Abstract

Modern advances in cancer immunotherapy have led to the development of active immunotherapy that utilizes tumor-associated antigens to induce a specific immune response against the tumor. Current methods of immunotherapy implementation are based on the principle that tumor-associated antigens are capable of being processed by antigen-presenting cells and inducing an activated cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-specific immune response that targets the tumor cells. Antigen internalization and processing by antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells, or macrophages results in their surface association with MHC class I molecules, which can be recognized by an antigen-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte adaptive immune response. With the aim of augmenting current immunotherapeutic modalities, much effort has been directed towards enhancing antigen-presenting cell activation and optimizing the processing of tumor-associated antigens and major histocompatibility molecules. The goal of these immunotherapy modifications is to ultimately improve the adaptive specific immune response in killing of tumor cells while sparing normal tissues. Immunotherapy has been actively studied and applied in glioblastomas. Preclinical animal models have shown the feasibility of an active immunotherapy approach through the utilization of tumor vaccines, and recently several clinical studies have also been initiated. Recently, endogenous heat-shock proteins have been implicated in the mediation of both the adaptive and innate immune responses. They are now being investigated as a potential modality and adjuvant to immunotherapy, and they represent a promising novel treatment for human glioblastomas.

Keywords: active immune response, antigen, antigen-presenting cells, cancer vaccines, CTL, heat-shock proteins, immunotherapy, T-cell lymphocytes

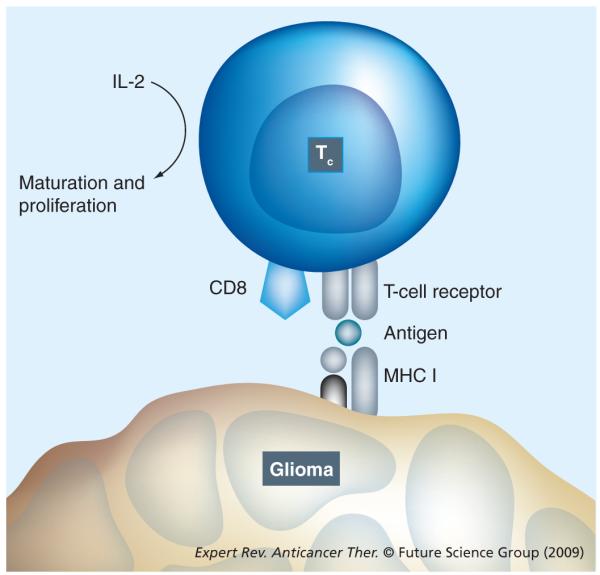

Active immunotherapy utilizing tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) to induce a specific host immune response against tumor cells has been an active area of advancement in cancer immunotherapy. TAAs are capable of being processed by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and inducing an activated cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL)-specific immune response against the tumor cells. Antigen internalization and processing by APCs, such as dendritic cells or macrophages, results in their surface association with MHC class I molecules [1]. These antigen complexes can be recognized by antigen-specific CTLs, resulting in a robust specific immune response (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Cytotoxic T cell showing the MHC class I molecule-mediated antigen-dependent T-cell mechanism for cell killing and antigen recognition.

With the aim of augmenting current immunotherapeutic modalities, much effort has been focused on optimizing the process of APC activation using TAAs and MHC molecules [1]. The goal of these immunotherapy modifications is ultimately to improve the specific immune response in killing of tumor cells while sparing normal tissues.

The most common form of glioma in humans, glioblastoma multiforme(GBM) carries a dismal prognosis despite traditional adjuvant therapies, such as radiation and chemotherapy. Recent immunotherapeutic modalities for GBM have included tumor vaccines utilizing purified tumor peptides and tumor-specific antigens to whole tumor lysates or cells with the aim of generating an adaptive, specific anti-tumor immune response. A great challenge in glioma immunotherapy has been the neoplasm’s inherent immune suppression and adept methods of immune escape. Inducing an immune response from the patient through active immunotherapy may help address the challenges and obstacles of this immune suppression and evasion exhibited by glioblastoma tumors. Preclinical animal models have shown the feasibility of an active immunotherapy approach through the utilization of tumor vaccines and recently several clinical studies have also been initiated. Recently, endogenous heat-shock proteins (HSPs) have been implicated in the mediation of both the adaptive and innate immune responses, and their therapeutic role is now being investigated. They represent a promising novel immunotherapeutic modality for human glioblastomas.

