Abstract

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most significant cause of pediatric respiratory infections. Palivizumab (Synagis®), a humanized monoclonal antibody, has been used successfully for a number of years to prevent severe RSV disease in at-risk infants. However, despite intense efforts, there is no approved vaccine or small molecule drug for RSV. As an enveloped virus, RSV must fuse its envelope with the host cell membrane, which is accomplished through the actions of the fusion (F) glycoprotein, with attachment help from the G glycoprotein. Because of their integral role in initiation of infection and their accessibility outside the lipid bilayer, these proteins have been popular targets in the discovery and development of antiviral compounds and vaccines against RSV. This review examines advances in the development of antiviral compounds and vaccine candidates.

Keywords: antiviral, attachment glycoprotein, fusion glycoprotein, respiratory syncytial virus, therapeutic, vaccine, antiviral drug

INTRODUCTION

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) remains the most significant cause of pediatric respiratory infections and results in 90,000 emergency hospitalizations in the U.S. and 160,000 deaths worldwide each year, mostly in the developing world where access to supportive healthcare is limited (see also article by Hall, this issue)[1–3]. Adults and infants suffering maladies such as immune deficiencies [4–6], congenital heart defects [7, 8], chronic lung ailments such as cystic fibrosis [9], malnutrition [10], or premature birth [11] are at particularly high risk for developing severe RSV disease [12] in the lower respiratory tract, bronchiolitis and pneumonia. RSV infects individuals repeatedly throughout life [13] and causes significant disease in the elderly, second only to influenza virus in non-epidemic years [14, 15] (see also article by Walsh and Falsey, this issue). Because of these risks, RSV has been the target of intensive vaccine and antiviral drug development efforts [16].

In developed countries, many at-risk infants are treated prophylactically with palivizumab (Synagis®), a humanized monoclonal antibody (mAb) developed by MedImmune, LLC, and also sold through Abbott Laboratories. Repeated treatment with this mAb, one injection per month for the 5 winter months of the infant’s first two years, results in a 55% reduction in hospital admissions [17]. Palivizumab is currently the only option widely used to prevent severe RSV disease in at-risk infants, but because it is costly and requires monthly administration by medical staff during RSV season, it is not a practical treatment for at-risk infants in many countries [18]. The small molecule drug, ribavirin, is the only antiviral drug approved for treatment of RSV disease, but its use has largely been discontinued due to significant doubts concerning its efficacy in vivo [19, 20].

No vaccine is currently available to protect against RSV disease. Vaccine development has been approached with caution due to the failure of the initial, formalin-inactivated RSV vaccine in the 1960’s [3, 21, 22]. Although that vaccine stimulated the production of antibodies against the F protein in recipients, the antibodies did not inhibit fusion and were not protective [23]. Vaccinees remained susceptible to RSV infections, displaying an increased frequency of lower respiratory tract disease that resulted in a high hospitalization rate and two infant deaths. Pathology analysis of these two infants found a high level of inflammation in the lungs, including infiltrating eosinophils [21]. Eosinophilia is indicative of a TH2 response, suggesting that the vaccine had primed recipients for a TH2 immune response, leading to enhanced inflammation and disease pathology [24]. Experiments in mice were consistent with this idea [25–28]. Another factor possibly linked to the enhanced disease is that anti-RSV antibodies produced by the recipients following vaccination formed immune complexes during subsequent natural infection [29]. The results of this vaccine trial have strongly shaped current RSV vaccine development, such that the only vaccines under consideration for infants and children are live, attenuated vaccines (see the article by Teng in this issue for more details of RSV vaccine development).

There is a great need for an effective vaccine and for antiviral drugs against RSV, and considerable effort has focused on these objectives, so far without an approved product. Most vaccines and drugs under development target the major glycoproteins of RSV: the F and G glycoproteins. These glycoproteins are responsible for attaching the virion to a host cell and fusing its membrane with the membrane of the cell. In this review, we will evaluate recent advances in the development of vaccines and antiviral agents against the surface glycoproteins of RSV, as well as against other targets.

RSV BIOLOGY

RSV is a member of the Pneumovirinae subfamily of the Paramyxoviridae family within the order Mononegavirales. It contains a 15 kb single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome with 10 genes that encode 11 proteins. The RNA genome (and antigenome) is covered by the nucleoprotein (N), forming a helical nucleocapsid upon which the polymerase (L) protein, phosphoprotein (P) and the M2-1 protein sit. All four of these proteins are required for mRNA transcription. M2-1 is an anti-termination protein that is required for transcription but not for replication. The N protein is the major protein of the RSV nucleocapsid and remains bound to the viral genomic RNA during both replication and transcription [1].

RSV is an enveloped virus, and like all enveloped viruses, it must attach to a target cell and fuse its membrane with the cell membrane to deliver the viral genome to the cytoplasm and initiate infection. Two of its three transmembrane surface glycoproteins accomplish fusion, the G and F glycoproteins. The G protein is the main viral attachment protein [30], although the F protein also displays some attachment function [31]. The F protein is solely responsible for membrane fusion [31]. The SH protein attenuates apoptosis in the infected cell [32] and forms a pentamer that may function as a channel for cations [33].

The G protein has no sequence similarity to the attachment glycoproteins of viruses in the other subfamily, Paramyxovirinae, although like these others, it is a type II integral membrane protein [30], anchored in the membrane by its N-terminus. It facilitates attachment of the virus to the surface of cultured immortalized cells by binding to glycosaminoglycans, primarily heparan sulfate [34–38]. The G protein also facilitates RSV infection of primary well differentiated human airway epithelial (HAE) cultures. RSV infects primarily the ciliated cells in these cultures, entering from the apical surface [39]. But, since heparan sulfate is not detectable on their apical surface [40], the RSV receptor on airway cells is likely to be a different molecule. The G protein is also produced in a secreted form that may act as a decoy to sequester anti-G antibodies and to modulate lymphocyte migration, enabling more efficient virus infection and spread [41].

The cell-associated G protein is 90 kDa in molecular mass, 60% of which is carbohydrate. Most of this carbohydrate is O-linked to the protein, similar to the mucins [30]. The molecular mass of the G protein varies somewhat depending on the cell line that produces it, as a result of differences in glycosylation, cleavage or other modifications [42, 43]. Its cleavage in Vero cells by an unknown protease removes the C-terminus and inactivates its attachment function [43]. And G protein produced in well differentiated HAE cultures is much larger [43].

The structure of the G protein has not yet been solved. Its unglycosylated central region contains 4 cysteines that form disulfide bonds in a cysteine noose pattern [44]. NMR analyses of this region have identified loop structures [45, 46] that are similar to a domain in the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) [45]. And the 4 cysteines of the G protein are in the same position as the 4 cysteines in this TNFR domain [45].

The F protein trimer is responsible for fusing the viral envelope with the host cell plasma membrane [47–49]. The Pneumovirinae F protein is unique among paramyxoviruses in that it is the only glycoprotein necessary for cell-cell fusion [47] as well as for infection of cultured, immortalized cells [31, 47, 50]. However, infection is not as efficient or productive as it is with a virus containing the G protein, probably because the G protein enhances attachment to the target cell.

The RSV F protein is a type I glycoprotein whose F0 monomer is modified by the addition of either 5 or 6 N-linked glycans (depending on the strain) and assembled into a trimer in the endoplasmic reticulum. During passage through the Golgi, these glycans mature and the protein is cleaved by a furin-like enzyme in two places, releasing a 27 amino acid (aa) peptide with two or three attached glycans [51, 52]. The resulting F protein is composed of the N-terminal F2 protein linked by two disulfide bonds to the transmembrane F1 protein (Fig. 1). All paramyxovirus F proteins have a disulfide bond at the top of the pretriggered F protein that links the F1 and F2 subunits. But, a second disulfide bond, located at the bottom of the head is unique to and characteristic of members of the Pneumovirinae subfamily. The second cleavage site, and the resulting release of pep27, is unique to the RSV F protein [51, 52]. The highly hydrophobic fusion peptide resides at the cleavage-created N-terminus of the F1 protein. Once cleaved, the RSV F protein is fully active. It appears on the cell surface and from that position is able to cause cell-cell fusion, or to be incorporated into virions, where it causes virion-cell fusion, an essential step that initiates infection.

