Abstract

IDH1 and IDH2 (Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 and 2) mutants are common in several cancers, including leukemias, and overproduce the (R)-enantiomer of 2-hydroxyglutarate [(R)-2-HG]. Elucidating the role of IDH mutations and (R)-2-HG in leukemogenesis has been hampered by a lack of appropriate cell-based models. Here we show that a canonical IDH1 mutant, IDH1 R132H, promotes cytokine-independence and blocks differentiation in hematopoietic cells. These effects can be recapitulated by (R)-2-HG, but not (S)-2-HG, despite the fact that (S)-2-HG more potently inhibits enzymes previously linked to the pathogenesis of IDH mutant tumors, such as TET2 (Ten Eleven Translocation 2). We provide evidence that this paradox relates to the ability of (S)-2-HG, but not (R)-2-HG, to inhibit the EglN (Egg-laying Defective Nine) prolyl hydroxylases and, importantly, show that transformation by (R)-2-HG is reversible.

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is caused by somatic genetic mutations that deregulate hematopoietic cell proliferation and differentiation. In many cases of AML the responsible genetic abnormalities are chromosomal translocations involving key transcription factors, epigenetic regulators and mediators of cell signaling. However, no translocations are detected in 40% of cases of AML (1). In such cases of ‘normal cytogenetic’ AML (NC-AML) the pathogenic driver mutations are largely unknown.

Recent genomic sequencing efforts, however, have identified a number of recurrent mutations in NC-AML that might contribute to leukemogenesis, including mutations in Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 and 2 (IDH1 and IDH2) (2). IDH1 and IDH2 are key metabolic enzymes that convert isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate [also called 2-oxoglutarate (2-OG)], which is an essential cofactor for 2-OG-dependent dioxygenases. These enzymes are linked to diverse cellular processes such as adaptation to hypoxia, histone demethylation and DNA modification (3). Cancer-associated IDH mutants convert 2-OG to the (R)-enantiomer of 2-hydroxyglutarate [(R)-2-HG] (4, 5). Both the (R)- and (S)-enantiomers of 2-HG are structurally similar to 2-OG and can inhibit many 2-OG-dependent enzymes in vitro and in vivo (6-8). In the case of the EglN (Egg-laying defective Nine) prolyl hydroxlases that downregulate the HIF (Hypoxia-inducible Factor) transcription factor, however, (R)-2-HG potentiates, while (S)-2-HG inhibits, EglN activity (8). Mutant IDH is therefore widely believed to transform cells by modulating the behavior of specific 2-OG-dependent enzymes. Nonetheless, IDH mutations induce a number of metabolic abnormalities in addition to (R)-2-HG accumulation (9), and it has not yet been formally proven that (R)-2-HG is sufficient to transform cells. Deciphering the pathogenic roles of mutant IDH and (R)-2-HG in leukemia has been particularly problematic due to the lack of IDH mutant leukemic cell lines and the lack of robust cell-based assays with which to monitor hematopoietic transformation by mutant IDH and (R)-2-HG.

To address this latter deficiency, we stably infected the TF-1 human erythroleukemia cell line with lentiviral vectors encoding hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged versions of wild-type IDH1, a tumor-derived mutant (IDH1 R132H), or an IDH1 R132H variant in which three conserved aspartic acid residues within the IDH1 catalytic domain were replaced with asparagines (R132H/3DN) (Fig. 1A). This leukemic line is unusual insofar as it is cytokine-dependent (GM-CSF) and retains the ability to differentiate in response to erythropoietin (EPO) (10).

