Abstract

Though congenital anomalies of the pancreas and pancreatic duct are relatively uncommon and they are often discovered as an incidental finding in asymptomatic patients, some of these anomalies may lead to various clinical symptoms such as recurrent abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. Recognition of these anomalies is important because these anomalies may be a surgically correctable cause of recurrent pancreatitis or the cause of gastric outlet obstruction. An awareness of these anomalies may help in surgical planning and prevent inadvertent ductal injury. The purpose of this article is to review normal pancreatic embryology, the appearance of ductal anatomic variants and developmental anomalies of the pancreas, with emphasis on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography and multidetector computed tomography.

Keywords: Pancreas, Congenital, Pancreas divisum, Annular pancreas, Accessory pancreatic lobe

INTRODUCTION

Congenital anomalies and normal variants of the pancreas and pancreatic duct may not be detected until adulthood and they are often discovered as an incidental finding in asymptomatic patients. In adult patients with persistent and unexplained signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting resulting from recurrent pancreatitis or gastric outlet obstruction, a developmental anomaly of the pancreas and pancreatic duct should be considered and imaging is recommended. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography (MRCP) is being used with increasing frequency in the noninvasive evaluation of the biliary tree and pancreatic duct. It may depict the course and drainage pattern of the pancreatic duct and easily diagnose developmental anomalies of the pancreas. MRCP is especially appropriate for the assessment of congenital pancreatic anomalies since it depicts ductal anatomy rapidly and noninvasively without risk of acute pancreatitis (1). Recent improvement in spiral computed tomography (CT) technology, such as multidetector and subsecond rotation time, have made it possible to scan the biliary tree and pancreas with a collimation of 1 mm and less. The superior resolution in the z-axis and multiplanar reconstruction images allows the selection of the optimal sectional planes for the assessment of pancreatic and bile ducts (1, 2).

Anatomic variations and developmental anomalies of the pancreas and pancreatic duct include variations of the course of the pancreatic duct (descending, sigmoid, vertical and loop shaped course), variation of the configuration of the pancreatic duct (bifid configuration with dominant duct of Wirsung, dominant duct of Santorini without divisum, absent duct of Santorini and ansa pancreatica), duplication anomalies, anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction, pancreas divisum, annular pancreas, ectopic pancreas, pancreatic agenesis and hypoplasia of the dorsal pancreas and accessory pancreatic lobe. Recognition of these anomalies is important because these anomalies may be a surgically correctable cause of recurrent pancreatitis or the cause of gastric outlet obstruction. An awareness of these anomalies may help in surgical planning and prevention of inadvertent ductal injury.

In this article, we review normal pancreatic embryology, the appearance of ductal anatomic variants and developmental anomalies of the pancreas, with emphasis on MRCP and multidetector computed tomography (MDCT).

Embryologic Development of the Pancreas

The pancreas develops from dorsal and ventral buds that first appear in the fifth gestational week as outgrowths of the primitive foregut (Fig. 1). By the seventh gestational week, expansion of the duodenum causes the ventral bud to rotate and pass behind the duodenum from right to left and fuse with the dorsal bud. The ventral bud forms the posterior head and uncinate process, whereas the dorsal bud forms the anterior head, body, and tail (3). Following this fusion, the ductal systems anastomose, a complicated process with a wide spectrum of possible outcomes. The portion of the ventral duct between the dorsal-ventral fusion and major papilla is termed the duct of Wirsung. The portion of the dorsal duct upstream to the dorsalventral fusion point is called the main pancreatic duct. The segment of the dorsal duct downstream to the dorsal-ventral fusion point is termed the duct of Santorini, or accessory pancreatic duct, which drains at the papilla minor (3).

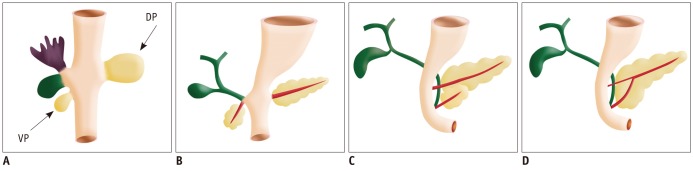

Fig. 1.

Drawings show normal embrologic development of pancreas.

Ventral pancreatic bud (VP) arises from hepatic diverticulum, and dorsal pancreatic bud (DP) arises from dorsal mesogastrium (A). During 7th gestational week, expansion of duodenum causes ventral pancreatic bud to rotate and pass behind duodenum from right to left and fuse with dorsal pancreatic bud (B-D). Ventral bud forms posterior head and uncinate process, whereas dorsal bud forms anterior head, body, and tail. Finally, ventral and dorsal pancreatic ducts fuse, and pancreas predominantly is drained through ventral duct, which joins common bile duct at level of major papilla and dorsal duct drains at level of minor papilla.