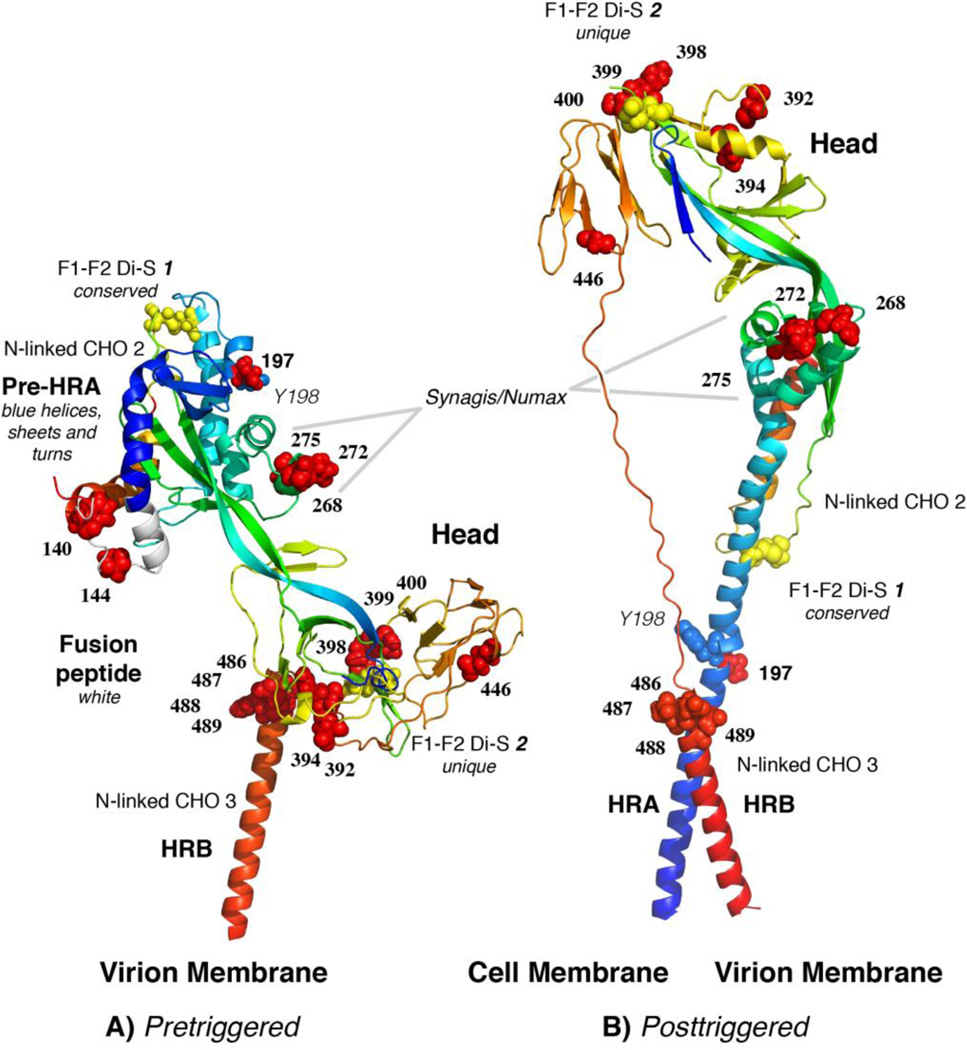

Figure 1.

Monomer model of the pretriggered (A) RSV F protein based on the crystal structure of the pretriggered PIV5 F protein, and the crystal structure of the posttriggered RSV F protein (B) (PDB structure 3RRR) [57, 58]. We have maintained the HRB domain (red α-helix) in approximately the same position in both models, as a fixed reference point. Following triggering, the pre-HRA domain (blue in A) becomes one long α-helix (blue in B), inserts its N-terminal fusion peptide (white in A) into the target membrane and folds back (B), bringing the virion and cell membranes together. The fusion peptide was not resolved in the posttriggered structure. During this fold-back, the “Head” domain maintains its position relative to HRA, but rotates approximately 180 degrees, bottom to top, relative to HRB. This rotation causes the peptide that connects HRB to the Head to wind off the Head. Two of the three N-linked glycosylation sites are indicated. The third N-linked site would be at the N-terminus of F2 (on the surface of the “Head” region) if the preceding amino acid of F2 had been visualized in the PIV5 F protein pretriggered structure. Cysteines, all of which are involved in disulfide bonds appear as yellow balls. Drug-resistant mutations appear as red balls. Residues 140 and 144 are not present in the posttriggered structure, because this region of the fusion peptide (the 9 N-terminal residues) were deleted from the nucleotide sequence to prevent aggregation of the posttriggered form. In addition, the fusion peptide was not resolved. Residue Y198 is presented as blue spheres.

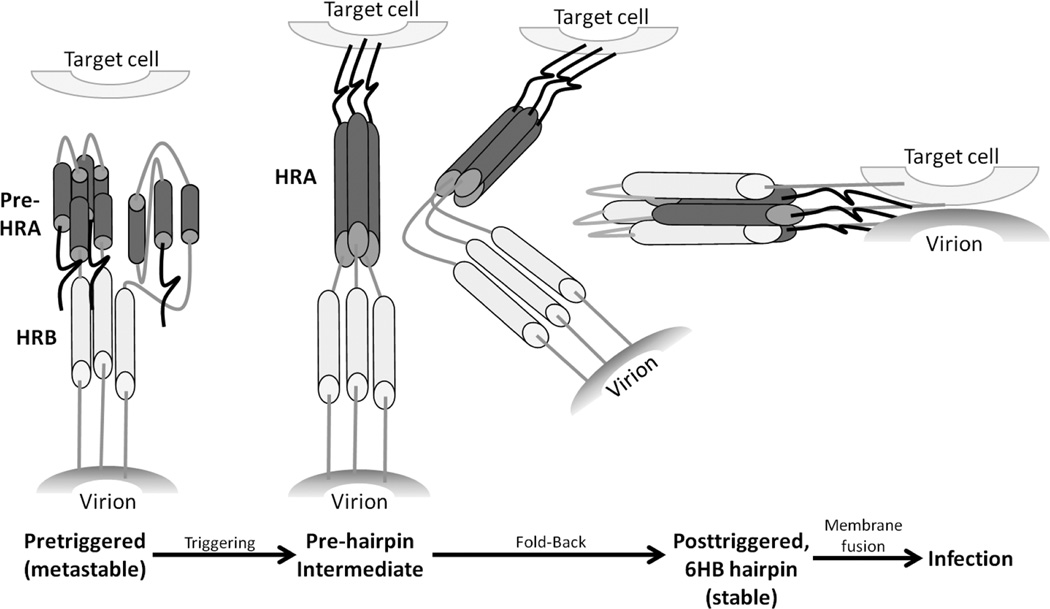

The paramyxovirus F protein trimer on the cell surface or in the virion is in a “metastable” pretriggered form, like a compressed spring, waiting to be triggered [53, 54]. Following a triggering event, it refolds into the posttriggered form with its signature 6-helix bundle, bringing the viral and cellular membranes together and causing them to fuse. For structural analysis, the F protein has been produced in a soluble form that lacks its transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains, thereby avoiding aggregation that would be caused by the hydrophobic transmembrane domain. The crystal structure of the posttriggered RSV F protein was recently solved by two groups [55, 56] and is presented in Fig. 1B. Its structure is similar to the previously solved human parainfluenza virus 3 (hPIV3) posttriggered structure [57]. The pretriggered RSV F protein structure has not yet been solved, but the pretriggered structure of the hPIV5 F protein has [57, 58]. To stabilize the hPIV5 soluble F protein, its C-terminus was fused to a self-trimerizing peptide.

We have modeled the pretriggered RSV F protein form by threading the RSV sequence through the PIV5 structure (Fig. 1A). Details of this model will be submitted for publication shortly (Chaiwatpongsakorn, S., Ray, W., Costello, H.M., and M.E. Peeples, manuscript in preparation). Upon triggering, three short α-helices (blue, in the upper left region of Fig. 1A) consolidate into one very long α-helix (blue, Fig 1B), thrusting the hydrophobic fusion peptide at its N-terminus (white, on the left side of the molecule, Fig. 1A) into the target cell membrane, thereby linking the two membranes. The resulting “pre-hairpin intermediate,” shown in the conceptual cartoon in Fig. 2, folds back on itself to form the 6-helix bundle, bringing the two membranes together in the posttriggered form and initiating fusion. During the transition from the pretriggered to the posttriggered conformation, the central “Head” region of the F protein (Fig. 1A) remains relatively constant. It is not included in the cartoon in Fig. 2 for simplicity. The highlighted amino acids on the RSV F protein (Fig. 1) indicate drug-resistant mutations in the F protein of viruses grown in the presence of each drug and will be described below. The same drug-resistant mutations are displayed on the RSV posttriggered structure determined by McLellan [56] (Fig. 1B).

Figure 2.

Cartoon of dynamic regions of the F protein that refold to initiate fusion. The three N-terminal α-helices in pre-HRA are connected by two non-helical peptides in the pretriggered form. Upon triggering these non-helical connecting peptides refold into α-helices, completing the long HRA α-helix (dark gray) and in the process thrust the F1 N-terminal fusion peptide into the target cell membrane. HRA trimerizes, the molecule folds in half, and the HRB α-helices (light gray) insert into the grooves on the surface of the HRA trimer forming the stable 6-helix bundle (6HB). As a result, the virion and cell membranes are brought together and initiate membrane fusion. The “head” region of the F protein does not rearrange during the triggering and refolding events and, therefore, is not represented in this cartoon.

