Abstract

The reaction of an aminopolycarboxylate ligand, aspartic-N-monoacetic acid (ASMA), with [Re(CO)3(H2O)3]+ was examined. The tridentate coordination of ASMA to this ReI tricarbonyl precursor yielded fac-Re(CO)3(ASMA) as a mixture of diastereomers. The chemistry is analogous to that of the TcI tricarbonyl complex, which yields fac-99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) under similar conditions. The formation, structure, and isomerization of fac-Re(CO)3(ASMA) products were characterized by HPLC, 1H NMR spectroscopy, and X-ray crystallography. The two major fac-Re(CO)3(ASMA) diastereomeric products each have a linear ONO coordination mode with two adjacent five-membered chelate rings, but they differ in the endo or exo orientation of the uncoordinated acetate group, in agreement with expectations based on previous studies. Conditions have been identified for the expedient isomerization of fac-Re(CO)3(ASMA) to a mixture consisting primarily of one major product. Because different isomeric species typically have different pharmacokinetic characteristics, these conditions may provide for the practical isolation of a single 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) species, thus allowing the isolation of the isomer that has optimal imaging and pharmacokinetic characteristics. This information will aid in the design of future 99mTc radiopharmaceuticals.

Keywords: Rhenium, Aminopolycarboxylate ligands, Ligand design, Isomer resolution, Imaging agents

Introduction

Rhenium (Re) complexes are currently being investigated for use as luminescent probes,[1] CNS agents,[2] and chemotherapy agents.[3] As a congener of Tc, Re complexes are also commonly employed as structural analogues for 99mTc radiotracers.[4] Re analogues allow for elucidation of 99mTc radiopharmaceuticals, which are otherwise difficult to characterize owing to the short half-life of 99mTc (t1/2 = 6 h) and the tracer level conditions (no-carrier-added) of radiopharmaceutical preparations. Methods for the preparation of Re complexes have been developed to mirror standard radiolabeling conditions for various 99mTc complexes, including routes to 99mTcV-oxo,[5] 99mTcIII-trioxo,[6] and 99mTcI-tricarbonyl complexes.[7] The recently improved preparation of ReI-tricarbonyl complexes via the Re precursor, [Re(CO)3(H2O)3]OTf,[8] has been especially helpful in characterizations of several new 99mTc(CO)3+ renal tracers developed as potential replacements for the most widely used 99mTc renal tracer, 99mTcO-mercaptoacetyltriglycine (99mTc-MAG3).[8–9]

We recently designed, prepared, and evaluated the efficacy of fac-99mTc(CO)3(aspartic-N-monoacetic acid), abbreviated as fac-99mTc(CO)3(ASMA), as a potential new renal tracer.[10] Note that we have adopted the following naming conventions which distinguish the chirality of the ligand: "Re(CO)3(l-ASMA)" refers to a complex with l-ASMA, whereas "Re(CO)3(ASMA)" refers to a complex with any preparation of ASMA ligand. In order to simplify nomenclature, we have omitted the "fac-" prefix and any designation of the ligand protonation state (such as ASMAH3, or ASMAH) for the remainder of this report.

We determined that the pharmacokinetic properties of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) in normal rats are comparable to those of 131I-ortho-iodohippurate (131I-OIH), the radioactive standard for measurements of effective renal plasma flow, and even superior to 131I-OIH in rats with simulated renal failure.[9e, 10] Thorough structural characterization of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) is necessary because the radiotracer can exist as any of several distinct isomers. Structural ambiguity arises from several factors including the chirality of the ASMA ligand and the fact that ASMA has more donor groups (4 groups) than available coordination sites on the 99mTc(CO)3+ core (3 sites). In the absence of structural data, we relied on trends in ligand chelation mode established in studies of well-characterized ReI-tricarbonyl complexes with aminopolycarboxylates and other ligands in order to predict characteristics of 99mTcI(CO)3(ASMA) such as the chelate ring size, the linear or tripodal coordination of ASMA, and the likely orientation of uncoordinated groups.[8–9, 11]