Variations of the Pancreatic Duct

The course of the pancreatic duct varies greatly and the most common one (50%) is a descending course. Other courses include sigmoid, vertical, and loop configurations (Figs. 2, 3) (1).

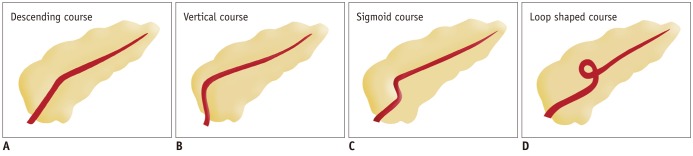

Fig. 2.

Drawings show variation in course of pancreatic duct.

(A) Descending (B) vertical (C) sigmoid (D) loop shaped course.

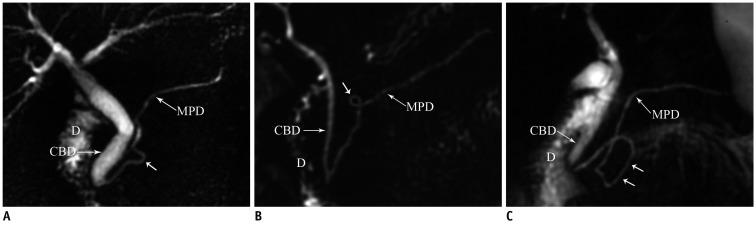

Fig. 3.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography images reveal variation in course of pancreatic duct.

A. Sigmoid shaped (arrow). B, C. loop shaped (arrows) course. CBD = common bile duct, D = duodenum, MPD = main pancreatic duct

The ductal configuration most commonly (60%) manifests as a bifid configuration with a dominant duct of Wirsung (Fig. 4). Less common configurations include an absent duct of Santorini (30%), a dominant duct of Santorini without divisum (1%), and 'ansa pancreatica', in which the duct of Santorini forms a reversed-S shape and connects with a side branch of the duct of Wirsung (Fig. 5) (4).

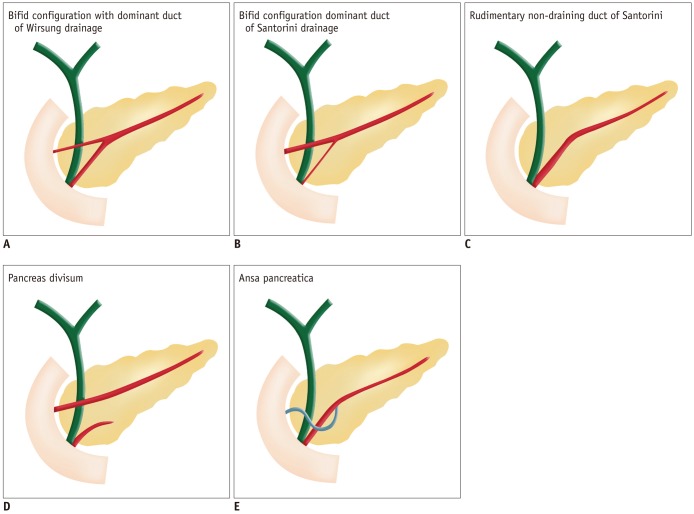

Fig. 4.

Drawings show variation in configuration of pancreatic duct.

(A) Bifid configuration with dominant duct of Wirsung drainage, (B) bifid configuration with dominant duct of Santorini drainage without divisum, (C) rudimentary non-draining duct of Santorini (D) pancreas divisum, (E) ansa pancreatica.

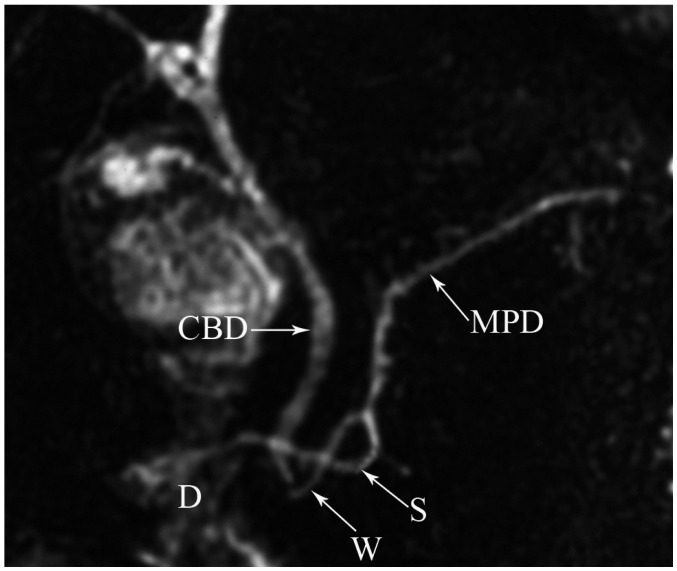

Fig. 5.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography image reveals typical inverted-S shape of duct of Santorini (S) in ansa pancreatica. CBD = common bile duct, D = duodenum, MPD = main pancreatic duct, W = Wirsung