Characteristics & properties of HSPs

In flies, increased environmental temperature was associated with an increase in transient expression of specific proteins with molecular weights between 26 and 70 kDa [2]. These proteins were coined as HSPs for their response to ambient environmental temperature. Subsequently, further investigations have demonstrated that these HSPs are also induced by environmental and pathologic insults that alter protein folding, such as hyperthermia, anoxia, glucose deprivation, oxidative damage, irradiation, infection and inflammation [3]. HSPs are highly conserved among all organisms and these abundant proteins are best known for their activity as molecular protein chaperones. These HSP chaperones are critical players in the folding, assembly and transport of nascent peptides, as well as in the degradation of misfolded proteins. An environment of ‘stress’ or distressed conditions results in misfolded protein abnormalities, which subsequently lead to an increase in HSP elements, in part from activation of HSP transcription factors within the cell. Under normal conditions, HSPs account for approximately 10% of proteins in the cell [4], but demonstrate as much as a threefold increase in expression levels in response to stressful cellular conditions to mitigate abnormal protein folding and dysfunction [4–6].

There are five major families of HSPs, each initially classified by their approximate molecular sizes: HSP 60, HSP 70, HSP 90, HSP 100 and the small HSPs [7]. Although the initial classification of HSPs was based on apparent molecular weights, more recently HSPs have been grouped into families based on their amino acid sequence and their phylogenetic relationships. These HSPs are commonly constitutively expressed but can also be induced to increase expression. In addition to these main HSPs, which are found in the nucleus and cytoplasm, another HSP family of stress proteins, such as glucose-regulated proteins (Grps), are found in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [8]. This other HSP-related family of stress proteins (Grp 78/BiP, Grp 94 and Grp 170) is induced by similar conditions to those that alter protein function but instead alter ER function, such as hypoglycemia, hypoxia and exposure to heavy metals, as well as glycosylation and disturbances in calcium homeostasis [9,10]. While intracellular HSPs function to protect cells from protein misfolding, protein dysfunction and cell-signaled apoptosis, extracellular or membrane-bound HSPs play an important role in modulating immune-associated interactions of the cell [7].

Role of HSPs in an immune response

Although not all HSPs stimulate an antigen-specific CTL response, several stress HSP family proteins, such as Grp 96, HSP 90, HSP 70, HSP 110 and HSP 170, have been demonstrated to be among the most immunogenic stress proteins [11,12].

The recognition that exposing host mice to total soluble proteins of tumor lysates and irradiated tumor cells could elicit an immune protective response provided the impetus for investigations into a tumor-specific immune response. Furthermore, these challenged mice only exhibited immunity against the specific cancers when rechallenged, but not against other types of cancer, which suggested the mechanism and character of a unique and individual-tumor specificity of immunity mediated by unique TAAs [13–15].

