Abstract

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases should ensure high accuracy in tRNA aminoacylation. However, the absence of significant structural differences between amino acids always poses a direct challenge for some aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, such as leucyl-tRNA synthetase (LeuRS), which require editing function to remove mis-activated amino acids. In the cytoplasm of the human pathogen Candida albicans, the CUG codon is translated as both Ser and Leu by a uniquely evolved CatRNASer(CAG). Its cytoplasmic LeuRS (CaLeuRS) is a crucial component for CUG codon ambiguity and harbors only one CUG codon at position 919. Comparison of the activity of CaLeuRS-Ser919 and CaLeuRS-Leu919 revealed yeast LeuRSs have a relaxed tRNA recognition capacity. We also studied the mis-activation and editing of non-cognate amino acids by CaLeuRS. Interestingly, we found that CaLeuRS is naturally deficient in tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing for non-cognate norvaline while displaying a weak tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing capacity for non-cognate α-amino butyric acid. We also demonstrated that post-transfer editing of CaLeuRS is not tRNALeu species-specific. In addition, other eukaryotic but not archaeal or bacterial LeuRSs were found to recognize CatRNASer(CAG). Overall, we systematically studied the aminoacylation and editing properties of CaLeuRS and established a characteristic LeuRS model with naturally deficient tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing, which increases LeuRS types with unique editing patterns.

INTRODUCTION

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) are essential components required to establish the genetic code during protein biosynthesis by coupling specific amino acids with their cognate tRNAs in a two-step aminoacylation reaction (1,2). This process requires amino acid activation by condensation with ATP to form the aminoacyl-adenylate (aa-AMP) and pyrophosphate; the activated amino acid is then transferred to the cognate tRNA to yield the aminoacyl-tRNA (aa-tRNA), which is then transferred to the protein biosynthesis machinery as a building block (1). Aminoacylation of tRNA requires adequate efficiency and accuracy, which requires tightly regulated control of the speed of the aa-tRNA production for the ribosome and the risk of generation of aberrant aa-tRNA pairs (3–5). Transfer RNA always harbors various identity determinants and/or anti-determinants, facilitating selection of the correct tRNA from a large pool of tRNA species (6). However, the specificity of aaRS is greatly challenged by the presence of various types of amino acids and their analogues and the fact that amino acids differ only in the side-chain. AaRSs that do not show an overall selectivity above 1 in 3000 are predicted to require some form of proofreading (editing) mechanism to maintain sufficient accuracy during aa-tRNA synthesis (5,7,8). Editing activity has evolved in half of the currently identified aaRSs to remove any aberrantly produced aa-AMP (pre-transfer editing) and/or aa-tRNA (post-transfer editing). This is an essential checkpoint that ensures translational fidelity (5). Pre-transfer editing can be further divided into tRNA-independent and tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing. In tRNA-independent pre-transfer editing, the non-cognate aa-AMP is hydrolyzed into the amino acid and AMP molecules without the presence of cognate tRNA, whereas in tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing, aa-AMP hydrolysis is triggered by the addition of the cognate tRNA (9–11). Mis-translation due to the impairment or loss of editing activity can lead to ambiguity of the proteome, having a seriously negative effect on the cellular function of most organisms and causing neuron-degeneration in a mouse model (12).

Leucyl-tRNA synthetase (LeuRS) is a large multi-domain class Ia aaRS with both aminoacylation activity to generate Leu-tRNALeu and editing activity to clear non-cognate aa-AMP and aa-tRNA (13). It can be divided into bacterial and archaeal/eukaryotic types based on primary sequence and domain location (14). Both types of LeuRSs usually consist of a Rossmann-fold domain (for amino acid activation and aminoacylation), an α-helix bundle, a C-terminal domain (for tRNA binding) and a CP1 domain (for editing) (15–17). Extensive studies of various LeuRS species all found that non-cognate norvaline (Nva) is the most significantly mis-activated amino acid among all the non-cognate amino acids tested, including Ile, Val, Met and α-amino butyric acid (ABA). For instance, compared with cognate Leu, Nva is mis-activated by Aquifex aeolicus LeuRS (AaLeuRS) (9), Saccharomyces cerevisiae LeuRS (ScLeuRS) (18), human cytoplasmic LeuRS (hcLeuRS) (19), Mycoplasma mobile LeuRS (MmLeuRS) (20), human mitochondrial LeuRS (hmtLeuRS) (unpublished data) 72-, 105-, 100-, 122- and 180-fold less efficiently, respectively. Nva is a non-proteinogenic amino acid differing from Leu only by the absence of a side-chain methyl group. Nva is naturally present in vivo and is a by-product of the Leu biosynthesis pathway (21). Its synthesis is predominantly related to an imbalance in the synthesis of the branched-chain amino acids under pyruvate-high conditions. In addition, Nva significantly accumulates immediately after a shift from aerobic culture conditions to oxygen limitation at high glucose concentrations (22). Therefore, the amount of Nva is dynamic and varies according to the environment. The incorporation of Nva in proteins at Leu codons has been clearly demonstrated. It has been reported to be a natural component of an antifungal peptide of Bacillus subtilis (23) and can be intentionally inserted into heterologous proteins by culturing Escherichia coli in the presence of Nva (US patent, Nov 7, 1989, 4879223). Accompanied by conditions of an elevated ratio of available Nva to Leu in the medium, increasing mis-incorporation of Nva at Leu codons has been observed in recombinant human hemoglobin produced in E. coli as a result of mis-aminoacylation of tRNALeu by E. coli LeuRS (EcLeuRS) (24). It is proposed that Nva replacement may disrupt the correct folding and assembly of hemoglobin and other proteins (24). All this evidence suggests that Nva mis-activation by LeuRS is a non-artificial event that occurs in vivo, and that mis-charged Nva-tRNALeu can be accommodated and used by the ribosome. Therefore, editing of Nva by LeuRS seems to be essential for the correct functioning of organisms.

Based on significant mis-activation of Nva, editing catalyzed by LeuRS (with a functional CP1 domain) has been shown to be one of the most interesting editing mechanisms. This process is predominantly mediated by three diverse pathways (tRNA-independent, tRNA-dependent pre-transfer and post-transfer editing) (10). Both types of LeuRS critically depend on the editing active site embedded in the CP1 domain to perform post-transfer editing (15–17,25). However, MmLeuRS harbors only tRNA-independent pre-transfer editing activity owing to its natural lack of the CP1 domain (20). Another example of a unique LeuRS is hmtLeuRS, which possesses a degenerate editing active site in the CP1 domain as well as defunct post-transfer editing (26) and tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing activities (unpublished data). Combining site-directed mutagenesis and AMP formation methodology, the contribution of different pathways to the overall editing process can be quantified (9,10,19). Strikingly, there are quantitative and species-specific differences in the contribution of a specific pathway to the total editing activity of a LeuRS (9,10,19). To evaluate the significance of each mechanism, we have attempted to generate LeuRSs lacking one or more editing mechanism(s); to date, two types have been successfully established. One type contains LeuRSs with abolished post-transfer editing activity, obtained by introducing mutations at key residues (e.g. EcLeuRS-T252R, AaLeuRS-T273R, AaLeuRS-D373A, ScLeuRS-D419A, hcLeuRS-D399A, Giardia lamblia (Gl) LeuRS-D444A) (9,10,18,19,27) or by the inclusion of a small molecule inhibitor (AN2690) of the CP1 editing domain (10). The second type includes LeuRSs for which both the post-transfer editing and tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing activities (EcLeuRS-Y330D, AaLeuRS-Y358D) have been abolished (10). Our aim was to determine whether a LeuRS with defective tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing activity but intact post-transfer editing would produce mis-charged tRNAs. However, extensive efforts to establish such a LeuRS model failed.

The protein biosynthesis machinery of Candida albicans is of great interest, not only because it is a human pathogen but also in its cytoplasm, the universal Leu codon CUG is translated as both Ser (97%) and Leu (3%) (28,29). This genetic code alteration is mediated by a uniquely evolved tRNA, which bears a CAG anti-codon [C. albicans tRNASer(CAG), CatRNASer] and can be aminoacylated either with Ser by C. albicans seryl-tRNA synthetase (CaSerRS) or with Leu by leucyl-tRNA synthetase (CaLeuRS) (29). Therefore, the proteome of C. albicans is ambiguous with some proteins exhibiting differences in primary sequences. For example, a key player in CUG reassignment, CaSerRS, has two isoforms (SerRS-Leu197 and SerRS-Ser197). The residue at position 197 is located at the SerRS dimer interface, and replacement of Ser by Leu at this site induces a local structural rearrangement, leading to a slightly higher (27%) activity of SerRS-Leu197 compared with SerRS-Ser197 (30). These data indicate that distribution of the CUG codon and its ambiguity is not random and has potential significance. CaLeuRS is another critical molecule in the CUG reassignment in C. albicans, which charges CatRNASer with Leu to produce Leu-CatRNASer. CaLeuRS comprises 1098 residues and has a molecular mass of 126 kDa. A single CUG codon is present at position of 919 of CaLeuRS, which is located at the C-terminal domain. Thus, CaLeuRS should also have two isoforms, CaLeuRS-Ser919 and CaLeuRS-Leu919. Based on the decoding rule of C. albicans (28,29), CaLeuRS exists mainly as CaLeuRS-Ser919 (∼97%), and this was used here as the wild-type form.

