Abstract

This study examined organizational levers that impact work–family experiences, participant health, and subsequent turnover. Using a sample of 179 women returning to full-time work 4 months after childbirth, we examined the associations of 3 job resources (job security, skill discretion, and schedule control) with work-to-family enrichment and the associations of 2 job demands (psychological requirements and nonstandard work schedules) with work-to-family conflict. Further, we considered subsequent impact of work-to-family conflict and enrichment on women’s health (physical and mental health) 8 months after women returned to work and the impact of health on voluntary turnover 12 months after women returned to work. Having a nonstandard work schedule was directly and positively related to conflict, whereas schedule control buffered the effect of psychological requirements on conflict. Skill discretion and job security, both job resources, directly and positively related to enrichment. Work-to-family conflict was negatively related to both physical and mental health, but work-to-family enrichment positively predicted only physical health. Physical health and mental health both negatively influenced turnover. We discuss implications and opportunities for future research.

Keywords: work–family conflict, work–family enrichment, health, turnover, job demands

Working mothers make up a substantial proportion of today’s workforce. In the United States, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2010), 71% of women with children under the age of 18 were working or looking for work and nearly 60% of women with young children were employed. Yet, a large number of mothers return to work after childbirth and subsequently exit the labor force. Although some argue these mothers are “scaling back” to minimize role overload (Becker & Moen, 1999), it remains unclear why women choose to leave their jobs or what organizations can do to retain these valuable women. The birth of a child may act as a significant event or shock that, according to the unfolding theory of turnover, may lead working mothers to reevaluate their work setting or to leave voluntarily (Lee & Mitchell, 1994). Turnover of valued employees can be costly and disruptive to organizations (Holtom, Mitchell, Lee, & Eberly, 2008). However, very little is known about the levers that play a role in women’s turnover decisions after childbirth.

Juggling the competing demands of work and family can be challenging for mothers and can result in work–family conflict, especially when women have few resources with which to meet the demands of their daily work and family lives (Fine-Davis, Fagnani, Giovannini, Hojgaard, & Clarke, 2004). However, women can also benefit from participating in multiple roles through the process of enrichment, in which resources gained at work can improve quality of life at home and even buffer the negative effects of work demands (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006; Grzywacz & Bass, 2003). Our goal in this study was to understand how the interconnections between the event of childbirth and the attributes of the job shape work–family conflict, enrichment, and subsequent outcomes (e.g., health) that ultimately contribute to turnover decisions. We developed this model using tenets of the job demands–resources model (Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2003) and the unfolding model of turnover (Holtom, Mitchell, Lee, & Inderrieden, 2005). We tested this model using data obtained from working mothers 4, 8, and 12 months after childbirth.

This study makes a number of contributions. First, we tested our model over time with an understudied population, working mothers of infants. This sample is unique in that the transition back to work is a pivotal point for a new mother and offers an important opportunity to understand how job attributes can either contribute to or detract from the mother’s decision to stay with her employing organization after she returns to work. Second, responding to frequent calls for theories that capture positive and negative experiences in the work–family interface (Eby, Casper, Lockwood, Bordeaux, & Brinley, 2005; Geurts & Demerouti, 2003; MacDermid & Harvey, 2006), we applied a theoretical model that encompasses both resources and demands in the work environment to explore organizational levers that contribute to work-to-family conflict and work-to-family enrichment. Third, we situated our investigation of the work–family interface in a broader theoretical framework (unfolding model of turnover) that allowed us to examine the effect of the unique shock of childbearing on the turnover decision.

Theoretical Foundations

The unfolding model of turnover argues that decisions to exit a job or position occur after a shock and the subsequent unfolding of shock-related events over time (Holtom et al., 2005, 2008). A shock is a particular jarring event that initiates a psychological analysis involved in quitting. There are a number of kinds of shock. Our focus here is on childbirth, a personal, known, and positive form of shock (Holtom et al., 2005) that researchers identify as a “family issue.” In this path, the shock provides an image violation that initiates a comparison of the current job with various alternatives. Further, women, the focus of our study, more commonly follow this path (Donnelly & Quinn, 2006). Thus, we believe the shock of childbirth causes women to analyze their current job state to determine their course of action. We believe that, given the nature of the shock, the job demands–resources model provides a way of understanding their evaluation of the job and its impact on the work–family interface.

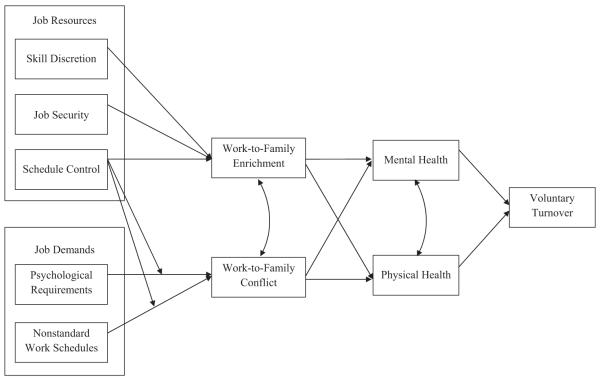

The job demands–resources model (JD-R) is built on the underlying assumption that every job has specific characteristics that can be categorized as demands and resources (Bakker et al., 2003). Job resources are the physical, psychological, or organizational aspects of the job that stimulate growth, learning, and development. Job demands are the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained effort or skills (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). A core proposition of the JD-R model is that there are two different yet parallel underlying psychological processes linking job resources and demands to outcomes. Job resources contribute to beneficial outcomes through motivation and other mechanisms that shift employees’ attention beyond themselves (Bakker & Geurts, 2004; Schaufeli, Bakker, & Van Rhenen, 2009).These mechanisms include work–family enrichment, which has been defined as “the extent to which experiences in one role improve the quality of life in the other role” (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006, p. 73), and employee health. On the other hand, job demands undermine beneficial outcomes through strain and mechanisms that focus employees’ attention on themselves, contributing to work–family conflict, “a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect” (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985, p. 77), and subsequent health deterioration. The evaluation of the unfolding of events between the work and family domains contributes to turnover decisions by the working mother of an infant. Drawing on a sample of women who had recently experienced a shock, we posited that job resources such as skill discretion, job security, and schedule control contribute to work-to-family enrichment, whereas job demands such as psychological requirements and nonstandard work schedules contribute to work-to-family conflict (see Figure 1). Finally, conflict and enrichment both contribute to physical and mental health and, ultimately, voluntary turnover.