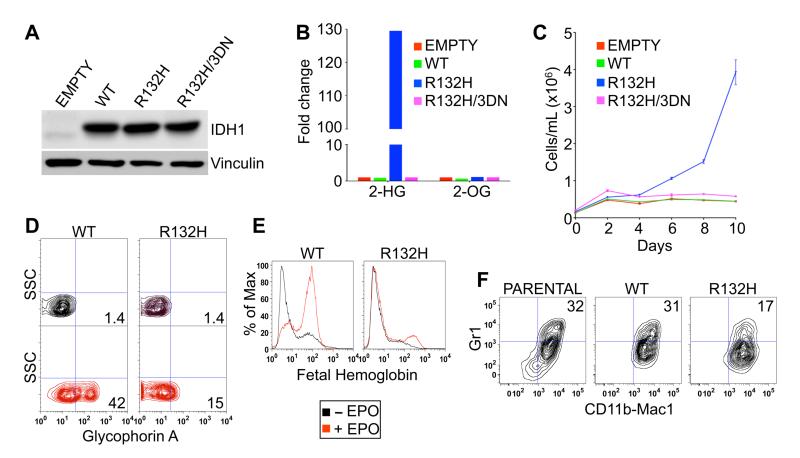

Fig. 1.

IDH1 R132H leukemic transformation assays. (A and B) Immunoblot (A) and LC-MS (B) analysis of TF-1 cells infected with lentiviruses encoding GFP alone (empty) or GFP and the indicated IDH1 variants. Shown are mean LC-MS values of triplicate experiments. (C) Proliferation of TF-1 cells described in (A) and (B) under cytokine-poor conditions. Shown are mean values of duplicate experiments ± SD. (D and E) Erythroid differentiation of parental TF-1 cells and derivatives described in (A) and (B) as determined by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) for Glycophorin A (D) or fetal hemoglobin (E) after 8 days of EPO treatment. (F) Differentiation of parental SCF ER-Hoxb8 cells and derivatives expressing the indicated IDH1 variants as determined by dual staining for CD11b/Mac1 and Gr1 3 days after withdrawal of β-estradiol. FACS plots shown are representative results of three independent experiments.

As expected, 2-HG levels were dramatically increased in cells producing IDH1 R132H but not in cells producing wild-type IDH1 or the catalytically inactive R132H/3DN variant (Fig. 1B). In multiple independent experiments, TF-1 cells expressing IDH1 R132H became cytokine-independent 12-16 days (4 passages) after infection (Fig. 1C). In contrast, parental TF-1 cells spontaneously became cytokine-dependent, but with a much longer and more variable latency. Furthermore, after 10 passages in culture, IDH1 R132H-expressing TF-1 cells, in contrast to the control cells, no longer differentiated in response to EPO (Fig. 1D-1E and fig. S1). Thus expression of mutant IDH in TF-1 cells promotes two hallmarks of leukemic transformation – growth factor-independence and impaired differentiation. Of note, IDH1 R132H impaired the fitness of TF-1 cells grown in the presence of GM-CSF despite conferring a proliferative advantage to TF-1 cells in the absence of GM-CSF (Fig. 1C and fig. S2). Consistent with this observation, IDH1 R132H expression was attenuated in TF-1 cells after repeated passaging in the presence of GM-CSF (fig. S3).

To confirm that the inhibitory effect of mutant IDH on hematopoietic differentiation is not restricted to TF-1 cells, we stably infected SCF (Stem Cell Factor) ER (Estrogen Receptor)-Hoxb8 cells, which are granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells derived from primary murine bone marrow cells immortalized with a conditional oncogene (11), with viruses encoding wild-type IDH1 and IDH1 R132H (fig. S4). In the presence of estrogen these cells express a functional ER-Hoxb8 fusion protein that promotes their survival and proliferation. Upon estrogen withdrawal, the cells differentiate and upregulate expression of the monocytic markers CD11b/Mac1 and Gr1. Expression of IDH1 R132H in SCF ER-Hoxb8 cells, however, blunted their differentiation in response to estrogen withdrawal (Fig. 1F).

