Abstract

Gene expression profiles of postmortem brain tissue represent important resources for understanding neuropsychiatric illnesses. The impact(s) of quality covariables on the analysis and results of gene expression studies are important questions. This paper addressed critical variables which might affect gene expression in two brain regions. Four broad groups of quality indicators in gene expression profiling studies (clinical, tissue, RNA, and microarray quality) were identified. These quality control indicators were significantly correlated, however one quality variable did not account for the total variance in microarray gene expression. The data showed that agonal factors and low pH correlated with decreased integrity of extracted RNA in two brain regions. These three parameters also modulated the significance of alterations in mitochondrial-related genes. The average F-ratio summaries across all transcripts showed that RNA degradation from the AffyRNAdeg program accounted for higher variation than all other quality factors. Taken together, these findings confirmed prior studies, which indicated that quality parameters including RNA integrity, agonal factors, and pH are related to differences in gene expression profiles in postmortem brain. Individual candidate genes can be evaluated with these quality parameters in posthoc analysis to help strengthen the relevance to psychiatric disorders. We find that clinical, tissue, RNA, and microarray quality are all useful variables for collection and consideration in study design, analysis, and interpretation of gene expression results in human post-mortem studies.

Introduction

It has been a challenge to locate precise candidate genes for complex psychiatric disorders using methods that were successful for simple Mendelian disorders. Complex psychiatric disorders are not caused by one gene, but rather by multiple genes (Mitchell, Mackinnon et al. 1993; Craddock and Jones 1999; Shastry 2005). Complex disorders have been difficult to map for reasons of disease heterogeneity, misclassification and environmental influences. An accurate, yet comprehensive gene expression profile of brain tissue may result in better a understanding of the genotype and phenotype relationships (Nestler EJ 2002; Bunney WE 2003; Mirnics and Pevsner 2004; Altar, Jurata et al. 2005; Erraji-Benchekroun, Underwood et al. 2005; Newton, Bennett et al. 2005).

One highly used technique of gene expression profiling in psychiatric disorders has been microarray studies that use postmortem brain tissue (Barrett, Cheadle et al. 2001; Luo and Geschwind 2001; Mirnics and Pevsner 2004) followed by quantitative real time PCR to confirm candidate genes (Jurata, Bukhman et al. 2004; Mimmack, Brooking et al. 2004). Microarray is a high-throughput method used to screen thousands of genes for alterations in expression between groups. The resulting data has suggested novel pathways linked to psychiatric disorders (Bunney WE 2003; Hosack, Dennis et al. 2003; Mootha, Lepage et al. 2003).

The reliability and reproducibility of microarray results (Auer, Lyianarachchi et al. 2003; Buesa C 2004; Shergill, Shergill et al. 2004) must be constantly evaluated (Konradi, Eaton et al. 2004; Ryan, Huffaker et al. 2004) and is an important question. Previously reports have shown that standard factors such as age, postmortem interval, and medical and family history from proxy respondents increased data reliability (Deep-Soboslay A 2005). It has been reported that the most critical aspect of postmortem research is the integrity of the sample (Mirnics and Pevsner 2004; Tomita, Vawter et al. 2004) and the pH (Li JZ 2004; Mexal, Berger et al. 2006; Vawter, Tomita et al. 2006; Lipska et al., 2006). It has been suggested that samples used for gene expression studies must be of the highest quality (or matched quality) to represent underlying molecular pathophysiology (Dumur CI 2004; Mirnics and Pevsner 2004) and most investigators will attempt to avoid samples with highly degraded RNA. However, inherent in many comorbid psychiatric disorders (e.g. drug overdose and suicide), potential subjects are likely to have varying degrees of quality, and thus elimination of subjects with less than ideal quality would severely restrict research avenues in psychiatric disorders. Therefore, many studies match samples based on several quality parameters. Human postmortem brain tissue profiling has been challenging for several reasons beyond these quality issues (Mirnics K 2001; Mirnics et al., 2006). Polygenic, epigenetic, and environmental factors affect gene profiling (Mirnics K 2001). A presumed narrow range of gene expression in brain tissue due to homeostatic mechanisms restricts the fold-change of differential gene expression observed in microarray analyses of psychiatric disorders (Mirnics and Pevsner 2004). Another complication reported was the dynamic range of gene expression of the transcriptome. For example, in the hippocampus there was about a 2,000 fold difference between highly expressed genes compared to rare transcripts (Evans, Datson et al. 2002). Furthermore, RNA transcription was significantly regulated in the opposite direction to protein (Greenbaum, Colangelo et al. 2003), possibly due to mRNA stability, mRNA turn-over, mRNA steady-state transcription differences, and translation differences. Additionally, pharmacological treatments affected the transcriptome and since most patients with severe psychiatric disorders received medication, while controls do not receive psychiatric drugs, this further complicated interpretation of gene expression results.

In an effort to obtain well-characterized samples, which can be utilized for data analysis, investigators have begun to assess quality parameters thought to be important in postmortem brain tissue studies. One parameter often examined is the clinical quality. One aspect of clinical quality is to obtain correct retrospective psychiatric diagnosis (Deep-Soboslay A 2005). Medical records and next-of-kin interviews were complementary methods for confirmation of the diagnosis of cases and also useful to account for the lack of a psychiatric history in the controls (Brent DA 1993; Kelly TM 1996; Isometsa 2001; Deep-Soboslay A 2005). Another facet of clinical quality is the agonal state of the patient. There is no consensus method for assessing agonal state (Hardy JA 1985; Tomita, Vawter et al. 2004) and thus, the precise effects on microarray quality have yet to be decided (Johnston NL 1998; Buesa C 2004; Iwamoto, Bundo et al. 2005). pH might be a more objective measure of clinical and tissue quality (Johnston NL 1998) because pH was inversely correlated to the agonal state (i.e. the sum of the number of agonal factors as described in Tomita, Vawter et al., 2004) and the duration of agonal state (measured in min, hr, day). In order to assess this correlation correctly of pH and gene expression profiling, the data should be approached with caution, because not all mRNA levels were affected by pH (Barton AJ 1993; Preece and Cairns 2003; Buesa C 2004). For example, about 28% of mitochondrial-related transcripts were affected by pH (Vawter, Tomita et al. 2006). Many researchers have used pH measurements as a substitute for clinical assessments of agonal state and duration (Johnston NL 1998; Preece and Cairns 2003; Buesa C 2004; Mirnics, Levitt et al. 2004). Previous analyses showed that agonal factors were not perfect predictors of microarray and tissue quality and thus, other methods are being developed to assess microarray and sample quality (Li, Meng et al. 2005).

Differences in agonal state are clearly associated with differences in both pH and RNA quality (Harrison PJ 1991; Hynd, Lewohl et al. 2003; Tomita, Vawter et al. 2004). Acidosis in human postmortem brain tissue can be caused by agonal factors such as coma, hypoxia, pyrexia, seizures, dehydration, hypoglycemia, multiple organ failure, head injury, and ingestion of neurotoxic substances, which can affect RNA integrity (Hardy JA 1985; Harrison PJ 1991; Barton AJ 1993; Harrison PJ 1995; Morrison-Bogorad M 1995; Hynd, Lewohl et al. 2003). Along with agonal factors per se, rapidity of death played a role in the outcome of the tissue quality (Harrison PJ 1991; Hynd, Lewohl et al. 2003; Tomita, Vawter et al. 2004). The influence of agonal factors on alterations of neurochemicals in human brain was initially demonstrated by researchers that measured the level of the inhibitory neurotransmitter (GABA) and the biosynthetic enzyme level of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) in schizophrenia and Huntington's chorea (Bird ED 1977; Spokes 1979; Spokes EG 1979; Spokes EG 1980). GABA was decreased in control brains due to hypoxia and long-term illness, but was even more reduced in Huntington's cases (Bird ED 1977; Spokes 1979; Spokes EG 1979; Spokes EG 1980). Hypoxia was a key complication of major agonal events (Buesa C 2004) and it affected gene expression in human postmortem brain (Burke WJ 1991). Hypoxia was reported to ‘cause’ a reduction in pH (Hardy JA 1985; Kingsbury AE 1995; Corbett RJ 1996) possibly by increasing tissue lactate (Hardy JA 1985; Yates CM 1990). A decreased pH was also associated with an increased mitochondrial DNA copy number and an increased number of mitochondrial DNA transcripts in postmortem human brain (Vawter, Tomita et al. 2006). However, lower pH was correlated with long agonal duration, thereby leading to speculation that mtDNA copy number and mtDNA transcription is influenced by pH as well as events occurring in the agonal phase. These results suggest that pH is a useful monitor for agonal events. However, it can not be stated that lower pH will decrease RNA quality due to an effect such as acid hydrolysis within the pH range commonly observed in postmortem brain. Others have reported that a lower pH was associated with compromised RNA integrity (Harrison PJ 1995). Thus, pH and RNA integrity are strongly correlated measures but it cannot be assumed that this represents a ‘cause and effect’ relationship.