Duplication anomalies of the main pancreatic duct are not uncommonly seen (Fig. 6). Cystic dilatations of terminal portions of the ducts of Wirsung and Santorini are termed Wirsungocele and Santorinicele (Fig. 7) (4).

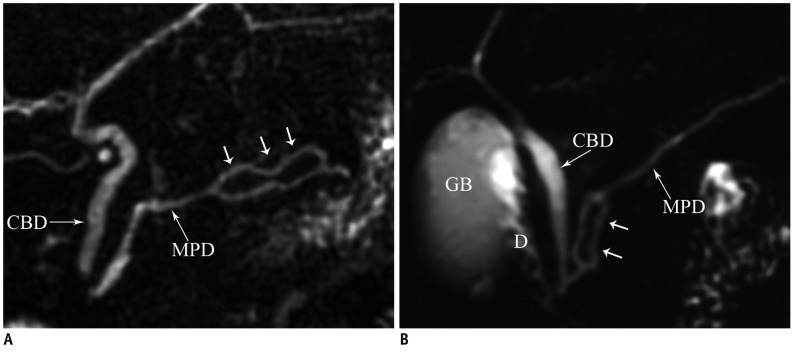

Fig. 6.

Duplication of pancreatic duct.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography images (A, B) show focal duplication (arrows) of pancreatic duct. CBD = common bile duct, D = duodenum, GB = gall bladder, MPD = main pancreatic duct

Fig. 7.

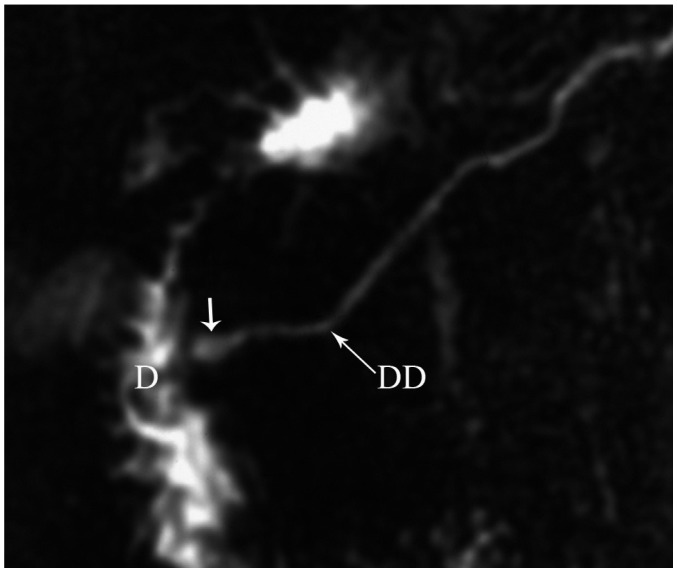

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography image reveals dominant dorsal duct (DD) with santorinicele (arrow) in pancreas divisum. D = duodenum

Anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction is characterized by fusion of the pancreatic duct and common biliary duct (CBD) outside the duodenal wall, with formation of a long common channel (> 15 mm) (Fig. 8). This anomaly is often associated with choledochal cyst formation and carcinoma in the biliary tract (5).

Fig. 8.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography image reveals long common channel (> 15 mm) (arrows) and associated Todani type 4a choledochal cysts with intrahepatic and extrahepatic components. CBD = common bile duct, MPD = main pancreatic duct