In this study, we compared the activity of two LeuRS isoforms and analyzed the cross-species tRNALeu recognition and editing capacity of CaLeuRS. Interestingly, we showed that CaLeuRS is naturally deficient in tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing activity but with obvious tRNA-independent pre-transfer editing and efficient post-transfer editing of Nva. However, it harbored a measurable level of tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing of ABA when specific tRNA was present, although editing of ABA seemed not to be a necessity, as the rejection of ABA was efficient at the aminoacylation active site. Furthermore, post-transfer editing of CaLeuRS was not tRNALeu species-specific but was functional for mis-charged CatRNASer(CAG), being recognized by other eukaryotic LeuRSs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

l-leucine (Leu), l-norvaline (Nva), l-isoleucine (Ile), l-valine (Val), l-methionine (Met), l-serine (Ser), ABA, dithiothreitol (DTT), ATP, CTP, GTP, UTP. 5′-GMP, tetrasodium pyrophosphate, inorganic pyrophosphate, ATP, Tris–HCl, MgCl2, NaCl, yeast total tRNA and activated charcoal were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). [3H]Leu, [32P]tetrasodium pyrophosphate and [α-32P]ATP were obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA, USA). Pfu DNA polymerase, a DNA fragment rapid purification kit and a plasmid extraction kit were purchased from YPH Company (China). The KOD-plus mutagenesis kit was obtained from TOYOBO (Japan). T4 ligase, nuclease S1 and restriction endonucleases were obtained from MBI Fermentas (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase was purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, USA). Ni2+-NTA Superflow was purchased from Qiagen, Inc. (Germany). Polyethyleneimine cellulose plates were purchased from Merck (Germany). Pyrophosphatase (PPiase) was obtained from Roche Applied Science (China). The dNTP mixture was obtained from TaKaRa (Japan). Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by Biosune (China). Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells were purchased from Stratagene (USA).

Gene cloning, mutagenesis and protein expression

The C. albicans genome was kindly provided by Prof. Jiang-Ye Chen of our institute and was used as the template for amplifying genes encoding CaLeuRS, C. albicans SerRS (CaSerRS) and C. albicans mitochondrial LeuRS (CamtLeuRS). Gene sequences of CaLeuRS, CaSerRS and CamtLeuRS were obtained from the Candida Genome Database (http://www.candidagenome.org/). CaLeuRS, CaSerRS and CamtLeuRS genes were cloned into pET28a at the NheI and XhoI sites with N-terminal His6-tag (the mitochondrial targeting sequence of CamtLeuRS had been removed). Plasmids containing EcLeuRS (10), ScLeuRS (18) and Pyrococcus horikoshii LeuRS (PhLeuRS) (31) were constructed previously. The E. coli tRNA(m1G37) methyltransferase (TrmD) gene was amplified from the E. coli genome and inserted between the EcoRI and XhoI of sites of pET28a. The plasmid expressing E. coli tRNA nucleotidyltransferase (CCase) was provided by Dr. Gilbert Eriani (Strasbourg, CNRS, France). Mutation at Asp422 of the CaLeuRS gene was performed with the KOD-plus mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Asp422 corresponds to Asp373, Asp419, Asp444 and Asp399 of AaLeuRS, ScLeuRS, GlLeuRS and hcLeuRS, respectively, which are crucial for post-transfer editing of these LeuRSs (9,10,18,19,27). The CTG and TCG codons at position 919 in the CaLeuRS gene were used to over-express the gene encoding CaLeuRS-Leu919 and CaLeuRS-Ser919, respectively. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. E. coli BL21 (DE3) was transformed with various constructs. A single colony of each of the transformants was chosen and cultured in 500 ml of 2 × YT medium at 37°C. When the cells reached mid-log phase (A600 = 0.6), expression of the recombinant proteins was induced by the addition of 0.2 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside for 8 h at 22°C. Protein purification was performed according to a previously described method (32).

tRNA gene cloning, transcription and methylation

CatRNALeu(UAA) and CatRNASer(CAG) genes were cloned between the PstI and EcoRI sites of pTrc99b with an N-terminal T7 promoter. Detailed T7 in vitro run-off transcription of CatRNALeu and CatRNASer has been described previously (33). The amino acid accepting activities of CatRNALeu(UAA) or CatRNASer(CAG) are 1390 and 1208 pmol/A260, respectively. The methyl group of m1G37 of CatRNASer is a critical element for recognition by LeuRS (29). The purified CatRNASer transcript was methylated at position G37 with E. coli TrmD (34) in a mixture containing 0.1 M Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 6 mM MgC12, 24 mM NH4C1, 7.5 μg of bovine serum albumin, 5 μM CatRNASer transcript, 100 μM S-adenosylmethionine, 1 U/μl RNase inhibitor and 10 μM TrmD at 37°C for 1.5 h. Approximately 45% of transcripts were methylated in this reaction as estimated in a control experiment with 3H-labeled S-adenosylmethionine. m1G37-CatRNASer was ethanol-precipitated at −20°C after phenol/chloroform extraction (twice) and dissolved in 5 mM MgCl2. All CatRNASer used in this study refers to m1G37-CatRNASer. Transcribed or over-expressed E. coli tRNALeu(GAG) (EctRNALeu) and human cytoplasmic tRNALeu(CAG) (hctRNALeu) were obtained according to methods described elsewhere, and their amino acid accepting activity was ∼1500 pmol/A260 (19,35).

32P-labeling of CatRNALeu or CatRNASer

32P-labeling of CatRNALeu or CatRNASer was performed at 37°C in a mixture containing 60 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 12 mM MgCl2, 15 μM CatRNALeu or CatRNASer, 0.5 mM DTT, 15 μM ATP, 50 μM tetrasodium pyrophosphate, 0.666 μM [α-32P]ATP and 10 μM CCase for 5 min. Finally, 0.8 U/μl PPiase was added to the mixture for 2 min. Phenol/chloroform extraction of [32P]CatRNALeu and [32P]CatRNASer was conducted twice, and the product was dissolved in 5 mM MgCl2.

In vitro activity assays

ATP-PPi exchange measurement was carried out at 30°C in a reaction mixture containing 60 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP, 2 mM [32P]tetrasodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM Leu or 50 mM non-cognate ABA, Nva, Val, Ile, Met, Ser and 20 nM CaLeuRS. The kinetics of amino acid activation were measured in the presence of Leu (3–1000 μM) or Nva (0.3–50 mM) or ABA (3–940 mM). Samples of the reaction mixture were removed at specific time-points, added to 200 μl of quenching solution containing 2% activated charcoal, 3.5% HClO4 and 50 mM tetrasodium pyrophosphate and mixed by vortexing for 20 s. The solution was filtered through a Whatman GF/C filter, followed by washing with 20 ml of 10 mM tetrasodium pyrophosphate solution and 10 ml of 100% ethanol. The filters were dried, and [32P]ATP was counted using a scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter).

Aminoacylation of CatRNALeu with Leu was performed in a reaction mixture containing 60 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP, 10 μM CatRNALeu, 20 μM [3H]Leu and 20 nM CaLeuRS at 30°C. The kinetics of CaLeuRS aminoacylation were measured in the presence of CatRNALeu (0.6–15.8 μM) or transcribed or over-expressed EctRNALeu (0.6–10 μM) or yeast total tRNA (0.2–6 μM) or over-expressed hctRNALeu (0.2–6 μM) or transcribed hctRNALeu (0.6–10 μM).

Mis-aminoacylation of [32P]CatRNALeu with Nva or ABA was carried out at 30°C in a reaction mixture containing 60 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP, 5 μM ‘cold’ CatRNALeu, 1 μM [32P]CatRNALeu, 20 mM Nva or 376 mM ABA and 1 μM CaLeuRS or CaLeuRS-D422A. Samples at specific time-points were taken for ethanol precipitation with NaAc (pH 5.2) at −20°C overnight. The precipitated samples were centrifuged (10 000g) at 4°C for 30 min, dried at room temperature for 30 min and digested with 6 μl of nuclease S1 (25 U) for 2 h at 37°C. After treatment with nuclease S1, aminoacyl-[32P]tRNA should produce aminoacyl-[32P]AMP and free [32P]tRNA should produce [32P]AMP. Samples (2 μl) of the digestion mixture were loaded and separated by thin layer chromatography (TLC) in 0.1 M NH4Ac and 5% acetic acid. Known amounts of [α-32P]ATP were diluted and loaded onto the TLC plate for the purposes of quantification. The plates were visualized by phosphorimaging, and the data were analyzed using Multi-Gauge Version 3.0 software (FUJIFILM). Measurement of Nva-[32P]CatRNASer synthesis by CaLeuRS and CaLeuRS-D422A was performed using a similar procedure, except [32P]CatRNASer was used as a substrate. Mis-aminoacylation of [32P]CatRNASer with Leu by various LeuRSs was carried out in a reaction mixture containing 60 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 4 mM ATP, 5 μM ‘cold’ CatRNASer, 1 μM [32P]CatRNASer, 40 mM Leu and 1 μM CaLeuRS, CaLeuRS-D422A, CamtLeuRS, EcLeuRS, ScLeuRS, hcLeuRS and PhLeuRS at 37°C.

