Abstract

Study Objectives:

Adolescents with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) represent an important but understudied subgroup of long-term continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) users. The purpose of this qualitative study was to identify factors related to adherence from the perspective of adolescents and their caregivers.

Methods:

Individual open-ended, semi-structured interviews were conducted with adolescents (n = 21) and caregivers (n = 20). Objective adherence data from the adolescents' CPAP machines during the previous month was obtained. Adolescents with different adherence levels and their caregivers were asked their views on CPAP. Using a modified grounded theory approach, we identified themes and developed theories that explained the adolescents' adherence patterns.

Results:

Adolescent participants (n = 21) were aged 12-18 years, predominantly male (n = 15), African American (n = 16), users of CPAP for at least one month. Caregivers were mainly mothers (n = 17). Seven adolescents had high use (mean use 381 ± 80 min per night), 7 had low use (mean use 30 ± 24 min per night), and 7 had no use during the month prior to being interviewed. Degree of structure in the home, social reactions, mode of communication among family members, and perception of benefits were issues that played a role in CPAP adherence.

Conclusions:

Understanding the adolescent and family experience of using CPAP may be key to increasing adolescent CPAP adherence. As a result of our findings, we speculate that health education, peer support groups, and developmentally appropriate individualized support strategies may be important in promoting adherence. Future studies should examine these theories of CPAP adherence.

Citation:

Prashad PS; Marcus CL; Maggs J; Stettler N; Cornaglia MA; Costa P; Puzino K; Xanthopoulos M; Bradford R; Barg FK. Investigating reasons for CPAP adherence in adolescents: a qualitative approach. J Clin Sleep Med 2013;9(12):1303-1313.

Keywords: Qualitative, interviews, adolescent, CPAP adherence

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) affects approximately 2% of children and adolescents.1 OSAS in children may result in severe complications if left untreated, such as growth failure, pulmonary hypertension, neurocognitive deficits, behavioral problems, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.2–6

In young children, OSAS can often be treated with adenotonsillectomy. However, in adolescents, adenotonsillectomy may not be effective, as adenoids and tonsils involute with age7,8 and obesity is more likely to be present. While weight loss may be an effective treatment for OSAS in this age group, it is difficult to achieve and maintain, particularly for those with severe obesity. Therefore, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) has become the mainstay of treatment of OSAS in adolescents.

CPAP is an effective treatment for OSAS in adolescents, but adherence remains a challenge.9–12 CPAP adherence patterns of adolescents have not been extensively studied, but studies of medication adherence in other adolescent groups, such as asthmatics, epileptics, and diabetics have demonstrated poor adherence.13,14 Poor adherence in adolescents may be related to not understanding or not perceiving the benefits of the treatment, wanting to conform to peers, and rebelling against authority.15 In addition, adolescents may have little parental supervision of CPAP use. Because of a lack of published literature, we performed an exploratory study from the perspective of adolescents and their caregivers. To our knowledge, this is the first study focused on the adolescent age group.

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is an effective treatment for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) in adolescents, when used, but adherence is a challenge. The purpose of the current study was to identify and explore factors that influenced adolescent CPAP use.

Study Impact: This is one of the first studies to provide information about reasons for continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) adherence and nonadherence in adolescents, a growing group of CPAP users who have been understudied.

The purpose of the study was to identify and explore factors that influenced adolescent CPAP use, using a modified grounded theory approach.16 Grounded theory is a qualitative method that seeks to generate theories from the data, to offer explanations for the phenomenon being explored.

METHODS

This exploratory study consisted of qualitative semi-structured interviews and a download of the adolescent's adherence data from his or her CPAP machine during the previous month. As experienced physicians in pediatric sleep medicine, it was impossible to set aside our preconceived notions regarding CPAP adherence. As a consequence, we acknowledged these notions and used them to generate a tentative framework from which we developed the initial interview questions. This framework led us to explore issues of stress, parenting style, family structure and organization, behavior and emotional problems, knowledge about OSAS, and the purpose and benefits of treatment with CPAP. We used these notions to identify and explore factors that may act as barriers and facilitators of CPAP use.

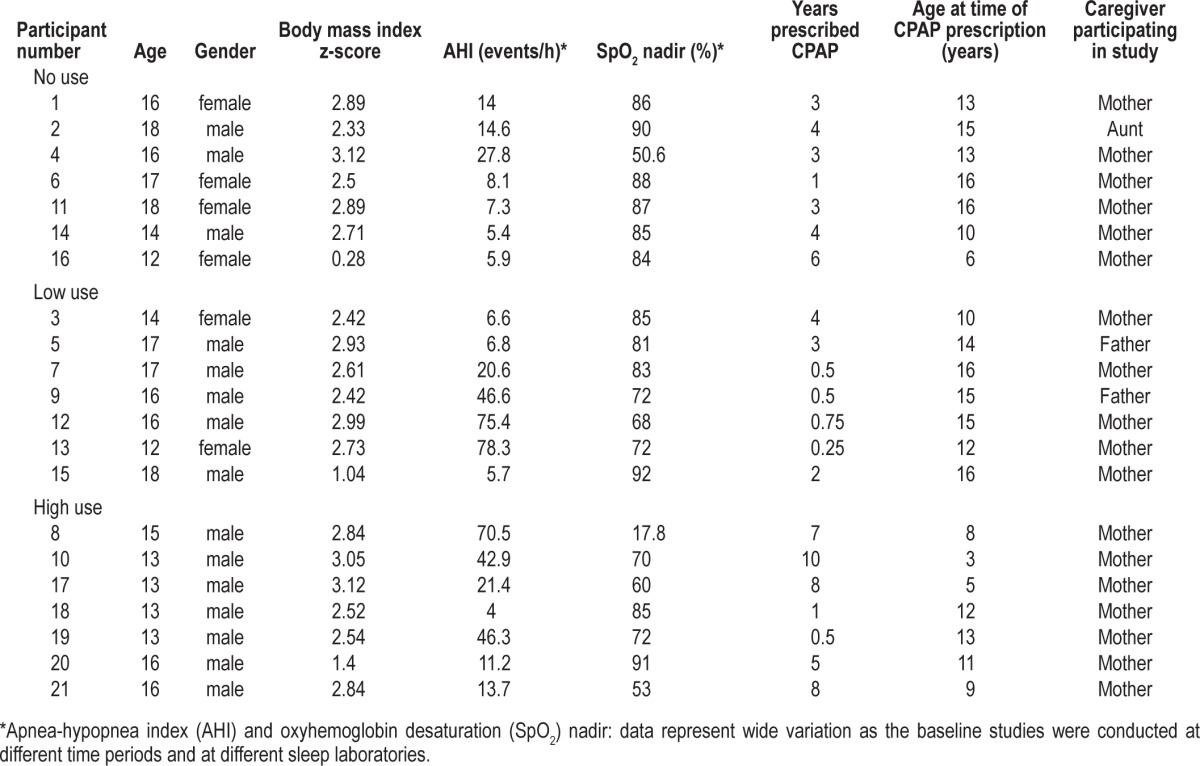

Details of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Each participant had been diagnosed with OSAS by polysomnography. All participants had been prescribed CPAP therapy as part of their usual care for at least one month prior to recruitment. Details of how long the study participants had been prescribed CPAP are shown in Table 1. Participants were purposively recruited across the spectrum of adherence. We also included a caregiver for each adolescent in the study, defined as a parent, relative, or other adult with the responsibility of caring for the adolescent. Exclusion criteria included non-English speakers, developmental delays, and the presence of another severe chronic medical condition.