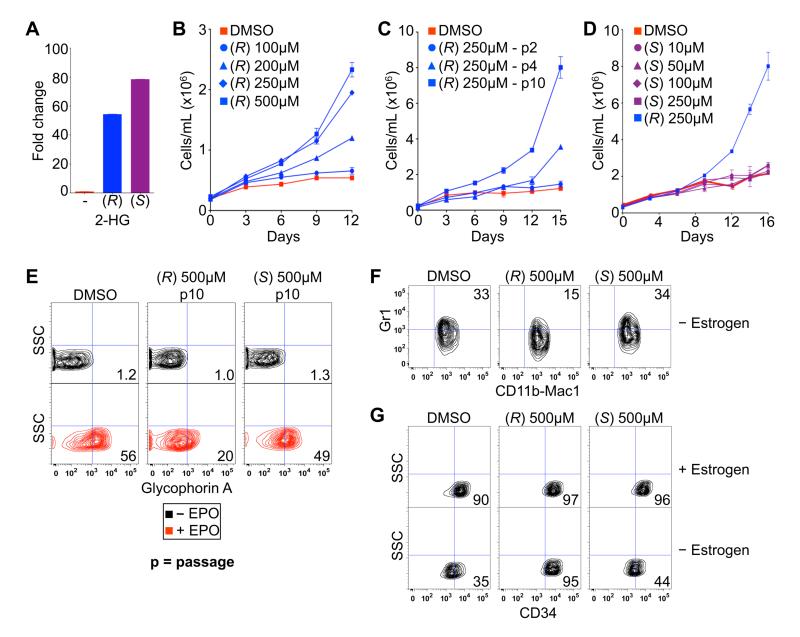

To ask whether the effects of IDH1 R132H on TF-1 cells are mediated by (R)-2-HG, we treated TF-1 cells with vehicle (DMSO) or cell membrane-permeable [TFMB (trifluoromethyl benzyl)-esterified] versions of either (R)-2-HG or (S)-2-HG. Measurement of intracellular 2-HG levels in treated TF-1 cells confirmed that the esterified 2-HG enantiomers were equally cell-permeable (Fig. 2A). TF-1 cells passaged in the presence of TFMB-(R)-2-HG became growth factor-independent and no longer differentiated in response to EPO (Fig. 2B and 2E). Promotion of growth factor-independence and loss of EPO-responsiveness by TFMB-(R)-2-HG was dose-dependent (Fig. 2B and fig. S5) and passage-dependent (Fig. 2C and fig. S5). In stark contrast, TFMB-(S)-2-HG did not promote cytokine-independence or block differentiation at any concentration or time point tested (Fig. 2D and 2E). Likewise, treatment of SCF ER-Hoxb8 cells with TFMB-(R)-2-HG, but not TFMB-(S)-2-HG, impaired their differentiation in response to estrogen withdrawal, as determined by decreased expression of Gr1 and persistent expression of the stem cell markers CD34 and c-kit (Fig. 2F-2G, and fig. S6). Thus, (R)-2-HG, but not (S)-2-HG, promotes leukemic transformation. Of note, absolute quantification of (R)-2-HG levels in TF-1 cells transformed by expression of IDH1 R132H or by treatment with TFMB-(R)-2-HG confirmed that the intracellular 2-HG concentrations achieved in both settings approximate those found in IDH mutant neoplasms in patients (low mM) (fig. S7) (12, 13). The accumulation of 2-HG to these high levels in cells treated with 250-500 μM TFMB-(R)-2-HG suggests that the free 2-HG liberated from the ester by intracellular esterases disappears more slowly than TFMB-(R)-2-HG enters the cells.

Fig. 2.

(R)-2-HG is sufficient to promote leukemogenesis. (A) LC-MS analysis of TF-1 cells after treatment for 3 hours with DMSO (-) or 250 μM of the indicated esterified (TFMB) 2-HG. Shown are mean values of triplicate experiments. (B-D) Proliferation of TF-1 cells under cytokine-poor conditions in the presence of the indicated amounts of TFMB-(R)-2-HG (B and C) or TFMB-(S)-2-HG (D). Cells in (B and D) were passaged 10 times prior to GM-CSF withdrawal. Cells treated with 250 μM TFMB-(R)-2-HG are also included in (D) for comparison. Shown are mean values of duplicate experiments ± SD. (E) Differentiation of TF-1 cells, as determined by Glycophorin A FACS, after 8 days of EPO treatment following pretreatment for 10 passages with DMSO or 500 μM TFMB-2-HG (R or S). Shown are representative results of three independent experiments. (F and G) Differentiation of SCF ER-Hoxb8 cells, as determined by dual staining for CD11b/Mac1 and Gr1 (F) or staining for CD34 (G), 3 days after of withdrawal of β-estradiol following pretreatment with DMSO or 500 μM TFMB-2-HG (R or S) for 20 passages. Shown are representative results of two independent experiments.