Another factor used to assess postmortem samples is tissue quality. Different parameters have been used to assess tissue quality, notably brain pH, gross neuropathological examination, postmortem interval (PMI), and freezer time. Brain pH, as discussed above, has been shown to be related to agonal state and RNA integrity (Harrison PJ 1995; Kingsbury AE 1995; Li JZ 2004; Tomita, Vawter et al. 2004). Postmortem human brain tissue was evaluated using housekeeping gene expression by reverse transcription real-time PCR. The results showed pH was significantly correlated with the gene expression score for 4 housekeeping genes (Miller, Diglisic et al. 2004). Furthermore, when hippocampal gene expression profiles were examined in schizophrenia, pH was found to contribute to a variation in expression that was greater than any other factor evaluated (Mexal, Berger et al. 2006). Additionally, it was reported that pH affected the gene expression of mitochondrial related genes (Li JZ 2004; Iwamoto, Bundo et al. 2005; Vawter, Tomita et al. 2006) and if the effects of pH were not controlled in a posthoc analysis, the gene expression profile results would be a reflection of pH (Li JZ 2004; Mexal, Berger et al. 2006; Vawter, Tomita et al. 2006). It appears that not all mitochondrial related transcripts are affected to the same degree by pH, however large pH effects were seen in non-mitochondrial related gene expression (Vawter et al., 2006).

As a surrogate measure of tissue quality, pH, was reported to be stable in brain tissue after death and during freezer storage (Buesa C 2004). Different regions of the brain may be used for pH measurements, as stable pH measurements in 10 brain regions for 3 subjects were shown (Johnston NL 1998). Cortex has been suggested to be a usable surrogate tissue for pH measurements (Mexal, Berger el al. 2006). The range and average pH measurement of postmortem brain collections varies between brain banks. Part of this variability may be due to the method of pH measurement (Preece and Cairns 2003; Miller, Diglisic et al. 2004; Middleton FA 2005; Torrey EF 2005). Although, a more likely explanation is that this variation is due to the observation that agonal factors are variably related to pH, as discussed above.

Human studies have not shown a clear relationship between PMI and RNA quality (Harrison PJ 1995; Cummings TJ 2001; Catts, Catts et al. 2005). On the other hand, animal studies, which are more carefully controlled, have shown that an increase in the length of the PMI decreased total RNA amounts (Taylor GR 1986). A recent study of murine samples reported that increased PMI was associated with decreased pH and decreased RNA integrity measured by 28S / 18S ratio (Catts, Catts et al. 2005). The acceptable maximum PMI for human studies was reported as 36 - 48 hours (Johnson, Morgan et al. 1986; Barton AJ 1993; Soverchia, Ubaldi et al. 2005). Furthermore, brain refrigeration following death will ultimately slow autolysis and maintain pH homeostasis (Buesa C 2004).

Tissue freezer storage time following autopsy was shown to cause degradation of the poly(A) tail region of RNA (Johnston NL 1998). The loss of the poly(A) tail was thought to result in loss of the rest of the message (Bernstein P 1989), as this caused an exonuclease involved in RNA degradation to assemble (Ford, Bagga et al. 1997; Yang, van Nimwegen et al. 2003; Wilusz and Wilusz 2004). Another concern, was that loss of the poly(A) tail can impede the priming of the oligo-dT in the cDNA synthesis step of the microarray protocol. Furthermore, while the RNases involved in degradation may not be active at low temperatures, when a sample is subjected to freeze-thaw cycles it may result in degradation (Johnston NL 1998).

A third aspect of sample assessment for gene expression profiling is the RNA quality, which is critical for subsequent microarray analysis (Dumur CI 2004). Various criteria have been used to evaluate the integrity of RNA (Buesa C 2004; Dumur CI 2004; Miller, Diglisic et al. 2004). The total RNA ratio, as determined by the Agilent Bioanalyzer, measures the fraction of the area in the 18S and 28S regions. These areas are compared to the total area under the curve and the result is the ratio of large molecules to small molecules. This reading is not sufficient to serve as a universal integrity number. It is now suggested that this reading is better when accompanied with the RNAA Integrity Number (RIN) algorithm. The RIN algorithm does not use the ratio of the ribosomal bands to determine integrity rather; it uses the entire electrophoretic trace. This tool allows for a robust and reliable prediction of RNA integrity (Schroeder, Mueller et al. 2006). Another reported advantage of the Agilent Bioanalyzer was reliability and efficiency compared to standard agarose gel (Grissom, Lobenhofer et al. 2005).

Additionally, cRNA synthesized by in vitro transcription can be assessed as a measure of RNA quality by observing the median length on the Agilent Bioanalyzer (Dumur CI 2004; Ryan, Huffaker et al. 2004) and by spectrophotometer to gauge the A260/A280 absorbance measurements. The synthesis of high quality cDNA and cRNA were associated with the quality of the initial total RNA (Dumur CI 2004; Carter, Robinson et al. 2005).

The stability of human postmortem brain tissue mRNA for use in microarray analyses and real time PCR was shown to be an essential prerequisite for further downstream molecular analysis (Bahn, Augood et al. 2001; Lipska et al., 2006). For example, when RNA was manually degraded, it was shown that 75% of the differential gene expression was actually due to RNA integrity differences between the samples (Auer, Lyianarachchi et al. 2003). Furthermore, the gene expression patterns showed that RNA degradation led to both up and down regulated genes (Auer, Lyianarachchi et al. 2003; Lee, Hever et al. 2005). This was demonstrated by examining degraded total RNA samples at different time points and comparing the results to non-degraded RNA. At each time point, there were a significant number of genes that showed increased expression in the degraded samples when compared to the non-degraded RNA samples. One explanation for this is that RNA fragmentation may have caused a more efficient synthesis of cDNA. However, the RNases active during the freeze-thaw cycles are unpredictable and consequently lead to varying degrees of degradation (Grissom, Lobenhofer et al. 2005).

RNA degradation can be complex due to the structure of RNA (Hollams, Giles et al. 2002) and the sequence of the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) (Berger, Stierkorb et al. 2005). The 3′-UTR sequence may have altered the stability of some RNA transcripts (Berger, Stierkorb et al. 2005) that harbor the AU-rich elements (AREs) and iron-responsive elements (IREs), both of which play a role in destabilizing some RNAs (Hollams, Giles et al. 2002). mRNA degradation occurred from the 3′ end, the 5′ end, or from internal positions (Buesa C 2004). The loss of the 5′ cap led to 5′ → 3′ decay and loss of the poly(A) tail led to 3′ → 5′ decay by exonuclease activity ((Buesa C 2004). Fritz, Bergman et al. 2004; Wilusz and Wilusz 2004), but the predominant degradation pathway in mammals was not determined (Yang, van Nimwegen et al. 2003; Wilusz and Wilusz 2004). It has been observed that low degradation caused a reduction in transcript length, but did not reduce the total amount of transcripts (Ryan, Huffaker et al. 2004). However, when genes were organized by functional classes the variation of decay rates between classes of mRNAs was significantly different (Yang, van Nimwegen et al. 2003).

Affymetrix gene expression probes on the U133 series of chips were designed toward the 3′ end and also further toward the 5′ end of several housekeeping genes (GAPDH and ACTB). The ratio of 3′ / 5′ expression was evaluated as a measure of transcript degradation. Although, because the site of degradation is unknown, in theory, it is possible to have a low 3′/ 5′ ratio (meaning relatively intact RNA) in a slightly degraded sample (Dumur CI 2004; Ryan, Huffaker et al. 2004). Several studies have reported that slight RNA degradation does not have a substantial effect on the number of genes detected in the “Present Call” reading on the Affymetrix arrays (Schoor O 2003; Ryan, Huffaker et al. 2004; Lee, Hever et al. 2005). These studies examined only a small subset of the probesets on the arrays due to the restrictions in the design of each experiment (Schoor O 2003; Lee, Hever et al. 2005) and furthermore, it was shown that for each transcript the exact mechanism of RNA degradation was unclear (Ryan, Huffaker et al. 2004).

An often-overlooked aspect of discussions of degradation of mRNA is that frequently a spurious increased expression was found using microarray technology (Bahn, Augood et al. 2001; Auer, Lyianarachchi et al. 2003; Schoor O 2003; Buesa C 2004; Ryan, Huffaker et al. 2004; Lee, Hever et al. 2005). RNA degradation was induced by an in vitro perturbation experiment and a list of 31 genes was found to be significantly different due to RNA degradation alone (Auer et al., 2003). Our group recently published a list of genes found to be affected by pH in 3 brain regions (Vawter, Tomita et al. 2006). The complete Excel table can be downloaded here: http://pritzkerneuropsych.org/data/archive/File022206.aspx. We considered agonal-pH sensitive genes in a control group analysis only, and found 570 genes that were dysregulated across two or more brain regions (DLPFC, ACC, or CB) meeting a fold change criteria of ± 1.25 and in the top 5% ranked differential gene expression values. This data suggested labile transcripts in postmortem tissue may be used advantageously to indicate degradation and/or an imbalance due to agonal-pH factors. Implementing a protocol to qualitatively assess RNA integrity significantly improved the quality of microarray data (Carter, Robinson et al. 2005).

The final quality parameter in gene expression profiling is the microarray quality. Affymetrix MAS 5.1 software determines whether each transcript was reliably detected using a percent present call (%PC) and a scaling factor (SF), which adjusted the average signal intensity to a preset constant. The %PC and SF obtained from the microarray results were used as gross indicators of RNA degradation or abundance (Ryan, Huffaker et al. 2004; Lee, Hever et al. 2005). When RNA was experimentally degraded the %PC was 40%, and with intact RNA the %PC was 54% (Lee, Hever et al. 2005). Thus, chips with lower present calls in a sample set must be treated with caution during analysis if the differences are significant this could be due to true biological differences or quality covariables. Prior reports have shown that differences in mRNA quality produced significant changes in microarray %PC and SF (Ryan, Huffaker et al. 2004; Lee, Hever et al. 2005).