Table 1.

Details of the study participants

Approval was obtained from the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board. Parental/guardian informed consent was obtained, as well as child assent for those younger than 18 years of age. Participants were provided reimbursement for their time.

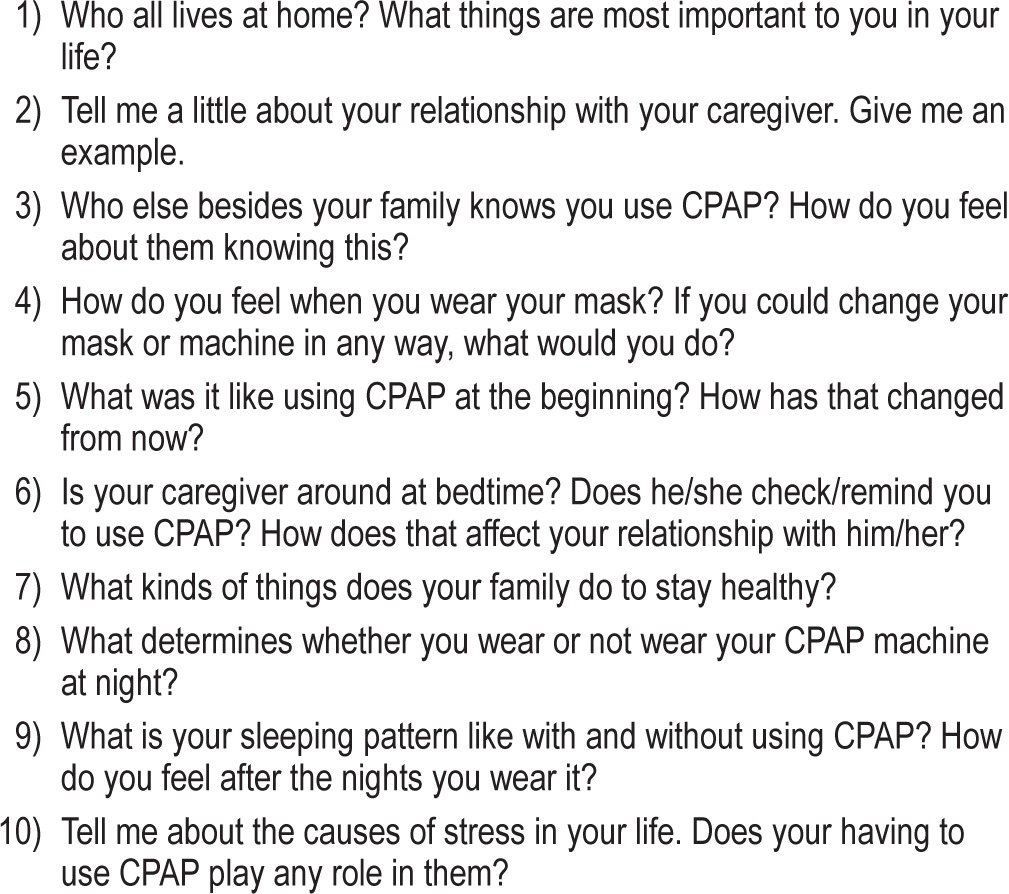

Each individual semi-structured interview was conducted by one of three interviewers conversant with qualitative methodology and interviewing techniques. The approach used was to ask questions exploring the issues within the framework developed for the study. The semi-structured nature of the interview was piloted with a related caregiver and adolescent. Their feedback helped us identify appropriate language and phrases that would be understood by the participants. Examples of the type of questions used to explore these issues are shown in Table 2. By using a semi-structured approach, we ensured that the same topics were explored with each family; however, the interviewers had the scope to be responsive to the issues that arose during the interview and to ask more probing questions. Most interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and reviewed by the interviewer for accuracy. Three interviewees refused to have their interviews audio recorded, so notes were taken instead. In addition, the interviewers took field notes and noted general impressions for each interview, which were used in the analysis process. The mean time for interviews was 30 minutes.

Table 2.