Preparation of Nva-[32P]CatRNALeu or Nva-[32P]CatRNASer was carried out with editing-deficient ScLeuRS-D419A or CaLeuRS-D422A, respectively, in a reaction mixture, which was identical to that used for mis-aminoacylation. Post-transfer editing of pre-formed Nva-[32P]CatRNALeu was performed in a reaction mixture containing 60 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 μM Nva-[32P]CatRNALeu and 30 nM CaLeuRS or CaLeuRS-D422A at 30°C. Post-transfer editing of pre-formed Nva-[32P]CatRNASer was performed in a reaction containing 60 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 μM Nva-[32P]CatRNASer and 100 nM CaLeuRS or CaLeuRS-D422A at 30°C. After nuclease S1digestion, the amount of hydrolyzed mis-charged [32P]tRNAs was assayed by TLC according to the procedure described for mis-aminoacylation.

The AMP formation assay was carried out at 30°C in a reaction mixture containing 60 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 10 U/ml PPiase, 15 mM Nva or 350 mM ABA, 3 mM [α-32P]ATP and 0.2 μM CaLeuRS in the presence or absence of 15 μM transcribed CatRNALeu, or 5 μM transcribed or over-expressed EctRNALeu or hctRNALeu. Samples (1.5 µl) were quenched in 6 µl of 200 mM NaAc (pH 5.0). The quenched aliquots (1.5 µl of each sample) were spotted onto polyethyleneimine cellulose plates pre-washed with water. Separation of Nva/ABA-[α-32P]AMP, [α-32P]AMP and [α-32P]ATP was performed in 0.1 M NH4Ac and 5% acetic acid. Quantification of [α-32P]AMP was achieved by densitometry in comparison with [α-32P]ATP samples of known concentrations.

RESULTS

CaLeuRS-Leu919 is more active than CaLeuRS-Ser919

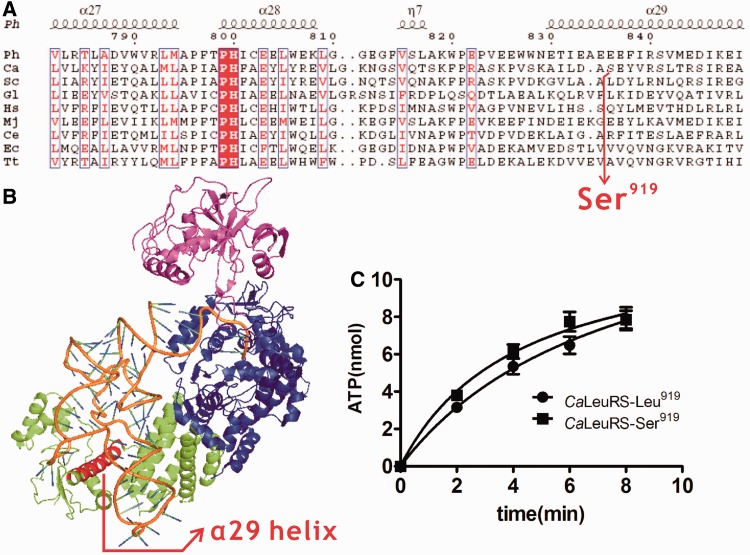

Determination of the crystal structure of the PhLeuRS-tRNALeu complex (Protein Data Bank, PDB 1WZ2) shows that the amino acid at position 919 of archaeal/eukaryotic LeuRSs is located in the α29 helix of the C-terminal domain (Figure 1A and B). The primary sequence of the 919-containing α29 helix is not conserved; thus, it is difficult to identify its homologous site in the crystal structure of PhLeuRS. The CUG codon in E. coli is uniformly translated as Leu. Therefore, we introduced CTG and TCG codons at this position in the CaLeuRS gene to facilitate expression of CaLeuRS-Leu919 and CaLeuRS-Ser919, respectively, in E. coli.

Figure 1.

Location of residue 919 and its effect on amino acid activation in CaLeuRS. (A) Primary sequence alignment of LeuRSs from three domains of life with position of 919 indicated. Amino acid sequences homologous to those from α27 to α29 helix of PhLeuRS are aligned. (B) Crystal structure of PhLeuRS-tRNALeu structure showing the position of 919-containing α29 helix. (C) Amino acid activation measurement of CaLeuRS-Leu919 (black circle) and CaLeuRS-Ser919 (black square). Ph, Pyrococcus horikoshii; Ca, C. albicans; Sc, S. cerevisiae; Gl, Giardia lamblia; Hs, Homo sapiens; Mj, Methanococcus jannaschii; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; Ec, E. coli; Tt, Thermus thermophiles.

No differences were observed in amino acid activation by CaLeuRS-Ser919 and CaLeuRS-Leu919 (Figure 1C), indicating that Leu or Ser insertion at this position has no direct effect on the structure or function of the aminoacylation active site located in the Rossmann-fold domain. This is consistent with the fact that residue 919 is spatially distant from the aminoacylation active site (>50 Å in the PhLeuRS-tRNALeu structure) (Figure 1B). Subsequent comparisons of the aminoacylation kinetics of CaLeuRS-Ser919 and CaLeuRS-Leu919 revealed that CaLeuRS-Leu919 displayed a higher Km (2.91 ± 0.37 μM) and a higher kcat (0.62 ± 0.08 s−1) compared with the values determined for CaLeuRS-Ser919 (Km: 1.87 ± 0.23 μM, kcat: 0.31 ± 0.05 s−1). These data indicated that CaLeuRS-Ser919 has a stronger binding affinity for transcribed CatRNALeu(UAA) during aminoacylation (Table 1). Based on the structure, we suggested that the presence of Ser in this helix may facilitate binding with the variable stem-loop element of CatRNALeu(UAA). The catalytic efficiency of CaLeuRS-Leu919 (213.06 s−1 mM−1) is ∼30% higher than that of CaLeuRS-Ser919 (165.78 s−1 mM−1). This phenomenon is similar to that observed in the case of CaSerRS, for which no differences were observed in the amino acid activation of CaSerRS-Leu197 and CaSerRS-Ser197, whereas CaSerRS-Leu197 showed a slightly (27%) higher activity than CaSerRS-Ser197(30).

Table 1.

Aminoacylation kinetic parameters of CaLeuRS-Ser919 and CaLeuRS-Leu919 for the CatRNALeu transcripta

| Enzyme | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) | Relative kcat/Km |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaLeuRS-Ser919 | 1.87 ± 0.23 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 165.78 | 1.0 |

| CaLeuRS-Leu919 | 2.91 ± 0.37 | 0.62 ± 0.08 | 213.06 | 1.3 |

aThe results are the average of three independent repeats with standard deviations indicated.

According to the decoding rule of C. albicans, CaLeuRS is present in the cytoplasm mainly in the form of CaLeuRS-Ser919. Thus, in the following study, we used CaLeuRS-Ser919 as the wild-type CaLeuRS.

Yeast LeuRSs efficiently recognized bacterial, yeast and human tRNALeus

Species-specific charging of tRNA is common for some aaRSs systems. The aaRSs from higher organisms often have the capacity to charge tRNA from lower species, whereas aaRSs from lower organisms fail to aminoacylate tRNA from higher ones. It is unclear whether yeast LeuRS is able to recognize various tRNALeus from other species. In this study, we investigated the tRNALeu recognition capacity in detail using CaLeuRS as a model system.

The CatRNALeu gene could not be over-expressed in E. coli and was obtained by T7 in vitro transcription. We also obtained transcribed and over-expressed EctRNALeu and hctRNALeu to reveal any potential role of base modification in recognition. Moreover, as transcribed S. cerevisiae tRNALeu without modification showed no Leu accepting activity (data not shown), commercial S. cerevisiae yeast total tRNA was used.

CaLeuRS recognized all the available tRNAs. It aminoacylated transcribed or over-expressed EctRNALeu with similar kcat values (0.474 ± 0.026 and 0.555 ± 0.061 s−1, respectively), although the Km for transcribed EctRNALeu (2.68 ± 0.39 μM) was nearly 4-fold greater than that for over-expressed EctRNALeu (0.74 ± 0.08 μM). Interestingly, CaLeuRS efficiently charged both transcribed and over-expressed hctRNALeu, which was from a higher organism. A similar recognition pattern as seen with the two EctRNALeus was also observed, with comparable kcat values but a smaller Km for over-expressed hctRNALeu, indicating base modification was important for tRNA recognition. Additionally, CaLeuRS obviously charged yeast total tRNA with Km and kcat values of 0.39 ± 0.05 μM and 0.174 ± 0.019 s−1, respectively, and with the greatest catalytic efficiency (1486.05 s−1 mM−1) for over-expressed hctRNALeu among all the tested tRNAs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Aminoacylation kinetic parameters of CaLeuRS and ScLeuRS for various tRNAsa

| Enzyme | tRNA | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaLeuRS | OEb-EctRNALeu | 0.74 ± 0.08 | 0.474 ± 0.026 | 640.54 |

| TSc-EctRNALeu | 2.68 ± 0.39 | 0.555 ± 0.061 | 207.09 | |

| yeast total tRNA | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 0.174 ± 0.019 | 446.15 | |

| OE-hctRNALeu | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 0.639 ± 0.055 | 1486.05 | |

| TS-hctRNALeu | 1.30 ± 0.23 | 0.719 ± 0.094 | 553.08 | |

| ScLeuRS | OE-EctRNALeu | 2.19 ± 0.47 | 2.09 ± 0.16 | 954.34 |

| TS-EctRNALeu | 1.71 ± 0.22 | 0.134 ± 0.011 | 78.36 | |

| yeast total tRNA | 0.332 ± 0.037 | 0.188 ± 0.025 | 566.27 | |

| OE-hctRNALeu | 0.111 ± 0.027 | 2.19 ± 0.22 | 19 729.73 | |

| TS-hctRNALeu | 0.926 ± 0.170 | 0.887 ± 0.114 | 957.88 |

aThe results are the average of three independent repeats with standard deviations indicated.

bOE, over-expressed.

cTS, transcribed.

