Abstract

Men with prostate cancer who receive androgen deprivation therapy show profound skeletal muscle loss. We hypothesized that the androgen deficiency activates not only the ubiquitin-proteasome systems but also the autophagy and affects key aspects of the molecular cross talk between protein synthesis and degradation. Here, 2-month-old male mice were castrated and treated with either testosterone (T) propionate or vehicle for 7 days (short term) or 43 days (long term), and with and without hydroxyflutamide. Castrated mice showed rapid and profound atrophy of the levator ani muscle (high androgen responder) at short term and lesser atrophy of the triceps muscle (low androgen responder) at long term. Levator ani and triceps muscles of castrated mice showed increased level of autophagy markers and lysosome enzymatic activity; only the levator ani showed increased proteasomal enzymatic activity. The levator ani muscle of the castrated mice showed increased level and activation of forkhead box protein O3A, the inhibition of mechanistic target of rapamicyn, and the activation of tuberous sclerosis complex protein 2 and 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase. Similar results were obtained in the triceps muscle of castrated mice. T rescued the loss of muscle mass after orchiectomy and inhibited lysosome and proteasome pathways dose dependently and in a seemingly IGF-I-dependent manner. Hydroxyflutamide attenuated the effect of T in the levator ani muscle of castrated mice. In conclusion, androgen deprivation in adult mice induces muscle atrophy associated with proteasomal and lysosomal activity. T optimizes muscle protein balance by modulating the equilibrium between mechanistic target of rapamicyn and 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase pathways.

Androgen deficiency in men, a syndrome characterized by reduced production of testosterone (T) due to defects of the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis, is associated with a loss of skeletal muscle mass, which contributes to adverse health outcomes. A particularly striking illustration of the effects of androgen deficiency is observed in men who receive androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. These patients experience substantial loss of muscle mass after institution of ADT, which renders them susceptible to increased risk of physical limitations, frailty, and falls (1, 2). The mechanisms by which T deficiency leads to loss of skeletal muscle mass remain poorly understood.

At steady state, skeletal muscle mass can be viewed as a net balance between muscle protein synthesis and degradation. Thus, the loss of muscle mass in response to androgen deprivation can occur either as a result of decreased protein synthesis or increased protein breakdown or some combination of both. Anabolic stimuli, such as mechanical loading and nutrient supplementation, increase muscle mass by augmenting net protein balance (3), whereas catabolic stimuli, such as starvation (4) and mechanical unloading (5), induce rapid muscle atrophy, which is mediated by the ubiquitin (Ub)-proteasome system (UPS) and by the autophagy/lysosome pathway (ALP). The UPS targets proteins for degradation by linking them to a chain of Ub molecules. Muscle ring finger1 (MuRF1) and muscle atrophy F-box (MAFbx) are UPS E3-Ub ligases induced during some types of muscle atrophy (6, 7). MuRF1 and MAFbx gene expression is regulated by forkhead box protein O (FoxO)1, FoxO3, and Kruppel-like factor 15 (Klf15) transcription factors (8, 9). Many anabolic stimuli block FoxOs nuclear entry to prevent muscle catabolism; for instance, IGF-I represses MuRF1 and MAFbx gene expression through the Akt-mediated phosphorylation of FoxOs (10). ALP is characterized by the formation of autophagosomes, which segregate the cellular material that will be destroyed after fusion with lysosomes (11). UPS and ALP are functionally linked, as demonstrated by the FoxO-mediated expression of many autophagy genes, eg, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3β (LC3B) and BCL2/adenovirus E1b-interacting protein 3 (Bnip3) (12, 13).

The serine/threonine kinase mechanistic target of rapamicyn (mTOR) regulates cell size, metabolism, and growth (14). When sufficient amino acids are available, mTOR localizes on the surface of lysosomes, a step required for mTOR to enhance protein synthesis and for its inhibitory effect on autophagy (15–18). mTOR activity is also controlled by the 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) complex, the main energy sensor of the cell (19). AMPK is activated by cellular stresses that increase the AMP-ADP to ATP ratio, eg, starvation and physical exercise. In these contexts, the catalytic subunits of the AMPK complex, the serine/threonine kinases AMPKα1 and AMPKα2, inhibit mTOR to down-regulate energy consuming processes, eg, protein synthesis, and to up-regulate proteasome and autophagy (18–23).

The effects of T supplementation on muscle protein synthesis and degradation have been inconsistent across studies. In fact, some studies have reported an increase in muscle protein synthesis after T administration (24), whereas others have reported inhibition of muscle protein degradation (25, 26). The rapid loss of skeletal muscle mass after induction of androgen deprivation in men with prostate cancer suggests that increased muscle protein degradation may be involved. Indeed, in preclinical models, T administration blocks the rapid muscle atrophy and protein degradation induced by glucocorticoids or castration, by activating the Akt pathway (27–30), and by increasing intramuscular IGF-I gene expression (31). Recently, it has been shown that castration reduces Akt/mTOR signaling independent of AMPK signaling in the gastrocnemius muscle of the mouse (32) and that the selective activation of the estrogen receptor (ER)β increases skeletal muscle mass and intramuscular IGF-I expression independently of the androgenic signaling in castrated mice (33).

