Abstract

The identification of precise mutations is required for a complete understanding of the underlying molecular and evolutionary mechanisms driving adaptive phenotypic change. Using plasticine models in the field, we show that the light coat color of deer mice that recently colonized the light-colored soil of the Nebraska Sand Hills provides a strong selective advantage against visually hunting predators. Color variation in an admixed population suggests that this light Sand Hills phenotype is composed of multiple traits. We identified distinct regions within the Agouti locus associated with each color trait and found that only haplotypes associated with light trait values have evidence of selection. Thus, local adaptation is the result of independent selection on many mutations within a single locus, each with a specific effect on an adaptive phenotype, thereby minimizing pleiotropic consequences.

Darwin believed that adaptation occurred through “slight successive variations” (1). Fisher later elaborated on this idea by proposing the geometric model of adaptation (2), which assumes that most mutations are pleiotropic and therefore that mutations of small phenotypic effect are more likely than those of large effect to bring a population closer to its fitness optimum. To test Fisher’s model, we must identify individual mutations and assess both their phenotypic effects and their degree of pleiotropy. Although recent years have seen considerable progress in identifying loci or genes underlying adaptive phenotypes [reviewed in (3, 4)], few have genetically dissected these loci to the level of individual mutations [but see (5-8)], and none have examined multiple traits at this level of resolution. Thus, it remains unclear whether genes that contribute to complex phenotypes (i.e., those composed of multiple traits) tend to do so through single pleiotropic mutations or multiple mutations with independent effects.

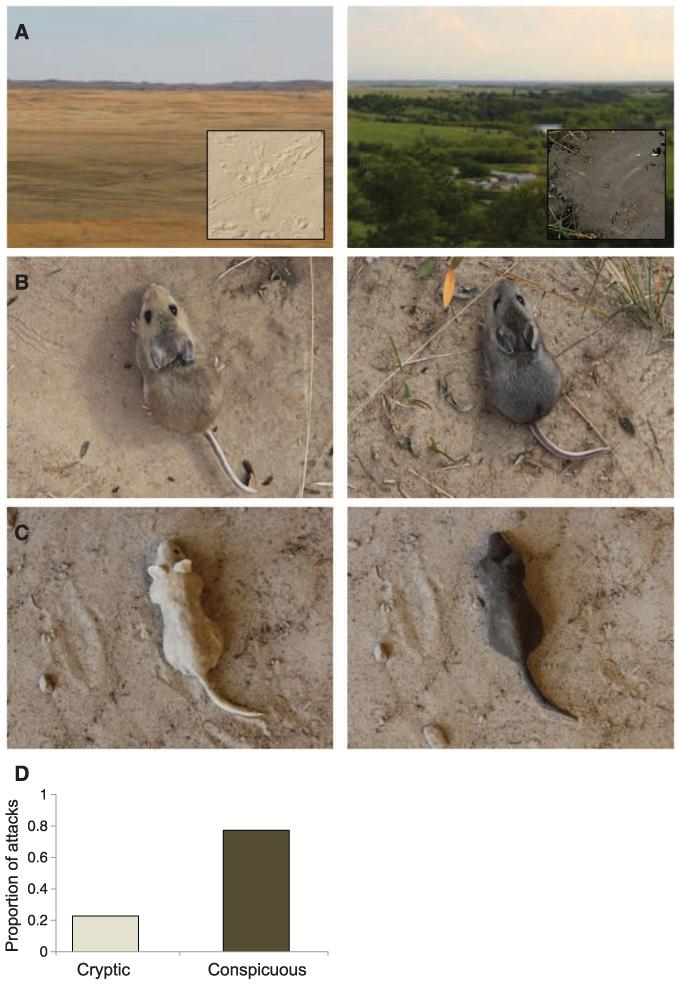

Deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) living on the light-colored soils of the Nebraska Sand Hills, a massive dune field formed only 8000 to 15,000 years ago (9), are lighter than conspecifics living on the surrounding dark soils (10, 11) (Fig. 1, A and B). To test the hypothesis that this light pelage is an adaptation for crypsis, we measured attack rates on light and dark plasticine mouse models (Fig. 1C) at multiple Sand Hills sites [following (12); also see (13)]. We found that conspicuous, dark models were attacked significantly more often than cryptic, light models (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1D). Together with previous experiments using avian predators and live mice (14), these results strongly suggest that the overall light color of Sand Hills mice is a recent adaptation driven, at least in part, by visually hunting predators.