Owing to recognition ability of CaLeuRS for hctRNALeu, we further explored the capacity of ScLeuRS to aminoacylate bacterial and human tRNALeus as well as yeast tRNA. ScLeuRS aminoacylated yeast total tRNA with Km and kcat values of 0.332 ± 0.037 μM and 0.188 ± 0.025 s−1, respectively. However, its kcat values for over-expressed EctRNALeu or hctRNALeu increased >10-fold (2.09 ± 0.16 and 2.19 ± 0.22 s−1, respectively), although the Km values differed from each other remarkably (2.19 ± 0.47 μM for over-expressed EctRNALeu and 0.111 ± 0.027 μM for over-expressed hctRNALeu). These data demonstrated that over-expressed hctRNALeu was the best aminoacylation substrate for ScLeuRS (catalytic efficiency 19 729.73 s−1 mM−1) and furthermore suggested that base modification was important during recognition or catalysis. ScLeuRS recognized transcribed EctRNALeu with a similar Km (1.71 ± 0.22 μM) but a sharply decreased kcat (0.134 ± 0.011 s−1) compared with the values of over-expressed EctRNALeu. It also recognized transcribed hctRNALeu with an increased Km (0.926 ± 0.170 μM) and a decreased kcat (0.887 ± 0.114 s−1) compared with the values for over-expressed hctRNALeu (Table 2).

Overall, both CaLeuRS and ScLeuRS recognized bacterial, yeast and human tRNALeus. Interestingly, recognition of CatRNALeu by hcLeuRS was negligible (Supplementary Figure S1A). Futhermore, EcLeuRS failed to acylate CatRNALeu (Supplementary Figure S1B). These results were unexpected because it is widely accepted that aaRSs from higher organisms are able to aminoacylate tRNAs from lower organisms.

Amino acid activation capacity of CaLeuRS

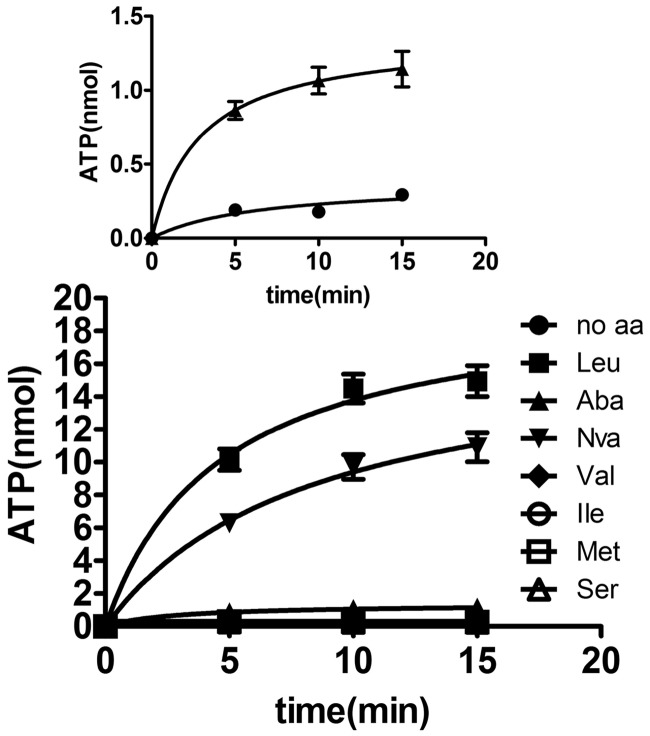

Various LeuRSs have been shown to mis-activate a series of non-cognate amino acids. To investigate mis-activation of non-cognate amino acids by CaLeuRS, we included ABA, Nva, Val, Ile, Met, Ser in the ATP-PPi exchange reaction. The data clearly showed that CaLeuRS significantly mis-activated Nva; furthermore, ABA was also mis-activated to an obvious level compared with the control reaction conducted in the absence of amino acids. In contrast, mis-activation of Val, Ile, Met and Ser was comparable with that of the control reaction conducted in the absence of amino acids (Figure 2). To further define the quantitative discrimination capacity of the aminoacylation active site of CaLeuRS, we measured the activation kinetics for cognate Leu and non-cognate Nva and ABA of CaLeuRS. CaLeuRS gave much higher Km values for Nva (5487 ± 645 μM) and ABA (120387 ± 1698 μM); however, the kcat values were comparable with that for Leu, equating to discriminator factors for Nva and ABA of 220 and 3462, respectively (Table 3). These results indicated that Nva is a real challenge for CaLeuRS and that removal of Nva-AMP and/or Nva-tRNALeu is required to maintain the translational quality control. However, the discrimination against ABA was below the proposed threshold of 1/3000, indicating that editing of ABA may not be necessary.

Figure 2.

Amino acid activation properties of CaLeuRS. Activation of Leu (black square), ABA (black up-pointing triangle), Nva (black down-pointing triangle), Val (black diamond), Ile (white circle), Met (white square) and Ser (white up-pointing triangle) by CaLeuRS. Leu and non-cognate amino acids were used at final concentrations of 1 and 50 mM, respectively. A control reaction without any amino acids (black circle) was included. The insert compares the activation of ABA and the control.

Table 3.

Amino acid activation kinetics of CaLeuRS for various amino acidsa

| Amino acid | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Km (s−1 mM−1) | Discrimination factorb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leu | 40.11 ± 3.84 | 93.05 ± 10.25 | 2319.87 | 1 |

| Nva | 5487 ± 645 | 57.77 ± 6.35 | 10.53 | 220 |

| ABA | 12 0387 ± 1698 | 80.28 ± 10.75 | 0.67 | 3462 |

aThe results are the average of three independent repeats with standard deviations indicated.

bDiscrimination factor corresponds to the loss of catalytic efficiency relative to Leu.

CaLeuRS exhibited little tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing for Nva

The hydrolysis of Nva-AMP or Nva-tRNALeu may be separately or simultaneously catalyzed by CaLeuRS. Editing leads to the net consumption of ATP (yielding AMP) due to repetitive cycles of synthesis-hydrolysis of the non-cognate products. This is the basis of the TLC-based AMP formation methodology, in which the editing capacity is measured by monitoring the quantity of AMP produced (9–11,36,37). In the presence of tRNA and non-cognate amino acid, the TLC assay measures the global editing activity, including the tRNA-independent and tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing in addition to the post-transfer editing. In the absence of tRNA, but with non-cognate amino acid, AMP is produced only from tRNA-independent pre-transfer editing activity (10).

We initially assayed Nva-included AMP formation by CaLeuRS with or without the CatRNALeu transcript. CaLeuRS showed similar observed rate constants (kobs) with (0.28 ± 0.04 s−1) or without (0.25 ± 0.03 s−1) CatRNALeu, indicating that CaLeuRS possesses little tRNA-dependent editing capability (Table 4). To reveal any effect of the residue at position 919, we also determined the editing capacity of CaLeuRS-Leu919 and obtained comparable kobs values in the absence (0.22 ± 0.02 s−1) and presence (0.25 ± 0.05 s−1) of the CatRNALeu transcript. These data suggested that CaLeuRS possesses negligible CatRNALeu-dependent editing capability. It is also possible that modified bases of tRNALeu play a crucial role in Nva-editing. However, the lack of availability of over-expressed CatRNALeu impeded exploration of the potential role of modified bases in editing. Therefore, we performed AMP formation assays with Nva in the presence of transcribed or over-produced EctRNALeu in E. coli, which could be leucylated by CaLeuRS. In accordance with our findings, the kobs values with unmodified or modified EctRNALeu were 0.40 ± 0.06 or 0.51 ± 0.04 s−1, respectively. Similarly, transcribed or over-produced hctRNALeu in E. coli, both of which were effectively aminoacylated by CaLeuRS, stimulated Nva-editing of CaLeuRS with kobs values of 0.33 ± 0.02 or 0.38 ± 0.05 s−1, respectively (Table 4). These data showed that the modified bases of tRNALeu had little effect on the tRNA-dependent editing of CaLeuRS. Based on data from various transcripts or the tRNALeu with modified bases, we concluded that CaLeuRS has little tRNA-dependent editing activity for Nva. Whether it was deficient in post-transfer editing would be explored later in the text. By comparing the kobs values with or without tRNAs, we also observed that post-transfer editing, if it occurred, contributed little to the total editing, and that the observed kobs with tRNAs was almost a reflection of the tRNA-independent pre-transfer editing.

Table 4.

kobs values of CaLeuRSs for editing Nva with various tRNAs

| Enzyme | tRNA | kobs (s−1)a |

|---|---|---|

| CaLeuRS | No tRNA | 0.25 ± 0.03 |

| CatRNALeu | 0.28 ± 0.04 | |

| TSb-EctRNALeu | 0.40 ± 0.06 | |

| OEc-EctRNALeu | 0.51 ± 0.04 | |

| TS-hctRNALeu | 0.33 ± 0.02 | |

| OE-hctRNALeu | 0.38 ± 0.05 | |

| CaLeuRS-D422A | No tRNA | 0.22 ± 0.06 |

| OE-hctRNALeu | 0.25 ± 0.04 | |

| CaLeuRS-Leu919 | No tRNA | 0.22 ± 0.02 |

| CatRNALeu | 0.25 ± 0.05 |

aThe results are the average of three independent repeats with standard deviations indicated.

bTS, transcribed.

cOE, over-expressed.