Developmental Anomalies of the Pancreas

Pancreas Divisum

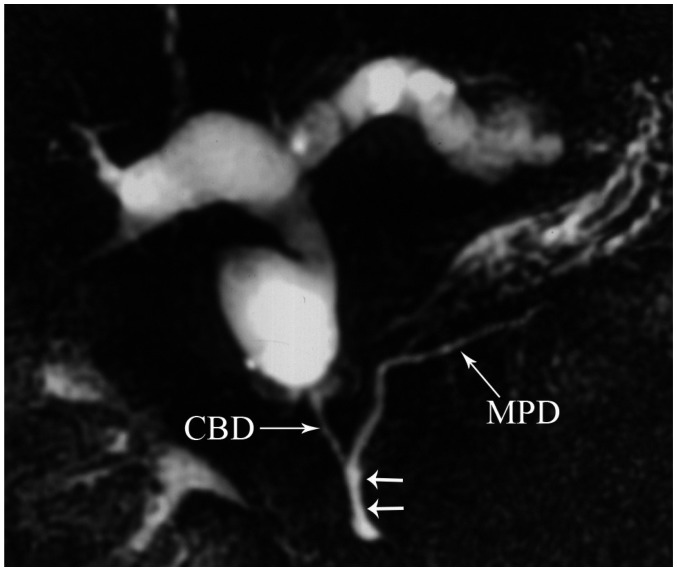

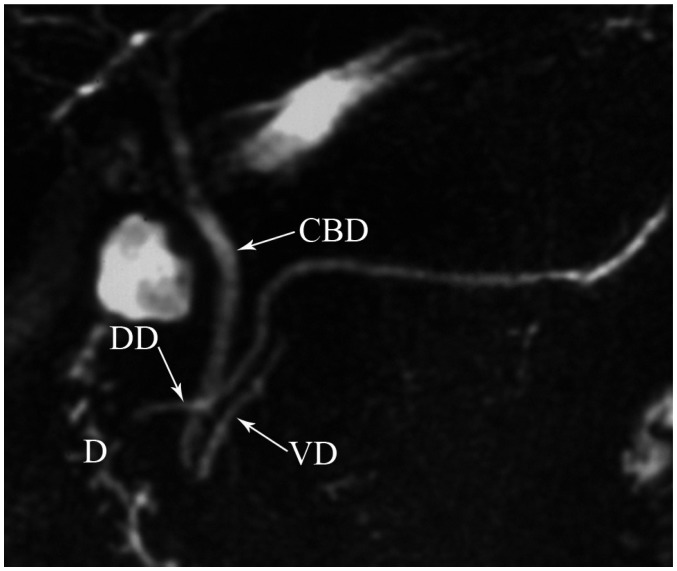

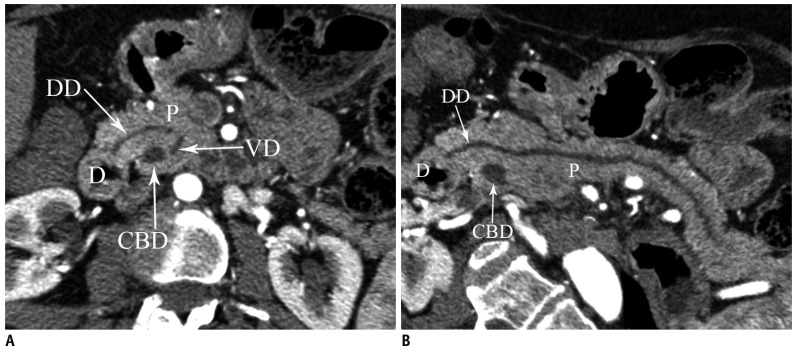

Pancreas divisum occurs in 4-14% of the population and results from failed fusion of the dorsal and ventral ducts during embyological development (3). Three variants have been described: type 1 or classical divisum in which there is total failure of fusion; type 2 in which dorsal drainage is dominant in the absence of the duct of Wirsung; and type 3 or incomplete divisum where a small communicating branch is present (6, 7). In pancreas divisum, the majority of the pancreatic gland drains into the minor papilla via the duct of Santorini, whereas the posterior head and uncinate process drain into the major papilla via the duct of Wirsung with the CBD (Fig. 9) (3). Although most patients are asymptomatic, in some patients, this anomaly is associated with recurrent acute pancreatitis because of inadequate drainage of pancreatic secretions via the minor papilla. MRCP enables a noninvasive diagnosis of the pancreas divisum without the use of contrast material and avoids the risk of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) induced acute pancreatitis (1). MDCT may also depict this anomaly, when the pancreatic duct is visualized. On axial images, the dorsal duct passes the terminal common bile duct anteriorly and superiorly (Fig. 10) (8). Rarely, pancreas divisum is associated with a focal cystic dilation of the terminal portions of the duct of Santorini, which is termed as a Santorinicele (Fig. 7) (4).

Fig. 9.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography image shows dorsal duct (DD) crossing anterior to common bile duct (CBD) and emptying separately into minor papilla and CBD joining with ventral duct (VD) and both entering into major papilla in patient with pancreas divisum. D = duodenum

Fig. 10.