The mechanism by which these drugs disrupt F protein function is difficult to determine, but there are several obvious possibilities. A drug could induce premature triggering, prevent triggering, disrupt movements involved in refolding, or prevent formation of the final posttriggered 6-helix bundle conformation. Which of these events are disrupted by each drug is not known. We have recently produced a ‘soluble’ RSV F protein that lacks its transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains and is in the fully cleaved, pretriggered form. We have also identified conditions that cause it to trigger, refolding into its posttriggered form [59]. This soluble F protein will allow us to ask questions about the mechanism of action of antiviral drugs targeting the F protein.

The F and G glycoproteins are highly immunogenic and most, if not all, RSV-neutralizing antibodies are raised against these two proteins [60, 61]. Most antiviral compounds that have been discovered target the F protein, even though these compounds were identified by screening chemical libraries for their ability to block RSV infection, highlighting the importance of the F protein in infection and as a target for antivirals. The essential role of the F protein in initiating RSV infection, its availability on the outer surface of the viral envelope, its crucial function in membrane fusion, and its dramatic conformational changes that cause membrane fusion, make the F protein the most potent target for RSV antiviral drug development.

ADVANCES IN RSV ANTIVIRAL DRUG DEVELOPMENT

Antibodies targeting RSV

Palivizumab and Motavizumab

The humanized mAb palivizumab (Synagis®, MedImmune) targets the fusion (F) glycoprotein [62, 63], inhibiting fusion but not attachment [64]. Motavizumab (Numax®, MedImmune), a second generation of palivizumab with much greater binding and neutralizing activity was subsequently developed by affinity maturation in vitro [65]. The crystal structure of motavizumab complexed with its peptide binding site from the F protein (position indicated in Fig. 1) had suggested that although this neutralizing mAb would be able to bind to the pretriggered monomer [66], its binding site would be partially hidden by the neighboring monomer in the native trimer. This prediction was based on the crystal structure of the pretriggered parainfluenza virus 5 F protein. Recently, two crystal structures of the posttriggered RSV F protein were published [55, 56]. They revealed that the palivizumab/motavizumab binding site is available for antibody binding in the posttriggered structure. Swanson, et al., [55] further suggested that this antibody-binding site is likely to be available in the pretriggered F protein since the structure and orientation of this domain does not change relative to its neighboring region when the PIV3 posttriggered F protein and the PIV5 pretriggered F protein are compared. Questions over the comparative potency of motavizumab relative to palivizumab and concerns over injection site reactions led the FDA to recommend that motavizumab not be licensed for prophylactic use [67]. Motavizumab has recently been tested in a clinical trial for its efficacy in the treatment of severe RSV disease [68], but the results have not yet been published.

RI-001

This high titer, human immunoglobulin against RSV was developed by ADMA Biologics, Inc. The immunoglobulin was isolated from otherwise healthy human adults following RSV infection. It was effective in treating three immunocompromised patients with lower respiratory tract RSV infection [69]. A phase II trial for this immunoglobulin preparation has been completed, but the results have not yet been published [70].

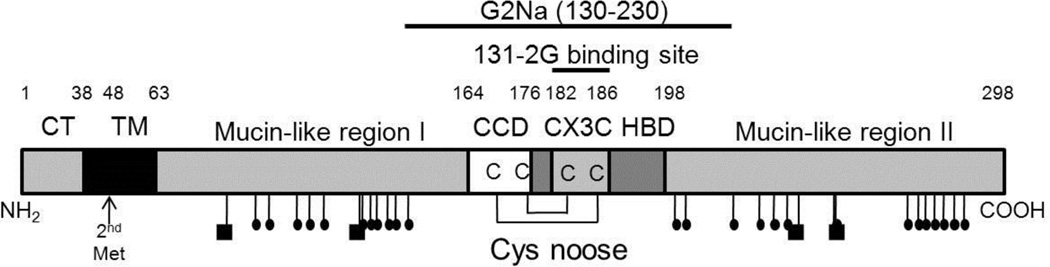

mAb 131-2G

This non-neutralizing mAb against the G protein of RSV inhibits the G protein from binding to cells expressing the CX3C chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1) and, therefore, appears to bind near the CX3C chemokine motif in the central region of the G protein (Fig. 3) [71–74]. Purified G protein induces leukocyte chemotaxis in vitro, and mAb131-2G inhibits this activity [75, 76]. Administration of mAb 131-2G to mice one day before RSV inoculation reduces pulmonary inflammation [71–74] suggesting that it may decrease inflammation and pathogenicity if used prophylactically [77]. In addition to reducing inflammation, mAb 131-2G also facilitates viral clearance in mice [74, 77, 78], so it is possible that the enhanced viral clearance was responsible for the observed reduction in inflammation. Regardless of the mechanism, such a mAb might be a useful complement to palivizumab, for protecting at-risk infants [78].

Figure 3.

Cartoon of the 298 amino acid long RSV G protein showing the N-terminal location of its cytoplasmic domain (CD) and transmembrane domain (TM), two mucin-like regions with their N-linked (squares) and O-linked (small ovals) glycans, and central cysteine noose which contains the 4 conserved cysteines, the central conserved domain (CCD), and the CX3C domain, followed by the heparin-binding domain (HBD). The position of the mAb 131-2G binding site and the peptide included in the experimental G2Na vaccine are indicated. The position of the second Met that is used to initiate translation of a truncated form of the G protein is also indicated. This form is proteolytically cleaved to remove its truncated TM domain and released from the cell as soluble G protein.

Small Molecules with antiviral activity against RSV

Compounds that bind to Y198 in the F protein

Three of the most studied RSV small-molecule antivirals have been found to select similar drug-resistant mutants (Table 1) indicating that they target the same region in the RSV F protein. We will discuss each briefly, followed by a discussion of their possible mode of inhibition.

Table 1.

Mutations Selected by RSV Antivirals

| Drug | Company/Developer | Resistant Mutants | Ref. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAb | |||||||

| palivizumab | Medimmune/AstraZeneca | N268I K272Q,M,N,T,E, S275F,L |

[230] [231] [232] |

||||

| F Drugs (Y198 binders) | Fusion Peptide | HRA | (392–394) | (398–400) | (486–489) | ||

| BMS-433771 | Bristol-Myers Squibb | F140I V144A |

D392G K394R |

D489Y | [79] | ||

| VP-14637 | ViroPharma; RSVCo | T400A | D486E F488I, V, Y, L (+N517I) D489Y |

[86] [84] |

|||

| TMC353121 (Improved upon JNJ2408062/R1 70591) | Janssen Research Foundation; Tibotec/Johnson & Johnson | S398L S398L (±K394R) K399I |

D486N E487D D489Y |

[89] [93] [84] [85] |

|||

| P13 | Lundin, et al. | N197T | T400I | [137] | |||

| C15 | Lundin, et al. | D489G | [137] | ||||

| Other F Drugs | |||||||

| RFI-641 (CL-309623) and CL-387626 | Wyeth | G446E | [84] | ||||

| BTA-9981 | Biota; MedImmune/AstraZeneca | None reported | |||||

| Peptides T-67 (HRA) T-118 (HRB) |

Trimeris | None reported | |||||

| G Drug | |||||||

| MBX-300 | Microbiotix | L97P, F101L, I107T, I114T F163P, F165L, F168S, F170S, I189T L215P F265L, L274P |

[114] | ||||

| N Drug | |||||||

| RSV604 | Arrow; Novartis | N105D, K107N, I129L, L139I | [123] | ||||

| siRNA | |||||||

| ALN-RSV01 | Alnylam | None reported | |||||

| ALN-RSV02 | Alnylam | None reported | |||||

BMS-433771

Bristol-Myers Squibb identified the fusion inhibitor BMS-233675 by screening a chemical library for compounds neutralizing RSV infection, and modified it to generate the orally-active and bioavailable azabenzimidazole molecule BMS-433771 [79–81]. BMS-433771 interacts with the F protein and does not inhibit attachment [82]. It was effective in inhibiting RSV infection of BALB/c mice when a single dose was administered prior to RSV inoculation, but not when administered 1 h after exposure [80], suggesting that it might be useful prophylactically but not therapeutically. Despite these promising results, BMS-433771 was not developed further for clinical testing due to realignment of company priorities [83].

VP-14637

ViroPharma identified a lead compound, VP-14637, from a panel of low molecular weight compounds in a HEp-2 cell-based high-throughput virus neutralization screen. It is a triphenolic compound with potent activity that targets the RSV F protein [84–87]. The initial clinical trials of VP-14637 were discontinued and VP-14637 was sold to MicroDose Therapeutx, who is continuing to develop VP-14637 with Gilead [88].

TMC353121

In a screen of 130,000 compounds for the ability to block RSV infection, Johnson & Johnson/Tibotec discovered R170591 (JNJ-2408068) [89–91]. Although extremely potent when tested in both tissue culture and the lungs of cotton rats, JNJ-2408068 was found to have long tissue retention, making it unsatisfactory for further development as an antiviral compound [90, 92]. Lead optimization guided by molecular modeling resulted in a morpholinopropyl derivative, TMC353121, which retained the potency of its predecessor, but lacked its long tissue retention [90, 91]. TMC353121 inhibits both virus-cell and cell-cell fusion in vitro, and maintains 50% effectiveness when added to cells as late as 15 h post-inoculation [93]. In recent studies with BALB/c mice, TMC353121 was effective in reducing viral load and pathology in the lungs even when administered as late as 2 days post-inoculation [94]. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies of TMC353121 in cotton rats infected with RSV found the effective dose to be more than 2,000 fold higher than that required in cultured cells (0.07 ng/ml), partly because of activity lost through binding to serum proteins [91, 95]. Johnson & Johnson/Tibotec continues to pursue TMC353121.