CaLeuRS exhibited obvious and efficient post-transfer editing to prevent synthesis of Nva-tRNALeu

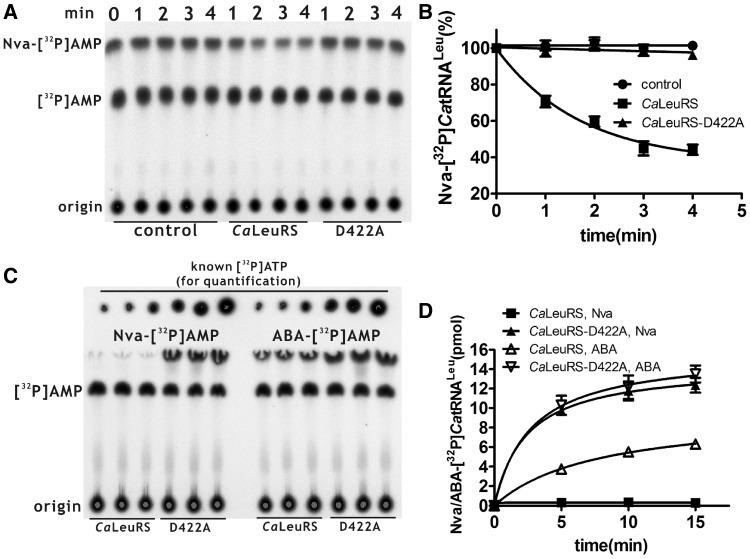

The absence of significant stimulation of editing of Nva by CaLeuRS with various tRNALeus prompted us to investigate its post-transfer editing capability. Usually, the post-transfer editing ability of various LeuRSs is monitored by hydrolysis of Ile- or Met-tRNALeu, which are easily obtained by mis-charging tRNALeu with commercially available radioactive Ile or Met using a LeuRS mutant without post-transfer editing capability. Because we focused on the Nva-editing properties of CaLeuRS and Nva labeled with radioactive isotope was not commercially available, the 3′ end of CatRNALeu was first labeled with [α-32P]ATP by E. coli CCase, and then Nva-[32P]CatRNALeu was prepared by editing-deficient ScLeuRS-D419A (13,18). Hydrolytic analysis clearly showed that CaLeuRS edited Nva-[32P]CatRNALeu when compared with the control experiment conducted in the absence of the enzyme (Figure 3A and B). To confirm the post-transfer editing reaction catalyzed by CaLeuRS, we mutated the conserved and post-transfer editing-essential Asp422 to generate CaLeuRS-D422A. Asp422 corresponds to Asp373, Asp419, Asp444 and Asp399 of AaLeuRS, ScLeuRS, GlLeuRS and hcLeuRS, respectively, which are crucial to post-transfer editing by these LeuRSs (9,10,18,19,27). Indeed, CaLeuRS-D422A did not hydrolyze Nva-[32P]CatRNALeu and was deficient in post-transfer editing, indicating that this mutation inactivated the CP1 domain of CaLeuRS (Figure 3A and B). Further mis-aminoacylation of [32P]CatRNALeu with Nva showed that a significant amount of Nva-[32P]CatRNALeu was formed by CaLeuRS-D422A; however, a negligible amount of mis-charged CatRNALeu was formed by CaLeuRS (Figure 3C and D). Overall, these data showed that CaLeuRS harbored an obvious and efficient capability for post-transfer editing of Nva-[32P]CatRNALeu, the loss of which caused accumulation of mis-charged tRNALeu. No further accumulation of AMP after the addition of CatRNALeu in the AMP formation assay (Table 4) suggested that post-transfer editing of mis-charged CatRNALeu contributed little to the total editing. To further explore the absence of tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing of Nva by CaLeuRS, we tested the AMP formation of CaLeuRS-D422A in the presence of Nva with or without over-produced hctRNALeu. The data showed that over-produced hctRNALeu with modified bases did not stimulate further AMP production after abolishing post-transfer editing (kobs 0.22 ± 0.06 versus 0.25 ± 0.04 s−1), confirming the lack of tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing of Nva by CaLeuRS (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Post-transfer editing and mis-aminoacylation of CatRNALeu by CaLeuRS and CaLeuRS-D422A. (A) A representative graph showing hydrolysis of Nva-[32P]CatRNALeu by CaLeuRS and CaLeuRS-D422A. Nuclease S1-generated Nva-[32P]AMP (reflecting Nva-[32P]CatRNALeu) and [32P]AMP (reflecting free [32P]CatRNALeu) were separated by TLC. A control reaction represented the spontaneous hydrolysis of Nva-[32P]CatRNALeu without the addition of enzyme. (B) Analysis of post-transfer editing of Nva-[32P]CatRNALeu in (A). (C) A representative graph showing mis-charging of [32P]CatRNALeu with non-cognate Nva (left) or ABA (right). Free [32P]CatRNALeu and mis-charged [32P]CatRNALeu are represented by [32P]AMP and Nva-[32P]AMP or ABA-[32P]AMP, respectively. Known amounts of [α-32P]ATP were serially diluted and loaded onto the TLC plate after separation for quantification. (D) Quantitative analysis of Nva-[32P]CatRNALeu or ABA-[32P]CatRNALeu generated by CaLeuRS (black square) and CaLeuRS-D422A (black up-pointing triangle) or ABA-[32P]CatRNALeu by CaLeuRS (white up-pointing triangle) and CaLeuRS-D422A (white down-pointing triangle) in (C).

CaLeuRS inhibited synthesis of Nva-tRNASer by non tRNA species-specific post-transfer editing

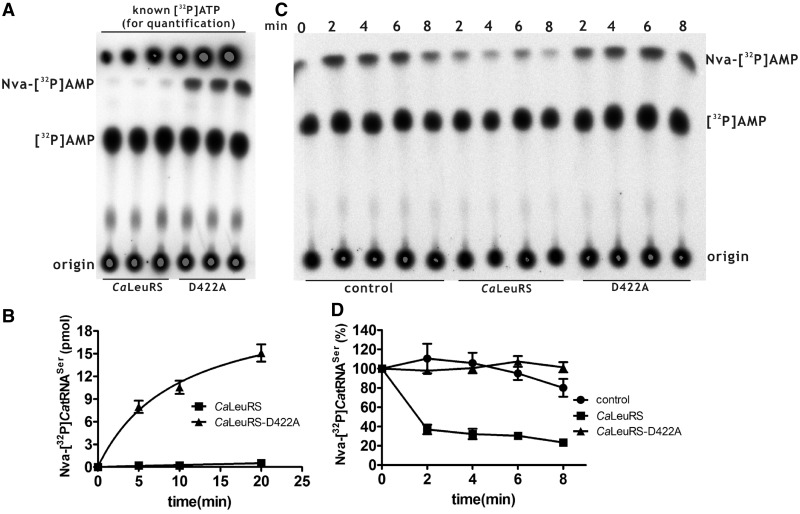

The ability of CaLeuRS to efficiently mis-activate non-cognate Nva and recognize non-cognate CatRNASer raises the interesting question of how to prevent the formation of Nva-CatRNASer. To test for the presence of post-transfer editing activity that hydrolyzes potentially synthesized Nva-CatRNASer, mis-aminoacylation of [32P]CatRNASer with Nva by CaLeuRS was compared with that of the post-transfer editing-deficient CaLeuRS-D422A. The data clearly showed that, mutation of Asp422 resulted in significant synthesis of Nva-[32P]CatRNASer by the mutant, in contrast to wild-type enzyme, which generated negligible amounts of Nva-[32P]CatRNASer, indicating that CaLeuRS used post-transfer editing to prevent Nva-CatRNASer synthesis (Figure 4A and B). We then prepared Nva-CatRNASer for use in hydrolysis assays to more directly monitor the post-transfer editing activity. Obvious hydrolysis of Nva-[32P]CatRNASer was mediated by CaLeuRS but not CaLeuRS-D422A (Figure 4C and D). Above all, these data showed that the post-transfer editing by CaLeuRS was not only CatRNALeu specific but also efficient for CatRNASer to inhibit synthesis of both Nva-CatRNALeu and Nva-CatRNASer.

Figure 4.

Mis-charging of [32P]CatRNASer with Nva and post-transfer editing of Nva-[32P] CatRNASer by CaLeuRS and CaLeuRS-D422A. (A) A representative graph showing mis-charging of [32P]CatRNASer with non-cognate Nva. Free [32P]CatRNASer and mis-charged [32P]CatRNASer are represented by [32P]AMP and Nva-[32P]AMP after digestion of nuclease S1. Known amounts of [α-32P]ATP were serially diluted and loaded onto the TLC plate after separation for quantification. (B) Quantitative analysis of Nva-[32P] CatRNASer generated by CaLeuRS (black square) and CaLeuRS-D422A (black up-pointing triangle) in (A). (C) A representative graph showing hydrolysis of Nva-[32P]CatRNASer by CaLeuRS and CaLeuRS-D422A. A control reaction represented the spontaneous hydrolysis of Nva-[32P]CatRNASer without the addition of enzyme. (D) Analysis of post-transfer editing of Nva-[32P]CatRNASer by CaLeuRS (black square) and CaLeuRS-D422A (black up-pointing triangle) in (C).