Figure 1.

Theoretical job demands–resources model.

Job Attributes and the Work–Family Interface

Job demands

Demands are characteristics of the environment that require the individual to use resources. Recent research has found that the job demands of the mother relate positively to negative interactions with her child (Bass, Butler, Grzywacz, & Linney, 2009), suggesting that job demands create work-to-family conflict and other negative outcomes. Furthermore, job demands such as mandatory overtime have been found to lead to increases in turnover among new mothers by 6 months postpartum (Glass & Riley, 1998). We chose to look at two such workplace demands that we thought would be relevant to working mothers: psychological requirements of the job and nonstandard work schedules.

Psychological requirements at work are the cumulative appraisal of task requirements and workload (Karasek & Theorell, 1990). Psychological demands, such as role conflict at work (Boyar, Maertz, Mosley, & Carr, 2008), work pressure (Goodman & Crouter, 2009), and work overload (Aryee, Luk, Leung, & Lo, 1999), have positively related to work-to-family conflict. Psychological requirements from the work domain result in a depletion of resources for the job incumbent. As a result, the job incumbent is more strained and that spills over to the family. Thus, we believed that psychological requirements would contribute to work-to-family conflict in working mothers of infants.

Staines and Pleck (1984) demonstrated that working nonstandard hours or days (e.g., working a night or weekend shift) increases employee work-to-family conflict. Epidemiological research suggests that nonday shift work contributes to physiological and psychological strain due to disruptions of circadian rhythms and sleeping and eating patterns (e.g., Akerstedt, 1990; Bohle & Tilley, 1989). Working night shifts may cause fatigue; interfere with infant nursing; increase strain and irritability when interacting with a spouse or children during daylight hours (Davis, Goodman, Pirretti, & Almeida, 2008); increase difficulties with coordinating family schedules; and prevent mothers from attending a child’s school and social activities, assisting with a child’s activities, or participating in family meals or outings (Staines & Pleck, 1984). Kinnunen and Mauno (1998) found that working nonstandard shifts had deleterious consequences for family life. Nonweekday shifts (Fenwick & Tausig, 2001) and nonday shifts (Davis et al., 2008) negatively impact work-to-family conflict. Thus, we believed that nonstandard work schedules would contribute to work-to-family conflict in working mothers.

Hypothesis 1: Job demands (psychological requirements and nonstandard work schedules) contribute to greater work-to-family conflict.

Job resources

Resources are characteristics of the environment that help one achieve goals, address demands, or develop as an individual (Hobfoll, 1989). Resources such as schedule flexibility and supervisor or coworker support lower turnover among new mothers at 6 months postpartum (Glass & Riley, 1998). Certain job resources may enable new mothers to achieve work-to-family enrichment and improved health and, later, make them more likely to remain with their employing organization long after childbirth. However, other potential resources to new mothers are seriously understudied. We theorized that skill discretion, job security, and schedule control are likely to be salient resources for working mothers of infants, because each is critical in helping working mothers balance work demands with the needs of an infant while at the same time achieving work and family goals (Wayne, Grzywacz, Carlson & Kacmar, 2007).

Skill discretion is the extent to which a job requires the use of a variety of skills (Karasek, 1998). Skill discretion provides employees with a heightened sense of responsibility and meaning in their work as well as with intrinsic motivation (Hackman & Oldham, 1976), all of which are critical to a mother considering whether to keep her job during a time of major family transition. Skill discretion may also provide mothers the flexibility to meet their various responsibilities, which leads to cognitive and psychological benefits (Kohn & Schooler, 1978). Furthermore, these resources may foster positive load effects with respect to motivation, energy, new skills, or attitudes used to enable improved functioning at home when caring for children or interacting with a spouse (Friedman & Greenhaus, 2000; Geurts & Demerouti, 2003). Consistent with this idea, previous research has found associations between measures of skill variety and work-to-family enrichment (Grzywacz & Butler, 2005; Grzywacz & Marks, 2000). These associations suggest that skill discretion creates greater enrichment.

Job security is another resource that should heighten motivation and energy, particularly for mothers who are sensitive to the security of their jobs after returning from maternity leave. When working mothers believe that their tenure with an organization is not at risk (i.e., secure), they will have more energy and other resources with which to fully engage and perform both at work and at home. By contrast, the absence of job security leaves mothers preoccupied by thoughts of potential job loss, job searching, and financial hardship (Reisel, Chia, & Maloles, 2005). This is particularly difficult at the critical life transition of childbirth. Job security is positively related to “internal motivation,” whereas a lack of job security is related to physical, interpersonal, and psychological strain (Mak & Mueller, 2000; Oldham, Hackman, & Pearce, 1976). Similarly, perceived threat of job loss is highly related to worry (Brockner, Grover, Reed, & Dewitt, 1992). When job security is high, individuals are not distracted by worry or exhausted by strain; instead, they are able to engage more fully in responsibilities both inside and outside the workplace, thereby creating greater opportunity for work-to-family enrichment.