Examples of semi-structured interview questions for adolescents

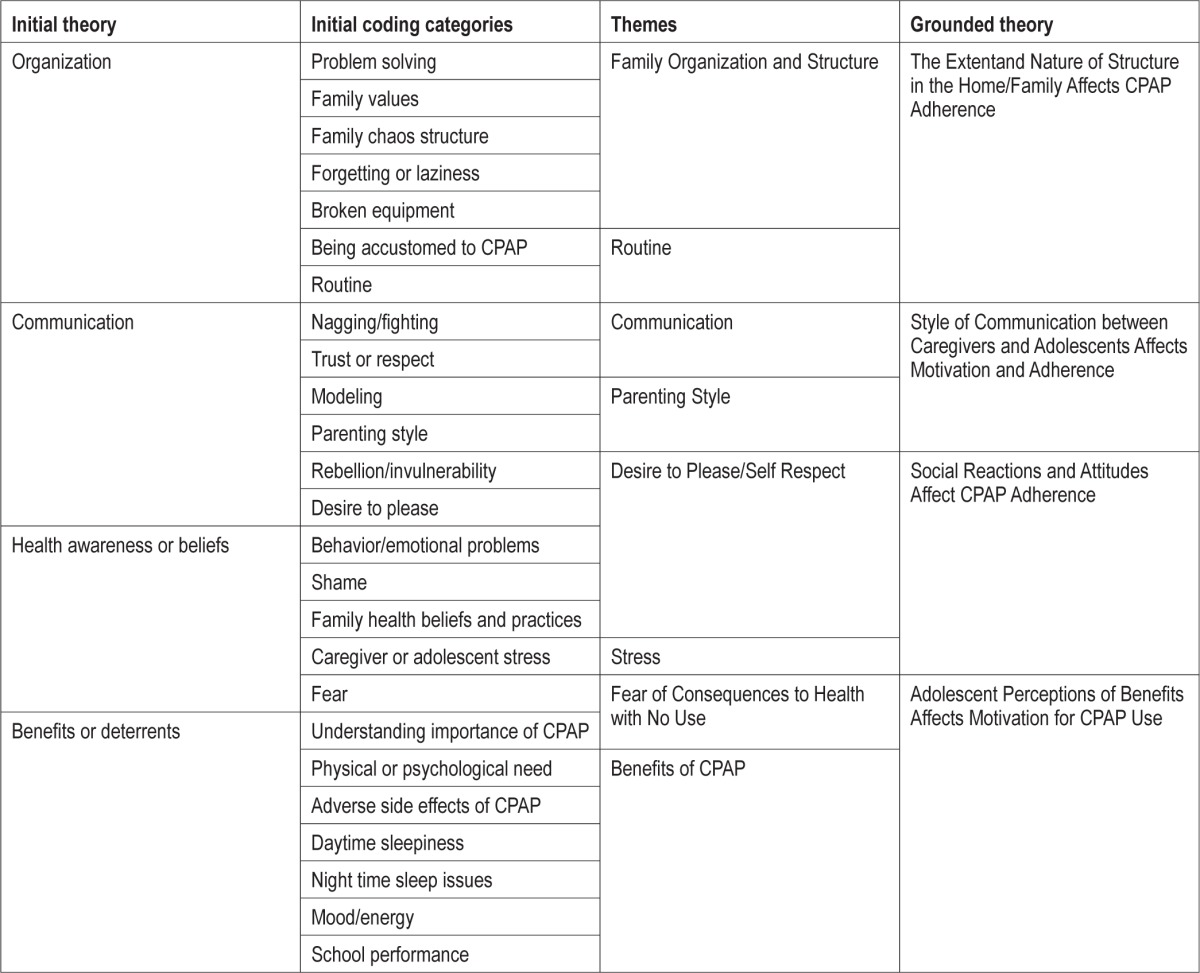

The decision to use modified grounded theory for the analysis16 was made because the framework was created using the researchers' experience and the analysis was inevitably influenced by this experience. Five of the authors read the transcribed text and looked for the factors that had been previously identified as being potentially relevant to CPAP use, as well as allowing other factors to emerge. The authors were conscious of a need to understand the meaning of the responses within the context provided by the participants. In order to facilitate this understanding, interim analyses were informally conducted by the lead investigator and the interviewers after each interview which allowed for the identification of themes to explore in depth in subsequent interviews. We decided to invite for interview all eligible families who attended the sleep center during the study period until we reached saturation (where no new themes were emerging). In order that all the coders had a shared understanding of the concept and context that underpinned each code, we developed what we termed a “codebook” to help insure the integrity and reliability of the coding. Each transcript was independently coded by the 5 authors using NVivo 9.0 software (Doncaster, Victoria), and 85% agreement was found among the coders. Remaining differences in coding were discussed and resolved among the coders. Two authors then refined the factors and categories and created themes and theories (Table 3). These revised themes and theories were reviewed and validated by one of the 5 original coders. Records were kept that demonstrate an audit trail of the data processing and reveal how the theories emerged from the data.

Table 3.

Development of coding, themes, and theories from the initial theories

Objective adherence data from the previous month was obtained from the adolescents' CPAP machines using Encore Pro2 software (Phillips Respironics, Murraysville, PA). In order to explore potential differences between adolescent users, participants were divided into those with high use, low use, and no use based on tertiles of number of minutes used per night. The adherence data was downloaded at the end of the interview and independently reviewed with the adolescent and caregiver, and used to further explore adherence.

RESULTS

Using the departmental CPAP database, 36 families with adolescents who met the eligibility criteria during the study period were approached. 28 (78%) agreed to participate. Seven of these did not come to their study appointments, and thus, 21 adolescents (including one set of twins) were enrolled along with 20 caregivers. Mean CPAP use was 381 ± 80 (SD) (range 213-468) min/night for adolescents with high use (n = 7), 30 ± 24 (range 8-65) min/night for adolescents with low use (n = 7), and zero min/night for adolescents with no use (n = 7).

By comparing adolescents with high, low, and no use, we identified factors associated with CPAP adherence that differentiated use in the groups. This led us to create 4 theories of CPAP use. We postulate that each of the following factors has an effect on CPAP adherence: (1) The extent and nature of structure in the home and family, (2) style of communication between care-givers and adolescents, (3) social reactions and attitudes, and (4) adolescent perception of benefits. Exemplar quotes for each theme can be found in Tables 4–7.