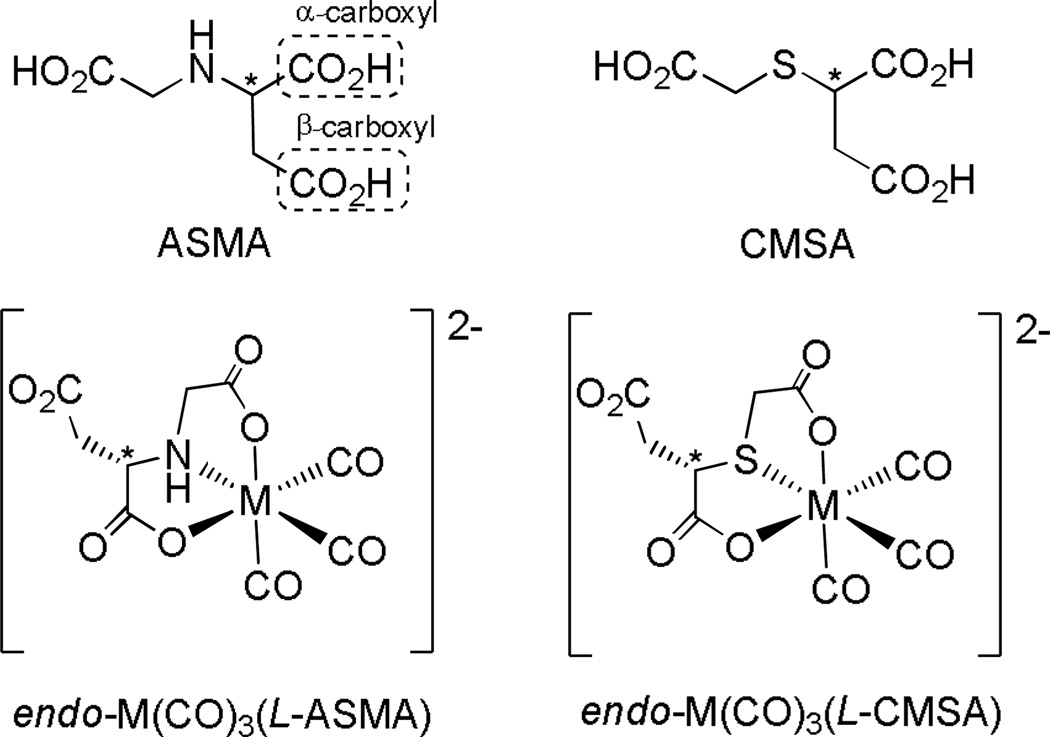

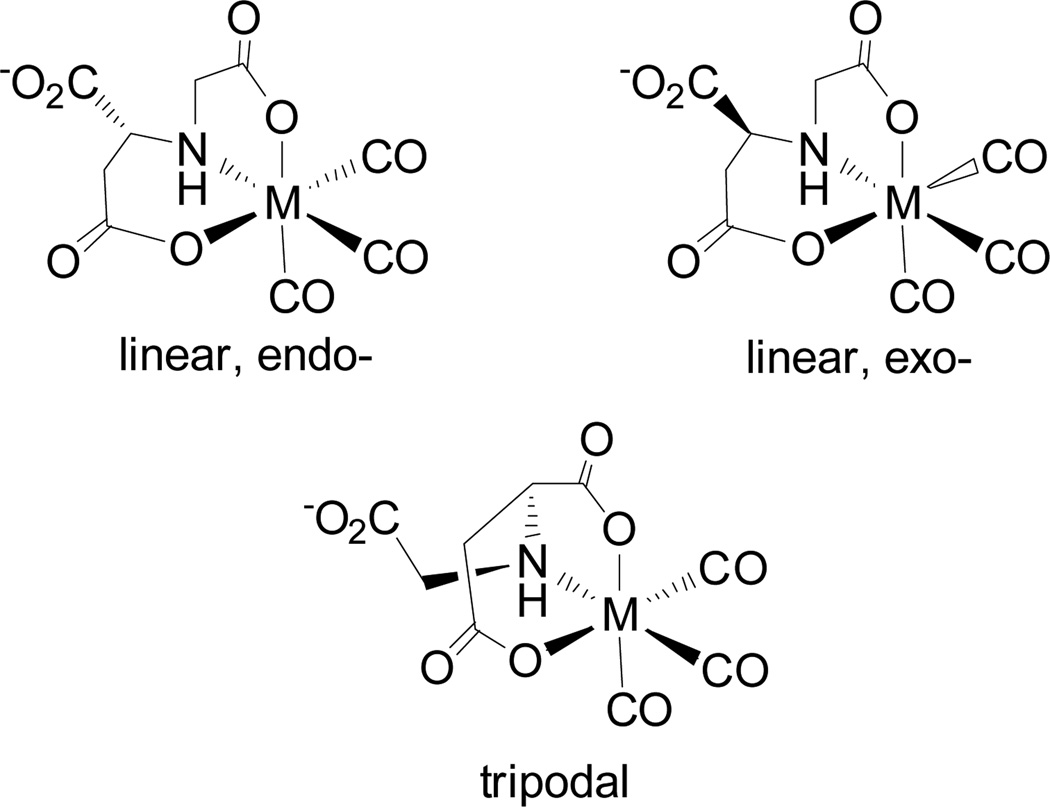

Particularly helpful for predicting the major products of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) was the strikingly similar example, 99mTc(CO)3(N-carboxymethylmercaptosuccinic acid) (99mTc(CO)3(CMSA), Figure 1).[9d] Extensive characterization of its Re analogue, Re(CO)3(CMSA), showed that M(CO)3(CMSA) (M = 99mTc, Re) exists as a mixture of diastereomers. In each isomer, CMSA coordinates as a tridentate ligand, forming two adjacent five-membered chelate rings in a facial OSO arrangement. The Re(CO)3(CMSA) diastereomers differ only in the position and orientation of the uncoordinated acetate group, designated endo- when projecting toward the face defined by the carbonyl ligands, as in Figure 1, and exo- when projecting away from the tricarbonyl face. Because ASMA and CMSA differ only at the central heteroatom (N vs. S, respectively), we expected that M(CO)3(ASMA) would also exist as a mixture of diastereomers. In order to confirm this prediction, we have prepared and characterized Re(CO)3(ASMA) isomers.

Figure 1.

Tridentate ligand chelation in M(CO)3(ASMA) (M = 99mTc, Re) is expected to be similar to that in M(CO)3(CMSA), yielding a diastereomeric mixture of products having an OXO (X = S, N) coordination mode with two adjacent five-membered chelate rings. Each product is expected to be dianionic near physiological pH. Only one diastereomer of each complex is shown for simplicity.

Results and Discussion

The synthesis of ASMA as an enantiomerically pure sample (l-ASMA, 1, or d-ASMA, 3) and as a racemic mixture of d- and l- isomers (rac-ASMA, 5) has been described previously.[12] Generally, 1 and 3 were synthesized via nucleophilic substitution of bromoacetic acid by using l- or d-aspartic acid as the nucleophile. The monosubstituted product was separated in good yield from unchanged starting materials, disubstituted by-products, and excess salt by cation exchange chromatography. Synthesis of 5 in acceptable yield proceeded via Michael addition of glycine to maleic acid, which eliminated the possibility of disubstituted products. An excess of maleic acid ensured that the amino acid starting material was consumed.

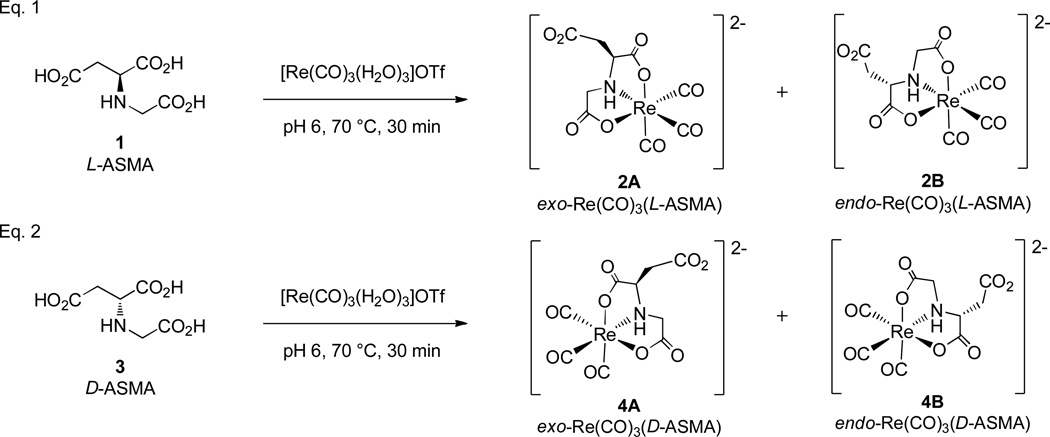

Re(CO)3(ASMA) complexes were prepared by combining 1, 3, or 5 with a slight excess of the [Re(CO)3(H2O)3]+ precursor and maintaining a pH of 6 by using sodium hydroxide to replicate conditions for 99mTc labeling (Figure 2). Tetramethylammonium hydroxide was also used in the synthesis of Re(CO)3(rac-ASMA) in attempts to facilitate crystallization of the product from aqueous solution (see below). Reaction progress was monitored by HPLC at both 20 °C and 70 °C. Coordination of 1, 3 or 5 to [Re(CO)3(H2O)3]+ proceeded in an identical manner, giving mixtures that differed only as expected owing to the optical activity of the ligand.

Figure 2.

Summary of coordination reactions of l-ASMA (Eq. 1) and d-ASMA (Eq. 2) with the ReI tricarbonyl precursor. Each ligand gives rise to a diastereomeric mixture of products. The racemic mixture (rac-ASMA, 5) gives rise to four products (two diastereomeric pairs of enantiomers 2A – 4A and 2B – 4B, respectively). Note that the enantiomers arise in this way because the ASMA ligand is a linear ligand with one end different from the other end. Therefore, for a facial coordination mode, isomerization between an endo- and an exo-isomer of a M(CO)3(ASMA) complex for a given ASMA isomer (l or d) by necessity changes the chirality at the metal center, as illustrated above.