Agonal factors, pH, and RNA integrity were each related to the post hoc microarray measure called the Average Correlation Index (ACI), which was a chip quality indicator (Tomita, Vawter et al. 2004). Another method for examining microarray similarity involved hierarchical clustering of samples and gene expression results (Li JZ 2004; Iwamoto, Bundo et al. 2005; Mexal, Berger et al. 2006). Hierarchical clustering of samples by pH was independently replicated in a set of 105 DLPFC (Iwamoto, Bundo et al. 2005) and a set of 24 human hippocampal samples (Mexal, Berger et al. 2006). Not surprisingly, the composition of groups based upon pH and agonal factor states was recommended as criteria for matching samples in human postmortem studies of single gene and protein expression, for examples see (Hardy JA 1985; Harrison PJ 1991; Kingsbury AE 1995; Johnston NL 1998; Preece and Cairns 2003).

Postmortem brain tissue is a limited resource and a major effort has been put forth to obtain well characterized subjects. By evaluating the above quality factors in this paper the results will aid in future study design, analysis, and result interpretation. The present study was undertaken to address 4 broad quality indicators for evaluating the quality of postmortem samples for gene expression profiling.

Methods

Quality Control Indicators

Quality control indicators were analyzed for 98 anterior cingulate (ACC) and 91 matched cerebellum (CB) samples with microarray profiling results using U133A and U133P Affymetrix chips. Included in the 98 ACC samples were bipolar disorder (n = 16), schizophrenia (n = 19), control (n =42), and major depression (n = 18) samples. However, diagnostic groupings were not used to assess quality. Clinical quality was assessed by agonal risk and agonal duration that yielded agonal factor scores (AFS). RNA quality was determined based on the 28S / 18S rRNA readings and the RNA integrity number (RIN) both obtained from the Agilent Bioanalyzer. The 3′ / 5′ glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and β-actin (ACTB) housekeeping gene ratios were from the Affymetrix Microarray Suite 5.1 (MAS 5.1) report. Standard denaturing agarose gels were also run for RNA quality, and the AffyRNAdeg software program to compute RNA degradation (see RNA Quality Measurements below). RNA degradation was evaluated using 4 quality indicators in two brain regions. Tissue quality was assessed by pH measurement, post mortem interval (PMI) and freezer time variables. Microarray chip quality was evaluated using the percent present call, scaling factor, average correlation index (ACI) of the chip (Tomita, Vawter et al. 2004), and by gene clustering after array processing (Type 1 / Type 2) (Li JZ 2004; Iwamoto, Bundo et al. 2005; Mexal, Berger et al. 2006).

Agonal Factor Score (AFS)

We calculated the AFS based on data collected for each subject, which included the patient's physical health, medication use, psychopathology, substance abuse and details of death. This information was obtained from the medical examiner's conclusions, coroner's investigation, medical records and family interviews. Agonal risk and agonal duration scores were summed to give the final AFS for each subject as described in a prior study (Tomita, Vawter et al. 2004).

pH Measurements

Brain pH measurements were taken using a 50-100 mg piece of frozen cerebellar cortical slice. The frozen tissue was mixed with 1.0 mm glass beads (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK) and distilled deionized water to form a 10% (w/v) solution. This solution was homogenized by shaking with a Bead-Beater (Biospec Products) for 60 sec at 4°C. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 2 min at 4°C and then equilibrated to room temperature for 10 sec and the pH was measured. The pH meter (Corning, Cypress, CA) was calibrated with 3 standard buffer solutions (pH 4, 7, and 10). The pH was measured in a second laboratory by the same the technique on the same samples and the results were highly concordant between the laboratories (r = 0.97, n =10). This was also repeated in a third laboratory (r = 0.99, n = 7). To use a tissue for a single point calibration of our pH measurement technique, we subjected postmortem non-human primate brain cerebella to the same measurement pH method and found the average pH was 7.24 ± 0.15 (n = 6). This non-human primate experiment had an absence of agonal factors and had a short PMI, which may explain why a higher average pH was found, compared to postmortem human brain collections.

RNA Quality Measurements

1). Total RNA was extracted from ACC (n = 98) and CB (n = 91) and evaluated on Agilent Technologies 2100 BioAnalyzer (Palo Alto, CA) to obtain the 28S / 18S ratio. 2). The RNA integrity number (RIN) was determined using Agilent Technologies 2100 Expert Software. The RIN is a software tool used to aid in the estimation of RNA integrity and to compare RNA integrity across samples (Imbeaud S 2005). This tool reads the entire electropherogram rather that just the 28S / 18S ribosomal bands. The RIN reflected the presence and absence of degradation products; where higher RNA degradation was assigned a lower RIN value.

3). A measure of RNA integrity was acquired via the microarray gene chip analysis based on the 3′/5′ ratio of signal intensities of the probe sets for the housekeeping genes glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and β-actin (ACTB) derived from Affymetrix MAS 5.1 signal intensity.

4). A post hoc microarray measure of RNA degradation was proposed which utilized the R program function AffyRNAdeg (R program, Function to assess RNA degradation in Affymetrix GeneChip data) (Cope 2005). This measurement was based on the fact that Affymetrix arrays have individual probes tiled in a 3′ to 5′ direction along the transcript, therefore an algorithm was created to measure the decay of transcript abundance, i.e. the signal decline within each gene on the Affymetrix GeneChip. The calculations were executed based on the assumption that primer transcription starts at the 3′ end and therefore, probe intensities should be lower at the 5′ end of a probeset compared to the 3′ end if RNA is degraded. This program calculates the average probe intensity based on location in the probeset and produces a plot of the means for each chip by probe. The slope of this graph was used as a measure of the severity of degradation (Gautier 2005).

5). Total RNA samples were run on a denaturing agarose gel according to a protocol from Ambion (Austin, TX). The agarose gel was quantitated on the BioRad ChemiDoc System and the 28S / 18S ratio was determined. The Agilent 28S / 18S readings were compared with the results of the same set of samples run on the agarose gel by a paired t-test.

Microarray chip quality

In the current sample, differential gene expression was determined using GC content robust multi-array average (gcRMA) (Wu 2003). We applied a Unigene 4 custom chip definition file (Dai, Wang et al. 2005), which is available at: http://brainarray.mbni.med.umich.edu/Brainarray/Database/CustomCDF/CDF_download_v4.asp. RMA was used to process the cel files for signal intensity and the signal intensity was used for gene clustering (Type 1 / Type 2) after array processing (Li JZ 2004; Iwamoto, Bundo et al. 2005; Mexal, Berger et al. 2006). The percent present call, the scaling factor and the average correlation index (ACI) of the chip were determined using MAS 5 generated values (Tomita, Vawter et al. 2004). Pathway enrichment of differential gene expression was examined by GSEA (gene set enrichment analysis) (Mootha, Lindgren et al. 2003).

The relationship of the quality parameters to the total variance was estimated by two methods. The receiver operator characteristic plots of sensitivity and specificity were used to determine the inter-relationships of the quality covariables in determining microarray outcome. This was determined quantitatively by measuring the area under the ROC curve and comparing different quality variables. However, this provided an assessment related to microarray outcomes, so a direct approach was to look at the total variation accounted for by each quality covariable across all genes in ANCOVA analyses. The F-ratios for each covariate was averaged across all probesets on the Affymetrix U133A platform.

Results

Clinical Quality

The current sample consisted of anterior cingulate ACC (n = 98) and matched cerebellum CB (n = 91) samples, i.e. 91 subjects had data for two brain regions (Table 1). Cases were included in the present data in which both medical records and next-of-kin interviews were obtained (Table 1). The controls were also ascertained with the same method so a similar level of rigor was applied to the controls. We did not assess case-control differences but assessed all samples together to minimize analyses, and to maintain power with a large number of subjects. The subjects were diagnosed as bipolar disorder (16%), major depression (18%), schizophrenia (20%) or controls (46%).

Table 1. Summary of quality control indicators for ACC and CB.

Summary of four quality control measures for brain samples from anterior cingulate (n = 98) and cerebellum (n =91). The categories of the 4 quality control indicators are displayed for each brain region. There were 91 common

| Clinical | Tissue | RNA | Microarray Chip | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Region | Age | 1AFS 0 / AFS> 0 | pH | PMI (hrs) |

Freeze Time (yrs) |

28S / 18S ratio | 3′ / 5′ GAPDH2 |

3′ / 5′ ACTB3 |

RIN4 | % PC5 | SF6 | ACI7 | Type 1 /28 |

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) (N = 98) | 51.98 (13.40) | 75 / 23 | 6.82 (0.24) | 24.14 (8.63) | 2.96 (3.34) | 1.80 (0.37) | 1.68 (0.70) | 2.93 (1.80) | 5.95 (1.35) | 43.02 (5.22) | 1.42 (1.57) | 0.94 (0.06) | 71 / 27 |

| Cerebellum (N = 91) | 51.64 (13.20) | 75 / 16 | 6.83 (0.24) | 23.72 (8.41) | 3.15 (3.40) | 1.89 (0.46) | 1.70 (0.77) | 3.55 (3.03) | 6.58 (1.66) | 43.94 (5.48) | 2.57 (4.16) | 0.96 (0.05) | 64 / 27 |

AFS = agonal factor score, number refers to the number of subjects with AFS = 0 / AFS > 0

GAPDH = glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase

ACTB = β-actin

RIN = RNA integrity number

%PC = percent present call

SF = scaling factor

ACI = average correlation index

Type 1 / 2 = Hierarchical Clustering group membership which is defined by cluster membership.