We used orchiectomized (Cx) mice to mimic closely the state of severe androgen deprivation observed in men with prostate cancer after administration of blockers of androgen synthesis or action. We examined the changes in the UPS and ALP signaling after Cx with and without T and hydroxyflutamide (Flut) administration in the levator ani muscle that underwent rapid and profound loss of mass (high androgen responder) and in the triceps muscle (low androgen responder) that underwent slower and less profound loss of muscle mass than the levator ani.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Two-month-old, sexually mature, C57Bl/6J male mice were used. Mice were randomly assigned to 3 experimental groups: intact (eugonadal), sham-operated (sham) mice treated with corn oil (vehicle); Cx mice treated with the vehicle; and Cx mice treated with T propionate (Cx T) in corn oil, n = 4–5/group. Seven days after castration, Cx mice were supplemented sc with 3 mg/(kg × d) T for 7 days (Cx 7d/T3 7d) or 43 days (Cx 7d/T3 43d). Treatments at 0.1 (Cx 7d/T0.1 7d) and 0.8 mg/(kg × d) T (Cx 7d/T0.8 7d) were additionally used for 7 days in the time-course experiment. Sham-operated mice and mice Cx for 14 days (Cx 14d) or 50 days (Cx 50d) injected with vehicle alone served as controls. Flut (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at 5 mg/(kg × d) for 7 days (Cx 7d/T3 7d/Flut 7d).

Mice were castrated aseptically under anesthesia through a midline incision of the scrotum to remove testes. Animals were kept on a 12-hour light, 12-hour dark cycle and given food and water ad libitum, according with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Boston University.

Western blotting and antibodies

Muscles were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (31), and protein concentration was measured using the BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology). Proteins (20–30 μg) were separated in 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare). Membranes were blocked in Tris-0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) 5% milk and incubated at 4°C with primary antibodies in 5% BSA/TBS-T. Secondary antibodies were incubated in 5% milk TBS-T. Enzymatic chemiluminescence (ECL) (GE Healthcare) was used to impress X-Omat films (Kodak), and FluorChem-SP Imaging System (Alpha Innotech) was used for band densitometry.

Primary antibodies were as following. 1) Rabbit polyclonal to: phospho-mTORSer2448, mTOR, phospho-tuberous sclerosis complex protein 2 (TSC2)Ser1387, phospho-TSC2Thr1462, TSC2, phospho-RaptorSer792, regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (Raptor), phospho-AMPKαThr172, AMPKα, phospho-FoxO1Ser256, FoxO1, phospho-FoxO3ASer318/321, FoxO3A, phospho-FoxO4Ser262, FoxO4, and LC3B (Cell Signaling Technology). And 2) goat polyclonal to peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor β/δ (PPARβ/δ) and mouse monoclonal to β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc).

Secondary antibodies were as following. Goat polyclonal antimouse or antirabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and donkey polyclonal antigoat IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz Technology, Inc); and goat antirabbit IgG-HRP (Cell Signaling Technology).

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

RNA isolation, c-DNA synthesis and quantitative PCR (qPCR) were carried out as previously shown (31). Reactions were normalized for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene expression. The list of the primers used is reported in Supplemental Table 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org.

Proteasome and cathepsin L activity assay

20S Proteasome Activity Assay kit (Millipore) was used to quantify proteasome enzymatic activity. Frozen samples (20–30 mg) were lysed in 8-mL/g tissue of a solution composed by 150mM NaCl, 50mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 5mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100, by rotating the tubes at 4°C for 30 minutes, with vortexing every 10 minutes. The lysate was centrifuged at 4°C for 10 minutes at 10 000 rpm. The soluble fraction was collected, and its protein concentration was determined using the BCA method (Pierce Biotechnology). The chymotrypsin activity was measured at 37°C, by detecting the fluorophore 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin, after cleavage of the proteasome labeled substrate Suc-LLVY-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (50μM).

Cathepsin L Activity Fluorometric Assay kit (Abcam) was used to quantify lysosome activity. Frozen samples (20–30 mg) were pulverized as above and then lysed in the lysis buffer provided by the manufacturer. Samples were incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes, mixed every 10 minutes, and then centrifuged at 4°C for 10 minutes at 10 000 rpm. Protein concentration of the soluble fraction was determined as above. The cathepsin L activity was measured at 37°C, using the preferred cathepsin L substrate sequence FR conjugated with the amino-4-trifluoromethyl coumarin (0.2mM final concentration) provided with the kit.

For both assays, the fluorescence was monitored for 2 hours at 380/460 nm (20S proteasome) and at 400/505 nm (cathepsin L) in a 96-well plate, using a microplate reader (Tecan). Background fluorescence, including substrate, was subtracted from sample measurements.

Statistical analysis

Results shown are means ± SEM. One-way ANOVA was used in experiments with more than 2 independent groups. If overall ANOVA revealed significant difference, Student's t test was used to analyze differences between groups. The results were considered significant if the null hypothesis could not be rejected at P ≤ .05.

Results

Castration increases and T inhibits proteasome activity in the levator ani muscle

For the short-term experiment, the mice were castrated and 7 days after castration, treated with T or vehicle alone for 7 additional days (Figure 1A). As expected, the levator ani muscle of vehicle-treated castrated mice had substantially lower mass than that of T-treated castrated mice (Figure 1B). The rapid changes in levator ani muscle mass of castrated mice were associated with significantly reduced androgen receptor (AR) protein level (Figure 1, C and D), and with higher levels of the 20S proteasome enzymatic activity (Figure 1E). The MuRF1 and MAFbx expression levels were also significantly higher in castrated mice (Figure 1F), as well as the gene expression of the 19S proteasome subunits, proteasome subunit β type 10 and proteasome 28 subunit β (Supplemental Figure 1), and of the 20S proteasome subunits, proteasome subunit α type 6 and proteasome 26S subunit, non-ATPase, 4 (Supplemental Figure 2). T supplementation rescued all of the castration-associated changes described above.

Figure 1.