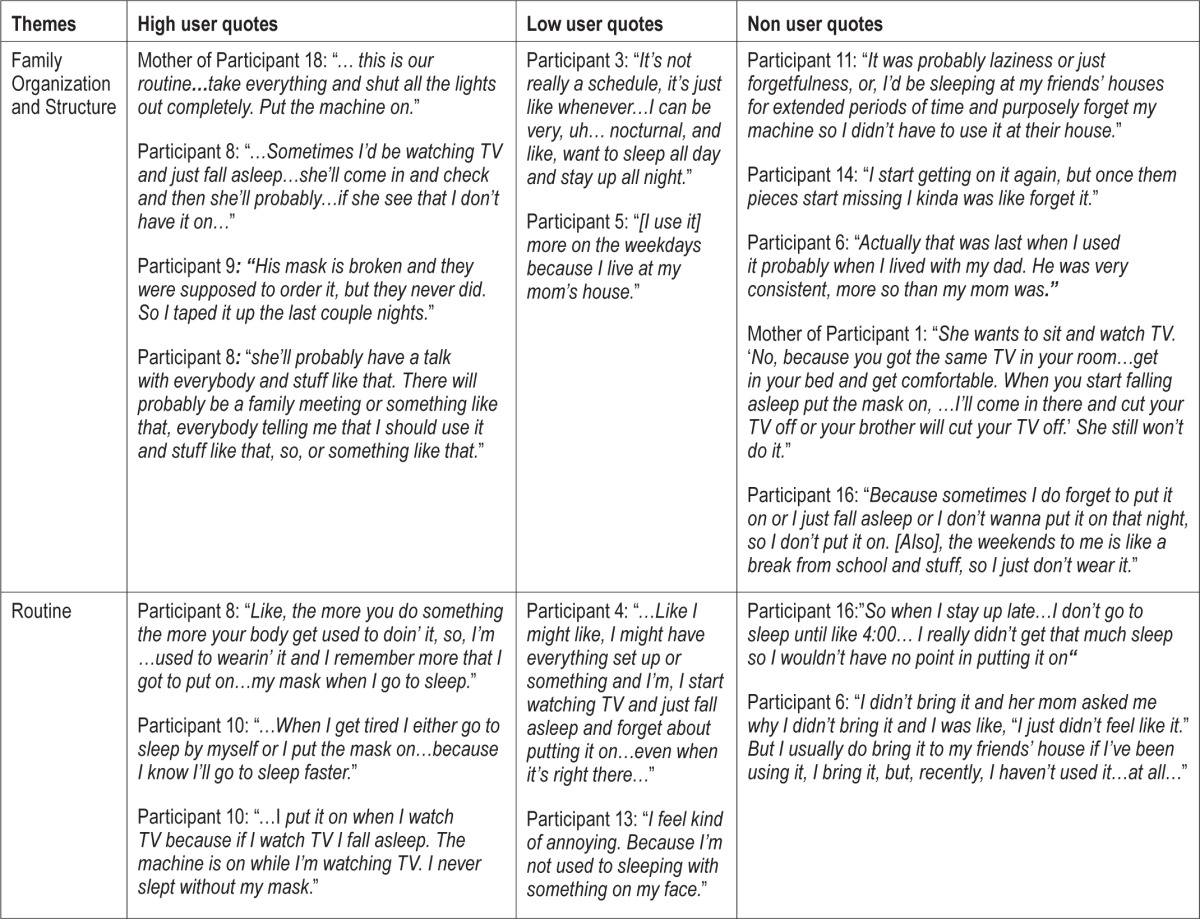

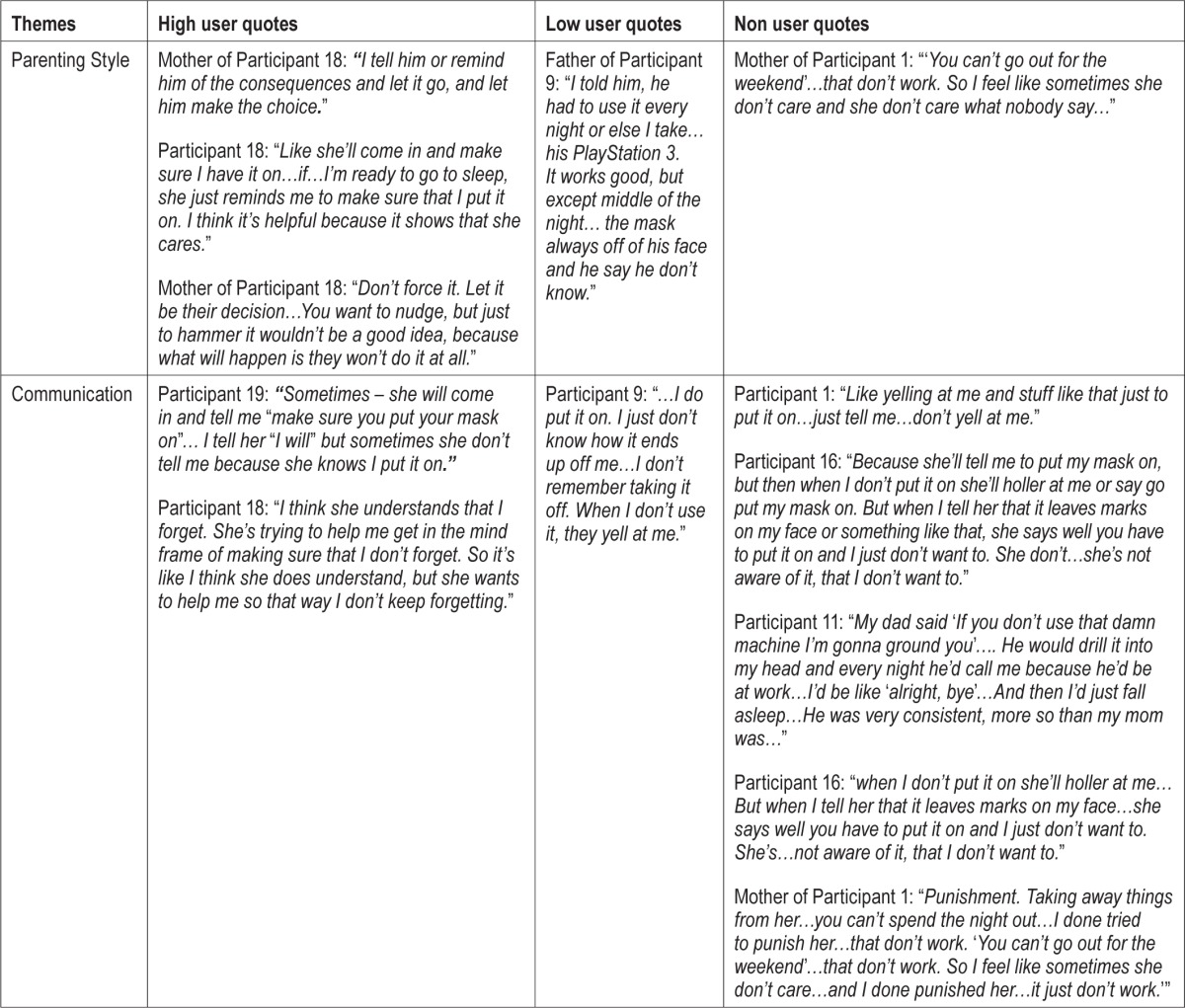

Table 4.

Relationship between quotes, themes and theory: the extent and nature of structure in the home/family affects CPAP adherence

Table 5.

Relationship between quotes, themes and theory: the style of communication between caregivers and adolescents affects CPAP adherence