Schedule control, formally defined as the degree of control employees have over their daily working hours, is another important resource, particularly for working mothers of infants. Kelly and Moen (2007) suggested that schedule control is an essential component of workplace flexibility and the modern workplace. Workers who are more in control of their work schedules are better able to respond to unexpected demands, such as a sick baby or a work project with a short deadline. In essence, schedule control increases an employee’s ability to meet both work and family responsibilities (Voydanoff, 2005). Consistent with this notion, Thomas and Ganster (1995) demonstrated that flexible schedules benefit employee health by reducing work–family conflict. Other research suggests that schedule control specifically and job control more broadly are associated with greater work-to-family enrichment (Butler, Grzywacz, Bass, & Linney, 2005; Carlson, Grzywacz & Kacmar, 2010). Thus, evidence suggests that for working mothers, schedule control is a salient resource that likely enables greater work-to-family enrichment.

Hypothesis 2: Job resources (skill discretion, job security, and schedule control) contribute to greater work-to-family enrichment.

Buffering effects

The JD-R model further suggests that some resources buffer the deleterious effects of job demands (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Kahn & Byosserie, 1992). We posited that schedule control is such a resource: When individuals are confronted by one or more job demands, schedule control provides them with alternatives for meeting those demands while being attentive to other responsibilities. In other words, as women are able to control their work environment and adapt, less stress from the work domain may spill over to the family. Of the resources examined in this study, schedule control is unique in that it is both a resource and a buffer. It can be used when demands arise and is also directly amenable to use by the organization.

Extant research supports the notion that schedule control at work can reduce the negative consequences of job demands on work–family and health outcomes (e.g., Ala-Mursula, Vahtera, Linna, Pentti, & Kivimäki, 2005; Geurts, Beckers, Taris, Kompier, & Smulders, 2009; Härmä, 2006; Tucker & Rutherford, 2005; Van Der Hulst & Geurts, 2001). For example, Geurts et al. found that flextime (i.e., control over when work begins and ends each day) buffered the effects of working hours on work-to-family conflict. Fenwick and Tausig (2001) found that schedule control buffered the effects of nonstandard shifts on general health outcomes among dual career families. Furthermore, nonflexible work schedules increase experiences of work-to-family conflict among mothers with young children, which in turn contributes to increased depressive symptoms (Goodman & Crouter, 2009). Therefore, we hypothesized that in a cohort of working mothers with infants, schedule control would play a moderating role in relationship between job demands and work-to-family conflict.

Hypothesis 3: Schedule control buffers the effect of job demands (psychological requirements and nonstandard work schedules) on work-to-family conflict.

Work-to-Family Conflict and Enrichment With Health Outcomes

Physical and mental health are core capacities of the ability of workers to maintain their job and perform well. Both work-to-family conflict and, to a lesser extent, work-to-family enrichment have related to health outcomes in past research. Killien, Habermann, and Jarrett (2001) have commented at length on postpartum depression, and they provided evidence that difficulties in combining work and family are associated with elevated depressive symptoms in the postpartum period. Several other longitudinal studies have demonstrated that work-to-family conflict predicts poorer mental and physical health over time (Goodman & Crouter, 2009; Grandey & Cropanzano, 1999; Grant-Vallone & Donaldson, 2001; Kinnunen, Geurts, & Mauno, 2004; Van Der Heijden, Demerouti, Bakker, and the NEXT Study Group, 2008; Van Steen-bergen & Ellemers, 2009). Likewise, the energy, motivation, and positive affect gained from workplace resources may allow a mother to better fulfill her family role and contribute positively to her mental and physical health, as previous research has related work–family enrichment with specific indicators of physical health (Van Steenbergen & Ellemers, 2009) and psychological health (Gareis, Barnett, Ertel, & Berkman, 2009). One study also found that postpartum resource gain helps offset resource loss during pregnancy to reduce postpartum depressive mood (Wells, Hobfoll, & Lavin, 1999). However, most of these studies used narrow assessments of health that focused on one or two indicators of physical or mental symptoms (e.g., depressive symptoms, somatic complaints). Although these are important dimensions of health, such assessments are poorly equipped to capture the complexity of human health (Grzywacz & Ganong, 2009). Research using more holistic assessments of health would provide a meaningful alternative perspective to more specific health assessments.

Hypothesis 4: Work-to-family conflict contributes to poorer physical and mental health, whereas work-to-family enrichment contributes to better physical and mental health.

Health Outcomes and Voluntary Turnover

A working mother’s evaluation of her work situation is likely to be influenced by the culmination of these job attributes on the work–family interface and its subsequent impact on health outcomes. Health is a basic resource that allows people to stay in place. According to the unfolding model of turnover, a woman who recently experienced the shock of childbirth may over time reevaluate the fit between her values and goals and those supported by her workplace. Should an image violation occur (i.e., her values and goals for her personal health and work–family equilibrium do not fit with her current work situation), she is likely to feel her needs are unmet and decide to search for a new job or stay home with her children (Holtom et al., 2005). Prior research has found that physical health problems (Jamal & Baba, 2003; Wegge, van Dick, Fisher, Wecking, & Moltzen, 2006) and emotional exhaustion (Wegge et al., 2006) positively relate to turnover motivations. Thus, if physical or mental health problems arise, a new mother is likely to question the value or even feasibility of staying in her current job.

Hypothesis 5: Poorer physical and mental health contribute to voluntary turnover.

Method

Sample and Procedure

The sample consists of full-time working mothers in Forsyth County, North Carolina. All births in this county in a given time period were monitored. Mothers were approached to be a part of the study. Five hundred eighteen mothers entered the sample frame. Of those randomly selected, 288 mothers were eligible for enrollment (18 years of age, working at least 30 hr per week, and planning on returning to work 30 or more hr by 4 months postpartum). Finally, 179 agreed to participate and completed an interview survey at three points in time: the Time 1 interview (4 months postpartum), the Time 2 interview (8 months post-partum), and a Time 3 interview (12 months postpartum). The average respondent age was 31 years. Of those sampled, 72% were White, 27% were Black, 1% were Asian, and the majority (79%) were married. The modal duration of maternity leave was 6 weeks, but less than half the mothers (48.1%) reported having paid maternity leave. They worked an average of 39.7 hr per week and had an average of 1.90 children living at home. Forty percent of the new mothers reported that the recent birth was their first child.

