ± 5.5 |

Data are expressed as means ± sd; (n=6/group). Values for CD81 and CD3 are picograms for the total number of exosomes in 1 ml of initial medium. Stimulus was Abs.

Table 4.

Characteristics of M-derived exosomes of serums

| Subject group |

n/ml (×109) |

Diameter (nm) |

CD81 (pg/ml) |

CD18/11 (pg/ml) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ExoQ | UC | ExoQ | UC | ExoQ | UC | ExoQ | UC | |

| Young | 0.99 ± 0.16 | 0.91 ± 0.10 | 122 ± 19 | 120 ± 16 | 726 ± 68 | 729 ± 83 | 69 ± 11 | 68 ± 13 |

| Old | 0.99 ± 0.12 | 0.94 ± 0.15 | 124 ± 16 | 124 ± 19 | 736 ± 19 | 728 ± 38 | 68 ± 11 | 66 ± 10 |

Data are expressed as means ± sd; (n=4/group). Values for CD81 and CD18/11 are picograms for the total number of exosomes in 1 ml of initial medium. ExoQ, ExoQuick precipitation solution; UC, ultracentrifugation.

The quantity of the CD81 tetraspan protein marker in exosome preparations was proportional to the number of exosomes and was not influenced by isolation method, age, or prior cellular stimulation (Tables 2–4). The levels of CD18/11 in exosomes from M medium (Table 2) and of CD3 in exosomes from CD4 Tm medium (Table 3) were both lower than those of CD81 in the respective preparations, but were sufficiently high to enable enrichment by immunochemical absorption techniques.

Cytokine mRNAs were quantified in exosomes isolated from serums of 8 young subjects and 8 matched old subjects after immunochemical enrichment for an M or a CD4 Tm source (Fig. 4). The levels of IL-6 and IL-12 mRNAs, but not that of TNF-α mRNA, in M-derived exosomes from serums of the old subjects was significantly higher than that in serums of the young subjects. The mean level of IL-2 ex-mRNA in CD4 Tm-derived exosomes from serums of the young subjects was higher than the undetectable quantity in the serums of the old subjects, but the difference did not attain statistical significance. Neither IL-10 mRNA nor IFN-γ mRNA was detected in CD4 Tm-derived exosomes from the serums of the old or young subjects (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Cytokine mRNAs in M- and CD4 Tm-derived serum exosomes of old and young subjects. Columns and bars depict means ± se of results for groups of 8 young and 8 matched old healthy subjects. No mRNA encoding IL-10 or IFN-γ was detected in CD4 Tm serum exosomes. Statistical significance of differences between values for young and old groups was calculated with an unpaired t test and the Bonferroni correction for multiple determinations. *P < 0.017, **P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Analyses of the cell type–specific cytokine proteins secreted and ex-mRNAs shed concurrently by stimulated Ms and CD4 Tms revealed distinct differences between the profiles of proteins and mRNAs from the same source. Unstimulated Ms and CD4 Tms secreted the same respective levels of cytokine proteins and shed the same respective levels of exosome mRNAs, whether derived from the young or old subjects (Results, paragraphs 1 and 2). The release of cytokine proteins and ex-mRNAs by Ms from the young and old subjects was similar in magnitude, whether the stimulus was LPS or an optimal concentration of Aβ (Figs. 1A and 2). In contrast, the same release levels from CD4 Tms varied with the individual cytokine (Figs. 1B and 3). For all cytokines examined, CD4 Tm cytokine protein levels were significantly lower with Aβ than with Abs stimulation, except for IL-10 in old subjects and IL-6 (Fig. 3A). CD4 Tm IFN-γ and IL-10 ex-mRNA levels were also significantly lower with Aβ than with Abs stimulation, but IL-2 and IL-6 ex-mRNA levels were indistinguishable (Fig. 3B). There were broadly greater responses of Ms from the old than from the young subjects to Aβ and LPS stimulation for IL-1, TNF-α, and IL-6 proteins and for IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-12 ex-mRNAs (Fig. 2). Differences in inflammation in the old vs. the young subjects were reflected in more sets of M ex-mRNAs than in sets of M cytokine proteins. This result contrasts again with CD4 Tms, where no cytokine protein or ex-mRNA level was higher in the old than in the young subjects (Fig. 3).