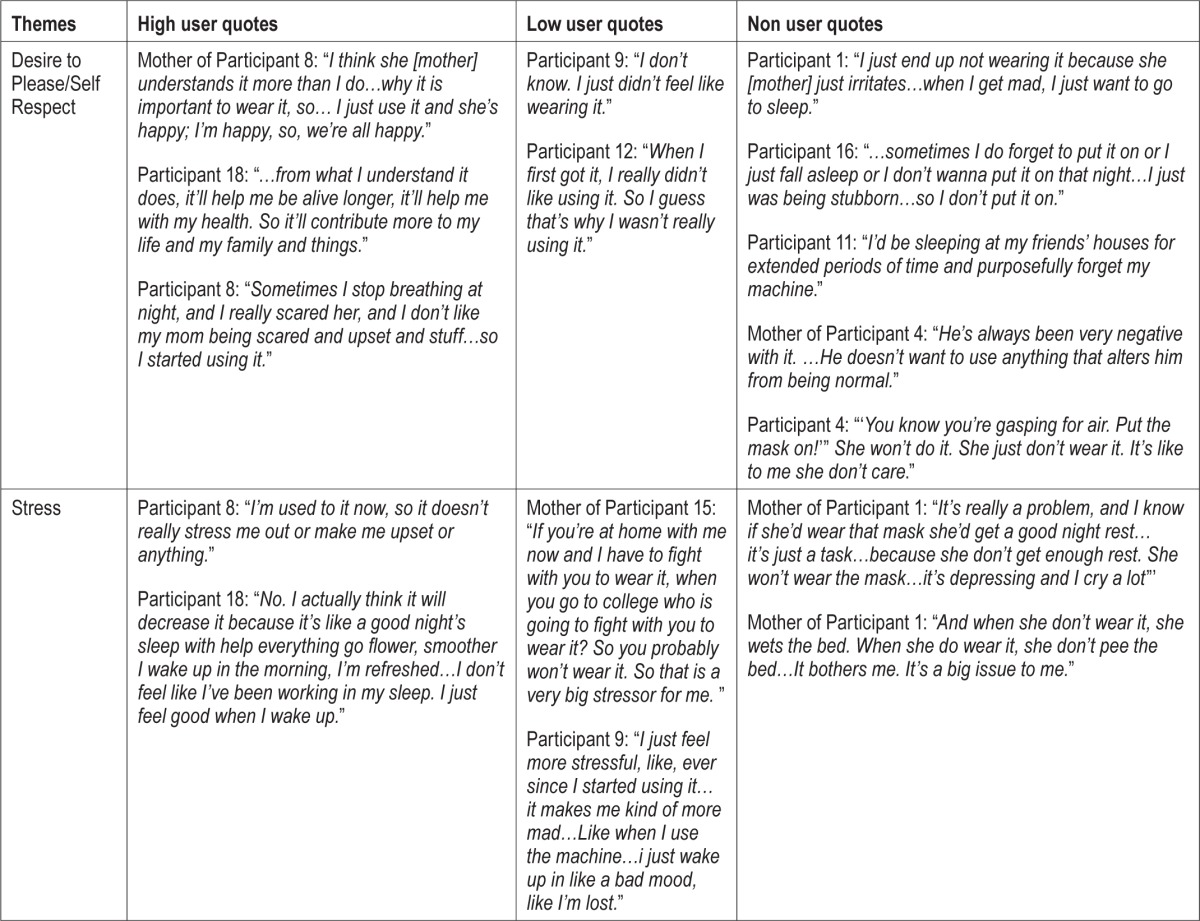

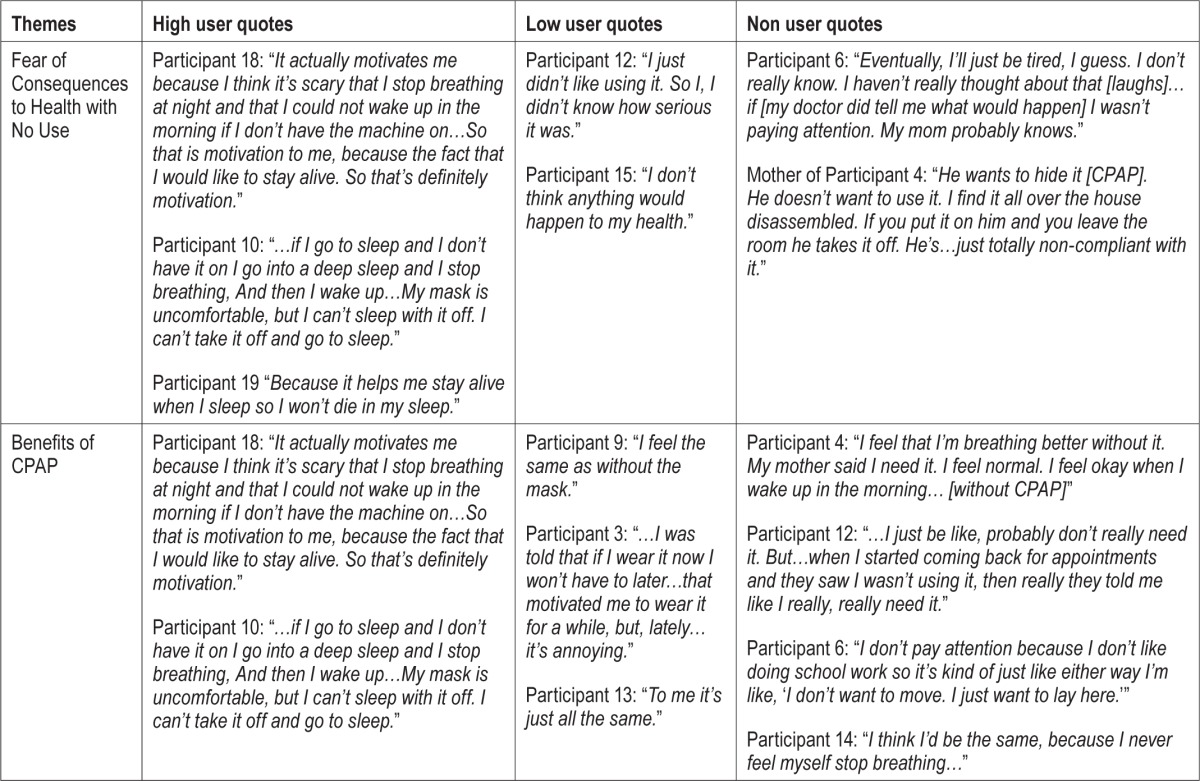

Table 6.

Relationship between quotes, themes and theory: social reactions and attitudes affect CPAP adherence

Table 7.

Relationship between quotes, themes and theory: adolescent perception of benefits affects motivation for CPAP adherence

The Extent and Nature of Structure in the Home/Family Affects CPAP Adherence (Table 4)

Family Organization and Structure

Adolescents with high use described having a stable family structure. Their caregivers were able to organize routines that incorporated CPAP use into their daily lives. When problems occurred, the caregivers were able to identify the issues and work to resolve them, sometimes in creative ways. For example, one participant described how family meetings were used to address concerns.

Routine

Adolescents with low and no use described a lack of stability in their family life, and unsuccessful attempts by their caregivers to incorporate CPAP use into their daily lives. For example, a caregiver felt challenged to create a better nighttime routine to enable her daughter to use her CPAP machine.

Adolescents with high use demonstrated an awareness or knowledge of what is needed for nightly CPAP use. Clearly, having CPAP incorporated into nighttime routines means it is less likely to be forgotten. Adolescents with low or no use described not wanting to use their CPAP machines and deliberately forgetting to use them at night.

Style of Communication between Caregivers and Adolescents Affects CPAP Adherence (Table 5)

Communication

Communication methods about CPAP differed between adolescents with high versus low and no use and their care-givers. Adolescents with high use were not disquieted by their caregivers' reminders to use CPAP. These reminders were appreciated by them and found to be helpful. Consistency was identified as being important by participant 11, who divided her time between different parental homes.

Adolescents with low and no use described that yelling by their caregivers would decrease their motivation for use. They felt that this showed that their caregivers did not understand how difficult it was for the adolescents to use CPAP.

Parenting Style

The caregivers of adolescents with high use described an authoritative parenting style, e.g. explaining why it was important to use CPAP and then giving their adolescents the choice whether to use it or not. Four of 7 of the adolescents with high use have been using the device since they were much younger, less than 10 years old, and are currently using it and cleaning it largely without parental supervision (Table 1).

By contrast, the caregivers of the adolescents with low and no use exemplified an authoritarian parenting style. The quote from the mother of participant 1 typifies this style in her response to asking about strategies used to encourage adherence. Since 13/14 of these adolescents were prescribed CPAP at an older age (> age 10; Table 1), they were initially trusted to use CPAP independently. When caregivers discovered that they had not been using it, caregivers tried to facilitate use by punishment and threats. These scenarios rarely resulted in the adolescent exhibiting the desired behaviors. Indeed, these punishments and threats appeared to have the opposite effect.

