Abstract

Exogenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) enhances Ca2+ signaling and cell proliferation in human airway smooth muscle (ASM), especially with inflammation. Human ASM also expresses BDNF, raising the potential for autocrine/paracrine effects. The mechanisms by which ASM BDNF secretion occurs are not known. Transient receptor potential channels (TRPCs) regulate a variety of intracellular processes including store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE; including in ASM) and secretion of factors such as cytokines. In human ASM, we tested the hypothesis that TRPC3 regulates BDNF secretion. At baseline, intracellular BDNF was present, and BDNF secretion was detectable by ELISA of cell supernatants or by real-time fluorescence imaging of cells transfected with GFP-BDNF vector. Exposure to the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα (20 ng/ml, 48h) or a mixture of allergens (ovalbumin, house dust mite, Alternaria, and Aspergillus extracts) significantly enhanced BDNF secretion and increased TRPC3 expression. TRPC3 knockdown (siRNA or inhibitor Pyr3; 10µM) blunted BDNF secretion, and prevented inflammation effects. Chelation of extracellular Ca2+ (EGTA; 1mM) or intracellular Ca2+ (BAPTA; 5µM) significantly reduced secreted BDNF, as did knockdown of SOCE proteins STIM1 and Orai1 or plasma membrane caveolin-1. Functionally, secreted BDNF had autocrine effects suggested by phosphorylation of high-affinity tropomyosin related kinase TrkB receptor, prevented by chelating extracellular BDNF with chimeric TrkB-Fc. These data emphasize the role of TRPC3 and Ca2+ influx in regulation of BDNF secretion by human ASM and the enhancing effects of inflammation. Given BDNF effects on Ca2+ and cell proliferation, BDNF secretion may contribute to altered airway structure and function in diseases such as asthma.

Keywords: Neurotrophin, Lung, Inflammation, Asthma, Tropomyosin-related kinase, Signaling

1. Introduction

Primarily recognized and described in the nervous system, neurotrophins (NTs) are growth factors important for neuronal development and function [1–3]. There is now increasing evidence that NTs and their receptors are expressed in non-neuronal tissues including the airway [4–9], but their function is under investigation. We previously reported that brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and its high-affinity tropomyosin related kinase (TrkB) as well as low-affinity pan-NT p75NTR receptors are expressed by human airway smooth muscle (ASM) [6, 7], and that exogenous BDNF enhances [Ca2+]i responses to agonist [7] and cell proliferation [10]. Furthermore BDNF potentiates the effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNFα) [6, 10, 11]. While these effects of exogenous BDNF are clearly relevant to inflammatory airway diseases such as asthma, characterized by enhanced airway contractility, ASM cell proliferation and remodeling, the sources and mechanisms of regulation of BDNF in the airway are not clear.

The classic understanding is that NTs such as nerve growth factor (NGF) and BDNF are secreted from nerve endings and activate both Trk and p75NTR receptors, leading to altered cell growth and other functions [12–16]. BDNF has now been shown to be expressed by several airway cell types including epithelium, immune cells, nerves and even ASM [5, 17–20]. Furthermore, sputum and/or bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL) from patients with asthma, allergic rhinitis or chronic cough show elevated levels of BDNF [17, 21–24] suggesting that the different airway cell types may actually secrete BDNF. Here, Kemi et al. [20] previously found BDNF in the extracellular medium of human ASM cells. While secretory mechanisms for BDNF have been examined in neurons, and involve vesicular release [25], the mechanisms underlying BDNF secretion by non-neuronal cells, particularly in the lung, are not clear. The relevance of understanding BDNF secretion in the airway lies in the increasing recognition that local growth factor production can have pleiotropic effects in the context of inflammation, especially given the evidence that a range of airway cells express NT receptors and can thus respond to local factor production [5].

In neuronal tissues, a major stimulus for NT secretion is elevation in [Ca2+]i typically following electrical stimulation leading to vesicular release [26]. While it is likely unnecessary for ASM cells to rapidly secrete NTs, vesicular secretion pathways do exist in airway cells [27], and are regulated by a number of complex mechanisms. The mechanisms by which BDNF release occur in non-neuronal tissues are unknown. The highly regulated, vesicular release of neurons [25, 28] may not be relevant in ASM, and it is beyond the scope of any single study to examine the many complex secretory pathways that may exist in ASM. However, [Ca2+]i is known to modulate secretion in general, and of BDNF in neurons and vasculature.[29, 30] Thus mechanisms that regulate [Ca2+]i in ASM may play a role in modulating BDNF secretion. In this regard, in non-ASM cells, recent studies suggest a role for canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) channels in fluid secretion and in exocytosis of other intracellular proteins [31]. We have previously demonstrated that human ASM expresses a variety of TRPC channels, but TRPC3 is particularly important for modulating store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) [32]. Relevant to airway disease, inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα increase TRPC3 expression [32, 33] while BDNF modulates TRPC3 function in human ASM [6]. In non-neuronal cells, [34, 35] TRPC3 has been shown to regulate secretion, but its non-SOCE role in ASM is not known. Accordingly, in the present study, we hypothesized that TRPC3 is important in BDNF secretion by ASM, and tested this hypothesis in human ASM in the context of enhanced BDNF secretion in the presence of inflammation.

Material and Methods

1.1. Human ASM Cells

Previously described techniques for isolating human ASM cells from lung samples incidental to patient thoracic surgery were used [6, 7]. Briefly, under a protocol approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, surgical lung specimens of patients undergoing pneumenectomies or lobectomies for focal, non-infectious disease were obtained from surgical pathology at St. Marys Hospital of the Mayo Clinic, immediately following diagnosis by the pathologist. To avoid confounding issues relating to airway pathology, samples were limited to those from patients without clinical diagnoses of asthma, COPD or fibrosis. With the pathologist’s aid, normal areas of 3rd to 6th generation bronchi were identified, dissected free of adventitia, and placed in cold Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES and 2 mM Ca2+. Under microscopy, the epithelium was denuded in these bronchial rings, the ASM layer removed by blunt dissection, minced and ASM cells enzymatically dissociated. Cells were seeded into culture flasks or other chambers for experimentation, and maintained under usual culture conditions in phenol red-free DMEM/F-12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS. Prior to experimentation, cells were serum starved for 48h and only cells of passages 1–3 were used. Maintenance of ASM phenotype with subculture was verified as previously described [36] and involved verification of smooth muscle actin and myosin but absence of fibroblast markers (fibroblast surface protein) or epithelial markers (E-cadherin).

1.2. Western Analysis

Standard SDS-PAGE (Criterion Gel System; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA; 4–15% gradient gels) and PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad) transfer techniques were used. Membranes were blocked with milk in TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 and blotted. GAPDH was used as a loading control. For secondary antibody detection, either horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies with chemiluminescence substrate or far-red fluorescent dye conjugated antibodies were used. Blots were imaged on a Kodak Image Station 4000MM (Carestream Health, New Haven, CT) or a LiCor OdysseyXL system, and quantified using densitometry.

For immunoprecipation studies of phosphorylated proteins, ASM cell lysates in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail were immunoprecipitated using phosphotyrosine antibody 4G10 (Millipore, 06–427) and immunocomplexes captured using catch release kit (Millipore, 17–500) per manufacturer instructions. Thereafter, samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE, PVDF membrane transfer and immunoblotted against TrkB antibody (Neuromics, GT15080) with antibody-reactive bands detected as above.

1.3. ELISA

Sandwich ELISA for BDNF in cell supernatants was performed (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) using standard, manufacturer-provided protocols. Initial ELISA of undiluted supernatants suggested BDNF levels at the lower limits of detection of the kit (<20 pg/ml). Therefore, supernatants were concentrated 12-fold prior to ELISA, and measurements corrected post hoc. Colorimetric quantification of BDNF levels was performed on a FlexStation3 microplate reader at 450 nm (wavelength correction set to 540 nm) and compared to a standard curve based on manufacturer-supplied recombinant BDNF. Confirmation of BDNF in the supernatant was performed using Western analysis of the same concentrated samples (Millipore Centriprep).