Possible physiological and pathobiological consequences of differences between the levels of secretion of some cytokine proteins and the extent of exportation of their ex-mRNAs by Ms and CD4 Tms may be tentatively interpreted in relation to the functional roles of exosomes. Exosomes released from one type of immune cell and taken up by other types have been shown to be capable of substantially altering the cytotoxic, inflammatory, and immunosuppressive activities of the recipient set of immune cells (29–32). Diverse mechanisms may be involved in this form of intercellular communication, including transfer of microbial proteins, various regulatory RNAs, and enzymes that generate immunoregulatory mediators such as adenosine (33–35). Thus, the shedding of IL-12 ex-mRNA by stimulated Ms that secrete only minimal quantities of IL-12 protein (Figs. 1 and 2) may lead to a major amplification of the effects of IL-12 after the ex-mRNA is taken up by other cells at a site with the capacity for prolonged generation of this cytokine. Exosomes are also thought to be capable of delivering native mRNAs to sites farther from their cellular source than the often paracrine and juxtacrine destinations of cytokine proteins.

Even less is known of the means by which stimuli such as Aβ direct the loading of exosomes with cytokine mRNAs for extracellular delivery. Stimulation of Ms and CD4 Tms from either age group with LPS and Abs, respectively, did not affect the number or size of the exosomes shed into the culture medium or their surface expression of selected proteins (Tables 2–4). Limited studies with 100 nM Aβ similarly showed no change in shed exosomal properties. However, Aβ had prominent enhancing effects on the exosomal contents of cytokine ex-mRNAs that were broader in Ms than in CD4 Tms (Figs. 2B vs. 3B). Aβ binds to many cellular proteins that are more highly expressed in macrophages than in T cells, exemplified by the complement receptor CR3, IgG FcγRIIb receptor, chemotactic factor G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), formyl peptide receptor-like 1 [FPRL1], scavenger receptors SR-A and receptor for advanced-glycosylation endproducts (RAGE), oxidized LDL receptor CD36, and heparan sulfate (36). However, any relationship of occupancy of these receptors to Aβ and subsequent signaling events in the exosomal pathways remains to be elucidated. The distinctive complexities of exosomal functions in immunity alone suggest that traditional immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory drugs are unlikely to affect exosomal activities similarly to their established influence on the classic generation and effects of cytokines.

The ability to isolate M- and CD4 Tm-derived exosomes from serum and plasma may provide an easily available portal for studies of the activities of these immune cells in immune and nonimmune tissues. That the levels of inflammatory cytokine mRNAs in M-derived serum exosomes were higher in the old than in the young subjects is an initial suggestion of the potential usefulness of investigations of integrated systemic pools of exosomes derived from one type of cell (Fig. 4). However, it is not currently clear to what extent the serum concentration of exosomes from one type of cell reflects the levels of exosome generation by this type of cell in one or more tissues, the activity of systems that transport exosomes from tissues to blood, and the removal of the exosomes from blood through uptake by other cells and biodegradation. It also remains to be examined whether disease-altered mRNA contents of exosomes in affected tissues and tissue fluids lead to similar RNA changes in the set of exosomes isolated from serum or plasma (37). Plasma exosomes maintain the capacity to deliver regulatory miRNAs to both monocytes and lymphocytes, as one indication of preservation of immune functional integrity (38). Preliminary data suggest that transport-active proteins on exosomal surfaces control selective distribution within organ systems, but the proteins that result in export to blood are not known (39). We also have not begun to address the ability of immune cell exosomes to transport active cytokines and other immune proteins through this alternative pathway to the extracellular space (40). A greater understanding of the pathophysiological relevance of RNAs and proteins transported by exosomes from distinct tissue sources of limited accessibility into readily accessible blood may reveal unique diagnostic value for these data in some diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by endowment fund income of the Jewish Home of San Francisco, by the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Institute on Aging, and by funds from the Edward A. Dickson Professorship at the University of California, San Francisco.

The authors are grateful to Judith H. Goetzl for expert preparation of the graphic illustrations. Dr. Charles Hesdorffer (Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Washington, DC, USA) provided constant support for the research.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- Aβ