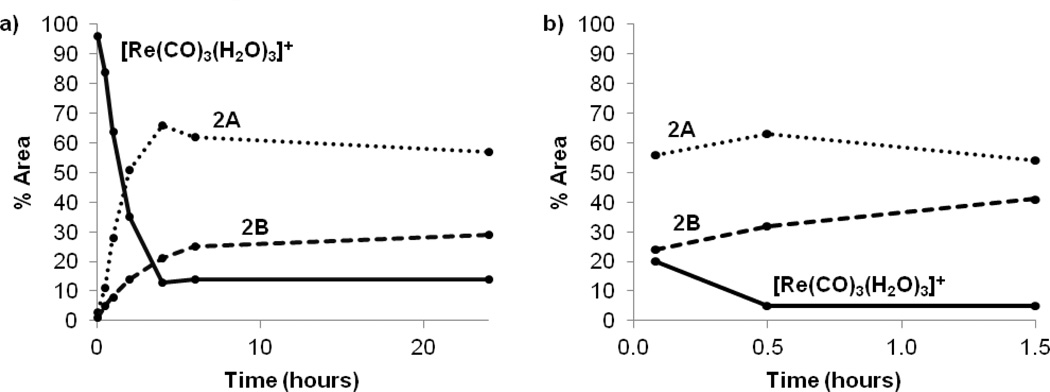

At room temperature and pH 6, the coordination reaction progressed steadily toward completion over 4 h, whereas heating at 70 °C pushed the reaction to completion within 30 min (Figure 3). According to HPLC, treatment of [Re(CO)3(H2O)3]+ with 1 yields two major products, 2A and 2B, named by their order of elution (retention times: 16.3 min and 17.6 min, respectively). Thorough analysis of the characterization has confirmed that these products are the exo- (2A) and endo- (2B) diastereomers of Re(CO)3(ASMA) shown in Figure 2, Eq. 1. Intermediates observed during the reaction with relatively short retention times (4–8 min) are likely monodentate or bidentate complexes (see Supporting Information). Two minor products with a retention time of ~14 min persist at room temperature, but quickly and completely convert to the major products 2A and 2B after heating for 1 h. Although these intermediates could not be isolated, we believe they are Re(CO)3(ASMA) isomers having one five- and one six-membered chelate ring. Previous studies demonstrate that six-membered NO chelate rings are less energetically favorable and form more slowly than five-membered chelate rings.[13] Hence we expect that complexes with both a five-membered and a six-membered NO chelate ring will be present only in small amounts and will readily convert to products with two five-membered chelate rings, as is observed.

Figure 3.

The progression of the major species formed and present in the reaction mixture (pH 6) of l-ASMA, 1, with a slight excess of [Re(CO)3(H2O)3]+ as assessed by the relative % area of HPLC traces. Increasing the reaction temperature from 20 °C (a) to 70 °C (b) significantly accelerated the reaction.

Identical HPLC chromatograms were observed when using either 3 or 5 as the ligand. However, for Re(CO)3(rac-ASMA), each peak now represents an enantiomeric mixture of isomers, leading to the presence of four major products in the final reaction mixture: Re(CO)3(l-ASMA) diastereomers 2A, 2B and their Re(CO)3(d-ASMA) enantiomers 4A and 4B (Figure 2, Eq. 2).

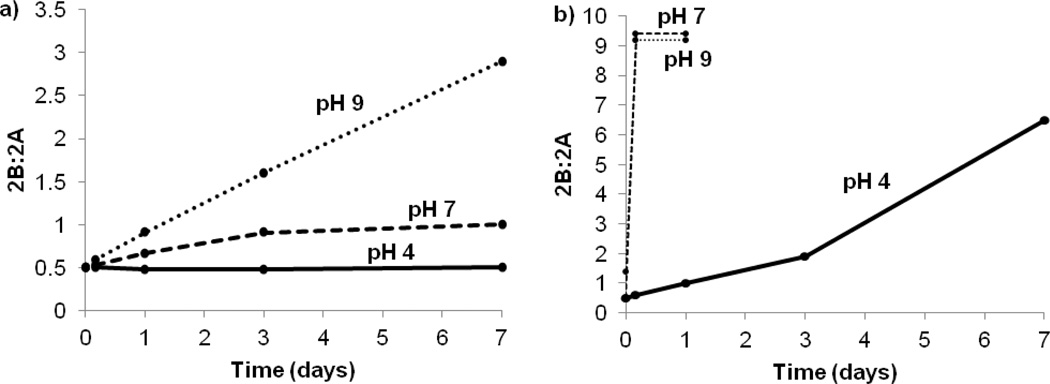

Figure 3a shows that over the course of 1 d at 20 °C and pH 6, the product ratio gradually shifts toward the endo isomer, 2B. The major products were initially formed in a ratio of 3:1 (2A:2B), but after 1 d at 20 °C the ratio had shifted to 2:1, indicating that 2A slowly isomerizes to 2B at these conditions. Heating the reaction mixture accelerates both the formation and isomerization reactions, as evidenced by a roughly 2:1 ratio of 2A:2B obtained after just 5 min at 70 °C (Figure 3b). HPLC chromatograms before and after isomerization were compared to the sample's 1H NMR spectra and showed no difference in product ratios, indicating that the ratio of isomers is not significantly affected by the HPLC method. To examine this isomerization further, a small aliquot of the product mixture (after 24 h at 20 °C, pH 6, 2:1 ratio of 2A:2B) was divided into six fractions. The temperature and pH of each sample was varied, and the conversion of 2A to 2B was followed by HPLC (Figure 4). For conditions under which the isomerization reached equilibrium quickly (70 °C, pH ≥ 7), the final ratio of 2A:2B was ~1:9. The robustness of 2A and 2B was not examined in particular in this study, although the complexes were chemically stable over periods of up to 7 d in the various conditions used in the isomerization study. HPLC analysis of the metabolites of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) in our parallel study[9e] shows that the complex is long lived in biological systems.

Figure 4.

The initial reaction for 1 d at 20 °C and pH 6 yielded a mixture of two Re(CO)3(l-ASMA) isomers, 2A (exo) and 2B (endo). The product ratio of the crude reaction mixture was studied by monitoring the % area from the HPLC trace for up to 7 d at 20 °C (a) and 70 °C (b) for pH 4, 7 and 9.

