Abstract

Importance

Much of the enthusiasm for accountable care organizations is fueled by evidence that integrated delivery systems (IDSs) perform better on measures of quality and cost in the ambulatory care setting; however, the benefits of this model are less clear for complex hospital-based care.

Objective

To assess whether existing IDSs are associated with improved quality and lower costs for episodes of inpatient surgery.

Design, Setting, and Patients

We used national Medicare data (January 1, 2005, through November 30, 2007) to compare the quality and cost of inpatient surgery among patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting, hip replacement, back surgery, or colectomy in IDS-affiliated hospitals compared with those treated in a matched group of non–IDS-affiliated centers.

Main Outcome Measures

Operative mortality, postoperative complications, readmissions, and total and component surgical episode costs.

Results

Patients treated in IDS hospitals differed according to several characteristics, including race, admission acuity, and comorbidity. For each of the 4 procedures, adjusted rates for operative mortality, complications, and readmissions were similar for patients treated in IDS-affiliated compared with non–IDS-affiliated hospitals, with the exception that those treated in IDS-affiliated hospitals had fewer readmissions after colectomy (12.6% vs 13.5%, P=.03). Adjusted total episode payments for hip replacement were 4% lower in IDS-affiliated hospitals (P < .001), with this difference explained mainly by lower expenditures for postdischarge care. Episode payments differed by 1% or less for the remaining procedures.

Conclusions

The benefits of the IDSs observed for ambulatory care may not extend to inpatient surgery. Thus, improvements in the quality and cost-efficiency of hospital-based care may require adjuncts to current ACO programs.

Accountable care organizations (ACOs), a signature reform in the Affordable Care Act, are being developed and implemented across the United States.1 In many ways, the primary goal of ACOs is to encourage greater integration of local delivery systems and better coordination of care.2-4 In addition to their new requirements for shared governance and accountability, ACOs will accelerate such care integration through the introduction of financial incentives (eg, shared savings) that reward provider groups for collectively meeting specific quality and cost benchmarks.1 Previous research about the benefits of integrated delivery systems (IDSs) in ambulatory care suggests that ACOs are likely to improve efficiency in that clinical context.5,6 What is less clear, however, is whether benefits of the IDS model also accrue to hospital-based care, a major component of health care services in the United States with expenditures exceeding $800 bil-lion annually.7 Given the focus on collective accountability, shared electronic health records, and systems for coordination of care,8,9 IDSs may provide more efficient inpatient care through reductions in duplicative services, fewer readmissions, and/or more judicious use of postdischarge care. However, quality and cost for complex hospital-based care may depend less on care coordination and more on technical expertise and experience, attributes that are less synonymous with the IDS model.

Ultimately, the effect of ACOs on hospital-based care will be determined by future empirical studies that examine the comparative quality and cost of inpatient care provided by participants in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Innovation Pioneer program and other emerging ACOs. In the meantime, however, a better understanding of whether existing IDSs provide more efficient hospital-based care would help policymakers anticipate the likely effects of ACOs in this key clinical setting. Accordingly, we used national Medicare data to evaluate differences in the quality and cost of inpatient surgical care among patients treated in IDS-affiliated hospitals compared with those undergoing surgery in a matched group of non–IDS-affiliated centers.

METHODS

PARTICIPANTS AND DATABASES

This study was based on complete Medicare claims data for a cohort of patients undergoing selected inpatient operations from January 1, 2005, through November 30, 2007. Using methods described previously,10-12 we identified (from the MEDPAR file) patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), hip replacement, back surgery, and colectomy based on the presence of specific procedure codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (codes available from the authors on request). We linked the patient records to other CMS files with claims relevant to the surgical hospitalization, including the carrier (ie, physician), outpatient, home health, skilled nursing facility, long-stay hospital, and durable medical equipment files. The study cohorts included patients treated surgically from January 1, 2005, through November 30, 2007. To ensure complete outcome data, we did not include patients who had surgery in December 2007.