Fig. 1.

Selective advantage of crypsis against predation. (A) Typical habitat in the Sand Hills (left) and the adjacent region (right). Insets show representative substrate from each habitat. (B) Typical mouse color phenotypes from on (left) and off (right) the Sand Hills, shown on light Sand Hills substrate. (C) Typical cryptic (left) and conspicuous (right) models, shown on Sand Hills substrate. (D) Proportion of predation events occurring over 2700 model nights in the Sand Hills habitat. Conspicuous models were attacked significantly more often than cryptic models (selection index = 0.545, χ2 = 6.546, df = 1, P = 0.011).

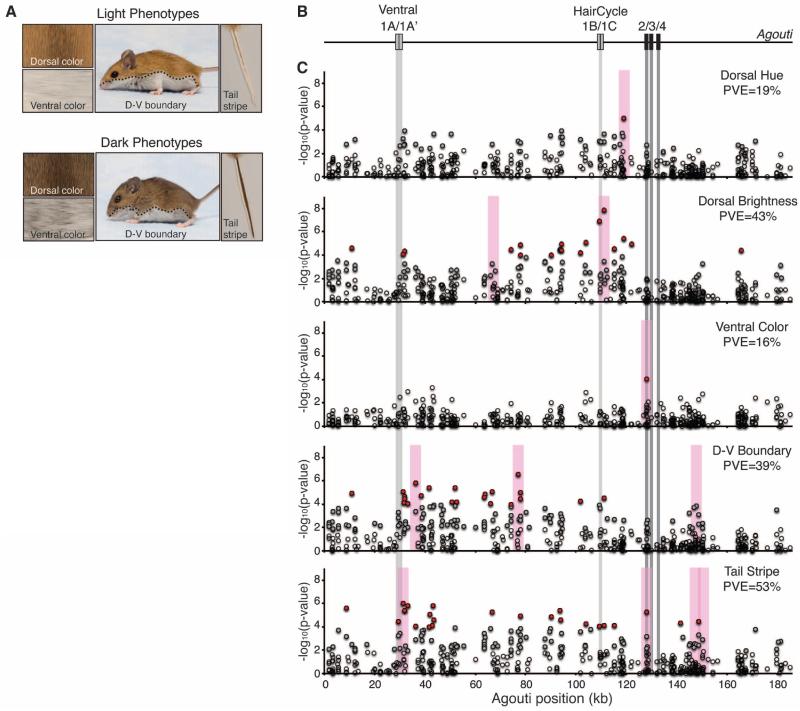

The light dorsal fur of Sand Hills mice is largely caused by a change at the Agouti locus. Specifically, a derived cis-acting increase in the duration and magnitude of Agouti expression during hair growth leads to a concomitant increase in the width of light pigmented bands on individual hairs (11). However, upon closer inspection of phenotypic variation, we found that Sand Hills and wild-type mice differ in multiple pigmentation traits that together give rise to the overall cryptic appearance of the Sand Hills mice (Fig. 2A). In addition to having a significantly lighter dorsum (one-tailed t test; N = 10 lab-reared mice; P = 8.2 × 10−4), Sand Hills mice also have a lighter ventrum, an upward shift in the dorsal-ventral (d-v) boundary, and a less pronounced tail stripe compared with the ancestral form (one-tailed t tests; N = 10 mice; ventral color: P = 3.9 × 10−5; d-v boundary: P = 1.4 × 10−4; tail stripe: P = 5.5 × 10−7). Because these derived light-color traits are all associated with Agouti in laboratory strains, they could be explained by either a single pleiotropic mutation of large effect or multiple mutations of smaller, more modular effect in this locus.

Fig. 2.