We established two groups of subjects based upon agonal factor scores (AFS = 0 versus AFS > 0) and compared these groups for differences in tissue, RNA, and microarray quality. The 3 categories of quality indicators (tissue pH, RNA quality, and microarray quality) were significantly different between AFS = 0 and AFS > 0 samples for both brain regions (Fig 1, Table 2).

Figure 1.

The significance of comparing groups separated by differences in high vs low RNA quality, clinical quality, and tissue quality is shown for multiple variables commonly used in controlling gene expression profiling experiments and in particular microarray results (%PC, SF, ACI, and Type 1 / 2). The data is from Table 2 for the anterior cingulate cortex and shows on the y-axis the significance of t-test (p value transformed by −log10) and the x-axis shows the individual variables. The abbreviations are same as shown in Table 1. The legend shows three different groups (AFS, pH, and RNA).

Table 2. Quality Control Assessment.

Quality control assessment. Each quality control measure is based on the criteria listed below for both anterior cingulate (ACC) and cerebellum (CB). The averages (± standard deviation) are shown for each criterion and significant differences between the groups were determined by t-test. The resulting significant p-values are shown in bold. The abbreviations are the same as used in Table 1. N/A indicates that due to a priori selection of quality by AFS, pH, and RNA these produced highly significant differences therefore the p-value was not shown.

| Clinical Quality | Tissue Quality | RNA Quality | Microarray Chip Quality | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Brain | Criteria | Age | AFS*

0 / ≥1 |

pH | PMI (hours) |

Freezer Time (years) |

28S/18S | 3′ / 5′ GAPDH | 3′ / 5′ ACTB | RIN | % PC | SF | ACI | Type 1/2* 1 / 2 |

| ACC | AFS = 0 (n = 75) | 50.49 (13.87) | N/A | 6.87 (0.20) | 25.04 (8.48) | 2.85 (3.08) | 1.86 (0.36) | 1.68 (0.72) | 3.02 (1.97) | 6.05 (1.08) | 43.19 (4.87) | 1.06 (0.93) | 0.95 (0.04) | 61 / 14 |

| AFS ≥ 1 (n = 23) | 56.83 (10.57) | N/A | 6.69 (0.31) | 21.22 (8.67) | 3.33 (4.15) | 1.60 (0.31) | 1.66 (0.64) | 2.62 (1.06) | 5.73 (1.81) | 42.45 (6.33) | 2.58 (2.48) | 0.90 (0.08) | 10 / 13 | |

| p-value | 0.02 | N/A | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.61 | 0.001 | 0.90 | 0.21 | 0.44 | 0.61 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.0009 | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| CB | AFS = 0 (n = 75) | 50.49 (13.87) | N/A | 6.87 (0.20) | 24.27 (8.28) | 2.85 (3.08) | 1.96 (0.45) | 1.62 (0.77) | 3.62 (3.28) | 6.58 (1.66) | 45.18 (3.89) | 1.37 (2.10) | 0.97 (0.04) | 61 / 14 |

| AFS ≥ 1 (n = 16) | 57.06 (7.65) | N/A | 6.64 (0.33) | 21.16 (8.80) | 4.53 (4.48) | 1.56 (0.39) | 1.97 (0.71) | 3.24 (1.35) | 4.99 (1.64) | 38.09 (7.83) | 7.01 (5.95) | 0.90 (0.07) | 3 / 13 | |

| p-value | 0.01 | N/A | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.00125 | 0.09 | 0.45 | 0.0001 | 0.0025 | 0.0017 | 0.01 | <0.000005 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| ACC | pH ≥ 6.6 (n = 81) | 51.23 (13.67) | 67 / 14 | N/A | 23.89 (8.22) | 2.97 (3.26) | 1.75 (0.37) | 1.52 (0.53) | 2.55 (1.40) | 6.09 (1.25 ) | 44.13 (4.26) | 1.19 (1.20) | 0.96 (0.03) | 69 / 12 |

| pH < 6.6 (n = 17) | 55.53 (11.71) | 9 / 8 | N/A | 25.35 (10.60) | 2.96 (3.82) | 1.49 (0.41) | 2.46 (0.88) | 4.70 (2.40) | 5.34 (1.56) | 37.71 (6.20) | 2.46 (2.54) | 0.91 (0.06) | 2 / 15 | |

| p-value | 0.19 | 0.02 | N/A | 0.60 | 1.00 | 0.00017 | 0.0005 | 0.0022 | 0.12 | 0.0006 | 0.06 | 0.01 | <0.000005 | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| CB | pH ≥ 6.6 (n = 74) | 50.76 (13.44) | 66 / 8 | N/A | 23.81 (8.42) | 3.19 (3.32) | 1.92 (0.43) | 1.58 (0.72) | 3.34 (3.06) | 6.73 (1.66) | 44.81 (4.65) | 2.03 (3.41) | 0.97 (0.03) | 62 / 12 |

| pH < 6.6 (n = 17) | 55.53 (11.71) | 9 / 8 | N/A | 23.37 (8.64) | 2.96 (3.82) | 1.73 (0.56) | 2.11 (0.84) | 4.49 (2.81) | 6.03 (2.13) | 40.14 (7.18) | 3.80 (4.92) | 0.91 (0.09) | 2 / 15 | |

| p-value | 0.15 | 0.002 | N/A | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.02 | <0.000005 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| ACC | 28S/18S ≥1.5 (n = 73) | 49.84 (13.62) | 64 / 14 | 6.86 (0.22) | 23.99 (7.92) | 2.83 (3.31) | N/A | 1.55 (0.57) | 2.73 (1.78) | 6.08 (1.35) | 43.57 (5.10) | 1.29 (1.53) | 0.96 (0.03) | 60 / 13 |

| 28S/18S < 1.5 (n = 25) | 58.24 (10.67) | 11 / 9 | 6.72 (0.27) | 24.59 (10.62) | 3.35 (3.48) | N/A | 2.07 (0.89) | 3.48 (1.78) | 5.56 (1.45) | 41.42 (5.35) | 1.76 (1.69) | 0.93 (0.05) | 11 / 14 | |

| p-value | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00002 | 0.51 | 0.93 | N/A | 0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.11 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.00003 | 0.0005 | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| CB | 28S/18S ≥1.5 (n = 76) | 51.33 (13.50) | 66 / 10 | 6.86 (0.24) | 24.17 (8.10) | 3.03 (3.28) | N/A | 1.50 (0.54) | 3.06 (2.53) | 6.91 (1.45) | 45.00 (4.55) | 1.80 (2.89) | 0.97 (0.03) | 60 / 16 |

| 28S/18S < 1.5 (n = 15) | 53.27 (11.84) | 9 / 6 | 6.63 (0.19) | 21.49 (9.87) | 3.72 (4.04) | N/A | 2.58 (1.10) | 6.07 (4.06) | 4.49 (1.44) | 38.53 (6.69) | 5.20 (6.02) | 0.91 (0.08) | 4 / 11 | |

| p-value | 0.58 | 0.02 | 0.0002 | 0.34 | 0.55 | N/A | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.0006 | 0.002 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.0001 | |

p-values for AFS and Type 1 / 2 were calculated using Fisher's exact test.

An over-representation analysis revealed that the mitochondrial pathway of gene expression was affected by AFS. Analysis of ACC showed that mitochondrial enzymes were significantly over-represented when comparing AFS = 0 and AFS > 0 (Table 3). Agonal duration and pH were significantly correlated (r = −0.43, p < 0.0001). These results (n = 98) agreed with our previously published data which included 40 subjects (Vawter, Tomita et al. 2006).

Table 3. Differential expression of genes in the mitochondrial pathway.

Differential expression of genes in the mitochondrial pathway. Differential gene expression was determined in two brain regions and used for ranking in an over-representation analysis (GSEA gene set enrichment analysis, (Mootha, et al., 2003). The over-representation analysis used subject permutation to correct p-values for multiple test comparisons.

| Brain Region | Pathway Search | Pathway | Subjects with AFS = 0 Compared to Subjects with AFS > 0 | Subjects with pH ≥ 6.6 Compared to Subjects with pH < 6.6 | Subjects with 28S / 18S ≥ 1.5 Compared to Subjects With 28S / 18S < 1.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC | KEGG | Oxidative Phosphorylation | 4.85E-02 | NS* | 1.00E-02 |

| Gene Ontology | Mitochondria | NS | 4.30E-02 | 1.30E-02 | |

| CB | KEGG | Oxidative Phosphorylation | 4.00E-03 | 2.70E-02 | NS |

| Gene Ontology | Mitochondria | 4.30E-02 | 6.50E-03 | NS |

NS = not significant

Tissue Quality For Gene Expression Profiling

Some brain banks have collected brains ∼10-30 years older than the current sample (Breese, Marks et al. 1997; Hakak, Walker et al. 2001; Konradi, Eaton et al. 2004). Because of the high average age of these cases, investigators routinely utilized microscopic neuropathological examinations to rule out age-related neurodegeneration in cases and controls. In the present study, subjects were relatively young at the time of death (Table 1) and were excluded if they showed clinical signs of dementia prior to death. Therefore a neuroanatomist performed gross neuropathological examinations of all subjects after the brain had been sliced into 1 cm coronal slabs to rule out hemorrhage, gross infarcts, and lesions. Any subjects with gross neuropathology were excluded.