Social Reactions and Attitudes Affect CPAP Adherence (Table 6)

Desire to Please/Self-Respect

Within the theme of social reactions and attitudes that affect CPAP adherence, was a sub-theme of desire to please which seemed closely linked to the notion of self-respect. Adolescents with high use revealed an awareness of their caregivers' concerns about their health and the consequences of having sleep apnea. They expressed a desire to alleviate their care-givers' anxiety by using CPAP.

Rebellious attitudes were noted by the caregivers of the participants with low or no use. Parental promotion of CPAP use can become an issue of contention. Within our participants, we found that teenagers who described rebellious attitudes tended to be lower users. Adolescents with low and no use were influenced by their peers' knowledge of them having a CPAP machine. These users appeared to be ashamed about having to use CPAP and expressed wanting to be like peers. Their desire to conform to peer norms was also noted by caregivers.

Some participants did not express any need to use CPAP. A sub-theme of invulnerability was related to the theme of adolescent perception of benefits affects motivation. This feeling of invulnerability in the adolescents was recognized by their care-givers too.

Stress

Stress within a family was linked to CPAP use. High use appeared to decrease stress. While adolescents with low and no use did not perceive lack of CPAP adherence to be an issue related to stress, adolescents' lack of use was seen as a factor in increasing the stress in the lives of the caregivers.

Adolescent Perception of Benefits Affects Motivation for CPAP Adherence (Table 7)

Fear of Consequences to Health with No Use

Adolescents with high use seemed to be motivated by fear of the consequences of not using CPAP. Adolescents with low and no use appeared indifferent to the knowledge of the consequences of not using CPAP. They expressed indifference about their lack of use being detrimental to their health.

Benefits of CPAP

Adolescents with high use consistently described receiving benefits from CPAP use. They appeared to be untroubled by the adverse side effects they suffered. However, adolescents with low and no use were more variable in noticing benefits from CPAP, which may have been due to inconsistent use. They complained about discomfort and saw this as a reason for disuse.

Review of CPAP Downloads with Participants

In adolescents with low and no use, being shown evidence of their lack of use provoked surprise. The low use participants were especially astonished about their lack of use. Their expressions showed a belief that they thought they had been using their CPAP machines more. Participant 12 said, “I like I had the machine set up …So I guess I was using it and I take it off when I was asleep.” Participant 15 said, “I usually would think that I would have it on long, but then I see it don't look like I have it on that long at all.”

Caregivers expressed surprise and concern when presented with the evidence of low or no use. The mother of participant 13 responded that she thought her daughter was using her CPAP machine most nights. After seeing the download of her daughter's CPAP use during the past month, she said “She has to use it more, …I'm gonna stay on top of it.”

DISCUSSION

Little is known about the perspectives of adolescent CPAP users and their caregivers. This is important as adherence in this age group is often poor. Gaining these insights may be of benefit to clinicians in identifying factors to explore with adolescent patients and their families to facilitate optimal use.

The Extent and Nature of Structure in the Home/Family Affects CPAP Adherence

Adolescents may have difficulty adhering to treatment regimens devised by health professionals and parents because of poorly developed abstract thinking. This problem may manifest as a poor ability to plan and prepare for different situations using abstract concepts17; therefore, family organization is key. Bender found in a quantitative study that non-adherence, to β-agonists and corticosteroids in 24 asthmatic children, increased with the level of disorganization or dysfunction within the family.18 Our qualitative results support this conclusion with CPAP adherence: for families of adolescents with high use, CPAP use was considered an important family priority by both the caregivers and the adolescents. Also, households with an adolescent with high use maintained an organized structure for managing CPAP use, e.g., caregiver present at bedtime and facilitating the adolescents using CPAP away from home.

Youth with behavior problems are especially at risk for poor adherence. According to family process theories, behaviorally disordered youth tend to lack routines in their lives, which is hypothesized to compromise their compliance with a daily, multifaceted treatment regimen.19 Greening found it is important that clinicians help families recognize the critical aspects of the child's medical regimen and to integrate the treatment plan into the child's and family's current routine activities.20 If a routine does not exist, it may be beneficial for the clinical team to facilitate the development of a routine with the family that incorporates CPAP.

Style of Communication between Caregivers and Adolescents Affects CPAP Adherence

Starting in early adolescence, parents and adolescents begin to have less interactions and spend less time together outside the home than they did previously and children's conformity to their peers peaks, reflecting the importance of social acceptance.21 This distancing in parent-adolescent relations has a functional value for adolescents in that it fosters their independence, prompts them to try more things on their own, and develops their sense of efficacy.22 Caregivers may view their adolescents as emerging adults and may expect their adolescent to use CPAP independently without support and supervision. Of note, most high users initiated CPAP during childhood rather than adolescence, when their parents may have played a more active role.

Parenting style can contribute to adolescent adherence patterns. Family environments that encourage autonomy and the early adolescent's role in family decision making are associated with self-esteem, self-reliance, satisfaction with school and student-teacher relations, positive school adjustment, and advanced moral reasoning.23 Recognizing the emerging adult autonomy of an adolescent is a factor that can contribute to optimal use by encouraging a sense of self-respect and self-discipline and fostering mature and responsible health decision-making. Conversely, a parenting style that is coercive, authoritarian, and not attuned to the adolescent's need for autonomy and input is associated with self-consciousness and lowered self-esteem which can have negative implications for CPAP adherence.24

Research from several investigators25–27 suggests that adolescents' relationships with their parents can be also be stressful during early and middle adolescence due to developmental changes. This stress is often focused on issues of control and autonomy within the family, which are renegotiated during this developmental period. Ideally, the renegotiation process would be a smooth transition for both adolescents and parents, but as children mature and take more responsibility for their own lives; it is not easy for parents to determine the optimal level of autonomy versus control. According to the stage-environment fit perspective, one would predict strained relationships wherever there is a poor fit between the child's desire for increasing autonomy and the opportunities for independence and autonomy provided by the child's parents.28

Monaghan found that an authoritative parenting style was associated with significantly less parenting stress than authoritarian or permissive parenting styles.29 In our study, an authoritative parenting style was more common among caregivers of adolescents with high use and an authoritarian style was more likely to be demonstrated by caregivers of no and low use adolescents. Our findings were consistent with studies of other treatment regimens which found that caregivers with an authoritative parenting style were associated with improved treatment adherence.30–32 For adolescents with low and no use, there were some caregivers who would try to assist with using CPAP, but their authoritarian parenting style led them to have expectations that were unrealistic resulting in little or no CPAP use. This phenomenon has described in the literature as “Miscarried Helping.”33 DiMatteo also found that social support from caring family members, family cohesiveness, and positive family interaction patterns strongly affect adherence. Conversely, family conflict and negative feelings in the family can serve as powerful factors related to non-adherence, as well as by being upsetting and stressful.34 Effective communication is important in the parental promotion of CPAP adherence.

