Abstract

Through a combination of genome mining, gene knockouts, and comparative metabolomic studies, a new biosynthetic pathway to validoxylamine A has been discovered in Actinosynnema mirum DSM 43827. The study revealed the rich diversity of biosynthetic pathways to pseudosugar-containing natural products.

Keywords: metabolomics, validoxylamine A, pseudosugar, Actinosynnema mirum, pseudoglycosyltransferase

In recent years, a vast number of microbial genomes have been sequenced, and publicly accessible genetic databases have grown exponentially. The wide availability of these genetic data has led to the identification of thousands of unknown gene clusters. Many of these cryptic gene clusters are predicted to code for biosynthetic pathways to novel bioactive natural products; therefore, they hold great promise for the future of drug discovery. Consequently, genome mining-based discovery is becoming a valuable tool for exploring and identifying bioactive compounds.

As part of our studies on the biosynthesis of pseudosugar-containing natural products, we recently discovered a new class of enzymes, called the pseudoglycosyltransferases (PsGTs).[1] These enzymes are highly similar to glycosyltransferases, but in contrast to the ordinary glycosyltransferases, they do not catalyze glycosylation reactions. Instead, they catalyze nonglycosidic C-N couplings in the biosynthesis of pseudosugar-containing natural products, such as the antidiabetic drug acarbose and the antifungal antibiotic validamycin A (Scheme S1).

Using protein sequences of known PsGTs as queries, we carried out genome mining studies to exploit the wealth of the genetic information available in the NCBI genome database. We discovered a number of cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters in both Gram-(+) and Gram-(−) bacteria that contain PsGT homologues. All of these bacteria, however, have never been reported to produce pseudosugar-containing natural products. Among them is Actinosynnema mirum DSM 43827, a soil bacterium that has only been known to produce β-lactam antibiotic nocardicins [2] and the unique siderophore antibiotic mirubactin.[3] However, whole genome analysis of A. mirum, using antiSMASH (antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell) program[4] resulted in the prediction of 25 cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters for secondary metabolites; interestingly, the PsGT cluster was not one of them.

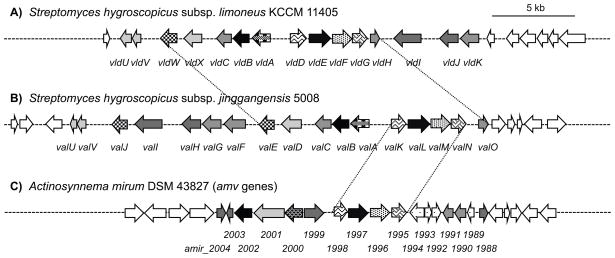

The putative PsGT in A. mirum (Amir_1997) shows 61.8% identity to VldE, a pseudoglycosyltransferase from the validamycin pathway in Streptomyces hygroscopicus subsp. limoneus.[1] Besides amir_1997, there are a number of genes in the cluster, whose products may be involved in pseudo-(amino)-sugar biosynthesis. Those include an aminotransferase (Amir_1996), two oxidoreductases (Amir_1995 and Amir_1998), a nucleotidyltransferase (Amir_2002), and a hydrolase/phosphatase (Amir_1991) (Figure 1, Table S1).

Figure 1.

Genetic organization of pseudo-oligosaccharide biosynthetic gene clusters in various organisms. A) the validamycin cluster in S. hygroscopicus subsp. limoneus. B) the validamycin cluster in S. hygroscopicus subsp. jinggangensis 5008. C) the cryptic gene cluster in Actinosynnema mirum that contains PsGT (amir_1997) and EVS (amir_2000) genes.

Interestingly, the key 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone synthase (EEVS) gene, which is necessary for the formation of the pseudosugar unit, is missing from this cluster. Instead, a homologous gene (amir_2000), whose product shows 40.1% identity (70.7% similarity) to 3-dehydroquinate synthase (DHQS) (Halha_0528) from Halobacteroides halobius DSM 5150, is present. A combination of PsGT and DHQS (instead of EEVS), however, is rather unusual, as the DHQS product does not usually serve as a substrate for the former enzyme. Indeed, a detailed biochemical study of Amir_2000 revealed its lack of DHQS activity.[5] The enzyme catalyzes an unprecedented cyclization reaction of sedoheptulose 7-phosphate, a product of the pentose phosphate pathway, to give 2-epi-valiolone, indicating that it is a 2-epi-valiolone synthase (EVS), not a DHQS.[5] It is noteworthy that 2-epi-valiolone has never been previously reported to be involved in the biosynthesis of natural products.

Furthermore, we also found a gene (amir_2001) within the cluster that encodes a protein with two putative functional domains: a kinase (N-terminal region) and an epimerase (C-terminal region). These kinase and epimerase domains are only distantly similar to the cyclitol kinase ValC (17.7% identity) and cyclitol epimerase ValD (16.4% identity) of S. hygroscopicus 5008. To determine if A. mirum DSM 43827 can produce pseudosugar-derived natural products, we cultured the bacterium in seven different media (see Supporting Information). Each culture was fractionated to give cationic polar metabolites (DOWEX 50W-passed extracts) and n-BuOH extracts, and the products were analyzed by HPLC, MS, and 1H NMR. Despite our concerted efforts, no pseudosugar-containing compounds could be detected in those extracts.