To begin to understand how (R)-2-HG promotes leukemic transformation we next infected parental TF-1 cells with a pool of lentiviral shRNA vectors targeting all the known 2-OG-dependent dioxygenases (4-8 shRNAs/enzyme) (Table S1), cultured the cells in the absence of GM-CSF, and monitored the abundance of the individual shRNA vectors by next-generation DNA sequencing. We reasoned that the enzymes targeted by shRNAs that were significantly enriched over time (because, for example, those shRNAs confer cytokine-independence) would, if also inhibited by (R)-2-HG at concentrations observed in leukemic cells, contribute to transformation by (R)-2-HG. One of the top scoring enzymes from this screen was TET2 (Ten Eleven Translocation 2), which is mutationally inactivated in a subset of AML and has recently been suggested to be pathogenic target of mutant IDH (Fig. 3A) (14, 15). In contrast, the TET2 paralog TET1 did not score in our screen (Fig. 3A).

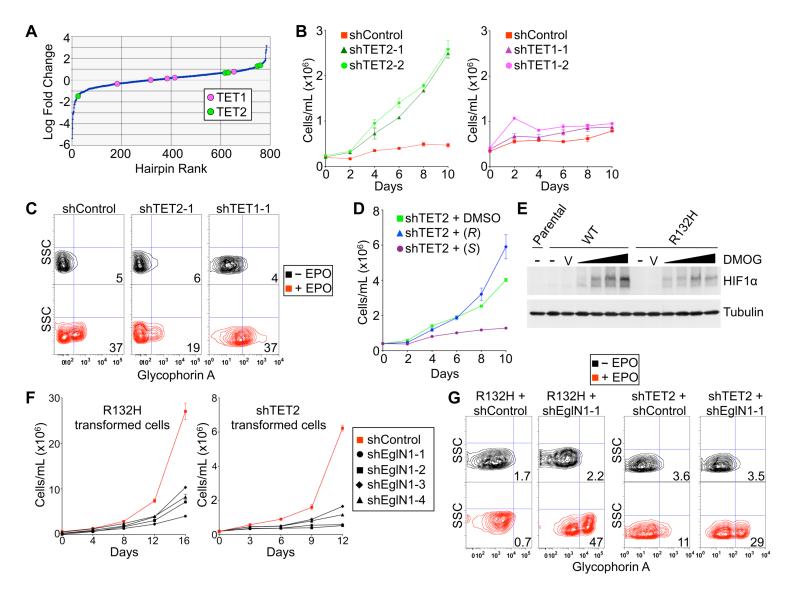

Fig. 3.

Opposing roles of TET2 and EglN1 in TF-1 cell transformation. (A) Relative enrichment/depletion of shRNAs targeting TET2 or TET1 in TF-1 cells infected with a pool of ~800 lentiviral shRNAs vectors targeting 2-OG-dependent dioxygenases (4-8 shRNAs/gene) and then grown under cytokine-poor conditions for 10 days. Shown are mean values of triplicate experiments. (B-C) Proliferation under cytokine-poor conditions (B) and differentiation after 8 days of EPO (C) of TF-1 cells expressing a non-targeting shRNA (shControl) or shRNAs targeting TET2 or TET1, as indicated. (D) Proliferation under cytokine-poor conditions of TF-1 cells expressing a TET2 shRNA after pretreatment for 6 days with DMSO, 250 μM TFMB-(R)-2-HG or TFMB-(S)-2-HG. (E) Immunoblot of TF-1 cells stably expressing the indicated IDH1 variants; untreated (-), treated with vehicle (V) or treated with 100 μM to 1 mM DMOG, as indicated by the triangles, for 3 hours prior to cell lysis. (F-G) Proliferation under cytokine-poor conditions (F) and differentiation after 8 days of EPO (G) of TF-1 cells expressing either IDH1 R132H or an shRNA targeting TET2, and either a non-targeting shRNA (shControl) or shRNAs targeting EglN1. Growth curves show mean values of duplicate experiments ± SD. FACS plots shown are representative results of three independent experiments.