IDENTIFICATION OF HOSPITALS AFFILIATED WITH IDSs

We used the Integrated Healthcare Networks Profiling Solution database from IMS Health to identify IDSs in the United States.13,14 On a yearly basis, these data are used to generate a rating system that compares IDSs on their performance level and degree of integration. The overall rating system analyzes performance for 33 attributes in the following 8 domains: overall integration, integrated technology, hospital utilization, financial stability, services, access, contract capabilities, and physicians. Domain-specific scores are added to yield an overall score for the IDS; higher scores reflect greater degrees of self-reported integration.14 On the basis of the overall integration scores, IMS Health publishes an annual list of the top 100 IDSs nationally.14

Frequently, IDSs are associated with multiple hospitals. For this analysis, we decided a priori to identify the subset of hospitals that were affiliated with IDSs included in the 2007 list of the top 100 IDSs nationally and that also reported a formal relationship with one or more physician practices. This process yielded a sample of 374 hospitals affiliated with 92 IDSs from 36 states (range for number of hospitals associated with a parent IDS, 1-23) (eFigure; http://www.jamasurg.org). Because we excluded from analysis facilities that performed fewer than 30 of the procedures of interest during the study interval, the final hospital sample sizes for CABG, hip replacement, back surgery, and colectomy were 167 (affiliated with 86 IDSs), 307 (89 IDSs), 209 (87 IDSs), and 240 (87 IDSs), respectively. We refer to these hospitals throughout the article as IDS-affiliated hospitals.

IDENTIFICATION OF COMPARISON HOSPITALS

Next, we identified a comparison sample of hospitals that possessed structural characteristics similar to our sample of IDS-affiliated hospitals but that did not have an IDS affiliation in 2007. To do this, we used data from the American Hospital Association to implement a propensity score-matching approach that identified an equally sized sample of non–IDS-affiliated hospitals (for each procedure) that matched as closely as possible with hospitals in our IDS sample for case volume, bed size, Medicare discharges, and teaching hospital status. On the basis of this approach, the non–IDS-affiliated hospital sample sizes for CABG, hip replacement, back surgery, and colectomy were 167, 307, 209, and 240, respectively.

PRIMARY OUTCOMES

We defined 2 categories of outcomes for this analysis: quality and episode payments. Our measures of quality have been described previously and include operative mortality, postoperative complications, and readmissions.12 We defined operative mortality as death occurring within 30 days or before discharge from the index surgical hospitalization. Consistent with prior work,12,15 complications were ascertained using a subset of serious complications from the Complication Screening Project of Iezzoni et al.16,17

As described previously,10-12 we also measured total and component Medicare payments for the surgical episode. We defined surgical episodes as starting on the date of admission for the procedure of interest and continuing until 30 days after the date of hospital discharge.10 We divided the total payment data into 4 discrete categories: index hospitalization, readmissions, physician services, and postdischarge care.10

To adjust for intentional variations in Medicare payments (ie, differences in compensation based on regional wages, teaching medical trainees, and caring for underinsured patients, among other factors), payments were also price standardized using methods described previously.18

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

As a first step, we used ✗2 and t tests to compare characteristics of the hospitals and patients in our 2 samples. With patients as the unit of analysis, we then fit procedure-specific multivariable regression models to estimate associations between our quality and cost outcomes and treatment in an IDS-affiliated hospital. We implemented generalized estimating equations or random-effects models to account for clustering of patients within hospitals, and we adjusted the models for patient characteristics, including age, sex, race, admission acuity, comorbidity, and preoperative length of stay. In an effort to account for unmeasured differences in illness severity, we also adjusted for each patient's Medicare expenditures in the 6 months preceding surgery. Finally, we included in our models several measurable hospital characteristics, including bed size, Medicare discharges, teaching status, and procedure-specific case volumes.