CaLeuRS possessed weak tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing capacity for ABA

ABA was selected to test whether CaLeuRS possessed any tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing of other non-cognate amino acids because it was obviously activated by CaLeuRS. CatRNALeu transcript, transcribed or over-produced EctRNALeu and hctRNALeu were used to trigger editing of ABA by CaLeuRS (Table 5). The data showed that over-produced hctRNALeu obviously stimulated editing by increasing the kobs 5-fold [(23.19 ± 3.62) × 10−3 s−1] compared with that in the absence of tRNA [(4.69 ± 0.51) × 10−3 s−1]. Over-expressed EctRNALeu led only to an ∼3-fold increase in kobs [(14.58 ± 2.14) × 10−3 s−1]. However, CatRNALeu, EctRNALeu and hctRNALeu transcripts had little effect on the rate of ABA-editing (Table 5). These data implied that editing of ABA was tRNA modification-dependent. As over-produced hctRNALeu was the most efficient stimulator of ABA-editing, we measured AMP formation by the editing-deficient CaLeuRS-D422A mutant in the presence of ABA with over-produced hctRNALeu. Mutation of Asp422, which abolished post-transfer editing, apparently decreased the rate of AMP formation with a kobs of (12.16 ± 1.98) × 10−3 s−1. Therefore, with over-produced hctRNALeu, post-transfer editing of ABA by CaLeuRS accounted for 47.6% of the total editing [(23.19 − 12.16)/23.19], whereas tRNA-independent and tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing of ABA only accounted for 20.2% (4.69/23.19) and 32.2% [(12.16 − 4.69)/23.19], respectively, of the total editing of ABA by CaLeuRS.

Table 5.

kobs values of CaLeuRSs for editing ABA with various tRNAs

| Enzyme | tRNA | kobs (×103) (s−1)a |

|---|---|---|

| CaLeuRS | No tRNA | 4.69 ± 0.51 |

| CatRNALeu | 4.90 ± 0.37 | |

| TSb-EctRNALeu | 4.78 ± 0.26 | |

| OEc-EctRNALeu | 14.58 ± 2.14 | |

| TS-hctRNALeu | 10.93 ± 0.85 | |

| OE-hctRNALeu | 23.19 ± 3.62 | |

| CaLeuRS-D422A | OE-hctRNALeu | 12.16 ± 1.98 |

aThe results are the average of three independent repeats with standard deviations indicated.

bTS, transcribed.

cOE, over-expressed.

We further performed aminoacylation of [32P]CatRNALeu by CaLeuRS and CaLeuRS-D422A with saturating concentrations of ABA. The data showed that defective post-transfer editing resulted in the generation of significantly more ABA-[32P]CatRNALeu; however, surprisingly, even CaLeuRS yielded a significant amount of ABA-[32P]CatRNALeu (Figure 3C and D). These data implied that editing of ABA by CaLeuRS was not sufficient to prevent the synthesis of ABA-[32P]CatRNALeu in the presence of saturating ABA concentrations. This paradox between ABA mis-aminoacylation and charging accuracy may be solved by fine discrimination against ABA at the aminoacylation active site (Table 3).

These results revealed that CaLeuRS exhibits a weak level of tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing activity for ABA. In addition, the total ABA-editing capacity is not sufficient to avoid the formation of mis-charged tRNALeu, which is different from Nva-editing capacity.

ScLeuRS, like CaLeuRS, also exhibited little tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing capacity for Nva

The natural deficiency in tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing of Nva by CaLeuRS prompted us to investigate whether it is a common characteristic of other yeast LeuRS. Therefore, we assayed the Nva-included AMP formation catalyzed by ScLeuRS in the absence or presence various tRNALeus. The data showed that over-produced hctRNALeu obviously stimulated editing (kobs of 0.64 ± 0.04 s−1) compared with that observed in the absence of tRNA (0.10 ± 0.02 s−1). However, transcribed CatRNALeu, EctRNALeu, hctRNALeu and over-expressed EctRNALeu failed to trigger further editing by ScLeuRS (Table 6). The formation of AMP stimulated by tRNALeu should be derived from tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing and/or post-transfer editing. To distinguish between these two pathways, the conserved Asp419 was mutated to generate ScLeuRS-D419A, which has been shown to be defective in post-transfer editing and is homologous with Asp422 of CaLeuRS (13,18). Assay of the Nva-included AMP formation by ScLeuRS-D419A showed that the kobs with over-produced hctRNALeu was only slightly greater (0.100 ± 0.010 s−1) than that observed in the absence of tRNA (0.094 ± 0.001 s−1), indicating that inactivation of post-transfer editing totally abolished the triggering of AMP formation by tRNA, and that the increase in AMP production by over-produced hctRNALeu was due to post-transfer editing. Therefore, like CaLeuRS, ScLeuRS did not significantly catalyze tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing for Nva.

Table 6.

kobs values of ScLeuRSs for editing Nva with various tRNAs

| Enzyme | tRNA | kobs (s−1)a |

|---|---|---|

| ScLeuRS | no tRNA | 0.10 ± 0.02 |

| TSb-EctRNALeu | 0.10 ± 0.02 | |

| OEc-EctRNALeu | 0.12 ± 0.03 | |

| CatRNALeu | 0.10 ± 0.03 | |

| TS-hctRNALeu | 0.10 ± 0.01 | |

| OE-hctRNALeu | 0.64 ± 0.04 | |

| ScLeuRS-D419A | no tRNA | 0.094 ± 0.001 |

| OE-hctRNALeu | 0.100 ± 0.010 |

aThe results are the average of three independent repeats with standard deviations indicated.

bTS, transcribed.

cOE, over-expressed.

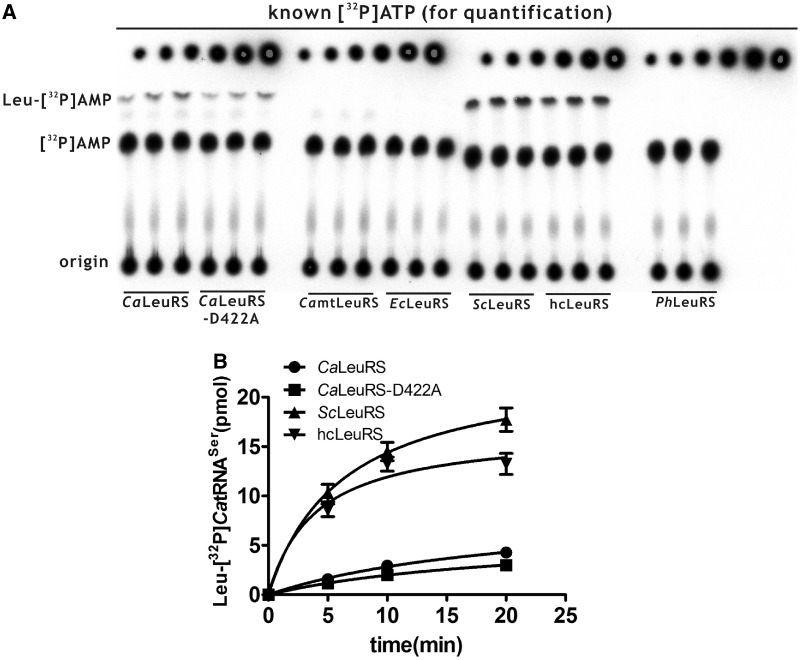

Eukaryotic, but not archaeal or bacterial LeuRSs, recognized CatRNASer

It is interesting that LeuRSs from some Candida species recognize a uniquely evolved tRNASer to introduce ambiguity at CUG codons (28). Unfortunately, no elements of CaLeuRS have been identified to account for the interaction with anti-codon stem and/or loop of CatRNASer. To test whether other eukaryotic, archaeal, bacterial or mitochondrial LeuRSs could potentially recognize CatRNASer, we performed aminoacylation of [32P]CatRNASer with Leu by CamtLeuRS, EcLeuRS, ScLeuRS, hcLeuRS and PhLeuRS. The data showed that only eukaryotic LeuRSs (including CaLeuRS, ScLeuRS and hcLeuRS) could aminoacylate CatRNASer with Leu; however, other LeuRSs, including bacterial EcLeuRS, mitochondrial CamtLeuRS and archaeal PhLeuRS, failed to charge it (Figure 5). Strikingly, under the same conditions, ScLeuRS and hcLeuRS mediated more efficient aminoacylation of CatRNASer.

Figure 5.

Recognition of CatRNASer by representative bacterial, yeast, human and archaeal LeuRSs. (A) A representative graph showing aminoacylation of [32P]CatRNALeu with Leu by various LeuRSs. The generated Leu-[32P]CatRNALeu or free [32P]CatRNALeu was separated by TLC. Known amounts of [α-32P]ATP were serially diluted and loaded onto the TLC plate after separation for quantification. (B) Quantitative analysis of Leu-[32P]CatRNASer generated by CaLeuRS (black circle), CaLeuRS-D422A (black square), ScLeuRS (black up-pointing triangle) and hcLeuRS (black down-pointing triangle). No charged [32P]CatRNASer was catalyzed by CamtLeuRS, EcLeuRS and PhLeuRS.