1.4. Pro-inflammatory stimulation

Cells made serum-free for at least 24h were exposed to medium only, 20 ng/ml TNFα or a mixture of allergens (10 µg each of ovalbumin, and of extracts from Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus fumigatus and Dermatophagoides farinae (house dust mite)) for 24h. For inhibition or siRNA studies, pro-inflammatory stimuli followed such interventions.

1.5. siRNA Transfection

ASM cells at ~50% confluence were made serum- and antibiotic-free for 24 h before transfection with 300 pmoles of siRNA against TRPC3, Orai1, STIM1 or caveolin-1 (Ambion-Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX) or with a HA-tagged TRPC3 overexpression plasmid using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Scrambled siRNA was used to verify lack of off-target effects. Six hours after transfection, fresh growth medium was added and cells grown overnight. Serum deprivation was then maintained for 48h followed by experimentation.

1.6. GFP-BDNF Transfection, Imaging, and Analysis

Serum-free ASM cells at ~50% confluence were transfected with 300 pM of a GFP-BDNF vector[30, 37, 38] using Lipofectamine reagent. An empty vector as well as GFP alone were used for transfection controls. Samples were visualized using a Nikon real-time fluorescence imaging system, with a 100X/1.3NA oil immersion lens, standard GFP filters and a high-sensitivity 14-bit digital camera. GFP-BDNF transfected cells were exposed to vehicle, TNFα (as above) or Pyr3 and then acutely exposed to 1 µM of the bronchoconstrictor agent acetylcholine (ACh) and images acquired at 1 Hz.

Image analysis was performed using Nikon Elements software. In image sets of GFPBDNF transfected ASM cells, peri-membranous regions showing punctate fluorescence were identified, and small regions of interest (ROI) were drawn. At least 10 ROIs that included the plasma membrane (i.e. covered extracellular and intracellular regions) were drawn allowing measurements of fluorescence changes representing BDNF release from the immediate subplasma membrane areas (see Results).

1.7. Materials

BDNF antibody (Abcam rabbit anti TrkB, ab33655); GAPDH antibody (Cell Signaling mouse anti-GAPDH, #2118); TRPC3 antibody (Alomone, ACC-016); Orai1 antibody (Alomone, ACC-060); STIM1 antibody (Abcam, ab62031). Pyr3 (TRPC3 inhibitor), BAPTA, EGTA were obtained from Calbiochem (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown NJ) and Xestospongin (IP3R inhibitor) from Sigma-Aldrich.

1.8. Statistical Analyses

All experiments were performed in quadruplicate on cells isolated from 4 different individuals (n = 4). Analysis of results was accomplished using one-way ANOVA with repeated measures or Bonferroni correction where appropriate. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05; all values are expressed as means ± SE.

2. Results

2.1. BDNF Release by Human ASM is Increased by Inflammatory Stimuli

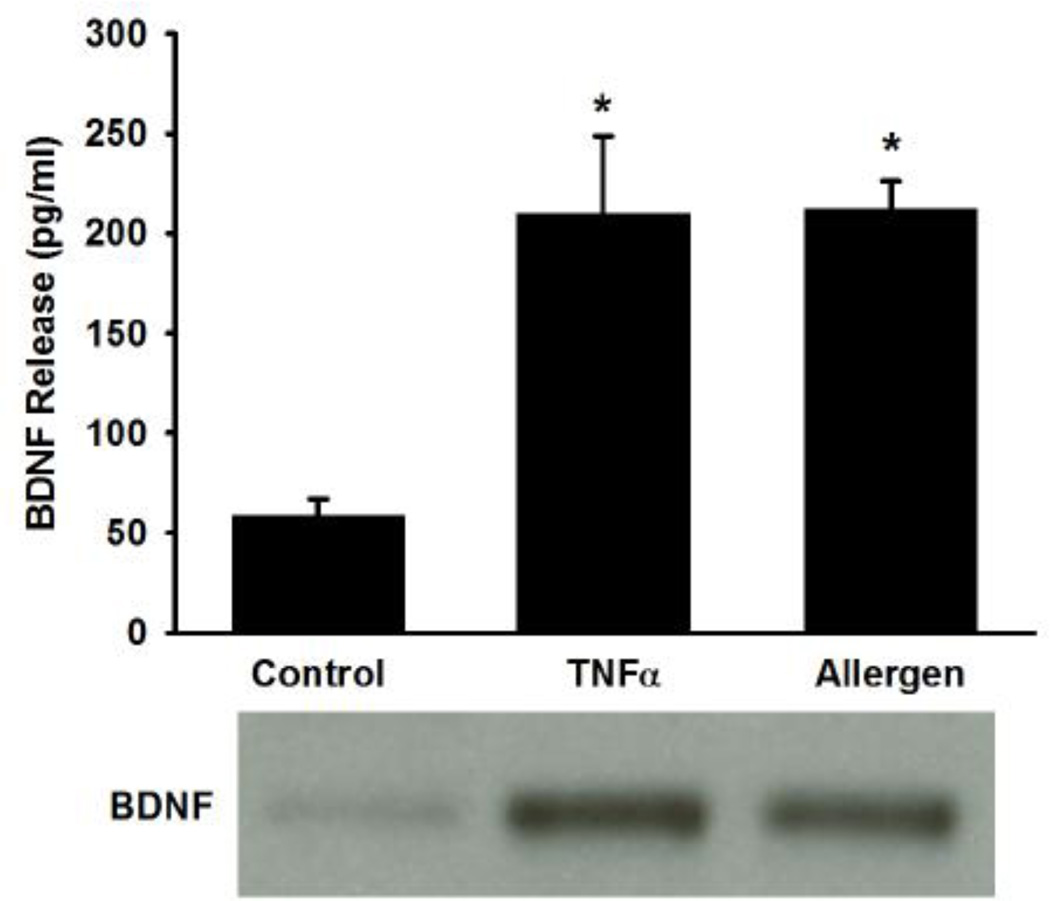

At baseline, control ASM cells displayed only a small amount of BDNF in the supernatant, suggesting minimal release. In cells exposed to TNFα, or particularly to mixed allergens, there was a substantial increase in the amount of secreted BDNF as detected by ELISA as well as Western analysis of the supernatant (Figure 1; p<0.05 for either stimulation).

Figure 1.

Release of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) by human airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells. At baseline, only a small amount of BDNF was detected in the supernatant of ASM cell cultures. With exposure to 20 ng/ml tumor necrosis factor (TNFα), or particularly to mixed allergens (see Methods for details), there was a substantial increase in secreted BDNF as detectable by ELISA and Western analysis. Values in bar graph are means ± SE. * indicates significant TNFα or mixed allergen effect (P<0.05).