Mechanism of action for the Y198-binding group of compounds

All three of these compounds selected viral mutants in the aa 486–489 region of the F protein and therefore are likely to bind to the F protein similarly. However, a photoreactive, radiolabeled analog of BMS-433771 did not identify 486–489 as the attachment site of the compound. Instead, BMS-433771 cross-linked to Y198 in the F protein [96]. In a crystal structure of the RSV 6-helix bundle, TMC353121 was found attached to Y198 [93]. Both experiments clearly identify Y198 as a critical part of the binding site for these compounds.

In the pretriggered F protein model, Y198 is the central amino acid in the middle α-helix of the pre-HRA domain (Fig. 1A). Since Y198 from each monomer faces a central pore in the top of the pretriggered trimer, we hypothesize that it could be involved in triggering the F protein. Interestingly, none of the RSV mutants selected by these drugs were in Y198, suggesting that it plays an essential role in the function of the F protein (Table 1). We have recently confirmed the importance of Y198 by showing that the Y198A mutation results in an F protein incapable of fusion even though it reaches the plasma membrane (Chaiwatpongsakorn, S., Ray, W., Costello, H.M., and M.E. Peeples, manuscript in preparation).

The 486–489 mutation site shared by drug resistant mutants selected with all three of these compounds is in the HRB α-helix, at a position that would be very close to Y198 in the posttriggered 6-helix bundle (Fig. 1B). These changes may have enlarged the hydrophobic space between HRA and HRB in this region enabling the compounds to bind without disrupting 6-helix bundle formation, thereby allowing membrane fusion to occur [81, 96]. In this scenario, these compounds would likely bind to Y198 during refolding, probably following the extension and trimerization of HRA but preceding or concomitant with intercalation of the HRB helices that complete 6-helix bundle formation [82]. In the co-crystallized 6-helix bundle, TMC353121 bound to both the HRA and HRB peptides, within a hydrophobic pocket [93]. VP-14637 and BMS-433771 have also been suggested to bind to this hydrophobic pocket [85, 86, 93, 96]. Interestingly, TMC353121 did not prevent 6-helix bundle formation, but it distorted its conformation. However, this distortion is limited to the membrane distal end of the 6-helix bundle [93]. It is unclear how a local distortion some distance from the membranes could prevent fusion without preventing 6-helix bundle formation.

Following selection with TMC353121 or VP-14637, viral mutants in two additional regions of the “head” (aa 392–394 and aa 398–400) were found (Fig. 1). BMS-433771, in addition, selected mutations in the fusion peptide (aa 140 and 144). These three groups of mutations are a great distance from the 6-helix bundle in the post-triggered F protein and would be unlikely to enlarge the hydrophobic pocket to accommodate binding of a drug to Y198. So in these mutants, the compounds would still be able to bind to Y198, thereby distorting the 6-helix bundle. How, then, could these mutants avoid drug inhibition of F protein function? An alternative explanation is that all of the resistant mutants selected with these compounds destabilize the F protein in some fashion, such that the F protein is triggered randomly, without the need for its normal, specific trigger. If so, the pretriggered form of all of these F mutants would be predicted to be less stable and this possibility could be tested.

Other compounds active against the F protein

RFI-641

Wyeth-Ayerst Research screened 20,000 compounds in a virus neutralization assay to find novel inhibitors of RSV. They identified two, a stilbene and its more active biphenyl analogue, CL-387626. Both compounds are fluorophores and displayed band narrowing and a blue shift in the presence of the F protein. These changes indicated a less polar environment for the compounds and are evidence of direct binding to the F protein [97]. By modifying the biphenyl analog, this group identified a more potent inhibitor, RFI-641, a biphenyl triazene [98, 99]. Both compounds neutralized RSV strain A2 and cp-52, an RSV mutant with F as its only glycoprotein [50, 100], confirming that the target of both drugs is the F protein [101, 102]. Although CL-387626 was ineffective when given after infection to cotton rats [103], RFI-641 reduced viral loads in African green monkeys treated by inhalation with the compound even when it was administered 12 and 24 h after RSV inoculation [99, 104]. A drug-resistant mutant, G446E, has been isolated in the F protein, confirming its selective pressure on this protein [84] (Table 1, Fig. 1). RFI-641 is, however, not presently being pursued [84].

BTA9881

Biota completed a phase I clinical trial of a small molecule imidazoisoindolone derivative, BTA9881, that inhibited F protein function [105]. But further study was halted due to a poor safety profile in humans [106]. Its structure, drug resistant mutants or mechanism of action have not been reported.

Peptide analogues

Trimeris, Inc. showed that peptide analogues of the HIV-1 gp41 protein HRA and HRB domains have antiviral activity [107–109]. Their 36 amino acid HRB analog, enfuvirtide fusion inhibitor, was approved by the US Food & Drug Administration is marketed as Fuzeon®. It is used primarily to treat patients infected with multi-drug-resistant HIV. Trimeris replicated this approach for several paramyxoviruses, RSV, PIV3, and measles virus [110]. For RSV, peptide analogues of the HRB domain of the F protein (T-118; aa 488–522) were found to be fusion inhibitors [107, 110], although not as potent as the HIV-1 T-20 [108–110]. A smaller version of the T-118 HRB peptide, F478–516, is effective against RSV when present during membrane fusion [82], consistent with the suggestion that this peptide binds to the HRA trimeric coil, preventing intercalation of the protein’s own HRB helices. The fact that enfuvirtide is an effective drug against HIV infection supports the notion that a peptide derived from the HRB of the RSV F protein could have a therapeutic effect during active infection. However, Trimeris is not presently continuing work on the RSV peptides, perhaps because of the high cost of manufacture, necessity for parenteral (intramuscular) administration [111, 112].

The G protein as a target for antivirals

MBX-300

This molecule (originally called NMSO3) was pursued by Microbiotix. It is a negatively-charged sulfated sialyl lipid with four sulfate groups that is thought to inhibit attachment by inhibiting electrostatic binding [113]. RSV mutants resistant to MBX-300 have mutations across the G protein (Table 1), making it difficult to determine where it binds. Eight of these mutations are in the two mucin-like regions, and half of these are mutations to Pro, which would change the geometry of these regions, and possibly induce global changes in the conformation of the protein. Three mutations (F165L, F168S, F170S) are in the central conserved region of the G protein, long considered to be its likely receptor binding site, and all three remove a Phe. Another mutation (I189T) is in the heparin binding domain [114, 115]. This domain enables attachment to heparan sulfate, a negatively charged molecule on the surface of immortalized, cultured cells [31, 36, 37, 116]. MBX-300 has been shown to be less cytotoxic than ribavirin and to have stronger antiviral potency against both laboratory strains and clinical isolates, in both cultured cells and in cotton rats [113]. MBX-300 is not specific for RSV as it also inhibits several other viruses, including human metapneumovirus, human rotavirus, human immunodeficiency virus 1, and adenovirus [117–120].

We have found that the G protein, is critical for infection of primary well differentiated HAE cultures and that loss of its C-terminus results in the loss of this function [43]. We have also found that RSV infects primarily ciliated cells in these cultures and that, during differentiation in culture, susceptibility of these cultures to infection parallels the appearance of cilia [39]. Identification of the RSV receptor on these cells and the site on the G protein that binds these cells will provide a new target for the development of antivirals against RSV.

Compounds active against other viral targets

RSV604

Arrow Therapeutics identified several possible RSV antiviral compounds in a screen of 20,000 compounds in viral neutralization and ELISA assays, including 1,4-benzodiazepine [121]. RSV604 was developed through chemical optimization of these compounds [122]. Resistant mutants had amino acid changes in the N-terminal end of the N protein, K105D, K107N, I129L, and L139I, indicating that the N protein is the target of these compounds [121, 123]. RSV604 inhibits RSV infection in cultured cells and in an in vitro human airway epithelial model [39, 123]. Following Phase I clinical trials [124] Novartis purchased the rights to this compound but is presently not continuing its development [125].

ALN-RSV01

The first virus reported to be susceptible to control by siRNA both in cell culture and in mice was RSV [126–128]. Alnylam Pharmaceuticals has developed an siRNA, ALN-RSV01, directed against a conserved region of RSV N protein mRNA. It is the first siRNA to be tested in humans against a microbial pathogen [129]. This siRNA was determined to be the most potent antiviral among a panel of 70 siRNAs targeting the RSV N, P, and L genes, as evaluated by its ability to inhibit virus production in cultured cells. ALN-RSV01 was also able to inhibit RSV infection in BALB/c mice [130]. It has been found to be safe and effective in healthy adults [129, 131] and is currently in Phase II clinical trials [131, 132]. ALN-RSV01 was recently considered for support for continued development by two major pharmaceutical companies but was declined by both [133, 134]. However, Alnylam is continuing its partnership with Cubist Pharmaceuticals to develop siRNA drugs [135, 136], including a second generation siRNA against RSV, ALN-RSV02, intended for use in pediatric patients [136].