Castration is associated with loss of muscle mass and increased proteasome enzymatic activity in the levator ani muscle. (A) The mice were Cx and treated after 7 days with either vehicle or 3 mg/(kg × d) T (T3) for an additional 7 days. Sham-operated mice served as controls. (B) Castration for 7 or 14 days reduced levator ani (LA) muscle mass, decreased AR protein level (C and D), and induced 20S proteasome enzymatic activity (E) and MuRF1 and MAFbx mRNA expression measured by qPCR (F). T administration restored these changes to that seen in sham-operated mice. Results are mean ± SEM; n = 4–5/group. *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001 vs sham mice; #, P < .05; ##, P < .01 vs Cx 7d mice; ^, P < .05; ^^^, P < .001 vs Cx 14d mice. Cx 7d, mice castrated for 7 days; Cx 14d, mice castrated for 14 days; Cx7d/ T 7d, mice castrated for 7 days and then treated with T for 7 days starting on day 8.

Castration increases and T inhibits lysosome activity in the levator ani muscle

To further investigate the cause of the rapid loss of levator ani muscle mass after short-term castration, we quantitated autophagy. Relative to the sham controls, the castrated mice showed consistent induction of the enzymatic activity of cathepsin L, one of the main lysosome proteases (Figure 2A), and increased expression of key markers of ALP (LC3B, cathepsin L, Bnip3, and Beclin) (Figure 2, B and C) and lysosome biogenesis (Klf15 and transcription factor EB [Tfeb]) (Figure 2D) (9, 34). We assessed then autophagy activation by measuring the level of LC3B. The LC3B protein is a part of the autophagosome during the engulfment of cellular components in the early steps of autophagy. The conjugation of the unconjugated LC3B, conventionally named LC3BI, to the phosphatidyl-ethanolamine of the vacuolar membrane of the autophagosome to generate the LC3BII marks autophagy activation (35). Castrated mice showed increased levels of LC3BII, LC3BI, and LC3BII to LC3BI ratio (Figure 2, E–G), indicating autophagy activation. T supplementation attenuated or prevented the castration-associated increase in cathepsin L activity as well as reduced to control levels the expression and/or the activation of the other markers of autophagy.

Figure 2.

Castration is associated with increased cathepsin L activity along with increased expression levels and activity of ALP markers in the levator ani muscle. (A) Cathepsin L enzymatic activity. mRNA expression level was measured using qPCR for LC3B and cathepsin L (B), Bnip3 and Beclin1 (C), and Klf15 and Tfeb (D). Castration increased the level of LC3BI (E and F) and LC3BII (E) as well as increased the ratio of LC3BII to LC3BI (G). Results are mean ± SEM; n = 4–5/group. *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001 vs sham mice; #, P < .05; ##, P < .01; ###, P < .001 vs Cx 7d mice; ^, P < .05; ^^, P < .01; ^^^, P < .001 vs Cx 14d mice.

Castration increases FoxO3 activation in the levator ani muscle

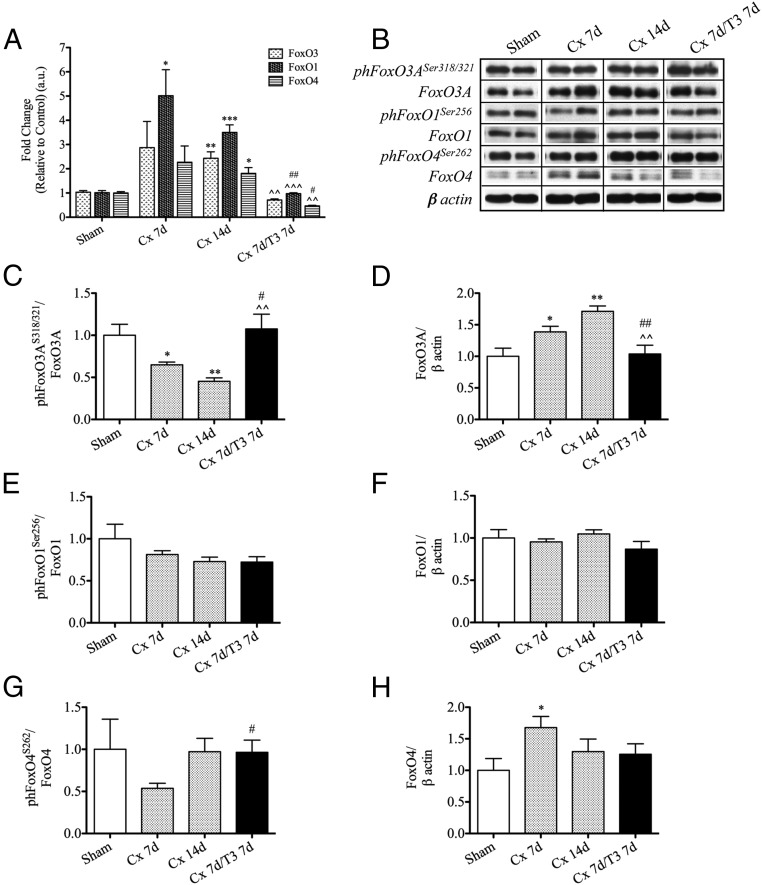

FoxO1, FoxO3, and FoxO4 play an important role in UPS and ALP induction during muscle atrophy (8, 13, 36). Castrated mice showed significantly higher mRNA levels of FoxO1, FoxO3, and FoxO4 compared with controls (Figure 3A), indicating a transcriptional control by T on these genes. Castration reduced the level of FoxO3A phosphorylation at serine 318 and 321, both targets of Akt activity, and increased its total content (Figure 3, B–D), indicating that T deprivation activates FoxO3A. Although FoxO1 level did not change after castration or after T supplementation (Figure 3, B, E, and F), the changes of FoxO4 level and phosphorylation 7 days after castration showed a trend somewhat comparable with that in FoxO3A (Figure 3, B, G, and H). T treatment normalized the castration-associated changes in the expression and activity of FoxO3.