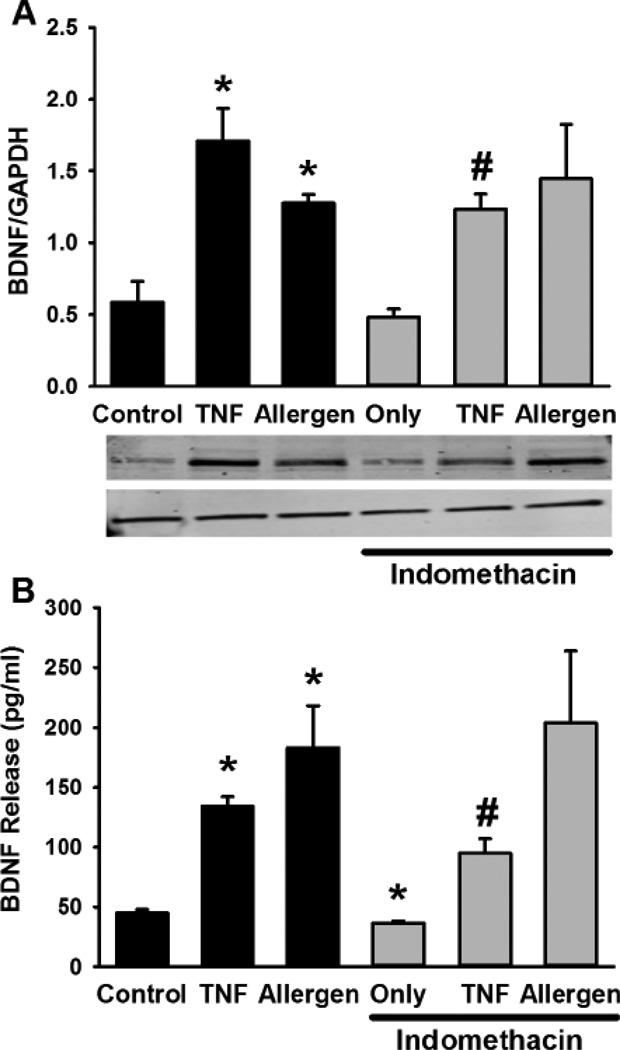

While these data demonstrated BDNF secretion, in parallel studies, Western analysis of ASM cell lysates showed baseline intracellular expression of BDNF protein that was increased by TNFα and mixed allergens (Figure 2). Obviously, a number of mechanisms could contribute to such increases. Based on a previous study suggesting a role for cyclooxygenase in BDNF enhancement by cytokines [20], we explored the effect of indomethacin (10 µM) and found reduced BDNF expression and secretion at baseline as well as with TNFα stimulation (but not with mixed allergens; Figure 2; p<0.05 for indomethacin effect).

Figure 2.

Mechanism of BDNF expression and release in ASM cells. Exposure to TNFα or mixed allergens significantly increased intracellular BDNF expression (Western analysis; A) as well as its release (B). Inhibition of cyclooxygenase by indomethacin substantially blunted TNFα enhancement of BDNF expression or release but not that with mixed allergens. Values in bar graph are means ± SE. * indicates significant TNFα or mixed allergen effect, # indicates significant inhibitor effect (P<0.05).

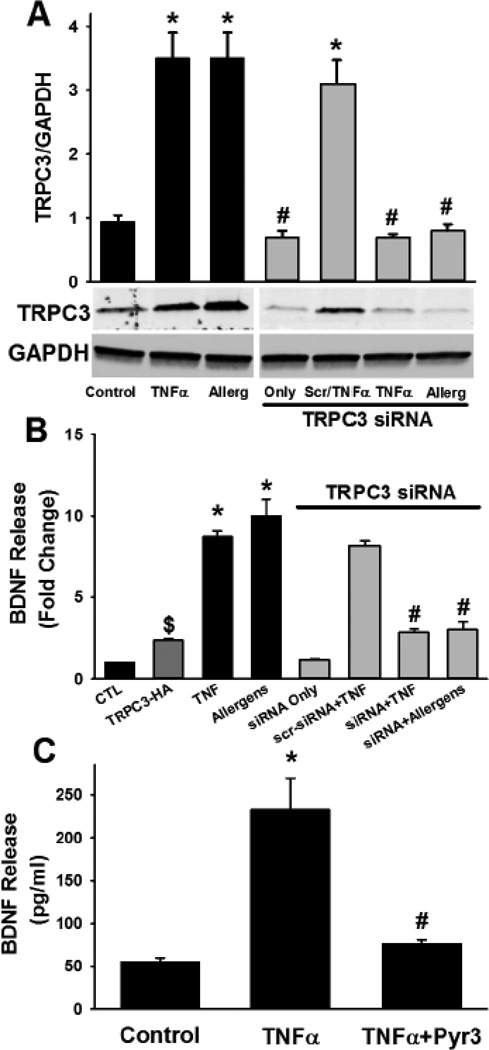

2.2. Role of TRPC3 in BDNF Release

Exposure to ASM cells to TNFα, or particularly to mixed allergens resulted in a substantial increase in TRPC3 protein expression (Figure 3; p<0.05). siRNA knockdown of TRPC3 also blunted BDNF secretion in these groups to an extent comparable to Pyr3 (Figure 3; p<0.05 for siRNA effect). siRNA efficacy for TRPC3 knockdown was verified by Western analysis (Figure 3). In contrast, scrambled siRNA for TRPC3 did not alter its expression, and consistently did not significantly influence the enhancement of BDNF release by TNFα (Figure 3). Non-specific effects of Pyr3 on TRPC3 expression were also absent. Similarly, pharmacological inhibition of TRPC3 with 5 µM Pyr3 for 24h substantially decreased the enhancement of BDNF secretion by TNFα (Figure 3; p<0.05 for Pyr3 effect). In contrast to the reduction in BDNF release when TRPC3 was suppressed, overexpression of TRPC3 using the HA-tagged construct enhanced baseline BDNF release (Figure 3; p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Role of canonical transient receptor channel (TRPC3) in BDNF release. In ASM cells, exposure to TNFα or mixed allergens significantly increased TRPC3 expression (A). siRNA targeting TRPC3 substantially blunted its protein expression, regardless of the inflammatory exposure. Scrambled siRNA did not have an inhibitory effect (TNFα exposure shown). In the presence of TRPC3 siRNA, BDNF secretion by ASM cells was significantly blunted, even in the presence of TNFα or mixed allergens, while scrambled siRNA did not have an inhibitory effect (B). In contrast, over-expression of TRPC3 using an HA-tagged construct increased BDNF release (dark gray bar in B). Separately, pharmacological inhibition of TRPC3 using Pyr3 substantially blunted the enhancing effects of TNFα on BDNF release. Values in bar graph are means ± SE. * indicates significant TNFα or mixed allergen effect, # indicates significant siRNA or Pyr3 effect (P<0.05).