Other promising developments toward RSV antiviral drugs

Ongoing development of antiviral compounds targeting RSV has yielded some new candidates. In a screen of over 16,000 compounds, two novel benzenesulfonamide-based compounds targeting the F protein, P13 and C15, were discovered. A P13-resistant mutant contained a N197T mutation within the HRA region [137]. N197 is the neighbor of Y198 (Fig. 1), the residue shown to bind the F protein inhibitors BMS-433771 and TMC353121, and likely VP-14637, as described above. However, none of those compounds resulted in selection of a mutation close to Y198 in the primary sequence. P13 may bind to the same α-helix but on a neighboring face. In any case, this mutant confirms the importance of this region in HRA, but suggests that N197 is not essential while Y198 is. We have similarly found that N197 (in strain A2) can be mutated to alanine without loss of fusion activity (Chaiwatpongsakorn, S., Ray, W., Costello, H.M., and M.E. Peeples, manuscript in preparation). Another P13 resistant mutant, T400I, and a C15 resistant mutant, D489G, were also isolated. These mutants are located in the head of the RSV F protein, in two regions where mutants resistant to the Y198-binding drugs have also been isolated. This finding indicates further that these two novel compounds may work in a similar, though perhaps not identical manner to the compounds BMS-433771, VP-14637, and TMC353121.

A less specific approach has been taken by another group that has used palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidylglycerol (POPG) to inhibit both RSV infection and the host inflammatory response in cultured cells and in mice. In cultured cells, POPG seems to inhibit attachment of the virus to the cells and to inhibit viral spread [138]. Dunn, et al., have recently shown that treatment with leflunomide, an immunosuppressive therapeutic, can reduce RSV load in cell culture and in infected cotton rats [139].

Development of new or improved antiviral screening methods has also been a major endeavor, and has been met with some significant success. Park, et al., have developed a peptide binding assay based on the fluorescence polarization caused by an HRB peptide binding to the final available position in an engineered 5-helix bundle of the RSV F protein. The assay could be used to screen for compounds that inhibit 6-helix bundle formation and therefore membrane fusion [140].

Our laboratory has developed a replicon system for screening libraries of chemical compounds to identify those that inhibit the RSV RNA polymerase. We have removed the three glycoprotein genes from the full-length RSV cDNA, replacing them with a blasticidin-resistance gene, and inserted a marker gene that expresses green fluorescent protein [141]. To enhance high throughput screening, we have also inserted the Renilla luciferase gene (Malykhina and Peeples, unpublished data). A compound that inhibits genome replication or mRNA transcription reduces production of luciferase. This RSV replicon system may be able to identify compounds active against the viral polymerase (L), N, P, or M2-1, all of which are involved in viral replication and/or transcription.

ADVANCES IN RSV VACCINE DEVELOPMENT

There are significant hurdles in the development of a safe, effective RSV vaccine [142]. As described above, the formalin-inactivated vaccine trial of the 1960’s not only failed to protect, but enhanced disease in many of the recipients [3, 21, 22]. This is thought to be largely the result of an exaggerated TH2 inflammatory response upon RSV challenge [24, 28, 143], but other possibilities have been suggested (reviewed in Blanco, et al. [144]). We will review many of the approaches that have been taken toward an effective RSV vaccine, their successes and their failures. We will not spend much time on the immunological concepts and problems with RSV vaccination, or on vaccination of the newborns and infants, in general. Instead, we would refer the reader to several excellent recent reviews of these subjects [144–147].

Additional challenges in the development of an effective RSV vaccine are the immunogenicity of vaccine components in the very young who have both an immature immune system and the presence of maternal antibodies against RSV [148–151]. And in the elderly, immune senescence decreases the response to vaccines [152–154]. Furthermore, RSV infection does not induce a particularly effective immune response even in healthy people. RSV is able to infect repeatedly throughout life [155], leading to concerns over the ability of an RSV vaccine to protect. However, the goal, as Bob Chanock would often say, is a vaccine that prevents severe disease, not one that prevents RSV infection; the latter is much more difficult, perhaps impossible. Limiting RSV infection to the upper respiratory tract may be sufficient and is a reasonable goal since severe disease in a natural infection is due to lower respiratory tract infection. Finally, an RSV vaccine must not cause symptoms. Our goal here is to review vaccine approaches that have been developed over the years and novel approaches that present new possibilities.

Inactivated RSV vaccines and protein vaccines have generally not been considered for infants and children because of the enhanced disease observed in the original formalin-inactivated RSV vaccine trial and in the mouse model. Vaccine development has focused instead on live, attenuated viruses for children and subunit vaccines containing one or both of the major RSV glycoproteins, G and F, for adults. Reverse genetics has provided new tools for the construction of live attenuated vaccines with a variety of modifications.

Live, attenuated viruses and vector-based viruses as vaccine candidates

Attenuated respiratory vaccines administered intranasally can induce both mucosal and systemic immune responses, as clearly shown by the successful influenza A vaccine [156, 157]. Live, attenuated RSV is particularly attractive as a vaccine because, unlike the inactivated RSV vaccine, infection with live virus does not lead to enhanced disease pathology upon challenge [158, 159]. The many attenuated RSV viruses that have been developed and tested for their vaccine suitability have recently and thoroughly been reviewed by Schmidt [147]. Here we will just hit the highlights.

The first viable live attenuated vaccine candidate for infants was cpts248/404, with attenuation gained both from mutations that appeared during cold-passage, chemical mutagenesis and high temperature passage [160–164]. But this strain caused nasal congestion in recipients [165]. In an effort to further attenuate this candidate, the SH gene was deleted and a missense mutation (ts1030) was included in the L gene, all by reverse genetics, creating rA2cp248/404/1030ΔSH [166]. This virus induced a high antibody response in children, but much less of a response in infants. Just as importantly, it did not cause nasal congestion like its predecessor. Furthermore, the infants were protected from a second dose of the vaccine, essentially a challenge RSV infection [16]. These ongoing clinical trials are in Phase I/IIa, (MEDI-559).

Other attenuated vaccine candidates have been developed but not yet tested in clinical trials. The rA2ΔM2-2 candidate, lacking its M2-2 gene [167, 168] was immunogenic in African green monkeys and, after two doses, protective against an RSV challenge [169]. This attenuated virus, as well as rA2ΔNS1 which is lacking its NS1 gene, were highly attenuated in chimpanzees, a necessity for a pediatric vaccine [167]. Candidates rA-GBFB (G and F genes of strain B substituted for the G and F genes of the A2 strain), and rA-GBFBΔM2-2, also missing its M2-2 gene, were both attenuated and protective against an RSV challenge in African green monkeys [168].

Reverse genetics has also enabled the development of vectored vaccine candidates, such as a bivalent viral vaccine designed to protect against both RSV and human parainfluenza virus type 3 (hPIV3). It is a chimeric, bovine, bPIV3 virus, with the hPIV3 F and hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (attachment protein) genes replacing their bovine virus counterparts, and the addition of the RSV F gene (MEDI-534, MedImmune) [170–172]. A major advantage of bHPIV3 is that it is naturally attenuated in humans. While MEDI-534 was immunogenic and protective in hamsters and monkeys [172, 173], it was overly attenuated in human adults and children, inducing low antibody titers [170, 174]. Testing in seronegative infants is in Phase I/IIa trials [174, 175].

Subunit vaccines

RSV subunit vaccines, containing the F or G protein, or both, are being developed to boost immunity in adults and the elderly and protect against RSV disease. As mentioned above, subunit vaccines have not been considered for infants who do not have an established, effective immune response pattern because of the risk of enhanced disease which was seen in the initial inactivated vaccine trial.

Since the F protein is essential for RSV infection and is fairly well conserved between the two subgroups [176] compared to the G protein, which is not [115], the F protein would seem to be ideal for use as a subunit vaccine. Three similar F subunit vaccines have been developed and tested in clinical trials [177–183]. The PFP-1 vaccine developed by Lederle-Praxis Biologicals was composed of the F protein produced from RSV-infected Vero cells and isolated by immunoaffinity chromatography [184, 185]. Wyeth-Lederle subsequently developed both the PFP-2 and PFP-3 vaccines composed of the RSV F protein isolated by ion-exchange chromatography. PFP-3 was produced by a cold-passaged, temperature-sensitive mutant RSV that expressed high levels of the F protein [180–182]. The purity of the F protein in these formulations were all 90% or greater. All three PFP vaccines were administered with an alum adjuvant and all were safe in tested populations. But they induced only modest levels of serum neutralizing antibodies, or did not prevent lower respiratory tract infection [180–185].

Novavax, Inc. has recently begun a Phase I clinical trial to investigate the safety of an RSV F protein virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine [186–188]. It was found to be protective in cotton rats with no evidence of enhanced disease [189].