- amyloid-β1-42

- AD

- Alzheimer's disease

- ex-mRNA

- exosomal mRNA

- CD4 Tm

- CD4 memory T

- Abs

- anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 antibodies

- CNS

- central nervous system

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- M

- macrophage

- M-CSF

- M-colony-stimulating factor

- ND

- nondetectable

- PBS−2

- calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline

REFERENCES

- 1. Grubeck-Loebenstein B., Wick G. (2002) The aging of the immune system. Adv. Immunol. 80, 243–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Montecino-Rodriguez E., Berent-Maoz B., Dorshkind K. (2013) Causes, consequences, and reversal of immune system aging. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 958–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bruunsgaard H., Pedersen A. N., Schroll M., Skinhoj P., Pedersen B. K. (2000) TNF-alpha, leptin, and lymphocyte function in human aging. Life Sci. 67, 2721–2731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bruunsgaard H., Skinhoj P., Pedersen A. N., Schroll M., Pedersen B. K. (2000) Ageing, tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and atherosclerosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 121, 255–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rea I. M., McNerlan S. E., Alexander H. D. (2000) Total serum IL-12 and IL-12p40, but not IL-12p70, are increased in the serum of older subjects; relationship to CD3(+)and NK subsets. Cytokine 12, 156–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kirwan J. P., Krishnan R. K., Weaver J. A., Del Aguila L. F., Evans W. J. (2001) Human aging is associated with altered TNF-alpha production during hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 281, E1137–E1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pedersen M., Bruunsgaard H., Weis N., Hendel H. W., Andreassen B. U., Eldrup E., Dela F., Pedersen B. K. (2003) Circulating levels of TNF-alpha and IL-6-relation to truncal fat mass and muscle mass in healthy elderly individuals and in patients with type-2 diabetes. Mech. Ageing Dev. 124, 495–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Strohmeyer R., Kovelowski C. J., Mastroeni D., Leonard B., Grover A., Rogers J. (2005) Microglial responses to amyloid beta peptide opsonization and indomethacin treatment. J. Neuroinflammation 2, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baril L., Nicolas L., Croisile B., Crozier P., Hessler C., Sassolas A., McCormick J. B., Trannoy E. (2004) Immune response to Abeta-peptides in peripheral blood from patients with Alzheimer's disease and control subjects. Neurosci. Lett. 355, 226–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Britschgi M., Wyss-Coray T. (2007) Systemic and acquired immune responses in Alzheimer's disease. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 82, 205–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Streit W. J., Braak H., Xue Q. S., Bechmann I. (2009) Dystrophic (senescent) rather than activated microglial cells are associated with tau pathology and likely precede neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 118, 475–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lombardi V. R., Garcia M., Rey L., Cacabelos R. (1999) Characterization of cytokine production, screening of lymphocyte subset patterns and in vitro apoptosis in healthy and Alzheimer's Disease (AD) individuals. J. Neuroimmunol. 97, 163–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Richartz-Salzburger E., Batra A., Stransky E., Laske C., Kohler N., Bartels M., Buchkremer G., Schott K. (2007) Altered lymphocyte distribution in Alzheimer's disease. J. Psychiatr. Res. 41, 174–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bonotis K., Krikki E., Holeva V., Aggouridaki C., Costa V., Baloyannis S. (2008) Systemic immune aberrations in Alzheimer's disease patients. J. Neuroimmunol. 193, 183–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pellicano M., Bulati M., Buffa S., Barbagallo M., Di Prima A., Misiano G., Picone P., Di Carlo M., Nuzzo D., Candore G., Vasto S., Lio D., Caruso C., Colonna-Romano G. (2010) Systemic immune responses in Alzheimer's disease: in vitro mononuclear cell activation and cytokine production. J. Alzheimers Dis. 21, 181–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fiala M., Zhang L., Gan X., Sherry B., Taub D., Graves M. C., Hama S., Way D., Weinand M., Witte M., Lorton D., Kuo Y. M., Roher A. E. (1998) Amyloid-beta induces chemokine secretion and monocyte migration across a human blood–brain barrier model. Mol. Med. 4, 480–489 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miscia S., Ciccocioppo F., Lanuti P., Velluto L., Bascelli A., Pierdomenico L., Genovesi D., Di Siena A., Santavenere E., Gambi F., Ausili-Cefaro G., Grimley P. M., Marchisio M., Gambi D. (2009) Abeta(1–42) stimulated T cells express P-PKC-delta and P-PKC-zeta in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Aging 30, 394–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Trieb K., Ransmayr G., Sgonc R., Lassmann H., Grubeck-Loebenstein B. (1996) APP peptides stimulate lymphocyte proliferation in normals, but not in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 17, 541–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giubilei F., Antonini G., Montesperelli C., Sepe-Monti M., Cannoni S., Pichi A., Tisei P., Casini A. R., Buttinelli C., Prencipe M., Salvetti M., Ristori G. (2003) T cell response to amyloid-beta and to mitochondrial antigens in Alzheimer's disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 16, 35–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Monsonego