Measures

For each of the scales, responses were on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), unless otherwise indicated.

Skill discretion

We measured skill discretion with the seven-item scale from Karasek’s (1985) Job Content Questionnaire.

Job security

We measured job security with a three-item measure from Karasek’s (1985) Job Content Questionnaire.

Schedule control

We used a seven-item measure (Ala-Mursula et al., 2005) to assess how much control respondents perceived over their working times.

Psychological requirements

We measured psychological requirements with the nine-item scale from Karasek’s (1985) Job Content Questionnaire.

Nonstandard work schedules

We measured nonstandard work schedules with the following question: “When does your job require you to work?” We dichotomized this variable such that those working a typical 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. day were classified as standard and coded as 0; those with a nonstandard work schedule (e.g., night shift) were coded as 1.

Work-to-family conflict

Work-to-family conflict was measured with a five-item scale developed by Netemeyer, Boles, & McMurrian (1996).

Work-to-family enrichment

Work-to-family enrichment was measured with a four-item scale (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000).

Physical and mental health

At Time 2, health-related quality of life was assessed with the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales (SF-12; Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1996). The SF-12 is an internationally validated tool (Gandek et al., 1998) that has been used in over 1,700 published studies, including a previous study examining relationships of mental and physical health with turnover (Andrews & Wan, 2009). Responses to the 12 items tapping eight domains of health are combined to calculate two summary variables: physical health-related quality of life and mental health-related quality of life. The published, proprietary scoring algorithm was used to arrive at the summary scores (α = .80) and then standardized against a national population to yield average scores of 50 to allow comparison across studies (Ware, Snow, Kosinski, & Gandek, 1993).1 The scoring algorithm for both the SF-12 and its parent instrument (the Short-Form General Health Survey) has been used in over 16,000 published studies, including over 900 papers focused on work-related aspects of health and over 1,600 papers focused on women’s health (QualityMetric, 2010). Higher values on both variables indicate better health-related quality of life.

Voluntary turnover

In Time 3, we measured turnover by asking the mother if she had changed jobs since the last interview (0 = no job change, 1 = job change).

Controls

In our analyses, we controlled for the respondent’s poverty level, race, and number of children. The poverty variable was dichotomized to indicate whether respondent income was below or above the federal poverty line (10% were below in our sample). We treated race as dichotomous, such that the African American designation was coded as 1 and all others were coded as 0. Race and poverty level relate both to physical and mental health (House & Williams, 2000) and to turnover (Ng & Feldman, 2009; Shaw & Gupta, 2001). Because we theorized that new mothers are a unique population and that job demands and resources may be particularly salient with respect to a new mother’s first child, we included a control item for whether the infant was the mother’s first child.

Results

Analyses

Table 1 provides the means, standard deviations, correlations, and Cronbach’s alphas of the study variables. The SF-12 scoring algorithm is designed to produce orthogonal and completely unrelated summary scores for physical and mental health (Ware et al., 1996). However, when weights constructed from a general population are imposed on a comparatively healthier research sample, a negative association between physical and mental health can emerge (Taft, Karlsson, & Sullivan, 2001). The observed negative correlation between physical and mental health (see Table 1) therefore reflects an artifact of weighting and the self-selection of healthier women into the labor force (Repetti, Matthews, & Waldron, 1989).

Table 1.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Poverty | 0.08 | 0.27 | — | ||||||||||||

| 2. Race | 0.27 | 0.44 | .34** | — | |||||||||||

| 3. First child | 0.40 | 0.49 | .10 | −.04 | — | ||||||||||

| 4. Psychological requirements | 2.80 | 0.28 | −.01 | −.17* | .24** | (.74) | |||||||||

| 5. Nonstandard work schedules |

0.24 | 0.43 | .08 | .19* | .02 | .06 | — | ||||||||

| 6. Schedule control | 2.73 | 0.73 | −.07 | −.07 | .04 | −.11 | .03 | (.80) | |||||||

| 7. Skill discretion | 3.04 | 0.30 | −.04 | .01 | .05 | .22** | .00 | .05 | (.76) | ||||||

| 8. Job security | 3.28 | 0.57 | .00 | −.02 | .09 | .23** | .00 | .13 | .31** | (.74) | |||||

| 9. Work-to-family conflict | 2.43 | 0.93 | −.07 | .02 | −.10 | .12 | .23** | −.14 | .04 | −.10 | (.88) | ||||

| 10. Work-to-family enrichment | 2.66 | 0.83 | −.09 | −.03 | −.11 | .07 | .04 | .07 | .22** | .25** | .19* | (.71) | |||

| 11. Mental health | 50.78 | 6.86 | −.06 | −.15 | .05 | −.11 | −.03 | .05 | −.01 | .10 | −.25** | .02 | (.80) | ||

| 12. Physical health | 53.86 | 6.81 | −.22** | .13 | −.03 | −.02 | −.06 | .27** | .10 | .24** | −.18* | .10 | −.24** | (.80) | |

| 13. Turnover | 0.24 | 0.43 | .23** | .25** | .08 | −.09 | .12 | −.02 | .03 | −.17* | .12 | −.04 | −.14 | −.20** | — |

Note. Variables 1–10 were measured at Time 1 (4 months postpartum). Variables 11 and 12 were measured at Time 2 (8 months postpartum). Variable 13 was measured at Time 3 (12 months postpartum). Cronbach’s alpha is provided along the major diagonal. SD = standard deviation.

p < .05.

p < .01.