DISCUSSION

Insertion of Ser or Leu at CUG codons might not be incidental

In C. albicans and most other CUG clade species, a mutant tRNASer(CAG) has evolved to decode the Leu CUG codon both as Ser and Leu (28,29). This peculiarity is derived from its combined tRNALeu and tRNASer identity elements (38). This tRNA is mainly aminoacylated by SerRS and charged by LeuRS to a small extent (29). Both biochemical and structural data have revealed that ambiguity at the single CUG codon of SerRS induces local structural rearrangement, leading to a slightly increased activity (27%) of CaSerRS-Leu197 compared with the wild-type CaSerRS-Ser197 (30). Furthermore, genetic studies showed that increased Leu incorporation across all the CUG codons of C. albicans had no visible effect on the growth phenotype but had an impressive impact on cell morphology (39). Therefore, it was proposed that CUG decoding ambiguity has a potential regulatory role in protein structure and/or function (30). CaLeuRS is another crucial player in this genetic code alteration and also contains only one CUG codon at position 919. This site is located at the C-terminal domain of LeuRS, which has been shown to be responsible for binding the variable loop of tRNALeu and involved in the aminoacylation activity; however, this domain is not strictly conserved among archaeal/eukaryotic LeuRSs (Figure 1A and B). Here, we revealed that both CaLeuRS-Leu919 and CaLeuRS-Ser919 catalyzed Leu activation and aminoacylation, but the former was more active (30%) than the latter, indicating that the conformation of the 919-containing α29 helix might be finely controlled by the introduction of either Ser or Leu. This phenomenon was also observed in another crucial player in the CUG decoding alteration pathway, CaSerRS (30). We suggested that insertion of either Ser or Leu at the CUG codon was not random and incidental. The relative amounts of CaLeuRS-Ser919/CaLeuRS-Leu919 should be strictly regulated by an unidentified but precise molecular mechanism in vivo. Whether the fine balance of CaLeuRS-Ser919/CaLeuRS-Leu919 is critical for decoding other Leu codons and correlates with the ratio of CaSerRS-Ser197/CaSerRS-Leu197 requires further investigation.

Yeast LeuRS exhibited a relaxed tRNA recognition capacity

In tRNA aminoacylation, species-specific charging, where a tRNA from one taxonomic domain is not aminoacylated by an aaRS from another, is widespread. This may be as a result of the co-evolution of synthetase/tRNA pairs by the addition of species-specific elements. For instance, human tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase does not recognize bacterial tRNATyr, and E. coli tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase is unable to charge eukaryotic tRNATyr (40), and there is no cross-recognition of E. coli and human tRNAGly by the respective glycyl-tRNA synthetases (41). Similarly, E. coli isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase is unable to charge eukaryotic tRNAIle (42). Yeast ArgRS charges E. coli tRNAArg; however, E. coli ArgRS acylates only its cognate E. coli tRNA (43). Human cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase charges bacterial tRNACys, but E. coli cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase is non-functional in aminoacylating human tRNATyr (44). Here, we showed that both hcLeuRS and EcLeuRS failed to aminoacylate CatRNALeu; however, both CaLeuRS and ScLeuRS readily aminoacylated bacterial, yeast and even human tRNALeus. These results showed that yeast LeuRSs exhibit a more relaxed recognition specificity compared with other LeuRSs. Indeed, CatRNASer itself harbors only tRNALeu recognition elements in the anti-codon loop with other parts being crucial for SerRS recognition. In addition, G33 is also unfavorable for LeuRS; even in this adverse state, CaLeuRS aminoacylates it in vivo (29). Comparison between transcribed and over-expressed tRNALeus showed that base modification of tRNALeu plays an important role in both binding and catalysis.

CaLeuRS was deficient in tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing but exhibited efficient post-transfer editing for Nva

Nva is inherently mis-activated by various LeuRSs to a significant level that requires editing for translational accuracy (9,18–20). With an elevated ratio of Nva to Leu, Nva can escape the safeguarding of EcLeuRS and replace Leu in proteins rich in Leu codons, indicating that Nva-tRNALeu can escape further checking by the ribosome and pose a direct threat to the accuracy of newly synthesized proteins (24). From the viewpoint of editing, some LeuRSs with degenerated (e.g. hmtLeuRS) or deleted CP1 (e.g. MmLeuRS) domains are exceptional examples, which use alternative pathways (efficient discrimination at the active site) for translational quality control (hmtLeuRS) (26) or do not edit mis-aminoacylation product to produce proteome ambiguity (MmLeuRS) (20). However, all LeuRSs with functional CP1 domains studied so far display tRNA-independent, tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing and post-transfer editing for Nva. Through inactivation of CP1 or utilization of LeuRS inhibitors, post-transfer editing has been successfully isolated (9,10,18,19,27). Similarly, by mutating a crucial Tyr residue to Asp in EcLeuRS and AaLeuRS, both tRNA-dependent pre-transfer and post-transfer editing are inactivated (10,33). Interestingly, this study identified that CaLeuRS itself is naturally defective in tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing for Nva. With CatRNALeu, no tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing was identified. In contrast, weak tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing for ABA in the presence of specific tRNALeu was observed, despite the indication that ABA-editing might not be necessary in vivo based on fine discrimination at the active site. Similarly, ScLeuRS did not mediate tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing. These results indicate that the capacity for tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing for Nva has been lost by CaLeuRS (also ScLeuRS), and that ABA is also rarely induced. The reason for this deficiency in tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing and the pathway by which this deficiency was introduced remains to be elucidated.

Post-transfer editing contributed little or negligibly to the total Nva-editing since addition of any tRNAs in the AMP formation assays did not significantly induce additional AMP. Thus, the produced AMP was mainly derived from tRNA-independent pre-transfer editing. However, the energy-saving post-transfer editing pathway critically controls the accuracy of aminoacylation. Mutation at the conserved Asp422 of CaLeuRS led to a LeuRS with abolished post-transfer editing capacity; consequently, Nva-tRNALeu was synthesized. Similarly, ScLeuRS did not synthesize Ile-tRNALeu; however, ScLeuRS-D419A readily generated significant amounts of Ile-tRNALeu (13,18). Using these unique CaLeuRS and ScLeuRS models devoid of tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing capacity, we concluded that the post-transfer editing pathway is the most economic but efficient editing mechanism for LeuRS. Consistent with other LeuRS models and even other aaRS systems, once post-transfer editing is impaired, the mis-charged tRNA is unavoidably accumulated (9–11,18,19,27,45,46).

Our results also revealed that post-transfer editing by CaLeuRS is not tRNA-species specific, as Nva-CatRNASer was also a substrate. Indeed, based on the poor discrimination against Nva in the active site, Nva-tRNASer is possibly synthesized but should be removed. Otherwise, the CUG codon might be decoded as Ser, Leu and Nva in vivo. It has been proposed that the acceptor end of the tRNA switches from a hairpin conformation to a helical conformation for editing by class I aaRSs, whereas the reverse change in conformation occurs at the acceptor end of the tRNA for editing by class II aaRSs (47). Notably, CatRNASer corresponds to a class II SerRS; however, results here showed that CatRNASer could switch from a hairpin to a helical conformation for editing by a class I LeuRS.

Eukaryotic LeuRSs recognized CatRNASer

In addition, we revealed that other eukaryotic LeuRSs could efficiently aminoacylate CatRNASer, implying that the introduction or evolution of this type of tRNA in other eukaryotic systems would reprogram or discombobulate the genetic code, leading to proteome chaos. In other words, a specific eukaryotic genetic code could be artificially reprogramed by expression of this tRNASer. Indeed, CatRNASer has been shown to be efficiently produced, processed and aminoacylated in S. cerevisiae, with its expression triggering a stress response, blocking mating and re-defining the gene expression model of S. cerevisiae (48). Notably, archaeal LeuRS is in the same group with eukaryotic LeuRS according to primary or higher structure (14) and only differs at the C-terminal tRNA binding domain, indicating that this domain in eukaryotic LeuRSs is a key element for recognition of CatRNASer. This observation is consistent with the structural and biochemical results showing that the C-terminal domain of archaeal LeuRS specifically contacts the variable loop but not the anti-codon loop of archaeal tRNALeu (16,49). However, the anti-codon loop, which is a key recognition element in both CatRNASer (28,29,38) and yeast tRNALeu (49), is likely to be bound by the C-terminal domain of eukaryotic LeuRS. This proposal requires confirmation from eukaryotic LeuRS-tRNALeu/tRNASer structures.