From Figure 4, it is clear that both heat and pH have a distinct effect on the isomerization of the product mixture. Without the benefit of heat or elevated pH (20 °C, pH 4), the initial product ratio of 2:1 is relatively constant. However, raising the pH to 9 at 20 °C accelerates the isomerization only slightly. Similarly, heating in acidic conditions (70 °C, pH 4) is not practical for rapid isomerization, and the products approach equilibrium only after 7 d. Thus, to promote expedient isomerization to the thermodynamic product, 2B, heating in neutral or slightly basic conditions is required (70 °C, pH ≥ 7). Although a thorough mechanistic study of this multi-step isomerization process is beyond the scope of this project, the acceleration of the reaction as pH increases strongly indicates that the initial step is deprotonation of the NH group by hydroxide to generate a small equilibrium amount of deprotonated complex. We hypothesize that the strongly donating N-donor thereby created will favor formation of a five-coordinate, short-lived intermediate yielding two closely related intermediates with either one of the two carboxyl groups dissociated. Collapse of either intermediate to regenerate the six-coordinate complex would lead to either the endo or exo isomer, depending on the direction in which the carboxyl moves to close the chelate ring.

Identifying the kinetic isomer (2A) and the thermodynamic isomer (2B) enables the assignment of these products to a specific diastereomer. The most energetically favorable arrangement (thermodynamic isomer 2B) will likely have the bulky dangling –CH2CO2− group facing away (endo) from the crowded chelate rings formed by the tridentate ASMA ligand, (Figure 5a). Similarly, the dangling carboxylate group (at pH 6) will be negatively charged and electrostatically repelled from the negatively charged inner coordination sphere center, making the endo- isomer more thermodynamically favorable. Because the thermodynamically favored product is likely to be the endo- isomer and because this isomer should be even more favored at high pH, we can make an initial structural assignment of 2B as endo-Re(CO)3(ASMA). Comparisons to the 1H NMR spectrum and the crystal structure of Re(CO)3(CMSA) support this assignment and consequently, the assignment of 2A (and 4A) as exo-Re(CO)3(ASMA).

Figure 5.

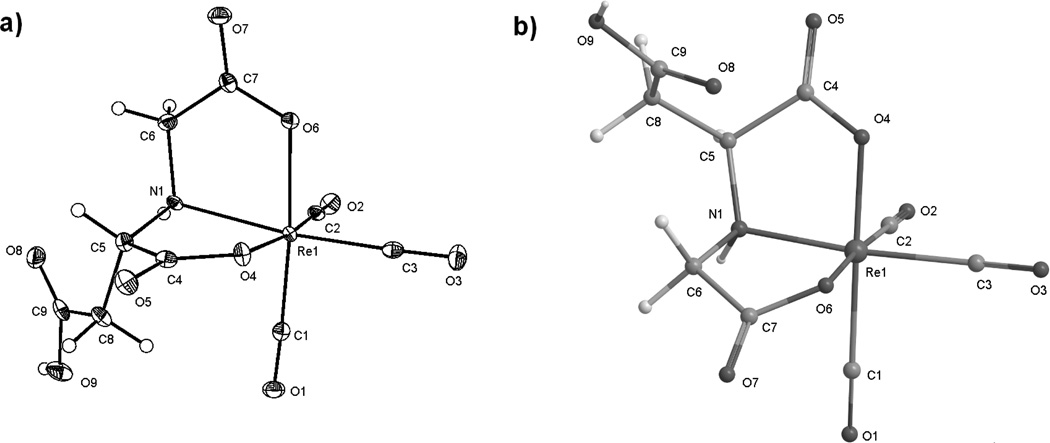

(a) ORTEP representation of one enantiomer (from l-ASMA) of the anion of K[endo-Re(CO)3(rac-ASMA)], 2B. Hydrogen atoms are shown in their calculated positions. The K+ cation is omitted for clarity. (b) A model of exo-Re(CO)3(l-ASMA) (2A) calculated using the MM2 force field[18] to illustrate the exo orientation of the dangling acetate group.

Crystallization of K[endo-Re(CO)3(rac-ASMA)] was achieved from a concentrated aqueous pH 2 solution of the equilibrated product. Slow evaporation of this sample yielded small, colorless crystals as a mixture of enantiomers 2B and 4B, with the uncoordinated carboxyl group protonated (Figure 5a). Attempts under similar conditions and at pH 6 to obtain crystals with a more hydrophobic counterion, NMe4[endo-Re(CO)3(rac-ASMA)], or the exo- enantiomers, NMe4[exo-Re(CO)3(rac-ASMA)] or K[exo-Re(CO)3(rac-ASMA)] were unsuccessful. To confirm that the crystals obtained corresponded to the thermodynamic isomer, a small crystal was dissolved and analyzed by HPLC. The only major peak corresponded to 2B and this peak contained >95% of the trace area. X-ray structural analysis shows that the enantiomers 2B and 4B (2B presented in Figure 5a) are indeed the endo isomer, K[endo-Re(CO)3(rac-ASMA)], as predicted from results for the thermodynamic product of Re(CO)3(CMSA).[9a] In the pseudo-octahedral complex, the coordinated tridentate ASMA ligand is bound in a facial ONO arrangement, giving rise to two adjacent five-membered NO chelate rings. The dangling protonated carboxyl group is facing away from the triangular ONO face as expected for the endo isomer. Bond distances between donor groups and the metal core (Re1–O4, Re1–O6, Re1–N1) are consistent with previous examples for carboxyl and amino donor groups (Table 1).[8, 14] Deviations from the expected geometry occur systematically between analogous bond angles of NMe4[endo-Re(CO)3(CMSA)] and those of other ReI-tricarbonyl complexes which share a similar coordination mode.[9c, 9d] The crystal structure confirms our assignment of thermodynamic isomers 2B and 4B as endo-Re(CO)3(ASMA). Additional crystallographic data for both complexes can be found at http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk (CCDC 884591).

Table 1.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for ReI tricarbonyl complexes with ASMA and CMSA.a

| K[endo-Re(CO)3(rac-ASMA)] | NMe4[endo-Re(CO)3(CMSA)][9d] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Distances | |||

| Re1-C1 | 1.889(4) | Re1-C3 | 1.897(4) |

| Re1-C2 | 1.906(4) | Re1-C1 | 1.913(4) |

| Re1-C3 | 1.914(4) | Re1-C2 | 1.927(4) |

| Re1-O4 | 2.135(2) | Re1-O6 | 2.127(2) |

| Re1-N1 | 2.201(3) | Re1-S1 | 2.452(1) |

| Re1-O6 | 2.138(2) | Re1-O4 | 2.164(2) |

| C7-C9b | 5.466 | C4-C9b | 5.824 |

| C4-C9b | 3.842 | C6-C9b | 3.005 |

| Angles | |||

| C1-Re1-N1 | 98.43(13) | C3-Re1-S1 | 95.86(11) |

| C1-Re1-C2 | 88.20(15) | C3-Re1-C1 | 89.23(14) |

| C1-Re1-C3 | 90.03(15) | C3-Re1-C2 | 88.30(15) |

| C1-Re1-O4 | 93.91(13) | C3-Re1-O6 | 95.92(12) |

| C2-Re1-N1 | 97.62(13) | C1-Re1-S1 | 94.89(12) |

| C2-Re1-O6 | 96.54(12) | C1-Re1-O4 | 90.78(11) |

| C2-Re1-C3 | 88.75(15) | C1-Re1-C2 | 91.17(16) |

| C3-Re1-O6 | 93.58(12) | C2-Re1-O4 | 95.92(12) |

| C3-Re1-O4 | 97.89(12) | C2-Re1-O6 | 93.33(13) |

| O6-Re1-N1 | 75.50((10) | O4-Re1-S1 | 79.94(6) |

| O6-Re1-N1 | 77.51(10) | O6-Re1-S1 | 80.29(7) |

| O4-Re1-O6 | 80.97(10) | O4-Re1-O6 | 83.76(8) |

| C2-Re1-O4 | 173.02(12) | C1-Re1-O6 | 173.25(12) |

| C1-Re1-O6 | 174.09(12) | C3-Re1-O4 | 175.78(13) |

| C3-Re1-N1 | 169.54(12) | C2-Re1-S1 | 172.69(12) |

Although the atom labels of each complex are inconsistent (labeled according to the appropriate CCDC file), each row lists an analogous length or angle.