Offering occasional reminders and checking on adolescents at bedtime as a means of encouraging the establishment of CPAP into their routines seems to promote adherence. Berating or nagging appeared to have the opposite effect than intended.

There was a difference in the age CPAP was prescribed between the high users and low and no users (Table 1). We believe this shows the difficulty of introducing CPAP in the adolescent age group. Introducing CPAP prior to adolescence, when children's behaviors are more malleable and parents have greater influence and control,28 is likely to be less challenging, although can still take time for the child to become accustomed to using the mask and machine. When CPAP is prescribed at a younger age, there is a longer opportunity for it to become a routine part of the adolescent's life and the patient may have a better sense of the benefits of use. Introducing CPAP use during adolescence may be especially challenging because of rebellion and emerging autonomy, as discussed below.

Social Reactions and Attitudes Affect CPAP Adherence

Concerns about health contributed to stress levels in participants' families. Although high stress levels in the families of low and no users may not have been entirely attributable to poor adherence, poor CPAP use was a cause of stress for the caregivers. Becoming aware of family stressors is important so that the health care providers consider the social situation of the families to begin the conversation that despite having other stresses how can they best support the family in using CPAP and making its use a priority. The way CPAP is initiated may be important to facilitate adherence. Adding CPAP to a family that is already coping with significant stressors may only magnify stress in the household and impede actual use of CPAP.

Some high users attributed the reasons for their regular use of CPAP to a desire to please their caregivers. They expressed concern about their parents' anxiety about their OSAS and did not want to upset them. They seemed to have a greater sense of self-worth than the low and no users and had a sense of responsibility for their own and their parents' well-being. Encouraging self-respect and fostering a sense of responsibility would appear to be a helpful strategy for increasing adherence.

The participant-caregiver relationship also appeared to play a role in adherence. Within the high users, most participants described cohesive family relationships. Although a close relationship with the parent facilitates adherence in young adolescents, if the parent is overprotective, it may prove challenging for the adolescent to achieve autonomy and assume responsibility for their CPAP use. Overprotection has been shown to cause social isolation and interfere with the development of individual ability for self-care.35

A normal facet of adolescence is to rebel against authority and to challenge limits set by family caregivers. One of the main tasks of adolescence is to become an autonomous individual. The drive for autonomy stems from biological processes marking the transition to a more adult role (puberty and increasing cognitive maturity) and from shifts in social roles and expectations. As adolescents become physically mature, they begin to question family rules and roles, leading to conflicts.21 CPAP use provides an opportunity for rebellion. While adolescents may rebel against parental and adult societal expectations, they want to conform to peer norms.

Another aspect of the developmental process is a feeling of invulnerability. Adolescents possess little ability to appreciate consequences of current life style decisions and actions. They see themselves as being invulnerable, a notion that has been described in the literature as being “bullet proof.”17 This notion is linked to the adolescent perceptions of the benefits of CPAP.

Adolescent Perception of Benefits Affect Motivation for CPAP Adherence

Less daytime sleepiness, sleeping better, having more energy, improved school performance, and decrease in enuresis were some of the benefits associated with adolescent CPAP adherence. Caregivers and adolescents of the low and no CPAP use groups reported more subtle benefits from using CPAP than their high use counterparts. Some of the adolescents with high use described having a physical or psychological need for using CPAP, e.g., believing it was what made them fall asleep or reporting they would wake up choking and gasping if they fell asleep without using it. Having an understanding of the importance of using CPAP was associated with high use, which highlights the need for healthcare providers to educate CPAP users and their families as fully as possible about the purpose and benefits of CPAP, as well as the physical and neurobehavioral consequences of untreated OSAS.

Discomfort with using CPAP was described by all the adolescents, but only adolescents in the low and no use groups described this as a significant barrier to adherence. Nasal congestion, skin irritation, a poor mask fit, and intolerance to air pressure are all well-known side effects of CPAP use that were mentioned by all the adolescents. As part of the educational initiation processes for CPAP, it is essential to provide anticipatory guidance about the potential complications of CPAP. Further, it is important for clinicians to explain that potential remedies exist for these complications and that the family should contact the medical team if the adolescent experiences any of the side effects. While some of these complications may improve with increased use of CPAP, others may be addressed by the health care team (e.g., mask fit, chronic nasal congestion, skin irritation). Identifying potential barriers and providing support to problem solve barriers may facilitate adherence.

As previously discussed, some adolescents are non-adherent because of a feeling of invulnerability; however, the adolescents with high use described fear as a motivator for adherence. They expressed being afraid of the consequences of not using CPAP (e.g. death, not being able to breathe, adverse effects on their hearts). Bond et al.'s Health Belief Model predicted that the benefits-costs and cues constructs were related to compliance if benefits were high and costs were low. The greatest compliance was achieved with low perceived threat and high perceived benefits-costs. Our findings fit this model. High use adolescents expressed knowledge of fear of consequences, or high threat, for lack of use and had a perception of high benefits and low cost regarding their CPAP use. Adolescents with low or no use perceived low benefit, high cost, and high threat, but the level of threat was not adequate motivation to overcome the high cost of use which may be linked to the adolescent perception of invulnerability.36

Strengths and Limitations

This was a small study and as is the case with qualitative research, the findings do not presume to be generalizable. Rather, we have generated grounded theories that we offer for further exploration and evaluation. Nonetheless, we feel that these theories merit consideration by clinicians in helping families develop strategies that will promote CPAP use. Despite purposively sampling across the spectrum of adherence, we do recognize it was not demographically representative, and the population was primarily inner city families. Following the analysis, it became apparent there was a difference in the age at which CPAP was prescribed for the high users (Table 1); ideally, we should have also purposively recruited more high users who started CPAP during adolescence and additional low and no users who were prescribed CPAP at a younger age in order to represent a broader range of experience using CPAP in adolescence. Another potential weakness that is common to all studies involving interviewing was self-selection of participants, which could create volunteer bias in our sample. There is a risk that participants will offer responses that they feel are desired by the interviewer. We attempted to minimize this risk by carrying out the interviews in a non-judgmental and open way and by emphasizing that there were no right or wrong answers and that the interviewer was genuinely interested in the participants' experiences and opinions.