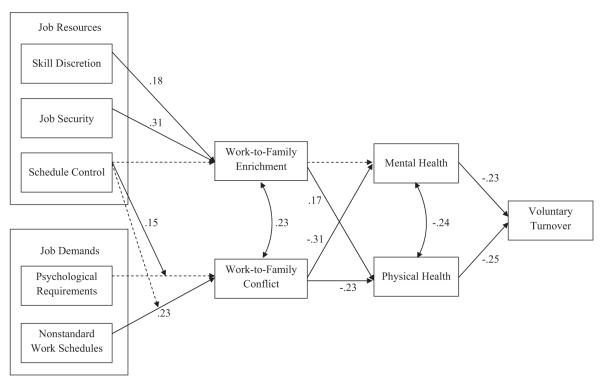

We used structural equation modeling in LISREL 8.8 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993) to test the hypothesized model (see Figure 1). All analyses used maximum likelihood estimation and observed scale variables, because the health variables were standardized on national averages and health item-level data were not available. Our hypothesized model fit the data well, χ2(35) = 46.49, p < .05, root-mean-square error of approximation = .042, comparative fit index = .93. In order to establish this was the best fitting model, we considered two competing models. The first model added five paths from the job demands and resources to turnover and did not provide significantly improved fit, Δχ2(5) = 8.79, p < .20. The second model added two paths from conflict and enrichment to turnover and did not provide significantly improved fit, Δχ2(2) = .05, p < .95. Therefore, our hypothesized model was the best fitting model. Most of the specified paths are significant, and the associations are in the expected direction (see Figure 2 for standardized path coefficients). The only significant control variables found were that race was related to physical health (−.25) and poverty was related to turnover (.17).

Figure 2.

Standardized path coefficients for model. Numbers are standardized path coefficients.

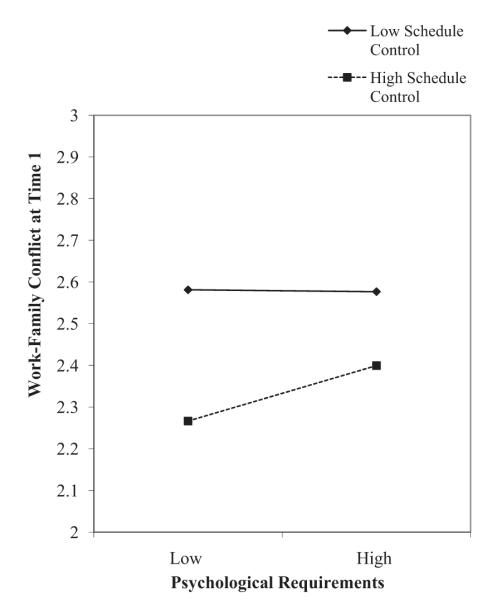

In partial support of Hypothesis 1, the main effect of job resources on work-to-family enrichment held such that greater skill discretion and job security were associated with greater work-to-family enrichment. However, there was a null association between schedule control and enrichment. In terms of job demands, women with a nonstandard work schedule reported greater work-to-family conflict, partially supporting Hypothesis 2, but no main effect between psychological requirements and conflict was supported. However, the association of psychological requirements with work-to-family conflict was moderated by level of schedule control, partially supporting Hypothesis 3. The moderating effect was interpreted by plotting two slopes with schedule control one standard deviation above and below the mean (see Figure 3; Stone & Hollenbeck, 1989). Contrary to expectation, the relationship between psychological requirements and work-to-family conflict was flat among those with low schedule control; by contrast, greater psychological demand was associated with greater work-to-family conflict among those with high schedule control. We conducted simple slopes tests for the lines graphed in Figure 3 to determine if the slopes differed from zero. Only the high schedule control line was significantly different from zero, t(6) = 3.02, p < .05. Finally, as expected, greater work-to-family conflict predicted poorer physical and mental health over time and greater work-to-family enrichment predicted better physical health, partially supporting Hypothesis 4. However, there was no evidence that work-to-family enrichment was associated with women’s mental health. Hypothesis 5 was fully supported, as both mental and physical health were negatively related to voluntary turnover.

Figure 3.

Moderation of schedule control on the relationship between psychological requirements and work-to-family conflict.

Discussion

The birth of a baby, although expected, can provide a shock to a working mother and her work–family situation. Our goal in this study was to develop a better understanding of this unique segment of the working population and address which organizational leverage points are particularly useful in influencing the health and turnover of new mothers. We achieved this goal using data obtained from working mothers of infants across three time periods to understand how job attributes and the work–family interface over time contribute to health and voluntary turnover. Results generally suggest that demands and resources of the work environment affect the experience of work-to-family conflict and work-to-family enrichment and, subsequently, health and turnover among working mothers of infants.

A contribution of this study is the explicit focus on working mothers of infants. Although this single community sample may have limited generalizability, research on working mothers of infants is generally missing from the broader work–family literature (cf. Killien et al., 2001). Given that 51.7% of mothers of infants are employed, most of them full time (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010), it is important that researchers focus more attention on this segment of the workforce. New mothers may be uniquely susceptible to leaving their employing organization, particularly in the year following childbirth (Stordeur & D’Hoore, 2007). Working mothers of infants likely provide a good representation for testing models of the work–family interface because the transition in family structure and interaction provides a natural experiment within which to examine putative antecedents and consequences of work–family experiences. Moreover, childbirth and returning to the workplace after the birth of a child exemplify a shock described by the unfolding model of turnover (Holtom et al., 2005). Although the birth of a child is often a positive experience, it is also jarring and is likely to initiate the psychological analyses involved in the turnover process. Such analyses are likely to make job demands and resources and subsequent work–family conflict and enrichment more salient as the new mother evaluates whether remaining with her employing organization is helpful or detrimental. Shocks may be work related or personal (Morrell, 2005), and this research suggests the interconnections between work and family are important drivers in a new mother’s turnover process.