A vaccine developed by Sanofi Pasteur contains a mixture of RSV F, G and M proteins co-purified from infected Vero cells [190]. The RSV F and G proteins induce neutralizing antibodies and the RSV M protein may stimulate T cell responses [191–195]. It was found to be safe and immunogenic in a Phase II clinical trial in the elderly [192].

The ideal F protein vaccine would be in the pretriggered form because this is the active form of the F protein present on virions. Isolation of full-length F protein from infected or transfected cells by immunoaffinity chromatography and ion exchange chromatography expose this metastable protein to extremes of pH or ionic strength. The simplest method of producing the F protein in an easy to purify form would be in a secreted, soluble (sF) form. However, Yin et al. [58] found that simply removing the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains from the PIV3 F protein resulted in the release of posttriggered sF, as determined by EM and by X-ray crystallography. In a subsequent report, Yin et al. found that the addition of a self-trimerizing α-helix to the C-terminus of the PIV5 F protein in place of its transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains prevented triggering of the PIV5 sF protein. They used this protein to solve the structure of the pretriggered paramyxovirus F protein [57]. We have found that linking this α-helix to the C-terminus of the RSV F protein in place of the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains also stabilizes it in the pretriggered form (Chaiwatpongskorn, S. and Peeples, M.E., unpublished results). But the addition of this foreign domain was not required to prevent triggering. Simply removing the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of the sF protein resulted in the production and release of pretriggered, fully cleaved RSV sF protein [59]. By adding a 6-His tag to its C-terminus, we were able to isolate this pretriggered RSV sF protein on a Ni2+ column. We have found that the sF protein remains in its pretriggered form for at least three months (unpublished data). We have found that the sF protein can be induced to trigger by reducing the buffer molarity [59]. It is not clear whether this mode of triggering is physiologically relevant.

The specific component of the formalin-inactivated RSV vaccine that led to enhanced disease upon RSV challenge has not been identified with certainty, but the most likely candidate is the RSV G protein. Two studies have presented particularly strong evidence for the G protein. Immunization of mice with G protein purified from RSV-infected Vero cells led to a strong TH2 response upon challenge [196]. In addition, vaccination with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the RSV G protein also induced a strong TH2 response upon challenge, but removal of amino acids 193–205, part of the mucinoid II region, avoided that pathogenic response and, in fact induced protective immunity in mice implicating this region as a possible cause of the enhanced pathology [197].

As described in the Introduction, mAb 131-2G targets the central region of the G protein and prevents the CX3C motif from binding to the CX3C receptor. This mAb has been shown to prevent enhanced disease in FI-RSV-immunized mice challenged with RSV [78]. In these experiments, the mAb was injected one day before the RSV challenge and may have covered the C3XC site on the G protein of the challenge RSV, thereby preventing lymphocyte chemotaxis. An alternative possibility is that the mAb neutralized the challenge RSV in vivo, reducing or preventing infection and therefore preventing enhanced disease. The authors did not consider this possibility because mAb 131-2G does not neutralize RSV infection of Vero cells. However, the RSV G protein uses heparan sulfate as its receptor on immortalized cells. It very likely uses a different receptor on fully differentiated airway cells which do not express detectable heparan sulfate on their apical surface [40, 43]. Furthermore, the central region of the G protein, where this mAb binds, is the most likely attachment site for its in vivo receptor both because of the conserved nature of much of this region and because it is the only site on the G protein that is not covered with glycans.

A peptide vaccine, BBG2Na (aa 130–230, Fig. 3), that contains this central conserved domain of the G protein induces protective immunity in mice [143, 198–200]. BBG2Na also includes amino acids 193–205, the sequence suggested to be necessary for enhanced disease [197]. But RSV challenge of mice immunized with BBG2Na did not lead to enhanced disease. In human trials, BBG2Na was well-tolerated and showed a moderate ability to induce neutralizing antibodies in healthy, young adults [198]. However, in infant macaques, BBG2Na did not induce neutralizing antibodies, did not reduce pulmonary viral loads, and resulted in mild eosinophilia upon RSV challenge in two of four animals [201]. BBG2Na is not presently being pursued.

Recent promising developments toward an RSV vaccine

A large number of alternative RSV vaccine approaches are presently being pursued but have not yet reached clinical trials. This vibrant activity has been wide-ranging, including both RSV proteins/peptides produced in vitro for injection and viral vectors that produce RSV proteins in vivo. These multiple approaches are providing further insights into the mechanisms of immunity and the causes of enhanced immunopathology. They are also expanding the possibilities for and the likelihood of an eventual RSV vaccine. We have briefly summarized many, but not all, of these approaches below to enable comparisons.

Recombinant virus vectors expressing RSV proteins in vivo

Widjojoatmodjo, et al., found that RSV strain A lacking its G gene protected cotton rats from RSV challenge without causing enhanced disease [202], suggesting that this vaccine approach may be promising. This result was surprising because the original G-deleted RSV, a strain B mutant, had not been protective in mice or non-human primates [16, 50]. Perhaps the RSV strain difference is responsible. In our experience, a strain A RSV lacking its G protein is 10-fold less infectious for well differentiated HAE cultures than G-containing virus [43]. Poor infectivity in HAE cultures would likely reflect reduced effective titer of an attenuated vaccine in vivo. Furthermore, we found that this same strain, lacking the G gene, produced titers at least 10-fold lower than the parental virus in immortalized cell culture [31], which would reduce the efficiency of vaccine production. However, production of a G-deleted RSV in a cell line expressing the G protein might boost the virus titer and make such a vaccine feasible by enhancing its initial infection in vivo.

A number of novel vectored vaccines have been generated and tested in animals recently. A chimeric measles virus vaccine expressing the RSV F protein, administered intranasally, protected cotton rats and induced only mild inflammation upon RSV challenge; however, vaccine-enhanced eosinophilia was not evaluated [203]. A replication-deficient adenovirus expressing aa 155–524 of the RSV F protein, preceded by a signal sequence to enable secretion, administered to the nasal mucosa of mice, protected them against RSV challenge without inducing enhanced pathology [204]. This RSV F protein sequence was codon optimized to enable expression from the nucleus, a requirement for the F protein [205]. The success of this vaccine in mice is striking because the F protein fragment used excludes F2, pep27, the fusion peptide, and the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains [204] and therefore much of this F protein fragment would not be expected to be folded properly. Another adenovirus vector has been constructed with codon-optimized versions of the full-length and an anchorless RSV F protein. Both were immunogenic and protected mice against RSV challenge. BAL fluid collected from immunized and subsequently challenged mice did not indicate eosinophilia [206].

Martinez-Sobrido, et al., created a chimeric Newcastle disease virus (NDV) expressing the RSV F gene. NDV, an avian pathogen, is known to induce a robust innate immune response in infected cells, unlike the weak response induced by RSV. In mice, they found a greater immune response to the RSV F protein expressed from this vector than from RSV infection itself, and it protected from RSV challenge without immunopathology [207]. Importantly, NDV is naturally attenuated in humans and high virus titers can readily be produced in embryonated eggs.

Sendai virus (SeV), a parainfluenza virus of mice, engineered to express RSV glycoproteins, is also being developed as a vaccine. SeV expressing either the RSV G or F protein given intranasally to cotton rats protected them from an RSV challenge with no evidence of pulmonary immunopathology [208–211]. Neither RSV glycoprotein was incorporated into the budding virions [208, 209]. Other recombinant SeV-RSV expressing either the complete RSV F protein or a soluble version induced protective immunity against RSV, but these vaccines also elicited slightly enhanced immunopathology [212, 213]. These latter SeV vectors contained the F gene in the third gene position while in the former, the F gene was in the fifth position. A gene in the third position would be expressed at a higher level than a gene in the fifth position because of the polar nature of paramyxovirus gene expression and perhaps the higher level of antigen production led to the mild pathology. Sendai virus, like NDV, has the advantage of stimulating interferon and of high titer production in embryonated eggs.

Mok, et al., has produced nonpropagating Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) virus replicon particles (VRPs) that contain an RNA genome encoding the VEE replicase proteins and either the RSV F or RSV G protein. Both VRPs protected mice and rats from RSV challenge of the upper respiratory tract without causing enhanced inflammation. The RSV G protein-expressing VPR protected against lower respiratory tract RSV challenge, while the F protein VRP did not [214].

Wu, et al., have developed a DNA vaccine encoding a fragment of the F protein (residues 412–524; part of the “head” and HRB, Fig. 1) and the same F protein fragment fused to a portion the ctxA2B subunit of the cholera toxin, a potent adjuvant. DNA expressing these proteins was injected intramuscularly in mice, and the mice were subsequently challenged with RSV. Both vaccines were partially protective [215, 216].

Bacterial expression vectors are also being developed for use as T cell vaccines to protect against RSV. Strains of the mycobacterium Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) expressing either the RSV N or M2-1 protein were protective against RSV challenge in mice [217]. Expression of the N protein elicited TH1 T cell recruitment to the lungs, mediating viral clearance and reducing inflammation upon challenge [218].