Figure 3.

Effect of castration and T supplementation on FoxOs gene expression and activation in the levator ani muscle. Increased mRNA level of FoxO1, FoxO3, and FoxO4 (A) assessed by qPCR. Decreased phosphorylation of FoxO3A on serine 318/321 and increased level of total FoxO3A (B–D) measured by Western blotting. There were no significant changes in total and serine 256 phosphorylation of FoxO1 (B, E, and F). The changes in total FoxO4 protein level were inconsistent in castrated mice (B, G, and H). Results are mean ± SEM; n = 4–5/group. *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001 vs sham mice; #, P < .05; ##, P < .01 vs Cx 7d mice; ^^, P < .01; ^^^, P < .001 vs Cx 14d mice.

The loss of levator ani muscle mass after castration is associated with mTOR inhibition

Because IGF-I, a mediator of the anabolic effect of T on the muscle (31, 37), regulates mTOR activity (15), and because mTOR is a major regulator of protein synthesis and lysosome activity (38), we determined whether androgen deprivation and supplementation affect mTOR activation. Castration reduced mTOR activation, as shown by the decreased phosphorylation on serine 2448 (Figure 4, A and B). Additionally, castration reduced the phosphorylation of 2 downstream targets of mTOR, the ribosomal protein S6 kinase polypeptide 1 and the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (data not shown). We then analyzed the level and the activation of 2 key mTOR regulators, TSC2 and Raptor (38). In normal conditions, TSC2 inhibits mTOR by inducing the GTPase activity of Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb), an essential activator of mTOR (15). Conversely, the anabolic stimuli prevent mTOR inhibition, by inducing the Akt-mediated TSC2 phosphorylation, eg, on serine 1462 (39). Castration strongly increased TSC2 protein level and gene expression (Figure 4, A, C, and D) and significantly reduced TSC2 phosphorylation on serine 1462 (Figure 4, A and E). T supplementation rescued these changes, indicating that T sustains mTOR activity by reducing TSC2 level. Because AMPK inhibits mTOR activity by phosphorylating TSC2 on serine 1387 (40) and Raptor on serine 792 (20), we investigated whether mTOR was also inhibited by AMPK in our experimental model. Castration significantly increased phospho-RaptorSer792 level (Figure 4, A and F). There also was a modest, statistically insignificant, increase in phospho-TSC2Ser1387 (Figure 4, A and G).

Figure 4.

T deprivation is associated with mTOR inhibition in the levator ani muscle. Western blotting showing reduced mTOR activation (A and B), increased level of total TSC2 (A and C), reduced Akt-dependent TSC2 phosphorylation on serine 1462 (A and E), increased AMPKα-dependent Raptor phosphorylation on serine 792 (A and F), and numerical increase in AMPKα-dependent TSC2 phosphorylation on serine 1387 (A and G) in castrated mice. (D) qPCR showing mRNA expression level of TSC2. Results are mean ± SEM; n = 4–5/group. **P < .01; ***P < .001 vs sham mice; #, P < .05; ###, P < .001 vs Cx 7d mice; ^, P < .05; ^^, P < .01; ^^^, P < .001 vs Cx 14d mice.

Castration induces AMPKα activation in the levator ani muscle

AMPK activation leads to myotube atrophy in vitro (41), to muscle fiber remodeling in vivo (42), and to increased muscle MuRF1 and MAFbx gene expression and autophagy (18, 22, 23). The castrated mice showed strong activation of AMPKα, assessed using an antibody that recognizes AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 when phosphorylated on threonine 172 (Figure 5, A and B), as well as increased expression of liver kinase B1 (Lkb1), the main AMPK-activating kinase (Figure 5C) (43). We further evaluated the level of PPARδ, which has been involved in muscle AMPKα activation in response to voluntary exercise and starvation (44). Castration induced PPARδ mRNA expression, protein accumulation, and activity, as shown by the increased expression of one of its targets, the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isozyme 4 (Pdk4) gene (Figure 5, D and E) (44). T reversed these changes to those seen in control mice.

Figure 5.

Castration activates AMPKα and PPARδ in the levator ani muscle. Castration was associated with increased AMPKα phosphorylation on threonine 172 (A and B), increased Lkb1 gene expression (C), and increased PPARδ protein (A and D) and mRNA (E) content and Pdk4 gene expression (E). Results are mean ± SEM; n = 4–5/group. *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001 vs sham mice; ##, P < .01; ###, P < .001 vs Cx 7d mice; ^^, P < .01; ^^^, P < .001 vs Cx 14d mice.

Long-term castration induces lysosome activity in the triceps muscle

To further corroborate our data on the high androgen responder muscle levator ani, we investigated the effect of T deprivation and supplementation in the low androgen responder muscle triceps. Seven days after castration, the triceps muscle showed significant induction of MuRF1 and MAFbx gene expression (Supplemental Figure 3) but no significant change in its mass or in the proteasome enzymatic activity (data not shown). We reasoned that long-term castration is necessary to evaluate properly the effect of castration on UPS and ALP in the triceps muscle. Mice were castrated and after 7 days supplemented with either the vehicle or T for 43 days (Figure 6A). The triceps muscle of mice castrated for 50 days showed significant loss of mass (Figure 6B) but, surprisingly, no increase in proteasome enzymatic activity (Figure 6C); the expression levels of MuRF1 and MAFbx were in fact lower in castrated mice compared with controls (Figure 6D). Nevertheless, we found higher proteasome subunit β type 10, proteasome 28 subunit β, proteasome subunit α type 6, and proteasome 26S subunit, non-ATPase, 4 gene expression in castrated mice (Supplemental Figures 4 and 5). Castration was associated with enhanced rate of autophagy, as shown by the high cathepsin L activity (Figure 6E), by the increased LC3B, cathepsin L, Bnip3, Beclin1, Klf15, and Tfeb gene expression (Figure 6, F–H), and by the increased level and activation of LC3B (Figure 6, I–K). T returned several of these values to control level.