We then decided to genetically inactivate the cryptic biosynthetic genes and compare their phenotypes with those of the wild-type strain. The genes amir_1997 and amir_2000 were inactivated by DNA homologous recombination techniques through conjugal transfer of disruption plasmids into the host cells employing a modified protocol for Streptomyces conjugation (see Experimental Section). To our knowledge, this is the first reported example of genetic manipulations in A. mirum. Whereas amir_2000 was inactivated by inserting plasmid DNA harboring an apramycin-resistant gene (acc(3)IV) through a single crossover event, amir_1997 was inactivated by an in-frame deletion through double-crossover events (Figure S1). We employed these two different techniques to demonstrate the applicability of both methods for gene inactivation in A. mirum. The genotypes of the mutants (ΔPsGT and EVS::aprR) were confirmed by PCR amplification (Figure S2).

To investigate the effects of the genetic knockouts on the production of secondary metabolites in A. mirum, samples obtained from the wild-type as well as the ΔPsGT and EVS::aprR mutants were subjected to comparative metabolic profiling. The wild-type and the mutants were cultured in seven different liquid media, as described earlier, and the metabolites were analyzed by HPLC, ESI-MS, and 1H NMR. However, due to the complexity of the samples, it was hard for us to determine the differences between the wild-type and the mutant metabolomes.

To investigate the effects of the gene inactivation further, we employed LC-HR-ESI-MS/MS for statistical comparative metabolomic studies. The comparative metabolomics approach has been applied in the areas of drug (xenobiotic) metabolism and toxicology.[6] Moreover, a combination of genetic mutations and comparative metabolomics has been used in deciphering gene function in biological systems.[7, 8] However, this statistical -omics approach has not been widely employed in genome mining-based natural products discovery.

For this comparative metabolomic study, we cultured each of the wild-type and mutant strains of A. mirum in a modified STA medium[9] in five independent flasks. Samples of cationic polar metabolites were prepared from the culture broths and subjected to LC-HR-ESI-MS/MS analyses. Raw LC-MS/MS data files were first imported into MarkerView™ software (AB SCIEX) for initial data processing, including feature detection, peak alignment, peak integration, principal component analysis (PCA), and discriminant analysis (DA). In this case, a feature was defined as any unidentified m/z value detected in the wild-type but not in the mutants.

Principal component analysis and discriminant analysis (PCA-DA) score plots clearly demarcated metabolic profile changes between the wild-type and the mutants (Figure 2A). A volcano plot for polar metabolites of wild-type versus mutants detected in positive ion mode was analyzed. The results indicated the presence of an ion with m/z 336.1 in the wild-type but not in the mutants. The m/z 336.1 ion appeared at a significantly low p-value (< 0.05) and a large fold change (Figure 2B). A plot of the m/z 336.1 ion of all samples also indicated the presence of this metabolite only in the wild-type (Figure S3), suggesting that both Amir_1997 and Amir_2000 are critical for its production. High-resolution TOF-MS analysis of the compound gave m/z 336.1657 [M+H]+ with a deduced molecular formula of C14H26NO8; whereas, LC-MS/MS analysis showed a fragment at m/z 178.1077 [M+H]+ with a deduced molecular formula of C7H16NO4 (Figure S4). These molecular formulas are the same as those of validoxylamine A and validamine moieties, respectively (Figure S5).[10, 11]

Figure 2.

Statistical comparative metabolomic analysis of A. mirum wild-type, ΔPsGT and EVS::aprR mutants. A) PCA-DA scores plot of A. mirum wild-type (n5), ΔPsGT mutant (n5), and EVS::aprR mutant (n5) (DA1DA2, 70% of variance). Analysis is on the basis of polar metabolites detected in positive ion mode. B) Volcano plot of polar metabolites from A. mirum wild-type, ΔPsGT mutant, and EVS::aprR mutant detected in positive ion mode. Log 10 (fold change) values are on the basis of average (n 5/group) responses calculated by MarkerView™ software.

Subsequently, comparisons of the A. mirum metabolite with authentic validoxylamine A by LC-MS/MS revealed that both compounds have the same LC retention time (4.6 min) and give identical MS fragmentation patterns (Figure S4). These results strongly suggest that the product of the cryptic gene cluster is validoxylamine A. However, since the precursor of the pseudo-sugar in A. mirum is different from that in S. hygroscopicus, along with the presence of several non-orthologous genes within the A. mirum cluster, the possibility that the product has a different stereochemistry was also considered.

To determine the chemical structure of the metabolite, the wild-type strain was cultured in modified STA medium[9] (1 L) for 5 days, and the product was purified using DOWEX 50W (H+ form), DOWEX 1 (OH− form), and HPLC (C18 column), to give a white solid (1.8 mg) (Scheme S2). Analysis of the compound by 1H NMR and HR-ESI-MS, and direct comparisons of the data with those of authentic validoxylamine A, unambiguously confirmed the identity of the compound as validoxylamine A (Figures S6–S8).