Nonbonded distances between carboxyl group carbons.

The explicit characterization of 2B supports our assignment of 2A based on isomerization between the two products. However, the structure of 2A remains somewhat ambiguous because in addition to the expected exo-Re(CO)3(ASMA) product (Figure 5b), isomers with the β-carboxyl group (as labeled in Figure 1) coordinated to the metal core are possible (Figure 6). In a tripodal coordination mode, the ligand will form three chelate rings (one five-, one six-, and one seven-membered ring) with the metal core; such an arrangement has been shown to be unfavorable compared to that of 2B.[11a] Potential isomers with ASMA bound linearly through the β-carboxyl will form two adjacent chelate rings (one five- and one six-membered ring) which, although more likely to form than tripodal isomers, are less stable and form more slowly than 2A because of its six-membered chelate ring. Therefore, it is very unlikely that isomers with a coordinated β-carboxyl will contribute as major products to the reaction mixture of Re(CO)3(ASMA). However, as noted earlier, the isomers forming adjacent five- and six-membered chelate rings are likely the minor products that readily convert to 2A and 2B, as observed by HPLC.

Figure 6.

Conceivable isomers of Re(CO)3(ASMA) with the β-carboxyl group coordinated to the metal core. Enantiomers of the isomers shown would also exist, but are not pictured. For clarity, the complexes are shown without formal charges or counterions. Linearly coordinated isomers contain adjacent five- and six-membered chelate rings, whereas tripodal isomers contain a seven-membered ring.

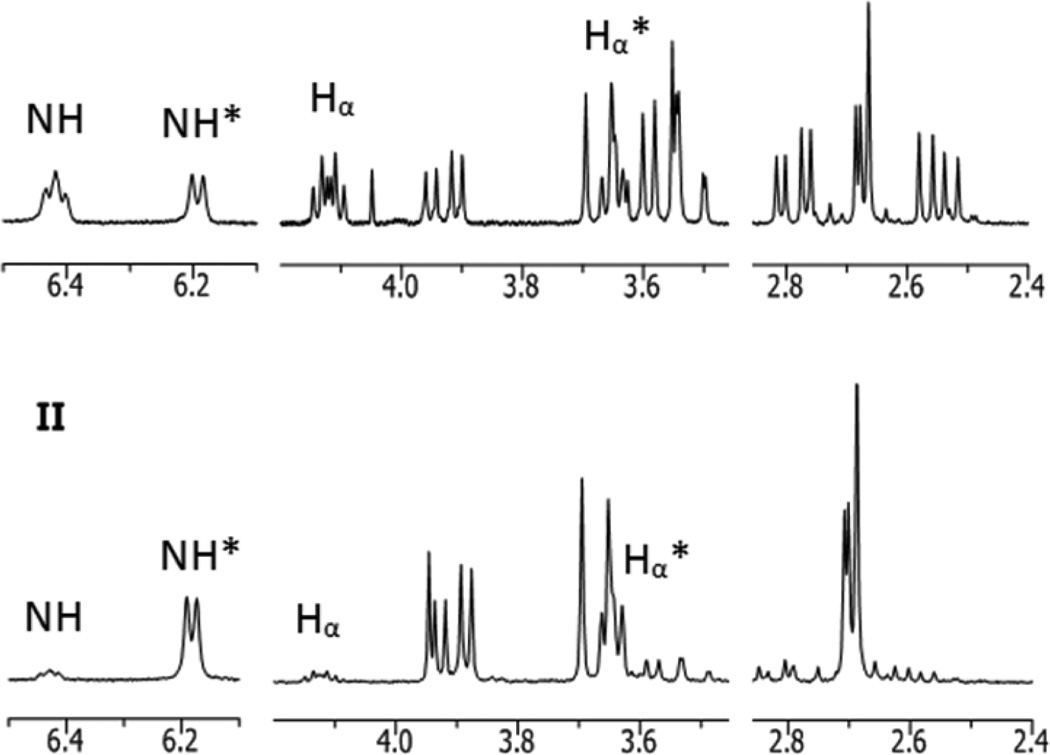

Further confirmation of the structure of 2A is possible through 1H NMR analysis. When both major products 2A and 2B are present in nearly equal amounts, the 1H NMR spectrum is difficult to interpret owing to the similarity in peak intensity and some overlap in peaks from the two sets (Figure 7, I). In the equilibrated sample (as detailed above), two sets of signals in a 1:9 ratio (2A:2B) are easily distinguishable (Figure 7, II). Each resonance was assigned to the appropriate diastereomer by comparing the two spectra, as shown in Figure 7. Expected signals for Re(CO)3(ASMA) isomers are observed in each spectrum, including an amino proton (NH), Hα, two protons from the coordinated N-carboxymethyl group (exo- and endo-HCOORD) and two Hβ protons from the uncoordinated acetate group, none of which are magnetically equivalent (Table 2). Each signal shows a splitting pattern that is consistent with the predicted coordination mode.

Figure 7.

1H NMR spectra (D2O, 20 °C, pH 6) of Re(CO)3(l-ASMA) maintained at 20 °C (I) and after heating at 70 °C for 3 d (II) are shown (detailed in Table 2). The signals from exo-Re(CO)3(l-ASMA) (2A) and endo-Re(CO)3(l-ASMA) (2B) can be deconvoluted by comparing the two spectra. Selected signals from 2A (I) and 2B (II, marked with an *) are labeled to highlight significant differences.

Table 2.