From the cost models, we also calculated for each procedure the case mix–adjusted and price-standardized total and component episode payments for patients treated in IDS-affiliated compared with non–IDS-affiliated hospitals.

We performed all analyses using SAS computerized statistical software, (version 19; SAS Institute, Inc), at the .05 significance level. The University of Michigan Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences institutional review board determined that this study was exempt from its review.

RESULTS

The IDS-affiliated hospitals were slightly lower capacity for annual Medicare discharges (Table 1). The mean case volumes were evenly matched across hospitals, both overall (Table 1) and for the procedure-specific cohorts (data not shown).

Table 1.

Characteristics of IDS-Affiliated Hospitals Compared With Non–IDS-Affiliated Hospitalsa

| Characteristic | IDS-Affiliated Hospitals (n = 374) | Non–IDS-Affiliated Hospitals (n = 374) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital characteristic | |||

| Mean No. of total beds | 281 | 308 | .08 |

| Median No. of total beds | 209 | 276 | <.001 |

| Mean No. of annual Medicare discharges | 5725 | 6576 | .004 |

| Median No. of annual Medicare discharges | 4407 | 6003 | <.001 |

| Teaching hospitals, % | 17.17 | 17.38 | .94 |

| Median Medicare case volume, No. | |||

| CABG | 272 | 269 | .74 |

| Back surgery | 173 | 169 | .77 |

| Hip replacement | 125 | 168 | <.001 |

| Colectomy | 66 | 75 | .045 |

| Mean Medicare case volume, No. | |||

| CABG | 374 | 327 | .13 |

| Back surgery | 239 | 210 | .14 |

| Hip replacement | 182 | 192 | .39 |

| Colectomy | 82 | 83 | .82 |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; IDS, integrated delivery system.

The case volumes presented are limited to hospitals that performed at least 30 of the procedures of interest during the study interval.

Although the differences were generally small in magnitude and dependent on procedure, patients treated in IDS hospitals varied from those treated in non-IDS centers according to several characteristics, including race, admission acuity, and comorbidity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients Treated in IDS-Affiliated Hospital Compared With Non–IDS-Affiliated Hospitals, According to Surgical Procedure

| Characteristic | IDS-Affiliated Hospitals | Non–IDS-Affiliated Hospitals | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CABG | |||

| Patient, No. | 62 414 | 54 632 | |

| Age, mean, y | 74.8 | 74.6 | <.001 |

| Female, % | 33.0 | 32.9 | .77 |

| Black, % | 5.7 | 5.1 | <.001 |

| Admission acuity, % elective | 45.1 | 51.0 | <.001 |

| ≥2 Elixhauser comorbidities, % | 64.0 | 64.5 | .11 |

| Preoperative length of stay, mean, d | 3.2 | 3.3 | <.001 |

| Mean Medicare expenditures in 6 months before surgery, $ | 6500 | 6720 | <.001 |

| Hip replacement | |||

| Patient, No. | 55 867 | 58 994 | |

| Age, mean, y | 76.2 | 76.1 | .36 |

| Female, % | 63.2 | 63.5 | .23 |

| Black, % | 4.1 | 3.8 | .04 |

| Admission acuity, % elective | 92.6 | 94.5 | <.001 |

| ≥2 Elixhauser comorbidities, % | 53.6 | 52.2 | <.001 |

| Preoperative length of stay, mean, d | 1.1 | 1.1 | .45 |

| Mean Medicare expenditures in 6 months before surgery, $ | 5747 | 5908 | <.001 |