The pH and AFS measures were significantly correlated (r = −0.44, p < 0.01, df = 89) therefore the residual variation between pH and AFS must be accounted for by other unmeasured variables. We found that subjects with zero agonal factors, which included only short agonal duration of minutes and no prolonged illnesses had a range of pH from 6.3 – 7.26 (Fig 2). The average pH was 6.83 (n = 98) and the median was 6.87 (Fig 2).

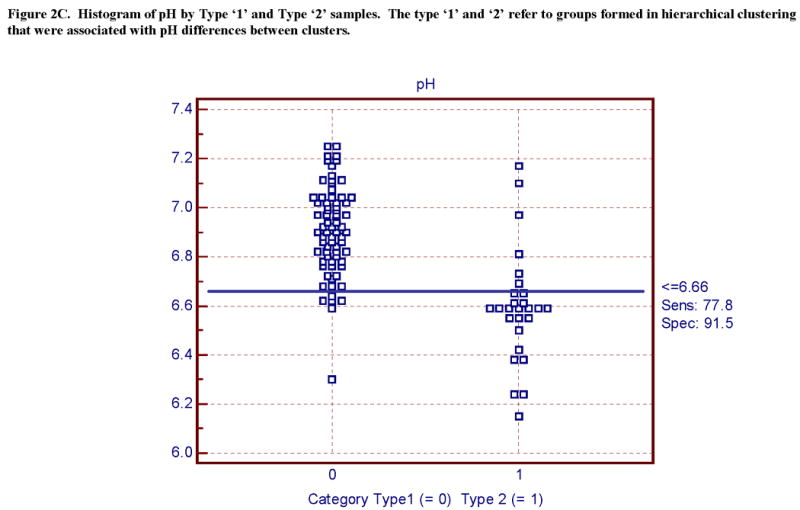

Figure 2.

(A) Sensitivity of pH and (B) RNA to AFS 0 and AFS > 0. The majority of 98 cases show a pH above an arbitrary cut point of 6.73 and RNA quality above a cut-point of 1.4, however there are outliers within AFS = 0 and AFS 1 categories. The combined use of three quality measures of pH, RNA, and AFS results in less differences in gene expression as a result of agonal-pH effects (Vawter et al., 2006). (C). Type ‘1’ and ‘2’ microarray outcome strongly depends on pH (Li et al, 2004).

Figure 2A. Histogram of pH by AFS.

Figure 2B. Histogram of RNA quality (28S/18S) by AFS.

Figure 2C. Histogram of pH by Type ‘1’ and Type ‘2’ samples. The type ‘1’ and ‘2’ refer to groups formed in hierarchical clustering that were associated with pH differences between clusters.

In order to assess the statistical relationships of pH on RNA integrity and microarray quality, the subjects were arbitrarily divided into high pH (≥ 6.6) and low pH (< 6.6). In a statistical sense, pH significantly affected measures of RNA quality and microarray quality for both brain regions by t-test comparisons of the high and low pH groups (Fig 1, Table 2).

The PMI was not statistically associated with pH or RNA integrity (Fig 1, Table 2). This was not surprising because the average PMI was 24.1 ± 8.6 hours and during the collection process any sample with a PMI over 48 hours would not be collected. Furthermore, a majority of the postmortem cases received from the coroner's office were placed in the refrigerator within hours after death pending autopsy. The average ± standard deviation of the postmortem time to refrigeration was 6.5 ± 4.2 hours. The average freezer time ± standard deviation for the 98 ACC samples was 2.9 ± 3.3 years and there were no significant relationships between freezer time and RNA quality (Table 2, Table 4). However, an in vitro perturbation of RNA to assess one freeze-thaw cycle that could occur during prolonged freezer storage conditions of small RNA aliquots modestly increased RNA degradation (next section).

Table 4. Genes in common with Auer et al.

The top 5% of dysregulated genes in ACC comparing different groups based on AFS, pH and 28S/18S were compared to genes listed in Auer et al. (2003) that were found to be dysregulated due to RNA degradation. There were 31 genes listed in Auer et al. (2003) changed by RNA degradation.

| GENE SYMBOL | Auer et al. Up/Down | AFS=0 VS AFS=+1 | pH ≥ 6.6 VS pH < 6.6 | 28S/18S ≥ 1.5 VS 28S/18S < 1.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNAS | Down | X | X | |

| CHD1 | Down | X | ||

| GDI2 | Down | X | ||

| ATP5A1 | Down | X | X | |

| YWHAZ | Down | X | X | |

| PCBP1 | Down | X | X | |

| TEGT | Down | X | ||

| B2M | Down | X | X | |

| NME1 | Up | X | X | |

| ATP5B | Up | X | X |

Comparisons of the top 5% of dysregulated genes between our ACC samples revealed 194 genes in common between AFS and pH, 202 genes in common between AFS and 28S/18S and 417 genes in common between pH and 28S/18S. There were 146 genes in common between the three groups.

The mitochondrial gene pathways were significantly different between the groups with high pH (≥ 6.6) and low pH (< 6.6) using an over-representation analysis of GO terms for cellular, biological, and molecular components (Vawter, Tomita et al. 2006). The mitochondrial pathway was significantly over-represented between the high pH and low pH groups for the KEGG analysis and the GO mitochondrion cellular component term (Table 3). These results were similar to the comparisons of the AFS groups (see clinical quality section above), as pH and the AFS (sum of the number of agonal factors) were significantly correlated (r = −0.44, p < 0.01, Fig 2).

RNA Quality

We induced RNA degradation in vitro by freeze-thawing RNA extracts from brain to simulate what might be observed during prolonged freezer storage, as aliquots in small volumes may freeze-thaw on occasion especially when moving samples in and out of the freezer. RNA samples that were fresh frozen, thawed once at room temperature and then subjected to an additional freeze-thaw cycle showed no differences in the integrity of total RNA determined by quantification of 28S / 18S ribosomal RNA ratios on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. However, the Agilent RNA integrity number (RIN) showed significantly more degradation in the twice thawed samples compared to the thawed once samples (p = 0.0018). These results support the ability of the RIN algorithm to robustly detect mild degradation differences between samples compared to the 28S/18S ratio which did not detect any difference.

Total RNA 28S / 18S ratios from a set of samples were measured on both the Agilent Bioanalyzer and on a denaturing agarose gel. The paired t-test between the methods was significant (p = 0.03) and the Agilent 28S / 18S readings were consistently higher than the agarose gel 28S / 18S ratio, as previously observed (Boris Sokolov, personal communication). Thus, setting a low threshold for Agilent quality translated to a lower quality measurement by conventional formaldehyde gel electrophoresis.

To measure the effect of RNA degradation on other quality parameters, the samples were divided into high (≥ 1.5) and low (< 1.5) 28S / 18S total RNA based upon Agilent measures. The median length of cRNA was significantly decreased in the low 28S / 18S group (p = 0.03) compared to the high 28S / 18S group confirming that shorter transcripts, as shown by cRNA length, are indeed made from degraded total RNA. Additionally, the samples with pH < 6.6 displayed a shorter size of the cRNA in vitro transcript compared to the higher pH group> 6.6 (p = 0.006). A poor quality total RNA was associated with shorter cRNA transcripts.

We found significant correlations between the 28S / 18S ratio and 3′ / 5′ GAPDH ratio (r = −0.64, p < 0.01, df = 89) and between the 28S / 18S and 3′ / 5′ ACTB (r = −0.48, p < 0.01, df = 89). As expected, the negative correlations indicated higher 3′ / 5′ signal ratios, which was associated with poorer starting RNA quality. GAPDH 3′ / 5′ ratio presents a view of short transcript degradation while the ACTB 3′ / 5′ ratio gives a view of longer transcript degradation in postmortem brain. Hence, this was the reason that samples often showed a large disparity between the two ratios.

We employed an arbitrary criterion for 28S / 18S Agilent measure (≥ 1.5) which produced a significant difference in the 4 quality measures in ACC and in CB (Fig 2, Table 2). There was a technical problem in measuring the RIN in the ACC, so not all samples were measured. The technical issue might have biased our measures towards a lower RIN value for ACC compared to the CB samples leading to this regional variability. However, the 28S / 18S measure was very robust and the mitochondrial pathway was significantly different between the 28S / 18S groups in both the KEGG pathway and GO terms for cellular component in ACC. The significance was also observed in CB for the KEGG pathway (Table 3).

Another question we addressed was if a consistent set of labile genes in degraded samples existed which could be used to survey the degradation and adjust for degradation effects using the labile gene set. The top 5% of genes dysregulated by the AFS, pH, and 28S / 18S comparisons were matched to the Auer et al. (2003) gene list. There were 9 genes in common between the 31 genes found by Auer et al. (2003) and the present study indicating that certain labile transcripts are dysregulated when the postmortem brain sample was degraded (Table 4). Furthermore, in the present study there were 146 altered genes in common between all three group comparisons of AFS, pH, and 28S / 18S.

Microarray Chip Quality

The results presented thus far, have largely focused on the impacts and inter-relatedness of clinical, tissue, and RNA quality. We have also examined pathway analysis for mitochondrial related transcripts, and will later address the issue of variability of the quality factors across the entire transcriptome. It can be summarized that using only one quality indicator did not account for the total picture of sample variability and selection because each quality indicator was partially and not perfectly correlated (see Table 5 for correlation matrix of quality indicators, Figure 2).

Table 5. Correlation of quality control measures.