1H NMR data (D2O, pH 6) for 2A (exo) and 2B (endo) isomers of the [Re(CO)3(L-ASMA)]2− anion.

| 1H Signal | 2A (exo) | 2B (endo) |

|---|---|---|

| NH | 6.42 (m, 1H) | 6.18 (d, 1H, J=6.8 Hz) |

| Hα | 4.12 (m, 1H, J=5.6, 8.8 Hz) | 3.63 (dd, 1H, J=6.0, 8.0 Hz) |

| Hβ | 2.79 (dd, 1H, J=5.6,16.4 Hz) | 2.70 (d, 2H, J=6.0 Hz) |

| 2.55 (dd, 1H, J=8.8,16.4 Hz) | 2.70 (d, 2H, J=8.0 Hz) | |

| exo-HCOORD; | 3.58 (m, 2H) | 3.93 (dd, 1H, J=6.8, 17.2 Hz) |

| endo-HCOORD | 3.67 (d, 1H, J=17.2 Hz) |

Comparisons of the 1H NMR signals of Hα, NH, and HCOORD of 2A and 2B (Figure 7; these protons are bonded to C5, N1, and C6 respectively, Figure 5) are especially helpful for confirming the structure of 2A. Perhaps most enlightening are differences in the shielding of Hα in endo-Re(CO)3(ASMA) and exo-Re(CO)3(ASMA). Data from our previous work (Table 3) suggest that protons in an exo- orientation (away from the tricarbonyl face) are more shielded than those in an endo- orientation, resulting in an upfield shift in the 1H NMR signal. The orientation of the uncoordinated group can be inferred from the shift of Hα, as these two groups must assume opposing orientations. The Hα signal in 2B (3.63 ppm) is significantly upfield of the analogous signal from 2A (4.12 ppm). Therefore, Hα of 2A must assume the endo- orientation, as in exo-Re(CO)3(ASMA).

Table 3.

Comparison of 1H NMR shifts (ppm) of exo- and endo- proton signals in various ReI tricarbonyl complexes. Endo- protons are generally deshielded compared to analogous exo- protons.

The splitting pattern of the NH signals provides additional support for the structural assignment of 2A. NH has three neighboring protons (Hα and exo- and endo-HCOORD) likely to contribute to splitting of its 1H NMR signal. In each diastereomer (2A and 2B), the NH proton is in an endo- orientation, allowing for straightforward comparisons of signal splitting owing to the relative spatial arrangement of neighboring protons. As we observed earlier, the orientation of Hα is opposite to that of the uncoordinated acetate group. Thus, the NH signal in endo-Re(CO)3(ASMA) (2B) can be split by exo-Hα, exo-HCOORD and endo-HCOORD (see Figure 5), whereas the NH signal in exo-Re(CO)3(ASMA) can be split by endo-Hα, exo-HCOORD and endo-HCOORD. This difference is significant because, according to the crystal structure of 2B, both exo-HCOORD and exo-Hα protons in 2B have torsion angles near 90° with NH (exo-HCOORD–C6–N1–H = 94.3° and exo-Hα–C5–N1–H = 89.3°), resulting in a coupling constant of essentially zero (Figure 5a). Consequently, in 2B only coupling between NH and endo-HCOORD is observed, resulting in a distinct doublet at 6.18 ppm. For exo-Re(CO)3(ASMA), we expect to see NH splitting from both endo-Hα and endo-HCOORD and assume that splitting from exo-HCOORD is not observed because of a nearly orthogonal torsion angle with NH, similar to that observed in 2B. The NH splitting in 2A matches this expectation and resembles a triplet (6.42 ppm), suggesting that the coupling constants with Hα and endo-HCOORD are similar, and allowing us to confirm the assignment of 2A (and 4A) as exo-Re(CO)3(ASMA).

In addition, we expect the uncoordinated acetate group to shield the adjacent amine proton (NH) relative to its spatial proximity. In endo-Re(CO)3(ASMA) (see crystal structure of 2B in Figure 5a), the uncoordinated CH2CO2H group will be closer to the amino proton, causing the NH signal to be more shielded and hence shifting the resulting 1H NMR signal upfield (6.18 ppm) relative to the analogous NH signal (6.42 ppm) arising from exo-Re(CO)3(ASMA) (Table 2).

Conclusions

We have prepared Re(CO)3(ASMA) as an analogue of a potential new renal tracer, 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA), through methods that mimic 99mTc(CO)3+ labeling procedures. We demonstrated by following the reaction progress that the major products formed are analogous to those observed during the preparation of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA). As predicted on the basis of previously characterized M(CO)3+ complexes, the major isomers of M(CO)3(ASMA) have a facial, tridentate, ONO coordination mode with ASMA, forming two adjacent five-membered chelate rings. Coordination of either l-ASMA or d-ASMA yields a mixture of two diastereomeric complexes differing only in the position and orientation of the uncoordinated acetate group (-CH2CO2−) on the aspartate chelate ring. The detailed characterization of Re(CO)3(ASMA) isomers reinforces trends regarding the coordination of aminopolycarboxylate ligands to the MI-tricarbonyl core, such as preferred donor groups, chelate ring size, and coordination mode.

By examining the isomerization of diastereomeric products by HPLC we have identified endo-Re(CO)3(ASMA) (2B or 4B) as the thermodynamically favored product and exo-Re(CO)3(ASMA) (2A or 4A) as the kinetically favored product. We also followed the isomerization of Re(CO)3(ASMA) and outlined conditions for a practical isomerization favoring the thermodynamic product in a 9:1 ratio. This result has proved to be useful in NMR studies and in obtaining X-ray quality crystals. Because different isomeric species typically have different pharmacokinetic characteristics, the ability to control the endo/exo ratio may provide for the approximate isolation of a single 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) species, thus enhancing the effect of the isomer with optimal imaging and pharmacokinetic characteristics. In addition, the characterization of 99mTc(CO)3(ASMA) through Re analogues will allow for subsequent evaluations of pharmacokinetic properties to be correlated to its structural features, helping to guide the design of potential new 99mTc radiopharmaceuticals.

Experimental Section

General Procedures

All reagents and solvents were purchased as reagent grade and used without further purification. Aspartic-N-monoacetic acid (ASMA) was synthesized as previously reported as both the racemic mixture[12e] and the optically active l-isomer,[12a] briefly described below. Triaquatricarbonyl-rhenium(I) trifluoromethanesulfonate was prepared as previously reported and used as a 0.1 M stock solution.[8] Gel filtration was performed over Sephadex G-15 beads, eluting with deionized water at a rate of 0.5 mL/min. Ion exchange chromatography was performed using Dowex 50WX4 resin, in the H+ form. The products were washed with water, then eluted with 0.5 M NH4OH. 1H NMR spectra were obtained at room temperature in deuterium oxide, on a 400 MHz Varian NMR spectrometer. All chemical shifts were referenced to the water peak in D2O (4.80 ppm). HRMS was measured by the Emory University Mass Spectrometry Center by using a Thermo Finnigan LTQ-FTMS. HPLC analyses were performed on a Waters Breeze system equipped with a Waters 2487 dual wavelength absorbance detector, Waters 1525 binary pump, and XTerra MS C18 column (5 µm; 4.6 × 250 mm), using a flow rate of 1 mL/min gradient method described previously, with aqueous 0.05 M triethylammonium phosphate buffer, pH 2.5, as solvent A and methanol as solvent B.[9a] Elemental analyses were performed by Atlantic Microlabs, Atlanta, GA. Optical rotation was measured at 589 nm on a Perkin Elmer 541 polarimeter.