Attempting to isolate and characterize the immunogenic component of these tumors, cancer-cell homogenates were fractionated by chromatography and again challenged in host animals to determine the potential efficacy of tumor immunogenesis [16]. Subsequently, molecules capable of stimulating an anti-tumor immune response in the host animals were then repeatedly purified by recurring fractionations until homogeneous, which further identified these anti-tumor immune-stimulating proteins as belonging to the HSP family, such as Grp 96, followed by HSP 70 and HSP 90, then HSP 110 and HSP 170 [11,15–17]. Although HSPs derived from cancers were found to stimulate an immunogenic response, HSPs isolated from adjacent normal tissues or from other cancer tissues did not elicit an immune anti-tumor response [15]. This suggested that the tumor antigen associated with the HSP was able to induce the appropriate anti-tumor immune response. The tumor specificity of the cancer-derived HSP-associated immune response was not revealed by differences in DNA sequencing, structural variations or somatic polymorphisms from their nontumor HSP counterparts, which further suggested an antigenic binding mechanism of HSP to tumor antigens [8]. This was confirmed by investigations that demonstrated the loss of immunogenesis for tumor-derived HSPs in peptide-deprived conditions [15]. Furthermore, replenishment of tumor peptides to the HSPs reconstituted an effective anti-tumor immune protection in host animals again [18]. Taken together, this evidence demonstrates that the tumor antigenic protein associated with the HSP is critical to induction of an active specific anti-tumor immune response. Conversely, with equal importance, these same tumor-inducing antigens when associated with other proteins, such as albumin, failed to induce an active CTL immune response against the tumor antigens and against the tumor itself [18]. This also suggests a unique role of immunogenicity conferred onto these TAAs by being carried and associated with HSPs that is absent when these same proteins are carried by other non-HSPs. Lastly, this evidence demonstrates that neither HSPs nor their TAAs were immunogenic when taken individually, but the combination of these tumor antigens when chaperoned by HSPs could effectively induce a specific CTL anti-tumor immune response in preclinical animal models [11,18–20].

It is unclear whether the ability to bind peptides and elicit an immune response can be attributed to its chaperoning and protein-folding activities; however, investigations into the structure of HSPs have provided some insights into the differential peptide-binding characteristics of HSPs [21–23]. Despite the difficulty of eluting peptides from their chaperone proteins, structural analysis studies have allowed some characterization of the protein-binding properties of HSPs. HSP 70 is one of the most studied HSP chaperone proteins, with its antigen-binding properties derived from the peptide-binding domain at the N-terminus [21]. Peptide-binding domains of the high-molecular-weight HSPs, such as HSP 70, depend on ATP. This energy-consuming process of antigen binding favors peptide association when bound to ADP and peptide disassociation when bound to ATP [21]. With their negatively charged binding domains, HSPs have a protein binding preference for small, hydrophobic peptides that are 8–26 amino acids in length [24–26]. Studies of HSP 90 have also revealed both an N-terminal peptide-binding domain and a C-terminal binding domain [27–29]. The investigations on HSP 90 have demonstrated that the peptides associated with the N-terminal binding site were unfolded proteins that were longer than ten amino acids, while the C-terminal binding domain preferred binding amino acid peptides that were partially folded [25,28,30]. A more complete understanding of binding-domain characteristics for specific HSPs may allow for improved selection or synthesis of peptides in development of potential antigen-directed chaperone vaccinations with enhanced specific targeting of tumors

HSP interactions with APCs

The ability of HSPs to bind, fold and chaperone antigenic tumor peptides allows it to induce a specific immunity against the cancer cells – the origin of the antigen peptides. Specific mechanisms by which HSP–peptide complexes induce an anti-tumor immune response are being investigated through the HSP–peptide interaction with an APC.

Investigations with tumor-derived HSPs in an environment with depletion of macrophages and APCs in the host animals confirmed that the ability of the HSP–peptide complex to induce an active, specific immune response was dependent on the presence of APCs and phagocytic mechanisms [15,31]. It has been suggested that macrophages play a critical role in the transfer of antigenic material from the chaperone HSPs to the APCs for MHC presentation instead of a direct peptide transfer from HSP to APCs [13].