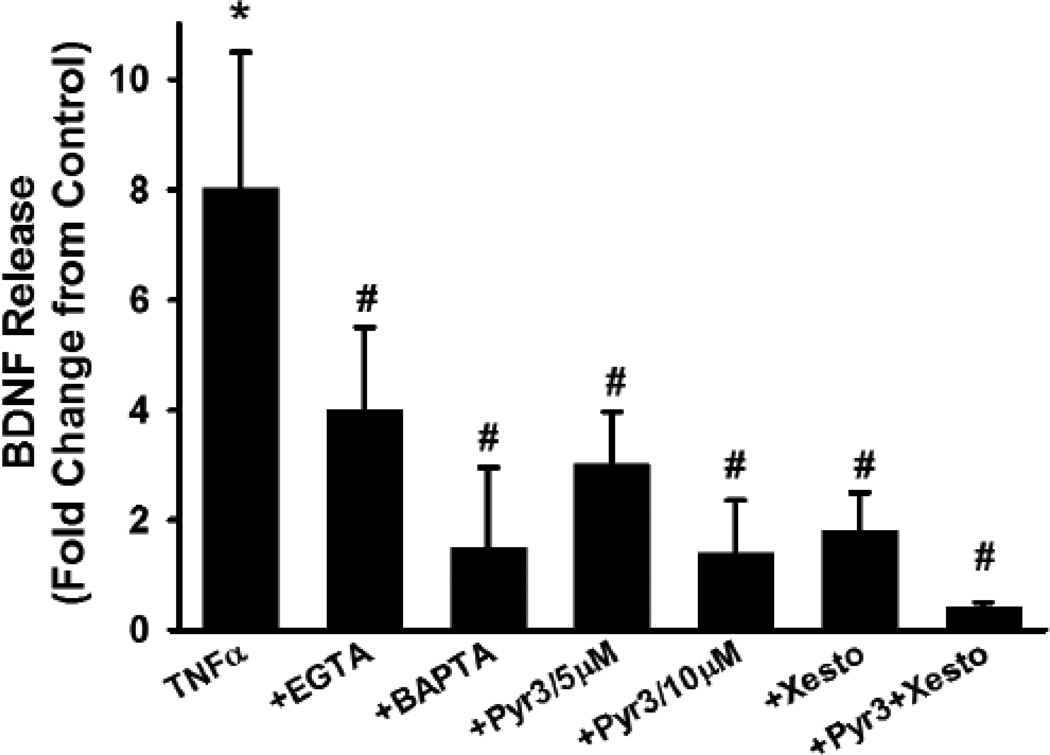

In other cell types, BDNF secretion is Ca2+ dependent. A major role for TRPC3 in human ASM is Ca2+ influx[33, 39], while TNFα is known to increase TRPC3 expression and function [32]. To determine the role of [Ca2+]i in BDNF release, and the influence of TRPC3 in this regard, ASM cells were exposed to vehicle or TNFα and then to one of the following to control [Ca2+]i or its regulation: medium only, 5 µM BAPTA/AM (to clamp [Ca2+]i), EGTA in zero extracellular Ca2+ (to prevent Ca2+ influx), or XeC (to inhibit sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release via IP3R). Each of these interventions resulted in significant decrease in BDNF release albeit to different extents (Figure 3; p<0.05). Inhibition of TRPC3 with 5 or 10 µM Pyr3 with these interventions had relatively smaller effect on BDNF release compared to Pyr3 alone (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Role of [Ca2+]i regulatory mechanisms in BDNF release. ASM cells were exposed to vehicle or TNFα and then to one of the following to control [Ca2+]i or its regulation: medium only, 5 µM BAPTA/AM (to clamp [Ca2+]i), EGTA in zero extracellular Ca2+ (to prevent Ca2+ influx), or Xestospongin C (to inhibit sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release via IP3 receptor channels) with or without concurrent Pyr3 inhibition. Each of these interventions resulted in significant decrease in BDNF release albeit to different extents. Values in bar graph are means ± SE. * indicates significant TNFα or mixed allergen effect, # indicates significant inhibitor effect (P<0.05).

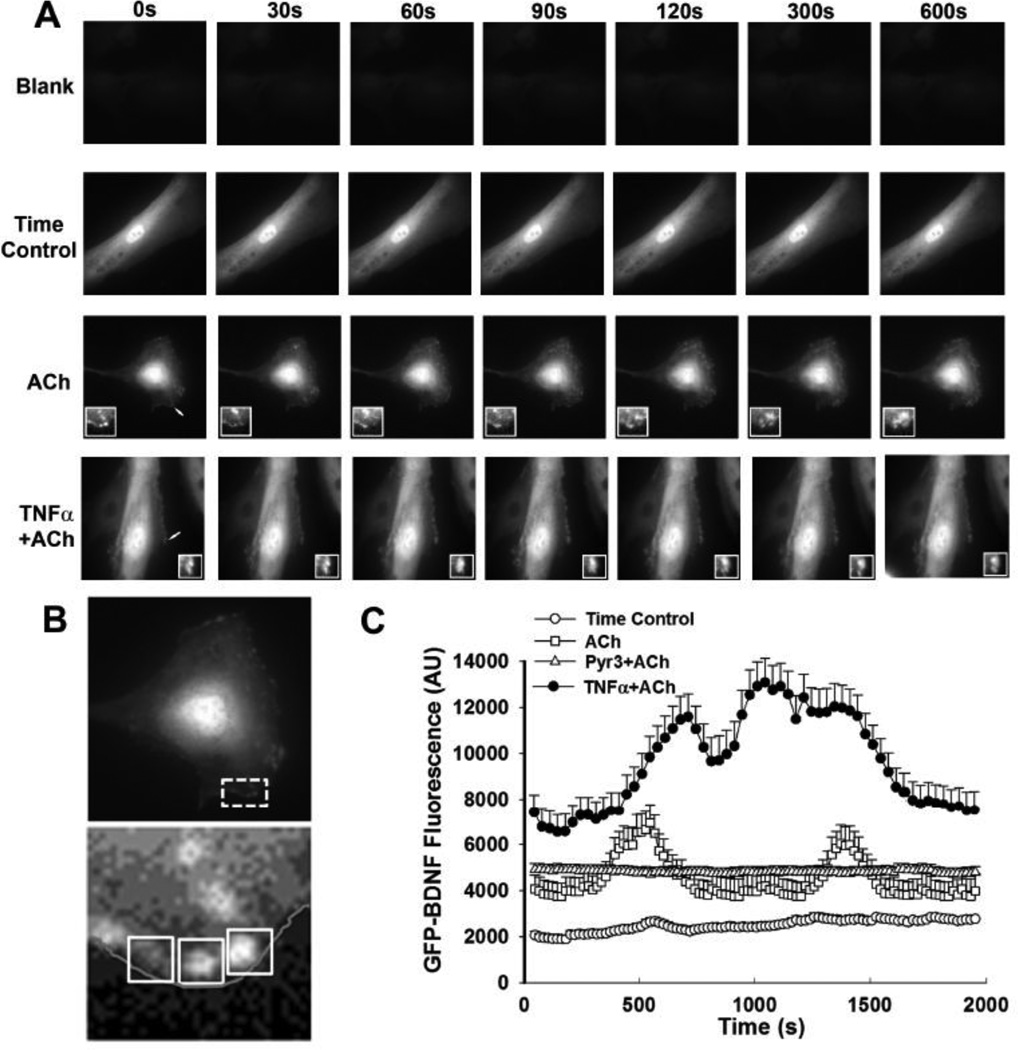

Based on the above findings, BDNF release was visualized and quantified in GFP-BDNF transfected cells. At baseline, in control ASM cells, diffuse staining of BDNF was visible (likely reflecting the overexpression from the vector). However, the cell borders showed areas of punctate pattern resembling vesicles (Figure 5). Regions of interest were defined in these peri-membranous areas to determine changes in GFP-BDNF (Figure 5B). Following stimulation with 1 µM ACh, peri-membranous areas with pre-existing punctate fluorescence showed rapid decrease in fluorescence, while adjacent peri-membranous areas with initially lower fluorescence showed rapid accumulation of punctate structures followed by merging of vesicle-appearing structures with the cell membrane (e.g. see 3rd insets in row of images in Figure 5A showing effects of ACh). In cells exposed to TNFα, there was visibly greater baseline presence of puncate fluorescence at cell borders and a more accelerated fluorescence reduction as well as accumulation of new fluorescent areas following ACh stimulation in the continued presence of TNFα (Figure 5B). These changes in the different cell groups were reflected by overall fluctuations in fluorescence (Figure 5). The extent of vesicular presence or their release by ACh in the presence or absence of TNFα were substantially blunted by Pyr3 (Figure 5 shows for non-TNFα exposed cells) or TRPC3 siRNA (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Release of BDNF by human ASM cells. In ASM cells transfected with GFP-BDNF construct, release of BDNF was visualized using time-lapse fluorescence microscopy. Compared to blank vector transfected cells, GFP-BDNF fluorescence was visible as a diffuse pattern (likely representing over-expression) with areas of punctate fluorescence near the plasma membrane that were largely static in the absence of stimulation (A). Arrows indicate regions enlarged in insets. Stimulation with ACh resulted in rapid changes in peri-membranous fluorescence, reflected by reduced fluorescence in previously bright areas, and increased fluorescence in others (e.g. 3rd row of images and insets in panel A). These data suggest vesicular release of BDNF with additional contributions of vesicular trafficking. In cells exposed overnight to TNFα, baseline fluorescence and punctate patterns were more obvious, and the extent of release was greater following ACh stimulation. These observations were reflected by fluorescence measurements within regions of interest (ROIs) in the peri-membranous areas (B; ROIs from sample ACh exposure series and associated inset). Interestingly, peri-membranous fluorescence changes fluctuated with time (C), with TNFα-exposed cells showing higher levels. Inhibition with Pyr3 prevented changes in fluorescence changes induced by ACh. Values are means + SE. * indicates significant TNFα effect (P<0.05).