We confirmed that TET2 knockdown, but not TET1 knockdown, recapitulated the ability of IDH1 R132H and (R)-2-HG to promote cytokine-independence and block differentiation of TF-1 cells, suggesting that TET2 inhibition contributes to transformation by mutant IDH (Fig. 3B-3C and fig. S8). This, however, created a paradox, because (S)-2-HG is a more potent inhibitor of TET2 than is (R)-2-HG (6, 8), and yet TFMB-(R)-2-HG, but not TFMB-(S)-2-HG, promoted TF-1 cell transformation (Fig. 2). Moreover, TFMB-(S)-2-HG, but not TFMB-(R)-2-HG, antagonized transformation induced by TET2 knockdown (Fig. 3D). We reasoned that this conundrum might relate to the fact that (R)-2-HG and (S)-2-HG have opposing effects on EglN activity, with (S)-2-HG serving as an inhibitor and (R)-2-HG, at least in some cellular contexts, serving as an agonist (8). Moreover, we found that TF-1 cells expressing IDH1 R132H were relatively resistant to upregulation of HIF1α by the 2-OG competitive antagonist dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG), suggesting that (R)-2-HG acts as an EglN agonist in these cells as well (Fig. 3E). We therefore considered the possibility that inhibition of EglN1 by (S)-2-HG prevents it from transforming TF-1 cells. Indeed, we found that knockdown of EglN1 with multiple independent shRNAs abrogated the growth factor-independence, and restored the differentiation, of TF-1 cells transformed by expression of IDH1 R132H or by knockdown of TET2 (Fig. 3F-3G and fig. S9-S10).

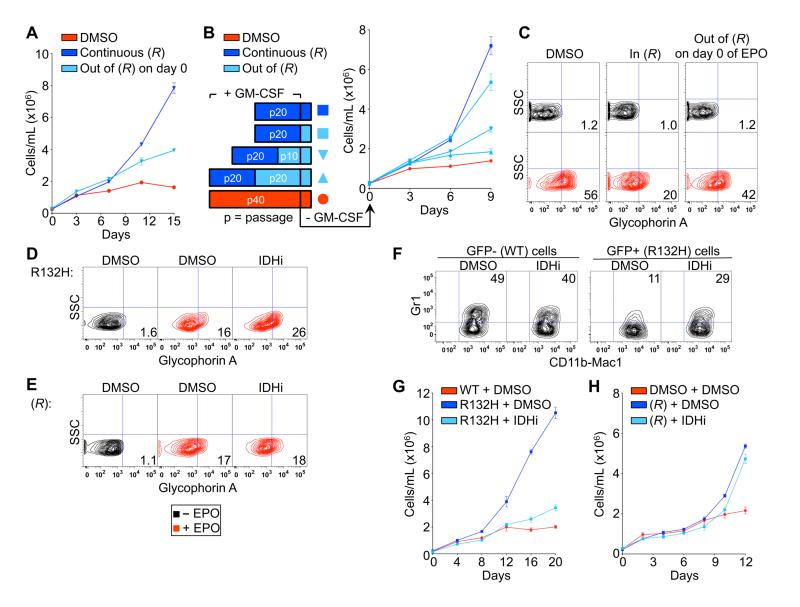

To ask whether the oncogenic effects of (R)-2-HG are reversible, we first confirmed that a minimum of 4 passages in TFMB-(R)-2-HG were required to render TF-1 cells cytokine-independent, provided TFMB-(R)-2-HG exposure was maintained during the cytokine withdrawal period (Fig. 4A). Next, late passage TFMB-(R)-2-HG-treated TF-1 cells were passaged out of TFMB-(R)-2-HG for variable periods prior to removal of GM-CSF (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the amount of time required for reversion of growth factor independence was influenced by the intensity (duration × dose) of TFMB-(R)-2-HG exposure (Fig. 4A-4B). In stark contrast, removal of TFMB-(R)-2-HG rapidly restored the ability of TF-1 cells to differentiate in response to EPO even after long-term passage in the presence of TFMB-(R)-2-HG (Fig. 4C). Of note, late-passage TF-1 cells that expressed lower levels of mutant IDH1 (fig. S3B) and produced lower levels of (R)-2-HG (fig. S7) spontaneously regained the ability to differentiate in response to EPO but remained growth factor-independent (fig. S11).