Pancreas divisum.

Axial (A) and curved planar reformatted (B) MDCT images show dorsal duct (DD) crossing anterior to common bile duct (CBD) and emptying separately into minor papilla in patient with pancreas divisum. D = duodenum, P = pancreas, VD = ventral duct, MDCT = multidetector computed tomography

Annular Pancreas

Annular pancreas occurs in 1/20000 of the population and results from failure of the ventral bud to rotate with the duodenum, resulting in envelopment of the duodenum. In this anomaly, a band of pancreatic tissue encircles the second part of the duodenum, either completely or incompletely, and it is in continuity with the pancreatic head (3). Annular pancreas usually presents in neonates with vomiting due to severe duodenal obstruction. In adults, approximately 50% of the patients may be asymptomatic for life, with the anomaly discovered incidentally. When symptomatic, the presentation is usually in the third to sixth decade with abdominal pain, postprandial fullness and vomiting resulting from gastric outlet obstruction, upper gastrointestinal bleeding from peptic ulceration, acute or chronic pancreatitis, or in rare instances, jaundice resulting from biliary obstruction (9).

When the annular pancreatic duct encircling and extending to the right side of the duodenum is identified by MRCP or ERCP, the diagnosis of annular pancreas is established. But sometimes the pancreatic duct without dilatation is invisible on MRCP. Secretin-enhanced MRCP may be the best non-invasive imaging modality for evaluating ductal anatomy. The annular pancreatic duct usually communicates with the main pancreatic duct (Fig. 11) but may drain into the intrapancreatic common bile duct, the duct of Wirsung, or the duct of Santorini. At CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a ring of pancreatic tissue surrounds the descending duodenum, in continuity with the pancreatic head (Fig. 12) (10, 11). However, a visualization of a complete ring of pancreatic tissue around the duodenum is not required for a diagnosis of annular pancreas (9). Pancreatic tissue extending in a posterolateral or anterolateral direction to the second part of the duodenum or pancreatic tissue anterior and posterior to the duodenum ('crocodile jaw' configuration), in the presence of a gastric outlet obstruction should raise the suspicion of annular pancreas (Fig. 13) (9). It is most likely that these patients have a thin band of pancreatic tissue, not seen at CT and MRI, incorporated in the duodenal wall.

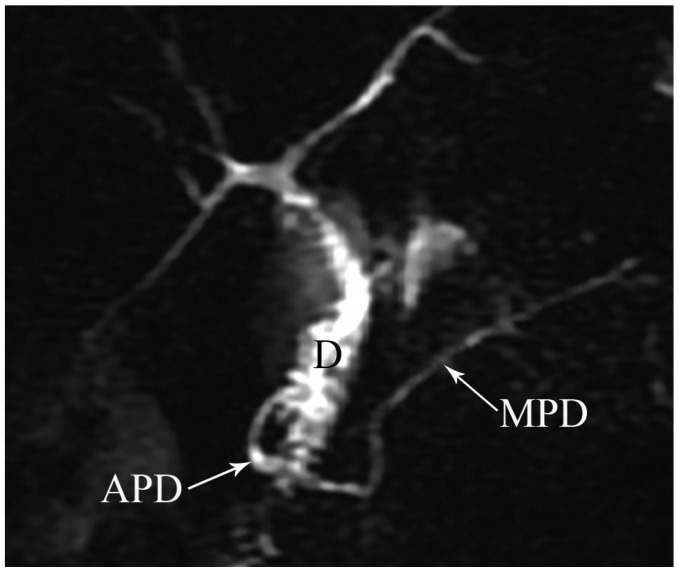

Fig. 11.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography image shows annular pancreatic duct (APD) communicating with main pancreatic duct (MPD) and completely encircling duodenum (D) in patient with annular pancreas.

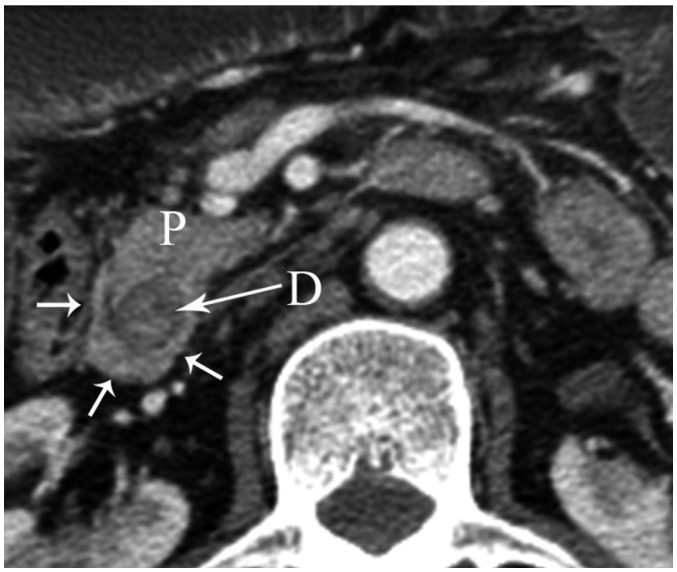

Fig. 12.