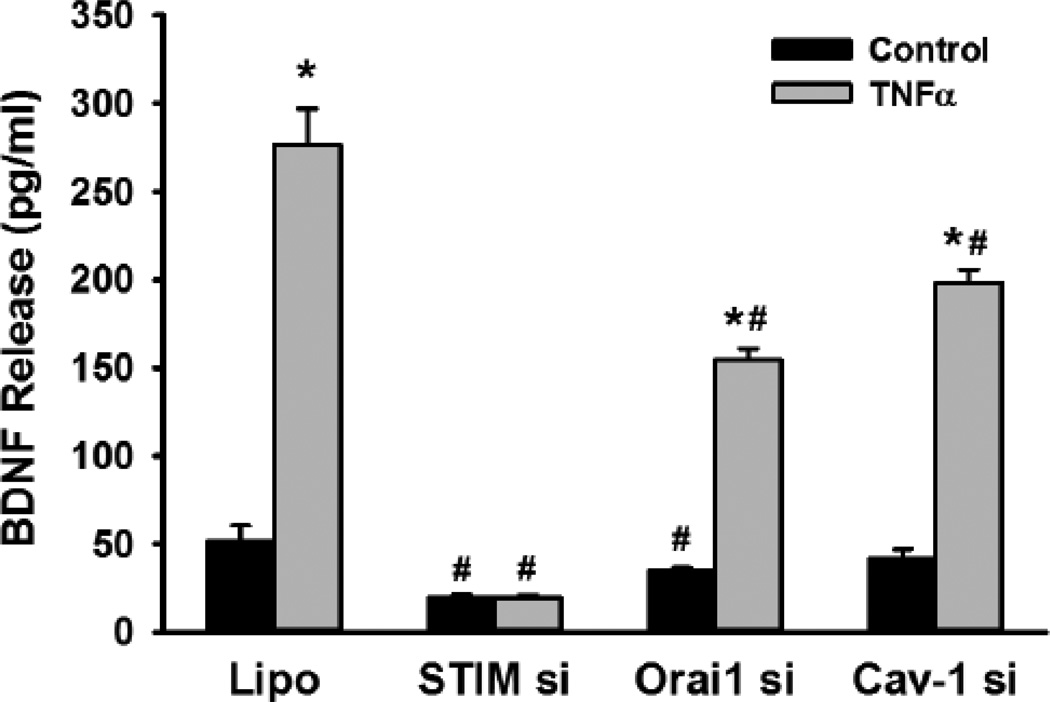

2.3. Role of SOCE in BDNF Release

Recent studies, including our own [40, 41] have shown that SOCE in ASM involves the sarcoplasmic reticulum stromal interaction protein (STIM1) and the plasma membrane protein Orai1. Furthermore, we have found that Orai1 is present within caveolae of human ASM cells, and are regulated by the constitutional protein caveolin-1 [40]. Also, inflammation increases caveolin-1 and Orai1 expression and function in ASM [40]. Accordingly, when we examined the contribution of these mechanisms, we found that siRNA knockdown of STIM1, Orai1 or caveolin-1 all suppressed BDNF release, particularly in the presence of TNFα (Figure 6; p<0.05 for siRNA effects). We have previously demonstrated the efficacy and specificity of these siRNAs [40].

Figure 6.

Role of store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) mechanisms in BDNF secretion. siRNA inhibition of the expression of the SOCE mechanisms STIM1 and Orai1 both blunted BDNF secretion in ASM cells, especially in the presence of TNFα. Separately, siRNA suppression of the plasma membrane caveolar protein caveolin-1, which harbors the Orai1 protein (as well as TRPC3) also, prevented BDNF release, albeit not to the same extent. Values are means + SE. * indicates significant TNFα effect, # indicates significant siRNA effect (P<0.05).

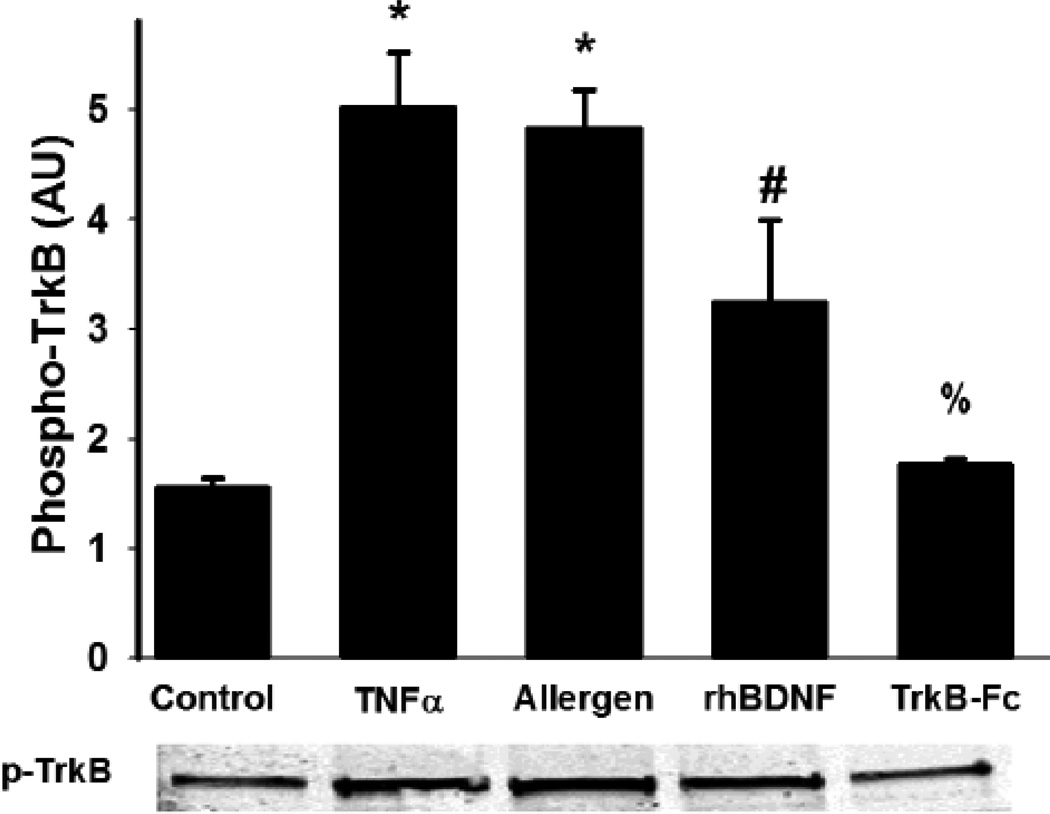

2.4. Functional effect of released BDNF

Exogenous BDNF affects ASM [Ca2+]i and cell proliferation largely via the high-affinity receptor TrkB [6, 7, 10]. Accordingly, we found increased phosphorylation of TrkB in human ASM, particularly with TNFα exposure (Figure 7): effects that were blunted in the presence of the chimeric protein TrkB-Fc which chelates extracellular BDNF (Figure 7; p<0.05 for TrkB-Fc effect).

Figure 7.

Functional effect of BDNF. Immunoprecipitation of the phosphorylated form of the high-affinity BDNF receptor TrkB demonstrated that the secreted BDNF had autocrine effects on ASM. Such effects were blunted by the extracellular BDNF chelator TrkB-Fc (chimeric Fc portion of the TrkB receptor), but enhanced by exogenous, recombinant human BDNF as well as by the enhanced secretion induced by TNFα or allergens. Values are means + SE. * indicates significant TNFα or allergen effect, # indicates exogenous BDNF effect, % indicates TrkB-Fc effect (P<0.05).

3. Discussion

The present study examined the mechanisms by which the neurotrophin BDNF is secreted by human ASM and found that elevated [Ca2+]i, mediated by TRPC3 is particularly important not only in baseline BDNF release, but also in the enhanced secretion of BDNF that occurs with airway inflammation. Furthermore, inflammatory stimuli such as the cytokine TNFα appear to increase BDNF synthesis via mechanisms such as cyclooxygenase, which may further lead to increased BDNF release. Given previous studies demonstrating upregulation of airway BDNF in asthma and allergic diseases, and findings that BDNF can enhance [Ca2+]i, increase cell proliferation and the expression of Ca2+ and force regulatory proteins in ASM, the present study suggest that ASM itself is a source of local BDNF in the airway and can contribute to altered structure and function in the presence of airway inflammation.