The high efficiency of APCs to present the antigen from the HSP–peptide complex led to further studies for a potential HSP-specific receptor on macrophages and APCs that could suggest a mechanism for this reliable uptake of peptide from these small quantities of HSP–peptide complexes [32]. This efficient uptake of HSP-associated antigen was demonstrated with the finding that HSP-chaperoned peptides are significantly more efficient at being loaded and presenting their antigens onto MHC molecules than free peptides [13,20,33]. Some evidence suggests that HSP–peptide complexes undergo internalization by macrophages through a clathrin-coated receptor-mediated endocytotic mechanism, and several potential HSP-specific receptors have also been identified on the surface of APCs [34]. The most studied HSP-specific receptor is the CD91 (α-2-macroglobulin) receptor, found on macrophages and DCs. This CD91 receptor plays a critical role in the internalization of Grp 96, HSP 70, HSP 90 and calreticulin [35–39]. LOX-1, a member of the scavenger receptor family, is another HSP-associated receptor that has been shown to play a role in HSP 70 uptake and internalization [39,40].

Upon binding of HSP–peptide complexes to these HSP-specific receptors for internalization, potential antigenic peptides are intracellularly processed by the proteosome and degraded by peptidases. Subsequently, this allows for some peptide fragments to be transported by the ATP-dependent transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) to the ER for extracellular presentation [13,31,40–42]. Alternatively, the antigenic protein peptide can also be processed by a TAP-independent pathway through an endosome for presentation of potential antigenic proteins on MHC molecules [40–42].

HSP induction of proinflammatory cytokine activity

Another consequence of the interaction between HSPs and APCs is the natural stimulation of inflammatory cytokine release by macrophages and dendritic cells [9,11,43,44]. The presence of HSPs alone, irrespective of bound peptides, can stimulate the release of potent proinflammatory cytokines that are known to be important in antigen-specific adaptive immunity, which serves as a convenient adjuvant for enhancing protective anti-tumor active immunity [9,11,44].

Expert commentary

Heat-shock proteins represent a promising potential immunotherapeutic modality for cancer treatment. The malignant cell division, necrosis and metabolic alterations by malignant cancers, such as GBM, are natural inducers of HSP expression. It is highly likely that these cancers utilize the homeostatic and peptide protective nature of these HSPs for their own proliferative tumor growth. HSP overexpression has been associated with poorer prognosis in several cancers [45–47]. HSP proteins may also play a role in the anti-apoptosis mechanisms of cancer cells. Novel therapeutic immunotherapies aim to utilize HSPs as an ex vivo-generated cancer vaccine to stimulate an active, anti-tumor immune response against cancer. One of the significant advantages of a HSP-derived vaccine is that a preidentified tumor-specific antigen is not required. A tumor-specific antigen has not yet been fully established against cancers such as GBM and, hence, an advantage of HSP modalities is that this immunotherapy can be performed without the explicit identification of immunogenic antigens or epitopes. This multiple antigen approach to cancers such as glioblastoma allows a broader repertoire of antigens to be utilized as potential antigenic proteins. Furthermore, this broader coverage of HSP vaccines would allow individualized antigenic profile immune responses against each individual cancer antigen ‘fingerprint’. Currently, HSP-based vaccines are being investigated against various cancers, including ongoing clinical trials against human GBM.

Five-year view

Heat-shock protein-based vaccines against difficult cancers, such as GBMs, continue to be advanced and investigated in clinical trials. Successful clinical trials may help immunotherapy based on HSP vaccines to be utilized as an anti-tumor modality with decreased morbidity compared with radiochemotherapy. This may also enhance the quality of life in these cancer patients. Also, these potential HSP glioma vaccines represent a more individualized approach to cancer treatment as HSPs exhibit the ability to bind multiple immunogenic peptides specific to the individual’s tumor. They may potentially stimulate a more precise anti-tumor immune response against the individual’s tumor and the tumors’ unique ‘fingerprint’. Over the next 5 years, HSP vaccine trials with various purified protein peptides, various antigens and whole cell lysates will determine the feasibility of utilizing HSP vaccines against malignant cancers, such as GBMs. Our own clinical trials of an autologous high-molecular-weight HSP vaccine for malignant gliomas is in progress and has shown promising preliminary results. As these immunotherapeutic modalities are improved and advanced, novel methods to overcome and bypass the inherent immune suppression of GBMs will have to be developed in order to enhance the efficacy of immunotherapeutic approaches to malignant tumors.