Figure 6.

Castration is associated with loss of muscle mass and increased cathepsin L enzymatic activity in the triceps muscle. (A) The mice were Cx on day 0 and treated 7 days after castration with either vehicle or T for an additional 43 days. Castration reduced triceps muscle mass (B) but did not induce proteasome activity (C). (D) qPCR for MuRF1 and MAFbx. Castration induced cathepsin L activity (E) and increased LC3B, cathepsin L, Klf15, and Tfeb (F and H), but not Bnip3 and Beclin1 (G), gene expression. LC3B level measured by Western blotting (I–K). Results are mean ± SEM; n = 4–5/group. *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001 vs sham mice; ^, P < .05; ^^, P < .01; ^^^, P < .001 vs Cx mice.

Castration is associated with FoxO3 activation, mTOR inhibition, and AMPKα activation in the triceps muscle

Similar to what is shown in the levator ani muscle after short-term castration, the triceps muscle of long-term castrated mice showed major increments in FoxO1, FoxO3, and FoxO4 gene expression (Figure 7A), significant changes in FoxO3A protein level and activation (Figure 7, B–D), and a comparable, albeit not statistically significant, trend for both FoxO1 and FoxO4 (Figure 7, B and E–H). T treatment rescued these changes. The triceps muscle of castrated mice did not show a decline in mTOR activation (Figure 8, A and B). However, as in the levator ani at short term, we found reduced Akt-mediated phosphorylation of TSC2 and increased TSC2 level (Figure 8, A and C–E). In addition, T deprivation increased AMPKα-mediated phosphorylation of TSC2 and Raptor (Figure 8, A, F, and G) and induced AMPKα activation (Figure 8, H and I) and Lkb1 gene expression (Figure 8L). T treatment rescued all these changes and even reduced AMPKα activation and Lkb1 expression below controls (Figure 8, H–L). However, unlike the levator ani muscle, the triceps muscle of castrated mice showed reduced mRNA expression level of PPARδ and Pdk4 and increased PPARδ protein level in T-treated mice (Figure 8, H and K, and Supplemental Figure 6).

Figure 7.

Castration activates FoxO3 in the triceps muscle. T deprivation significantly increased FoxO1, FoxO3, and FoxO4 gene expression (A) and activated FoxO3A (B–D). Castrated mice showed a trend of induction of both FoxO1 and FoxO4 (B and E–H). Results are mean ± SEM; n = 4–5/group. *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001 vs sham mice; ^, P < .05; ^^, P < .01; ^^^, P < .001 vs Cx mice.

Figure 8.

Castration inhibits mTOR and activates AMPK in the triceps muscle. (A and B) Western blotting for mTOR. Castration increased TSC2 activation and level (A, C, and D) but did not change significantly the AMPKα-dependent phosphorylation of TSC2 (F). (E) qPCR of TSC2. T deprivation induced Raptor inhibition by AMPKα (A and G). (H and I) Western blotting showing that castration induces, and T represses, AMPKα activation. (J) qPCR of Lkb1. (K) Castration reduced, and T increased, PPARδ protein level. Results are mean ± SEM; n = 4–5/group. *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001 vs sham mice; ^, P < .05; ^^, P < .01; ^^^, P < .001 vs Cx mice.

The T/AR axis is essential to inhibit UPS and ALP pathways

To further corroborate our data, we treated castrated mice with 3 different doses of T (0.1, 0.8, and 3 mg/[kg × d]) and with the selective AR inhibitor Flut at short term. In castrated mice, T treatment rescued dose dependently the levator ani mass and the expression and activation of UPS and ALP markers (eg, LC3B), an effect prevented by Flut, as well as the induction of TSC2 and the activation of AMPKα (Supplemental Figures 7–16). We then quantified by qPCR the expression of AR, of the ornithine decarboxylase 1 (Odc1), an AR target on muscle satellite cells (45), and of members of the IGF-I signaling. The levator ani of castrated mice treated with vehicle or low T showed increased expression of AR, decreased expression of Odc1 and Igf1-Ea, the muscle-specific IGF-I (31), and increased expression of growth factor receptor-bound protein 10 (Grb10), an inhibitor of the IGF-I receptor (Supplemental Figure 17). T rescued these changes dose dependently, whereas Flut blocked the Igf1-Ea rescue by T (Supplemental Figures 17 and 19). Triceps muscle of mice castrated at long term showed reduced AR, Odc1, and Igf1-Ea expression and increased Grb10 expression (Supplemental Figure 18). Finally, because ERβ regulates muscle growth in castrated rats (33), and because T is aromatized to β-estradiol (46), we further investigated the role of the estrogen pathway in our model. Both muscles showed induction of ERα and reduction of ERβ expression upon castration as well as increased expression of gluthatione peroxidase 3 and reduced level of pyruvate carboxylase (47), 2 ERα/β targets in the muscle (Supplemental Figures 20 and 21). T rescued these changes.

Discussion

Skeletal muscle homeostasis results from a balance between growth-promoting and atrophy-promoting stimuli. ADT in men with metastatic prostate cancer results in loss of muscle mass and increased risk of frailty and functional limitations (1, 2, 48). Our study emphasizes the role of T in regulating muscle mass and homeostasis through inhibition of muscle protein degradation pathways in states of severe androgen deficiency (28–30, 49–51). The prevalent view is that T augments muscle mass by increasing muscle protein synthesis and improving the reutilization of amino acids. However, the changes in muscle protein synthesis upon T administration have been inconsistent across studies (51–53). Indeed, in humans, although muscle protein synthesis was transiently stimulated after short-term T administration (24), the net gain in muscle mass after 6 months of treatment was associated with inhibition of muscle protein degradation but no change in muscle protein synthesis (52), suggesting a direct involvement of androgens in regulating muscle protein degradation.