NTs such as BDNF are well-known in the nervous system not only as growth factors with genomic effects on neuronal development and function [1–3, 15, 16], but also for their acute, non-genomic effects such as enhanced [Ca2+]i and synaptic transmission [42, 43]. Interesting, NTs can activate several intracellular signaling cascades such as phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K), and mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs) [12–14] which are also important for mediating the effects of inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, that are known to be involved in airway diseases. Accordingly, the increasing evidence that NTs including BDNF, and their receptors (particularly the Trks) are expressed in the lung [5] becomes significant. For example, we previously reported that the BDNF/TrkB system is present and function in human ASM cells [6, 7] such that on the one hand BDNF non-genomically enhances [Ca2+]i responses to agonist [7] and potentiates the effects of TNFα [6] and on the other genomically enhances expression of [Ca2+]i and force regulatory proteins [11]and ASM cell proliferation [10]. While these studies demonstrate that human ASM responds to BDNF regardless of its source, the novelty of the present study lies in the demonstration that ASM is also a source of BDNF that can be modulated in the setting of inflammation.

Previous studies have shown that airway cells such as epithelium, ASM, immune cells, and nerves, are all capable of producing BDNF [5, 17–20]. The relevance of such effects lies in the recent recognition that circulating BDNF levels as well as local receptor expression are increased in asthma [5, 17]. Clinical findings suggest increased NT levels in both sputum and bronchoalveolar lavages of patients with chronic inflammatory airway diseases associated with smoking and with smoke exposure [22, 44] While these studies associate airway disease with elevated BDNF, the question remains as to the source of BDNF and the functional relevance of elevated BDNF. In this regard, NTs derived from airway nerves have been suggested as contributing to neurogenic asthma while those by immune cells are thought to modulate inflammation [17, 45] and thus may be upregulated by environmental factors including inflammation itself. Cytokines (e.g. TNFα) may then indirectly upregulate NT expression and signaling. For example, we have previously shown that TNFα enhances BDNF and TrkB expression in human ASM [6] while Kemi et al. noted increases in different NTs (including BDNF) following stimulation with other cytokines, particularly IL-1β [20]. Functional studies in animals suggest a role for BDNF in airway inflammation, remodeling, and hyperreactivity [46, 47]. The present study now provides novel data demonstrating potential mechanisms by which such BDNF enhancement may occur, and the fact that it may not be just BDNF expression, but its secretion into the extracellular environment. Here, inflammation enhancement of BNDF may involve increased synthesis via mechanisms of interest to airway disease such as cyclooxygenase as demonstrated in the present study, and consistent with previous data [20]. Accordingly, given expression of BDNF receptors in epithelium, ASM, nerves and immune cells [48] ASM-derived BDNF can potentially have autocrine/paracrine effects in the airway that mediate the functional effects of inflammation such as airway hyperresponsiveness and remodeling/cell proliferation. In this regard, the present findings that chelation of secreted BDNF via the chimeric protein TrkBFc (thus competing with cell surface TrkB receptors) prevents TrkB phosphorylation within ASM cells suggests at least an autocrine target for secreted BDNF. Whether this occurs in vivo remains to be determined.

A major, novel finding of the current study is the importance of TRPC3 and [Ca2+]i in BDNF secretion by ASM, particularly in the presence of inflammation. Compared to relatively detailed examination of TRPCs in vascular smooth muscle, less is known regarding TRPCs in normal function of the airway, or in respiratory diseases. Nonetheless, previous studies have examined TRPC isoforms in ASM, and their potential involvement in diseases such as asthma and COPD [33, 49–55]. Studies in ASM of multiple species including humans all show expression of TRPC1, TRPC3, TRPC4, TRPC5, TRPC6 and TRPC7 albeit to different levels [32, 56–60]. However, a majority of functional studies have focused on TRPC3 which is the major component of native non-selective cation channels and thus contributes to elevation of [Ca2+]i in response to agonist stimulation and with store depletion [33, 39]. Limited data demonstrate that TRPC3 regulates resting membrane potential in ASM, such that siRNA knockdown of TRPC3 lowers membrane potential [33, 39]. Importantly, TRPC3 is involved in [Ca2+]i responses to agonists such as ACh [32, 33] where in addition to allowing Ca2+ entry, TRPC3 may also modulate local [Ca2+]i levels in the proximity of the plasma membrane, thus influencing other mechanisms such as Na+/Ca2+ exchange or membrane potential which then enhance influx via L-type Ca2+ channels [61]. In this regard, a recent discovery has been that TRPC3 localizes to caveolae in human ASM [40, 62]. In turn, we have reported that caveolin-1, the constitutive scaffolding protein within caveolae regulates TRPC3 function in terms of Ca2+ influx [62]. Accordingly, the relevance of TRPC3 regulation of BDNF release lies in the fact that TRPC3 can regulate both store- and receptor-operated mechanisms to maintain influx over sustained periods following agonist stimulation and thus substantial enhance BDNF release, particularly in the presence of inflammation.

Given multiple effects of TRPC3, previous studies have examined the importance of altered TRPC3 expression and function in airway diseases. For example, increased TRPC3 expression occurs in airways of patients with asthma [33, 39, 63]. Separately, we have shown that TNFα upregulates TRPC3 expression in human ASM [32] and functionally contributes to TNFα-induced enhancement of [Ca2+]i and thus airway contractility [32]. Accordingly, the findings in our present study that enhanced TRPC3 expression occurs with TNFα exposure are consistent. However, more importantly, such enhanced TRPC3 appears to be important for the increase in BDNF secretion observed not only in the presence of TNFα but also with a more generalized inflammatory stimulus induced by mixed allergens that likely activate a number of cell surface receptors important in airway diseases such as asthma. Here, the role of toll-like receptors (TLRs) are likely, given the fungal allergens used in the present study. Indeed as part of the present study, we found both TLR2 and TLR4 to be expressed by human ASM cells and in fact upregulated by mixed allergen exposure (Supplemental Figure). Whether TLRs act through TRPC3 to induce BDNF release is not known and should be examined in future studies. Overall, the present data suggest a strong link between airway inflammation, TRPC3 and enhanced BDNF release.

In addition to TRPC3 per se, elevated [Ca2+]i seems to be a key player in BDNF release by ASM. In some respect, a role for [Ca2+]i in secretory mechanisms is to be expected. However, secretion of growth factors via presumably a vesicular mechanism (suggested by the realtime imaging of GFP-BDNF) has not been previously shown in human ASM. Here, the observation that peri-membranous GFP-BDNF occurs at baseline and decreases with ACh stimulation is reflective of vesicular release. However, what is also interesting is the finding that other peri-membranous areas with low fluorescence at baseline subsequently demonstrate increased fluorescent aggregates followed by such vesicular release. These complementary observations are highly suggestive of ongoing vesicular release as well as trafficking during agoinst stimulation. Furthermore, the observation that baseline vesicular BDNF is higher in ASM cells with TNFα exposure, as are the amplitudes of fluorescence changes, suggest that inflammation “primes” ASM for BDNF release with agonist stimulation. Accordingly, via this mechanism, enhanced BDNF secretion may contribute to the functional effects of inflammation on airway tone, for example. What remain to be determined in future studies are the mechanisms underlying vesicle release vs. trafficking in ASM, a largely unexplored area.

The link between [Ca2+]i and BDNF secretion appears to also involve other regulatory mechanisms. In ASM, [Ca2+]i regulation involves sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release via IP3R [64] and RyR channels [65] as well as Ca2+ influx via voltage-gated channels [66], receptor-gated channels [67, 68] and SOCE in response to intracellular Ca2+ depletion [60, 69]. In this regard, recent studies, including our own have highlighted the importance of STIM1 and Orai1 in SOCE, with the additional involvement of caveolae and caveolin-1 [40]. Importantly, inflammation appears to increase expression and function of these proteins in ASM [40]. Accordingly, the results of the present study showing reduced BDNF release, particularly in inflammation, when STIM1, Orai1 or caveolin-1 are knocked down by siRNA, all demonstrate the importance of SOCE in modulation of BDNF release. In addition, TRPC3 can also regulate gene expression via multiple signaling intermediates, particularly the Ca2+-calcineurin-NFAT and Ca2+-CaMK pathways [70]. These alternative scenarios remain to be tested in the context of BDNF release by ASM.