Our findings suggest there are important levers organizations can employ to retain mothers who experience a shock of childbirth that initiates an analysis of their current job state including job demands and resources. Although job demands may lead to poor outcomes, resources such as skill discretion and job security lead to beneficial outcomes both for the organization and for the mother. Consistent with previous research, women whose jobs provide greater skill discretion and job security experience greater work–family enrichment (Bakker, Demerouti, & Euwema, 2005; Grzywacz & Butler, 2005; Voydanoff, 2004). Further, we found, as have other researchers (Davis et al., 2008; Fenwick & Tausig, 2001; Staines & Pleck, 1984), that a nonstandard work schedule contributes to greater work–family conflict among working mothers of infants. As predicted, work-to-family conflict was higher among individuals with low schedule control than individuals with high schedule control; however, there was a possible ceiling effect, given that conflict was high regardless of low or high psychological requirements. But among individuals with high schedule control, more schedule control exaggerates the effects of psychological demands on work-to-family conflict among working mothers of infants. These results are consistent with previous research (Grzywacz, Carlson, & Shulkin, 2008) showing that participation in multiple workplace flexibility programs was associated with greater stress and burnout for women but less stress and burnout for men. Women may be using schedule control to “fit more in” their daily lives as opposed to better manage their existing demands. This is an important area for future research. However, reducing demands is still critical, as our participants experienced the least work-to-family conflict when control was high and psychological requirements were low.

Our results provide further evidence of the work–family interface’s implications for individual health and turnover. As did previous studies that found associations between work–family conflict or work–family enrichment with physical illness indicators (i.e., Grant-Vallone & Donaldson, 2001; Van Steenbergen & Ellemers, 2009) or poor psychological well-being (i.e., Grzywacz, 2000; Kinnunen et al., 2004), we found that both work-to-family conflict and enrichment predicted physical health. We also found that work-to-family conflict but not enrichment predicted mental health. The lack of association was unexpected and suggests that work–family enrichment may be related to distinct domains of mental illness, such as depressive symptoms (Grzywacz & Bass, 2003), but not to mental health as a broader, more multidimensional state. Further, building on previous research, both forms of health were found to contribute to voluntary turnover (Wegge et al., 2006).

As with all research, this study has limitations. All data consisted of self-reports, which raises the possible threat of common methods bias. However, we measured the independent and dependent variables at different time periods to mitigate this issue (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). Also, reverse directionality between job attributes and work–family experiences cannot be ruled out. The limited-measurement time frame of voluntary turnover also restricted our opportunity to observe turnover and thus reduced variability in our turnover outcome. Another limitation is the possibility that the forced orthogonality of the physical and mental health-related quality of life summary measures of the SF-12 may have influenced the results observed in this study. Future research using multidimensional measures of health that do not impose orthogonality is needed. Finally, this research examined a focused population that could be expanded in future research to include working fathers.

In conclusion, our results suggest that organizations may be able to promote beneficial outcomes through systematic attempts to increase skill discretion and variety (e.g., cross-training employees for multiple functions). Employees working nonstandard work schedules need specific supports to minimize negative outcomes. Measures to improve mental and physical health, such as deliberate employee assistance programs or more integrative work–life initiatives, are important for retaining working mothers and deserve attention. Although further research is needed, the results of this study indicate the impact of job characteristics on work– family mechanisms that play a role in the mental and physical health and retention of working mothers as they make the pivotal transition back to work after childbirth.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development Grant R21 HD48601.

Footnotes

All analyses were replicated with unstandardized (raw) physical and mental health scores. Results were similar to those for the standardized scores.

Contributor Information

Dawn S. Carlson, Department of Management, Baylor University

Joseph G. Grzywacz, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Merideth Ferguson, Department of Management, Baylor University.

Emily M. Hunter, Department of Management, Baylor University

C. Randall Clinch, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Thomas A. Arcury, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine

References

- Akerstedt T. Psychological and physiological effects of shift work. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 1990;16:67–73. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ala-Mursula L, Vahtera J, Linna A, Pentti J, Kivimäki M. Employee worktime control moderates the effects of job strain and effort–reward imbalance on sickness absence: The 10-town study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005;59:851–857. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.030924. doi:10.1136/jech.2004.030924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews DR, Wan TTH. The importance of mental health to the experience of job strain: An evidence-guided approach to improve retention. Journal of Nursing Management. 2009;17:340–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00852.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2934.2008.00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryee S, Luk V, Leung A, Lo S. Role stressors, interrole conflict, and well-being: The moderating influence of spousal support and coping behaviors among employed parents in Hong Kong. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1999;54:259–278. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1998.1667. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The job demands–resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2007;22:309–328. doi:10.1108/02683940710733115. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Euwema MC. Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2005;10:170–180. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.170. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB. Dual processes at work in a call centre: An application of the job demands–resources model. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. 2003;12:393–417. doi:10.1080/13594320344000165. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker AB, Geurts SAE. Toward a dual-process model of work–home interference. Work and Occupations. 2004;31:345–366. doi:10.1177/0730888404266349. [Google Scholar]

- Bass BL, Butler AB, Grzywacz JG, Linney KD. Do job demands undermine parenting? A daily analysis of spillover and crossover effects. Family Relations. 2009;58:201–215. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00547.x. [Google Scholar]

- Becker PE, Moen P. “Scaling back”: Dual-earner couples’ work–family strategies. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61:995–1007. doi:10.2307/354019. [Google Scholar]

- Bohle P, Tilley AJ. The impact of night work on psychological well-being. Ergonomics. 1989;32:1089–1099. doi: 10.1080/00140138908966876. doi:10.1080/00140138908966876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyar SL, Maertz CP, Jr., Mosley DC, Jr., Carr JC. The impact of work/family demand on work–family conflict. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2008;23:215–235. doi:10.1108/02683940810861356. [Google Scholar]

- Brockner J, Grover S, Reed TF, Dewitt RL. Layoffs, job insecurity, and survivors’ work effort: Evidence of an inverted-U relationship. Academy of Management Journal. 1992;35:413–425. doi:10.2307/256380. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment characteristics of families in 2009 (USDL-10–0721) 2010 Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-databook-2010.pdf.