Here, we show that, in both the high androgen responder muscle, levator ani, and in the low androgen responder muscle, triceps, T deprivation induces loss of muscle mass in association with the activation of autophagy mediated by FoxOs and Tfeb (8, 34, 54, 55), suggesting that AR inhibits FoxOs and Tfeb gene promoters. The remarkably rapid loss of mass in the levator ani muscle was associated with a striking increase in UPS activity and in the expression of MuRF1 and MAFbx. However, in the triceps muscle, the changes in proteasome activity after long-term castration were not consistent. Unexpectedly, MuRF1 and MAFbx gene expression in the triceps muscle of the long-term castrated mice was lower than controls, as also reported by others (51), suggesting the achievement of a new equilibrium after a time point after castration in which the proteasome enzymatic activity was at its peak. Thus, our data suggest that the proteasome may be more active in the early phases after castration, especially in the levator ani, whereas increased autophagy remains evident after both short- and long-term androgen deprivation in both muscles.

In this study, we found also the modulation of the activities of mTOR, the main nutrient sensor of the cell, and AMPK, the main energy sensor of the cell, by T. Previous studies have clarified the opposing actions of mTOR and AMPK on muscle homeostasis. For example, mTOR and Raptor-null mice are characterized by reduced muscle mass and reduced activation of AMPK (56, 57). In contrast, the absence of AMPKα1 results in muscle hypertrophy, in vitro and in vivo, due to chronic mTOR activation (19, 21). These data indicate that mTOR and AMPK are cross-balancing pathways in physiologic conditions, the former boosts muscle growth, and the latter limits muscle hypertrophy (58). Here, we found that castration reduced mTOR activity in the levator ani and in the triceps muscle, as shown previously in the gastrocnemius muscle (32). We show also that castration induces the overexpression of TSC2 and the lower Akt-mediated inhibition of TSC2. In addition, both levator ani and triceps muscle of castrated mice showed consistent AMPKα activation, as indicated also by the increased phosphorylation of Raptor (20), in contrast to what has been reported in the gastrocnemius muscle (32). The reason of this discrepancy is unknown but might be related to the different level of AR in these muscles. Therefore, in the levator ani and triceps muscle of castrated mice, AMPK seems to inhibit mTOR by phosphorylating Raptor more than TSC2, in agreement with the evidence that AMPK restrains mTOR activity in TSC2-null cells (20). Moreover, our finding that the levator ani muscle of castrated mice shows increased level and activity of PPARδ is in agreement with the evidence that the pharmacological induction of PPARδ turns on AMPKα (44). Finally, the reduced Akt-mediated inhibitory phosphorylation of TSC2 on serine 1462, and the evidence that both the levator ani and triceps muscle of castrated mice showed reduced Igf1-Ea expression and increased Grb10 expression, further confirms the main role of IGF-I in the anabolic effect of androgens on the muscle (31, 37).

The branched chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine, and valine) positively regulate mTOR. The effects of branched chain amino acids on mTOR are controlled on the surface of lysosomes, where mTOR binds Rheb (17, 59). Thus, the anabolic stimuli that positively regulate mTOR via Rheb are integrated with the stimuli released by amino acid availability, to fine tune protein synthesis and autophagy (15). mTOR leads also to the reformation of lysosomes during starvation, indicating that the amino acids released by lysosomal digestion regulate mTOR when the nutrient supply is limiting (15, 60). In our study, castration reduced and T increased mTOR activity. It has been shown recently that castrated rats do not increase muscle protein synthesis in response to leucine administration (51). Therefore, it is possible that castration is associated with the loss of key anabolic inputs that regulate protein synthesis (51), leaving the autophagy activity without a negative break. Our findings on TSC2/Raptor and autophagy in the muscle of castrated mice are consistent with this hypothesis and might explain the rapid loss of the levator ani muscle mass. Thus, we hypothesize that T down-regulates AMPK to preserve mTOR activity and inhibit lysosomal activity and thereby tilt the homeostatic balance in favor of muscle fiber hypertrophy, the main anabolic effect of T on the muscle (Supplemental Figure 22). We propose that severe androgen deprivation, such as that observed after the institution of ADT in men with prostate cancer, changes the balance between AMPK and mTOR activity and results in muscle loss by inducing autophagy and proteasome pathways.

We further emphasized the role of the T/AR axis in the regulation of ALP and mTOR pathways in the levator ani muscle by showing, for example, the T dose-dependent inhibition of LC3B activation and TSC2 accumulation (Supplemental Figures 12–15) and the effect of Flut in the T-dependent rescue of levator ani muscle mass (Supplemental Figure 7). In addition, the effect of T on Odc1 expression in the triceps muscle of castrated mice (Supplemental Figure 18) suggests the involvement of the satellite cells in the rescue of the triceps muscle mass at long term (45). Castration was also associated with changes in ERα/β expression, as well as with gluthatione peroxidase 3 and pyruvate carboxylase gene expression (Supplemental Figures 20 and 21), indicating a role for estrogens in T action. However, because in humans only a negligible percentage of T is aromatized in β-estradiol (46), we do not believe that estrogens play a major role in the anabolic action of T on the muscle of castrated mice.