The phosphorylation of TrkB and its suppression by the extracellular BDNF chelator shown in the present study demonstrates the autocrine/paracrine capability of ASM-derived BDNF. Accordingly, not only is ASM a local source of BDNF in the airway, but a potential a potential target as well. In this regard, the link between BDNF and TRPC3 and/or SOCE may be of interest in an additional manner. As shown in previous studies, exogenous BDNF can directly influence ASM [Ca2+]i [7]. In neurons, BDNF increases Ca2+ release from intracellular stores [71–73] via the phospholipase C/IP3/IP3R pathway [74]. We previously found that BDNF enhances [Ca2+]i via IP3R channels in human ASM [7]. In pontine neurons, BDNF increases Ca2+ influx via TRPC3 channels [75]. We recently reported that BDNF does enhance SOCE in human ASM as well [11] although a role for TRPC3 or STIM/Orai1 has not been specifically established. Nonetheless, we recently reported that with prolonged exposure, BDNF can enhance expression of IP3R and Orai1 [11]. Accordingly, it is possible that the initial increase in BDNF release induced by agonist stimulation, for example, or by inflammation, can produce autocrine effects of further enhancing TRPC3 function or SOCE, thus sustaining BDNF release. This interesting scenario may be important in that early interference with BDNF, for example by chelating with TrkB-Fc, may interrupt the vicious cycle of elevated [Ca2+]I, release of a pro-contractile growth factor, and downstream genomic effects that contribute to airway hyperresponsiveness and remodeling.

3.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that even non-neuronal tissues such as human ASM actively secrete BDNF, and that inflammatory conditions can stimulate such BDNF production and secretion by enhancing specific signaling pathways including plasma membrane Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms. The implications of BDNF release by ASM cells lies in the recently recognized pro-contractile and pro-proliferative roles of this neurotrophin that may contribute to altered airway structure and function that exists in allergic airway diseases including asthma.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Neurotrophins such as BDNF well-known in neuroscience are being found in the lung

We show that human airway smooth muscle produces and actively secretes BDNF

BDNF secretion involves transient receptor protein channels and calcium entry

Inflammation enhances BDNF secretion that can alter airway structure and function

Airway BDNF can thus mediate inflammation effects in asthma in an autocrine fashion

Acknowledgements

Supported by NIH R01 grant HL088029 and HL056470 (Prakash), HL090595 (Pabelick), and DE017102, 5P20RR017699, and AI097532 (Singh).