The light Sand Hills phenotype is composed of multiple traits, each mapping to different regions of Agouti. (A) Typical light and dark mice. Light mice have a brighter dorsum and ventrum, an upward shift in the d-v boundary, and a decrease in the width of the tail stripe. (B) Structure of the Agouti locus with coding exons (dark boxes) and untranslated exons (light boxes). (C) Genotype-phenotype association for 466 SNPs (circles) tested in 91 mice. SNPs significant after correcting for a false discovery rate (FDR) of 5% (gray circles) and after FDR and Bonferroni correction (red circles) are shown. Gray bars highlight the position of Agouti exons. Pink bars indicate the location of candidate SNPs for each trait (13). PVE by the candidate SNPs is given for each trait. All traits are significantly associated with variation in Agouti, and some traits map in or near known functional regions. Distinct patterns of association are observed for each trait.

To distinguish between these alternatives, we collected phenotypic (color and color pattern) and genotypic data from 91 wild-caught mice from a phenotypically diverse population located near the edge of the Sand Hills. We measured three color traits derived from a principal component analysis (PCA) of spectrophotometric data (dorsal hue, dorsal brightness, and ventral color) (table S1) and two color pattern traits (d-v boundary and tail stripe). Phenotypes in this wild population were largely independent (R2 range: 0.04 to 0.27) (table S2). In fact, several trait pairs lacked a significant correlation in spite of a large sample size (e.g., dorsal hue and d-v boundary, P = 0.69, N = 91 mice). These data suggest that these pigment traits are likely under independent genetic control.

To dissect the molecular basis of these traits, we combined a targeted enrichment strategy with next-generation sequencing [following (15)] to generate polymorphism data for ~2100 unlinked regions averaging 1.5 thousand base pairs (kbp) in length and a 185-kbp region containing Agouti and all known regulatory elements (Fig. 2B) (16). Using a genetic PCA on genome-wide polymorphism data (13), we identified four significant genetic principal components, none of which were associated with color (table S3). These data indicate that light and dark mice interbreed freely, and genetic structure is not associated with color variation in this population. Next, we examined linkage disequilibrium (LD) across Agouti (fig. S1) and found that the 95th percentile of r2 falls below 0.4 within 3 kbp (fig. S2). The extremely low level of LD is considerably less than reported for wild populations of Mus musculus (17); however, this is not surprising given the large effective population size we estimated for P. maniculatus (Ne > 50,000 mice) (13). Together, these data suggest that there has been sufficient recombination for fine-scale mapping color traits within Agouti.

To identify associations between these Agouti genotypes and color phenotypes, we used both single-SNP (single-nucleotide polymorphism) linear regressions and a multiple-SNP Bayesian approach (13, 18). Based on these analyses, we found each of the five color traits was statistically associated with a unique set of SNPs that together explained 16 to 53% of the variation (Fig. 2C and fig. S3). There was one exception: a serine deletion (ΔSer) in exon 2 was associated with both ventral color (P = 8.5 × 10−5) and tail stripe (P = 5.4 × 10−6). Notably, no single set of polymorphisms could account for variation across all five traits (table S4). These findings demonstrate that there are multiple mutations that contribute to different aspects of the light Sand Hills phenotype.

Additionally, several traits were associated with SNPs that fell in or near regions of known functional importance. Two Agouti isoforms under the control of different promoters have been identified: The ventral isoform containing noncoding exons 1A/1A′ is restricted to the ventral dermis and is required to establish the dorsal-ventral boundary during embryogenesis, and the hair-cycle-specific isoform containing noncoding exons 1B/1C is expressed in adults during hair growth and leads to the formation of light, pheomelanin bands on individual hairs (19, 20) (Fig. 2B). In our data, the d-v boundary and tail stripe traits mapped near the ventral promoter; dorsal brightness mapped near the hair-cycle promoter; and ventral color and tail stripe mapped to a deletion (ΔSer) in exon 2, which is a conserved residue located in a protein domain that interacts with another pigment protein Attractin (21) (Fig. 2C, fig. S3, and table S5). These results suggest that multiple molecular mechanisms—including both protein-coding and cis-regulatory changes—are involved in color adaptation in these Sand Hills mice.