Key issues.

Immunotherapy approaches can be based on the principle that tumor-associated antigens are capable of being processed by antigen presenting cells (APCs) and inducing an activated cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL)-specific immune response that targets the tumor cells.

Recently, endogenous heat-shock proteins (HSPs) have been implicated in the mediation of both the adaptive and innate immune responses. They are now being investigated as a potential modality and adjuvant to immunotherapy, and they represent a promising novel treatment for human glioblastomas.

HSPs are highly conserved among all organisms and these abundant proteins are best known for their activity as molecular protein chaperones. These HSP chaperones are critical players in the folding, assembly and transport of nascent peptides, as well as in the degradation of misfolded proteins.

There are five major families of HSPs, each classified by their approximate molecular sizes: HSP 60, HSP 70, HSP 90, HSP 100 and the small HSPs.

A more complete understanding of binding-domain characteristics for specific HSPs may allow for improved selection or synthesis of peptides in development of potential antigen-directed chaperone vaccinations with enhanced specific targeting of tumors.

Investigations with tumor-derived HSPs in an environment with depletion of macrophages and APCs in the host animals confirmed that the ability of the HSP–peptide complex to induce an active, specific immune response was dependent on the presence of APCs and phagocytic mechanisms. It has been suggested that macrophages play a critical role in the transfer of antigenic material from the chaperone HSPs to the APC for MHC presentation instead of a direct peptide transfer from HSP to APCs.

The presence of HSPs alone, irrespective of bound peptides, can stimulate the release of potent proinflammatory cytokines that are known to be important in antigen-specific adaptive immunity, which serve as a convenient adjuvant for enhancing protective anti-tumor, active immunity.

Currently, HSP-based vaccines are being investigated against various cancers, including human glioblastoma multiforme.

These potential HSP glioma vaccines represent a more individualized approach to cancer treatment since HSPs exhibit the ability to bind multiple immunogenic peptides unique to the individual’s tumor, and may potentially stimulate a more precise anti-tumor immune response.

As these immunotherapeutic modalities are improved and advanced, novel methods to overcome and bypass the inherent immune suppression of glioblastoma multiformes will have to be developed in order to enhance the efficacy of immunotherapeutic approaches to malignant tumors.

Acknowledgments

Isaac Yang was partially supported by a UCSF Clinical and Translational Scientist Training Research Award and a NIH National Research Service Award grant. Seunggu Han was funded by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Research Training Fellowship. Andrew T Parsa was partially funded by a Reza and Georgianna Khatib Endowed Chair in Skull Base Tumor Surgery.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Isaac Yang, Department of Neurological Surgery, University of California at San Francisco, 505 Parnassus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94143, USA Tel.: +1 415 353 3904 Fax: +1 415 353 3907 yangi@neurosurg.ucsf.edu.

Seunggu Han, Department of Neurological Surgery, University of California at San Francisco, 505 Parnassus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94143, USA Tel.: +1 415 353 2629 Fax: +1 415 353 3907 seunggu.han@ucsf.edu.

Andrew T Parsa, Department of Neurological Surgery, University of California at San Francisco, 505 Parnassus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94143, USA Tel.: +1 415 353 2629 Fax: +1 415 353 3907 parsaa@neurosurg.ucsf.edu.