RSV protein vaccines produced in vitro

VLPs are being developed as vaccines and yielding some interesting candidates. Nallet, et al., transiently expressed a codon optimized F protein in Vero cells and purified it by chromatography before inserting it into immunostimulating reconstituted influenza virosomes (IRIV). The IRIV was composed of pure lipids, the RSV F protein and the influenza HA and NA proteins. This IRIV induced the production of neutralizing anti-F antibodies in BALB/c mice, but protection against RSV challenge and vaccine-enhanced immunopathology were not assessed [219]. NDV VLPs containing the NDV NP and M proteins and the ectodomains of the RSV F and G proteins fused to the NDV F and HN transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains, respectively, have been produced from transfected cells and shown to stimulate the production of neutralizing antibodies to both the F and G proteins in mice. These immunized mice were protected from RSV challenge and did not display enhanced disease [220]. Stegmann, et al., have produced pure lipid virosomes containing RSV proteins F, G, and, to a lesser extent, M, and have shown that they induce protective neutralizing antibodies in mice and cotton rats. P3CSK4, a synthetic lipopeptide, was included in these liposomes as an adjuvant because it is recognized by TLR-2, and therefore should establish a TH1 response pattern. Immunized mice and cotton rats were protected and showed no indication of vaccine-enhanced disease upon challenge [221].

Trudel, et al., has developed a peptide vaccine composed of 14 amino acids from the central domain of the G protein (Fig. 3) (aa 174 to 187, with one mutation, C186S), cross-linked to keyhole limpet hemocyanin [222–224]. Following mucosal administration, both the hRSV peptide (adjuvanted with cholera toxin) and the bRSV G protein peptide (without adjuvant) protected BALB/c mice from challenge, though the induction of enhanced immunopathology was not determined [222]. This peptide includes the CX3C motif except for the Cys mutation and was chosen from a panel of hRSV G protein peptides for its ability to induce a protective response when administered intraperitoneally to mice [224].

Adjuvants

Because of the history of enhanced disease following the formalin-inactivated RSV vaccine, there has been interest in developing adjuvants that promote a TH1 or balanced immune response. CpG oligodeoxynucleotide, indolicidin, and polyphosphazene have been tested as adjuvants. When soluble bovine, bRSV, F protein (aa 1–522) was mixed with a combination of these adjuvants and administered to mice, the adjuvants enhanced the immune response relative to the soluble bRSV F protein alone, resulting in the production of more neutralizing antibodies and a shift from TH2 to TH1 response following bRSV challenge [225]. After challenge, much less bRSV RNA was detected in the lungs compared to unimmunized mice. This combination of adjuvants may have potential for future human RSV vaccine formulations with viral subunits. A combination of saponin QS-21 and recombinant interleukin-12 has also been shown to be a strong adjuvant for production of cell-mediated immunity and neutralizing antibodies against the RSV F protein [226].

NanoBio Corporation recently demonstrated that a nanoemulsion of water-in-oil can both inactivate RSV and function as an adjuvant in the vaccination of mice. Intranasally vaccinated mice cleared an RSV challenge to either the upper or lower respiratory tract without evidence of enhanced disease [227], suggesting that this approach has promise. NanoBio recently licensed a novel RSV antigen from the NIH for use in the development of this vaccine [228], but the composition of this antigen was not reported.

CONCLUSIONS

RSV continues to be a major cause of hospitalization for infants and of morbidity and mortality for the elderly. With the prophylactic mAb palivizumab being the only approved, effective compound against RSV, there is a great need for antiviral drugs and effective vaccines. There are significant hurdles to overcome with the development of both. Antiviral compounds must display acceptable safety, half-life, tissue targeting, and bioavailability. While the greatest need is for a drug to treat active infections, antiviral drugs could also play a prophylactic role. Likewise, palivizumab or motavizumab may have a future role in treating established disease in addition to prophylaxis.

Most antiviral drugs developed thus far target the F protein, which is essential for RSV to infect and to spread within an individual. Interestingly, three of the most thoroughly studied small molecules all bind to the same general site on the F protein that includes Y198, but none of drugs select resistant mutations in Y198. This amino acid may play a critical role for the F protein, either in initiating its conformational change or in forming its 6-helix bundle, the final step in its fusion function. One of those small molecules, TMC353121, has been shown to distort the 6-helix bundle. This small molecule continues to be pursued and may yet emerge as a useful antiviral drug. Other novel drugs under development also show promise. It is not clear whether the appearance of drug-resistant RSV variants will be a problem once an antiviral is in use. This problem has surfaced with drugs against influenza virus, another acute respiratory virus [229], suggesting that it will likely be a problem with RSV, too. If so, a combination of two or three drugs may be needed to reduce the likelihood of the appearance of drug-resistant RSV.

Attenuated and vectored vaccine development has carefully avoided candidates that cause any significant symptoms following vaccination, and even more carefully avoided vaccine-enhanced disease upon challenge. These twin limitations have made finding a live vaccine that is attenuated while remaining immunogenic very difficult. Presently, the most advanced live vaccine candidates for infants are the attenuated RSV and the chimeric bPIV-3 expressing the RSV F protein. Both should induce antibody and T cell responses to the F glycoprotein. However, only the attenuated RSV will induce T cell responses to the other 10 RSV proteins and antibodies to the G protein. The antibody response against the G and F glycoproteins is clearly important for protection, but the importance of the cytotoxic T cell response has not been studied in humans. RSV strain A lacking its G gene and vectored RSV vaccines that express the RSV F or G protein from measles virus, NDV, Sendai virus, adenovirus, and VEE have great potential but are earlier in development. Bacterial T cell vaccines are a novel approach and may allow inoculation early in life.

Subunit protein vaccines continue to have potential as vaccines for adults in whom a non-pathogenic immune response to RSV has already been established, but this response needs restimulation. The recent surge in novel RSV vaccine approaches, including the addition of novel adjuvants is encouraging, presenting additional options to the traditional approaches. The road to a protective vaccine against severe RSV disease has not been easy, but many excellent options are being explored and one or more are likely to reach this important goal for human health.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