| Back surgery | |||

| Patients, No. | 49 934 | 43 943 | |

| Age, mean, y | 74.2 | 74.2 | .91 |

| Female, % | 58.3 | 57.7 | .04 |

| Black, % | 5.2 | 4.9 | .07 |

| Admission acuity, % elective | 82.8 | 85.4 | <.001 |

| ≥2 Elixhauser comorbidities, % | 53.7 | 51 6 | <.001 |

| Preoperative length of stay, mean, d | 1.6 | 1.6 | .47 |

| Mean Medicare expenditures in 6 months before surgery, $ | 8829 | 8847 | .76 |

| Colectomy | |||

| Patients, No. | 19 589 | 19 815 | |

| Age, mean, y | 78.4 | 78.3 | .13 |

| Female, % | 56.3 | 55.4 | .05 |

| Black, % | 8.2 | 8.5 | .21 |

| Admission acuity, % elective | 62.9 | 60.9 | <.001 |

| ≥2 Elixhauser comorbidities, % | 73.0 | 73.2 | .65 |

| Preoperative length of stay, mean, d | 2.8 | 3.0 | <.001 |

| Mean Medicare expenditures in 6 months before surgery, $ | 6416 | 6486 | .45 |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; IDS, integrated delivery system.

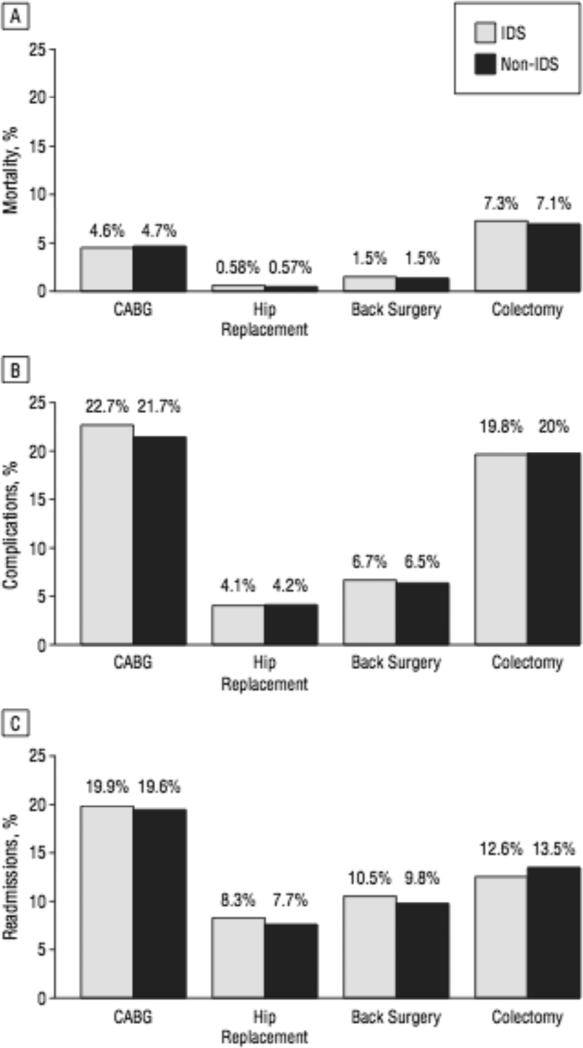

In terms of quality measures, unadjusted rates for the individual procedures ranged from 0.6% (hip replacement) to 7.3% (colectomy) for operative mortality, 4.2% (hip replacement) to 22.7% (CABG) for complications, and 8.3% (hip replacement) to 19.9% (CABG) for readmissions. Adjusted rates for measures of quality were generally similar for patients treated in IDS hospitals compared with non-IDS hospitals (Figure), with the exception that patients treated in IDS hospitals had a lower likelihood of readmission after colectomy (12.6% vs 13.5%, P = .03).

Figure.

Adjusted rates of operative mortality, postoperative complications, and hospital readmission after common inpatient operations according to hospital affiliation with an integrated delivery system (IDS). A, Operative mortality; B, postoperative complications; C, readmissions. The y-axis presents the adjusted percentage of patients with the outcome of interest. None of the differences between IDS-affiliated and non–IDS-affiliated hospitals are statistically significant, with the exception that patients treated in IDS-affiliated hospitals had a lower likelihood of readmission after colectomy (P = .03). CABG indicates coronary artery bypass graft.