A., Zota V., Karni A., Krieger J. I., Bar-Or A., Bitan G., Budson A. E., Sperling R., Selkoe D. J., Weiner H. L. (2003) Increased T cell reactivity to amyloid beta protein in older humans and patients with Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 415–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jozwik A., Landowski J., Bidzan L., Fulop T., Bryl E., Witkowski J. M. (2012) Beta-amyloid peptides enhance the proliferative response of activated CD4CD28 lymphocytes from Alzheimer disease patients and from healthy elderly. PLoS One 7, e33276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lutter D., Ugocsai P., Grandl M., Orso E., Theis F., Lang E. W., Schmitz G. (2008) Analyzing M-CSF dependent monocyte/macrophage differentiation: expression modes and meta-modes derived from an independent component analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stansley B., Post J., Hensley K. (2012) A comparative review of cell culture systems for the study of microglial biology in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neuroinflammation 9, 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mueller S. N., Gebhardt T., Carbone F. R., Heath W. R. (2013) Memory T cell subsets, migration patterns, and tissue residence. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 31, 137–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goetzl E. J., Huang M. C., Kon J., Patel K., Schwartz J. B., Fast K., Ferrucci L., Madara K., Taub D. D., Longo D. L. (2010) Gender specificity of altered human immune cytokine profiles in aging. FASEB J. 24, 3580–3589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kadiu I., Narayanasamy P., Dash P. K., Zhang W., Gendelman H. E. (2012) Biochemical and biologic characterization of exosomes and microvesicles as facilitators of HIV-1 infection in macrophages. J. Immunol. 189, 744–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mitsuhashi M. (2010) Ex vivo simulation of leukocyte function: stimulation of specific subset of leukocytes in whole blood followed by the measurement of function-associated mRNAs. J. Immunol. Methods 363, 95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang M. C., Greig N. H., Luo W., Tweedie D., Schwartz J. B., Longo D. L., Ferrucci L., Ershler W. B., Goetzl E. J. (2011) Preferential enhancement of older human T cell cytokine generation, chemotaxis, proliferation and survival by lenalidomide. Clin. Immunol. 138, 201–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang H., Xie Y., Li W., Chibbar R., Xiong S., Xiang J. (2011) CD4(+) T cell-released exosomes inhibit CD8(+) cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses and antitumor immunity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 8, 23–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lugini L., Cecchetti S., Huber V., Luciani F., Macchia G., Spadaro F., Paris L., Abalsamo L., Colone M., Molinari A., Podo F., Rivoltini L., Ramoni C., Fais S. (2012) Immune surveillance properties of human NK cell-derived exosomes. J. Immunol. 189, 2833–2842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Walters S. B., Kieckbusch J., Nagalingam G., Swain A., Latham S. L., Grau G. E., Britton W. J., Combes V., Saunders B. M. (2013) Microparticles from mycobacteria-infected macrophages promote inflammation and cellular migration. J. Immunol. 190, 669–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Naslund T. I., Gehrmann U., Qazi K. R., Karlsson M. C., Gabrielsson S. (2013) Dendritic cell-derived exosomes need to activate both T and B cells to induce antitumor immunity. J. Immunol. 190, 2712–2719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bhatnagar S., Schorey J. S. (2007) Exosomes released from infected macrophages contain Mycobacterium avium glycopeptidolipids and are proinflammatory. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 25779–25789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thery C., Ostrowski M., Segura E. (2009) Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 581–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smyth L. A., Ratnasothy K., Tsang J. Y., Boardman D., Warley A., Lechler R., Lombardi G. (2013) CD73 expression on extracellular vesicles derived from CD4 CD25 Foxp3 T cells contributes to their regulatory function. Eur. J. Immunol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Verdier Y., Penke B. (2004) Binding sites of amyloid beta-peptide in cell plasma membrane and implications for Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 5, 19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Levanen B., Bhakta N. R., Torregrosa Paredes P., Barbeau R., Hiltbrunner S., Pollack J. L., Skold C. M., Svartengren M., Grunewald J., Gabrielsson S., Eklund A., Larsson B. M., Woodruff P. G., Erle D. J., Wheelock A. M. (2013) Altered microRNA profiles in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid exosomes in asthmatic patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 131, 894–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wahlgren J., De L. K. T., Brisslert M., Vaziri Sani F., Telemo E., Sunnerhagen P., Valadi H. (2012) Plasma exosomes can deliver exogenous short interfering RNA to monocytes and lymphocytes. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alvarez-Erviti L., Seow Y., Yin H., Betts C., Lakhal S., Wood M. J. (2011) Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 341–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Turola E., Furlan R., Bianco F., Matteoli M., Verderio C. (2012) Microglial microvesicle secretion and intercellular signaling. Front. Physiol. 3, 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.