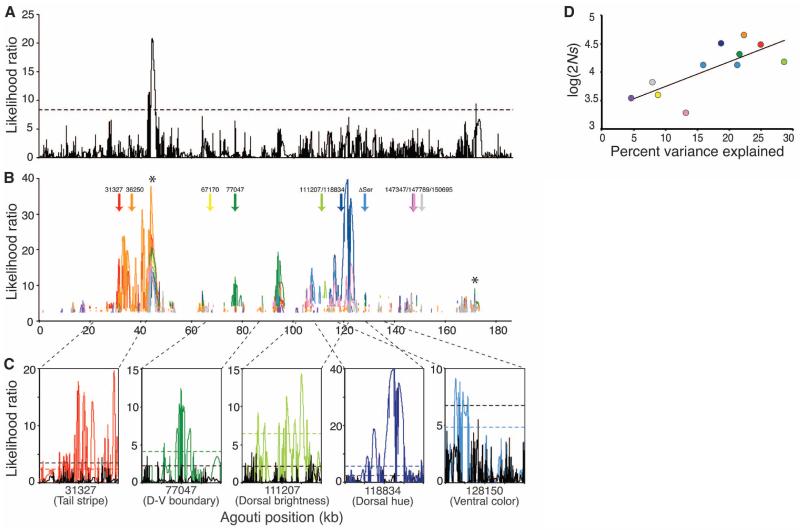

Having identified multiple regions contributing to coat-color lightness, we tested for positive selection on Agouti and these specific polymorphisms. We used dadi (22) to estimate a demographic model and parameters for our ecotonal population. We found evidence suggesting that the population experienced a recent (~2900 years ago) bottleneck, in which the population was reduced to 0.4% of its original size, followed by an exponential recovery to ~65% of its original size. Using this demographic model and the Sweepfinder framework (23), we evaluated patterns of selection in both the entire data set (i.e., all sampled individuals) and 10 polarized data sets (i.e., in which light and dark haplotypes are defined by the genotype at the candidate SNP of interest), following (11, 13, 24). We identified two regions with evidence of selection acting on all mice collected from this location, independent of coat color (Fig. 3A). By comparison, in polarized data sets, we found significant likelihood peaks clustered around the location of the polarizing SNPs (Fig. 3B and Table 1), consistent with recent selection acting on, or near, color-associated SNPs. Using one-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for our 10 candidate SNPs, we found that, compared with the dark-associated alleles (Fig. 3C and Table 1), light-associated alleles have a significantly better correspondence between the location of the polarizing SNP and the nearest significant likelihood-ratio (LR) peak (P = 0.037), a significantly greater number of sites surrounding the polarizing SNP that reject neutrality (P = 0.0063), and a significantly higher selection coefficient (P = 0.0063). Also, these differences are robust to choice of window size (tables S6 and S7). These observations are consistent with multiple targets of selection among the light, but not dark, alleles of Agouti.

Fig. 3.

Evidence of selection on light Agouti alleles. (A) Likelihood surface for all haplotypes with significance threshold [dotted line; determined by simulation (13)]. (B) Likelihood surface for only light haplotypes. Arrows indicate the positions of 10 candidate polymorphisms identified by association mapping (Fig. 2), and likelihood surfaces are colored according to the haplotypes determined by the corresponding polymorphism (e.g., the red LR trace was estimated using only those chromosomes carrying the light allele at position 31327). Significance thresholds were determined separately for each data set, and only LRs that are above these thresholds are shown. Asterisks give the location of peaks identified using all haplotypes (A). (C) Twenty-kbp windows (13) centered on the most strongly associated polymorphism for each trait (31327, tail stripe; 77047, dorsal-ventral boundary; 111207, dorsal brightness; 118834, dorsal hue; 128150 (ΔSer), tail stripe and ventral color). Likelihood surface for dark haplotypes only (solid black line) compared with those for light haplotypes only (solid colored lines). Dotted lines are significance thresholds (black, dark only; colored, light only). (D) Strength of selection (s) is significantly correlated with PVE (R2 = 0.56; Spearman’s rho = 0.76; P = 0.0071). Color of each SNP as in (B).