Correlations of quality control measures. Each quality control measure is organized by the 4 categories (clinical, tissue, RNA, microarray) and then correlated for cerebellum data. The significant correlations are in bold (p < 0.01). Abbreviations are the same as in Table 1.

| Clinical Quality | Tissue Quality | RNA Quality | Microarray Quality | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | AFS | pH | PMI | Freezer time | 28S / 18S | 3′ / 5′ GAPDH | 3′ / 5′ ACTB | RIN | cRNA (∼nts) | PC | SF | ACI | Type 1/2 | |

| Age | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| AFS | 0.19 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| pH | −0.20 | −0.44 * | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| PMI | −0.05 | −0.13 | 0.12 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Freezer time | −0.19 | 0.17 | 0.00 | −0.44 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 28S/18S | −0.04 | −0.25 | 0.33 | 0.11 | −0.18 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 3′/5′ GAPDH | 0.08 | 0.21 | −0.35 | 0.13 | −0.01 | −0.64 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 3′/5′ ACTB | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.20 | 0.21 | −0.18 | −0.48 | 0.86 | 1.00 | ||||||

| RIN | −0.02 | −0.52 | 0.31 | 0.25 | −0.37 | 0.68 | −0.63 | −0.37 | 1.00 | |||||

| cRNA (∼nts) | −0.15 | −0.21 | 0.22 | −0.19 | 0.34 | 0.14 | −0.42 | −0.34 | 0.28 | 1.00 | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| PC | −0.04 | −0.46 | 0.38 | 0.17 | −0.40 | 0.53 | −0.47 | −0.17 | 0.63 | 0.21 | 1.00 | |||

| SF | 0.01 | 0.52 | −0.25 | −0.34 | 0.45 | −0.41 | 0.27 | 0.02 | −0.70 | −0.22 | −0.82 | 1.00 | ||

| ACI | −0.06 | −0.53 | 0.46 | −0.03 | −0.10 | 0.58 | −0.70 | −0.49 | 0.63 | 0.39 | 0.65 | −0.41 | 1.00 | |

| Type 1 / 2 | 0.17 | 0.49 | −0.61 | 0.16 | 0.01 | −0.42 | 0.47 | 0.24 | −0.34 | −0.33 | −0.48 | 0.30 | −0.59 | 1.00 |

Bold correlations were significant (r > |0.267|, p < 0.01, df = 89).

After the samples were completely processed the data from the microarray chip provided a set of indicators to measure overall chip quality and derivative measures of RNA degradation. The Affymetrix MAS 5.1 software was used to determine whether each transcript was reliably detected using a percent present call (%PC) and a scaling factor (SF), which adjusted the average signal intensity to a preset constant. Microarray chip quality was evaluated in the present study at cut points for the other three quality measures (AFS = 0, pH ≥ 6.6 and 28S / 18S ≥ 1.5). Two microarray quality indicators, %PC and SF, were significantly different in both ACC and CB for RNA quality and for pH (tissue quality) group comparisons (Fig 2, Table 2). Thus, differences in mRNA quality were related to significant changes in microarray %PC and SF.

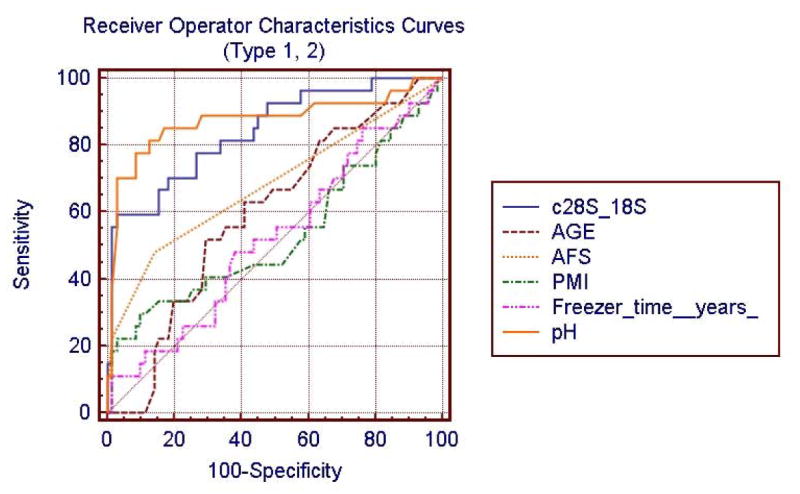

ACI was significantly different between all three groups (AFS, pH, and 28S / 18S shown in Fig 2 and Table 2) for both brain regions. Employing these same cut points for AFS, pH and 28S / 18S revealed significant differences (p values ranged from 9.6E-09 - 5.2E-04) between the ‘Type 1’ and ‘Type 2’ groups for the current samples (Table 2, Figure 2). The ROC plots and data table showed similar findings that pH and RNA quality were equally related to ‘Type 1’ and ‘Type 2’ membership (illustrated in Fig 2-3, and Table 6).

Figure 3.

The diagnostic performance of test variables, or the ability of a variable to discriminate microarray outcome (Type ‘1’ vs Type ‘2’) is evaluated using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The ROC curves are shown for 6 quality variables that relate differentially to microarray outcome. The area under each curve shows a relationship to overall prediction of Type ‘1’ and ‘2’ microarray outcome. The comparison of ROC curves for tissue quality (pH, freezer time, PMI), clinical quality (AFS, age), or RNA quality (28S / 18S) shows that tissue quality pH measure is strongly related to Type 1 and Type 2 microarray outcome (Li et al., 2004). Table 6 shows the ROC values for each variable.

Table 6. ROC values.

The comparison of receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves for microarray Type 1 or Type 2 outcome (Li et al., 2004). Tissue quality (pH) and RNA quality (28S / 18S) strongly associated with accurate detection of Type 1 and Type 2 microarray outcome. The ROC plot for these variables is shown in Fig 3.

| Quality Variable | Area Under ROC (maximum area = 1) | Standard Error | 95% C.I. |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 0.874 | 0.035 | 0.792 − 0.933 |

| 28S / 18S RNA ratio | 0.841 | 0.040 | 0.754 − 0.907 |

| * AFS | 0.683 | 0.063 | 0.581 −0.773 |

| * Age | 0.597 | 0.066 | 0.493 − 0.694 |

| * Freezer Time | 0.523 | 0.066 | 0.420 − 0.625 |

| * PMI | 0.532 | 0.066 | 0.429 − 0.634 |

The area under the ROC column was significantly increased for RNA quality and pH compared to all other variables except the pH.

We tested more global gene expression parameters in two further methods. First, the AffyRNAdeg function modeled the extent of RNA degradation and thus could possibly control for this effect across samples at the probe level. The slope generated by AffyRNAdeg, which putatively measured the severity of degradation, was found to be significantly correlated with %PC (r = −0.36, p = 0.0005), 3′/5′ GAPDH (r = 0.47, p < 0.0001), 3′/5′ ACTB (r = 0.76, p < 0.0001), and cRNA length (r = −0.35, p = 0.0007). The AffyRNAdeg slope variable was used as a covariate in PLMfit (Bolstad 2004) and this reduced the residual variation between duplicate RNA samples run on chips at different laboratories (data not shown).

The second method of testing global gene expression relationships to the 4 groups of quality covariables was to enter each variable as either a main effect if categorical such as AFS or ‘Type 1, 2’ or as a covariate if continuous. The F-ratios from the ANCOVA for all transcripts were summarized by averge F-ratio for each variable. Of interest, the slope from the AffyRNAdeg showed the highest average F-ratio compared to all other covariates (Fig 4). The rank of AffyRNAdeg persisted regardless of the type of data normalization used (quantile or grand median centering) or the effect of entering or removing other covariates.

Figure 4.

The sources of variation in an ANCOVA of multiple covariates shows that the RNA degradation accounts for the highest average effect (F-ratio) across the entire transcriptome in ACC measured on an Affymetrix U133A chip. The AffyRNAdeg program (Cope, 2005) provides a slope, which is a microarray chip based indicator of the decline in signal across a transcript, thus a putative index of RNA degradation. The abbreviations for each variable are described in Table 1.

Quality Control Parameters Application In Anterior Cingulate Cortex

We presented evidence that each of the 4 quality control indicators (clinical, tissue, RNA and microarray quality) were significantly correlated to one another (Table 5), but were not perfectly correlated. A multiple covariable analysis of all transcripts showed that a posthoc measure of putative RNA degradation (AffyRNAdeg) accounted for a large proportion of variance in transcript expression.

All 3 quality selection parameters were used simultaneously in the current data set using cut points of AFS = 0, pH ≥ 6.6, and 28S / 18S ≥ 1.5 as threshold criteria for sample selection as described. The “included” set (AFS = 0 AND pH ≥ 6.6 AND 28S / 18S ≥ 1.5) and the “excluded” (AFS ≥ 1, pH < 6.6 and 28S / 18S < 1.5) set were compared. When the poor quality samples were “excluded” each microarray quality control indicator was significantly improved in the “included” group (Table 7). Notably, the microarray quality indicators (all post hoc) were significantly improved in 8 measures performed in two brain regions (Table 7). Additionally, the mitochondrial pathway was significantly over-expressed between the groups. The thresholds appeared to work very well for this data set in two brain regions in selecting high quality microarray data. The “included” set shows that the cut points improved the 4 microarray chip quality indicators (%PC, SF, ACI, and Type 1 / 2) (Table 7), although it is noted that other methods for determining outlier samples could be equally applied at this point. Other methods might include principal component analysis to determine outliers based upon the entire gene expression profile, or performing an ANCOVA with multiple covariates.