After accounting also for differences in patient demographics and illness severity (ie, case mix), the price-standardized total and component episode payments for patients treated in IDS-affiliated hospitals were largely indistinguishable from those for non–IDS-affiliated facilities (Table 3). One exception is that total episode payments for hip replacement were $932 (4%) lower in IDS-affiliated hospitals (P < .001), with this difference explained almost entirely by lower expenditures for postdischarge care (Table 3). Total episode payments varied by 1% or less for the other 3 procedures, and these differences were not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Total and Component Medicare Payments for Surgical Episodes According to Hospital Affiliation With an IDSa

| Payment, $ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | IDS-Affiliated Hospitals | Non–IDS-Affiliated Hospitals | Difference |

| Total episode | |||

| CABG | 44 709 | 44 956 | –247 |

| Hip replacementb | 21 999 | 22 931 | –932 |

| Back surgery | 35 877 | 36 289 | –411 |

| Colectomy | 24 428 | 24 678 | –250 |

| Index hospitalization | |||

| CABG | 33 216 | 33 100 | 116 |

| Hip replacement | 12 413 | 12 478 | –65 |

| Back surgery | 22 222 | 22 050 | 172 |

| Colectomy | 17 757 | 17 616 | 140 |

| Readmissions | |||

| CABG | 2352 | 2288 | 63 |

| Hip replacement | 833 | 788 | 45 |

| Back surgery | 1572 | 1542 | 31 |

| Colectomy | 1216 | 1301 | –85 |

| Physician services | |||

| CABG | 5450 | 5416 | 34 |

| Hip replacement | 2423 | 2521 | –98 |

| Back surgery | 6192 | 6215 | –23 |

| Colectomy | 3181 | 3337 | –156 |

| Postdischarge care | |||

| CABG | 3874 | 4151 | –278 |

| Hip replacement | 6330 | 7145 | –815 |

| Back surgery | 5891 | 6482 | –592 |

| Colectomy | 2273 | 2423 | –150 |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; IDS, integrated delivery system.

Payments are price standardized and case mix adjusted. Index hospitalization is the first hospitalization in which the primary diagnosis would be treated by one of the specified procedures.

For total episode payments, the only significant difference between IDS-affiliated and non–IDS-affiliated hospitals was among patients undergoing hip replacement (P > .05).

COMMENT

Current evidence suggests that IDSs provide patients with higher quality ambulatory and preventive care services at a lower overall cost to Medicare and other payers.5,6,19 What has been less clear, however, is whether this care delivery model also yields higher-quality and/or lower-cost hospital-based care, which accounts for almost half of the total Medicare spending. Given that the financial incentives and structural requirements of ACOs encourage previously unaligned hospitals and physicians to evolve toward an IDS, a better understanding of this issue would be helpful to policymakers as they anticipate the likely effects of these new care systems on complex inpatient care.

We examined this question by comparing quality and cost outcomes among patients undergoing common inpatient operations in hospitals affiliated or not affiliated with IDSs. Quality of care—as measured by operative mortality, postoperative complications, and readmissions—was generally similar for patients treated in IDS and non-IDS hospitals. Total and component episode costs for patients treated in IDS-affiliated hospitals were also largely indistinguishable from those for patients undergoing surgery in non–IDS-affiliated facilities. The one exception was hip replacement, where total payments for patients treated in IDS-affiliated hospitals were approximately $1000 lower per episode than for patients undergoing the same procedures in comparison hospitals. A major driver of this overall payment difference for hip replacements was smaller outlays for postdischarge care among patients treated in IDS hospitals.

There are several potential reasons why the benefits observed with IDSs in the ambulatory setting may not translate to complex inpatient surgical care. In particular, the advantages of IDSs for chronic disease care may stem in large part from the availability of shared infra-structure and information systems that facilitate longitudinal care coordination.8,9 The main drivers of cost and quality for hospital-based surgical specialty care may be different and are likely to include large case volumes, the availability of highly specialized physicians, and the necessary hospital-based resources to facilitate early identification and management of postoperative complications.15,20-22 In this scenario, the benefits of IDSs observed for ambulatory and preventive care may be less likely to extend to patients receiving complex inpatient surgery.