Further experiments using specific AMPKα1 and Lkb1-inducible knockout mouse models in the skeletal muscle are necessary to confirm our hypotheses. Moreover, the use of pharmacological inhibitors of AMPK and mTOR in castrated mice treated with and without T will better define the role that AMPKα and mTOR play in mediating the anabolic action of androgens on the muscle. In addition, it is possible that the differences in the level of AR and AR coactivators between high and low androgen responder muscles (61) may contribute to the different responsiveness to T in our model. The ability of T to inhibit UPS and ALP, and to modulate key metabolic pathways, supports the potential application of androgens to mitigate muscle wasting. In addition, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms that drive rapid muscle loss after androgen deprivation will facilitate the development of new pharmacological treatments to treat muscle wasting and functional limitations in patients who are receiving ADT.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Medicine and the Evans Medical Foundation of the Boston University Bridge Funding and the Clinical and Translational Science Institute Grants UL1RR025771 and UL1TR000157 (to C.S. and R.J.), and the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute on Aging Grant 5R01AG070534–07 (to S.B.), and the Boston Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center Grant 5P30AG031679 (to C.S. and S.B.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ADT

- androgen deprivation therapy

- ALP

- autophagy/lysosome pathway

- AMPK

- 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase

- AR

- androgen receptor

- Bnip3

- BCL2/adenovirus E1b-interacting protein 3

- Cx

- orchiectomy

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- Flut

- hydroxyflutamide

- FoxO

- forkhead box protein O

- Grb10

- growth factor receptor-bound protein 10

- HRP

- horseradish peroxidase

- Klf15

- Kruppel-like factor 15

- LC3B

- microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3β

- Lkb1

- liver kinase B1

- MAFbx

- muscle atrophy F-box

- mTOR

- mechanistic target of rapamicyn

- MuRF1

- muscle ring finger1

- Odc1

- ornithine decarboxylase 1

- Pdk4

- pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isozyme 4

- PPARβ/δ

- peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor β/δ

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- Raptor

- regulatory-associated protein of mTOR

- Rheb

- Ras homolog enriched in brain

- TBS-T

- Tris-0.1% Tween 20

- Tfeb

- transcription factor EB

- TSC2

- tuberous sclerosis complex protein 2

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- UPS

- Ub-proteasome system.