Table 7. Eliminating the poorest quality samples.

Example of a strategy that used all three sample cut-points and eliminated the poorest quality samples and chips. The criteria applied for inclusion were: AFS = 0 AND pH ≥ 6.6 AND 28S/18S ≥ 1.5. The samples that passed all three measures were placed into the ‘included’ group and the remaining were placed in the group ‘excluded.’ The two groups were compared by t-test separately in two brain regions. The significant p-values are in bold. The abbreviations are the same as Table 1. The microarray chip quality was improved in the included compared to the excluded samples.

| Clinical Quality | Tissue Quality | RNA Quality | Microarray Chip Quality | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Brain | Criteria | Age | AFS 0 / ≥1 |

pH | PMI (hours) |

Freezer Time (years) |

28S/18S | 3′/5′ GAPDH | 3′/5′ ACTB | RIN** | %PC | SF | ACI | Type 1/2 1 / 2*** |

| ACC | Include (n = 60) | 49.43 (13.76) | N/A | 6.93 (0.16) | 22.96 (7.79) | 3.35 (3.36) | 1.98 (0.22) | 1.46 (0.37) | 2.49 (1.42) | 5.94 (0.93) | 44.00 (4.23) | 1.07 (1.03) | 0.97 (0.02) | 56 / 4 |

| Exclude (n = 38) | 56.26 (12.05) | N/A | 6.66 (0.26) | 25.52 (9.19) | 2.51 (3.41) | 1.51 (0.36) | 2.03 (0.93) | 3.60 (2.13) | 5.67 (1.58) | 41.47 (6.25) | 1.97 (2.08) | 0.92 (0.05) | 12 / 24 | |

| p-value | 0.01 | N/A | N/A | 0.16 | 0.24 | N/A | 0.00074 | 0.0006 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.02 | <0.000005 | <0.000005 | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| CB | Include (n = 59) | 50.20 (13.81) | N/A | 6.94 (0.16) | 23.44 (7.99) | 3.11 (3.24) | 2.06 (0.34) | 1.42 (0.48) | 3.02 (2.74) | 7.11 (1.31) | 45.96 (3.08) | 1.66 (3.10) | 0.98 (0.02) | 57 / 2 |

| Exclude (n = 32) | 54.31 (11.75) | N/A | 6.62 (0.25) | 24.25 (9.26) | 3.22 (3.73) | 1.57 (0.50) | 2.16 (0.97) | 4.54 (3.33) | 5.72 (1.81) | 40.20 (6.86) | 4.24 (5.28) | 0.92 (0.07) | 7 / 25 | |

| p-value | 0.14 | N/A | N/A | 0.68 | 0.89 | N/A | 0.0002 | 0.03 | 0.002 | 0.00006 | 0.02 | 0.0005 | <0.000005 | |

N/A. The a priori selection of quality by AFS, pH, and RNA produced highly significant differences in these 3 measures; therefore the p-value was not shown.

RIN calculation for ACC only included part of the sample due to technical difficulties in the Agilent run.

Type 1 / 2 p-values were calculated by Fisher's exact test.

Some regional variability in the outcome of the quality parameters was noted. As an example, the RIN values for the high quality ‘included’ groups in cerebellum and ACC were not comparable. This was likely due to lower starting RIN values in the ACC the technical result of the revised Agilent software reading of the electropherograms. However correlations were calculated between ACC and cerebellum regions for both RIN (r = 0.42, p <0.01) and SF (r = 0.85, p < 0.0001), thus indicating that across regions there was agreement of these values within subjects.

When we employed the 4 quality cut-offs to the present results the number of samples removed at each stage (Table 8) significantly reduced the study from 98 samples to 57 samples. This reduction in sample size is only one strategy that we have adopted, and may not be practical when working with degraded samples from fixed tissues, or for certain research questions that require use of tissues obtained under less than ideal conditions.

Table 8. Example of number of subjects after applying 4 quality parameters.

An example of applying 4 quality parameters to the results of anterior cingulate for 98 subjects. The methodology shows that 58% of the initial subject pool will pass all 4 parameters. Other methods to adjust for the effects of these quality and other postmortem variables on gene expression can be tested in posthoc analysis such as ANCOVA.

| Clinical Cut-Off | RNA Cut-Off | Tissue Cut-Off | Chip Type Cut-Off | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFS = 0 | 28S / 18S ≥ 1.5 | pH ≥ 6.6 | Type ‘1’ | |

| Number of Subjects Above Cut-Off | 75 | 64 | 60 | 57 |

| Number of Subjects Below Cut-Off | 23 | 14 | 12 | 9 |

Conclusions

We systematically evaluated 4 quality indicators in one study with reference to gene expression results in postmortem brain from two regions. When samples in our study were not balanced well or matched for these quality indicators, the results of pathway analysis identified a brain disorders pathophysiology of mitochondria dysfunction. This pathophysiology is correlated to sample groups that have RNA, clinical, and tissue quality differences. Researchers have implicated mitochondrial-related pathways as a cause in schizophrenia (Prabakaran, Swatton et al. 2004; Altar, Jurata et al. 2005) and bipolar disorder studies (Konradi, Eaton et al. 2004). A slight imbalance in group composition based upon an agonal-pH difference will affect this functional pathway and its related pathways such as apoptosis, proteasome, and chaperone functions (Vawter, Tomita et al. 2006).

The impact of each quality covariable on gene expression may not be linear across wide ranges. As a first approximation researchers have found it useful to examine the readily accessible measures of clinical, tissue and RNA quality prior to microarray analysis and have used matched pairs of subjects or matched groups on these measures. Across a wide range there was a potentially large non-linear variation observed with matching strategies. Investigators might adopt an approach of using all samples and making adjustments with regression models, however this would presume that adequate models exist.

RNA quality found to have a large statistical impact on the amount of variation across all transcripts. The R-script AffyRNAdeg (Cope, 2005) can be used posthoc to assess RNA quality to measure the slope across all transcripts in the 3′/5′ direction instead of only using the beta-actin or GAPDH transcripts. Other chip measures such as present calls and scaling factor accounted for a large proportion of variance across transcripts. Most investigators agree that severely degraded samples will not provide useful data and the findings are compromised when total RNA is degraded (Schoor O 2003; Auer, Lyianarachchi et al. 2003; Buesa C 2004; Tomita, Vawter et al. 2004, Lipska et al., 2006). However, modest degradation of samples such as observed in postmortem brain collections was addressed in the present paper to attempt to describe different strategies to select samples with minimal RNA degradation and with high clinical and tissue quality. It was shown that by removing samples with agonal factors, low pH and degraded RNA higher quality microarray results, based on post hoc measures, will be observed. Consistent recommendations to use the highest quality RNA for gene expression measurements (Bahn, Augood et al. 2001; Auer, Lyianarachchi et al. 2003; Schoor O 2003; Buesa C 2004; Mexal, Berger et al. 2006, Lipska et al., 2006) have led one group of investigators to conclude that “The strongest predictor of gene expression was total RNA quality”(Lipska et al. (2006). Our results are consistent with these reports.

Future microarray knowledge will include how different types of transcripts are affected by postmortem and premortem variables as well as the set of transcripts not affected by these variables. Postmortem brain studies generally utilize one or more of the criteria reviewed for study design and statistical analysis. By adopting only one indicator to accept or reject samples at a certain threshold, an investigator may accept marginal samples. However, in posthoc analysis the impact of these parameters can be determined. We have used multiple criteria to form cohorts of postmortem samples based upon these a priori quality parameters of clinical, tissue, and RNA quality indicators and post hoc microarray indicators. We have also used these same parameters as covariables. For variables with a simple linear relationship these approaches are satisfactory, however, we have not tested non-linear models which may address a larger proportion of variance than the simple linear models. After forming a cohort with cut-off criteria this essentially narrows the range that strong effects can operate, so that the potential for case-control effects can emerge. As an example, we have used a set of criteria to reduce the range of strong effects with the following criteria: AFS = 0; the samples must have both medical records and next of kin interview information; the sample pH is minimally in the range of 6.4 - 6.6; and the RNA integrity measured by Agilent must have a 28S/18S ratio greater than 1.4-1.5 while at the same time taking the RIN value into consideration. We finally use post hoc indicators such as the AffyRNAdeg slope, percent present, scaling factor, ACI, and hierarchical clustering approaches to find outlier chips. These steps taken together will minimize the strong effects of these covariates, but other methods can be utilized to study the same effects and to assess the final quality of the chip.

The evaluation of these 4 quality categories aids in the study design, characterization and assessment of our samples, analysis, and interpretation of results. Not all transcripts are affected to the same degree by these variables as shown in our ANCOVA results. Thus, meaningful data can be derived if posthoc analysis has ruled out confounding effects on specific transcripts. Posthoc use of these quality covariables will help to either strengthen or weaken a candidate gene depending on the impact of the key variables we describe.