Axial MDCT image shows pancreatic tissue (arrows) completely encircling second part of duodenum (D) in patient with annular pancreas. P = pancreas, MDCT = multidetector computed tomography

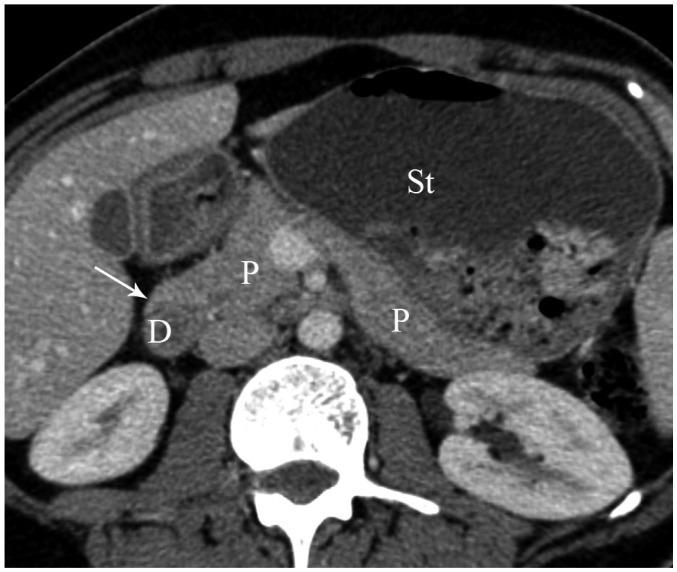

Fig. 13.

Axial MDCT image shows pancreatic tissue (arrow) extending in anterolateral direction to second part of duodenum (D) and dilatation of stomach (St) in patient with incomplete annular pancreas. P = pancreas, MDCT = multidetector computed tomography

Ectopic Pancreas

Ectopic (heterotopic) pancreas is described as a pancreatic tissue that lacks anatomic or vascular continuity with the normal pancreas. This incidence of this condition varies from 1% to 15%, depending on the reported series. Ectopic pancreas is most commonly (70%) located at the submucosa of the gastric antrum, proximal portion of the duodenum or the jejunum. Rarely it can also be found in the ileum, colon, appendix, mesentery, gallbladder or Meckel diverticulum. The ectopic tissue usually measures 0.5-2.0 cm in its larger diameter (rarely up to 5 cm) (12). This anomaly is usually asymptomatic and occurs as an incidental finding on gastroscopy, although complications such as ulceration, bleeding, intussusception and obstruction may develop. Rarely adenocarcinoma occuring in the ectopic pancreatic tissue may be seen (13).

At barium studies, ectopic pancreas is usually seen as a smooth, broad-based submucosal lesion in the greater curvature of the gastric antrum or in the proximal duodenum. A diagnostic feature is a central niche or umbilication, representing the orifice of the rudimentary pancreatic duct, containing a small collection of barium, seen in up to 45% of cases (12, 14). There are no specific diagnostic features at CT to differentiate ectopic pancreas from other submucosal masses.

Pancreatic Agenesis and Hypoplasia of the Dorsal Pancreas

Total agenesis of the pancreas is extremely rare and is incompatible with life. Hypoplasia (partial agenesis) results from the absence of the ventral or dorsal pancreatic anlage. Dorsal pancreatic agenesis (short pancreas) may be an isolated finding but has also been reported as a part of heterotaxia syndromes (Fig. 14) (15). In complete dorsal agenesis, the anterior head, neck, body and tail of the pancreas, the duct of Santorini and the minor papilla are absent. In partial dorsal agenesis, a variable amount of pancreatic tissue is absent but a remnant of the duct of Santorini and the minor papilla are present. Patients with dorsal pancreatic agenesis have an increased risk of diabetes mellitus because most of the islet cells are located in the distal pancreas (16).