Our study has several limitations. First, there is no standardized definition for an IDS, and there may be significant variability among the IDSs in this study for organizational structure, degree of financial and clinical integration, and the continuum of services provided. We could not measure and adjust for all of these important contextual factors. Furthermore, the characteristics and outcomes for IDSs in 2007 may be different than in 2012 (because many of these networks or systems now evolve into ACOs). Unlike existing IDSs, moreover, emerging ACOs include unique financial incentives aimed at stimulating innovations that improve quality and lower costs. As such, a full understanding of the effect of this model on inpatient surgical care will ultimately require a comparative study of hospitals participating or not participating in the Pioneer or Medicare Shaved Savings ACO programs.

Second, our analyses include only a sample of hospitals; it is possible that our findings do not generalize to the entire population of IDS-affiliated hospitals in the United States. Nevertheless, we analyzed a large number of hospitals affiliated with prominent IDSs from across the United States and, as such, our results provide useful insight regarding potential benefits associated with this organizational structure for patients in need of complex, hospital-based care.

Third, because our study was based on administrative data, we also cannot exclude the possibility that our findings are attributable to residual (ie, unmeasured) differences in illness severity across patients treated in IDS-affiliated vs non–IDS-affiliated hospitals. To minimize this risk, we applied several restrictions aimed at making our procedure cohorts as homogeneous as possible, while also adjusting for several measurable patient characteristics, including comorbidities and expenditures in the 6 months before surgery. An additional limitation is our exclusion of beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare managed care plans. To the extent that managed care enrollment is not distributed randomly across IDS-affiliated vs non–IDS-affiliated hospitals, this exclusion could bias our principal findings.

These limitations notwithstanding, our findings have implications for CMS, policymakers, hospitals, and other stakeholders involved in developing and evaluating ACO programs. In reality, it seems somewhat unlikely that reforms aimed at stimulating improvements through greater care coordination and integration will reduce mortality or complications after major inpatient surgery. In contrast to patients with chronic medical conditions, moreover, readmissions after inpatient surgery often reflect the occurrence of complications rather than breakdowns in care coordination or transitions.

Thus, for inpatient surgery, improvements in both quality and cost-efficiency are likely to require adjuncts to the payment reforms and shared accountability at the heart of current ACO programs. Given their success to date, payers, policymakers, hospitals, and ACO leadership should consider supporting clinician participation in specialty-based regional collaborative improvement programs as a complementary strategy for reducing morbidity, mortality, and expenditures associated with complex inpatient surgery.23,24

At the same time, however, empiric confirmation that episode costs for hip replacement are lower at IDS-affiliated hospitals provides at least some evidence that accelerating care integration via ACO formation could lead to reduced costs, even with inpatient surgery. Moreover, because outlays for postdischarge care explained most of the difference in hip replacement payments for IDS-affiliated hospitals compared with non–IDS-affiliated hospitals, our results are also informative for CMS and other payers as they move toward implementation of bundled payments around episodes of inpatient surgery. Namely, it seems that payers will have incentives to include expenditures for home health, rehabilitative, nursing, and other services provided after hospital discharge in the payment bundle for inpatient operations, particularly for orthopedic procedures. Finally, although these data provide useful preliminary insight regarding the relationship between delivery system integration and surgical costs and quality, they also highlight the need to better understand specific attributes of IDSs (eg, governance, physician leadership, and clinical and/or economic integration) that correlate with greater quality and cost-efficiency, as well as the technical processes of care used by high-performing surgeons and hospitals. Identification of these factors would not only allow them to be rewarded by payers and policymakers but could also facilitate exportation of key determinants of high-quality and cost-efficient inpatient care to emerging ACOs.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grants K08 HS018346-01A1 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Dr Miller), P01 AG19783-01 from the National Institute of Aging (Dr Birkmeyer), and the Astellas Rising Star in Urology Research Award from the American Urological Association Foundation (Dr Miller). Role of the Sponsor: ArborMetrix, Inc, had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: Dr Birkmeyer has an equity interest in ArborMetrix, Inc, a company that provides software and analytics for assessing hospital quality and efficiency. Dr Miller serves as a paid consultant for UnitedHealth Care (all payments have been donated to the resident education fund in the Department of Urology at University of Michigan).