Fig. 4.

Transformation by (R)-2-HG is reversible. (A) Proliferation of TF-1 cells under cytokine-poor conditions after being passaged 4 times in the presence of DMSO or 250 μM TFMB-(R)-2-HG. At the time of GM-CSF withdrawal TFMB-(R)-2-HG was either maintained [continuous (R)] or removed [out of (R) on day 0]. (B) Proliferation of TF-1 cells under cytokine-poor conditions after being passaged 20 times in the presence of DMSO or 250 μM TFMB-(R)-2-HG and then undergoing wash-out of TFMB-(R)-2-HG for the periods indicated. (C) Differentiation of TF-1 cells after being passaged 20 times in the presence of 500 μM TFMB-(R)-2-HG or DMSO. At the time of EPO administration TFMB-(R)-2-HG was either maintained [in (R)] or removed [out of (R) on day 0]. (D-F) Differentiation of TF-1 cells (D and E) and SCF ER-Hoxb8 cells (F) transformed with IDH1 R132H (D and F) or TFMB-(R)-2-HG (E) and then passaged 5 times in the presence of DMSO or a small molecule inhibitor of IDH1 R132H (1 μM). (G and H) Proliferation under cytokine-poor conditions of early-passage (p15) TF-1 cells transformed with IDH1 R132H (G) or TFMB-(R)-2-HG (H) and then passaged 5 times in the presence of DMSO or a small molecule inhibitor of IDH1 R132H (1 μM) prior to growth factor withdrawal. Growth curves show mean values of duplicate experiments ± SD. FACS plots shown are representative results of three independent experiments.

In a complementary set of experiments, we found that a tool compound (AGX-891) that specifically blocks 2-HG production by IDH1 R132H (fig. S12) (16) restored the ability of IDH1 R132H-expressing TF-1 cells (Fig. 4D) and SCF ER-Hoxb8 cells (Fig. 4F) to differentiate in vitro and abrogated the growth factor independence of IDH1 R132H-expressing TF-1 cells (Fig. 4G and fig. S13). These effects were on-target because they were not observed in cells transformed with TFMB-(R)-2-HG rather than IDH1 R132H (Fig. 4E and 4H).

Tumor-associated IDH mutations cause many metabolic abnormalities in addition to the accumulation of (R)-2-HG (9). Our studies indicate, however, that (R)-2-HG is sufficient to confer the two hallmarks of leukemia, enhanced proliferation and impaired differentiation. (R)-2-HG can inhibit many 2-OG-dependent enzymes, including various histone demethylases and the 5′-methylcytosine hydroxylase TET2 (6-8). We found that downregulation of TET2, like (R)-2-HG, promotes cytokine-independence and blocks differentiation. This is consistent with the model that leukemic transformation by mutant IDH is linked to inhibition of TET2 by (R)-2-HG, thus accounting for the observation that IDH and TET2 mutations both occur in acute leukemia but are mutually exclusive (15).

At intermediate (R)-2-HG concentrations TF-1 cells remain cytokine-independent but can once again differentiate. This observation, together with the behavior of TF-1 cells treated with different doses of (R)-2-HG and their responses to (R)-2-HG withdrawal, strongly suggest that higher levels of (R)-2-HG are needed to block differentiation than to confer cytokine-independence. This suggests that the differentiation phenotype requires more profound TET2 inhibition than the growth phenotype. Interestingly, targeted expression of IDH1 R132H in the murine hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) compartment causes gradual expansion of long-term HSCs without any evidence of impaired myeloid differentiation (17). In contrast, mice lacking TET2 exhibit both expansion of their HSC compartment and aberrant myeloid differentiation (18).

Although TET2 appears to be an important target of (R)-2-HG in our system we have not yet formally proven that TET2 inhibition is necessary, in addition to being sufficient, for transformation by mutant IDH. Inhibition of other 2OG-dependent enzymes by (R)-2-HG may enhance or suppress leukemic transformation by mutant IDH. With respect to the latter, the observation that the levels of mutant IDH and (R)-2-HG fell over time in TF-1 cells grown under growth factor-rich conditions suggests that high levels of (R)-2-HG may be deleterious in certain cellular contexts, perhaps due to inhibition of other 2-OG-dependent enzymes that promote cell growth and survival. These considerations might be relevant to the clinical differences between IDH mutant and TET2 mutant myeloid disorders (19).