l-(N-carboxymethyl)aspartic acid (1, l-ASMA)

l-ASMA (1) was prepared as previously reported.[12a] Briefly, (L)-aspartic acid (0.13 g, 1.0 mmol) and bromoacetic acid (0.14 g, 1.0 mmol) were neutralized separately in water with 1 M NaOH (2 mL, 2.0 mmol) and combined. The resulting solution (10 mL) was heated to 70 °. The pH was maintained at 11 by frequent addition of 1 M NaOH, totaling 4.0 mL. No base was added after 1 h, and the solution was heated an additional 2 h without any change in the pH. The pH was adjusted to 2 by using concentrated HCl, and any salt that crystallized was removed by filtration. The crude product was purified by ion exchange chromatography to yield 1 (0.127 g, 66%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR[12a] and optical rotation[12b] data matched those of the previously reported compound. 1H NMR (D2O, pH 4) δ 3.89 (dd, 1H, J=3.2, 4.4 Hz); 3.72 (d, 1H, J=10.8 Hz); 3.64 (d, 1H, J=10.8 Hz); 2.91 (dd, 1H, J=3.2, 12.0 Hz); 2.85 (dd, 1H, J=4.4, 12.0 Hz). 13C NMR (D2O, pH 2) δ 37.5, 51.6, 61.3, 173.9, 175.3, 177.6. (c 1.0, H2O). HRMS (ESI): Calcd m/z for C6H10O6N (M+), 192.05026; found, 192.05003 (Δ = −0.23 mmu, −1.22 ppm).

Re(CO)3(l-ASMA) (2)

An aqueous solution of l-ASMA (0.020 g, 0.1 mmol, 5 mL) was neutralized with 1 M NaOH (0.1 mL, 0.1 mmol) and added to a stirred solution of [Re(CO)3(H2O)3]OTf (0.1 mmol, 0.1 M, 1.0 mL). The reaction mixture was heated at 70 °C for 30 min. Aqueous NaOH was added as needed to maintain the pH at 6. HPLC analysis of the reaction mixture revealed two peaks having retention times of 16.3 min (2A) and 17.3 min (2B) in a 2:1 ratio. The reaction mixture was concentrated to 1 mL and the products were purified by gel filtration. The UV-active fractions were analyzed by HPLC, and those without impurity were combined and concentrated under reduced pressure to yield a white solid (0.019 g, 38%). HRMS (ESI): Calcd m/z for C9H7O9N187Re (M-), 459.96839; found, 459.96846 (Δ = 0.07 mmu, 0.14 ppm). The 1H NMR spectrum showed two sets of peaks in a roughly 1:1 ratio. The mixture of isomers was heated at 70 °C for 2 d to isomerize the mixture to favor 2B, (2A:2B, 1:5). Differences in spectra before and after isomerization were used to determine which signals were derived from each isomer.

| 2A: | 1H NMR (D2O, pH 6) δ 6.42 (m, 1H); 4.12 (m, 1H, J=5.6, 8.8 Hz); 3.55 (m, 2H); 2.78 (dd, 1H, J=5.6, 16.4 Hz); 2.55 (dd, 1H, J=8.8, 16.4 Hz). |

| 2B: | 1H NMR (D2O, pH 6): δ 6.18 (d, 1H, J=6.8 Hz); 3.93 (dd, 1H, J=6.8, 17.2 Hz); 3.67 (d, 1H, J=17.2 Hz); 3.63 (dd, 1H, J=6.0, 8.0 Hz); 2.69 (d, 1H, J=8.0 Hz); 2.68 (d, 1H, J=6.0 Hz). |

d-(N-carboxymethyl)aspartic acid (3, d-ASMA)

d-ASMA (3) was prepared similarly to 1, by using d-aspartic acid instead of l-aspartic acid. The product was purified by ion exchange chromatography to yield 3 (0.105 g, 55%) as a colorless oil. The 1H NMR spectrum was identical to that of 1. 1H NMR (D2O, pH 4) δ 3.89 (dd, 1H, J=3.2, 4.4 Hz); 3.72 (d, 1H, J=10.8 Hz); 3.64 (d, 1H, J=10.8 Hz); 2.91 (dd, 1H, J=3.2, 12.0 Hz); 2.85 (dd, 1H, J=4.4, 12.0 Hz). 13C NMR (D2O, pH 2) δ 37.5, 51.6, 61.3, 173.9, 175.3, 177.6. (c 1.0, H2O). HRMS (ESI): Calcd m/z for C6H10O6N (M+), 192.05026; found, 192.05014 (Δ = −0.12 mmu, −0.64 ppm).

Re(CO)3(d-ASMA) (4)

The reaction of d-ASMA (0.075 g, 0.39 mmol, 5 mL) with [Re(CO)3(H2O)3]OTf (0.27 mmol, 0.1 M, 2.7 mL) proceeded in an identical manner as that used to prepare 2 to yield a white solid (0.085 g, 69%). 1H NMR spectrum was identical to that of 2. HRMS (ESI): Calcd m/z for C9H7O9N187Re (M-), 459.96839; found, 459.96857 (Δ = 0.18 mmu, 0.38 ppm).

(+/−)-(N-carboxymethyl)aspartic acid (5, rac-ASMA)

This compound was synthesized as previously reported.[12e] Briefly, glycine (0.075 g, 1.0 mmol) and maleic acid (0.128 g, 1.1 mmol) were combined in 10 mL of water. The pH of this mixture was adjusted to 11 with 1 M aqueous potassium hydroxide. The solution was heated near 70 °C for 1 d. The pH was adjusted to 2 with concentrated HCl and the mixture was cooled to 0 °C to precipitate KCl and starting materials. The filtrate was concentrated to yield a white solid (0.164 g) that contained some KCl. The elaborate purification method employed for 1 produced 5 (0.077 g, 40%) in high purity for 1H NMR and HRMS analyses; however, the crude product was sufficiently pure for use in the next step. The 1H NMR spectrum agreed with that of the previously reported compound. 1H NMR (D2O, pH 6) δ 3.84 (dd, 1H, J=4.4, 7.6 Hz); 3.70 (d, 1H, J=16.4 Hz); 3.64 (d, 1H, J=16.4 Hz); 2.83 (dd, 1H, J=4.0, 17.6 Hz); 2.75 (dd, 1H, J=7.6, 17.6 Hz). 13C NMR (D2O, pH 3) δ 37.5, 51.3, 61.7, 174.3, 175.7, 178.9. (c 1.0, H2O). HRMS (ESI): Calcd m/z for C6H8O6N (M-), 190.03571; found, 190.03565 (Δ = −0.06 mmu, −0.32 ppm).

Re(CO)3(rac-ASMA) (2 and 4)

To an aqueous solution of crude rac-ASMA (5, 0.034 M, 0.068 mmol, 2 mL) was added NMe4OH·5H2O (0.038 g, 0.21 mmol) and [Re(CO)3(H2O)3]OTf (0.068 mmol, 0.1 M, 0.68 mL), and the solution was heated at 70 °C for 30 min. HPLC analysis of the reaction mixture was identical to that of 2, with two peaks having retention times of 16.3 min (2A and 4A) and 17.3 min (2B and 4B) in a ca. 2:1 ratio. The reaction mixture was concentrated to 1 mL and the products were purified by gel filtration as described above for 2 to yield the products as a white solid (0.031 g, 75%). 1H NMR and HRMS data were identical to the data for 2 and 4. The product was equilibrated (70 °C, pH 7, 1 d) and the endo- product was crystallized from a concentrated aqueous solution (pH 2) at room temperature as a potassium salt (the K+ cation is present in the crude starting material, 5).