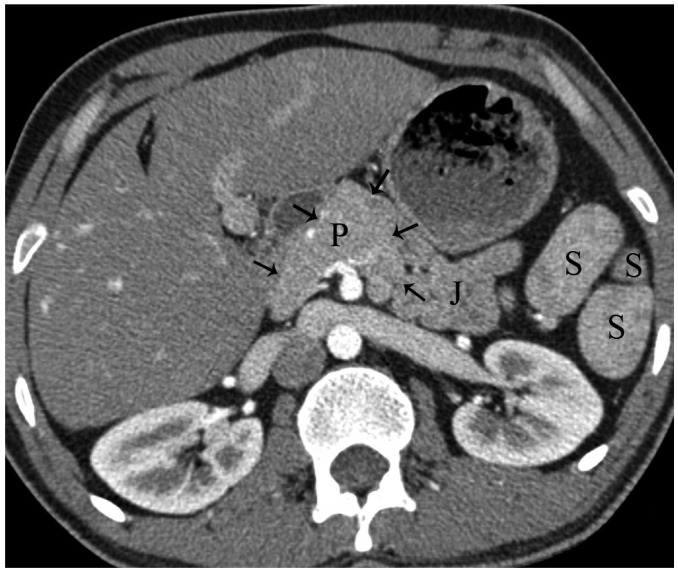

Fig. 14.

Axial MDCT image shows partial dorsal agenesis of pancreas (arrows) in patient with polysplenia syndrome. P = pancreas, J = jejunum, S = spleen, MDCT = multidetector computed tomography

Accessory Pancreatic Lobe

The accessory pancreatic lobe, an extremely rare anomaly, is defined as an accessory lobe of pancreatic tissue originating from the main pancreatic gland and containing an aberrant duct (17). The accessory lobe may be short or long, with a wide or narrow connection to the main portion of the pancreas. This anomaly is usually associated with a gastric duplication cyst and the aberrant duct communicates with the main pancreatic duct and the duplication cyst (Fig. 15) (17). Recurrent acute pancreatitis is the most common (66%) clinical manifestation of this anomaly. The underlying cause of recurrent acute pancreatitis is hypothesized to be obstruction of the pancreatic duct by viscous mucus secretions, ulcer bleeding or biliary sludge (17).

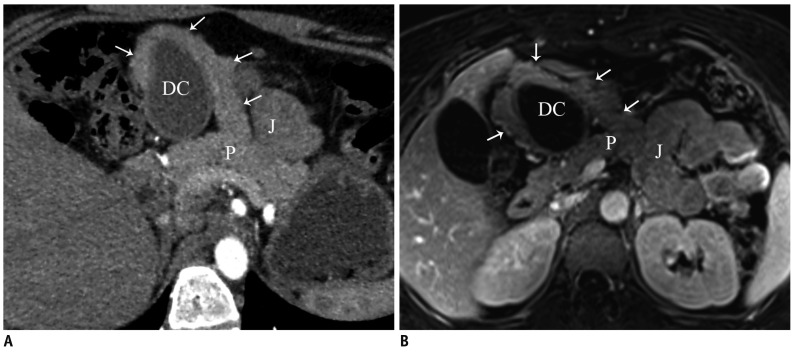

Fig. 15.

Accessory pancreatic lobe.

Oblique axial (A) and fat suppressed contrast-enhanced T1-weighted gradient echo (B) MR images show accessory pancreatic lobe (arrows) that has similar attenuation and signal intensity to pancreatic tissue (P), arising from pancreas, projecting anteriorly and attaching to gastric duplication cyst (DC). P = pancreas, J = jejunum

Variations of Pancreatic Contours

The head and neck portions of the pancreas may have lobulated contours, especially in the lateral aspect, mimicking a pancreatic tumor, peripancreatic metastatic tumor deposit or lymphadenopathy (Fig. 16). The attenuation or signal intensity of the lobular pancreas is the same as the normal pancreatic tissue in all phases, including unenhanced, arterial, pancreatic parenchymal and portal phases. This is the key point that helps to differentiate this condition from a pancreatic neoplasm (12).

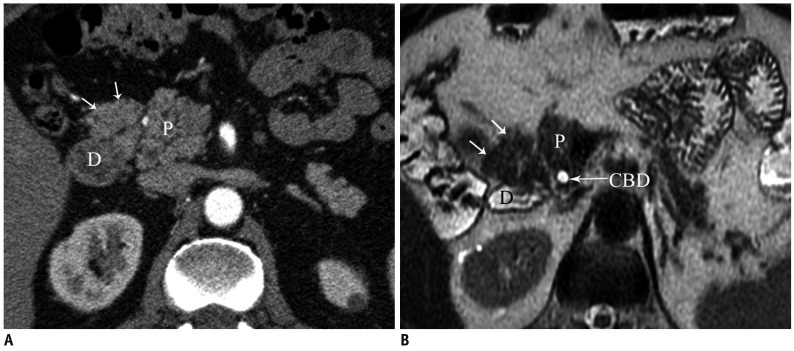

Fig. 16.