Leukemic transformation by 2-HG is specific to the (R) enantiomer produced by mutant IDH and not the (S) enantiomer, even though (S)-2-HG is a more potent inhibitor of all of the 2-OG-dependent enzymes tested to date, including TET2 (6-8). This conundrum appears to be explained by the differential effects of the two enantiomers on EglN1, with (R)-2-HG serving as an agonist and (S)-2-HG as an antagonist (8), and by our observation that loss of EglN1 activity blocks transformation by mutant IDH or loss of TET2. Several studies have suggested that the canonical EglN1 target, HIF, can inhibit hematopoietic stem cell and leukemic cell proliferation (20-26). Interestingly, people living at high altitude, and hence presumed to have lower basal EglN1 activity due to chronic hypoxia, appear to have a lower risk of leukemia (27, 28).

The hypothesis that mutant IDH transforms cells by affecting epigenetic marks has raised fears that these changes will not be reversible in a therapeutically relevant timescale. Our studies suggest that the effects of (R)-2-HG are reversible, offering hope that compounds that block (R)-2-HG production by IDH mutants will benefit patients. Moreover, the relatively rapid reversion of the (R)-2-HG transformation phenotypes suggests that the relevant epigenetic marks are more dynamic than previously suspected or that these phenotypes reflect non-canonical functions of enzymes such as TET2. In addition, our findings suggest that pharmacological inhibition of EglN1 might also be useful for the treatment of leukemias that harbor IDH or TET2 mutations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Katharine Yen, Michael Su and Agios Pharmaceuticals for the IDH1 inhibitor and for sharing unpublished data; Rafael Bejar and Ann Mullally for their valuable input; Andrew Lane and David Sykes for assistance with the SCF ER-Hoxb8 cells; Mahnaz Paktinat and Ronald Mathieu for assistance with flow cytometry; and members of the Kaelin and Ebert lab for technical help and valuable discussion. W.G.K. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Investigator. Supported by the National Istitutes of Health (W.G.K., J.A.L) and HHMI (W.G.K.).

References and Notes

- 1.Falini B, et al. Blood. 2007;109:874. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-012252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mardis ER, et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1058. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaelin WG., Jr Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2011;76:335. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.010975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dang L, et al. Nature. 2009;462:739. doi: 10.1038/nature08617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward PS, et al. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:225. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu W, et al. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:17. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chowdhury R, et al. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:463. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koivunen P, et al. Nature. 2012;483:484. doi: 10.1038/nature10898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reitman ZJ, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:3270. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitamura T, et al. J. Cell. Physiol. 1989;140:323. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041400219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang GG, et al. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:287. doi: 10.1038/nmeth865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gross S, et al. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:339. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi C, et al. Nat. Med. 2012;18:624. doi: 10.1038/nm.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delhommeau F, et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2289. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figueroa ME, et al. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:553. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popovici-Muller J, et al. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:850. doi: 10.1021/ml300225h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sasaki M, et al. Nature. 2012;488:656. doi: 10.1038/nature11323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moran-Crusio K, et al. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdel-Wahab O, Patel J, Levine RL. Hem. Onco. Clin. North Am. 2011;25:1119. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song LP, et al. Oncogene. 2008;27:519. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu W, et al. Blood. 2006;107:698. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen PO, et al. Cell Prolif. 2000;33:381. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2184.2000.00183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chow DC, et al. Biophy. J. 2001;81:675. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75732-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forristal CE, et al. Blood. 2012 Dec 14; Epub. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takubo K, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:391. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salomon-Nguyen F, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:6757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120162297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eckhoff ND, et al. Health Physics. 1974;27:377. doi: 10.1097/00004032-197410000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinberg CR, Brown KG, Hoel DG. Radiation Research. 1987;112:381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weber K, et al. Mol. Therapy. 2008;16:698. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo B, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:20380. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashton JM, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:359. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.