Our findings were strengthened by the use of objective adherence data facilitating an open discussion about actual use. Objective measurement of adherence is less prone to bias, owing to the tendency of parents and children to overestimate adherence on self-report.37

CONCLUSION

Adherence to medical regimens in adolescents has long been recognized as problematic. For sleep clinicians, CPAP adherence in adolescents has been a concern that is likely to grow due to the current obesity epidemic and an increase in referrals to sleep specialists of adolescents with OSAS. Understanding the adolescent and family experience of using CPAP may be the key to developing more effective mechanisms to promote adherence. Issues that need to be considered are parenting style, family dynamics, and communication. Health education, combined with family involvement in developing strategies that facilitate CPAP use within their family context, are important components of promoting adherence. Since many adolescents appear reluctant to make their peers aware of their CPAP use, peer support groups may help promote adherence. All support strategies need to take into account the developmental process of adolescence and should be tailored to the individual and his or her family.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Carole Marcus, Jill Maggs, Mary Anne Cornaglia, and Ruth Bradford have research support in the form of loaned equipment from Philips Respironics and Ventus, not related to the current study. Nicolas Stettler works at a scientific consulting firm that does work for various companies. None of his work has been related to the topic of this study or devices described in it. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest. Financial Support: NIH T32-HL007713-19 & R01HL58585

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Reneé H. Moore from the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Pennsylvania for her assistance with the study design and mentorship; Shimrit Keddem and Katie Kellom from the Mixed-Methods Research Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania for their expertise with NVivo 9.0 software; and the patients and their families for their participation in the study. Financial Support: NIH T32-HL007713-19 & R01HL58585

REFERENCES

- 1.Redline S, Tishler PV, Schluchter M, Aylor J, Clark K, Graham G. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in children. Associations with obesity, race, and respiratory problems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1527–32. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9809079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcus CL, Carroll JL, Koerner CB, Hamer A, Lutz J, Loughlin GM. Determinants of growth in children with the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Pediatr. 1994;125:556–62. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guilleminault C, Eldridge FL, Simmons FB, Dement WC. Sleep apnea in eight children. Pediatrics. 1976;58:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, et al. Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: An American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing In Collaboration With the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Center on Sleep Disorders Research (National Institutes of Health) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:686–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beebe DW, Byars KC. Adolescents with obstructive sleep apnea adhere poorly to positive airway pressure (PAP), but PAP users show improved attention and school performance. PLoS One. 6:e16924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beebe DW, Ris MD, Kramer ME, Long E, Amin R. The association between sleep disordered breathing, academic grades, and cognitive and behavioral functioning among overweight subjects during middle to late childhood. Sleep. 2010;33:1447–56. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.11.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zitelli BJ, Davis HW. Atlas of pediatric physical diagnosis. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcus CL, Rosen G, Ward SL, et al. Adherence to and effectiveness of positive airway pressure therapy in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e442–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcus CL, Beck SE, Traylor J, et al. Randomized, double-blind clinical trial of two different modes of positive airway pressure therapy on adherence and efficacy in children. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:37–42. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawyer AM, Deatrick JA, Kuna ST, Weaver TE. Differences in perceptions of the diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure therapy among adherers and nonadherers. Qual Health Res. 2010;20:873–92. doi: 10.1177/1049732310365502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon SL, Duncan CL, Janicke DM, Wagner MH. Barriers to treatment of paediatric obstructive sleep apnoea: Development of the adherence barriers to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) questionnaire. Sleep Med. 2012;13:172–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orrell-Valente JK, Jarlsberg LG, Hill LG, Cabana MD. At what age do children start taking daily asthma medicines on their own? Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1186–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chigier E. Compliance in adolescents with epilepsy or diabetes. J Adolesc Health. 1992;13:375–9. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Difeo N, Meltzer LJ, Beck SE, et al. Predictors of positive airway pressure therapy adherence in children: a prospective study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:279–86. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charmaz K. Grounded theory: objectivist and constructivist methods. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The handbook of qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. pp. 509–35. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suris JC, Michaud PA, Viner R. The adolescent with a chronic condition. Part I: developmental issues. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:938–42. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.045369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bender B, Milgrom H, Rand C, Ackerson L. Psychological factors associated with medication nonadherence in asthmatic children. J Asthma. 1998;35:347–53. doi: 10.3109/02770909809075667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiese BH, Tomcho TJ, Douglas M, Josephs K, Poltrock S, Baker T. A review of 50 years of research on naturally occurring family routines and rituals: Cause for celebration? J Fam Psychol. 2002;16:381–90. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greening L, Stoppelbein L, Konishi C, Jordan SS, Moll G. Child routines and youths' adherence to treatment for type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:437–47. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eccles JS. The development of children ages 6 to 14. Future Child. 1999;9:30–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins WA. Parent-child relationships in the transition to adolescence: Continuity and change in interaction, affect, and cognition. In: Montemayor R, Adams GR, Gullotta TP, editors. From childhood to adolescence: A transitional period? Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. pp. 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eccles JS, Lord S, Buchanan CM. School transitions in early adolescence: What are we doing to our young people? In: Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen AC, editors. Transitions through adolescence: Interpersonal domains and context. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. pp. 251–84. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leahy RL. Parental practices and the development of moral judgment and self-image disparity during adolescence. Dev Psychol. 1981;17:580–94. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buchanan CM, Eccles JS, Becker JB. Are adolescents the victims of raging hormones? Evidence for activational effects of hormones on moods and behavior at adolescence. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:62–107. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paikoff RL, Brooks-Gunn J. Do parent-child relationships change during puberty? Psychol Bull. 1991;110:47–66. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinberg L. Interdependence in the family: Autonomy, conflict, and harmony in the parent-adolescent relationship. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 255–76. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eccles JS, Midgley C, Wigfield A, et al. Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents' experiences in schools and in families. Am Psychol. 1993;48:90–101. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monaghan M, Horn I, Alvarez V, Cogen F, Streisand R. Authoritative parenting, parenting stress, and self-care in pre-adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Psychol Medical Settings. 19:255–61. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9284-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhee H, Wenzel J, Steeves RH. Adolescents' psychosocial experiences living with asthma: a focus group study. J Pediatr Health Care. 2007;21:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.George M, Rand-Giovannetti D, Eakin MN, Borrelli B, Zettler M, Riekert KA. Perceptions of barriers and facilitators: Self-management decisions by older adolescents and adults with CF. J Cyst Fibros. 2010;9:425–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guilfoyle SM, Goebel JW, Pai ALH. Efficacy and flexibility impact perceived adherence barriers in pediatric kidney post-transplantation. Fam Syst Health. 2011;29:44–54. doi: 10.1037/a0023024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carden SR. Working with Families of Adolescents with Diabetes, CME Disclosures. Presented at the 60th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association 2000; San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 34.DiMatteo MR. The role of effective communication with children and their families in fostering adherence to pediatric regimens. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:339–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wysocki T. Diabetes mellitus in the transition to adulthood: adjustment, self-care, and health status. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1992;13:194–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bond GG, Aiken LS, Somerville SC. The health belief model and adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Health Psychol. 1992;11:190–8. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bender BG, Bartlett SJ, Rand CS, Turner C, Wamboldt FS, Zhang L. Impact of interview mode on accuracy of child and parent report of adherence with asthma-controller medication. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e471–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]