References

- 1.Yang I, Kremen TJ, Giovannone AJ, et al. Modulation of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules and major histocompatibility complex-bound immunogenic peptides induced by interferon-α and interferon-γ treatment of human glioblastoma multiforme. J. Neurosurg. 2004;100(2):310–319. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.2.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park HG, Han SI, Oh SY, Kang HS. Cellular responses to mild heat stress. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62(1):10–23. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young JC, Agashe VR, Siegers K, Hartl FU. Pathways of chaperone-mediated protein folding in the cytosol. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5(10):781–791. doi: 10.1038/nrm1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soo ET, Yip GW, Lwin ZM, Kumar SD, Bay BH. Heat shock proteins as novel therapeutic targets in cancer. In Vivo. 2008;22(3):311–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pockley AG. Heat shock proteins as regulators of the immune response. Lancet. 2003;362(9382):469–476. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voellmy R. Feedback regulation of the heat shock response. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2006;(172):43–68. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29717-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmitt E, Gehrmann M, Brunet M, Multhoff G, Garrido C. Intracellular and extracellular functions of heat shock proteins: repercussions in cancer therapy. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007;81(1):15–27. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srivastava PK. Peptide-binding heat shock proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum: role in immune response to cancer and in antigen presentation. Adv. Cancer Res. 1993;62:153–177. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manjili MH, Wang XY, Park J, Facciponte JG, Repasky EA, Subjeck JR. Immunotherapy of cancer using heat shock proteins. Front. Biosci. 2002;7:d43–d52. doi: 10.2741/manjili. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subjeck JR, Shyy TT. Stress protein systems of mammalian cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1986;250(1 Pt 1):C1–17. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1986.250.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Binder RJ. Heat shock protein vaccines: from bench to bedside. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2006;25(5–6):353–375. doi: 10.1080/08830180600992480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srivastava PK, Amato RJ. Heat shock proteins: the ‘swiss army knife’ vaccines against cancers and infectious agents. Vaccine. 2001;19(17–19):2590–2597. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suto R, Srivastava PK. A mechanism for the specific immunogenicity of heat shock protein-chaperoned peptides. Science. 1995;269(5230):1585–1588. doi: 10.1126/science.7545313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamura Y, Peng P, Liu K, Daou M, Srivastava PK. Immunotherapy of tumors with autologous tumor-derived heat shock protein preparations. Science. 1997;278(5335):117–120. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Udono H, Srivastava PK. Comparison of tumor-specific immunogenicities of stress-induced proteins Gp96, HSP90, and HSP70. J. Immunol. 1994;152(11):5398–5403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srivastava PK, Deleo AB, Old LJ. Tumor rejection antigens of chemically induced sarcomas of inbred mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83(10):3407–3411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srivastava PK, Menoret A, Basu S, Binder RJ, Mcquade KL. Heat shock proteins come of age: primitive functions acquire new roles in an adaptive world. Immunity. 1998;8(6):657–665. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80570-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blachere NE, Li Z, Chandawarkar RY, et al. Heat shock protein-peptide complexes, reconstituted in vitro, elicit peptide-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response and tumor immunity. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186(8):1315–1322. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Przepiorka D, Srivastava PK. Heat shock protein–peptide complexes as immunotherapy for human cancer. Mol. Med. Today. 1998;4(11):478–484. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(98)01345-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Binder RJ, Blachere NE, Srivastava PK. Heat shock protein-chaperoned peptides but not free peptides introduced into the cytosol are presented efficiently by major histocompatibility complex I molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(20):17163–17171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castelli C, Rivoltini L, Rini F, et al. Heat shock proteins: biological functions and clinical application as personalized vaccines for human cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2004;53(3):227–233. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0481-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicchitta CV, Carrick DM, Baker-Lepain JC. The messenger and the message: Gp96 (grp94)-peptide interactions in cellular immunity. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2004;9(4):325–331. doi: 10.1379/CSC-62.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang XY, Li Y, Yang G, Subjeck JR. Current ideas about applications of heat shock proteins in vaccine design and immunotherapy. Int. J. Hyperthermia. 