Glossary

- ASM

airway smooth muscle

- BAL

bronchial alveolar lavage

- BAPTA

1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N',N'-tetraacetic acid

- BDNF

brain derived neurotrophic factor

- NT

neurotrphins

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- ROI

region of interest

- siRNA

small interference ribose nucleic acid

- SOCE

store-operated calcium entry

- STIM1

stromal interactive molecule one

- TLR

toll like receptor

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- TrkB

tropomyosin related kinase

- TRPC

transient receptor potential channel.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Friedman WJ, Greene LA. Neurotrophin signaling via Trks and p75. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:131–142. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:381–391. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zweifel LS, Kuruvilla R, Ginty DD. Functions and mechanisms of retrograde neurotrophin signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:615–625. doi: 10.1038/nrn1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lommatzsch M, Braun A, Renz H. Neurotrophins in allergic airway dysfunction: what the mouse model is teaching us. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;992:241–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prakash Y, Thompson MA, Meuchel L, Pabelick CM, Mantilla CB, Zaidi S, Martin RJ. Neurotrophins in lung health and disease. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2010;4:395–411. doi: 10.1586/ers.10.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prakash YS, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in TNF-alpha modulation of Ca2+ in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:603–611. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0151OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prakash YS, Iyanoye A, Ay B, Mantilla CB, Pabelick CM. Neurotrophin effects on intracellular Ca2+ and force in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L447–L456. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00501.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ricci A, Felici L, Mariotta S, Mannino F, Schmid G, Terzano C, Cardillo G, Amenta F, Bronzetti E. Neurotrophin and neurotrophin receptor protein expression in the human lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;30:12–19. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0110OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ricci A, Greco S, Amenta F, Bronzetti E, Felici L, Rossodivita I, Sabbatini M, Mariotta S. Neurotrophins and neurotrophin receptors in human pulmonary arteries. J Vasc Res. 2000;37:355–363. doi: 10.1159/000025751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aravamudan B, Thompson M, Pabelick C, Prakash YS. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces proliferation of human airway smooth muscle cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:812–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abcejo AJ, Sathish V, Smelter DF, Aravamudan B, Thompson MA, Hartman WR, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances calcium regulatory mechanisms in human airway smooth muscle. PloS one. 2012;7:e44343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chao MV. The p75 neurotrophin receptor. J Neurobiol. 1994;25:1373–1385. doi: 10.1002/neu.480251106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalb R. The protean actions of neurotrophins and their receptors on the life and death of neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teng KK, Hempstead BL. Neurotrophins and their receptors: signaling trios in complex biological systems. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:35–48. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3099-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luther JA, Birren SJ. Neurotrophins and target interactions in the development and regulation of sympathetic neuron electrical and synaptic properties. Auton Neurosci. 2009;151:46–60. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patapoutian A, Reichardt LF. Trk receptors: mediators of neurotrophin action. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:272–280. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoyle GW. Neurotrophins and lung disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:551–558. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rochlitzer S, Nassenstein C, Braun A. The contribution of neurotrophins to the pathogenesis of allergic asthma. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:594–599. doi: 10.1042/BST0340594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scuri M, Samsell L, Piedimonte G. The role of neurotrophins in inflammation and allergy. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2010;9:173–180. doi: 10.2174/187152810792231913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kemi C, Grunewald J, Eklund A, Hoglund CO. Differential regulation of neurotrophin expression in human bronchial smooth muscle cells. Respir Res. 2006;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barouch R, Appel E, Kazimirsky G, Braun A, Renz H, Brodie C. Differential regulation of neurotrophin expression by mitogens and neurotransmitters in mouse lymphocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;103:112–121. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaudhuri R, McMahon AD, McSharry CP, Macleod KJ, Fraser I, Livingston E, Thomson NC. Serum and sputum neurotrophin levels in chronic persistent cough. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:949–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nassenstein C, Kerzel S, Braun A. Neurotrophins and neurotrophin receptors in allergic asthma. Prog Brain Res. 2004;146:347–367. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)46022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Virchow JC, Julius P, Lommatzsch M, Luttmann W, Renz H, Braun A. Neurotrophins are increased in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after segmental allergen provocation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:2002–2005. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9803023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenberg ME, Xu B, Lu B, Hempstead BL. New insights in the biology of BDNF synthesis and release: implications in CNS function. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12764–12767. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3566-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadakata T, Furuichi T. Developmentally regulated Ca2+-dependent activator protein for secretion 2 (CAPS2) is involved in BDNF secretion and is associated with autism susceptibility. Cerebellum. 2009;8:312–322. doi: 10.1007/s12311-009-0097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proskocil BJ, Sekhon HS, Jia Y, Savchenko V, Blakely RD, Lindstrom J, Spindel ER. Acetylcholine is an autocrine or paracrine hormone synthesized and secreted by airway bronchial epithelial cells. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2498–2506. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuczewski N, Porcher C, Lessmann V, Medina I, Gaiarsa JL. Activity-dependent dendritic release of BDNF and biological consequences. Mol Neurobiol. 2009;39:37–49. doi: 10.1007/s12035-009-8050-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakahashi T, Fujimura H, Altar CA, Li J, Kambayashi J, Tandon NN, Sun B. Vascular endothelial cells synthesize and secrete brain-derived neurotrophic factor. FEBS Lett. 2000;470:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lessmann V, Brigadski T. Mechanisms, locations, and kinetics of synaptic BDNF secretion: an update. Neurosci Res. 2009;65:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bollimuntha S, Selvaraj S, Singh BB. Emerging roles of canonical TRP channels in neuronal function. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;704:573–593. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0265-3_31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White TA, Xue A, Chini EN, Thompson M, Sieck GC, Wylam ME. Role of transient receptor potential C3 in TNF-alpha-enhanced calcium influx in human airway myocytes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:243–251. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0003OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang YX, Zheng YM. Molecular expression and functional role of canonical transient receptor potential channels in airway smooth muscle cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;704:731–747. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0265-3_38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim MS, Lee KP, Yang D, Shin DM, Abramowitz J, Kiyonaka S, Birnbaumer L, Mori Y, Muallem S. Genetic and pharmacologic inhibition of the Ca2+ influx channel TRPC3 protects secretory epithelia from Ca2+-dependent toxicity. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:2107–2115. 2115, e2101–e2104. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lavender V, Chong S, Ralphs K, Wolstenholme AJ, Reaves BJ. Increasing the expression of calcium-permeable TRPC3 and TRPC7 channels enhances constitutive secretion. Biochem J. 2008;413:437–446. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibbons A, Wreford N, Pankhurst J, Bailey K. Continuous supply of the neurotrophins BDNF and NT-3 improve chick motor neuron survival in vivo. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hartmann M, Heumann R, Lessmann V. Synaptic secretion of BDNF after high-frequency stimulation of glutamatergic synapses. EMBO J. 2001;20:5887–5897. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haubensak W, Narz F, Heumann R, Lessmann V. BDNF-GFP containing secretory granules are localized in the vicinity of synaptic junctions of cultured cortical neurons. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 11):1483–1493. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.11.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao JH, Zheng YM, Liao B, Wang YX. Functional role of canonical transient receptor potential 1 and canonical transient receptor potential 3 in normal and asthmatic airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:17–25. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0091OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sathish V, Abcejo AJ, Thompson MA, Sieck GC, Prakash YS, Pabelick CM. Caveolin-1 regulation of store-operated Ca2+ influx in human airway smooth muscle. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:470–478. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00090511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peel SE, Liu B, Hall IP. Orai1 and store operated calcium influx in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:744–749. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0395OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kovalchuk Y, Holthoff K, Konnerth A. Neurotrophin action on a rapid timescale. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:558–563. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rose CR, Blum R, Pichler B, Lepier A, Kafitz KW, Konnerth A. Truncated TrkB-T1 mediates neurotrophin-evoked calcium signalling in glia cells. Nature. 2003;426:74–78. doi: 10.1038/nature01983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kimata H. Passive smoking elevates neurotrophin levels in tears. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2004;23:215–217. doi: 10.1191/0960327104ht445oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frossard N, Freund V, Advenier C. Nerve growth factor and its receptors in asthma and inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;500:453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Braun A, Lommatzsch M, Neuhaus-Steinmetz U, Quarcoo D, Glaab T, McGregor GP, Fischer A, Renz H. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) contributes to neuronal dysfunction in a model of allergic airway inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:431–440. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lommatzsch M, Quarcoo D, Schulte-Herbruggen O, Weber H, Virchow JC, Renz H, Braun A. Neurotrophins in murine viscera: a dynamic pattern from birth to adulthood. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:495–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Braun A, Lommatzsch M, Mannsfeldt A, Neuhaus-Steinmetz U, Fischer A, Schnoy N, Lewin GR, Renz H. Cellular sources of enhanced brain-derived neurotrophic factor production in a mouse model of allergic inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21:537–546. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.4.3670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Banner KH, Igney F, Poll C. TRP channels: emerging targets for respiratory disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;130:371–384. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gosling M, Poll C, Li S. TRP channels in airway smooth muscle as therapeutic targets. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2005;371:277–284. doi: 10.1007/s00210-005-1058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guibert C, Ducret T, Savineau JP. Expression and physiological roles of TRP channels in smooth muscle cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;704:687–706. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0265-3_36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li S, Westwick J, Poll C. Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels as potential drug targets in respiratory disease. Cell calcium. 2003;33:551–558. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nassini R, Materazzi S, De Siena G, De Cesaris F, Geppetti P. Transient receptor potential channels as novel drug targets in respiratory diseases. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;11:535–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nilius B. TRP channels in disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watanabe H. Pathological role of TRP channels in cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2009;134:127–130. doi: 10.1254/fpj.134.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Corteling RL, Li S, Giddings J, Westwick J, Poll C, Hall IP. Expression of transient receptor potential C6 and related transient receptor potential family members in human airway smooth muscle and lung tissue. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;30:145–154. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0134OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ong HL, Brereton HM, Harland ML, Barritt GJ. Evidence for the expression of transient receptor potential proteins in guinea pig airway smooth muscle cells. Respirology. 2003;8:23–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ong HL, Chen J, Chataway T, Brereton H, Zhang L, Downs T, Tsiokas L, Barritt G. Specific detection of the endogenous transient receptor potential (TRP)-1 protein in liver and airway smooth muscle cells using immunoprecipitation and Western-blot analysis. Biochem J. 2002;364:641–648. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Godin N, Rousseau E. TRPC6 silencing in primary airway smooth muscle cells inhibits protein expression without affecting OAG-induced calcium entry. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;296:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9309-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ay B, Prakash YS, Pabelick CM, Sieck GC. Store-operated Ca2+ entry in porcine airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L909–L917. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00317.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosker C, Graziani A, Lukas M, Eder P, Zhu MX, Romanin C, Groschner K. Ca2+ signaling by TRPC3 involves Na+ entry and local coupling to the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13696–13704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prakash YS, Thompson MA, Vaa B, Matabdin I, Peterson TE, He T, Pabelick CM. Caveolins and intracellular calcium regulation in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L1118–L1126. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00136.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu XS, Xu YJ. Potassium channels in airway smooth muscle and airway hyperreactivity in asthma. Chin Med J (Engl) 2005;118:574–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coburn RF, Baron CB. Coupling mechanisms in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:L119–L133. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1990.258.4.L119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kannan MS, Prakash YS, Brenner T, Mickelson JR, Sieck GC. Role of ryanodine receptor channels in Ca2+ oscillations of porcine tracheal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L659–L664. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.4.L659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Worley JF, 3rd, Kotlikoff MI. Dihydropyridine-sensitive single calcium channels in airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:L468–L480. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1990.259.6.L468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ito Y, Takagi K, Tomita T. Relaxant actions of isoprenaline on guinea-pig isolated tracheal smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;116:2738–2742. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb17235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murray RK, Kotlikoff MI. Receptor-activated calcium influx in human airway smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 1991;435:123–144. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pabelick CM, Ay B, Prakash YS, Sieck GC. Effects of volatile anesthetics on store-operated Ca(2+) influx in airway smooth muscle. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:373–380. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200408000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Selvaraj S, Sun Y, Singh BB. TRPC channels and their implication in neurological diseases. CNS Neurol Disorder Drug Targets. 2010;9:94–104. doi: 10.2174/187152710790966650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Berninger B, Garcia DE, Inagaki N, Hahnel C, Lindholm D. BDNF and NT-3 induce intracellular Ca2+ elevation in hippocampal neurones. Neuroreport. 1993;4:1303–1306. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199309150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Canossa M, Griesbeck O, Berninger B, Campana G, Kolbeck R, Thoenen H. Neurotrophin release by neurotrophins: implications for activity-dependent neuronal plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13279–13286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang X, Berninger B, Poo M. Localized synaptic actions of neurotrophin-4. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4985–4992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-04985.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li YX, Xu Y, Ju D, Lester HA, Davidson N, Schuman EM. Expression of a dominant negative TrkB receptor, T1, reveals a requirement for presynaptic signaling in BDNF-induced synaptic potentiation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10884–10889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li HS, Xu XZ, Montell C. Activation of a TRPC3-dependent cation current through the neurotrophin BDNF. Neuron. 1999;24:261–273. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80838-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.