Concluding remarks

Translational machinery of human pathogen C. albicans is of particular interest because its CUG codon in the genome is decoded as both Ser and Leu by a unique CatRNASer, leading to proteome ambiguity (28,29). One of the most crucial components in this decoding process is CaLeuRS, which catalyzes two successive steps, aminoacylation and editing reactions, which together are essential for ensuring high specificity of tRNA charging. In aminoacylation, we showed that Leu isoform was more active than Ser isoform of CaLeuRS in charging CatRNALeu, implying the existence of an in vivo mechanism regulated by balance of CaLeuRS-Leu919 and CaLeuRS-Ser919. In addition, as a yeast LeuRS model, CaLeuRS recognized tRNALeus from bacteria, yeast and higher eukaryote. In editing, CaLeuRS efficiently mis-activated non-cognate Nva. One of the most interesting findings was that CaLeuRS lacked tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing for Nva, which has been well investigated for bacterial and human LeuRSs (10,19). Instead, CaLeuRS prevented insertion of Nva into proteome mainly via post-transfer editing no matter whether Nva has been loaded onto either CatRNALeu or CatRNASer. Collectively, we further improved our understanding of mechanism and significance of genetic code ambiguity in C. albicans and revealed interesting properties of both aminoacylation and editing reactions by CaLeuRS. Furthermore, the capacity of eukaryotic LeuRSs at aminoacylating CatRNASer suggests the possibility of reconstructing proteome of other eukaryotes by simply introducing this unique tRNASer.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Natural Science Foundation of China [31270852, 31000355]; National Key Basic Research Foundation of China [2012CB911000]. Funding for open access charge: [31270852, 2012CB911000].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Prof. Jiang-Ye Chen in their institute for providing C. albicans genome and Dr Gilbert Eriani (CNRS, Strasbourg, France) for giving plasmid expressing E. coli CCase. The authors gratefully acknowledges the support of SA-SIBS scholarship program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ibba M, Söll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:617–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schimmel P. Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases: general scheme of structure-function relationships in the polypeptides and recognition of transfer RNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1987;56:125–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.001013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ibba M, Söll D. Quality control mechanisms during translation. Science. 1999;286:1893–1897. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jakubowski H. Quality control in tRNA charging — editing of homocysteine. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2011;58:149–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ling J, Reynolds N, Ibba M. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis and translational quality control. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;63:61–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giegé R, Sissler M, Florentz C. Universal rules and idiosyncratic features in tRNA identity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5017–5035. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.22.5017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fersht AR. Enzymic editing mechanisms and the genetic code. Proc. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 1981;212:351–379. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1981.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loftfield RB, Vanderjagt D. The frequency of errors in protein biosynthesis. Biochem. J. 1972;128:1353–1356. doi: 10.1042/bj1281353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu B, Yao P, Tan M, Eriani G, Wang ED. tRNA-independent pre-transfer editing by class I leucyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:3418–3424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806717200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan M, Zhu B, Zhou XL, He R, Chen X, Eriani G, Wang ED. tRNA-dependent pre-transfer editing by prokaryotic leucyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:3235–3244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.060616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou XL, Ruan ZR, Huang Q, Tan M, Wang ED. Translational fidelity maintenance preventing Ser mis-incorporation at Thr codon in protein from eukaryote. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:302–314. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JW, Beebe K, Nangle LA, Jang J, Longo-Guess CM, Cook SA, Davisson MT, Sundberg JP, Schimmel P, Ackerman SL. Editing-defective tRNA synthetase causes protein misfolding and neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;443:50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature05096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lincecum TL, Jr, Tukalo M, Yaremchuk A, Mursinna RS, Williams AM, Sproat BS, Van Den Eynde W, Link A, Van Calenbergh S, Grøtli M, et al. Structural and mechanistic basis of pre- and post-transfer editing by leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:951–963. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukunaga R, Yokoyama S. Crystal structure of leucyl-tRNA synthetase from the archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii reveals a novel editing domain orientation. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tukalo M, Yaremchuk A, Fukunaga R, Yokoyama S, Cusack S. The crystal structure of leucyl-tRNA synthetase complexed with tRNALeu in the post-transfer-editing conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:923–930. doi: 10.1038/nsmb986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukunaga R, Yokoyama S. Aminoacylation complex structures of leucyl-tRNA synthetase and tRNALeu reveal two modes of discriminator-base recognition. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:915–922. doi: 10.1038/nsmb985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palencia A, Crépin T, Vu MT, Lincecum TL, Jr, Martinis SA, Cusack S. Structural dynamics of the aminoacylation and proofreading functional cycle of bacterial leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:677–684. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao P, Zhou XL, He R, Xue MQ, Zheng YG, Wang YF, Wang ED. Unique residues crucial for optimal editing in yeast cytoplasmic leucyl-tRNA synthetase are revealed by using a novel knockout yeast strain. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:22591–22600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X, Ma JJ, Tan M, Yao P, Hu QH, Eriani G, Wang ED. Modular pathways for editing non-cognate amino acids by human cytoplasmic leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:235–247. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan M, Yan W, Liu RJ, Wang M, Chen X, Zhou XL, Wang ED. A naturally occurring nonapeptide functionally compensates for the CP1 domain of leucyl-tRNA synthetase to modulate aminoacylation activity. Biochem. J. 2012;443:477–484. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kisumi M, Sugiura M, Chibata I. Biosynthesis of norvaline, norleucine, and homoisoleucine in Serratia marcescens. J. Biochem. 1976;80:333–339. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soini J, Falschlehner C, Liedert C, Bernhardt J, Vuoristo J, Neubauer P. Norvaline is accumulated after a down-shift of oxygen in Escherichia coli W3110. Microb. Cell Fact. 2008;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nandi P, Sen GP. An antifungal substance from a strain of B subtilis. Nature. 1953;172:871–872. doi: 10.1038/172871b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Apostol I, Levine J, Lippincott J, Leach J, Hess E, Glascock CB, Weickert MJ, Blackmore R. Incorporation of norvaline at leucine positions in recombinant human hemoglobin expressed in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:28980–28988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen JF, Guo NN, Li T, Wang ED, Wang YL. CP1 domain in Escherichia coli leucyl-tRNA synthetase is crucial for its editing function. Biochemistry(US) 2000;39:6726–6731. doi: 10.1021/bi000108r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lue SW, Kelley SO. An aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase with a defunct editing site. Biochemistry. 2005;44:3010–3016. doi: 10.1021/bi047901v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou XL, Tan M, Wang M, Chen X, Wang ED. Post-transfer editing by a eukaryotic leucyl-tRNA synthetase resistant to the broad-spectrum drug AN2690. Biochem. J. 2010;430:325–333. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos MA, Perreau VM, Tuite MF. Transfer RNA structural change is a key element in the reassignment of the CUG codon in Candida albicans. EMBO J. 1996;15:5060–5068. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki T, Ueda T, Watanabe K. The ‘polysemous’ codon–a codon with multiple amino acid assignment caused by dual specificity of tRNA identity. EMBO J. 1997;16:1122–1134. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rocha R, Pereira PJ, Santos MA, Macedo-Ribeiro S. Unveiling the structural basis for translational ambiguity tolerance in a human fungal pathogen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:14091–14096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102835108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou XL, Wang M, Tan M, Huang Q, Eriani G, Wang ED. Functional characterization of leucine-specific domain 1 from eukaryal and archaeal leucyl-tRNA synthetases. Biochem. J. 2010;429:505–513. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou XL, Zhu B, Wang ED. The CP2 domain of leucyl-tRNA synthetase is crucial for amino acid activation and post-transfer editing. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:36608–36616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806745200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou XL, Du DH, Tan M, Lei HY, Ruan LL, Eriani G, Wang ED. Role of tRNA amino acid-accepting end in aminoacylation and its quality control. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:8857–8868. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christian T, Hou YM. Distinct determinants of tRNA recognition by the TrmD and Trm5 methyl transferases. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;373:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Wang E, Wang Y. Overproduction and purification of Escherichia coli tRNALeu. Sci. China, C, Life Sci. 1998;41:225–231. doi: 10.1007/BF02895095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gruic-Sovulj I, Uter N, Bullock T, Perona JJ. tRNA-dependent aminoacyl-adenylate hydrolysis by a nonediting class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:23978–23986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hati S, Ziervogel B, Sternjohn J, Wong FC, Nagan MC, Rosen AE, Siliciano PG, Chihade JW, Musier-Forsyth K. Pre-transfer editing by class II prolyl-tRNA synthetase: role of aminoacylation active site in “selective release” of noncognate amino acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:27862–27872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moura GR, Paredes JA, Santos MA. Development of the genetic code: insights from a fungal codon reassignment. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomes AC, Miranda I, Silva RM, Moura GR, Thomas B, Akoulitchev A, Santos MA. A genetic code alteration generates a proteome of high diversity in the human pathogen Candida albicans. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R206. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wakasugi K, Quinn CL, Tao N, Schimmel P. Genetic code in evolution: switching species-specific aminoacylation with a peptide transplant. EMBO J. 1998;17:297–305. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shiba K, Schimmel P, Motegi H, Noda T. Human glycyl-tRNA synthetase. Wide divergence of primary structure from bacterial counterpart and species-specific aminoacylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:30049–30055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shiba K, Suzuki N, Shigesada K, Namba Y, Schimmel P, Noda T. Human cytoplasmic isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase: selective divergence of the anticodon-binding domain and acquisition of a new structural unit. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:7435–7439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu C, Gamper H, Liu H, Cooperman BS, Hou YM. Potential for interdependent development of tRNA determinants for aminoacylation and ribosome decoding. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:329. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roy H, Ling J, Irnov M, Ibba M. Post-transfer editing in vitro and in vivo by the beta subunit of phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase. EMBO J. 2004;23:4639–4648. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong FC, Beuning PJ, Nagan M, Shiba K, Musier-Forsyth K. Functional role of the prokaryotic proline-tRNA synthetase insertion domain in amino acid editing. Biochemistry(US) 2002;41:7108–7115. doi: 10.1021/bi012178j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dock-Bregeon A, Sankaranarayanan R, Romby P, Caillet J, Springer M, Rees B, Francklyn CS, Ehresmann C, Moras D. Transfer RNA-mediated editing in threonyl-tRNA synthetase. The class II solution to the double discrimination problem. Cell. 2000;103:877–884. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silva RM, Paredes JA, Moura GR, Manadas B, Lima-Costa T, Rocha R, Miranda I, Gomes AC, Koerkamp MJ, Perrot M, et al. Critical roles for a genetic code alteration in the evolution of the genus Candida. EMBO J. 1997;26:4555–4565. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soma A, Uchiyama K, Sakamoto T, Maeda M, Himeno H. Unique recognition style of tRNA(Leu) by Haloferax volcanii leucyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;293:1029–1038. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soma A, Kumagai R, Nishikawa K, Himeno H. The anticodon loop is a major identity determinant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae tRNA(Leu) J. Mol. Biol. 1996;263:707–714. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.