Table 1.

Selection on candidate regions identified using association mapping. PVE (R2) after controlling for population structure is given for each polymorphism. Asterisk denotes the ΔSer in exon 2 that was associated with more than one trait. These SNPs were then used to classify haplotypes as “light” or “dark” depending on observed phenotype-genotype correlations; selection analyses were performed separately on light and dark haplotypes. The distance (in base pairs) to the nearest site with a significant LR and the number of significant sites within a 20-kbp window surrounding the polarizing site are given for both light and dark alleles. Selection coefficients [s; assuming Ne = 53,080 mice (13)] and average 2Ns are also provided. Selection coefficients vary among traits; within each trait, SNPs with higher PVE have higher s.

| Candidate | Trait | PVE | Light allele |

Dark allele |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance | No. of sites |

2Ns | s | Distance | No. of sites |

2Ns | s | |||

| 118834 | Dorsal hue | 18.8 | 2393 | 2769 | 32,038 | 0.302 | 2607 | 207 | 2348 | 0.022 |

| 67170 | Dorsal brightness | 8.9 | 641 | 91 | 3926 | 0.037 | 2935 | 170 | 3977 | 0.038 |

| 111207 | Dorsal brightness | 28.7 | 881 | 588 | 15,296 | 0.144 | 1532 | 161 | 3047 | 0.029 |

| ΔASer* | Ventral color | 16 | 4084 | 802 | 13,366 | 0.126 | 41831 | 0 | 3121 | 0.029 |

| 36250 | d-v boundary | 22.4 | 7 | 5476 | 44,598 | 0.420 | 2880 | 1237 | 7122 | 0.067 |

| 77047 | d-v boundary | 21.7 | 0 | 1446 | 20,855 | 0.197 | 76 | 102 | 4959 | 0.047 |

| 147789 | d-v boundary | 13.3 | 2657 | 26 | 1921 | 0.018 | 741 | 369 | 2262 | 0.021 |

| 31327 | Tail stripe | 25 | 0 | 2986 | 30,324 | 0.286 | 3898 | 155 | 3992 | 0.038 |

| ΔSer* | Tail stripe | 21.3 | 4084 | 802 | 13,366 | 0.126 | 41,831 | 0 | 3121 | 0.029 |

| 147347 | Tail stripe | 4.7 | 733 | 1360 | 3447 | 0.033 | 24 | 176 | 1254 | 0.012 |

| 150695 | Tail stripe | 8 | 318 | 803 | 6730 | 0.063 | 1980 | 244 | 2399 | 0.023 |

We next estimated the strength of selection acting on these light-associated SNPs, using a maximum likelihood approach implemented in Sweepfinder (13, 23). Selection coefficients (s) ranged from 0.018 to 0.42 (Table 1), suggesting very strong selection in some cases. Selection strength varied as a function of both color trait and phenotypic effect size: We observed especially strong selection on SNPs associated with dorsal hue, dorsal-ventral boundary, and tail stripe (Table 1) and a positive correlation between the percent variation explained (PVE) and s across all light-associated SNPs (Spearman’s Rank correlation = 0.76, P = 0.0071, one-tailed) (Fig. 3D). Moreover, within each trait, we see a perfect rank correlation between PVE and s (e.g., for tail stripe associated SNPs Spearman’s rho = 1, P = 0, N = 4 SNPs). Thus, for each candidate SNP, the stronger its effect on color phenotype, the stronger the estimate of selection strength, suggesting that these mutations likely have minimal pleiotropic consequences. These results, when combined with results from the clay model experiment, the extensive recombination across this region, and the association mapping study, all support a scenario in which multiple independent Agouti mutations—each contributing to a distinct trait associated with the light phenotype—have been selected for cryptic coloration on the Sand Hills.