2005;21(8):717–722. doi: 10.1080/02656730500226407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grossmann ME, Madden BJ, Gao F, et al. Proteomics shows HSP70 does not bind peptide sequences indiscriminately in vivo. Exp. Cell Res. 2004;297(1):108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh-Jasuja H, Hilf N, Arnold-Schild D, Schild H. The role of heat shock proteins and their receptors in the activation of the immune system. Biol. Chem. 2001;382(4):629–636. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu X, Zhao X, Burkholder WF, et al. Structural analysis of substrate binding by the molecular chaperone dnak. Science. 1996;272(5268):1606–1614. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graner MW, Bigner DD. Chaperone proteins and brain tumors: potential targets and possible therapeutics. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7(3):260–278. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704001188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheibel T, Weikl T, Buchner J. Two chaperone sites in HSP90 differing in substrate specificity and ATP dependence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95(4):1495–1499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Workman P. Altered states: selectively drugging the HSP90 cancer chaperone. Trends Mol. Med. 2004;10(2):47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Obermann WM, Sondermann H, Russo AA, Pavletich NP, Hartl FU. In vivo function of HSP90 is dependent on ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143(4):901–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang XY, Kaneko Y, Repasky E, Subjeck JR. Heat shock proteins and cancer immunotherapy. Immunol. Invest. 2000;29(2):131–137. doi: 10.3109/08820130009062296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srivastava PK, Udono H, Blachere NE, Li Z. Heat shock proteins transfer peptides during antigen processing and ctl priming. Immunogenetics. 1994;39(2):93–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00188611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roigas J, Wallen ES, Loening SA, Moseley PL. Heat shock protein (HSP72) surface expression enhances the lysis of a human renal cell carcinoma by IL-2 stimulated NK cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1998;451:225–229. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5357-1_35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnold-Schild D, Hanau D, Spehner D, et al. Cutting edge: receptor-mediated endocytosis of heat shock proteins by professional antigen-presenting cells. J. Immunol. 1999;162(7):3757–3760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basu S, Binder RJ, Ramalingam T, Srivastava PK. Cd91 is a common receptor for heat shock proteins Gp96, HSP90, HSP70, and calreticulin. Immunity. 2001;14(3):303–313. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Binder RJ, Han DK, Srivastava PK. Cd91: a receptor for heat shock protein Gp96. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1(2):151–155. doi: 10.1038/77835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Binder RJ, Karimeddini D, Srivastava PK. Adjuvanticity of α 2-macroglobulin, an independent ligand for the heat shock protein receptor Cd91. J. Immunol. 2001;166(8):4968–4972. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.4968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Binder RJ, Srivastava PK. Essential role of Cd91 in re-presentation of Gp96-chaperoned peptides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(16):6128–6133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308180101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delneste Y, Magistrelli G, Gauchat J, et al. Involvement of Lox-1 in dendritic cell-mediated antigen cross-presentation. Immunity. 2002;17(3):353–362. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishikawa M, Takemoto S, Takakura Y. Heat shock protein derivatives for delivery of antigens to antigen presenting cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2008;354(1–2):23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castellino F, Boucher PE, Eichelberg K, et al. Receptor-mediated uptake of antigen/heat shock protein complexes results in major histocompatibility complex class I antigen presentation via two distinct processing pathways. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191(11):1957–1964. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.11.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takakura Y, Takemoto S, Nishikawa M. HSP-based tumor vaccines: state-of-the-art and future directions. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2007;9(4):385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Basu S, Binder RJ, Suto R, Anderson KM, Srivastava PK. Necrotic but not apoptotic cell death releases heat shock proteins, which deliver a partial maturation signal to dendritic cells and activate the NF-κB pathway. Int. Immunol. 2000;12(11):1539–1546. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.11.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang HH, Mao CY, Teng LS, Cao J. Recent advances in heat shock protein-based cancer vaccines. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2006;5(1):22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calderwood SK, Khaleque MA, Sawyer DB, Ciocca DR. Heat shock proteins in cancer: chaperones of tumorigenesis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31(3):164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calderwood SK, Theriault JR, Gong J. Message in a bottle: role of the 70 kDa heat shock protein family in antitumor immunity. Eur J. Immunol. 2005;35(9):2518–2527. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ciocca DR, Calderwood SK. Heat shock proteins in cancer: diagnostic, prognostic, predictive, and treatment implications. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2005;10(2):86–103. doi: 10.1379/CSC-99r.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]