References

- 1. Maggio M, Basaria S. Welcoming low testosterone as a cardiovascular risk factor. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21:261–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Basaria S, Muller DC, Carducci MA, Egan J, Dobs AS. Hyperglycemia and insulin resistance in men with prostate carcinoma who receive androgen-deprivation therapy. Cancer. 2006;106:581–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Biolo G, Maggi SP, Williams BD, Tipton KD, Wolfe RR. Increased rates of muscle protein turnover and amino acid transport after resistance exercise in humans. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:E514–E520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Medina R, Wing SS, Goldberg AL. Increase in levels of polyubiquitin and proteasome mRNA in skeletal muscle during starvation and denervation atrophy. Biochem J. 1995;307:631–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thomason DB, Booth FW. Atrophy of the soleus muscle by hindlimb unweighting. J Appl Physiol. 1990;68:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bodine SC, Latres E, Baumhueter S, et al. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science. 2001;294:1704–1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gomes MD, Lecker SH, Jagoe RT, Navon A, Goldberg AL. Atrogin-1, a muscle-specific F-box protein highly expressed during muscle atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14440–14445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sandri M, Sandri C, Gilbert A, et al. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell. 2004;117:399–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shimizu N, Yoshikawa N, Ito N, et al. Crosstalk between glucocorticoid receptor and nutritional sensor mTOR in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2011;13:170–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sacheck JM, Ohtsuka A, McLary SC, Goldberg AL. IGF-I stimulates muscle growth by suppressing protein breakdown and expression of atrophy-related ubiquitin ligases, atrogin-1 and MuRF1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E591–E601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sandri M. Autophagy in skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1411–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mammucari C, Milan G, Romanello V, et al. FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab. 2007;6:458–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao J, Brault JJ, Schild A, et al. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 2007;6:472–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bodine SC, Stitt TN, Gonzalez M, et al. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1014–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Efeyan A, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM. Amino acids and mTORC1: from lysosomes to disease. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:524–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zoncu R, Bar-Peled L, Efeyan A, Wang S, Sancak Y, Sabatini DM. mTORC1 senses lysosomal amino acids through an inside-out mechanism that requires the vacuolar H(+)-ATPase. Science. 2011;334:678–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sancak Y, Bar-Peled L, Zoncu R, Markhard AL, Nada S, Sabatini DM. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell. 2010;141:290–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 2011;331:456–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mounier R, Lantier L, Leclerc J, et al. Important role for AMPKα1 in limiting skeletal muscle cell hypertrophy. FASEB J. 2009;23:2264–2273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30:214–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lantier L, Mounier R, Leclerc J, Pende M, Foretz M, Viollet B. Coordinated maintenance of muscle cell size control by AMP-activated protein kinase. FASEB J. 2010;24:3555–3561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Krawiec BJ, Nystrom GJ, Frost RA, Jefferson LS, Lang CH. AMP-activated protein kinase agonists increase mRNA content of the muscle-specific ubiquitin ligases MAFbx and MuRF1 in C2C12 cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1555–E1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sanchez AM, Csibi A, Raibon A, et al. AMPK promotes skeletal muscle autophagy through activation of forkhead FoxO3a and interaction with Ulk1. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:695–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferrando AA, Tipton KD, Doyle D, Phillips SM, Cortiella J, Wolfe RR. Testosterone injection stimulates net protein synthesis but not tissue amino acid transport. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:E864–E871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Axell AM, MacLean HE, Plant DR, et al. Continuous testosterone administration prevents skeletal muscle atrophy and enhances resistance to fatigue in orchidectomized male mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E506–E516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bhasin S, Storer TW, Berman N, et al. The effects of supraphysiologic doses of testosterone on muscle size and strength in normal men. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reid IR, Wattie DJ, Evans MC, Stapleton JP. Testosterone therapy in glucocorticoid-treated men. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1173–1177 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pires-Oliveira M, Maragno AL, Parreiras-e-Silva LT, Chiavegatti T, Gomes MD, Godinho RO. Testosterone represses ubiquitin ligases atrogin-1 and Murf-1 expression in an androgen-sensitive rat skeletal muscle in vivo. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ibebunjo C, Eash JK, Li C, Ma Q, Glass DJ. Voluntary running, skeletal muscle gene expression, and signaling inversely regulated by orchidectomy and testosterone replacement. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E327–E340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao W, Pan J, Zhao Z, Wu Y, Bauman WA, Cardozo CP. Testosterone protects against dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy, protein degradation and MAFbx upregulation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;110:125–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Serra C, Bhasin S, Tangherlini F, et al. The role of GH and IGF-I in mediating anabolic effects of testosterone on androgen-responsive muscle. Endocrinology. 2011;152:193–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. White JP, Gao S, Puppa MJ, Sato S, Welle SL, Carson JA. Testosterone regulation of Akt/mTORC1/FoxO3a signaling in skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;365:174–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Velders M, Schleipen B, Fritzemeier KH, Zierau O, Diel P. Selective estrogen receptor-β activation stimulates skeletal muscle growth and regeneration. FASEB J. 2012;26:1909–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Settembre C, Di Malta C, Polito VA, et al. TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science. 2011;332:1429–1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barth S, Glick D, Macleod KF. Autophagy: assays and artifacts. J Pathol. 2010;221:117–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reed SA, Sandesara PB, Senf SM, Judge AR. Inhibition of FoxO transcriptional activity prevents muscle fiber atrophy during cachexia and induces hypertrophy. FASEB J. 2012;26:987–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lewis MI, Horvitz GD, Clemmons DR, Fournier M. Role of IGF-I and IGF-binding proteins within diaphragm muscle in modulating the effects of nandrolone. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;282:E483–E490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:21–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis complex-2 tumor suppressor gene product tuberin as a target of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/akt pathway. Mol Cell. 2002;10:151–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tong JF, Yan X, Zhu MJ, Du M. AMP-activated protein kinase enhances the expression of muscle-specific ubiquitin ligases despite its activation of IGF-1/Akt signaling in C2C12 myotubes. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108:458–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Narkar VA, Downes M, Yu RT, et al. AMPK and PPARδ agonists are exercise mimetics. Cell. 2008;134:405–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mihaylova MM, Shaw RJ. The AMPK signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and metabolism. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1016–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lendoye E, Sibille B, Rousseau AS, Murdaca J, Grimaldi PA, Lopez P. PPARβ activation induces rapid changes of both AMPK subunit expression and AMPK activation in mouse skeletal muscle. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:1487–1498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee NK, Skinner JP, Zajac JD, MacLean HE. Ornithine decarboxylase is upregulated by the androgen receptor in skeletal muscle and regulates myoblast proliferation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E172–E179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. MacDonald PC, Madden JD, Brenner PF, Wilson JD, Siiteri PK. Origin of estrogen in normal men and in women with testicular feminization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979;49:905–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Baltgalvis KA, Greising SM, Warren GL, Lowe D. Estrogen regulates estrogen receptors and antioxidant gene expression in mouse skeletal muscle. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Basaria S, Lieb J, 2nd, Tang AM, et al. Long-term effects of androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2002;56:779–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wu Y, Bauman WA, Blitzer RD, Cardozo C. Testosterone-induced hypertrophy of L6 myoblasts is dependent upon Erk and mTOR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;400:679–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hourde C, Jagerschmidt C, Clement-Lacroix P, et al. Androgen replacement therapy improves function in male rat muscles independently of hypertrophy and activation of the Akt/mTOR pathway. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2009;195:471–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jiao Q, Pruznak AM, Huber D, Vary TC, Lang CH. Castration differentially alters basal and leucine-stimulated tissue protein synthesis in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E1222–E1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ferrando AA, Sheffield-Moore M, Yeckel CW, et al. Testosterone administration to older men improves muscle function: molecular and physiological mechanisms. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;282:E601–E607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Brodsky IG, Balagopal P, Nair KS. Effects of testosterone replacement on muscle mass and muscle protein synthesis in hypogonadal men–a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3469–3475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kamei Y, Miura S, Suzuki M, et al. Skeletal muscle FOXO1 (FKHR) transgenic mice have less skeletal muscle mass, down-regulated type I (slow twitch/red muscle) fiber genes, and impaired glycemic control. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41114–41123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sardiello M, Palmieri M, di Ronza A, et al. A gene network regulating lysosomal biogenesis and function. Science. 2009;325:473–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bentzinger CF, Romanino K, Cloëtta D, et al. Skeletal muscle-specific ablation of raptor, but not of rictor, causes metabolic changes and results in muscle dystrophy. Cell Metab. 2008;8:411–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Risson V, Mazelin L, Roceri M, et al. Muscle inactivation of mTOR causes metabolic and dystrophin defects leading to severe myopathy. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:859–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mounier R, Lantier L, Leclerc J, Sotiropoulos A, Foretz M, Viollet B. Antagonistic control of muscle cell size by AMPK and mTORC1. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2640–2646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Buerger C, DeVries B, Stambolic V. Localization of Rheb to the endomembrane is critical for its signaling function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:869–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yu L, McPhee CK, Zheng L, et al. Termination of autophagy and reformation of lysosomes regulated by mTOR. Nature. 2010;465:942–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Johansen JA, Breedlove SM, Jordan CL. Androgen receptor expression in the levator ani muscle of male mice. J Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19:823–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]