HMC was supported by NIH National Research Service Award T32 training grants to The Ohio State University, GM068412 from NIGMS awarded to the Integrated Biomedical Science Graduate Program and AI065411 from NIAID awarded to the Center for Microbial Interface Biology (CMIB). MEP was supported by The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, NIH grant AI047213, Tibotec, and MedImmune. WCR was also supported by The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and MedImmune.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The MEP laboratory is collaborating with and partially supported by Tibotec/Johnson & Johnson. None of the authors receive any personal funds from this collaboration. MEP is a co-inventor on a patent for the RSV replicon and has received funds through Apath from licensing that technology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collins PLaJEC., Jr . Respiratory syncytial virus and metapneumovirus. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glezen P, Denny FW. Epidemiology of acute lower respiratory disease in children. N Engl J Med. 1973;288(10):498–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197303082881005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim HW, Arrobio JO, Brandt CD, Jeffries BC, Pyles G, Reid JL, Chanock RM, Parrott RH. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus infection in Washington, D.C. I. Importance of the virus in different respiratory tract disease syndromes and temporal distribution of infection. Am J Epidemiol. 1973;98(3):216–225. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogra PL, Patel J. Respiratory syncytial virus infection and the immunocompromised host. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988;7(4):246–249. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198804000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pohl C, Green M, Wald ER, Ledesma-Medina J. Respiratory syncytial virus infections in pediatric liver transplant recipients. J Infect Dis. 1992;165(1):166–169. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassis C, Champlin RE, Hachem RY, Hosing C, Tarrand JJ, Perego CA, Neumann JL, Raad II, Chemaly RF. Detection and control of a nosocomial respiratory syncytial virus outbreak in a stem cell transplantation unit: the role of palivizumab. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(9):1265–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDonald NE, Hall CB, Suffin SC, Alexson C, Harris PJ, Manning JA. Respiratory syncytial viral infection in infants with congenital heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(7):397–400. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198208123070702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner A, Begg C, Smith B, Coutts J. The influence over a period of 8 years of patterns of prescribing palizivumab for patients with and without congenitally malformed hearts, and in admissions to paediatric intensive care. Cardiol Young. 2009;19(4):346–351. doi: 10.1017/S1047951109003771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abman SH, Ogle JW, Butler-Simon N, Rumack CM, Accurso FJ. Role of respiratory syncytial virus in early hospitalizations for respiratory distress of young infants with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 1988;113(5):826–830. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adegbola RA, Falade AG, Sam BE, Aidoo M, Baldeh I, Hazlett D, Whittle H, Greenwood BM, Mulholland EK. The etiology of pneumonia in malnourished and well-nourished Gambian children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13(11):975–982. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199411000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall CB, Kopelman AE, Douglas RG. Neonatal respiratory syncytial virus infection. New. Engl. J. Med. 1979;300(393–396) doi: 10.1056/NEJM197902223000803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorburn K. Pre-existing disease is associated with a significantly higher risk of death in severe respiratory syncytial virus infection. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(2):99–103. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.139188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall CB, Walsh EE, Long CE, Schnabel KC. Immunity to and frequency of reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis. 1991;163(4):693–698. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falsey AR, Walsh EE. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly adults. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(7):577–587. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522070-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Cox N, Anderson LJ, Fukuda K. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;289(2):179–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karron RA, Wright PF, Belshe RB, Thumar B, Casey R, Newman F, Polack FP, Randolph VB, Deatly A, Hackell J, Gruber W, Murphy BR, Collins PL. Identification of a recombinant live attenuated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine candidate that is highly attenuated in infants. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(7):1093–1104. doi: 10.1086/427813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anonymous. Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants. The IMpact-RSV Study Group. Pediatrics. 1998;102(3 Pt 1):531–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevens TP, Hall CB. Controversies in palivizumab use. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(11):1051–1052. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000145759.71531.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ventre K, Randolph AG. Ribavirin for respiratory syncytial virus infection of the lower respiratory tract in infants and young children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD000181. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000181.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall CB, McBride JT, Walsh EE, Bell DM, Gala CL, Hildreth S, Ten Eyck LG, Hall WJ. Aerosolized ribavirin treatment of infants with respiratory syncytial viral infection. A randomized double-blind study. N Engl J Med. 1983;308(24):1443–1447. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198306163082403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HW, Canchola JG, Brandt CD, Pyles G, Chanock RM, Jensen K, Parrott RH. Respiratory syncytial virus disease in infants despite prior administration of antigenic inactivated vaccine. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89(4):422–434. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fulginiti VA, Eller JJ, Sieber OF, Joyner JW, Minamitani M, Meiklejohn G. Respiratory virus immunization. I. A field trial of two inactivated respiratory virus vaccines; an aqueous trivalent parainfluenza virus vaccine and an alum-precipitated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89(4):435–448. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy BR, Walsh EE. Formalin-inactivated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine induces antibodies to the fusion glycoprotein that are deficient in fusion-inhibiting activity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26(8):1595–1597. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.8.1595-1597.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lampinen M, Carlson M, Håkansson LD, Venge P. Cytokine-regulated accumulation of eosinophils in inflammatory disease. Allergy. 2004;59(8):793–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson TR, Graham BS. Secreted respiratory syncytial virus G glycoprotein induces interleukin-5 (IL-5), IL-13, and eosinophilia by an IL-4-independent mechanism. J Virol. 1999;73(10):8485–8495. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8485-8495.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson TR, Teng MN, Collins PL, Graham BS. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) G glycoprotein is not necessary for vaccine-enhanced disease induced by immunization with formalin-inactivated RSV. J Virol. 2004;78(11):6024–6032. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.6024-6032.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson TR, Varga SM, Braciale TJ, Graham BS. Vbeta14(+) T cells mediate the vaccine-enhanced disease induced by immunization with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) G glycoprotein but not with formalin-inactivated RSV. J Virol. 2004;78(16):8753–8760. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8753-8760.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waris ME, Tsou C, Erdman DD, Zaki SR, Anderson LJ. Respiratory synctial virus infection in BALB/c mice previously immunized with formalin-inactivated virus induces enhanced pulmonary inflammatory response with a predominant Th2-like cytokine pattern. J Virol. 1996;70(5):2852–2860. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2852-2860.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polack FP, Teng MN, Collins PL, Prince GA, Exner M, Regele H, Lirman DD, Rabold R, Hoffman SJ, Karp CL, Kleeberger SR, Wills-Karp M, Karron RA. A role for immune complexes in enhanced respiratory syncytial virus disease. J Exp Med. 2002;196(6):859–865. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wertz GW, Collins PL, Huang Y, Gruber C, Levine S, Ball LA. Nucleotide sequence of the G protein gene of human respiratory syncytial virus reveals an unusual type of viral membrane protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82(12):4075–4079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Techaarpornkul S, Barretto N, Peeples ME. Functional analysis of recombinant respiratory syncytial virus deletion mutants lacking the small hydrophobic and/or attachment glycoprotein gene. J Virol. 2001;75(15):6825–6834. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.6825-6834.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuentes S, Tran KC, Luthra P, Teng MN, He B. Function of the respiratory syncytial virus small hydrophobic protein. J Virol. 2007;81(15):8361–8366. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02717-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gan SW, Ng L, Lin X, Gong X, Torres J. Structure and ion channel activity of the human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) small hydrophobic protein transmembrane domain. Protein Sci. 2008;17(5):813–820. doi: 10.1110/ps.073366208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levine S, Klaiber-Franco R, Paradiso PR. Demonstration that glycoprotein G is the attachment protein of respiratory syncytial virus. J Gen Virol. 1987;68(Pt 9):2521–2524. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-9-2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feldman SA, Hendry RM, Beeler JA. Identification of a linear heparin binding domain for human respiratory syncytial virus attachment glycoprotein G. J Virol. 1999;73(8):6610–6617. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6610-6617.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hallak LK, Spillmann D, Collins PL, Peeples ME. Glycosaminoglycan sulfation requirements for respiratory syncytial virus infection. J.Virol. 2000;74(22):10508. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10508-10513.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hallak LK, Collins PL, Knudson W, Peeples ME. Iduronic acid-containing glycosaminoglycans on target cells are required for efficient respiratory syncytial virus infection. Virology. 2000;271(2):264–275. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krusat T, Streckert HJ. Heparin-dependent attachment of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) to host cells. Arch Virol. 1997;142(6):1247–1254. doi: 10.1007/s007050050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, Peeples ME, Boucher RC, Collins PL, Pickles RJ. Respiratory syncytial virus infection of human airway epithelial cells is polarized, specific to ciliated cells, and without obvious cytopathology. J Virol. 2002;76(11):5654–5666. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5654-5666.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang L, Bukreyev A, Thompson CI, Watson B, Peeples ME, Collins PL, Pickles RJ. Infection of ciliated cells by human parainfluenza virus type 3 in an in vitro model of human airway epithelium. J Virol. 2005;79(2):1113–1124. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1113-1124.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bukreyev A, Yang L, Fricke J, Cheng L, Ward JM, Murphy BR, Collins PL. The secreted form of respiratory syncytial virus G glycoprotein helps the virus evade antibody-mediated restriction of replication by acting as an antigen decoy and through effects on Fc receptor-bearing leukocytes. J Virol. 2008;82(24):12191–12204. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01604-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia-Beato R, Martinez I, Franci C, Real FX, Garcia-Barreno B, Melero JA. Host cell effect upon glycosylation and antigenicity of human respiratory syncytial virus G glycoprotein. Virology. 1996;221(2):301–309. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwilas S, Liesman RM, Zhang L, Walsh E, Pickles RJ, Peeples ME. Respiratory syncytial virus grown in Vero cells contains a truncated attachment protein that alters its infectivity and dependence on glycosaminoglycans. J Virol. 2009;83(20):10710–10718. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00986-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorman JJ, Ferguson BL, Speelman D, Mills J. Determination of the disulfide bond arrangement of human respiratory syncytial virus attachment (G) protein by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of flight mass spectrometry. Protein Sci. 1997;6(6):1308–1315. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Langedijk JP, de Groot BL, Berendsen HJ, van Oirschot JT. Structural homology of the central conserved region of the attachment protein G of respiratory syncytial virus with the fourth subdomain of 55-kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Virology. 1998;243(2):293–302. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gorman JJ, McKimm-Breschkin JL, Norton RS, Barnham KJ. Antiviral activity and structural characteristics of the nonglycosylated central subdomain of human respiratory syncytial virus attachment (G) glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(42):38988–38994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106288200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barretto N, Hallak LK, Peeples ME. Neuraminidase treatment of respiratory syncytial virus-infected cells or virions, but not target cells, enhances cell-cell fusion and infection. Virology. 2003;313(1):33–43. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamb RA, Joshi SB, Dutch RE. The paramyxovirus fusion protein forms an extremely stable core trimer: structural parallels to influenza virus haemagglutinin and HIV-1 gp41. Mol Membr Biol. 1999;16(1):11–19. doi: 10.1080/096876899294715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russell R, Paterson RG, Lamb RA. Studies with cross-linking reagents on the oligomeric form of the paramyxovirus fusion protein. Virology. 1994;199(1):160–168. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karron RA, Buonagurio DA, Georgiu AF, Whitehead SS, Adamus JE, Clements-Mann ML, Harris DO, Randolph VB, Udem SA, Murphy BR, Sidhu MS. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) SH and G proteins are not essential for viral replication in vitro: clinical evaluation and molecular characterization of a cold-passaged, attenuated RSV subgroup B mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(25):13961–13966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gonzalez-Reyes L, Ruiz-Arguello MB, Garcia-Barreno B, Calder L, Lopez JA, Albar JP, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Melero JA. Cleavage of the human respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein at two distinct sites is required for activation of membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(17):9859–9864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151098198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zimmer G, Budz L, Herrler G. Proteolytic activation of respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein. Cleavage at two furin consensus sequences. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(34):31642–31650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102633200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]