Although it has been suggested that pigmentation is an unusually simple trait (25), when deconstructed, we find both phenotypic and genetic complexity. The light pigmentation of the Sand Hills mice is composed of several genetically independent traits, and we find that mutations associated with each show clear signatures of selection. These results imply that each color trait, from dorsal color to tail stripe, independently affects fitness. We also demonstrate how a large-effect locus can fractionate into many small- to moderate-effect mutations. Moreover, although the gene Agouti has widespread effects on pigmentation, measurable pleiotropic effects are largely absent at the mutational level, serving as a reminder that, although it is commonplace to discuss the degree of pleiotropy of individual genes, it is individual mutations, not genes, that bring a population closer to its phenotypic optimum. Together, our results suggest that small, minimally pleiotropic mutations—even those occurring within a single gene—may provide a rapid route to adaptation along multiple phenotypic axes.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Duryea and G. Goncalves for laboratory assistance; J. Chupasko, E. Kay, E. Kingsley, M. Manceau, and J. Weber for field assistance; J. Demboski and the Denver Museum of Nature and Science for logistical support; and J. Chupasko for curation assistance. C.R.L. was supported by a Ruth Kirschstein National Research Service Award from NIH; B.K.P. by a Jane Coffins Child Postdoctoral Fellowship; J.D.J. and Y-P.P. by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the European Research Council, and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency; R.D.H.B. by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship and a Foundational Questions in Evolutionary Biology Postdoctoral Fellowship. Laboratory and fieldwork was funded by Putnam Expedition Grants from the MCZ Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), the Swiss National Science Foundation, Harvard University, and the National Science Foundation (DEB-0749958 to H.E.H.). P. maniculatus were collected under the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Scientific and Educational Permit 901, and voucher specimens were deposited in the MCZ’s Mammal Department. Sequence data were deposited in the NCBI Short Read Archive (accession no. SRP017939).

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/339/6125/1312/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S3

Tables S1 to S9

References (26–47)

References and Notes

- 1.Darwin C. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. John Murray; London: 1859. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher RA. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Oxford Univ. Press; Oxford: 1930. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nadeau NJ, Jiggins CD. Trends Genet. 2010;26:484. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stapley J, et al. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010;25:705. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoekstra HE, Hirschmann RJ, Bundey RA, Insel PA, Crossland JP. Science. 2006;313:101. doi: 10.1126/science.1126121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rebeiz M, Pool JE, Kassner VA, Aquadro CF, Carroll SB. Science. 2009;326:1663. doi: 10.1126/science.1178357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankel N, et al. Nature. 2011;474:598. doi: 10.1038/nature10200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prasad KVSK, et al. Science. 2012;337:1081. doi: 10.1126/science.1221636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loope DB, Swinehart J. Great Plains Res. 2000;10:5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dice LR. Contrib. Lab. Vertebr. Genet. Univ. Mich. 1941;15:1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linnen CR, Kingsley EP, Jensen JD, Hoekstra HE. Science. 2009;325:1095. doi: 10.1126/science.1175826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vignieri SN, Larson JG, Hoekstra HE. Evolution. 2010;64:2153. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Materials and methods are available as supplementary materials on Science online.

- 14.Dice LR. Contrib. Lab. Vertebr. Biol. Univ. Mich. 1947;34:1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Domingues VS, et al. Evolution. 2012;66:3209. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kingsley EP, Manceau M, Wiley CD, Hoekstra HE. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laurie CC, et al. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guan Y, Stephens M. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2011;5:1780. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bultman SJ, et al. Genes Dev. 1994;8:481. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.4.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vrieling H, Duhl DMJ, Millar SE, Miller KA, Barsh GS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:5667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson PJ, et al. Chem. Biol. 2006;13:1297. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutenkunst RN, Hernandez RD, Williamson SH, Bustamante CD. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen R, et al. Genome Res. 2005;15:1566. doi: 10.1101/gr.4252305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meiklejohn CD, Kim Y, Hartl DL, Parsch J. Genetics. 2004;168:265. doi: 10.1534/genetics.103.025494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rockman MV. Evolution. 2012;66:1. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]