Anal. Calcd for C9H7N9OReK: C, 21.69; H, 1.42, N, 2.81; Found: C, 21.74; H, 1.35; N, 2.81.

Crystal structure of K[endo-Re(CO)3(rac-ASMA)]

A suitable crystal was coated with Paratone N oil, suspended in a small fiber loop and placed in a cooled nitrogen gas stream at 173 K on a Bruker D8 APEX II CCD sealed tube diffractometer with graphite monochromated MoKα (0.71073 Å) radiation. Data were measured by using a series of combinations of phi and omega scans with 10 s frame exposures and 0.5° frame widths. Data collection, indexing and initial cell refinements were all carried out with APEX II[15] software. Frame integration and final cell refinements were done by using SAINT[15] software. The final cell parameters were determined from least-squares refinement on 4395 reflections.

The structure was solved by using direct methods and difference Fourier techniques (SHELXTL, V6.12).[16] Hydrogen atoms were placed in their expected chemical positions by using the HFIX command and were included in the final cycles of least squares with isotropic Uij’s related to the atoms ridden upon. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. Scattering factors and anomalous dispersion corrections were taken from the International Tables for X-ray Crystallography.[17] Structure solution, refinement, graphics and generation of publication materials were performed by using SHELXTL, V6.12 software. These results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Additional details of the data collection and structure refinement of K[endo-Re(CO)3(rac-ASMA)].

| 2B and 4B | |

|---|---|

| empirical formula | C9H7KNO9Re |

| formula weight | 498.46 |

| T (K) | 173 (2) |

| λ (Å) | 0.71073 |

| crystal system | monoclinic |

| space group | P21/c |

| unit cell dimensions | |

| a (Å) | 7.952 (4) |

| b (Å) | 14.774 (7) |

| c (Å) | 10.879 (5) |

| β (deg) | 98.417 (7) |

| V (Å3) | 1264.4 (10) |

| Z | 4 |

| ρcalc (mg/m3) | 2.619 |

| abs coeff (mm−1) | 9.988 |

| R indices [I > 2σ(I)] | R1 = 0.0260 |

| wR2 = 0.0590 |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Grant No. R37 DK38842). The authors thank Dr. Kenneth Hardcastle of Emory University for discussions regarding crystal preparation and for the structure determination. We also thank Dr. Patricia A. Marzilli for her invaluable comments during the preparation of the paper.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.eurjic.org/ or from the author.

References

- 1.Lo K, Zhang K, Li S. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011:3551–3568. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louie AS, Vasdev N, Valliant JF. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:3360–3367. doi: 10.1021/jm2001162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fricker SP, Mosi RM, Cameron BR, Baird I, Zhu Y, Anastassov V, Cox J, Doyle PS, Hansell E, Lau G, Langille J, Olsen M, Qin L, Skerlj R, Wong RSY, Santucci Z, McKerrow JH. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008;102:1839–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) García Garayoa E, Rüegg D, Bläuenstein P, Zwimpfer M, Khan I, Maes V, Blanc A, Beck-Sickinger AG, Tourwé DA, Schubiger PA. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2007;34:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Esteves T, Xavier C, Gama S, Mendes F, Raposinho PD, Marques F, Paulo A, Pessoa JC, Rino J, Viola G, Santos I. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:4104–4116. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00073f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Sagnou M, Benaki D, Triantis C, Tsotakos T, Psycharis V, Raptopoulou CP, Pirmettis I, Papadopoulos M, Pelecanou M. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:1295–1303. doi: 10.1021/ic102228u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Abram U, Braun M, Abram S, Kirmse R, Voigt A. Dalton Trans. 1998:231–238. [Google Scholar]; b) Nguyen HH, Jegathesh JJ, Maia PIdS, Deflon VM, Gust R, Bergemann S, Abram U. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:9356–9364. doi: 10.1021/ic901160v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toganoh M, Ikeda S, Furuta H. Chem. Commun. 2005:4589–4591. doi: 10.1039/b508208k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alberto R, Kyong Pak J, van Staveren D, Mundwiler S, Benny P. Pept. Sci. 2004;76:324–333. doi: 10.1002/bip.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He H, Lipowska M, Xu X, Taylor AT, Carlone M, Marzilli LG. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:5437–5446. doi: 10.1021/ic0501869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) He H, Lipowska M, Xu X, Taylor AT, Marzilli LG. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:3385–3394. doi: 10.1021/ic0619299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lipowska M, He H, Xu X, Taylor AT, Marzilli PA, Marzilli LG. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:3141–3151. doi: 10.1021/ic9017568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lipowska M, Cini R, Tamasi G, Xu X, Taylor AT, Marzilli LG. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:7774–7783. doi: 10.1021/ic049544i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) He H, Lipowska M, Christoforou AM, Marzilli LG, Taylor AT. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2007;34:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Lipowska M, Klenc J, Marzilli LG, Taylor AT. J. Nucl. Med. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipowska M, Klenc J, Malveaux E, Marzilli L, Taylor A. J. Nucl. Med. 2011;52:103P. [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) He H, Morley JE, Twamley B, Groeneman RH, Bučar D-Ki, MacGillivray LR, Benny PD. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:10625–10634. doi: 10.1021/ic901159r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Makris G, Karagiorgou O, Papagiannopoulou D, Panagiotopoulou A, Raptopoulou CP, Terzis A, Psycharis V, Pelecanou M, Pirmettis I, Papadopoulos MS. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Snyder RV, Angelici RJ. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1973;35:523–535. [Google Scholar]; b) Korman S, Clarke HT. J. Biol. Chem. 1956;221:133–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Miyazawa T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1980;59:2555–2565. [Google Scholar]; d) Takahashi KN. T., JP 07089913. 1995 [Google Scholar]; e) Hartman JAR, Woodbury RP. 5,362,412 US. 1994

- 13.Lipowska M, Taylor AT, Marzilli LG. In: Technetium and other radiometals in chemistry and medicine. Mazzi U, Eckelman WC, Volkert WA, editors. SGEditoriali, Padova: 2010. pp. 281–284. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Correia JDG, Domingos Â, Santos I, Alberto R, Ortner K. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:5147–5151. doi: 10.1021/ic010417l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruker APEX2, Program Suite for Crystallographic Software. Madison (USA): Bruker AXS Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheldrick GM. Acta Cryst. 2008;A64:112–122. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson AJC, editor. International Tables for X-ray Crystallography, Vol. C. Dordrecht: Academic Publishers; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chem 3D Pro, Desktop Modelling Application Suite. Cambridge, MA: CambridgeSoft; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.