- Butler AB, Grzywacz JG, Bass BL, Linney KD. Extending the demands–control model: A daily diary study of job characteristics, work–family conflict and work–family facilitation. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2005;78:155–169. doi:10.1348/096317905X40097. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson DS, Grzywacz JG, Kacmar KM. The relationship of schedule flexibility and outcomes via the work–family interface. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2010;25:330–355. doi:10.1108/02683941011035278. [Google Scholar]

- Davis KD, Goodman WB, Pirretti AE, Almeida DM. Nonstandard work schedules, perceived family well-being, and daily stressors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:991–1003. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00541.x. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly DP, Quinn JJ. An extension of Lee and Mitchell’s unfolding model of voluntary turnover. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2006;27:59–77. doi:10.1002/job.367. [Google Scholar]

- Eby LT, Casper WJ, Lockwood A, Bordeaux C, Brinley A. Work and family research in IO/OB: Content analysis and review of the literature (1980–2002) Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2005;66:124–197. [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick R, Tausig M. Scheduling stress: Family and health outcomes of shift work and schedule control. American Behavioral Scientist. 2001;44:1179–1198. doi:10.1177/00027640121956719. [Google Scholar]

- Fine-Davis M, Fagnani J, Giovannini D, Hojgaard L, Clarke H. Fathers and mothers: Dilemmas of the work–life balance, a comparative study in four European countries. Kluwer Academic; Dordrecht, the Netherlands: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SD, Greenhaus JH. What happens when business professional confront life choices. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2000. Work and family—allies or enemies? [Google Scholar]

- Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, Sullivan M. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: Results from the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00109-7. doi:10.1016/S08954356(98)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gareis KC, Barnett RC, Ertel KA, Berkman LF. Work–family enrichment and conflict: Additive effects, buffering, or balance? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:696–707. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00627.x. [Google Scholar]

- Geurts SAE, Beckers DGJ, Taris TW, Kompier MAJ, Smulders PGW. Worktime demands and work–family interference: Does worktime control buffer the adverse effects of high demands? Journal of Business Ethics. 2009;84:229–241. doi:10.1007/s10551-008-9699-y. [Google Scholar]

- Geurts SAE, Demerouti E. Work/non-work interface: A review of theories and findings. In: Schabracq M, Winnubst J, Cooper CL, editors. Handbook of work and health psychology. Wiley; Chichester, England: 2003. pp. 279–312. [Google Scholar]

- Glass JL, Riley L. Family responsive policies and employee retention following childbirth. Social Forces. 1998;76:1401–1435. doi:10.2307/3005840. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WB, Crouter AC. Longitudinal associations between maternal work stress, negative work–family spillover, and depressive symptoms. Family Relations. 2009;58:245–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00550.x. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandey AA, Cropanzano R. The conservation of resources model applied to work–family conflict and strain. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1999;54:350–370. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1998.1666. [Google Scholar]

- Grant-Vallone EJ, Donaldson SI. Consequences of work–family conflict on employee well-being over time. Work & Stress. 2001;15:214–226. doi:10.1080/02678370110066544. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ. Sources and conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review. 1985;10:76–88. doi:10.2307/258214. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus JH, Powell GN. When work and family are allies: A theory of work–family enrichment. Academy of Management Review. 2006;31:72–92. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG. Work–family spillover and health during midlife: Is managing conflict everything? American Journal of Health Promotion. 2000;14:236–243. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.4.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Bass BL. Work, family and mental health: Testing different models of work–family fit. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:248–262. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00248.x. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Butler AB. The impact of job characteristics on work-to-family facilitation: Testing a theory and distinguishing a construct. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2005;10:97–109. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.97. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Carlson DS, Shulkin S. Schedule flexibility and stress: Linking formal flexible arrangement and perceived flexibility to employee health. Community, Work & Family. 2008;11:199–214. doi:10.1080/13668800802024652. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Ganong L. Issues in families and health research. Family Relations. 2009;58:373–378. doi:10.1111/j.17413729.2009.00559.x. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Marks NF. Reconceptualizing the work–family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2000;5:111–126. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.1.111. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackman JR, Oldham GR. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 1976;16:250–279. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(76)90016-7. [Google Scholar]

- Härmä M. Workhours in relation to work stress, recovery and health. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health. 2006;32:502–514. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist. 1989;44:513–524. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtom BC, Mitchell TR, Lee TW, Eberly MB. Turnover and retention research: A glance at the past, a closer review of the present, and a venture into the future. Academy of Management Annals. 2008;2:231–274. doi:10.1080/19416520802211552. [Google Scholar]