Variations of pancreatic contours.

Axial MDCT (A) and T2-weighted MR (B) images show soft tissue protuberance (arrows) that has similar attenuation and signal intensity to pancreatic head (P). C = common bile duct, CBD = common biliary duct, D = duodenum, P = pancreas

CONCLUSION

Congenital anomalies of the pancreas and pancreatic duct are not uncommonly encountered at radiologic examinations. Radiologists should be aware of these anomalies and their variable imaging features to distinguish them from other pancreatic conditions. MRCP is the imaging modality of choice for the work-up of suspected developmental anomalies of the pancreas and pancreatic duct. It may depict noninvasively the course and drainage pattern of the pancreatic duct and can easily diagnose developmental anomalies of the pancreas. Alternatively, multiplanar reconstructed MDCT images with thin slices may allow the identification of congenital anomalies of the pancreatic duct and pancreas. Recognition of developmental anomalies of the pancreas and pancreatic duct is important because these anomalies may be a surgically correctable cause of recurrent pancreatitis or the cause of gastric outlet obstruction. An awareness of these anomalies may help in surgical planning and prevention of inadvertent ductal injury.

References

- 1.Itoh S, Ikeda M, Ota T, Satake H, Takai K, Ishigaki T. Assessment of the pancreatic and intrapancreatic bile ducts using 0.5-mm collimation and multiplanar reformatted images in multislice CT. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:277–285. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1516-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Itoh S, Fukushima H, Takada A, Suzuki K, Satake H, Ishigaki T. Assessment of anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal junction with high-resolution multiplanar reformatted images in MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:668–675. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulte SJ. Embryology, normal variation, and congenital anomalies of the pancreas. In: Stevenson GW, Freeny PC, Margulis AR, Burhenne HJ, editors. Margulis' and Burhenne's alimentary tract radiology. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1994. pp. 1039–1051. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mortelé KJ, Rocha TC, Streeter JL, Taylor AJ. Multimodality imaging of pancreatic and biliary congenital anomalies. Radiographics. 2006;26:715–731. doi: 10.1148/rg.263055164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cha SW, Park MS, Kim KW, Byun JH, Yu JS, Kim MJ, et al. Choledochal cyst and anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union in adults: radiological spectrum and complications. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2008;32:17–22. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e318064e723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozu T, Suda K, Toki F. Pancreatic development and anatomical variation. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1995;5:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quest L, Lombard M. Pancreas divisum: opinio divisa. Gut. 2000;47:317–319. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soto JA, Lucey BC, Stuhlfaut JW. Pancreas divisum: depiction with multi-detector row CT. Radiology. 2005;235:503–508. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2352040342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandrasegaran K, Patel A, Fogel EL, Zyromski NJ, Pitt HA. Annular pancreas in adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:455–460. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizzo RJ, Szucs RA, Turner MA. Congenital abnormalities of the pancreas and biliary tree in adults. Radiographics. 1995;15:49–68. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.15.1.7899613. quiz 147-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nijs EL, Callahan MJ. Congenital and developmental pancreatic anomalies: ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging features. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2007;28:395–401. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu J, Turner MA, Fulcher AS, Halvorsen RA. Congenital anomalies and normal variants of the pancreaticobiliary tract and the pancreas in adults: part 2, Pancreatic duct and pancreas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:1544–1553. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emerson L, Layfield LJ, Rohr LR, Dayton MT. Adenocarcinoma arising in association with gastric heterotopic pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:53–57. doi: 10.1002/jso.20087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander LF. Congenital pancreatic anomalies, variants, and conditions. Radiol Clin North Am. 2012;50:487–498. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Low JP, Williams D, Chaganti JR. Polysplenia syndrome with agenesis of the dorsal pancreas and preduodenal portal vein presenting with obstructive jaundice--a case report and literature review. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:e217–e220. doi: 10.1259/bjr/27680217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lång K, Lasson A, Müller MF, Thorlacius H, Toth E, Olsson R. Dorsal agenesis of the pancreas - a rare cause of abdominal pain and insulin-dependent diabetes. Acta Radiol. 2012;53:2–4. doi: 10.1258/ar.2011.110480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oeda S, Otsuka T, Akiyama T, Ario K, Masuda M, Taguchi S, et al. Recurrent acute pancreatitis caused by a gastric duplication cyst communicating with an aberrant pancreatic duct. Intern Med. 2010;49:1371–1375. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]