The 4 quality indicators are broadly related and therefore using a certain combination of these factors improves the quality of the data set, but might never truly separate the low, moderate, and high quality samples completely. By having access to alternative parameters to assess the quality of both the sample and the microarray data, we present an investigator with covariates for study design, selection criteria, or parameters for matching strategies depending on the nature of the study. These quality parameters may assist future investigators for meta-analysis of postmortem brain gene expression studies, such as those that can be conducted with the gene expression arrays deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Jacque Berndt and the investigators and medical examiners at the Orange County Coroners Office for procurement of brain tissue. We also appreciate the technical contributions of Kathleen Burke, Sharon Burke, Xiaohong Fan, and Phong Nguyen. F. Warren Lovell, M.D, performed a neuropathological evaluation of the postmortem brains. Tissue specimens were processed and stored at the Human Brain and Spinal Fluid Resource Center, Veteran's Medical Center, Los Angeles under the direction of Wallace W. Tourtellotte, M.D., Ph.D. This project is supported by the NIMH Conte Center Grant P50 MH60398, Pritzker Family Philanthropic Fund, William Lion Penzner Foundation (UCI), NIMH Grant #MH54844 (EGJ), W.M. Keck Foundation (EGJ), and the NIMH Program Project MH42251 (SJW and HA). “The authors are members of a research consortium supported by the Pritzker Neuropsychiatric Disorders Research Fund L.L.C. An agreement exists between the fund and the University of Michigan, Stanford University, the Weill Medical College of Cornell University, the Universities of California at Davis, and at Irvine, to encourage the development of appropriate findings for research and clinical applications”

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Altar CA, Jurata LW, Charles V, Lemire A, Liu P, Bukhman Y, Young TA, Bullard J, Yokoe H, Webster MJ, Knable MB, Brockman JA. Deficient hippocampal neuron expression of proteasome, ubiquitin, and mitochondrial genes in multiple schizophrenia cohorts. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(2):85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer H, Lyianarachchi S, Newsom D, Klisovic MI, Marcucci G, Kornacker K, Marcucci U. Chipping away at the chip bias: RNA degradation in microarray analysis. Nat Genet. 2003;35(1):106. doi: 10.1038/ng1203-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahn S, Augood SJ, Ryan M, Standaert DG, Starkey M, Emson PC. Gene expression profiling in the post-mortem human brain--no cause for dismay. J Chem Neuroanat. 2001;22(1-2):79–94. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(01)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T, Cheadle C, Wood WB, Teichberg D, Donovan DM, Freed WJ, Becker KG, Vawter MP. Assembly and use of a broadly applicable neural cDNA microarray. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2001;18(2-3):127–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton AJ, P R, Najlerahim A, Harrison PJ. Pre- and postmortem influences on brain RNA. J Neurochem. 1993;61(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger A, Stierkorb E, Nickenig G. The role of the AUUUUA hexamer for the posttranscriptional regulation of the AT1 receptor mRNA stability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330(3):805–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein P, P S, Ross J. The poly(A)-poly(A)-binding protein complex is a major determinant of mRNA stability in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9(2):659–670. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird ED, S E, Barnes J, MacKay AV, Iversen LL, Shepherd M. Increased brain dopamine and reduced glutamic acid decarboxylase and choline acetyl transferase activity in schizophrenia and related psychoses. Lancet. 1977;2(8049):1157–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91542-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad BM. Low-level analysis of high-density oligonucleotide array data : background, normalization and summarization. 2004;xiv leaves. [Google Scholar]

- Breese CR, Marks MJ, Logel J, Adams CE, Sullivan B, Collins AC, Leonard S. Effect of smoking history on [3H]nicotine binding in human postmortem brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282(1):7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, P J, Moritz G, Allman CJ, Roth C, Schweers J, Balach L. The validity of diagnoses obtained through the psychological autopsy procedure in adolescent suicide victims: use of family history. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87(2):118–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buesa C, M T, Subirada F, Barrachina M, Ferrer I. DNA chip technology in brain banks: confronting a degrading world. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63(10):1003–1014. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.10.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunney WE, B B, Vawter MP, Tomita H, Li J, Evans SJ, Choudary PV, Myers RM, Jones EG, Watson SJ, Akil H. Microarray technology: a review of new strategies to discover candidate vulnerability genes in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(4):657–66. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke WJ, O MK, Chung HD, Harmon SK, Miller JP, Berg L. Effect of pre- and postmortem variables on specific mRNA levels in human brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1991;11(1):37–41. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(91)90018-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter DE, Robinson JF, Allister EM, Huff MW, Hegele RA. Quality assessment of microarray experiments. Clin Biochem. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catts VS, Catts SV, Fernandez HR, Taylor JM, Coulson EJ, Lutze-Mann LH. A microarray study of post-mortem mRNA degradation in mouse brain tissue. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope L. Function to assess RNA degradation in Affymetrix GeneChip data.: AffyRNAdeg. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett RJ, L A, Sterett R, Tollefsbol G, Garcia D. Effect of hypoxia on glucose-modulated cerebral lactic acidosis, agonal glycolytic rates, and energy utilization. Pediatr Res. 1996;39(3):477–86. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199603000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock N, Jones I. Genetics of bipolar disorder. J Med Genet. 1999;36(8):585–94. doi: 10.1136/jmg.36.8.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings TJ, S J, Yoon LW, Szymanski MH, Hulette CM. Recovery and expression of messenger RNA from postmortem human brain tissue. Mod Pathol. 2001;14(11):1157–61. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M, Wang P, Boyd AD, Kostov G, Athey B, Jones EG, Bunney WE, Myers RM, Speed TP, Akil H, Watson SJ, Meng F. Evolving gene/transcript definitions significantly alter the interpretation of GeneChip data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(20):e175. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deep-Soboslay A, A M, Martin CE, Bigelow LB, Herman MM, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE. Reliability of psychiatric diagnosis in postmortem research. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(1):96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumur CI, N S, Best AM, Archer KJ, Ladd AC, Mas VR, Wilkinson DS, Garrett CT, Ferreira-Gonzalez A. Evaluation of quality-control criteria for microarray gene expression analysis. Clin Chem. 2004;50(11):1994–2002. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.033225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erraji-Benchekroun L, Underwood MD, Arango V, Galfalvy H, Pavlidis P, Smyrniotopoulos P, Mann JJ, Sibille E. Molecular aging in human prefrontal cortex is selective and continuous throughout adult life. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(5):549–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SJ, Datson NA, Kabbaj M, Thompson RC, Vreugdenhil E, De Kloet ER, Watson SJ, Akil H. Evaluation of Affymetrix Gene Chip sensitivity in rat hippocampal tissue using SAGE analysis. Serial Analysis of Gene Expression. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16(3):409–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford LP, Bagga PS, Wilusz J. The poly(A) tail inhibits the assembly of a 3′-to-5′ exonuclease in an in vitro RNA stability system. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(1):398–406. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz DT, Bergman N, Kilpatrick WJ, Wilusz CJ, Wilusz J. Messenger RNA decay in Mammalian cells: the exonuclease perspective. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2004;41(2):265–78. doi: 10.1385/CBB:41:2:265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier L, Irizarry R, Cope L, Boldstad B. Description of Affy. 2005. pp. 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum D, Colangelo C, Williams K, Gerstein M. Comparing protein abundance and mRNA expression levels on a genomic scale. Genome Biol. 2003;4(9):117. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-9-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissom SF, Lobenhofer EK, Tucker CJ. A qualitative assessment of direct-labeled cDNA products prior to microarray analysis. BMC Genomics. 2005;6(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakak Y, Walker JR, Li C, Wong WH, Davis KL, Buxbaum JD, Haroutunian V, Fienberg AA. Genome-wide expression analysis reveals dysregulation of myelination-related genes in chronic schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(8):4746–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081071198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JA, W P, Winblad B, Gezelius C, Bring G, Eriksson A. The patients dying after long terminal phase have acidotic brains; implications for biochemical measurements on autopsy tissue. J Neural Transm. 1985;61(3-4):253–64. doi: 10.1007/BF01251916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PJ, H P, Eastwood SL, Burnet PW, McDonald B, Pearson RC. The relative importance of premortem acidosis and postmortem interval for human brain gene expression studies: selective mRNA vulnerability and comparison with their encoded proteins. Neurosci Lett. 1995;200(3):151–154. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12102-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PJ, P A, Barton AJ, Lowe SL, Najlerahim A, Bertolucci PH, Bowen DM, Pearson RC. Terminal coma affects messenger RNA detection in post mortem human temporal cortex. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1991;9(1-2):161–164. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(91)90143-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollams EM, Giles KM, Thomson AM, Leedman PJ. MRNA stability and the control of gene expression: implications for human disease. Neurochem Res. 2002;27(10):957–80. doi: 10.1023/a:1020992418511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosack DA, Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome Biol. 2003;4(10):R70. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-10-r70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynd MR, Lewohl JM, Scott HL, Dodd PR. Biochemical and molecular studies using human autopsy brain tissue. J Neurochem. 2003;85(3):543–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbeaud S, G E, Boulanger V, Barlet X, Zaborski P, Eveno E, Mueller O, Schroeder A, Auffray C. Towards standardization of RNA quality assessment using user-independent classifiers of microcapillary electrophoresis traces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(6):e56. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isometsa E. Psychological autopsy studies--a review. Eur Psychiatry. 2001;16(7):379–85. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(01)00594-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto K, Bundo M, Kato T. Altered expression of mitochondria-related genes in postmortem brains of patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, as revealed by large-scale DNA microarray analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(2):241–53. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SA, Morgan DG, Finch CE. Extensive postmortem stability of RNA from rat and human brain. J Neurosci Res. 1986;16(1):267–80. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490160123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston NL, C J, Shore AD, Torrey EF, Yolken RH. Multivariate analysis of RNA levels from postmortem human brains as measured by three different methods of RT-PCR. Stanley Neuropathology Consortium. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;77(1):83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)00115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]