REFERENCES

- 1.Berwick DM. Making good on ACOs’ promise—the final rule for the Medicare shared savings program. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(19):1753–1756. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1111671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shortell SM, Casalino LP, Fisher ES. How the center for Medicare and Medicaid innovation should test accountable care organizations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(7):1293–1298. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee TH, Casalino LP, Fisher ES, Wilensky GR. Creating accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(15):e23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1009040. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1009040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Safran DG. Building the path to accountable care. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):2445–2447. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1112442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehrotra A, Epstein AM, Rosenthal MB. Do integrated medical groups provide higher-quality medical care than individual practice associations? Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(11):826–833. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-11-200612050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weeks WB, Gottlieb DJ, Nyweide DE, et al. Higher health care quality and bigger savings found at large multispecialty medical groups. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(5):991–997. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [September 20, 2012];National Health Expenditures Data: Selected Calendar Years. 1960-2010 http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics -Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData /Downloads/tables.pdf.

- 8.Enthoven AC. Integrated delivery systems: the cure for fragmentation. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(10)(suppl):S284–S290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shortell SM, McCurdy RK. Integrated health systems. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2010;153:369–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller DC, Gust C, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer N, Skinner J, Birkmeyer JD. Largevaria- tions in Medicare payments for surgery highlight savings potential from bundled payment programs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(11):2107–2115. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birkmeyer JD, Gust C, Baser O, Dimick JB, Sutherland JM, Skinner JS. Medi- care payments for common inpatient procedures: implications for episode- based payment bundling. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(6 pt 1):1783–1795. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birkmeyer JD, Gust C, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer NJO, Skinner JS. Hospital quality and the cost of inpatient surgery in the United States. Ann Surg. 2012;255(1):1–5. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182402c17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. [August 30, 2012];Health IMS Top-Line Market Data. http://www.imshealth.com/portal/site/ims.

- 14. [August 30, 2012];Health IMS IMS IHN Rating System Description and Methodology. http://www.imshealth.com/ims/Global/Content/Corporate/Press%20Room/Top-Line %20Market%20Data%20&%20Trends/SDI%20Reports/2012_IHN_Rating _Methodology_.pdf.

- 15.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Complications, failure to rescue, and mortality with major inpatient surgery in Medicare patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250(6):1029–1034. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e3181bef697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iezzoni LI, Daley J, Heeren T, et al. Using administrative data to screen hospitals for high complication rates. Inquiry. 1994;31(1):40–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iezzoni LI, Daley J, Heeren T, et al. Identifying complications of care using administrative data. Med Care. 1994;32(7):700–715. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199407000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottlieb DJ, Zhou W, Song Y, Andrews KG, Skinner JS, Sutherland JM. Prices don't drive regional Medicare spending variations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(3):537–543. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sterns JB. Quality, efficiency, and organizational structure. J Health Care Finance. 2007;34(1):100–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1368–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0903048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(15):1128–1137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(22):2128–2137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1010705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birkmeyer NJ, Share D, Baser O, et al. Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Preoperative placement of inferior vena cava filters and outcomes after gastric bypass surgery. Ann Surg. 2010;252(2):313–318. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e61e4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Share DA, Campbell DA, Birkmeyer N, et al. How a regional collaborative of hospitals and physicians in Michigan cut costs and improved the quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(4):636–645. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]