The identification of validoxylamine A as a product of the gene cluster is rather surprising because (a) the overall organization of the cluster, except for the four-gene cassette amir_1995 – amir_1998, is different from those in S. hygroscopicus; (b) the key enzyme for the formation of the pseudosugar unit in A. mirum (Amir_2000) is phylogenetically and functionally distinct from those found in S. hygroscopicus; and (c) the kinase and the epimerase in A. mirum exist as a fusion protein (Amir_2001), and they are significantly different from the cyclitol kinases and epimerases found in S. hygroscopicus. Phylogenetic analysis of Amir_2001 revealed that the kinase domain belongs to a branch located distantly from those of the known cyclitol kinases, ValC (valienone 7-kinase)[12] and AcbM (2-epi-5-epi-valienol 7-kinase)[13] (Figure S9). The epimerase domain, while different, is more closely related to the 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone 2-epimerases ValD and CetB (from the validamycin and cetoniacytone clusters)[14, 15] than to the 2-epi-5-epi-valiolone 7-phoshate 2-epimerase AcbO (from the acarbose cluster)[16] (Figure S10). These results suggest that the timing of and the substrates for the phosphorylation and epimerization reactions in A. mirum are different from those found in other organisms (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Biosynthetic pathways to acarbose and validamycin A, and a proposed alternative pathway to validoxylamine A in A. mirum. Reaction steps from valienone 7-phosphate to validoxylamine A in A. mirum are expected to be the same as those in S. hygroscopicus.

In summary, using a combination of gene knockouts and a comparative metabolomics approach, we identified a new biosynthetic pathway to validoxylamine A in A. mirum DSM 43827. This discovery not only underscores the rich diversity of biosynthetic enzymes involved in the formation of pseudosugar units in nature, but also provides a new tool for biosynthetic pathway predictions and genome mining-based discovery. The non recognition of the genes by the antiSMASH program as a natural product biosynthetic gene cluster is most likely due to the fact that Amir_2000 is more similar to DHQS than to EEVS. Thus, Amir_2000, as well as Amir_1997, should now be included as additional references to guide the prediction and identification of cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters for pseudosugar-derived natural products.

Experimental Section

Detailed experimental methods can be found in the Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Jan F. Stevens and Jeffrey Morré for technical assistance with the comparative metabolomic study and Denny Weber and Jaewoo Choi for help with editing the manuscript. The project described was supported by grant R01AI061528 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and by the Herman-Frasch Foundation. This publication was made possible, in part, by the Mass Spectrometry Facilities and Service Core of the Environmental Health Sciences Center, Oregon State University, grant number P30 ES00210, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chembiochem.org or from the author.

References

- 1.Asamizu S, Yang J, Almabruk KH, Mahmud T. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12124–12135. doi: 10.1021/ja203574u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanabe K, Okuda T, Yokose K, Furumai T, Maruyama HB. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1983;36:321–324. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giessen TW, Franke KB, Knappe TA, Kraas FI, Bosello M, Xie X, Linne U, Marahiel MA. J Nat Prod. 2012;75:905–914. doi: 10.1021/np300046k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medema MH, Blin K, Cimermancic P, de Jager V, Zakrzewski P, Fischbach MA, Weber T, Takano E, Breitling R. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W339–346. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asamizu S, Xie P, Brumsted CJ, Flatt PM, Mahmud T. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:12219–12229. doi: 10.1021/ja3041866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drexler DM, Reily MD, Shipkova PA. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;399:2645–2653. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tohge T, Fernie AR. J Vis Exp. 2012:e3487. doi: 10.3791/3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quanbeck SM, Brachova L, Campbell AA, Guan X, Perera A, He K, Rhee SY, Bais P, Dickerson JA, Dixon P, Wohlgemuth G, Fiehn O, Barkan L, Lange I, Lange BM, Lee I, Cortes D, Salazar C, Shuman J, Shulaev V, Huhman DV, Sumner LW, Roth MR, Welti R, Ilarslan H, Wurtele ES, Nikolau BJ. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3:15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asamizu S, Shiro Y, Igarashi Y, Nagano S, Onaka H. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2011;75:2184–2193. doi: 10.1271/bbb.110474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horii S, Iwasa T, Mizuta E, Kameda Y. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1971;24:59–63. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.24.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asano N, Takeuchi M, Ninomiya K, Kameda Y, Matsui K. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1984;37:859–867. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minagawa K, Zhang Y, Ito T, Bai L, Deng Z, Mahmud T. Chembiochem. 2007;8:632–641. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang CS, Stratmann A, Block O, Bruckner R, Podeschwa M, Altenbach HJ, Wehmeier UF, Piepersberg W. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22853–22862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202375200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bai L, Li L, Xu H, Minagawa K, Yu Y, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Floss HG, Mahmud T, Deng Z. Chem Biol. 2006;13:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu X, Flatt PM, Xu H, Mahmud T. Chembiochem. 2009;10:304–314. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang CS, Podeschwa M, Altenbach HJ, Piepersberg W, Wehmeier UF. FEBS Lett. 2003;540:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.