- Holtom BC, Mitchell TR, Lee TW, Inderrieden EJ. Shocks as causes of turnover: What they are and how organizations can manage them. Human Resource Management. 2005;44:337–352. doi:10.1002/hrm.20074. [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Williams DR. Understanding and reducing socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in health. In: Smedley BD, Syme SL, editors. Promoting health: Intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2000. pp. 81–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal M, Baba VV. Type A behavior, components, and outcomes: A study of Canadian employees. International Journal of Stress Management. 2003;10:39–50. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.10.1.39. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8: User’s reference guide. Scientific Software International; Chicago, IL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RL, Byosserie P. Stress in organizations. In: Dunette MD, Hough LM, editors. Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Vol. 3. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1992. pp. 571–650. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek RA. Job Content Questionnaire and user’s guide. University of Massachusetts Lowell, Department of Work Environment; Lowell: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek RA. Demand/control model: A social, emotional, and physiological approach to stress risk and active behaviour development. In: Stellman JM, editor. Encyclopaedia of occupational health and safety. International Labour Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1998. pp. 34.06–34.14. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek R, Theorell T. Healthy work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL, Moen P. Rethinking the clockwork of work: Why schedule control may pay off at work and at home. Advances in Developing Human Resources. 2007;9:487–506. doi: 10.1177/1523422307305489. doi:10.1177/1523422307305489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killien MG, Habermann B, Jarrett M. Influence of employment characteristics on postpartum mothers’ health. Women & Health. 2001;33:63–81. doi: 10.1300/J013v33n01_05. doi:10.1300/J013v33n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnunen U, Geurts S, Mauno S. Work-to-family conflict and its relationship with satisfaction and well-being: A one-year longitudinal study on gender differences. Work & Stress. 2004;18:1–22. doi:10.1080/02678370410001682005. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnunen U, Mauno S. Antecedents and outcomes of work–family conflict among employed women and men in Finland. Human Relations. 1998;51:157–177. doi:10.1177/001872679805100203. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn ML, Schooler C. The reciprocal effects of the substantive complexity of work and intellectual flexibility: A longitudinal assessment. American Journal of Sociology. 1978;84:24–52. doi:10.1086/226739. [Google Scholar]

- Lee TW, Mitchell TR. An alternative approach: The unfolding model of voluntary employee turnover. Academy of Management Review. 1994;19:51–89. doi:10.2307/258835. [Google Scholar]

- MacDermid SM, Harvey A. The work–family conflict construct: Methodological implications. In: Pitt-Catsouphes M, Kossek EE, Sweet S, editors. The work and family handbook: Multi-disciplinary perspectives, methods, and approaches. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 567–586. [Google Scholar]

- Mak AS, Mueller J. Job insecurity, coping resources and personality dispositions in occupational strain. Work & Stress. 2000;14:312–328. doi:10.1080/02678370010022462. [Google Scholar]

- Morrell K. Towards a typology of nursing turnover: The role of shocks in nurses’ decisions to leave. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;49:315–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03290.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer RG, Boles JS, McMurrian R. Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1996;81:400–410. doi:10.1037/00219010.81.4.400. [Google Scholar]

- Ng TWH, Feldman DC. Re-examining the relationship between age and voluntary turnover. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2009;74:283–294. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.004. [Google Scholar]

- Oldham GR, Hackman JR, Pearce JL. Conditions under which employees respond positively to enriched work. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1976;61:395–403. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.61.4.395. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QualityMetric QM bibliography: Number of articles by disease/ condition. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.qualitymetric.com/Portals/0/Uploads/Documents/Public/SF_Bibliography_12.15.10.pdf.

- Reisel WD, Chia S-L, Maloles CM. Job insecurity spillover to key account management: Negative effects on performance, effectiveness, adaptiveness, and esprit de corps. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2005;19:483–503. doi:10.1007/s10869-005-4521-7. [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Matthews KA, Waldron I. Employment and women’s health: Effects of paid employment on women’s mental and physical health. American Psychologist. 1989;44:1394–1401. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.11.1394. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Van Rhenen W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2009;30:893–917. doi:10.1002/job.595. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J, Gupta N. Pay fairness and employee outcomes: Exacerbation and attenuation effects of financial need. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2001;74:299–320. doi:10.1348/096317901167370. [Google Scholar]

- Staines GL, Pleck JH. Nonstandard work schedules and family life. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1984;69:515–523. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.69.3.515. [Google Scholar]

- Stone EF, Hollenbeck JR. Clarifying some controversial issues surrounding statistical procedures for detecting moderating variables: Empirical evidence and related matters. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1989;74:3–10. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.74.1.3. [Google Scholar]

- Stordeur S, D’Hoore W. Organizational configuration of hospitals succeeding in attracting and retaining nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;57:45–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04095.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft C, Karlsson J, Sullivan M. Do SF-36 summary component scores accurately summarize subscale scores? Quality of Life Research. 2001;10:395–404. doi: 10.1023/a:1012552211996. doi:10.1023/A:1012552211996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LT, Ganster DC. Impact of family-supportive work variables on work–family conflict and strain: A control perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1995;80:6–15. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.80.1.6. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker P, Rutherford C. Moderators of the relationship between long work hours and health. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2005;10:465–476. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.465. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Heijden BIJM, Demerouti E, Bakker AB, the NEXT Study Group Work–home interference among nurses: Reciprocal relationships with job demands and health. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62:572–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04630.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Hulst M, Geurts S. Associations between overtime and psychological health in high and low reward jobs. Work & Stress. 2001;15:227–240. doi:10.1080/026783701110.1080/02678370110066580. [Google Scholar]

- Van Steenbergen EF, Ellemers N. Is managing the work–family interface worthwhile? Benefits for employee health and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2009;30:617–642. doi:10.1002/job.569. [Google Scholar]

- Voydanoff P. The effects of work demands and resources on work-to-family conflict and facilitation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:398–412. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00028.x. [Google Scholar]

- Voydanoff P. Consequences of boundary-spanning demands and resources for work-to-family conflict and perceived stress. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2005;10:491–503. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.491. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. doi:10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and interpretation guide. New England Medical Center, Health Institute; Boston, MA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wayne JH, Grzywacz JG, Carlson DS, Kacmar KM. Work–family facilitation: A theoretical explanation and model of primary antecedents and consequences. Human Resource Management Review. 2007;17:63–76. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2007.01.002. [Google Scholar]

- Wegge J, van Dick R, Fisher GK, Wecking C, Moltzen K. Work motivation, organizational identification, and well-being in call centre work. Work & Stress. 2006;20:60–83. doi:10.1080/02678370600655553. [Google Scholar]

- Wells JD, Hobfoll SE, Lavin J. When it rains, it pours: The greater impact of resource loss compared to gain on psychological distress. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:1172–1182. doi:10.1177/01461672992512010. [Google Scholar]